行政院國家科學委員會補助專題研究計畫成果報告

※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※

※

※

※ 委託單驅動市場中流動性提供者之研究

※

※

※

※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※※

計畫類別:R個別型計畫 □整合型計畫

計畫編號:NSC 90-2416-H-004-042-

執行期間:90 年 08 月 01 日至 91 年 07 月 31 日

計畫主持人:李怡宗

共同主持人:

計畫參與人員:高明志

本成果報告包括以下應繳交之附件:

□赴國外出差或研習心得報告一份

□赴大陸地區出差或研習心得報告一份

□出席國際學術會議心得報告及發表之論文各一份

□國際合作研究計畫國外研究報告書一份

執行單位:國立政治大學會計學系

中

華

民

國

91 年

10

月

1

日

委託單驅動市場中流動性提供者之研究

Who Pr ovides Liquidity in an Or der -Dr iven Mar ket?

計畫編號:NSC 90-2416-H-004-042-

執行期限:90 年 08 月 01 日至 91 年 07 月 31 日

主持人:李怡宗 國立政治大學會計學系

共同主持人:

計畫參與人員:高明志 國立政治大學會計學系

一、中英文摘要 世界各國許多證券市場皆屬委託單驅 動市場,在這種型態的交易市場中,投資 人並沒有義務提供流動性,為了了解限價 單在委託單驅動市場所扮演的角色,我們 檢驗不同型態投資人的下單策略,結果發 現在委託單驅動市場中,專業機構投資人 (包括外資、共同基金、國內自營商、國內 公司投資部門)確實有流動性的需求,專業 機構投資人為了轉移風險或結清部位,在 尾盤時會表現得較為積極,其中又以外資 表現得最為積極。在波動性很大的市場, 當沖的投資人及一般散戶會比機構投資人 下更多不具市場性的限價單,他們這樣的 行為與限價單在流動性的提供方面是互相 吻合的,除此之外,大部份投資者在接近 收盤時傾向買股票而不是賣股票,相反 的,當沖投資人則傾向賣股票,因此,我 們得到的結論是,當沖投資者是市場上流 動性的主要提供者。 關鍵詞:委託單驅動市場、限價委託單、 市價委託單、流動性提供者 AbstractMany securities markets are organized as order-driven markets in which participants are not obligated to provide liquidity. To shed some light on the role of limit orders in the order-driven market, we examine the ordering strategies of different types of investors. We found that professional institutional traders including foreign traders, mutual fund managers, domestic competitive traders and domestic corporate investors demand for liquidity in an order-driven

market. Professional institutional traders tend to act aggressively near the close to shift their risk or clear their positions. Among types of institutional traders, QFIIs are the most aggressive ones. The results also indicate that day traders place orders relative passively. In a volatile market, day traders

and individual traders submit more

non-marketable limit orders than institutional traders. Such behaviors of day traders and individual traders are consistent with the existence of limit-order traders in liquidity provision. Besides, most traders tend to buy rather than sell stocks around the market close; on the contrary, day traders tend to sell rather than buy near the close. Hence, we may conclude that day traders are the main liquidity providers in the market.

Keywords: Order driven market, Limit order,

Market order, Liquidity provider

二、緣由與目的

Many securities markets are

organized as order-driven. The main stock markets including NASDAQ and LSE have incorporated order-driven systems in their market designs. Empirical evidences of introducing limit orders into the two quote-driven markets reveal that the trading costs are reduced in these markets. Even, in a quote-driven market such as the NYSE, limit orders compose of 45% of the total orders. The general focuses of the past studies are the roles of limit and market orders, the effects of limit orders in the market, the performance of limit order trading and the limit order execution time. (Glosten (1989, 1994), Easley and O’Hara

(1991), Angel (1994), Seppi(1997),

Sandas (1999)). Most of them are theoretical models; none of these studies provide an empirical investigation about who provides the liquidity in an order-driven market.

In a dealer market, dealers provide liquidity in the market by charging bid-ask spreads. Thus, bid-ask spreads are the trading costs for investors who demand for immediacy. Investors can choose to either post limit orders (which execute only if a counter-party meets the limit price) or submit market orders (which execute at the best available price). Investors who demand for immediacy may place market orders; however, market orders may be subject to price risk. On the contrary, the basic advantage of a limit order is the absence of price risk; however, limit orders may face a risk of non-execution.

In an order-driven market, buyers and sellers submit either limit orders or market orders to the market. In such a system, public limit orders supply liquidity and provide depth to the market; however there is no obligation for any participant to submit

such orders. Hence, unlike in a

quote-driven market wherein dealers play the role of liquidity providers, it is not clear as to who provides liquidity in an order-driven market

Relevant studies in the past had focused mostly on a dealer-driven market. While there exist many theoretical papers that model the liquidity services provided by market makers, only few works address to the role of liquidity providers theoretically. Handa and Schwartz (1996) endogenize the hypothesized trading decisions by simulation and view the trading environment as an ecology wherein the supply of, and demand for, liquidity can be in natural balance. The implications of Foucault’s (1999) models are:(1) the proportion of limit orders in the order flow is positively related to volatility, (2) the ratio of filled limit orders to the number of submitted limit orders is negatively related to volatility, and (3) limit order traders react to an increase in execution risk by posting larger spreads. At that time, traders are under pressure to place market orders to cope with the increase in execution

risk.

Empirical researches on the relevant issues are still nascent and it is not until recently that researchers started to focus on the limit order trading in an order-driven market. Harris and Hasbrouck (1996) examined the performance of limit orders and market orders using the TORA data. They found that limit orders may reduce execution costs. Lo, Mackinlay and Zhang (2001) provided an econometric analysis on limit order execution time, and found that execution times are very sensitive to limit price. Studies by Biais, Hillion and Spatt (1995) as well as Ahn, Bae and Chan (2000) examined the limit orders book using the best five quotes in the Paris Bourse market and the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, respectively. Biais, Hillion and Spatt (1995) found that traders adopted limit orders at times when spreads are wide and use more market orders at time when spreads are narrow. While, Ahn, Bae and Chan (2000) indicated that when transitory volatility arises from the ask (bid) side, investors will submit more limit sell(buy) orders than market sell(buy) orders, which is consistent with the existence of limit-order traders in liquidity provision.

Since Biais, et al. (1995) and Ahn, et al. (2000) used only best five quotes to address the role of limit orders, passive limit order trading strategies were ignored in their studies. Our study follows the lines of research on the role of limit orders in an order-driven market. By adopting all limit orders in the market; the study distinguishes active limit order trading from passive limit order trading. We classify all limit orders into seven levels in terms of aggressiveness to investigate who provides liquidity in an order-driven market. Besides, the rich dataset enables us to classify traders into

seven types, including professional

institutional traders (foreign traders, mutual fund managers and domestic competitive traders, domestic corporate investors), day traders (marginal day traders and pure day traders) and individual traders. In a dealer market, dealers play the role of supplying liquidity, however, it is unknown as to who provides liquidity in an order-driven market.

type, in our paper, may help to address the related issue, which is still ignored or unobserved in the past studies.

The purposes of our study are five-fold. First, we investigate the pattern of order placement for traders in an order-driven market. Second, this paper examines who are relatively less aggressive in entering the orders. It is likely that less aggressive orders provide liquidity to the market. Third, we analyze how traders react to price movement and transitory volatility. And thereby, the results may provide some evidence about whether traders who place orders less aggressively may play the roles of liquidity providers. Fourth, our study may shed some light on how the endogenously determined supply of liquidity works in an order-driven market. The result will help us to understand why aggressive limit orders, marketable orders and passive limit orders can be in natural balance. Fifth, by analyzing different firm size groups, we study who provides liquidity in the thin issue.

This study proposes the hypotheses as

follows. Institutional traders are

sophisticated investors; they have more knowledge and skills collecting information. Professional institutional investors may demand for liquidity in order to obtain

immediate execution of their orders.

Domestic professional corporations consist of listed companies, local banks, financial

securities firms and other financial

institutions. Domestic professional

corporations usually provide information to the public and to the institutional investors. It is plausible that some of information provided to institutional investors may contain private information. When all of the institutional investors mentioned above trade based on private information, they may desire for immediacy of execution to prevent revelation of private information. Since small firms may contain more private information, institutional investors may place aggressive orders in entering thin issues . Besides, since their positions are relatively large, they may demand for liquidity in order to shift their inventory risk. Accordingly, we may predict that institutional traders demand for market liquidity. However,

since institutional traders usually hold large positions, they tend to place orders less aggresive1y so as to reduce execution costs. In addition, institutional traders are more sophisticated in order placement; they have more skills in reducing the price impact. Hence, there is no prior prediction about whether institutional traders provide liquidity to the market..

Conventional wisdom characterizes day traders as speculative investors. Since some institutional traders are prohibited from day trade with margin, most of the day trades

were made by individual traders.

Attempting to buy and sell at the same day to capture stocks with temporarily volatility, they are forced to buy and sell passively to cover the large transaction costs incurred. Since day traders are well-known as speculators and contribute 25% of the trading volume in the Taiwan stock market, it is important to analyze whether they provide liquidity to the market. However, day traders may demand for market immediacy near the close to clear out their position, so as to reduce inventory risk.

Individual traders play an

important role in the Taiwan stock market, whose trades comprise around 55% of the total trading volume. Since the number of public investors has increased rapidly in the US market in recent years, an investigation of the ordering strategies of individual traders may shed some light on the market

behaviors. Lakonishok, Shleifer and

Vishny (1994) hypothesized that naive investors tend to be overoptimistic about the future prospects of stocks. Odean(1999) found that overconfident traders tend to trade too frequently. The Taiwan stock market is well-known for having the highest turnover rate of all the stock markets worlwide. It is important for us to examine whether individual traders are frequent traders. Since individual traders are more uncertain about the transaction prices than institutional traders, we propose that individual traders may place relatively conservative orders.

In sum, we examine who are the liquidity providers and shed some light on the plausible motivations of traders to place aggressive (passive) orders. Our ex ante

expectation is that professional institutional traders may demand liquidity in an order-driven market. On the other hand, while day traders and small traders provide market liquidity. However, since day traders are under pressure to clear their positions, they may demand for market immediacy near the close. The paper is organized as follows: section 2 describes the sample, data and institutional environment. Section 3 presents the definitions and empirical models. Sections 4 reports the empirical results and Section 5 concludes. 三、結果與討論

I. Sample and Data A. Sample

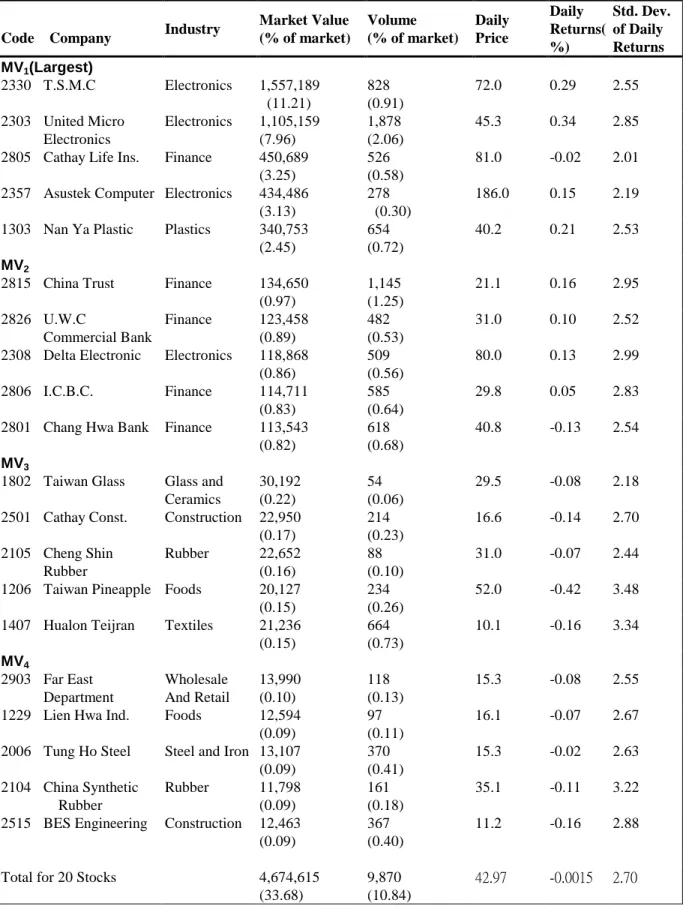

The sample period is from August 1998 to July 1999. Our sample period covered a bear market during the period from August 1998 to February 1999 (due to Asian Financial Crisis and a bull market from March 1999 to July 1999. This study selected sample from the Morgan Staley composite indices. Seventy-seven stocks are included in the Morgan Staley Investment company’s international market indices; these firms comprise over 60% of the market value and about 40% of the trading volume in the Taiwan stock market. We dropped two stocks because they were not listed before the sample period. Another three stocks were excluded from our sample because these issues had been reclassified into another industry groups. We divided the remaining 72 stocks into four groups based on their market values, and the five largest firms in each group were chosen. Table 1 is a summary of our sample. Our final sample consists of twenty stocks, which contribute to 37% of the total market value and 11% of the trading volume in the Taiwan stock market. Table 1 provides some descriptive statistics for the 20 sample firms. The sample represents 33.68% (10.84%) of the total market value (trading volume) of the Taiwan Stock Exchange. The average closing price is NT$43, the average daily return is –0.0015% and the standard deviation of daily returns is 2.7%.

[Insert Table 1 here]

B. Institutional Arrangements

We used orders that were submitted into the market to investigate the ordering strategies for investors. Trading days are from Mondays to Saturdays. Taiwan Stock Exchange is open for trades from 9 A.M. to 12 P.M.. The Taiwan Stock Exchange adopts an order-driven system without any designated market makers. Orders are automatically matched by the Computer

Automated Trading System (CATS).

Orders can be submitted before open between 8:30 A.M. to 9:00 A.M.. The Taiwan Stock Exchange adopts call markets, which are matched 1-2 times every 60 seconds throughout the trading day. Orders are only valid for a trading day.

There is a daily price limit of seven percent in each direction in the Taiwan Stock Exchange. Except for the opening price, which is allowed to change up to seven percent from the previous day’s closing price, there is a trade-by-trade intraday price limit of two ticks from the previous trade price. Although official market orders are not permitted, traders can submit an aggressive daily price-limit order or marketable order to obtain matching priority. This practice can achieve an equivalent effect of market orders. Thus, traders can submit an aggressive price-limit order to increase the probability of it being executed and yet have some price protection from intraday price limits. The price-limit orders have a greater impact on transaction price and trading volume than market orders. Short selling and margin trading are allowed for all stocks, except for those firms in financial difficulty. However, no institutional investors are allowed to sell short.

C. Data

We employed order-level data and

transaction-level data in this study. The order-level data include the date and time of order, the stock code, the order number, the type of order (buy or sell), the order price, the number of shares ordered, the brokerage code, and the account number of the buyer or seller. The transaction-level data include the date and time of the transaction, the stock

code, the order number, the type of order, the transaction price, the number of shares transacted, the brokerage code, and the account number of the buyer or seller.

We relied on the special account number assigned by the Taiwan Stock Exchange for each institutional investor to identify each money manager. There are three types of institutional investors in Taiwan. Domestic competitive traders (DCTs) are domestic institutional investors who can trade only against their own accounts. Qualified foreign institutional investors (QFIIs) are foreign institutional investors who are allowed to trade against their own accounts only. Mutual fund companies (MFs) are domestic mutual fund companies that invest for their clients. DCTs and QFIIs are equivalent to the proprietary traders in the U.S. The proportion of trading contributed by institutional investors is less than 10%. For details, please see Lee, Liu and Wei (2000).

Day traders are traders who buy and sell the same stock within the same day. Day traders must use margin trading (day traders with margin; hereafter MDT) in the Taiwan stock market; otherwise, they must have holdings for the target stocks they want to trade (day traders without margin; hereafter PDT). The Taiwan stock market has the highest turnover rate among the world’s stock markets; the value from 1996 onwards is around 300. Hence, a study as to whether frequent traders earn money and how they place their orders is warranted. We counted the trading frequency for each person for each stock during the sample period and used order frequency as control variable. Since individual traders contribute to the trading volume a lot, we also measured the order size in lots to control the order size strategies by investors.

By going through each account, we constructed the trading records for each date for an issue according to the sale date and price. Since the data was constructed from the total electronic data set from the Taiwan stock exchange, it is unlikely that selection bias will occur.

1. Data from the Taiwan stock Exchange

identify the origitor of each submitted order.

2. Since investors may have more than one

account in different brokerage houses, we aggregated all of the accounts that belonged to one single investor.

3. We adjusted for stock dividends and

cash dividends, where applicable. Stock dividends and cash dividends as well as other price data were obtained from the Taiwan Economic Journal database.

4. To avoid double counting due to trading

split, we aggregated the trade records that were initiated from the same order.

II. Empirical Models

We conducted the following multi-logistic models to examine the roles of different types of traders in the stock market. The dependent variable is the order type with a value ranging from 0 to 6, while the independent variables are dummy variables of the classifications of traders, including Insts (institutional traders) and DayTs(day traders). In the meantime, Inst,s DayTs and Indivs are set as (1,0), (0,1) and (0,0), respectively. We multiply Size, Freq and CloseT for each placement for the three types of traders in (1B), (1C) and (1D), respectively. While, Freq is the order frequency for each trader; size is the volume in lots for each trade; both of the values are in log form. CloseT is the time interval from 11:30 to12:00.

Price = b1Insts + b2DayTs +b3Size + b4Freq +b5CloseT + e (1A) Price = b1Insts*Size + b2DayTs*Size +b3Size +b4Freq +b5CloseT + e (1B)

Price = b1Insts*Freq + b2Days*Freq

+b3Size +b4Freq +b5CloseT + e (1C)

Price = b1Insts*CloseT + b2DayTs*CloseT +b3Size +b4Freq +b5CloseT + e (1D) We classified seven order types by the order

price; let P denote order price, CP represent previous closing price and PP is prevailing price, thus:

1. P0 is a market order; that is, order price

is at the upper (lower) limit for buy (sell) orders, i.e., P = 107% (93%) * CP for buy (sell) orders.

2. P1 is an aggressive marketable order;

order price is 3.5% above (below) the prevailing price, but below upper (lower) limit for buy (sell) orders, i.e., 103.5%*PP =< P < 107%*CP (93%*CP < P <= 96.5%*PP) for buy (sell) orders.

3. P2 is a marketable order; order price is above (below) the prevailing price, but is not higher (lower) than 3.5% above (below) the prevailing price for buy (sell) orders, i.e., PP < P < 103.5%*PP (PP > P > 96.5%*PP) for buy (sell) orders.

4. P3 is an order with the prevailing prices;

meaning that order price is equal to the prevailing price (zero tick) for both buy and sell orders, i.e., P=PP. P3 orders are similar to the prevailing orders.

5. P4 is a non-marketable order; order

price is lesser (greater) than 0 tick and higher (lower) than 3.5% below (above) the prevailing price for buy (sell) orders, i.e., PP>P>96.5%*PP (PP<P<103.5%*PP) for buy (sell) orders.

6. P5 is an order with price away from the

prevailing prices; order price is lower (higher) than 3.5% below (above) the prevailing price and higher (lower) than lower (upper) limit for buy (sell) orders, 96.5%*PP => P > 93%*CP (107%*CP>P>=103.5%*PP) for buy (sell) orders.

7. P6 is the most passive order; order price

is at the lower (upper) limit for buy (sell) orders; i.e., P=93%*CP (P=107%*CP) for buy (sell) orders.

To capture the ordering strategies of different types of institutional traders, day traders, individual traders, and orders entered in different intervals of time, we re-ran Equations (1A) to (1D) into Equaitons (2A) to (2D).

Price =b1QFIIs +b2MFs+b3DCTs +b4Corp +b5MDTs +b6PDTs+ b7Freq+b8Size +b9CloseT + e (2A) Price =Freq*[b1QFII s+b2MFs+b3DCTs +b4Corps +b5MDTs +b6PDTs] +b7Freq+b8Size +b9CloseT + e (2B) Price =Size*[b1QFIIs +b2MFs+b3DCTs +b4Corps +b5MDTs +b6PDTs] + b7Freq+b8Size +b9CloseT + e (2C) Price =CloseT*[b1QFIIs +b2MFs+b3DCTs +b4Corps +b5MDTs +b6PDTs] + b7Freq+b8Size +b9CloseT + e (2D)

For independent variables,

Insts Dummy variables of instituional traders including QFIIs, MFs, DCTs and Corps investors;

DayTs Dummy variable of

MDTs(margin day traders) and PDTs( pure day traders);

Freq Order frequency per trader; Size Order size per order; CloseT Time interval (11:30-12:00=1; otherwise=0)

To address the question as to who provides liquidity to the market, we measured the price movements, price reversals (price continuations), and the stock volatility. Typically, a liquidity provider (supplier) enters passive (aggressive) sell orders when price rises. While, Rt is the intraday return of five-minute intervals, we calculated the Rt for one trading day from the period of time T on date t to the time T on the previous date t-1. In total, thirty-one Rt were calculated. Ret c-T is the interday return measured by the log form of previous closing

price (Pt-1,c) divided by prevailing

transaciton price (Pt, T). Cor(Rt) and

STD(Rt) represent the correlation of

five-minute returns and standard deviation of five-minute returns, respectively. The dependent variables are seven types of order prices for each type of investors.

We ran logisitc models for seven types of investors in Equations (3A-1) to (3A-7), respectively for buys, and (3B-1) to (3B-7) for sells. Equations (3C-1) to (3C-7) test whether traders adopt buy or sell decisions

when the market conditions changes as mentioned above. Size and Freq capture the trading behaviors for each type of investors on their ordering strateigies. If the coefficients of buys ( b1, b2, b3 ) from a particular trader are negative, it means that traders tend to enter orders aggressively when the stock price falls, price is on a reversal, or volatility is large. Such kinds of strategies are likely to provide liquidity to the market. Trader b = a +b1 Rt c-T + b2Cor(Rt)+ b3STD(Rt)+ b4Size + b5Freq +e (3A) Trader s = a +b1 Rt c-T + b2Cor(Rt)+ b3STD(Rt)+ b4Size + b5Freq +e (3B) Trader = a +b1 R c-T + b2Cor(Rt)+ b3STD(Rt)+ b4 Size + b5Freq +e (3C)

III. Preliminary Results

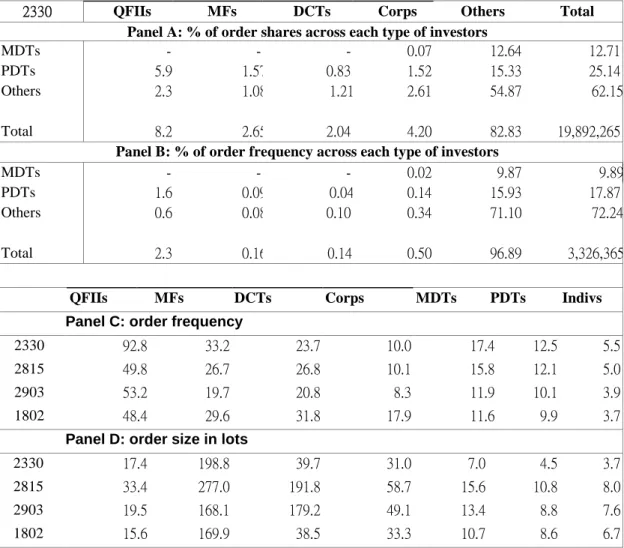

Our sample contains institutional traders, day traders and individual investors. Table 2 is the classification of investors. The findings can be presented both by each type of order and also by each kind of trader; however, since the results are similar, to save space, this study only shows the results made by each type of trader. First, we retrieved institutional trades, including QFII, MF, DCT and Corp from total sample. Second, we identified day traders, including MDT and PDT, from whole sample excluding institutional traders. Individuals are the traders from the sample that were not classified as institutional traders and day traders. In Panel A (B) of Table 2, the values in the cells are the percentages of total order shares (order frequency) of a particular type of trader relative to those of the total sample. Meanwhile, the values in the last column of the last row are the total order shares and total order frequency for all buys and sells, respectively, for Panels A and B. This study averages the values of each cell across each firm size group.

[Insert Table 2]

From Panel A of Table 2, we find that, in total, there were 19.89million, 16.39 million, 1.75 million and 1.02 million orders in lots during one year for MV1(2330), MV2, (2815), MV3 (2903) and MV4 (1802) stock. In terms of orders in lots (order frequency), institutional trades account for 12% to 22% (2% to 7%) of total orders. In the meantime, QFIIs and Corps tend to be relatively active in the market. MDTs for QFIIs, MFs and DCTs are not allowed to trade with margin within one trading day; accordingly, there is no such trade for them. For individual traders, around 13% to 15% (9% to 10%) of total orders in lots (frequency) were made by MDTs. In total, 25% of trades placed by others were day trading (PDTs and MDTs). Likewise, 50% to 60% ( 70% to 75%) of total orders in lots (frequency) were placed by other traders without day trading.

Since, in Panel A of Table 2, we find that only a few day trades are contributed by the institutional traders, we, then, identified day traders directly from the sample that excluded institutional traders in Panel B of Table 2. The remaining sample that excludes institutional traders and day traders is defined as the individual traders. This study documents trading behaviors including order frequency across each trader and size per order across each trader among seven types of traders and four groups of firm size in Panels C and D of Table 2. Results indicate that institutional traders seem to trade frequently, in particular for QFIIs. Individual traders trade less frequently than the other traders; the frequency is 4 to 5 times per year. Therefore, institutional traders rather than day traders and individual traders are frequent traders. A plausible reason for high order frequency for institutional traders is to spread their large orders to smaller ones. This phenomenon is particularly obvious for QFIIs. The order size made by institutional traders is larger than those by individual traders and day traders. Among institutional traders, MFs place orders in relatively large sizes (168-277 lots), while QFIIs enter their orders in

Individual traders place small orders; their order sizes, in general, are less than 10 lots. We got similar results for order size averaged across all orders for four stocks.

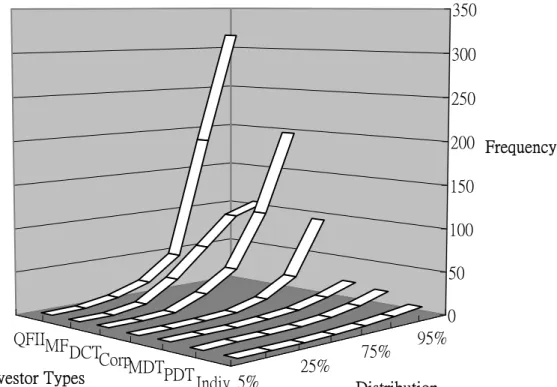

Figures 1A and 1B are the distributions of order frequency and order size in lots among types of traders. This paper averaged the order frequency and order size across each investor type. As we can see from Figure 1A, the order frequency is large for institutional traders from the top of the 75% of the traders, in particular for QFIIs. 25% of the institutional traders trade the stocks quite actively. The distributions of frequency are relatively flat for MDTs, PDTs and Indivs, which mean that only a small part of day traders and individual investors actively enter the market. In other words, day traders and individual traders enter the market less frequently.

[Insert Figure 1A here] [Insert Figure 1B here]

Figure 1B shows that 50% of institutional traders place large orders. Relatively speaking, MDTs, PDTs and Indiv place small orders; only 5% from the top enter large orders. Among them, the orders are relatively large for MDTs for 10% from the top traders. It is particularly interesting for us to examine whether the traders with large order sizes behave differently from the others and whether their trades contain some information.

We illustrated the ordering strategies across different intraday periods in Figure2. The trading time for one trading day is three hours (from 9:00 A.M. to 12:00 A.M.) in the Taiwan stock market. Before the 9:00 A.M. start, traders can enter their orders starting from 8:30 A.M. No execution is made and no market information is revealed before market open. Intraday periods are from T0 to T6; there are thirty minutes for each intraday period. We classified the orders into seven kinds of order types using the prevailing transaction price as the benchmark price. Different kinds of order types represent different extents of investors’ aggressiveness. Meanwhile, P0 is an

equivalent market order, P1 is an aggressive marketable order, P2 is a marketable order, P3 is an order wherein the order price is equal to the prevailing price, P4 is a non-marketable order, P5 is an order with price away from the prevailing prices, P6 is the most passive order.

The values in the Figures 2 and 3 are the percentages of frequency among seven types of ordering strategies for different intraday periods. Since the results are similar for four groups of stocks, we present the results for one typical stock. Figure 2 shows that investors tend to place conservative orders (P4 and P5) before market open. During the intraday period, most of the orders were placed at P0, P2, P3 and P4; in particular, for P0 and P4. This implies that investors tend to place equivalent market orders to have their orders executed immediately, or they may choose to enter limit orders waiting for some possible executions. Around market close, the percentage of orders placed at P0 is the highest compared to the other intraday periods; around 40% - 50% of the orders were clustered at upper limit for the buy side; on the contrary, the ratio is quite low before market open. This implies that investors buy orders in a relatively more aggressive manner near the market close.

[Insert Figure 2 here]

Our data allows us to identify the trades made by institutional traders, day traders and individual traders. Figure 3 presents the activities of the various trader types across seven intraday periods. The values in this Figure are the percentages of frequency among different types of investors that trade in different periods. The results indicate that the patterns of order frequency are roughly U-shaped for DCTs, Corps, MDTs, PDTs and Indivs except before market open

(T0). QFIIs place orders quite

conservatively before market open, yet they enter orders gradually during the intraday period, and they place orders aggressively around market close. The low placements before the market was opened may be due to the invisible information revealed before the opening of Taiwan’s market. For the other

type of trader, the percentage of orders is clustered at the open (9:000-9:30). Besides, it seems that QFIIs demand for liquidity at market close.

[Insert Figure 3]

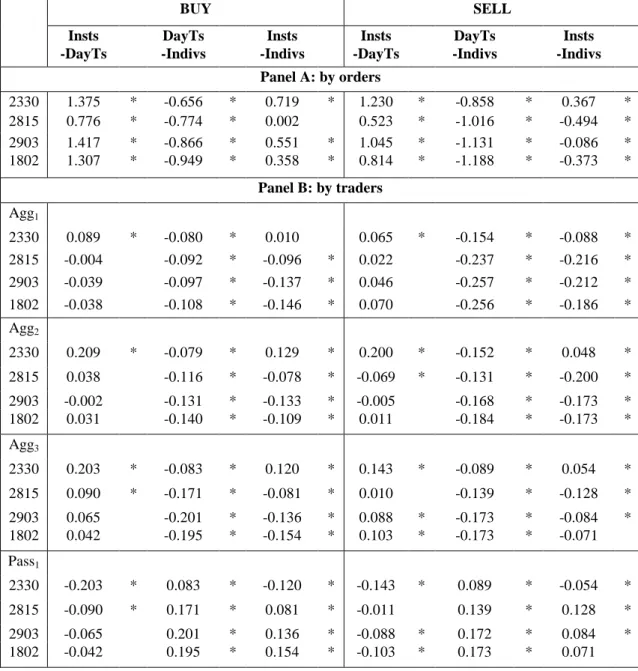

We classified the orders into seven kinds of order types using the prevailing transaction price as the benchmark price. Different kinds of order types represent different extents of investors’ aggressiveness. In Panel A of Table 3, this study sets P0, P1, P2, P3 P4, P5 and P6 to equal to1,2,3,4,5,6 and 7, respectively. The Scheffe’s test was adopted to compare the difference between aggressiveness of each type of order placed by investors in Table 3.

[Insert Table 3]

The values in Table 3 are the mean differences between the aggressiveness of Insts vs. DayTs, DayTs vs. Indivs and Insts vs. Indivs. From Panel A, we find that, in terms of orders, the values are positive for Insts vs. DayTs; this means that the aggressiveness of Inst is greater than that of DayTs. Likewise, the finding reveals that DayTs is less aggressive than Indivs and Inst trade more actively than Indivs for the buy side. That is to say, institutional traders are the most aggressive ones, while day traders are the most passive ones among three types of traders for the buy side. As for the sell side, individual traders are the most aggressive group of traders, while day traders are the most passive type of traders. The finding implies that institutional traders seem to be more patient in selling their holdings; they may sell stocks when prices rise

We measured the aggressiveness of each trader type by finding the ratio of frequency in each classification of prices (P0, P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6) relative to total frequency (TF)for each investor for each type of trader in Panel B. And then, we summarized the results by the ratios for each trader across each type of investor, defined as

(Agg1=P0,/TF, Agg2=(P0+ P1+P2))/TF,

Agg3=(P0+P1+P2+P3 )/TF,

Pass1=(P4+P5+P6) /TF, and Pass2= (P6)/TF.

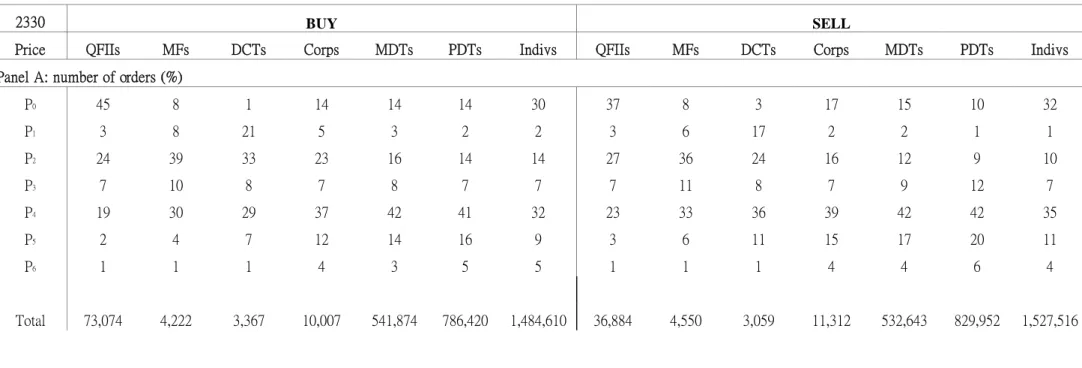

The Scheffe’s test was adopted to compare the difference between aggressiveness of each type of investor in Table 3. Results from Table 3, Panel B, are similar to those from Panel A in Table 3. In general, the difference between Insts and DayTs are positive (negative) for Agg1, Agg2 and Agg3 (Pass1 and Pass2), which imply that institutional traders are more aggressive than day traders. Likewise, DayTs is more passive than Indivs, and Inst is more aggressive than Indivs; however, the latter only exists for the large firm group(2330). Therefore, the findings are consistent for the buys and sells in Panels A and B, irrespective of when the size of aggressiveness or the probabilities of aggressiveness is applied. Following Table 3, Table 4 presents a detailed summary of the percentages of numbers by orders and investors for each order type. The values in the cells are the percentages of order frequencies averaged across each type of order. To save space, we present only the results for 2330 here; for the other issues, please see the Appendix. Results indicate that, in terms of number of orders, QFIIs are the most aggressive traders. For the buy side, the ratio of placing at P0 is the highest for QFIIs among seven types of traders; the number is 45%, 53%, 61% and 75%, respectively, for 2330 (the largest firm size), 2815, 2903 and 1802 (the smallest firm size). For details, please see the Appendix. The clustering of aggressive orders for QFIIs are relatively obvious for thin issues (2903 and 1802) and for the buy side. This implies that QFIIs are aggressive in buying issues, particularly for thin issues. Since thin issues may contain more asymmetric information, it is likely that QFIIs trade thin issues aggressively because they may have some privilege of private information than individual traders. Orders from the other institutional traders (MFs, DCTs and Corps) are partially located around P2. Though there are some trading limitations for MFs and DCTs to place at P0, we still find that the summations of P0 and P1 are less than those of QFIIs at P3 and P4. Orders placed at P1, P2 and P3 are more likely to be executed than those placed at P4, P5 and P6, implying that institutional orders are relatively

aggressive ones. [Insert Table 4]

The ratio of the most aggressive orders for individual traders is the second largest one among seven types of traders; 30%, 39%, 28% and 27%, in that order, from the largest firm size to the smallest firm size for the buy side. The pattern is similar for the sell side. It is an interesting question for us to study why individual traders also place orders aggressively. Day traders (MDTs and PDTs) place orders quite passively; among all of the stocks, the ratio at P5 for day traders is around 40% to 60%. The ratio at P6 and P7 is also larger for day traders than the other types of traders. It is plausible that day traders have to buy at low prices and sell at high prices to capture one-day volatility.

Since one trader may place more than once during the same period, we also calculated the number of traders for each level of pricing strategy to reduce the impact of trading frequency. In terms of number of traders, the percentage of P0 is 22%, 25%, 24% and 24%, in that order, for QFIIs’ buys. As can be seen, the numbers mentioned above are smaller than those calculated by number of orders in lots. On the overall, institutional traders place orders aggressively; QFIIs are the most aggressive in entering orders and MFs, DCTs and Corps are relatively less aggressive. The percentages of P0 for individual traders are also large among four firm size groups. It is an interesting question to study why individual traders demand for market immediacy. It seems that the ratios are the largest at P5 for day traders compared to the other price levels, which implies that day traders are less aggressive investors. Yet, we also find that the ratios of P0 for day traders are relatively large than those of MFs, DCTs and Corps. It is plausible that day traders may demand for liquidity due to the limitation of one trading day, and day traders may have strong desires for market immediacy near the close. In the next section, we will examine whether the orders placed at P0 for day traders are mainly from the closing period.

In general, investors place buys more aggressively than sells. Regardless of the type of trader, traders concentrated on the limit prices of P0, P2, P3 and P4. That is, prices clustered on the upper (lower) price limits for buys (sells), the marketable prices, the prevailing prices and the prices ranged between the prevailing prices and 3.5% below the prevailing prices.

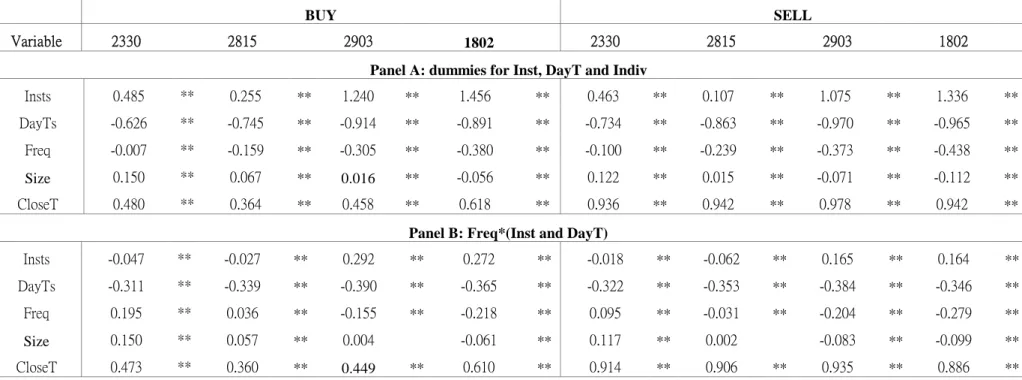

Table 5 presents the results using logistic models. Dependent variable of the model is the order type classified by the

seven levels of order price. For

independent variables, Insts, DayTs and Indivs are the classification for each type of order price for each investor. CloseT is a dummy variable, in which orders placed during 11:30 to 12:00 equal to 1, otherwise 0. Freq and Size are the order frequency and order size per trade, respectively, for each

trader; they are continuous variables

measured in log form. MV1(2330), MV2(2815), MV3 (2903) and MV4(1802) are the classifications of firm size groups from the largest group to the smallest one. Panel A of Table 5 looks at the ordering strategies using dummies for each type of trader, while Panels B to D consider the interaction of traders’ types (Insts, DayTs and Indivs) and trading behaviors (Freq, Size and CloseT). The results indicate that all of the coefficients of Insts are positive among four groups of stocks in Panel A, implying that the Insts are more aggressive than Indivs. The negative (positive) coefficients of Inst in Panel B for large firms (2330 and 2815) means that the more frequently the Insts place an order, the more passive (aggressive) the Insts rather than Indivs are. This may be due to the stealth trading strategies of institutional traders for large firms. That is, institutional traders may tend to spread their orders into small ones; accordingly, they enter the market frequently and passively. Similarly, the positive coefficients of Insts in Panel C imply that the larger the order size placed by the institutional traders, the more passive (aggressive) the institutional traders would place rather than those from Indivs traders for large (small) firms. Panel D reveals that Insts, in general, will act more aggressively than Indivs when they enter the

orders near the market close.

The coefficients of DayTs are negative except for the sell side in Panel D; this indicates that day traders tend to be more passive than individual traders, particularly when they trade frequently or place large orders. However, it is interesting to find, in Panel D, that day traders sell their orders more aggressively than those placed by individual traders near market close. It is likely that day traders desire to liquidate their inventories near the market close. This may support the hypothesis that day traders, in general, provide liquidity to the market; however, they demand for market liquidity near the close. In sum, we find that institutional traders are liquidity demanders, in particular when they enter the market near the close. In addition, we find that Insts tend to be more passive than Indivs when they place large orders or trade frequently in large issues. The plausible reason for institutional traders to do so is to trade stealthily to reduce their price impacts on the market. Day traders are likely to provide liquidity to the market; however, they desire for market immediacy near the close.

Freq is negatively related with

aggressiveness of orders; this reveals that frequent traders place orders passively. Since Odean (1999) found that overconfident traders tend to trade frequently using the sample from the individual traders, we will examine, in Table 7, whether individual traders who trade frequently will place orders aggressively. A future study may focus on whether frequent traders are unprofitable to support the results by Odean(1999). Since we find that Insts trade more frequently than DayTs and Indivs, such behavior is possible due to the need of spreading large orders into smaller ones instead of overconfidence. Generally, Size has a positive sign in most cases, which implies that the larger the order size placed by traders, the more aggressively the trader may act. It implies that large order sizes may contain some information, and thus induces traders to demand for immediate execution of their orders. The coefficients of CloseT are positive, which may imply that traders tend

to place aggressive orders to have their orders executed immediately near market close.

[Insert Table 5 Here]

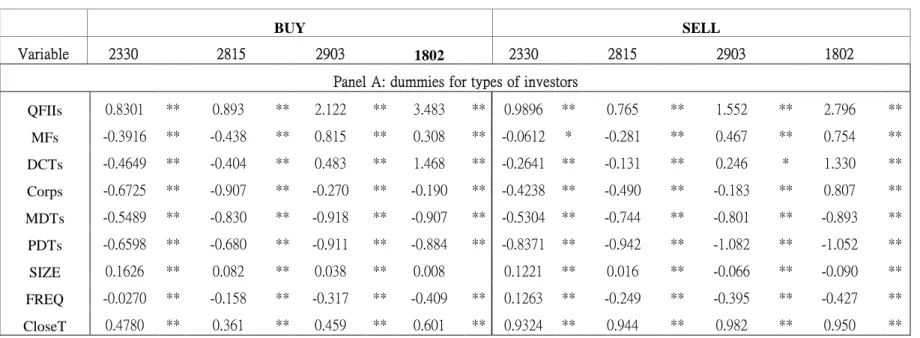

Table 6 classifies the traders into QFIIs, MFs, DCTs, Corps, MDTs, PDTs and Indivs. As shown in Table 6, the coefficients of QFIIs are all positive among four stocks, which implies that QFIIs are more aggressive than individual traders. Most of the coefficients of the other institutional traders (MFs, DCTs and Corps) are positive for small firm size groups (2903 and 1802), while those for large firms (2330 and 2815) are negative. This means that institutional traders are more aggressive than individual traders for small firms, yet more passive than individual traders for large firms. This phenomenon is similar to those in Panels B, C and D. That is, when the QFIIs for all issues and MFs and DCTs for small firms place orders more frequently, with larger order sizes or near the close, they will be more aggressive than the individual traders. It seems that firm size affects the ordering strategies of institutional traders or individual traders. We conjecture that due to information asymmetry in small firms, individual traders may enter orders more cautiously for small firms; on the contrary, institutional traders may have the privilege of information for thin issues and thus they may act aggressively on thin issues. These results indirectly support for information hypothesis.

When the aggressiveness levels of

institutional traders are compared, we find that QFII is the most aggressive type of trader, while Corp is the most passive type of trader. One possible reason is that QFIIs are more informed since they are global investors and have more profound analyses. While, Corps are not professional financial institutions in the market; hence, they may be more be cautious in trading, or they may be a long-term investors.

We find that all of the coefficients of MDTs and PDTs are negative, which indicate that day traders are generally more passive than individual traders. This result is consistent

with what we have found in Table 5 no matter when frequency, order size or close time is considered. Comparing the aggressiveness levels of MDTs and PDTs, it is quite interesting to find that MDTs tend to be more passive than PDTs for buys and more aggressive than PDTs for sells. Most of the MDTs place buys and then sells within the same trading day because it is inconvenient for day traders to sell short during one trading day in the Taiwan stock market. Since MDTs have to close out their positions during one trading day, MDTs may enter buy orders cautiously; and when they sell their inventories, they may tend to be aggressive to liquidate their positions. In general, the coefficients of Size are positive, those of Freq are negative, and those of CloseT are positive, which is consistent with those of Table 5.

[Insert Table 6 Here]

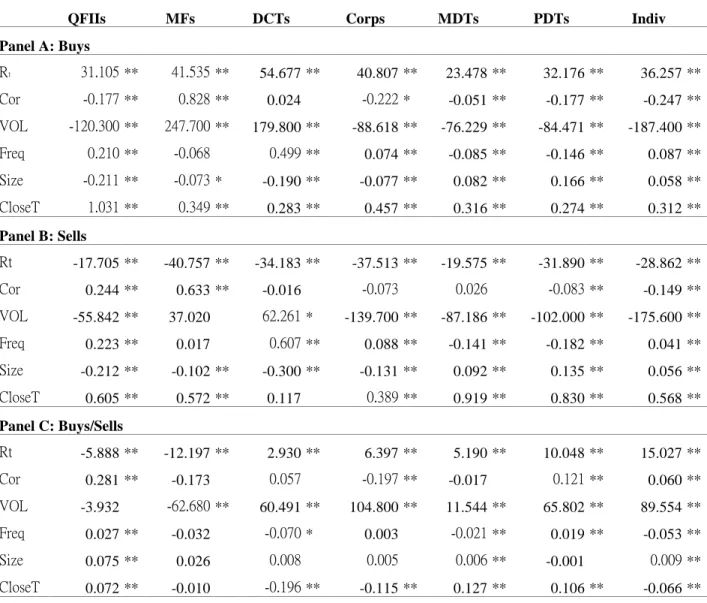

Table 7 studies how each type of trader makes buy and sell ordering decisions when the price rises or falls temporarily, prices reverse or continue and when the interday stock volatility is widened or shorten. Typically, a liquidity provider (supplier) enters passive (aggressive) sell orders when prices rise. Accordingly, if the coefficients of intraday returns (Rt), the correlations of Rt and the interday volatility (Vol) are negative, then that particular type of trader is a liquidity provider.

[Insert Table 7 Here]

Table 7 investigates the ordering strategies

contingent upon temporarily market

movements, price reversals and stock volatility for seven types of traders. In Panel A, the results indicate that the coefficients of Rt are positive for buys, implying that traders buy aggressively when prices rise. Among seven types of traders, MFs and QFIIs are the relatively more aggressive ones, while MDTs are the most passive ones. The coefficients of Rt in Panel B are negative, indicating that most of the traders tend to sell orders aggressively (passively) when prices fall (rise). In the meantime, QFIIs are the most aggressive

ones to sell orders when prices rise, while MFs and DCTs are relatively more passive ones. The results seem to imply that most investors are trend chasers in a short run for both buys and sells; investors buy at high prices when the market is upward, and sell at low prices when the market is downward. Regarding the buy and sell decisions, we set buys equal to one, and sells equal to zero. The logistic models of the buy and sell decisions are shown in Panel C. The results indicate that the coefficients of Rt for QFIIs and MFs are negative, while those for DCTs and Corps are positive. This means that when prices rise, QFIIs and MFs tend to buy stocks; on the contrary, they tend to sell stocks when prices fall. Day traders and individual traders may sell stocks when prices rise, and buy stocks when prices fall. This finding provides another evidence to show that professional institutional traders are basically liquidity demanders; they buy stocks when prices rise in a short time and they tend to place aggressively to buy stocks whose prices have risen for a short period of time. On the contrary, individual traders and day traders provide liquidity to the market.

As for the correlations of five-minute returns and interday price volatility, we find, in Panels A and B, that the coefficients of Cor(Rt) and STD(Rt) are positive for institutional traders, while those are negative for day traders and individual traders irregardless of when investors buy or sell. These evidences reveal that institutional traders enter their orders aggressively when there were price continuations, or when volatility was increased in a short run. On the contrary, individual traders and day traders place their orders passively once prices have continuations and/or volatility was large. However, the results shown in Panel C are not consistent among four stocks. Since day traders and individual traders submit more non-marketable limit orders than institutional traders in a volatile market, their behaviors seem to conform to the models by Foucault (1999). That is, the ordering strategies of day traders and individual traders show that an increase in

non-marketable limit orders. The placement of passive limit orders mitigates a large transitory volatility in an order-driven market. This is consistent with the existence of limit-order traders in liquidity provision.

As for the order frequency of a trader, we find that Freq, in Panels A and B, is positively related with the aggressiveness of orders for institutional traders and negatively related with the aggressiveness of orders for day traders and individual traders. Our results suggest that the higher the order frequency is, the more the aggressive institutional trader will be, while the less aggressive day traders and individual traders will be. The Freq in Panel C reveals that the coefficients of Freq are negative in most of the cases, implying that frequent traders tend to buy issues rather than sell stocks.

Size is negatively related with

aggressiveness of orders in most cases in Panels A and B. In Panel C, most of the coefficients of Size are positive, except for day traders. This result suggests that the larger the order size is, the more passive the trader will be for both buys and sells. Meanwhile, the larger the order size is, the higher the probability that a trader will placesell orders. CloseT is positively related with aggressiveness of orders in Panels A and B, while CloseT is negatively related with order aggressiveness, except for day traders. This means that traders tend to place orders aggressively near the close, while traders tend to buy stocks rather than sell stocks around the market close, except for day traders. It is interesting to find that day traders usually buy and then sell during the same trading day, while the other groups of traders tend to buy stocks around the close and sell them during the other intraday periods. Since there is a positive overnight return, and a negative intraday return in the Taiwan stock market, we conjecture that day traders are likely to be losers.

四、計畫成果自評

This study analyzes who provides liquidity in an order-driven market by

studying the buy and sell choices and ordering strategies for different types of investors. Basically, we find that investors tend to enter equivalent market orders to have their orders executed immediately, or they may wait for plausible executions of their orders by placing limit orders that are a little below the prevailing transaction prices. Concerning the buy/sell decisions, the results indicate that most investors are trend chasers in the short run for both buys and sells. Traders tend to buy more aggressively than sell. Professional institutional traders buy (sell) stocks when prices have risen (fallen) in a short time and they tend to place aggressively to buy stocks whose prices have risen for a short period of time. In general, QFIIs are the most aggressive traders. Vice versa for the individual traders and day traders.

In a volatile market, day traders and individual traders submit more non-marketable limit orders than institutional traders. The ordering strategies of day traders and individual traders show that less aggressive orders tend to provide liquidity to the market and may mitigate a large transitory volatility in an order-driven market. Therefore, the behaviors of day traders and individual traders are consistent with the existence of limit-order traders in liquidity provision.

We also documented that institutional traders, rather than day traders and individual traders, are the more frequent traders. One plausible reason for institutional traders to trade frequently is the need for stealth trading. Frequent traders usually place passive orders; however, the higher the order frequency is, the more aggressive the institutional trader will be, while the less aggressive the day traders and individual traders will be. It is an unsolved question as to whether institutional act aggressively because they have already reduced their order size by trading frequently, and/or because they tend to be overconfident.

Investors who place large order sizes enter their orders aggressively. This implies that traders with large size may contain some private information and thus

Institutional traders often place large orders. We found institutional traders place large orders passively (aggressively) for large (small) firms. The goal of the former may be to reduce price impact on the market, while that of the latter may be to capture immediacy of execution for trading on the advantage of inside information in a thin issue.

As for closure effects, traders tend to place orders aggressively near the close. In the meantime, institutional traders are more aggressive than individual traders near the close for buys and sells. Institutional traders own large positions and thereby may have strong desires to shift their risk before the end of the trading day. Day traders sell their holdings aggressively near the market close, implying that day traders are forced to liquidate their inventories near the close. Most traders tend to buy rather than sell stocks around the market close; on the contrary, day traders tend to sell rather than buy near the close. Since, in general, there is a positive overnight return, and a negative intraday return in the Taiwan stock market. We conjecture that day traders are likely to be losers.

In sum, this study supports the hypothesis that professional institutional traders including foreign traders, mutual fund managers, domestic competitive traders and domestic corporate investors demand for liquidity in an order-driven market. Institutional traders tend to act aggressively, placing large orders for thin issues or near the close to shift their risk or clear their positions. Yet, they enter large orders passively for think issues so as to reduce price impacts on the market. On the contrary, day traders place orders relative more passively; they are the liquidity providers in the market.

本計畫結果與預期相符合,應具有國 際期刊的發表機會,計畫成果對證券市場

結構有關流動性提供者的角色提出具體的 分析架構。

五、參考文獻

1. Ahn, Hee-Joon, Bae, Kee-Hong and Chan, Kalok, 2000, Limit Orders, Depth, and Volatility: Evidence from the Stock

Exchange of Hong Kong, The Journal of

Finance, Forthcoming 2000.

2. Al-Suhaibani, Mohammed and

Kryzanowski, Lawrence, 2000, An

Exploratory Analysis of the Order Book, and Order Flow and Execution on the Saudi Stock Market, Journal of Banking and Finance 24, 1323-1357.

3. Biais, Bruno, Hillion, Pierre and Spatt, Chester, 1995, An Empirical Analysis of the Limit Order Book and the Order Flow

in the Paris Bourse, The Journal of

Finance 50, Number 5, 1655-1689.

4. Brockman, Paul and Chung, Dennis Y., 1999, An Analysis of Depth Behavior in an Electronic Order-driven Environment,

Journal of Banking and Finance 23,

1861-1886.

5. Chung, Kee H., Van Ness, Bonnie F. and Van Ness, Robert A., 1999, Limit Orders and the Bid-ask Spread, Journal of Financial Economics 53, 255-287.

6. Cohen, K., S. Maier, R. Schwartz, D. Whitcomb, 1981, Transaction Costs, Order Placement Strategy, and Existence of the Bid-ask Spread,

Journal of Political Economy 89,

287-305.

7. Foucault, Thierry, 1999, Order Flow Composition and Trading Costs in a

of Financial Markets 2, 99-134.

8. Glosten, Lawrence, 1994, Is the Electronic Open Limit Order Book Inevitable ?

Journal of Finance 49, 1127-1161.

9. Handa, Puneet and Robert A. Schwartz,

1996, Limit Order Trading, The Journal

of Finance 51(5), December, 1835-1861.

10. Hanada, Puneet, Schwartz, Robert A. and Tiwari, Ashish, 1998, The Ecology of

an Order-driven Market, Journal of

Portfolio Management 24(2), 47-55.

11.Handa, Puneet, Schwartz, Robert A.and Tiwari, Ashish, 1999, Quote Setting and Price Formation in an Order Driven

Market, Working Paper.

12.Harris, L. and Joel Hasbrouck, 1996, Market versus Limit Orders: the

SuperDOT Evidence on Order

Submission Strategy, Journal of

Financial Quantitative Analysis 31(2),

213-231.

13.Hasbrouck, Joel and Seppi, Duane J., 1999, Common Factors in Prices, Order

Flows and Liquidity, Working Paper.

14.Kavajecz, Kenneth A. and Odders-White, Elizabeth R., 2000, Volatility, Market

Structure, and Information Flows,

Working Paper.

15.Lee Yi-Tsung, Liu Yu-Jane and K.C. John

Wei, 2001, Institutional Trading:

Execution Costs and Opportunity Costs,

Working Paper.

16.Lo, A. W., A Craig MacKinlay and J. Zhang, 2001, Econometric Models of Limit-Order Executions, The Review of

Financial Studies, Forthcoming 2001.

17.Seppi, Duane J., 1997, Liquidity

Provision with Limit Orders and a

Strategic Specialist, The Review of

Financial Studies 10(1), 103-150.

18.Odean, Terrance, 1999, Do Investors

Trader Too Much? American Economic

Table 1 Sample Descr iption

Market Value: million dollars

Trading Volume: million shares

Code Company Industr y

Mar ket Value (% of mar ket) Volume (% of mar ket) Daily Pr ice Daily Retur ns( % ) Std. Dev. of Daily Retur ns MV1(Largest) 2330 T.S.M.C Electronics 1,557,189 (11.21) 828 (0.91) 72.0 0.29 2.55 2303 United Micro Electronics Electronics 1,105,159 (7.96) 1,878 (2.06) 45.3 0.34 2.85 2805 Cathay Life Ins. Finance 450,689

(3.25)

526 (0.58)

81.0 -0.02 2.01 2357 Asustek Computer Electronics 434,486

(3.13)

278 (0.30)

186.0 0.15 2.19 1303 Nan Ya Plastic Plastics 340,753

(2.45)

654 (0.72)

40.2 0.21 2.53 MV2

2815 China Trust Finance 134,650 (0.97) 1,145 (1.25) 21.1 0.16 2.95 2826 U.W.C Commercial Bank Finance 123,458 (0.89) 482 (0.53) 31.0 0.10 2.52 2308 Delta Electronic Electronics 118,868

(0.86) 509 (0.56) 80.0 0.13 2.99 2806 I.C.B.C. Finance 114,711 (0.83) 585 (0.64) 29.8 0.05 2.83 2801 Chang Hwa Bank Finance 113,543

(0.82)

618 (0.68)

40.8 -0.13 2.54 MV3

1802 Taiwan Glass Glass and Ceramics 30,192 (0.22) 54 (0.06) 29.5 -0.08 2.18 2501 Cathay Const. Construction 22,950

(0.17) 214 (0.23) 16.6 -0.14 2.70 2105 Cheng Shin Rubber Rubber 22,652 (0.16) 88 (0.10) 31.0 -0.07 2.44 1206 Taiwan Pineapple Foods 20,127

(0.15)

234 (0.26)

52.0 -0.42 3.48 1407 Hualon Teijran Textiles 21,236

(0.15) 664 (0.73) 10.1 -0.16 3.34 MV4 2903 Far East Department Wholesale And Retail 13,990 (0.10) 118 (0.13) 15.3 -0.08 2.55 1229 Lien Hwa Ind. Foods 12,594

(0.09)

97 (0.11)

16.1 -0.07 2.67 2006 Tung Ho Steel Steel and Iron 13,107

(0.09) 370 (0.41) 15.3 -0.02 2.63 2104 China Synthetic Rubber Rubber 11,798 (0.09) 161 (0.18) 35.1 -0.11 3.22 2515 BES Engineering Construction 12,463

(0.09)

367 (0.40)

11.2 -0.16 2.88

Total for 20 Stocks 4,674,615 (33.68)

9,870 (10.84)

Table 2 Classifications of Investor s

We retrieved institutional trades, including QFIIs, MFs, DCTs and Corps. from the total sample. Second, we identified day traders, including MDTs and PDTs, from the whole sample. We did not exclude day traders from institutional traders. In Panels A and B, others are the traders that exclude the institutional traders. The values in the cells are the percentages of total order shares averaged across total sample (Panel A) and those of total order frequency (Panel B). Meanwhile, the values in the last column of the last row are the total order shares and total order frequency, respectively, for each panel. In Panels C and D, we present the order size and order frequency for each type of investors. Since only a few day trades were contributed by the institutional traders, we identified day traders, including MDTs and PDTs, from the individual sample. Thus, individuals (Indivs) are the traders that exclude the institutional traders and day traders. The values in the cells are the values averaged across each firm size group (MV1 to

MV4). 2330, 2815, 2903 and 1802 are the largest issues for each firm group.

2330 QFIIs MFs DCTs Cor ps Other s Total Panel A: % of or der shar es acr oss each type of investor s

MDTs - - - 0.07 12.64 12.71 PDTs 5.90 1.57 0.83 1.52 15.33 25.14 Others 2.38 1.08 1.21 2.61 54.87 62.15

Total 8.28 2.65 2.04 4.20 82.83 19,892,265 Panel B: % of or der fr equency acr oss each type of investor s

MDTs - - - 0.02 9.87 9.89 PDTs 1.68 0.09 0.04 0.14 15.93 17.87 Others 0.63 0.08 0.10 0.34 71.10 72.24

Total 2.31 0.16 0.14 0.50 96.89 3,326,365

QFIIs MFs DCTs Cor ps MDTs PDTs Indivs Panel C: order frequency

2330 92.8 33.2 23.7 10.0 17.4 12.5 5.5

2815 49.8 26.7 26.8 10.1 15.8 12.1 5.0

2903 53.2 19.7 20.8 8.3 11.9 10.1 3.9

1802 48.4 29.6 31.8 17.9 11.6 9.9 3.7

Panel D: order size in lots

2330 17.4 198.8 39.7 31.0 7.0 4.5 3.7

2815 33.4 277.0 191.8 58.7 15.6 10.8 8.0

2903 19.5 168.1 179.2 49.1 13.4 8.8 7.6

Table 3 Aggr essiveness for Types of Tr ader s: Scheffe’s Test

We classified the orders into seven kinds of order types using the prevailing transaction price as the benchmark price. Meanwhile, P0 is an equivalent market order, P1 is an aggressive marketable order, P2 is

a marketable order, P3 is an order in which the order price is equal to the prevailing price, P4 is a

non-marketable order, P5 is an order with price away from the prevailing prices, P6 is the most passive

order. In Panel A, this study sets P0, P1, P2, P3 P4, P5 and P6=1,2,3,4,5,6 and 7, respectively, by

classifications of each order for each type of traders. We measured the aggressiveness of each type of trader by finding the ratio of order frequency in each classification of prices (P0, P1, P2, P3, P4, P5, P6)

relative to total order frequency (TF) for each investor for each type of trader in Panel B. And then, we summarized the results by the ratios for each trader across each type of investors, defined as (Agg1=P0,/TF,

Agg2=(P0+ P1+P2))/TF, Agg3=(P0+P1+P2+P3 )/TF, Pass1=(P4+P5+P6)/TF, and Pass2= (P6)/TF. The

Scheffe’s test was adopted to compare the difference between aggressiveness of each type of investor in Table 3. BUY SELL Insts -DayTs DayTs -Indivs Insts -Indivs Insts -DayTs DayTs -Indivs Insts -Indivs Panel A: by or der s 2330 1.375 * -0.656 * 0.719 * 1.230 * -0.858 * 0.367 * 2815 0.776 * -0.774 * 0.002 0.523 * -1.016 * -0.494 * 2903 1.417 * -0.866 * 0.551 * 1.045 * -1.131 * -0.086 * 1802 1.307 * -0.949 * 0.358 * 0.814 * -1.188 * -0.373 * Panel B: by tr ader s Agg1 2330 0.089 * -0.080 * 0.010 0.065 * -0.154 * -0.088 * 2815 -0.004 -0.092 * -0.096 * 0.022 -0.237 * -0.216 * 2903 -0.039 -0.097 * -0.137 * 0.046 -0.257 * -0.212 * 1802 -0.038 -0.108 * -0.146 * 0.070 -0.256 * -0.186 * Agg2 2330 0.209 * -0.079 * 0.129 * 0.200 * -0.152 * 0.048 * 2815 0.038 -0.116 * -0.078 * -0.069 * -0.131 * -0.200 * 2903 -0.002 -0.131 * -0.133 * -0.005 -0.168 * -0.173 * 1802 0.031 -0.140 * -0.109 * 0.011 -0.184 * -0.173 * Agg3 2330 0.203 * -0.083 * 0.120 * 0.143 * -0.089 * 0.054 * 2815 0.090 * -0.171 * -0.081 * 0.010 -0.139 * -0.128 * 2903 0.065 -0.201 * -0.136 * 0.088 * -0.173 * -0.084 * 1802 0.042 -0.195 * -0.154 * 0.103 * -0.173 * -0.071 Pass1 2330 -0.203 * 0.083 * -0.120 * -0.143 * 0.089 * -0.054 * 2815 -0.090 * 0.171 * 0.081 * -0.011 0.139 * 0.128 * 2903 -0.065 0.201 * 0.136 * -0.088 * 0.172 * 0.084 * 1802 -0.042 0.195 * 0.154 * -0.103 * 0.173 * 0.071

Pass2

2330 -0.036 * -0.019 * -0.042 * -0.018 * 0.004 * -0.014 *

2815 -0.007 0.001 -0.006 -0.007 0.007 * 0.000

2903 -0.002 0.016 * 0.014 -0.008 0.013 * 0.006

Table 4 Classifications of Or der ing Str ategies

The first column of the table is the order type classified according to order price. While P0 is an equivalent market order; that is, the order price is at the upper (lower) limit

for buy (sell) orders. P1 is an aggressive marketable order; that is, the order price is 3.5% above (below) the prevailing price, but below the upper (lower) limit for buy (sell)

orders. P2 is a marketable order; that is, the order price is above (below) the prevailing price, but is not higher (lower) than 3.5% above (below) the prevailing price for buy

(sell) orders. P3 is an order in which the order price is equal to the prevailing price. P4 is a non-marketable order; that is, the order price is lesser (greater) than 0 tick and

higher (lower) than 3.5% below (above) the prevailing price for buy (sell) orders. P5 is an order with price away from the prevailing prices; that is, the order price is lower

(higher) than 3.5% below (above) the prevailing price and higher (lower) than lower (upper) limit for buy (sell) orders. P6 is the most passive order; that is, the order price

is at the lower (upper) limit for buy (sell) orders. The values in the cells are the percentages of order frequencies averaged across each stock. Meanwhile, the values in the last row are the total order frequencies for each type of trader.

2330 BUY SELL

Price QFIIs MFs DCTs Corps MDTs PDTs Indivs QFIIs MFs DCTs Corps MDTs PDTs Indivs Panel A: number of orders (%)

P0 45 8 1 14 14 14 30 37 8 3 17 15 10 32 P1 3 8 21 5 3 2 2 3 6 17 2 2 1 1 P2 24 39 33 23 16 14 14 27 36 24 16 12 9 10 P3 7 10 8 7 8 7 7 7 11 8 7 9 12 7 P4 19 30 29 37 42 41 32 23 33 36 39 42 42 35 P5 2 4 7 12 14 16 9 3 6 11 15 17 20 11 P6 1 1 1 4 3 5 5 1 1 1 4 4 6 4 Total 73,074 4,222 3,367 10,007 541,874 786,420 1,484,610 36,884 4,550 3,059 11,312 532,643 829,952 1,527,516