行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫

□成

果 報 告

■期中進度報告

綠色新產品開發成功的前因與結果模式之建構與實證研究─

以台灣地區電機電子產業為例

The models building and empirical research about the antecedents and

consequences of green new product development success-

The case of Electric and Electronic Industries in Taiwan

計畫類別:■ 個別型計畫 □ 整合型計畫

計畫編號:

98-2410-H-151-004-MY2

執行期間:

2009 年 8 月 1 日至 2011 年 7 月 31 日

主 持 人:黃義俊 國立高雄應用科技大學企業管理系 副教授

計畫參與人員:邱妙惠 國立高雄應用科技大學企業管理系 助教

:張雋庭 國立高雄應用科技大學企管系碩士生

:王湘捷 國立高雄應用科技大學企管系碩士生

成果報告類型(依經費核定清單規定繳交):■精簡報告 □完整報告

本成果報告包括以下應繳交之附件:

□赴國外出差或研習心得報告一份

□赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告一份

■出席國際學術會議心得報告及發表之論文各一份

□國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告書一份

處理方式:除產學合作研究計畫、提升產業技術及人才培育研究計畫、

列管計畫及下列情形者外,得立即公開查詢

□涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,□一年■二年後可公開查詢

執行單位:國立高雄應用科技大學企管系

中 華 民 國 九十九 年 五 月 二十一 日

摘要: 引進社會網絡的研究,本研究提出家族企業的內部社會網絡影響家族企業的能力在涉入 和學習對於綠色新產品開發的開發過程中。本研究的主要目的是探討家族企業對於綠色新產 品開發的調節效果。從181份台灣製造業的有效樣本中,結果建議管理的行動可以改善綠色 新產品開發的績效,而且家族與非家族企業會造成不同的影響。 關鍵詞:綠色新產品開發、內部社會網絡、環保績效、財務績效、家族企業。 Abstract:

Drawing on the social network research, we propose that the internal social networks of family firms have profound impact on a family firm’s ability to involve and to learn from non-conventional stakeholder in the process of green new product development. The primary objective of our research is to examine the moderation effect of family firms in select green new product development practices. We tested our hypotheses using by surveying 181 manufacturers from Taiwan. Our analytical results suggest that managerial actions to improve green product development are likely to generate different impacts in family and non-family firms.

Keywords: Green new product development, internal social networks, environmental performance,

financial performance, family firms.

This paper has been accepted by

2010 Academy of Management Annual Meeting Montréal, Canada - August 6-10

INTRODUCTION

The emergence of natural environmental challenges in the last quarter of the twentieth century has motivated multinational efforts to manage these natural environmental problems. International treaties such as The Montreal Protocol on Substances That Deplete the Ozone Layer (1987) and The Basel Convention (1989) are notable milestones of such natural environmental management efforts. As national governments are more engaged in natural environmental issues, trade sanction and other regulatory measures are being developed to impose natural environmental responsibilities on companies. In addition, the general public’s awareness of natural environmental challenges motivates customers and the governments to advocate for the development of more environmentally responsible green new products. As commercial success of green new products is increasingly crucial in moving companies and society towards environmental sustainability, the development of green new products has demonstrated as a new source of long-term competitive advantage of firms.

The development of green product innovations is not necessarily associated with technological breakthroughs, however such project is most likely to be associated with the involvement of stakeholders who are seldom participants of conventional new product development (NPD) projects. For example, environmental activities may play a key role in green NPD but not in conventional NPD. Such organizational capability to identify and to integrate stakeholder opinions is an important organizational capability (Sharma & Vredenburg, 1998) in the development of environmental friendly products.

Among the companies developing green new products, family firms are a group of particular significance for two reasons. First, family controlled firms account for some 70 percent of GDP and employment in the global economy (Neubauer & Lank, 1998: 10). In addition, family firms are more likely to engage in environmentally friendly practices than their non-family counterparts (Craig & Dibrell, 2006). Second, a family firm is a business organization owned and controlled by a family. The boards and top management team are either filled with family member s or many long-time family friends. This practice increases the closeness of social networks in the family firms. As closely-knit social networks breed trust and mutual understanding among its members, such a social network improves the effectiveness of minor problem solving and developing incremental product innovations (Gulati, 1995). However, a close social network for innovation, or innovation network, is also likely to hinder the acquisition and transfer of radically new ideas for the development of discontinuous or radical innovation projects (Granovetter, 1973; Uzzi, 1996).

Drawing on the social network research, this research proposes that the internal social networks of family firms have profound impact on a family firm’s ability to involve and to learn from non-conventional stakeholder in the process of green new product development. We tested our hypotheses using by surveying 181 manufacturers from Taiwan. This project will underscore the interactions between stakeholder integration and innovation network. The findings will

contribute to the literature of green NPD and NPD in general. Additionally, our examination of innovation network in family business is likely to enhance our understanding in what drives family firms behaving differently from non-family firms. Finally, for managers and policy makers, the outcomes of this project may shed lights to developing new managerial tools to assist family firms improve the effectiveness in green new product innovations. This paper is organized as follows. Next section reviews the literature of NPD, social network in family firms, followed by a review of green new product development research and hypothesis development. The methodology section introduces the research design, implementation, and the results of statistical analysis. Major research implications and managerial implications are presented in the discussion section.

INNOVATION NETWORK AND NPD

An effective NPD process is an organizational learning process in which developers create, transfer, and utilize knowledge for product development activities (Iansiti, 1997; Kale & Singh, 2007; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Kumar & Nti, 1998; Tsai, Ding, & Rice, 2008; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Wheelwright & Clark, 1992). An effective innovation developer must be capable of identifying the sources of critical knowledge and to manage, integrate relevant knowledge to the development of new products (Ding & Peters, 2000; Dougherty, 1990; Iansiti, 1997; Kogut, 2000).

However, the organizational capability to identify and to manage relevant innovation knowledge is closely associated with the innovation network of the innovation developer. A close or strong innovation among individuals within a firm breeds trust between them and encourages sharing of valuable knowledge (Krackhardt, 1992). Members of such strong networks usually know each other well. Additionally, because of their long friendship or past interactions, the members of a strong network are able to understand the needs of other members in the network. Based on his observations of New York City-based garment industries, Uzzi (1996) pointed out that over time, a strong social network emerge among garment workers. This network is a common platform for the transfer of knowledge and other resources for innovations (Gulati, 1999; Kogut, 2000). However, weak, or arms-length, relationships are more effective sources for novel ideas because strong social ties, defined by frequent interactions and long-term associations, are likely to share similar perspectives. On the contrary, individuals who have limited interactions are unlikely to share similar perspectives developed from long-term close interactions (Granovetter, 1973; Mizruchi & Fein, 1999).

Both organizational capabilities, efficient problem solving and acquisition of non-conventional ideas, are important sources of sustainable competitive advantage of a firm, as firms need both incremental innovations and radical innovations to keep up with competitions (Hill & Rothaermel, 2003; Rice, O'Connor, Peters, & Morone, 1998). Organizations need to be able to utilize its existing innovation network and, in a lower frequency, reconfigure its innovation network to identify and to manage relevant stakeholders for both incremental and radical innovation projects.

factors contribute to new product success by utilizing existing innovation network, others require reconfiguration of innovation networks. Examples of the former include organizational commitment to the development of a project and R&D activities, cross-function integration represent a common practice to reconfigure existing innovation networks.

GREEN NPD AND INNOVATION NETWORK IN FAMILY FIRMS

The main difference between a green new product and any other new product is that the former has unique product attributes addressing one or more environmental concerns. Examples of these attributes include recyclability, recycled content, fuel efficiency, toxic content reduction, and emission-related performance. Green new product development is a process through which an organization creates a new product or redesigns an existing product to reduce negative impact to the natural environment (Berchicci & Bodewes, 2005; Pujari, Wright, & Peattie, 2003). While compliance to environmental regulations may still be an important factor in a firm’s decision to develop green products, an increasing number of firms have committed to the development of green products to enhance their competitive position in the markets. Empirical evidence has suggested that an organization’s ability to align environmental issues with new product development can improve market performance (Baumann, Boons, & Bragd, 2002). The integration of environmental attributes in new product development process requires developers to re-evaluate the role of existing stakeholders in the product development process (Polonsky, Rosenberger, & Ottman, 1998). Although the development process of a green NPD is very similar to one of conventional NPD, the Green NPD requires innovators to integrate stakeholders, who otherwise would not be included in the NPD process, into the process of product development. For example, new suppliers will have to be identified and contracted to supply key components for the new green products. The developers also have to acquire new market and technology information to support the development of new green products. The main challenge to developers of green new products is to attain both high environmental performance and high financial performance through the successes of new products. In summary, the main difference between green NPD and conventional NPD is that the compositions of stakeholders are very different from each other. Therefore NPD practices emphasizing network reconfiguration may have a more important role in green NPD success than network utilizing practices. This effect may be more salient in organizations with close, strong innovation networks such as family firms.

NETWORK UTILIZATION AND RECONFIGURATION IN FAMILY FIRMS

A widely reported attribute of family firms around the world is the involvement of family members in the decision-making and operations of the firm. Previous studies have documented that appointing family members on the board or managerial positions are common in family firms (Davis & Harveston, 1998; Mariussen, Wheelock & Baines, 1998; Ram & Holliday, 1993; Simpson, Wilson, & Jackson, 1992). The family ties constitute the core of internal social network

in a family firm. The family members are close to each other as they generally have long history of interaction even before becoming co-workers or co-founders. Family members are also likely to have frequent interactions among themselves. These strong and close relationships among family members form the foundation of social capital within family firms (Arregle, Hitt, Sirmon, & Very, 2007).

The construction of this strong social network within the organization enables family owners to transfer the common family values such as loyalty, fairness, and harmony to their family firms (Ram & Holliday; 1993). This network can also reinforce the behavioral preference such as risk-aversion and long-term orientation. Since individuals bonded by close social ties develop strong trust toward each other, family members are willing to fund the family firm or to contribute disproportionately more in marginal productivity relative to compensation in order to sustain the growth of the family firms (Mariussen, Wheelock, & Baines, 1998; Simpson, Wilson, & Jackson, 1992). Strong ties among family members also enhance family cohesiveness (Salvato & Melin, 2008). As a family firm grows, non-family staff, manager, and board members are recruited to fill the newly created positions. The internal social network connecting the family members would expand to connect select non-family employees or directors. The internal network provides a mechanism of socialization (Portes, 1998) to ensure non-family employees occupying key positions understand and accept the norms and obligations upheld by the family owners.

The strong social network within family firms is likely to have profound impact on the behaviors of family firms. For example, Chirico and Salvato (2008) propose that the social capital derived from the internal social network enhances the knowledge integration among family members. In addition, close relationship among family members increase the willingness of knowledge integration within family. Although there is little evidence about the impact of family-based internal social network in family firms on the development of novel new products, the close internal social network in family firms are likely to affect outcome of non-conventional NPD.

Extensive research has offered guidelines, manuals, and tools to assist engineers and managers to effectively integrate environmental concerns into the new product development process (Brezet & Hemel, 1997; Mackenzie, 1997). While some of these practices have little impact on the composition of stakeholders in the NPD process, network reconfiguring practices such as cross function integration enable firms to integrate environmental stakeholders to the NPD process more effectively. Given the strong-tie nature of innovation networks in family firms, network utilization and network reconfiguration practices are likely to have different effects in green NPD performances in family and in non-family firms.

Environmental Commitment and R&D

Corporate environmental policy refers to an organization’s commitment to green NPD. Such commitment is reflected in the support from the top management and explicit expressions of environmentally responsible policies. Management supports and policy expressions provide a

platform to incorporate an explicit and clearly defined environmental product strategy into the overall corporate strategy. An explicit product innovation strategy enables managers to plan for specific product development (Gupta & Wilemon, 1990). In addition, the outcome of the new product development process depends upon the willingness of top management to commit R&D activities and other resources to the new projects (Dwyer, 1990; Hegarty & Hoffman, 1990).

However, the development of green new products requires developers to review the existing product development process and even design green substitute products to replace their existing product lines. Development teams need to search for new information and to involve individuals (e.g. environmental lawyers or community groups) who are not included in conventional product development process in the new product process. Firms capable of reaching out to acquire such new information and involve new participants are more likely to develop successful green new products than the other firms. The intrafirm network plays a vital role in the process because this social capital assists in-house developers to identify internal and external information sources and participants for green product development projects. As the internal network in family firms are closer or stronger than that of non-family firms’ (Tsui-Auch, 2005), we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 1a. Family and non-family firms will moderate the relationship between the organizational commitment to environmental responsibility and the environmental performance of green innovation projects, such that the relationship is lower in family firms than in non-family firms.

Hypothesis 1b. Family and non-family firms will moderate the relationship between the organizational commitment to environmental responsibility and the financial performance of green innovation projects, such that the relationship is lower in family firms than in non-family firms.

Hypothesis 2a. Family and non-family firms will moderate the relationship between the R&D strength and the environmental performance of green innovation projects, such that the relationship is lower in family firms than in non-family firms.

Hypothesis 2b. Family and non-family firms will moderate the relationship between the R&D strength and the financial performance of green innovation projects, such that the relationship is lower in family firms than in non-family firms.

Cross-Functional Integration

Product development is a complex social process involving people from different backgrounds and management positions (Dougherty, 1992). To a large extent, the success of a product depends

on the effective communication and collaboration between the various members of the team (Cooper & Kleinschmidt, 1993; Dougherty, 1992). Cross-functional integration has been identified as a key driver of new product success (Griffin & Hauser, 1996; Gupta, Raj, & Wilemon, 1986; Olson, Walker, & Reuker, 1995). Cross-functional integration typically involves facilitating communication among different functions (Gatingnon & Xuereb, 1997; Song, Montoya-Weiss, & Schmidt, 1997; Troy, Hirunyawipada, & Paswan, 2008). When environmental issues are integrated into the various functional areas of a firm, the environmental issues are more likely to be integrated into the strategic planning process (Judge & Dogulas, 1998). Developing the capability to incorporate environmental issues into the strategic planning process allows environmental champions to assert themselves in the green product development process (Fineman & Clarke, 1996; Winn, 1995). In summary, organizational commitment to cross-functional integration enable a firm to engage multiple stakeholders and diverse source of information for new product development.

Cross-functional integration complements the existing social capital of an organization by bringing new expertise or information to the process of green new product development. As family firms are more likely to have an effective new product development platform derives from its close internal network, we hypothesize that family firms positively moderate the relationship between cross-function integration and green new product performances.

Hypothesis 3a. Family and non-family firms will moderate the relationship between the cross-functional integration and the environmental performance of green innovation projects, such that the relationship is higher in family firms than in non-family firms.

Hypothesis 3b. Family and non-family firms will moderate the relationship between the cross-functional integration and the financial performance of green innovation projects, such that the relationship is higher in family firms than in non-family firms.

The hypothesized relationships are illustrated in the research model (Fig.1).

*** Insert Figure 1 about here***

METHODOLOGY

We adopted existing survey items to measure our dependent variables and independent variables. However, since these survey items are developed for American managers, we translated the questions and invited a panel of seven highly experienced professionals to review the validity of the translated questions. The refined questions were pretested in environmental managers from thirty six companies listed in the directory of Taiwan Electrical and Electronic Manufacturer’s Association. The feedbacks help us further refine the questionnaire. Our two dependent variables and two independent variables are measured using seven-point Likert scale from 1 to 7 rating from

strongly disagreement to strongly agreement.

Measure Development

The measurement of environmental performance included four items: (1) The company chooses the materials of the product that produce the least amount of pollution for conducting the product development or design; (2) the company chooses the materials of the product that consume the least amount of energy and resources for conducting the product development or design; (3) the company uses the fewest amount of materials to comprise the product for conducting the product development or design; (4) the company would circumspectly deliberate, whether the product is easy to recycle, reuse, and decompose for conducting the product development or design (Chen, Lai, & Wen, 2006). The financial performance was measured using a four-item scale. The items were developed from prior research in natural environmental issues (Judge & Douglas, 1998). Measuring perceived financial performance has been used successfully in the literature (Covin, Slevin, & Schulz, 1994; Dess, 1987; Miller & Friesen, 1994).

We measured corporate environmental policy as the respondent’s perception of environmental policy and top managerial support for green new product development. The environmental policy was measured with four items developed by Pujari, Wright and Peattie (2003). The

cross-functional integration was measured using an eight-item scale. The items were modified

from prior research in new product development (Gupta, Rja, & Wilemon, 1986; Moenaert & Souder, 1990). We focus on the extent of behavioral activities of marketing-R&D-environmental communication and cooperation for green new product development project.

Following Lee and Ma (2006), a family firm is defined as a company where (1) the members of the controlling family (i.e., the family group having the largest control rights) jointly hold at least 10% of equity ownership of the company, and they also hold at least one board seat at the company, or (2) the members of a family or the legal representatives from other companies/entities controlled by the family jointly hold more than 50% of board seats. Among 181 valid responses, eighty companies are identified as family firms.

We have also included four control variables in this study, age, size, environmental benchmarking, and R&D strength. The age is calculated as the difference between 2008 and the founding year of organization. As an organization grows older, organizational efforts to adopt new innovation may be hindered by organizational inertia (Egri & Herman, 2000). We control the size of firms because large organizations are more likely to have resources to adopt new innovations (De Luca & Atuahene-Gima, 2007) and to take an active role in natural environmental management (Aragon-Correa, 1998). Following Child (1972), the size of firm is the log value of number of employees.

Benchmarking is a firm seeks to identify best practices that produce superior results in other firms and to replicate these to enhance the competitive advantage of the observing organizations (Camp, 1995; Mittelstaedt, 1992; Vorhies & Morgan, 2005). Environmental benchmarking was found to affect the performance of green innovations in the market (Pujari et al., 2003). Following

Pujari, Wright and Peattie (2003), we measure this variable using seven Likert scale items. Finally, we controlled the R&D Strength of a firm because an organization’s resources and capabilities to develop new innovation would have profound impact on the performance of innovations (Li & Calantone, 1998). We adopted the three items used in Li and Calantone (1998). The first was the R&D expenditure in dollars relative to sales. The next two items asked the respondent to assess the strength of the company’s R&D investment and proprietary technology relative to its largest competitor’s.

Sample and Data Collection

To test our hypotheses, we randomly selected one thousand member firms of Taiwan Electrical and Electronic manufacturer’s Association (TEEMA). In 2008, this organization has nearly four thousand members who contribute about 50% of GDP of Taiwan. One thousand questionnaires were mailed to the selected companies in late 2008. We asked for the managers responsible for environmental management to respond to our questionnaires. As the designated individual responsible for this task have different job title in different organizations, our respondents include CEOs, Environmental Protection Managers, Marketing Manager, and R&D Manager. Our responded are asked to complete and to return the questionnaires in two weeks.

Historically, manufacturers from these two industries are major sources of industrial waste and pollutions. Additionally, unlike high pollution industries in more developed economies, the Taiwanese government and manufacturers are still in the process of correcting the natural environmental damages from strong for-growth policies not too long ago. A second reason to conduct our research in Taiwan, Taiwanese economy is known for its high concentration of family-owned manufacturers which increases the likelihood of obtaining sufficient number of family firm responses from our sample pool.

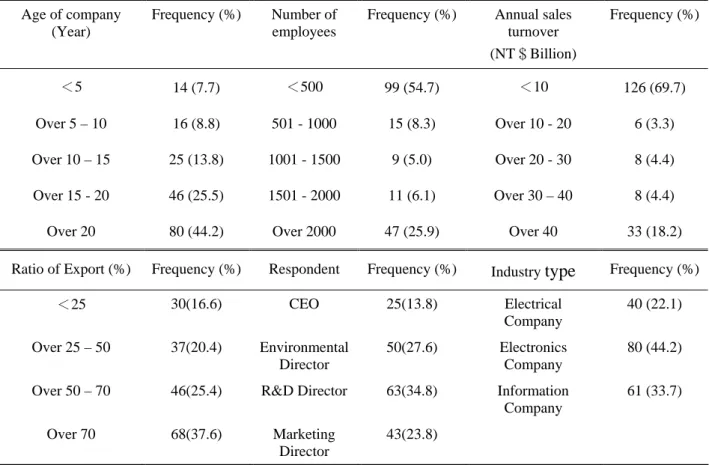

We received 188 responses. Seven responses were eliminated because they are not complete. The final number of valid responses is 181 (Table 1). The 18.1% respond rate is comparable to other survey-based strategy research (Delmas & Toffel, 2008; Hoskisson, Cannella, & Tihanyi, 2004; McEvily & Chakravarthy, 2002; Slater & Olson, 2001).

*** Insert Table 1 about here***

We examined the differences between respondents and non-respondents using the size of firm, number of employees, and industry. No significant differences were found. Further, t tests were applied between a sample of early responses and very late responses. The results did not provide significant differences either. The factor analysis was performed examine common method bias.

Data Analysis

scales. To test the hypothesized relationship, the moderated regression analysis is performed to examine the moderating effect of family firms in the relationships between corporate policy, cross-functional integration and performance. Table 2 and 3 shows the factor analysis results. The results show two factors with eigenvalues greater than one, accounting for 78.392% of the variance (K-M-O statistic 0.926; Barlett statistic 2806.729, significance 0.000). An analysis of Screen plot also shows a two-factor solution. The reliability of these factors is measured using Cronbach’s alpha, the result shows all over 0.7 (Churchill, 1979).

*** Insert Table 2, 3 about here*** Descriptive Statistics

Before we tested the hypotheses, we examined a correlation matrix for the composite scales of the major constructs (see Table 4). The signs of the bivariate correlation appear to be consistent with the hypothesized relationships. There is also variability in the measures of the major constructs, as reflected by the means and standard deviations shown in Table 4.

***Insert Table 4 Here***

We used moderated regression analysis to test our hypotheses. Following Aiken and West (1991) and Jaccard and Turrisi (2003), we centered (-x = 0) the independent’ variables when performing our moderated regression analysis to minimize the effects of any multicollinearity among variables comprising our interaction terms. Table 5 and 6 summarize our results.

According to Table 5 Model C, the family business dummy variable negatively significantly moderates the relationship between corporate environmental policy and environmental performance and the relationship between R&D strength and environmental performance while positively significantly moderates the relationship between cross-functional integration and environmental performance, supporting hypotheses 1a, 2a, and 3a.

*** Insert Table 5 about here***

According to Table 6 Model F also tests our family business hypothesis. The family business dummy variable negatively moderates the relationship between corporate environmental policy and financial performance and between R&D strength and financial performance. This moderation effect is significant at the level of < 0.05, supporting H1b and H2b. On the other hand, family business positively moderates the relationship between cross-functional integration and financial performance, supporting H3b.

*** Insert Table 6 about here***

Our analysis shows that environmental benchmarking is significant predictors to the performance of green new product development. In addition, corporate policy and cross-function integration, independent variables of this research, also positively correlate to the commercial and environmental success of green new product development. These results are consistent with the previous studies on the antecedents of successful green new product development (Pujari et al., 2003).

The regression analysis also confirms the hypothesized moderation effect between independent variables, corporate policy, R&D strength, and cross-function integration, and dependent variable, performances. This result suggests that the close innovation network in family firms moderate the impacts of corporate policy and cross-functional coordination on the outcome of green new product development. The close innovation network provides an effective problem solving platform for new product development when family firms develop conventional new products.

Our findings have two research implications. First, many researchers have examined and identified factors contributing to the adoption of green new product development (Johansson, 2002), such as the integration of environmental professionals (Ehrenfeld & Lenox, 1997), and top management support (Ehrenfeld & Lenox, 1997; Pujari et al., 2003) are considered crucial factors. These conclusions may have to be modified if we specifically look for the moderation effect of family firms in these relationships.

Second, since the innovation network in family firms moderate the effects of organizational actions, family firms may be adopt different approaches than their non-family counterparts to address strategic and organizational challenges. Family business literature has documented a great number of behavioral differences between family and non-family firms. While some of the differences may be attributed to the family values and regional culture, as proposed in a recent study by Salvato and Melin (2008), the close innovation network within the a family firm may be a key predictor of behavioral uniqueness of family firms.

The managerial implication of our research is that managers of family firms can improve their abilities to acquire new technology and market information by constructing a more balanced innovation network for innovation. Managers in family firms may develop and implement organizational mechanisms such as cross-functional coordinator to improve their organizations’ ability to acquire and process novel information.

Limitation and Future Research Directions

This study verified hypotheses with a questionnaire survey, only providing cross-sectional data. A longitudinal research design is necessary to validate these claims of causality. Furthermore, because respondents provided data on both the independent and the dependent variables, there is the possibility that the correlations are inflated as a result of single-source bias. The results of Harman’s one-factor test (Podsakoff & Organ 1986) enabled us to rule out single-source bias. However, the fact remains that data collected from multiple sources (e.g., senior management,

organizational employees) would have provided a stronger test of the model. This study is focused on the information and electronics industry in Taiwan, an emerging economy with strong Confucius transition. Our findings may be more applicable to similar economies such as Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia than in more developed economies such as Canada and the United States. Further research on the effects of institutional condition in economies of different developmental stages and regional cultural tradition in our findings may clarify the role of intrafirm network within family firms in the development of green new products.

REFERENCES

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and. interpreting interactions, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Aragon-Correa, J. A. 1998. Strategic proactivity and firm approach to the natural environment.

Academy of Management Journal, 41(5): 556-567.

Arregle, L., Hitt, M., Sirmon, D., & Very, P. 2007. The development of organizational social capital: Attributes of family firms. Journal of Management Studies, 44(1): 73-95.

Baumann, H., Boons, F., & Bragd, A. 2002. Mapping the green product development field: engineering, policy and business perspectives. Journal of Cleaner Production, 10: 409-425. Berchicci, L., & Bodewes, W. 2005. Bridging environmental issues with new product

development. Business Strategy and Environment, 14: 272-285.

Brezet, H., & van Hemel., C. 1997. Ecodesign– A promising approach to Sustainable production

and consumption. UNEP.

Camp, R. C. 1995. Business process benchmarking: Finding and implementing best practices. Milwaukee, WI: ASQC Quality Press.

Chen, Y. S., Lai, S. B., & Wen, C. T. 2006. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(4): 331-339.

Child, J. 1972. Organization structure, environment and performance: The role of strategic choice.

Sociology, 6: 1-22.

Chirico, F., & Salvato, C. 2008. Knowledge integration and dynamic organizational adaptation in family firms. Family Business Review, 21(2): 169-181.

Churchill, G. A. Jr. 1979. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing construct.

Journal of Marketing, 16 (February): 64-73.

Cooper, R. G., & Kleinschmidt, E. J., 1993. Stage gate systems for new product success.

Marketing Management, 1 (4): 20–29.

Covin, J., Slevin, D., & Schulz, R. 1994. Implementing strategic missions: Effective strategic, structural and tactical choices. Academy of Management Journal, 31: 418-505.

Craig, J. & Dibrell, C. 2006. The natural environment, innovation, and firm performance: A comparative study. Family Business Review, 19(4): 275–288.

Davis, P. S., & Harveston, P. D. 1998. The influence of family on the family business succession process: A multi-generational perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(3): 31-53.

De Luca, L. M., & Atuahene-Gima, K. 2007. Market knowledge dimensions and cross-functional collaboration: Examining the different routes to product innovation performance. Journal of

Marketing, 71 (January): 95-112.

Opening the black box. Strategic Management Journal, 29: 1027–1055.

Dess, G. 1987. Consensus on strategy formulation and organizational performance. Strategic

Management Journal, 8: 259–277.

Ding, H. B., & Peters, L. S. 2000. Inter-firm knowledge management practices for technology and new product development in discontinuous innovation. International Journal of

Technology Management, 20(5-8): 588-600.

Dougherty, D. 1990. Understanding new markets for new products. Strategic Management

Journal, 11: 59-78.

Dougherty, D. 1992. Interpretive barriers to successful product innovation in large firms.

Organization Science, 3(2): 179-202.

Dwyer, L. M. 1990. Factors affecting the proficient management of product innovation.

International Journal of Technology Management, 5(6): 721-730.

Egri, C. P., & Herman, S. 2000. Leadership in the North American Environmental Sector: Values, leadership styles, and contexts of environmental leaders and their organizations. Academy of

Management Journal, 43(4): 571-604.

Ehrenfeld, J., & Lenox, M. J. 1997. The Development and implementation of DFE program.

Journal of Sustainable Product Design, April: 17-27.

Fineman, S, & Clarke, K. 1996. Green stakeholders: Industry interpretations and response.

Journal of Management Studies, 33(6): 715-730.

Gatingnon, H., & Xuereb, J. M. 1997. Strategic orientation of the firm and new product performance. Journal of Marketing Research, 34: 77-90.

Granovetter, M. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6): 1360-1380.

Griffin, A., & Hauser, J. R. 1996. Integrating R&D and marketing: A review and analysis of the literature. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 13: 191-215.

Gulati, R. 1995. Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractural choice in alliance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1): 85-112.

Gulati, R. 1999. Network location and learning: The influence of network resources and firm capabilities on alliance formation. Strategic Management Journal, 20(5): 397-420.

Gupta, A. K., & Wilemon, D. 1990. Improving R&D/marketing relations: R&D's perspective.

R&D Management, 20(4): 277-290.

Gupta, A. K., Raj, S. P., & Wilemon, D. L. 1986. A model for studying R&D-marketing interface in the product innovation process. Journal of Marketing, 50(12): 7-17.

Hegarty, W. H., & Hoffman, R. C. 1990. Product/market innovations: A study of top management involvement among four cultures. The Journal of Product Innovation Management, 7(3): 186-199.

Hill, C. W. L., & Rothaermel, F. T. 2003. The performance of incumbent firms in the face of radical technological innovation. Academy of Management Review, 28 (2): 257-274.

Hoskisson, R. E., Cannella, A. A. Jr, Tihanyi, L., & Faraci, R. 2004. Asset restructuring and business group affiliation in French civil law countries. Strategic Management Journal, 25(6): 525–539.

Iansiti, M. 1997. Technology integration: Making critical choices in a dynamic world. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Jaccard, J., & Turrisi, R. 2003. Interaction effects in multiple regression. Second Edition, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Johansson, G. 2002. Success factors for integration of ecodesign in product development.

Environmental Management and Health, 13(1): 98-107.

Judge, Jr. W. Q., & Douglas, T. D. 1998. Performance implications of incorporating natural environmental issues into strategic planning process: An empirical assessment. Journal of

Management Studies, 35(2): 241-262.

Kale, P., Singh, H., & Perlmutter, H. 2000. Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: Building relational capital. Strategic Management Journal, 21: 217-237. Kogut, B., & Zander, U. 1992. Knowledge of the firm, combinative capabilities, and the

replication of technology. Organization Science, 3:383-397.

Kogut, B. 2000. The network as knowledge: Generative rules and the emergence of structure.

Strategic Management Journal, 21: 405–425.

Krackhardt, D. 1992. The strength of strong ties: The importance of philos in organizations. in Nohria, N., Eccles, R. (Eds), Networks and organizations: Structure, form, and action. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Kumar, R., & Nti, K. O. 1998. Differential learning and interaction in alliance dynamics: A process and

outcome discrepancy model. Management Sciences, 9(3): 356-368.

Lee, Y. C., & Ma, T. 2006. The study of the cost of debt financing of Taiwan's family firms.

Management Review, 25(3): 69–91.

Li, T., & Calantone, R. J. 1998. The impact of market knowledge competence on new product advantage: Conceptualization and empirical examination. Journal of Marketing, 62: 13-29. Mackenzie, D. 1997. Green design: Design for the environment. London: Laurence King.

Mariussen, A., Wheelock, J., & Baines, S. 1998. The family business tradition in Britain and Norway: Modernization and reinvention. International Journal of Management and

Organization, 27(3): 64-85.

McEvily, S. K., & Chakravarthy, B. 2002. The persistence of knowledge-based advantage: An empirical test for product performance and technological knowledge. Strategic Management

Miller, C. C., & Friesen, P. H. 1994. Strategic planning and firm performance: A synthesis of more than two decades of research. Academy of Management Journal, 37: 1649-1665. Mittelstaedt, R. J. Jr. 1992. Benchmarking: How to learn from best in class practices. National

Productivity Review, 11(3): 301-315.

Mizruchi, M. S., & Fein. L. C. 1999. The social construction of organizational knowledge: A study of the uses of coercive, mimetic, and normative isomorphism. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 44(4): 653-683.

Moenaert, R. K., & Souder, W. E. 1990. An information transfer model for integrating marketing and R&D personnel in new product development projects. Journal of Product Innovation

Management, 7: 97-107.

Mariussen, A., Wheelock, J., & Baines, S. 1998. The family business tradition in Britain and Norway: Modernization and reinvention? International Journal of Management and

Organization, 27(3): 64-85.

Neubauer F., & Lank, A. G. 1998. The family business: Its governance for sustainability. New York: Routledge.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. 1995. The knowledge-creating company. New York: Oxford University Press.

Olson, E. M., Walker Jr., O. C., & Reuker, R. W. 1995. Organizing for effect new product development: The moderating role of new product innovativeness. Journal of Marketing, 59: 31-45.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. 1986. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4): 531-544.

Polonsky, M., Rosenberger, P., & Ottman, A. 1998. Developing green products: Learning from stakeholder. Journal of Sustainable Development, 1(5): 7-21.

Portes, A. 1998. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual review of

Sociology, 24: 1-24.

Pujari, D., Wright, G., & Peattie, K. 2003. Green and competitive: Influences on environmental new product development performance. Journal of Business Research, 56(8): 657-671. Ram, M., & Holliday, R. 1993. Relative merits: Family culture and kinship in small firms.

Sociology, 27(4): 629-648.

Rice, M., G. C., O'Connor, Peters, L. S., & Morone, J. 1998. Managing discontinuous innovation.

Research Technology Management, 41(3): 52-58.

Salvato, C., & Melin, L. 2008. Creating value across generations in family-controlled businesses: The role of family social capital. Family Business Review, 21(3): 259-276.

Sharma, S., & Vredenburg, H. 1998. Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively value organizational capability. Strategic Management

Journal, 19: 729-753.

Simpson, I. H., Wilson, J., & Jackson, R. 1992. The contracting effects of social, organizational, and economic variables on farm production. Work and Occupation, 19(3): 237-254.

Slater, S. F., & Olson, E. M. 2001. Marketing’s contribution to the implementation of business strategy: an empirical analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 22(11): 1055–1067.

Song, X. M., & Montoya-Weiss, M. M. 2001. The effect of perceived technological uncertainty on Japanese new product development. Academy of Management Journal, 44: 61-80.

Song, X. M., Montoya-Weiss, M. M., & Schmidt, J. B. 1997. Antecedents and consequences of cross-functional cooperation: A comparison of R&D, manufacturing, and marketing perspectives. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 14: 35-47.

Troy, L. C., Hirunyawipada, T., & Paswan, A. K. 2008. Cross-functional integration and new product success: An empirical investigation of the findings. Journal of Marketing, 72: 132-146.

Tsai, S. L., Ding, H. B., & Rice, M. E. P. 2008. The effectiveness of learning from strategic alliances: A case study of the Taiwanese textile industry. International Journal of

Technology Management, 42(3): 310–328.

Tsui-Auch, L. S. 2005. Unpacking regional ethnicity and the strength of ties in shaping ethnic entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 26(8): 1189-1216.

Ulrich, K., & Eppinger, S. 1995. Product design and development. New York: McGraw-Hill Inc. Uzzi, B. 1996. The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of

organizations: The network effect. American Sociological Review, 61(4): 674-698.

Vorhies, D. W., & Morgan, N. A. 2005. Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing, 69: 80-94.

Westhead, P., & Howorth, C. 2006. Ownership and management issues associated with family firm performance and company objectives. Family Business Review, 19(4): 301-316. Wheelwright, S. C., & Clark, K. B. 1992. Creating project plans to focus product development.

Harvard Business Review, 70(2): 70-82.

Winn, M. 1995. Corporate leadership and policies for the natural environment. In Collins D. and Stark, M. (Eds.), Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, Supplement 1:127-161. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Zahra, S. A., Hayton, J. C., & Salvato, C. 2004. Entrepreneurship in family vs. non-family firms: A resource-based analysis of the effect of organizational culture. Entrepreneurship Theory

TABLE 1 The Profile of Sample

Age of company (Year)

Frequency (%) Number of employees

Frequency (%) Annual sales turnover (NT$Billion) Frequency (%) <5 14 (7.7) <500 99 (54.7) <10 126 (69.7) Over 5 – 10 16 (8.8) 501 - 1000 15 (8.3) Over 10 - 20 6 (3.3) Over 10 – 15 25 (13.8) 1001 - 1500 9 (5.0) Over 20 - 30 8 (4.4) Over 15 - 20 46 (25.5) 1501 - 2000 11 (6.1) Over 30 – 40 8 (4.4) Over 20 80 (44.2) Over 2000 47 (25.9) Over 40 33 (18.2) Ratio of Export (%) Frequency (%) Respondent Frequency (%) Industry type Frequency (%)

<25 30(16.6) CEO 25(13.8) Electrical Company 40 (22.1) Over 25 – 50 37(20.4) Environmental Director 50(27.6) Electronics Company 80 (44.2) Over 50 – 70 46(25.4) R&D Director 63(34.8) Information

Company 61 (33.7) Over 70 68(37.6) Marketing Director 43(23.8) n= 181

FIGURE 1 the Framework of This Research

1. Corporate Environmental Policy 2. R&D strength 3. Cross-Functional Integration a. Environmental Performance b. Financial Performance Family firms (H1, H2, H3)

TABLE 2

Factor Analyses for Organizational Response

Factor name (% of variance

explained)

Measure items Selected sources Variable loading Reliability Cross-functional integration (43.813%)

In our green new product development project, marketing, R&D and environmental department: 1. Rarely/regularly communicate for green new

product development.

2. Rarely/regularly share information on customers.

3. Rarely/regularly share information about competitors’ products and strategies.

4. Seldom/fully cooperate in establishing green new product development goals and priorities.

5. Seldom/fully cooperate in generating and screening green new product ideas and testing concepts.

6. Seldom/fully cooperate in evaluating and refining green new product.

7. Are inadequately/fully represented on our product development team.

8. Technological knowledge and market knowledge are never/fully integrated in our green product development.

Li & Calantone (1998) .794 .818 839 .814 .835 .839 .805 .808 0.960 Corporate environmental policy (34. 578%)

1. Written environmental product policy exists in the company.

2. Corporate environmental policy explicitly addresses the environmental issues in NPD decisions.

3. We measured risk related environmental issues.

4. We measured compliance-related impacts of products.

5. Top management support for developing green responsive packaging.

6. Top management support for developing green responsive products.

Pujari et al. (2003) .802 .837 .857 .837 .749 .778 0.943

TABLE 3

Factor Analysis for Success of Green Product Development

Factor name (% of variance explained)

Measure items Selected sources Variable loading Reliability Financial performance (67.36%)

1. As compared to yours competitors, your GNPD project’s return is lower/higher. 2. As compared to yours competitors, your

GNPD project’s growth is lower/higher. 3. As compared to yours competitors, your

GNPD project’s sales growth is lower/higher.

4. As compared to yours competitors, your GNPD project’s market share is lower/higher. Judge and Douglas (1998) 0.695 0.885 0.941 0.852 0.902 Environmental performance (17.21%)

1. The company chooses the materials of the product that produce the least amount of pollution for conducting the product development or design.

2. The company chooses the materials of the product that consume the least amount of energy and resources for conducting the product development or design.

3. The company uses the fewest amount of materials to comprise the product for conducting the product development or design.

4. The company would circumspectly deliberate, whether the product is easy to recycle, reuse, and decompose for conducting the product development or design. Chen et al. (2006) 0.907 0.880 0.810 0.797 0.886 TABLE 4

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation for Study Variables

Variables X1 X2 X3 Y1 Y2 X1 R & D strength 1.000 X2 Corporate Policy .524 1.000 X3 Cross-functional integration .505 .669 1.000 Y1 Environmental performance .430 .617 .617 1.000 Y2 Financial performance .544 .591 .585 .672 1.000 Means 5.179 5.666 5.410 5.649 5.166 Standard deviations .876 .888 .901 .935 1.076 n=181

TABLE 5

Result of Multiple Regression Analyses for Green Product Innovation Performance

Green product innovation performance

Model C Model D Beta p Beta p Age -.062 .293 -.044 .419 Size -.037 .527 -.048 .374 EB .194 .020 .234 .003 CEP .212 .008 .437 .000 CFI .239 .003 -.003 .971 R&D .178 .016 .250 .005 Family firms (n= 65) .138 .021 .084 .137

CEP *Family firms -.354 .000

CFI *Family firms .346 .000

R&D *Family firms -.218 .006

Sig. .000 .000 R2 Adj. .414 .505 △R2 Adj. .091 Sig. F Change .000 Note:

EB: Environmental benchmarking, CEP: Corporate environmental policy CFI: Cross-functional integration, R&D: R&D strength,

TABLE 6

Result of Multiple Regression Analyses for Financial Performance

Financial performance Model E Model F Beta p Beta p Age .050 .364 .054 .300 Size -.063 .253 -.071 .171 EB .201 .010 .220 .003 CEP .224 .003 .385 .000 CFI .174 .021 -.053 .545 R&D .201 .004 .239 .005 Family firms (n=65) -.145 .010 -.169 .002

CEP *Family firms -.236 .002

CFI *Family firms .335 .000

R&D *Family firms -.150 .028

Sig. .000 .000 R2 Adj. .493 .542 △R2 Adj. .049 Sig. F Change .000 Note:

EB: Environmental benchmarking, CEP: Corporate environmental policy CFI: Cross-functional integration, R&D: R&D strength,