pp. 181-206, No. 3, November 2001 College of Humanities and Social Sciences Feng Chia University

A Comparison of Taiwanese and Japanese

Appreciation of English Jokes

Chao-chih Liao*, Goh Abe**

Abstract

As shown in their languages, Japanese society is more hierarchical than Taiwanese society. A more hierarchical society produces less humorous people (Lin, 1976; Abe, 1995). This study compares Taiwanese and Japanese appreciation of other- versus self-deprecating jokes according to 200 Japanese and Taiwanese university students’ evaluation on a seven-point Likert scale—1 for ‘extremely dry’ and 7 for ‘extremely interesting’—to 11 English jokes.

After gathering data from more than 500 students, we discarded those who are relations of lawyers, then divided the rest into four piles—Japanese male, Japanese female, Taiwanese male and Taiwanese female—shuffled them and used the first 50 sets of responses from each pile for this study. Two-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) together with post-hoc Scheffe’s test found that ethnicity plays a more significant role than gender in different appreciation of both self- and other-deprecating jokes. In three jokes, Japanese and Taiwanese appreciation levels are not significantly different. In the other eight jokes, Taiwanese appreciate them more than Japanese. Taiwanese are more eager than Japanese to understand an incomprehensible joke; in both nations females are significantly more eager than males. Verbal jokes please Japanese less than Taiwanese.

Keywords: Self-deprecating jokes, other-deprecating jokes, humor, Japan, Taiwan

*Associate Professor, Foreign Languages and Literature Teaching Section, Feng Chia University. ** Professor, Department of Literature, Tokushima Bunri University.

1. Introduction

It seems cross-cultural humor study has become the trend in the humorology field. In the 2001 International Humor Conference of the International Society for Humor Studies (ISHS) hosted by University of Maryland, there were at least the following cross-cultural papers presented: Davies (2001), El-Arousy (2001) and Schulten (2001).

Few studies have drawn Taiwanese and Japanese together to compare their humor. Lin (1937) compared Chinese and Japanese based on his intuition and experience of reading Japanese and Chinese literature. Liao and Abe (2000) was the first quantitative study comparing Japanese and Taiwanese sense of humor. The current study tries to bring the university students from the two nations together to do a quantitative study on their appreciation of English jokes.

Wells (1997) discussed Japanese humor from the literary people’s viewpoints. She did not review any quantitative studies; perhaps there had not been such studies. Abe and Liao (2001) found that more Chinese than Japanese feel that ‘a person with a sense of humor does not downgrade others’ (84% to 58%). Based on this, in this study we expect Japanese to feel #1-#5 more interesting than Chinese.

As shown in their languages, Japanese society is more hierarchical than Taiwanese society. A more hierarchical society produces less humorous people (Lin, 1976; Abe, 1995). This study compares Taiwanese and Japanese appreciation of other- versus self-deprecating jokes according to a seven-point Likert scale to 11 English jokes by 200 university students in Taichung Taiwan and Kagawa Japan. The Japanese students (average age of 20.75 years, SD=1.24, range 19-28) studied in the colleges of medicine and business, not in the departments of literature and/or linguistics. The Taiwanese students (average age of 21.4 years, SD=4.71, range 18-49) studied in the colleges of construction and business.

The English jokes were first read by the subjects (Ss) themselves for 20 minutes and then explained in Japanese by Abe and in Mandarin by Liao in order for them to fill in the seven-point scale, 1 ‘extremely dry’ and 7 ‘extremely interesting’. After gathering data from more than 500 students, we discarded those who have lawyer relations (27 Japanese and 38 Taiwanese responses), then divided the rest into four piles—Japanese male (JM), Japanese female (JF), Taiwanese male (TM) and Taiwanese female (TF)—shuffled them and used the first 50 sets of responses from each pile for this study. The reason for discarding the responses of those who have

relations with lawyers is that Liao (1998b: 16) found that those who have attorney relations might feel offended by the law jokes, #1-#5, and feel that they are less funny than those who do not have such relations.

Some readers might suggest us to use 400 responses, not randomly pick up 200, thinking the latter number too small. When 200 is too small, 400 is also not big enough because Taiwan population is 24 million and Japan 124 million. However, in statistics, too many subjects connote wasting data, time and money. Sometimes a group of 25-30 subjects is quite adequate (Hogg and Tanis, 1983). The impracticality of using the whole population in research causes the establishment of departments of statistics for undergraduates and graduates in universities.

Two-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) together with post-hoc Scheffe test was used to draw inferences. When the p-value is equal to or less than 0.05, at least one comparison group is significantly different from one or more other groups. When the p-value is bigger than 0.05 and equal to or less than 0.1, the comparison groups are marginally different from each other. When the p-value is bigger than 0.1, the compared parties are not different from each other. It was found that ethnicity plays a more significant role than gender in different appreciation of both self- and other-deprecating jokes. In three jokes, Japanese and Taiwanese appreciation levels are not significantly or marginally different. Taiwanese appreciate the other eight jokes more than Japanese.

The first five law jokes were extracted from the 22 study items in Liao (1998b). They were among the most favorite 17 jokes, which obtained means larger than the neutral judgement of 4 on the seven-point Likert scale (extremely dry 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 extremely funny). In Liao (1998b), the five jokes were appreciated in the descending order of #5, #3, #4, #1 and #2 (Appendix).

#6-#11 were extracted from Liao (1999) for Taiwanese subjects and adapted from some other ethnic jokes; none are of Chinese or Japanese origin. For example, the original version of #6 (Appendix) is

Two Norwegians, two Swedes, and two Danes were stranded on a desert island. When the rescue party arrived two months later, the Norwegians were fighting, the Danes had formed a cooperative, and the Swedes were still waiting to be introduced.

Davies (1990; 1998: 35-41) might be right to claim that Chinese (Taiwanese) and Japanese lack ethnic humor of stupidity and being canny because historically most

Chinese and Japanese seldom traveled outside their hometown. Where there was no contact, there was no competition and no need to produce such kind of ethnic humor to cope with the tension (Davies, 2000). #7 and #10 for the Taiwanese Ss are Chinese macro self-bragging jokes, for the Japanese are Japanese macro self-bragging jokes. #6 and #11 for the Taiwanese subjects are macro self-deprecating jokes, for the Japanese are Japanese macro self-deprecating jokes. #8 and #9 are Chinese and Japanese micro self-deprecating jokes. The pure micro (personal) level self-deprecating jokes of #8 and #9 were also revised from two items of ethnic jokes. Their original versions are Hindu-deprecating:

#8 A car was involved in an accident in a street. As expected a large crowd gathered. A Hindu newspaper reporter anxious to get his story could not get near the car. Being a clever sort, he started shouting loudly, “Let me through! Let me through! I am the son of the victim.” The crowd made way for him. Lying in front of the car was a donkey.

#9 A huge Hindu got on a train in India, shouted, “I am the son of a lion!” and manhandled a weak and sickly Muslim by pushing him out of his seat. The meek Muslim stood for the whole journey for the better part of a day. Finally the Hindu got up and left the train. As the train started off the Muslim looked out of the window and yelled at the bullying Hindu, “Did your mother go into the jungle or did the lion come to your house?”

2. Literature Review

2.1 Taiwanese versus Japanese: General People's Concepts

Taiwanese and Japanese culture are closely related, because Taiwan and Japan are both in Asia and their cultures have influenced each other at least for more than 1000 years. From 1895 to1945, Taiwan was ruled by Japan. Taiwan has a group of six million Japanese cartoon fans, in their early 30s or younger. In February 2000, a group of Japanese cartoonists were invited to Taiwan to meet their fans. Twelve months later, Japanese cartoonists visited Taiwan again and many Taiwanese fans even dressed themselves up like the characters in the Japanese cartoon series to meet them. The popularity of Japanese cartoonists in Taiwan has made the Taiwan

cartoonists complain that Taiwan is not suitable for the creation of local Chinese cartoons. Taiwanese readers are familiar with the life stories of their Japanese idol cartoonists, while no one seems to know much about Taiwanese ones. A Taiwanese cartoonist said that cartoon creation in Taiwan began much later than did the Japanese one. Many Taiwanese cartoon creators cannot produce such long series of a cartoon story as the Japanese ones. However, he bolsters that the quality of Taiwan cartoon is as good as that of Japan (United Evening News, Feb 19, 2000).

Considering Japanese and Taiwanese humor-related things, the first impression Taiwanese people have about Japanese is that there are many animated Japanese TV cartoon programs in Taiwan. The comic strips department is also among the biggest in Taiwan bookstores and Japanese cartoons are the main stuff. Many Taiwanese university students choose to learn Japanese as the second foreign language because they enjoy reading Japanese comic strips books and watching Japanese TV series. The books and TV series are translated into Mandarin; Taiwanese university students hope to enjoy them in their original language, Japanese. One undergraduate told his parents that he felt sad that they gave birth to him because he is not similar to the characters in the Japanese comic strips—having very thin chins.

Many Chinese might think that they are more humorous than Japanese perhaps because they can tell canned jokes, not because they can create more and better original comic strips or cartoon series; however, telling canned jokes is not a good way for an average person to be funny. When one tells a joke, s/he is, in essence, performing someone else's material (Berger, 1993: 15).

2.2 Japanese versus Taiwanese: Humorologists' Concepts

Lin (1937; quoted in Wells, 1997: 139) and Michael Titze (1998: personal communication [pc]) opined that Japanese and Germans are two melancholy peoples. Chinese humorists (e.g., Lao, 1987 and Dai, 1997) generally think that Chinese are not as humorous as Americans. Yanagita (1967a, b) was unhappy that many foreigners said that Japanese are not humorous. He indicated that Japanese are a people who smile a lot, especially in Kansai. Tokyo people smile only for their friends. The Japanese laugh and smile in anger and hatred; perhaps they smile too much (Don Nelson, 2001: pc). Smile is a social rite (Hearn, 1976). During the Twelfth ISHS International Humor Conference, July 24-27, 2000, the Japanese humorologist Oda proposed that the humorless Japanese backdate to Japanese tradition.

When many Taiwanese say that they have a sense of humor, they often begin to tell a lot of canned jokes—the ‘Have you heard about this one…’ type—to prove it.

However, Japanese may prefer a person to tell jokes happening to the narrator, even when they know that the narrator makes them up (Oshima, 2000).

For Japanese, the rules of humor exist just as the rules of etiquette exist. The rules of humor may be considered part of the rules of etiquette, and like the rules of etiquette, they may be a century or so behind the practice (Wells, 1997). Yanagita (1964, 1967a, 1967b) proposes victimless humor for Japanese.

Liao (1998a) found that ‘a sense of humor’ is formed quite late in the Chinese mind; therefore, many more people at workplace feel that they are more humorous than university undergraduates—84% for elementary school teachers to be humorous and only 59% for university undergraduates (Liao, 1998a: 203, 327). The workplace is more stressed than the students’ life partly because at work one needs to take more responsibility and meet people of various personalities and ages, while at school one interacts mainly with people of similar ages. That people in a more stressed world become more humorous shows that they have learned to cope with stress via more sense of humor.

Allport (1937) studies English people and their personalities, and finds the sense of humor and insight correlate highly; that is, a person with a higher sense of humor also has better insight. Both English and American people think that ‘a sense of humor’ is a person’s important characteristics; therefore, 94% of the British people reported that their sense of humor was as good or better than the average (Allport, 1937: 224)

Oda’s speech made us think about similarities between Japanese and Taiwanese humor. In formal situations both Japanese and Taiwanese try to restrict themselves from laughing. Some Taiwanese university informants indicate that they try not to laugh in public and formal situations because they are afraid of the accusation of inability to control themselves. Japanese also avoid laughing in public and formal situations.

Both Taiwanese and Japanese like playing with pun, regarding it high-class humor. One difference between traditional Chinese and Japanese is that Chinese men are allowed to guffaw, women to giggle. However, Lao (1987) proposed that an elegant gentleman does not guffaw. While in Japan it has long been a virtue for men to refrain from laughing and women to laugh with their mouths only slightly open (Oda, 2000).

Oshima (2000) indicates that Japanese undergraduates appreciate jokes expressed in the first person, such as (1), even if they know they are fictional; they do

not appreciate the joke-teller's jokes, such as (2)1 so much as the former.

(1)My grandpa is eighty-five years old. He loves candies. So I gave him a box of chocolate for Valentine's day. And he ate it all in one day. I was about to tell him, “Grandpa, if you eat so much chocolate at once, you will get toothache…” But I didn't, because he suddenly took all of his teeth out of his mouth. (Source: Oshima, 2000)

(2)The recent technology developed the talking machine. There is a weight measure at Gym that tells weight as you stand on it. When someone stands on the measure, it says, “Pi pi pi…, You are sixty-five kilograms.” When a middle aged woman stood on the measure, it said, “Pi pi pi…, please, one person at a time.” (Source: Oshima, 2000)

Oshima also pointed out that Japanese tell jokes mostly among close friends to show that they are good friends. They tell jokes in the descending frequency of close friends, family members, and co-workers. The purposes of telling jokes in descending frequency are (1) to have more fun, (2) to fix a bad mood, and (3) to ironically criticize. Fudano (2000) found two great difference between Chinese in Shanghai and Japanese in Kansai area (Osaka): (a) when a new teacher tells an unfunny joke, Chinese students do not laugh and Japanese students laugh to be polite; and (b) among close friends, Chinese students laugh in response to unfunny jokes, and Japanese do not.

Lin (1940) pointed out that the big difference in Japanese and Chinese humor is that the Japanese have shown a fine sense of humor in art and literature. Yet in action and in daily life they seem to behave essentially like the humorless Germans. They are clumsy, heavy, stupidly logical and hopelessly bureaucratic. On the other hand, the Chinese are essentially a humorous people in their daily life, and yet in their classical literature the silent chuckle and ticklish laughter seem to be rare (quoted in Wells, 1997: 140).

A major consequence of the behavioral, expressive, and other sociocultural constraints imposed on women is that many common attributes of men’s humor seem to be much less evident or even absent in women's humor. In public domains women seem generally not to engage in verbal duels, ritual insults, practical jokes, and pranks,

1

Readers might argue that (2) is a joke recycled for many times, while (1) is fresher. It might be another reason which makes (1) sound more interesting than (2). However, Liao (2001) shows that

all of which reflect the competitive spirit. Women’s humor generally lacks the aggressive and hostile quality of men’s humor. Men play practical jokes not only on men but also on women (Apte, 1985: 69-70). As women age and reach menopause, they seem to grow bolder, start competing with men openly and freely in all types of humor, and often prove they are equals (Fox, 1977; Apte, 1985: 79). In Korea, a woman beyond menopause is considered to be sexless in the eyes of the people and can therefore do pretty well as she pleases (Osgood, 1951: 114).

3. The Study

In October-December 2000, we distributed eleven English jokes, #1-#11 (shown below and in Appendix) to Japanese and Taiwanese University students. First the Ss were given 20 minutes to read by themselves; then we explained them in Japanese to Japanese Ss and in Mandarin to Taiwanese Ss, respectively, to let them check if their understanding was right and asked them to rate on the dryness-funniness seven-point Likert scale for each joke. Following their rating, we asked two extra questions (S1 and S2; see 3.5) to test what we have hoped to know since we finished our last paper (Liao and Abe, 2000; Abe and Liao, 2001).

This study is both comparative and ethnographic. All the eleven items are either other- or self-deprecating. None of the 200 subjects had lawyer friends or relatives. In this case, #1-#5 are other-deprecating to lawyers; #6 and #11 are self-deprecating at the macro level, #8 and #9 at the micro level. #7 and #10 are self-bragging.

Two-way ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) together with post-hoc Scheffe test was used to examine differences of the four groups—JF, JM, TF and TM. It was found in eight jokes, Japanese and Taiwanese are significantly different in their appreciation level. In the other three, they were not significantly different and served as a norm to show that Taiwanese and Japanese might have used the same criterion to evaluate the jokes. In the examples, #2, #3 and #11 mean the items appeared second, third, and eleventh in a series of 11 jokes (Table 1).

3.1 The Items Where Japanese and Taiwanese Appreciation not

Significantly Different

The fact that the Japanese and Taiwanese university students evaluate the following three items about the same in funniness/dryness shows that there are at least some similarities between the two peoples. Table 1 shows the three jokes from the

most funny to the least are #3, #11 and #2. When people from the two ethnic groups feel them interesting in the same descending order, it is reasonable to predict about universality in joke appreciation. Since #2 and #3 were also tested by Liao (1998b), we find that the finding here is consistent with the former finding with another independent group of Taiwanese university students that #3 is appreciated more than #2. In #3, the witness took the attorney's question literally, which makes it so funny.

#2. Q: “How was your first marriage terminated?” A: “By death.”

Q: “And by whose death was it terminated?”

#3. Q: “All your responses must be oral, OK? What school did you go to?” A: “Oral.”

#11. For a long time, Chinese (Japanese) couples resisted the idea of divorce, but times change. Recently in Ping-tong County (Nara) a Chinese (Japanese) couple filed for divorce. The woman was testifying & explaining her "bad marriage" to the Judge. She said, “That's my side of the story, your Honor, now let me tell you his.”

Table 1: The Means (SD) for #2, #3 and #11 of the jokes

Grand Mean JF JM TF TM

#2 2.05 (1.37) 2.20 (1.37) 1.92 (1.24) 1.86 (1.28) 2.20 (1.55) #3 3.22 (1.37) 3.70 (1.50) 2.84 (1.78) 3.06 (1.97) 3.26 (1.96) #11 2.44 (1.50) 2.54 (1.43) 2.22 (1.29) 2.50 (1.50) 2.50 (1.76)

The three items are all related to law; the first two are other-deprecating to attorneys and the last one is Taiwanese- and Japanese- self-deprecating to Taiwanese and Japanese, respectively, at a macro level. The contents of #11 were intentionally composed to make it an ethnic joke2. In #11, the words in the parentheses are used to replace the previous words for distributing to Japanese Ss. The same rule also applied to #6, #7, #9 and #10.

2

3.2 The Items Where Japanese and Taiwanese Appreciation Significantly

Different

#1. Q: “You say the stairs went down to the basement?” A: “Yes.”

Q: “And these stairs, did they go up also?”

#4. Q: “Are you qualified to give a urine sample?” A: “I have been since early childhood.”

#5. Q: “Doctor, before you performed the autopsy, did you check for a pulse?” A: “No.”

Q: “Did you check for blood pressure?” A: “No.”

Q: “Did you check for breathing?” A: “No.”

Q: “So, then it is possible that the patient was alive when you began the autopsy?”

A: “No.”

Q: “How can you be so sure, Doctor?”

A: “Because his brain was sitting on my desk in a jar.” Q: “But could the patient have still been alive nevertheless?”

A: “It is possible that he could have been alive and practicing law somewhere.”

#6. Two Chinese, two Japanese, and two Koreans were stranded on a desert island. When the rescue party arrived two months later, the Chinese (Japanese) were fighting, the Japanese (Chinese) had formed a cooperative, and the Koreans were still waiting to be introduced.

#7. The Chinese, the Japanese, and the Korean were arguing about which country was most advanced in medicine.

“Well, in our hospitals,” the Korean bragged, “we had a lady who had lost her arm. We put in a mechanical arm, and now it works just as if it were her own!” “Hah, that's nothing,” said the Japanese (Chinese). “In our hospitals, we had a person without a heart. We put in an artificial one, and now he is running for the Olympics!”

“Hahaha,” said the Chinese (Japanese). “We had a person who had gotten his head chopped off. We put on a cabbage, and now he is in the Legislative Yuan (parliament)!”

#8. A car was involved in an accident in a street. As expected a large crowd gathered. As a newspaper reporter, anxious to get my story, I could not get near the car. Being a clever sort, I started shouting loudly, “Let me through! Let me through! I am the son of the victim.” The crowd made way for me. Lying in front of the car was a donkey.

#9. A huge man got on a train in Kaohsiung (Osaka), shouted, “I am the son of a lion!” and manhandled me, weak and sickly, by pushing me out of my seat. I stood for the whole journey for the better part of a day. Finally the man got up and left the train. As the train started off, I looked out of the window and yelled at the bullying man, “Did your mother go into the jungle or did the lion come to your house?”

#10. Chinese (Japanese) Mothers don't differ from any other in the world when it comes to bragging about their sons. My Mother, trying to out-do another when it came to opportunities available to their just graduated-from-college sons, said, “My Chih-wei (Zaki) has had so many fine interviews; his resume is now in its fifth printing.”

Table 2: The Means (SD) for the jokes where Japanese and Taiwanese appreciation are significantly different

# Grand Mean JF JM TF TM Significant? (F-value) #1 2.24 (1.53) 2.10 (1.40) 1.92 (1.43) 2.10 (1.02) 2.84 (1.98) N & N*G (3.73) #4 2.46 (1.58) 2.12 (1.22) 1.92 (1.12) 2.66 (1.59) 3.12 (1.99) N (6.39) #5 3.20 (1.90) 2.80 (1.47) 2.20 (1.21) 4.12 (1.98) 3.86 (2.05) N & G (16.36) #6 2.56 (1.64) 2.46 (1.53) 1.9 (1.22) 3.16 (1.96) 2.70 (1.57) N & G (5.43) #7 3.78 (2.18) 3.00 (1.74) 2.58 (1.87) 4.90 (2.00) 4.64 (2.15) N (17.79) #8 4.67 (1.91) 4.74 (1.83) 3.48 (1.92) 5.66 (1.51) 4.80 (1.76) N & G (13.01) #9 3.31 (1.91) 2.48 (1.33) 2.02 (1.22) 4.46 (1.78) 4.26 (1.95) N (29.94) #10 2.73 (1.70) 2.48 (1.39) 2.28 (1.40) 3.30 (1.87) 2.86 (1.94) N (3.64) N: nation; G: gender; N*G: interaction of Nation and Gender

propose jokes should be self-deprecating, we predicted Japanese to appreciate #1-#5 more. Tables 1 and 2 refute our prediction: Taiwanese appreciate #1, #4 & #5 significantly more than Japanese; they are not significantly different in #2 and #3. In only one item, #1, there is interaction effect between nation and gender—i.e., Taiwanese males enjoy it especially more than Japanese males. There must be some Japanese culture-specific thing which made them appreciate other-deprecating #1-#5 less than Taiwanese. Japanese humor scholar Yanagita (1964, 1967a, 1967b) proposal of victimless humor might explain why Japanese appreciate #1-#5 less than Taiwanese. They do not appreciate jokes using attorneys or anyone else as victims.

Table 2 shows that Taiwanese appreciated all the eight jokes more than Japanese males and females. An alternative explanation is that Japanese appreciate jokes expressed in the first person as Oshima’s first example aforementioned. They do not enjoy joke-tellers’ jokes, like the eight items written for them to read for 20 minutes before Abe’s and Liao’s explanation. Females appreciate #5, #6 and #8 significantly more than males. Obviously nation plays a more significant role than gender in the joke appreciation because nation factor is important in eight items and gender in only three. The common trait with #5, #6 and #8 is that they are derogatory, not bragging.

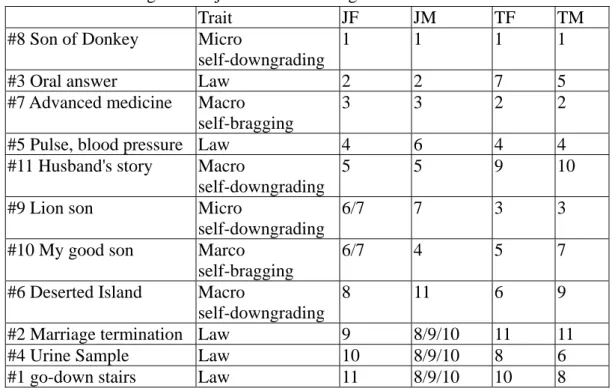

Table 3: Interesting canned jokes in descending order

Trait JF JM TF TM

#8 Son of Donkey Micro

self-downgrading

1 1 1 1

#3 Oral answer Law 2 2 7 5 #7 Advanced medicine Macro

self-bragging

3 3 2 2

#5 Pulse, blood pressure Law 4 6 4 4 #11 Husband's story Macro

self-downgrading

5 5 9 10

#9 Lion son Micro

self-downgrading

6/7 7 3 3

#10 My good son Marco self-bragging

6/7 4 5 7

#6 Deserted Island Macro

self-downgrading

8 11 6 9

#2 Marriage termination Law 9 8/9/10 11 11 #4 Urine Sample Law 10 8/9/10 8 6 #1 go-down stairs Law 11 8/9/10 10 8

The Taiwanese females and males rate the five law jokes (Table 3) in the same appreciation order as those in Liao (1998b). This shows that Taiwanese, at different

times, follow the same principle in judging if a joke is interesting or dry. The Taiwanese order of appreciation of the five law jokes is not the same as that of the Japanese men and women. The two genders in Japan appreciate them in roughly the same order. Both the ANOVA test shown in Table 2 and the ranking order in Table 3 demonstrate that in joke appreciation the ethnicity factor is more important than the gender factor.

For both Japanese and Taiwanese, #8 ‘Son of Donkey’ is appreciated highest; this shows that the two ethnic groups share some common values about joke appreciation. Perhaps both like self-deprecatory jokes. We keyed-in the rank data in Table 3 to get the high correlation between JF and JM, as well as between TF and TM (gray areas in Table 4), indicating humor as the result of cultural perceptions. Both men and women from the same culture have internalized their social structure, behavior patterns & value system and thus judge similarly in joke appreciation (Apte, 1985: 16-17).

Table 4 The r-value (p-value) of correlation between the four groups

JM TF TM

JF 0.89 (0.000) 0.68 (0.02) 0.65 (0.03) JM 0.57 (0.07) 0.62 (0.04)

TF 0.88 (0.000)

3.3 Self-deprecating at the Micro- and Macro-level

#1-#5 were extracted from Liao (1998b), #6-#11 from Liao (1999). The latter items were adapted to be suitable for Japanese and Taiwanese to be self-deprecatory or self-bragging in macro (national) or micro (personal) level. #8 and #9 are self-deprecating on the personal level, which should be the favorites of Lao (1987) and Dai (1996) because they promoted self-deprecating humor though they had difficulty practicing it (Liao, 1999).

Following the micro-level self-deprecating jokes, #8 and #9, we asked Ss to answer Q8.1 and Q9.1:

Q8.1: If you were this reporter, would you tell the story to your friends? (1. Sure; 2. No, it's too shameful)

Q9.1: If you were the weak and sickly person, you would (1. Yell like the speaker in the joke; 2. Keep quiet, speak softly to yourself the sentence the speaker said; 3. Argue with the lion son on the train that the seat is yours.)

Table 5: Japanese versus Taiwanese responses to Q8.1

Sure No. Too shameful Total

JF 37 (74%) 13 (26%) 50

JM 38 (76%) 12 (24%) 50

TF 34 (58%) 16 (32%) 50

TM 26 (52%) 24 (48%) 50

Total 135 (67.5%) 65 (32.5%) 200 Chi-square value = 8.091 (DF = 3; p-value = 0.044)

Post-hoc Chi-square value to JF, JM and TF is 0.873 (DF=2; p-value = 0.646)

Table 6: Japanese versus Taiwanese responses to Q9.1

Yell Softly Argue Total JF 10 (20%) 33 (66%) 7 (14%) 50

JM 16 (32%) 27 (54%) 7 (14%) 50 TF 5 (10%) 16 (32%) 29 (58%) 50 TM 7 (14%) 19 (38%) 24 (48%) 50 Total 38 (19%) 95 (47.5%) 67 (33.5%) 200

Chi-square value = 38.237 (DF = 6; p-value = 0.000); χ2= 1.062 (DF=2; p-value =0.588) for TF and TM; χ2 = 1.985 (DF=2; p-value = 0.371) for JF and JM; χ2= 34.438 (DF=2; p-value =0.000) for the two groups: [JF & JM] as one and [TF & TM] as the other.

Table 5 shows that JF & JM are roughly the same: 74% or 76% would surely tell the story to their friends. They commented that it is so funny and they hope to share with friends. Only 58% of TF and 52% of TM would. TM is the group which value their face so much that 48% think that it is too shameful to tell the embarrassing story to their own friends. Taiwanese males cannot avoid the face concept even in the world of humor, which is a contrast to the serious world (Michael Titze, 1998: pc). All the other three groups are not significantly different from each other (p-value being 0.646). A post-hoc Chi-square test to JF and JM in Table 6 shows no significant difference between the two genders, nor is there statistically significant difference between TF and TM. The high chi-square value below Table 6 thus reflects the huge difference between Taiwanese and Japanese (χ2= 34.438, DF=2, p-value =0.000). More Chinese would argue with the lion son. This might be the influence of Taiwanese politics: legislators fight orally and physically as shown on TV news.

Many Japanese literary people propose victimless humor (Wells, 1997), while Taiwanese humorologists such as Lao (1987) and Dai (1997) advocate self-deprecating humor. In analogy, Japanese should care more about face-work (Goffman, 1955) than Taiwanese, for victimless humor is stricter than

self-deprecating humor. The data in Table 5 is contradictory with what is enthusiastically advocated in Taiwanese society: Taiwanese (especially men) care more about face-work. The humor etiquette set by prescriptive humorologists is too much ahead of the social practice. Taiwanese males are much afraid that their own face may not be maintained even in the humorous world. To become humorous, one must learn to admit one’s own mistake, to self-deprecate on purpose—i.e., to stop keeping one’s own face intentionally. Japanese literary people have been very moral to promote victimless humor in order not to hurt anyone, including self. The current study might partly hint most Japanese (75%) have been able to downgrade themselves. In pursuing excellence, they propose victimless humor. Reading Japanese writer Kin-ichi Ishikawa’s (born in 1895) humorous works in A Book of Thoughts (1958) and Lin Yutang’s (1895-1976) selections (1976), we find the strongly self-deprecating writing genre of Ishikawa and the non-self-deprecating writing of Lin.

#7 and #10 are self-bragging on the ethnic level. #7 for Chinese is self-bragging for both Chinese and Japanese. All three medical techniques are impossible and thus violate Grice’s maxim of quality (Grice, 1975). It ridicules brainless parliamentary members in the two countries. Taiwanese appreciate #7 much more than Japanese because it is so true for Chinese. Chinese feel ashamed that the legislators physically fight each other. For Japanese, it is an unlikely joke. #6 is more inclusive of the university students. When Taiwanese Ss read them, they feel ashamed that Taiwanese/Chinese do not cooperate well and they think they need to change the bad habits or custom. The two items might be more relevant to Chinese than Japanese. #6 and #11 are self-deprecating on the ethnic level.

A joke treating or thinking of other cultures and people as inferior is one way of strengthening self-image (Apte, 1985: 142). However, when jokes are self-directed, they offer self the chance of reflection, or social control (Barron, 1950; Burma, 1946; Obrdlik, 1942; Stephenson, 1950-51). Even seemingly self-disparaging humor strengthens ethnocentrism, primarily because traits seen as negative by outgroups are viewed as positive by ingroups (Dundes, 1971; Ehrlich, 1979).

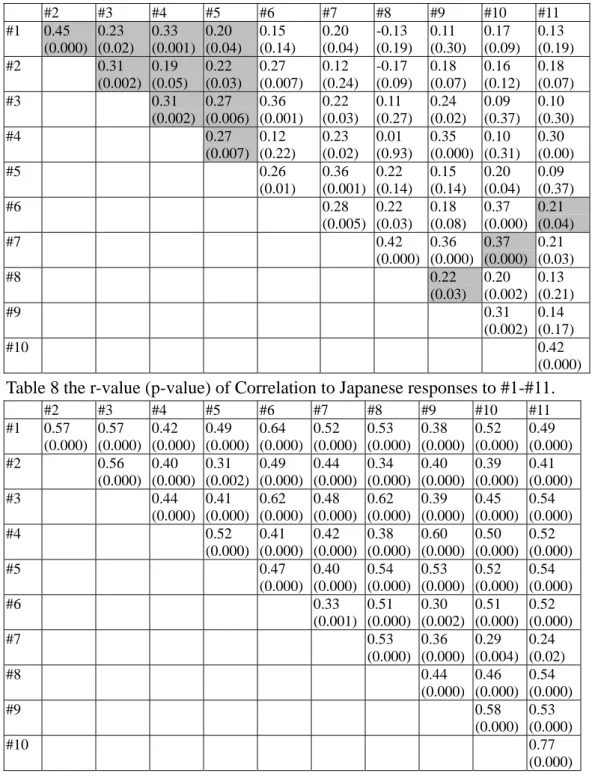

3.4 Appreciation Correlation

Table 7 tabulates the Pearson Product-Moment Correlations of all possible pairs of Taiwanese Ss’ appreciation of the jokes. Concerning the attorney-deprecating jokes, #1-#5, most of the cells (except that for #2 and #4; gray areas at the intersections of #1-#5) show the p-value less than 0.05; in other words, when one item of attorney-deprecating joke is felt interesting, the other four items are too. The two

self-bragging jokes, #7 and #10, also enjoy high correlation (r=0.36606; p=0.0002), so do the two macro-level self-deprecating jokes, #6 and #11 (r=0.20688; p=0.0389), and the two micro-level self-deprecating jokes, #8 and #9 (r=0.22171; p=0.0266). Compared with Table 7, Table 8 reveals the much higher correlation in the Japanese appreciation of the eleven jokes. The Japanese, as a group, equally feel the jokes drier or funnier than the Taiwanese.

Table 7 the r-value (p-value) of the Pearson Product-Moment Correlation to Taiwanese responses to #1-#11. #2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 #8 #9 #10 #11 #1 0.45 (0.000) 0.23 (0.02) 0.33 (0.001) 0.20 (0.04) 0.15 (0.14) 0.20 (0.04) -0.13 (0.19) 0.11 (0.30) 0.17 (0.09) 0.13 (0.19) #2 0.31 (0.002) 0.19 (0.05) 0.22 (0.03) 0.27 (0.007) 0.12 (0.24) -0.17 (0.09) 0.18 (0.07) 0.16 (0.12) 0.18 (0.07) #3 0.31 (0.002) 0.27 (0.006) 0.36 (0.001) 0.22 (0.03) 0.11 (0.27) 0.24 (0.02) 0.09 (0.37) 0.10 (0.30) #4 0.27 (0.007) 0.12 (0.22) 0.23 (0.02) 0.01 (0.93) 0.35 (0.000) 0.10 (0.31) 0.30 (0.00) #5 0.26 (0.01) 0.36 (0.001) 0.22 (0.14) 0.15 (0.14) 0.20 (0.04) 0.09 (0.37) #6 0.28 (0.005) 0.22 (0.03) 0.18 (0.08) 0.37 (0.000) 0.21 (0.04) #7 0.42 (0.000) 0.36 (0.000) 0.37 (0.000) 0.21 (0.03) #8 0.22 (0.03) 0.20 (0.002) 0.13 (0.21) #9 0.31 (0.002) 0.14 (0.17) #10 0.42 (0.000)

Table 8 the r-value (p-value) of Correlation to Japanese responses to #1-#11.

#2 #3 #4 #5 #6 #7 #8 #9 #10 #11 #1 0.57 (0.000) 0.57 (0.000) 0.42 (0.000) 0.49 (0.000) 0.64 (0.000) 0.52 (0.000) 0.53 (0.000) 0.38 (0.000) 0.52 (0.000) 0.49 (0.000) #2 0.56 (0.000) 0.40 (0.000) 0.31 (0.002) 0.49 (0.000) 0.44 (0.000) 0.34 (0.000) 0.40 (0.000) 0.39 (0.000) 0.41 (0.000) #3 0.44 (0.000) 0.41 (0.000) 0.62 (0.000) 0.48 (0.000) 0.62 (0.000) 0.39 (0.000) 0.45 (0.000) 0.54 (0.000) #4 0.52 (0.000) 0.41 (0.000) 0.42 (0.000) 0.38 (0.000) 0.60 (0.000) 0.50 (0.000) 0.52 (0.000) #5 0.47 (0.000) 0.40 (0.000) 0.54 (0.000) 0.53 (0.000) 0.52 (0.000) 0.54 (0.000) #6 0.33 (0.001) 0.51 (0.000) 0.30 (0.002) 0.51 (0.000) 0.52 (0.000) #7 0.53 (0.000) 0.36 (0.000) 0.29 (0.004) 0.24 (0.02) #8 0.44 (0.000) 0.46 (0.000) 0.54 (0.000) #9 0.58 (0.000) 0.53 (0.000) #10 0.77 (0.000)

3.5 Japanese versus Taiwanese Sense of Humor

For comparison sake, following the seven-point Likert scale of appreciation to #1-#11, we changed to a five-point one for S1 and S2, to make it the same as Liao & Abe (2000) and Abe & Liao (2001), where we had S2 with the five-point Likert scale. In S1, there are significant differences in both ethnic and gender factors (no interaction effect between nation and gender)—i.e., Taiwanese like more than Japanese to have an incomprehensible joke explained, females do more than males.

S1. It is good that someone explains a joke to me when I don’t understand it. Strongly disagree 1 2 3 4 5 Strongly agree

S2. A person with a sense of humor is able to react quickly to people’s words and understand the joke without the joke-teller explaining the joke more explicitly.

Strongly disagree 1 2 3 4 5 Strongly agree

Table 7: Means (SD) for S1 and S2

# Grand mean JF JM TF TM Significant? S1 3.47 3.32 (1.13) 2.82 (1.53) 4.18 (1.24) 3.54 (1.31) N & G

S2 3.69 3.84 (1.06) 3.18 (1.41) 3.82 (1.37) 3.92 (1.37) N N: Nation; G: Gender

Responses to S2 are what we have wanted to know. Liao and Abe (2000) and Abe and Liao (2001) found that out of context Japanese and Taiwanese are not significantly different in agreeing to the statement; on the five-point scale, they get the grand mean of 4.49. The Japanese women got the mean of 4.56, the Japanese men 4.52, the Taiwanese women 4.48 and the Taiwanese men 4.40. Most people agree to the statement; 100%, 98%, 96% and 92%, respectively, of the four groups chose 3 or a higher number. However, in this study, we offer context of the 11 English jokes for them to read alone. Frustrated for not fully understanding them, they changed their attitudes. The grand mean drops significantly to 3.69.

Women in both ethnic groups try to seek more understanding of an incomprehensible joke. They are not supposed to actively produce a lot of humor, but expected to show their appreciation of humor produced (usually by men). To show appreciation is a kind of showing 'I am inferior to' the producer. Men and women have different social status, and women on the whole seem to have lower social status than men, especially in the public domain. Those in the inferior social status are

expected to show more appreciation than those in the higher social status. To appreciate is to show deference.

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Books on Japanese humor (Wells, 1997) and Chinese humor (Dai, 1997; Lao, 1987) strongly imply that Chinese and Japanese scholars are the same: very critical of their own people. Therefore, Chinese think that Chinese lack a sense of humor and Japanese do too, respectively. Lin (1974) was an exception to find that Chinese have a very good sense of humor.

Lin (1937) compared the national characters of various countries according to their share of realism (R), idealism or dreams (D), sense of humor (H) and sensitivity (S): R3 D2 H2 S1 = The English R2 D3 H3 S3 = The French R3 D3 H2 S2 = The Americans R3 D4 H1 S2 = The Germans R2 D4 H1 S1 = The Russians R2 D3 H1 S1 = The Japanese R4 D1 H3 S3 = The Chinese.

Where 4 was ‘abnormally high’, 3 was ‘high’, 2 was ‘fair’ and 1 was ‘low’. Lin’s ideal was R3 D2 H3 S2.

Our tentative conclusion is that Taiwanese enjoy story-tellers’ jokes more than Japanese. To tell this kind of jokes to Taiwanese might be more rewarding than to Japanese. Taiwanese are more eager to understand an incomprehensible joke than Japanese. Taiwanese are better joke receivers than Japanese. The nation/ethnic factor is more important than the gender factor in comparing Japanese and Taiwanese appreciation of jokes, which supports the finding in Abe & Liao (2001) that nation/ethnic factor is more important than the gender factor in comparing Japanese and Taiwanese sense of humor. We hope the comparative study will increase cross-cultural understanding for people who need to contact both Taiwanese and Japanese.

Though Japanese literary people advocate victimless jokes and Taiwanese advocate self-deprecating jokes, there is no evidence to prove that Taiwanese appreciate self-deprecating jokes (#6, #8, #9 and #11) more than other-deprecating jokes (#1-#5). Taiwanese humorologists (Dai, 1997; Lao, 1987) propose

self-deprecating jokes, partly because they have read few ideas about Japanese humor (Wells, 1997) or throughout Chinese history, there are many more other-deprecating jokes, as shown in their fixed four-character idioms, such as Hsiao-shih-liao-liao (小 時了了) or Tzi-hsiang-mao-dun (自相矛盾). In Hsiao-shih-liao-liao, Kong Rong (孔 融) laughed at a friend of his father; in Tzi-hsiang-mao-dun, Hanfeitzi (韓非子) laughed at the self-contradictory vendor of spears and shields.

As shown in their languages, Japanese society is more hierarchical than Taiwanese society. A more hierarchical society produces less humorous people (Lin, 1976; Abe, 1995). Abe (1995) pointed out that in Japanese society, one does not have to resort to the use of humor as social lubrication. In the highly defined public context of Japanese culture individuals are placed within hierarchy not requiring humorous explanations or comic relief. In Taiwanese society, more and more teachers, administrators and governmental officials try clowning or verbal humor to catch the attention of audience and mass media. The findings that Taiwanese appreciate more other- and self-deprecating jokes might explain why the national President, Mayors, schoolmasters and teachers practice more humor. Taiwanese society is not so high-context as Japanese, though both are in the high-context category, compared with American society (Lam, 1997: 5)

About humor-related ideas such as smiling and laughter, Taiwanese, in watching Japanese TV programs, generally cannot tolerate or understand why in receiving bad news (of death), the hostess can smile. Taiwanese culture patterns its people to cry or sob on hearing the news of a relative’s death. From Table 5, we conclude that Japanese are more self-deprecatory than Taiwanese. If we grade humor from low class to high in the following order: other-deprecating, self-deprecating and victimless, Japanese might be of higher class than Chinese because Japanese men of letters are promoting victimless humor (Wells, 1997). The Japanese humor etiquette is victimless and that of Chinese humor is mid-way between other-deprecating and victimless—self-deprecatory. Our expectation that Japanese feel #1-#5 more interesting than Chinese is not verified.

5. Limitations

In Japan, we collected data from undergraduates studying in Kagawa; in Taiwan, from those studying in Taichung. However, the Ss are from all parts of Japan and Taiwan. Though the spirit of statistics is to infer from a relatively small number of subjects, further studies on more extensive area to cover all Japan and Taiwan are

welcome.

Japanese and Taiwanese appreciate #2, #3 and #11in the same order and degree of funniness. Besides the relative freshness of the jokes and/or the contrastive idea of humor competence versus joke competence (Carrell, 1997), there should be some universality in joke appreciation. The explanatory adequacy is not offered here. We hope someday we or someone else is able to proffer.

The studied jokes show the obvious contrast between Japanese and Taiwanese appreciation levels. They also show some high correlation between the two Asian ethnic groups. It is believed that the appreciation levels between a western nation and Japanese/Taiwanese would differ even more greatly; a further study on this aspect is needed.

References

Abe, Goh. 1995. The Function of Humor in Japan and the U. S.—An Alternative Interpretation of Humor Theories. Language and Culture, Centenial Issue for

Celebration of Tokushima Bunri University. Tokushima Bunri Univeristy

Press.Pp.103-119.

Abe, Goh. 2001. Ritual Performance of Laughter in Japan. Paper presented at 2001 International Humor Conference of the International Society of Humor Studies. July 6-9. University of Maryland.

Abe, Goh and Chao-chih Liao. 2001. A Comparative Analysis of Taiwan-Chinese and Japanese Sense of Humor. Journal of Tokushima Bunri University. No. 61. Pp. 21-30. Allport, Gordon W. 1937. Personality: A Psychological Interpretation. London:

Constable and Company Ltd.

Apte, Mahadev L. 1985. Humor and Laughter: An Anthropological Approach. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Barron, M. L. 1950. A Content Analysis of Intergroup Humor. American Sociological Review 15: 88-94.

Burma, J. H. 1946. Humor as a Technique in Race Conflict. American Sociological Review. 11: 710-715.

Carrell, Amy. 1997. Joke competence and humor competence. Humor 10.2, 173-185. Dai, Chen-zhi. 1997. Are you an expert of humor? Vol. 2. Taipei: China Times

Publishing Co.

Davies, Christie. 1998. Jokes and their relation to Society. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Davies, Christie. 2001. Understanding Jewish Jokes by Studying Scottish Jokes. Paper

presented at 2001 International Humor Conference of the International Society of Humor Studies. University of Maryland. July 6-9.

Dundes, A. 1971. A Study of Ethnic Slurs: The Jew and the Polack in the United States. Journal of American Folklore. 84: 186-203.

Ehrlich, H. J. 1979. Observations on Ethnic and Intergroup Humor. Ethnicity 6: 383-398.

El-Arousy, Nahwat A. 2001. Humor in Affective Situations: A Contrastive Study of Arabic and English. Paper presented at 2001 International Humor Conference of the International Society of Humor Studies. University of Maryland. July 6-9. Fox, G. 1977. “Nice Girl”: Social Control of Women through Value Construct. Signs 2

Fudano, Kazuo. 2000. The Comparison of Laugh Behaviors between Japan and China-Based on the Questionnaires of the University Students in Osaka and Shanghai. Paper presented at the 12th International Humor Conference. Osaka, Japan: Kansai University. July 24-27.

Goffman, Irvin. 1955. On face-work: an analysis of ritual elements in social interaction. Psychiatry 18: 213-2311. Reprinted in Communication in Face to

Face Interaction. John Laver and Sandy Hutcheson. Eds. 1972: 319-63.

Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Grice, H. Paul. 1975. Logic and Conversation. In Peter Cole and Jerry L. Morgan. Eds.

Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech Acts. New York: Academic Press. Pp. 41-58.

Hearn, Lafcadio. 1976. The Japanese Smile. In Charles E. Tuttle Ed. Glimpses of

Unfamiliar Japan. Tokyo, Japan: Tuttle Company.

Hogg, Robert V. and Elliot A. Tanis. 1983. Probability and Statistical Inference. New York: Macmillan.

Ishikawa, Kin-ichi. 1958. A Book of Thoughts. New York: Taplinger Publishing Co., Inc.

Lam, Maria Lai-ling. 1997. Chinese Expatriate Perceptions of U.S-Chinese

Negotiating Styles and Relationships. Ph. D. Dissertation. George Washington

University.

Lao, Kang. 1987. Humorous Life. Taipei: Li-ming Publishers.

Liao, Chao-chih. 1998a. Jokes, Humor and Chinese People. Taipei: Crane.

Liao, Chao-chih. 1998b. Chinese Appreciation of English Law Humor. Studies in

English Language and Literature. No. 4 National Taiwan University of Science

and Technology. Taipei, Taiwan. Pp. 13-20.

Liao, Chao-chih. 1999. Appreciating English Jokes: Self-Deprecating vs Other-Deprecating. Studies in English Language and Literature. No. 5. National Taiwan University of Science and Technology. Taipei, Taiwan. Pp. 1-14. Liao, Chao-chih. 2001. Taiwanese Perceptions of Humor: A Sociolinguistic

Perspective. Taipei: Crane.

Liao, Chao-chih and Goh Abe. 2000. Comparison of Taiwan-Chinese and Japanese Sense of Humor. Paper presented at the 12th ISHS 2000 Conference. Kansai University, Osaka, Japan. July 24-28.

Lin, Yutang. 1937. The Importance of Living. New York: Reynal and Hitchcock Inc. Lin, Yutang. 1940. The Chinese and the Japanese. In With Love and Irony. New York:

John Day Company. Pp. 30-31.

York: Sterling Publishing Co. Inc.

Lin, YuTang. 1976. Selections of Lin Yutang. Taipei: Yuan-cheng. (Chinese)

Obrdlik, J. 1942. Gallows Humor—A Sociological Phenomenon. American Journal

of Sociology. 47: 709-716.

Oda, Shokichi. 2000. The Traditional Japanese Smile and Laughter. Invited speech at the 12th International Humor Conference. Osaka, Japan: Kansai University. July 24-27.

Osgood, C. 1951. The Koreans and Their Culture. New York: Ronald.

Oshima, Kimie. 2000. Style of Humor in Japanese Communication. Paper presented at the 12th International Humor Conference. Osaka, Japan: Kansai University. July 24-27.

Stephenson, R. M. 1950-51. Conflict and Control Functions of Humor. American

Journal of Sociology. 56: 569-574.

Schulten, Paul. 2001. Conventions of Humor among the Greeks and Romans. Paper presented at 2001 International Humor Conference of the International Society of Humor Studies. University of Maryland. July 6-9.

Wells, Marguerite. 1997. Japanese Humour. Oxford: St Antony's College.

Yanagita, Kunio. 1964. Warai no hongan (The Desire for Laughter). Teihon Yanagita

Kunio Shu. Vol. 7. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo.

Yanagita, Kunio. 1967a. Warai no Bungaku no Kigen (The Origins of Humorous Literature). Fuko naru Geijutsu. Tokyo: Chikuma Shobo. Pp. 120-49.

Yanagita, Kunio. 1967b. Warai no Kyoiku—Rigen to Zokushin to no Kankei. Fuko

ru Geijutsu (Education by Laughter—The Relationship between Proverbs and

Appendix

This appendix shows the jokes to Japanese subjects

Recently reported in the Journal of the Massachusetts Bar Association, the following are 5 questions (Items 1-5) actually asked of witnesses by attorneys during trials and the responses given by insightful witnesses:

1. Q: “You say the stairs went down to the basement?” A: “Yes.”

Q: “And these stairs, did they go up also?”

2. Q: “How was your first marriage terminated?” A: “By death.”

Q: “And by whose death was it terminated?”

3. Q: “All your responses must be oral, OK? What school did you go to?” A: “Oral.”

4. Q: “Are you qualified to give a urine sample?” A: “I have been since early childhood.”

5. Q: “Doctor, before you performed the autopsy, did you check for a pulse?” A: “No.”

Q: “Did you check for blood pressure?” A: “No.”

Q: “Did you check for breathing?” A: “No.”

Q: “So, then it is possible that the patient was alive when you began the autopsy?” A: “No.”

Q: “How can you be so sure, Doctor?”

A: “Because his brain was sitting on my desk in a jar.” Q: “But could the patient have still been alive nevertheless?”

6. Two Chinese, two Japanese, and two Koreans were stranded on a desert island. When the rescue party arrived two months later, the Japanese were fighting, the Chinese had formed a cooperative, and the Koreans were still waiting to be introduced.

7. The Chinese, the Japanese, and the Korean were arguing about which country was most advanced in medicine.

“Well, in our hospitals,” the Korean bragged, “we had a lady who had lost her arm. We put in a mechanical arm, and now it works just as if it were her own!”

“Hah, that's nothing,” said the Chinese. “In our hospitals, we had a person without a heart. We put in an artificial one, and now he is running for the Olympics!”

“Hahaha,” said the Japanese. “We had a person who had gotten his head chopped off. We put on a cabbage, and now he is in the parliament!”

8. A car was involved in an accident in a street. As expected a large crowd gathered. As a newspaper reporter, anxious to get my story, I could not get near the car. Being a clever sort, I started shouting loudly, “Let me through! Let me through! I am the son of the victim.” The crowd made way for me. Lying in front of the car was a donkey.

9. A huge man got on a train in Osaka, shouted, “I am the son of a lion!” and manhandled me, weak and sickly, by pushing me out of my seat. I stood for the whole journey for the better part of a day. Finally the man got up and left the train. As the train started off, I looked out of the window and yelled at the bullying man, “Did your mother go into the jungle or did the lion come to your house?”

10 Japanese mothers don't differ from any other in the world when it comes to bragging about their sons. My mother, trying to out-do another when it came to opportunities available to their just graduated-from-college sons, said, “My Zaki has had so many fine interviews; his resume is now in its fifth printing.”

11. For a long time, Japanese couples resisted the idea of divorce, but times change. Recently in Nara a Japanese couple filed for divorce. The woman was testifying & explaining her “bad marriage” to the judge. She said, “That's my side of the story, your Honor, now let me tell you his.”

逢甲人文社會學報第 3 期 第 181-206 頁 2001 年 11 月 逢甲大學人文社會學院