考試導向的學習情境下試題預覽學習單對提升國中生英語學習動機與學習成就之效益 - 政大學術集成

163

0

0

全文

(2) The Effect of the Test-question Preview Worksheets on Promoting Junior High School Students’ English Learning Motivation and English Achievement in a Test-oriented Learning Context. A Master Thesis. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大 Presented to. Department of English,. n. sit. er. io. al. y. ‧. Nat. National Chengchi University. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts. by Wan-chi Chang November, 2013.

(3) Acknowledgements. I want to present my deepest gratitude toward my advisor, Dr. Hsueh-ying Yu, who patiently read the drafts of my thesis again and again and offered many constructive suggestions in numerous meetings. Because of her endless guidance, support and encouragement, I could make my thesis more complete and improve my. 政 治 大. English writing skills simultaneously. Also, I would like to say thanks to the. 立. committee members, Dr. Hsi-nan Yeh and Dr. Chieh-yue Yeh , for going through my. ‧ 國. 學. manuscript and giving helpful advice that led me to make necessary modifications to the thesis.. ‧. I am especially grateful to my colleges and friends who gave me spiritual support. y. Nat. io. sit. and encouragement so that I could persist in writing the thesis when I encountered. n. al. er. difficulties—Ru-yu Wang, Mi-ting Xu, Yin-yin Gu and Su-mei Chen.. i n U. v. Finally, a huge thank-you with a big hug to my dearest grandparents, my parents. Ch. engchi. and parents-in-law, my uncle and aunts, my brother and cousins, especially my husband, Kai-chen Hsu, for being all around me, encouraging me and supporting me when I felt down and frustrated, without whom I wouldn’t have made it. This thesis is dedicated to them. Thank you all from the bottom of my heart. I love you.. iii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... iv List of Tables .............................................................................................................. viii List of Figures ................................................................................................................ x Chinese Abstract ........................................................................................................... xi English Abstract .......................................................................................................... xiii. 政 治 大. Chapter One: Introduction ......................................................................................... 1. 立. Background and Motivation .................................................................................. 1. ‧ 國. 學. Purpose of Study .................................................................................................... 3 Chapter Two: Literature Review ............................................................................... 5. ‧. Motivation .............................................................................................................. 5. Nat. sit. y. Three Traditional Perspectives on Motivation ............................................... 5. er. io. The Motivational Theories Based on Constructivist Perspective .......................... 8. al. v i n Expectancy-valueC Theory 11 h e ............................................................................ ngchi U n. Goal Theory ................................................................................................... 8. Self-efficacy Theory .................................................................................... 14 Attribution Theory ....................................................................................... 17 Self-determination Theory ........................................................................... 21 The Support for the Three Human Fundamental Needs in Education and Second/Foreign Language Learning ...................................................... 24 Autonomy ...................................................................................... 24 Competence.................................................................................... 27 Relatedness .................................................................................... 28 Learning Motivation Research in Taiwan............................................................ 31 iv.

(5) Worksheets Used in English Classes ................................................................... 33 Chapter Three: Methodology ................................................................................... 35 Participants ........................................................................................................... 35 Instruments ........................................................................................................... 36 The Principles for Designing the Test-question Preview Worksheets and the English Learning Motivation Questionnaire ................................................ 36 Test-question Preview Worksheets .............................................................. 38 The Test Section .................................................................................. 38 The Advanced Exercise Section .......................................................... 41. 政 治 大. The Student Self-evaluation Section .................................................... 42. 立. The Student/Teacher Feedback Section ............................................... 45. ‧ 國. 學. The Two Stages of Completing the Worksheets Learning .................. 46. English Learning Motivation Questionnaire ................................................ 48. ‧. A School-administered English Achievement Tests.................................... 50. sit. y. Nat. Data Analysis Methods ................................................................................ 50. io. er. Procedure ............................................................................................................. 53. al. Pilot Study.................................................................................................... 53. n. v i n The ProcedureC ofh the Pilot Study ........................................................... 53 engchi U The Results of the Pilot Study and the Modifications ........................... 54. The Test-question Preview Worksheets......................................... 54 The English Learning Motivation Questionnaire .......................... 55 Formal Study................................................................................................ 57 Chapter Four: Results and Discussion ..................................................................... 59 The Statistical Results of the English Learning Motivation Questionnaire . 59 The Changes of the Experimental High Group’s Three Motivational Components ................................................................................................. 61 The Changes of the Experimental Middle Group’s Three Motivational v.

(6) Components ................................................................................................. 65 The Changes of the Experimental Low Group’s Three Motivational Components ................................................................................................. 69 The Analysis of the Open Questions on the Test-question Preview Worksheets ........................................................................................................... 73 Discussion on the Findings of the Analysis on the English Learning Motivation questionnaire and the Test-question Preview Worksheets................................... 87 The Influence of the worksheet learning upon the Participants’ Autonomy for Learning English .................................................................................... 87. 政 治 大. High Group .................................................................................. 87. 立. Low Group ................................................................................... 93. 學. ‧ 國. Middle Group ............................................................................... 90. The Influence of the worksheet learning upon the Participants’ Competence. ‧. Perception .................................................................................................... 96. sit. y. Nat. High Group .................................................................................. 96. io. er. Middle Group ............................................................................... 98. al. Low Group ................................................................................. 100. n. v i n C worksheet The Influence of the upon the Participants’ Relatedness U h e n g learning i h c. with Their Classmates and the Teacher ..................................................... 103 High Group ................................................................................ 103 Middle Group ............................................................................. 104 Low Group ................................................................................. 106 Report and Discussion of the Results of the School-administered English Achievement Test ...................................................................................... 108 Chapter Five: Conclusion........................................................................................ 111 Summary of Major Findings ...................................................................... 111 Pedagogical Implications ........................................................................... 114 vi.

(7) Limitations of the Study............................................................................. 116 Suggestions for Future Research ............................................................... 117 References .................................................................................................................. 119 Appendixes ................................................................................................................ 131. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i n U. v.

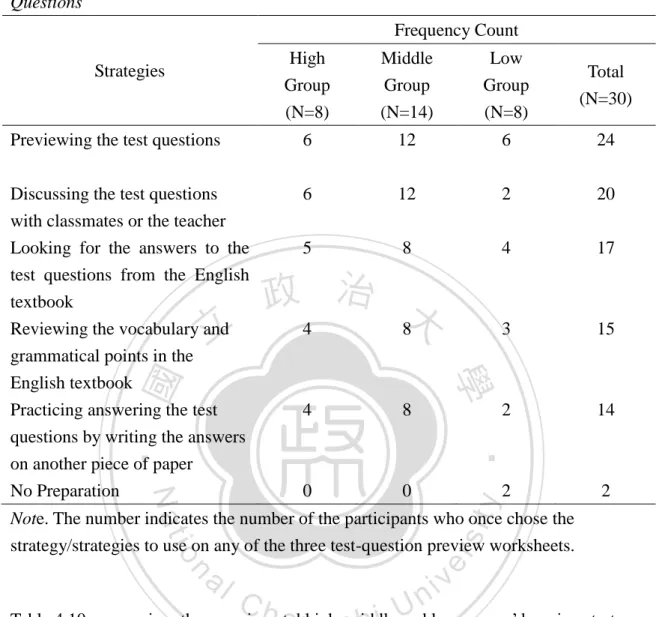

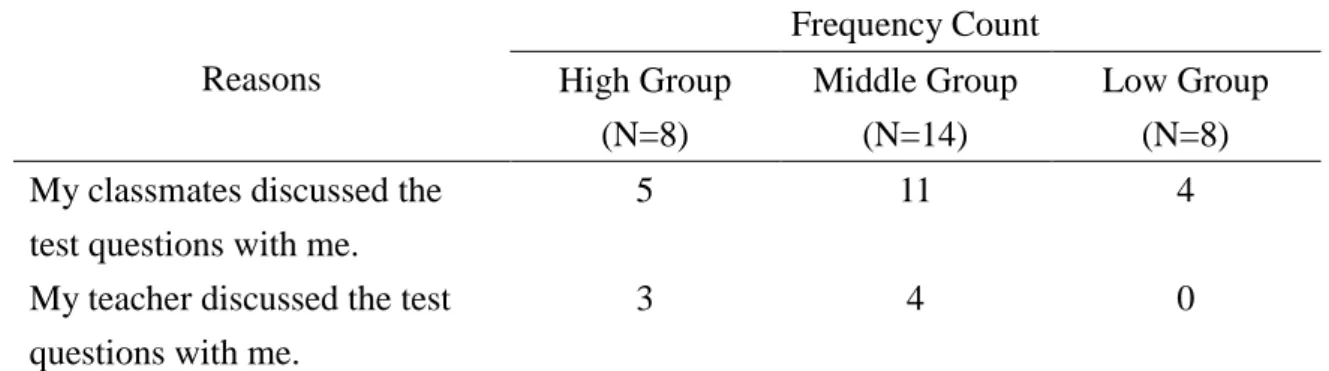

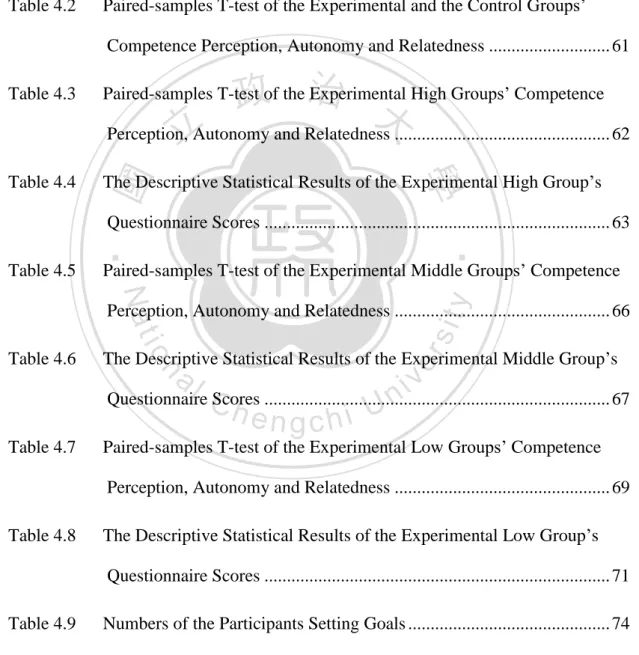

(8) LIST OF TABLES. Table 4.1. Independent-samples T-test of the Experimental and the Control Groups’ Competence Perception, Autonomy and Relatedness before the Treatment ............................................................................................... 60. Table 4.2. Paired-samples T-test of the Experimental and the Control Groups’ Competence Perception, Autonomy and Relatedness ........................... 61. Table 4.3. 政 治 大. Paired-samples T-test of the Experimental High Groups’ Competence. 立. Perception, Autonomy and Relatedness ................................................ 62. ‧ 國. 學. Table 4.4. The Descriptive Statistical Results of the Experimental High Group’s Questionnaire Scores ............................................................................. 63. ‧. Table 4.5. Paired-samples T-test of the Experimental Middle Groups’ Competence. y. Nat. er. io. The Descriptive Statistical Results of the Experimental Middle Group’s. al. n. Table 4.6. sit. Perception, Autonomy and Relatedness ................................................ 66. Ch. i n U. v. Questionnaire Scores ............................................................................. 67 Table 4.7. engchi. Paired-samples T-test of the Experimental Low Groups’ Competence Perception, Autonomy and Relatedness ................................................ 69. Table 4.8. The Descriptive Statistical Results of the Experimental Low Group’s Questionnaire Scores ............................................................................. 71. Table 4.9 Table 4.10. Numbers of the Participants Setting Goals ............................................. 74 Numbers of the Participants Using Learning Strategies for Preparing for the Test questions ............................................................................. 76. viii.

(9) Table 4.11 Numbers of the Participants Feeling Satisfied or Dissatisfied with the Test Results ............................................................................................ 78 Table 4.12. Numbers of the Participants Giving Reasons for Feeling Satisfied or Dissatisfied with the Test Results .......................................................... 79. Table 4.13 Numbers of the Participants Stating Gains from the Worksheet Learning ................................................................................................. 81 Table 4.14 Numbers of the Participants Giving Reasons for Feeling Thankful to Their Classmates and the Teacher ......................................................... 82. 政 治 大. Table 4.15 Numbers of the Participants Giving Feedback on the Worksheet. 立. Learning ................................................................................................. 84. ‧ 國. 學. Independent-samples T-test of the Experimental and Control Groups’/Subgroups’ Scores of the School-administered English. ‧. Achievement Test ................................................................................ 108. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Table 4.16. Ch. engchi. ix. i n U. v.

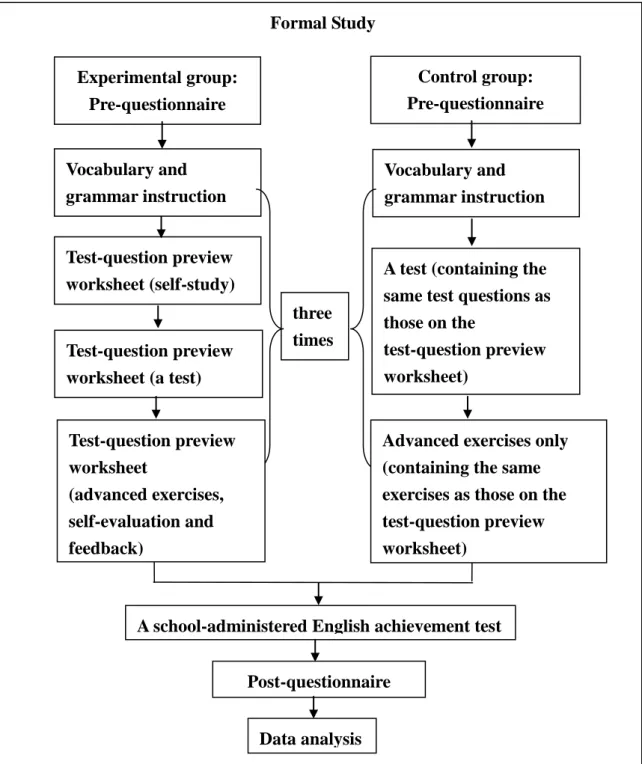

(10) LIST OF FIGURES. Figure 3.1 The Procedure of the Formal Study............................................................ 57. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(11) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱:考試導向的學習情境下試題預覽學習單對提升國中生英語學習動機與 學習成就之效益. 指導教授:尤雪瑛博士. 立. 研究生:張琬琪. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 論文提要內容:. ‧. 動機雖被認定為影響第二語言及外語學習的因素之一,然而如何在考試導向. y. Nat. sit. 的學習環境下提升學生內在或自主性英語學習動機的相關研究並不多。本研究依. n. al. er. io. 據自我決定理論(the self-determination theory)來設計學習單,用以輔助學生學習. i n U. v. 學校的一般英語課程,來探討自我決定理論在現行教育環境下使用的效益。此. Ch. engchi. 外,學習單的使用是否能幫助學生的成就表現優於其他學生也一併研究。 參與本研究的對象為台灣北部一所公立國中八年級兩個班的六十位學生。這 兩個班級有相似的社會背景及英語成就表現,並隨機被指定為實驗組與控制組。 實驗組可在考試前預覽印在學習單上的試題,而控制組則直接參與考試。本實驗 歷時七週,蒐集資料的工具包含問卷、學習單和該學校所舉辦的英語成就測驗(英 語段考)。研究方法含量化及質性分析,主要探討學習單對學生的三個英語學 習動機元素(autonomy, competence and relatedness)及英語成就表現的影響。 研究結果顯示高成就學生的主動性(autonomy)及中等成就學生的主動性 (autonomy)、自我感知的英語能力(perceived competence)以及與同儕、老師間的 xi.

(12) 相關性(relatedness)有提升。然而,低成就學生的三個英語學習動機元素則下降。 另外,實驗組在該學校所舉辦的英語成就測驗的表現和對照組相比並無明顯差 異。本研究最後對使用學習單提升學生內在或自主性學習動機在實際教學上的應 用提供建議,以作為參考。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xii. i n U. v.

(13) ABSTRACT Although motivation has been viewed as an important factor that affects second and foreign language acquisition, there isn’t much research investigating how to promote students’ intrinsic or more self-regulated motivation to learn English in test-oriented classroom settings. This study explores this area by complementing. 政 治 大 self-determination theory. Furthermore, it also investigates whether students with the 立. students’ regular English classes at school with the worksheets designed based on the. aid of the worksheets would outperform those not using the worksheets academically.. ‧ 國. 學. For this research purpose, two classes of 60 eighth-graders in a public junior high. ‧. school in northern Taiwan took part in this study. The two classes with similar social. sit. y. Nat. background and English academic performances were randomly classified into an. io. er. experimental group and a control group. The experimental group was given a chance to preview the test questions which were printed on the worksheets distributed to them. al. n. v i n C h the tests. The control as the complementary material before group, on the other hand, engchi U. was given the tests directly without the chance to preview the test questions. The experiment lasted for seven weeks, and the data were collected through three. instruments, a questionnaire, the worksheets, and a school administered-achievement test. Both quantitative and qualitative research methods were adopted to probe into the influence of the worksheets upon the participants’ three motivational components, namely autonomy, competence, and relatedness as well as their academic performance on the achievement test. The study results indicate that the worksheets could help promote the high achievers’ autonomy and the middle achievers’ autonomy, competence perception and xiii.

(14) relatedness, but they did not exert positive effects on the low achievers. Furthermore, the experimental group didn’t outperform the control group on the school-administered achievement test. Some pedagogical implications were presented at the end of the thesis.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiv. i n U. v.

(15) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION. Background and Motivation English has long been considered important and taught as a requisite subject matter in Taiwan’s compulsory education due to its popularity among international languages. However, students’ English learning outcomes in junior high schools are usually evaluated by tests and exams, serving as the preparation for the upcoming English test in. 政 治 大 entrance examination held by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan. Although a 立. the Basic Competence Test for Junior High School Students, a formal senior high school. 12-year compulsory education program has been initiated by MOE, and it is expected that,. ‧ 國. 學. in 2014, 75% of junior high school students can enter senior high schools without an. ‧. entrance examination, there is still going to be a formal exam used to classify junior high. sit. y. Nat. school students into at least three academic achievement levels. The higher levels students. io. er. can achieve, the better chance they will get to enter a small number of prestigious senior high schools. Therefore, it is still questionable whether the new compulsory education. al. n. v i n C hheavy test pressureUin the future. program can truly release students’ engchi. In the present test-oriented learning environment in Taiwan, junior high school. students are usually passive learners, studying English mainly for better test scores or to outperform their peers instead of valuing what they are learning. Thus, their English learning motivation is low or only triggered by externally-controlling events, like school tests or entrance exams. When the pressure derived from tests is absent, they tend to stop their pursuit of English proficiency because there are no external stimuli pushing them forward. Therefore, it is necessary for students to ―value learning, achievement, and accomplishment even with respect to topics and activity they do not find interesting‖ so that they could be more active in learning (Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier & Ryan, 1991, 1.

(16) p.338). In other words, enhancing the level of self-control in students’ learning motivation may release them from the external control of the tests and exams. According to self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985), if students can gain support for three innate needs, autonomy, competence and relatedness, from their learning environment, their intrinsic motivation for learning could be promoted. Take autonomy support for example, teachers can help students focus on their learning process rather than on how many points they get on tests (Brown, 2001). Thus, students can develop their desire and willingness to pay more effort and persist in their English acquisition. Many other studies. 政 治 大 academic performances (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Gardner, 1985; Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). 立. have also demonstrated that more self-determined motivation could improve students’. Although it is acknowledged that autonomous forms of motivation could help. ‧ 國. 學. students become active learners free from the control and pressure of tests, high school. ‧. teachers have little ideas about practical ways to help students promote such kind of. sit. y. Nat. motivation for learning English in the test-oriented and competitive junior high school. io. described:. er. classrooms in Taiwan. This situation coincides with the dilemma Brophy (2010) have. al. n. v i n C h facing teachers isUto find ways to encourage their The motivational challenge engchi students to seek to develop the knowledge and skills that learning activities. were designed to develop, whether or not they enjoy the activities or would choose to engage in them if other alternatives were available. (p.xii) Therefore, the present study ventures to motivate the junior high school students who learn English in test-oriented classroom settings by designing worksheets to support their autonomy, competence perception and relatedness.. 2.

(17) Purpose of the Study The study firstly aims to explore whether junior high school students in a test-oriented learning context would promote more self-regulated motivation for learning English with the aid of the test-question preview worksheets. This study investigates how different levels of students (i.e. high, middle and low achievers) are affected by the worksheets, and which aspects of their English learning motivation would be improved. Secondly, the researcher intends to know whether the students who use the worksheets demonstrate better academic performances than those not using the worksheets. The. 政 治 大 1. Is students’ English learning motivation promoted after the use of the test-question 立. purposes can be briefly stated in the following two questions:. preview worksheets in a test-oriented learning environment?. ‧ 國. 學. 2. Do the students using the test-question preview worksheets outperform those not. ‧. using the worksheets on a school-administered English achievement test?. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 3. i n U. v.

(18) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 4. i n U. v.

(19) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW. This chapter offers a general review of three traditional perspectives on motivation, and the prominent motivational theories under those perspectives. In addition, the comparison among those theories is also mentioned.. Motivation. 政 治 大 of behavior as well as the quality, intensity, and persistence of the behavior (Maehr & 立. Motivation is a psychological construct used to account for the need and purpose(s). Meyer, 1997). Three motivational concepts underlying this mental construct are motives,. ‧ 國. 學. goals and strategies. According to Thrash and Elliot (2001), motives are general needs or. ‧. desires that offer people momentum to perform particular actions, but goals and strategies. sit. y. Nat. are relatively specific. They are used to describe the immediate objectives of a course of. io. er. actions (i.e. goals) and the means adopted to realize the goals and satisfy the motives (i.e. strategies). Take the general need for water for example. A person reacts to the feeling of. al. n. v i n C h a drink in a convenience thirst (the need for water) by purchasing store (strategy) to engchi U. quench that discomfort (goal). Much research has investigated into humans’ motivation for conducting behavior from different perspectives, and several prominent motivational theories were thus developed. The evolvement of the motivational theories can be seen from three traditional perspectives on motivation.. Three Traditional Perspectives on Motivation Motivation is interpreted differently from behavioral, cognitive and constructivist perspectives. In the view of behaviorists, behavior is contingent on its consequences (Thorndike, 1898). If the consequences are desirable, the behavior that brings about such 5.

(20) consequences is more likely to be performed. Grounded on this theoretical base, Skinner (1974) proposed behavior reinforcement theory in which by manipulating consequences into reinforcers, like external rewards, or punishments, certain behavior or a sequence of actions would be increased, maintained or decreased. In other words, the outer forces, such as rewards and punishments, serving as an external control, could motivate people to carry out certain actions passively. Skinner further expanded behavior reinforcement theory by introducing the concept of stimulus control in which irrelevant external cues, like ringing sounds, could serve as signals that stimulate people to conduct certain. 政 治 大 interpreted as a kind of control rather than mental power. 立. reinforced actions for getting anticipated reinforcers. Thus, motivation to behaviorists is. Behavior reinforcement theory is widely applied in classroom settings nowadays, but. ‧ 國. 學. the effectiveness of the applications is often questionable. The approaches adopting the. ‧. behavioral view are known as carrot-and-stick approaches which suggest teachers to. sit. y. Nat. reinforce students when they perform desired behavior and to take away the positive. io. er. reinforcers or give punishments when they fail to perform it (Schloss & Smith, 1994). For example, many token economies, systematical ways of behavior shaping, have been. al. n. v i n Ctohimprove or modifyUstudents’ social or learning developed by classroom teachers engchi. behaviors. When students perform the target actions or improve their behavior to a certain degree, they are rewarded with tokens, such as money or extra time for recreation. Many studies have proved the effectiveness of token economies in classroom settings (Abramowitz & O’Leary, 1991; Kazdin, 1975; O’Leary, 1978; Williams, Williams, & McLaughlin, 1991). However, several researchers have cautioned that carrot-and-stick approaches, like token economies, might have detrimental effects on behavior modification and learning (Kazdin, 1988; Kazdin & Bootzin 1972; O’Leary & Drabman, 1971). They doubt whether the behaviors would continue when the token economies are no longer offered. In their studies, those encouraged actions or shaped 6.

(21) behaviors often decreased rapidly after the tokens were removed. Furthermore, Harter (1978) in his study has proposed that extrinsic rewards might urge students to choose less challenging tasks because by doing so, it would be easier for them to get the rewards. Eisenberger (1992) has warned that teachers might accidently foster students’ low levels of efforts to achieve a task because it is difficult for teachers to assess how much effort a student should exert on a task is adequate, especially in a large class. Kohn (1993) also claimed that there would be a lasting negative influence on students’ motivation to learn if students rely too much on tangible rewards or punishments to perform achievement. 政 治 大 it changes students’ focus from enjoying learning to winning praise from others. 立. behavior. For example, praise may interfere with students’ intrinsic motivation to learn for. From cognitive perspective, motivation to perform behavior (or a course of actions). ‧ 國. 學. is not entirely controlled by external contingencies. Instead, it’s mainly influenced by. ‧. individual intentions, thoughts and subjective experiences. Cognitive theorists believe. sit. y. Nat. that reinforcement could only be effective when external contingencies are responsive to. io. er. needs, personally valued and considered achievable. Need theory was thus developed to alternate reinforcement theory. In the theory, motivation is derived from individual felt. al. n. v i n C h or developed through needs, which may be innate, universal personal experiences, and is engchi U self-determined. Thus, people make their own choices about which felt needs to fulfill and how much effort to make for satisfying them. Ausubel (1968), in his drive theory, proposed that human beings have six inherent needs, which are the needs for exploration, manipulation, activity, stimulation, knowledge, and ego enhancement. They give people the driving force, namely motivation, to initiate certain behaviors to meet those inner needs. The belief of motivation as an internal individual force is not comprehensive from the constructivists’ point of view due to its absence of the influence of the social context on human motivation. To be more complete, need theory would have to be expanded to 7.

(22) take social factors into consideration. One of the famous need theories reflecting this point is Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of human needs. He suggested that human beings have a system of needs arranged in a hierarchy from physiological needs as the bottom through safety needs, love needs and esteem needs, and self-actualization as the top. Among them, some needs are interacted with the society, like the need for belongingness in love needs. This expanded view of human needs is more comprehensive to elaborate the conception of motivation for it concerns not only the innate needs and personal choices of which needs to fill, but also the interaction between the needs and the social. 政 治 大 Since constructivist perspective, concerning the influence of both cognitive and 立. contexts.. social factors on motivation, is more complete than behavioral and cognitive perspectives,. ‧ 國. 學. the following sections would focus on introducing and comparing other motivational. ‧. theories under the constructivist framework.. sit. y. Nat. io. er. The Motivational Theories Based on Constructivist Perspective This section introduces and compares five well-known motivational theories that are. al. n. v i n Cperspective. all developed from constructivist are goal theory, self-efficacy theory, h e n g cThey hi U expectancy-value theory, attribution theory and self-determination theory.. Goal Theory Compared with behavior reinforcement theory and need theory, which focus on human reactions toward either external contingencies or internal needs, goal theory emphasizes more on people’s proactive tendency to determine the reasons for performing certain behavior and the ways to perform it. People carrying different purposes may develop different goals. When applied in education, goal theory is often related to the distinction between learning goals and performance goals (Ames, 1992; Ames & Archer, 8.

(23) 1988; Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Learning goals may be derived from students’ interest in the activities, identified values consistent with the objectives of the activities or awareness of the utility of the knowledge or skills the activities aim to teach. Thus, students who bear learning goals in mind place stress upon acquiring knowledge and skills when undertaking activities. To reach their learning goals, they would adopt deep processing strategies, such as comprehending the learning contents by paraphrasing them in their own words and associating their newly-learned knowledge and skills with prior ones (Meece, Blumenfeld, & Hoyle, 1988). When encountering difficulties, they are. 政 治 大 overcome the obstacles (Dweck, 1986). 立. prone to maintain their efforts and look for appropriate problem-solving strategies to. In contrast, students who emphasize on enhancing and protecting their. ‧ 國. 學. self-perceptions and social reputation often set performance goals (Butler, 1992). They. ‧. participate in the activities mainly for displaying their ability and intelligence or. sit. y. Nat. preventing themselves from being considered incompetent. In order to reach performance. io. er. goals, they tend to adopt surface-processing strategies, such as memorizing the learning contents, to meet the basic demands of the activities more easily and effectively (Meece,. al. n. v i n Blumenfeld, & Hoyle, 1988). IfC allowed to choose tasks, h e n g c h i U unlike learning-oriented students, they would avoid challenging tasks because they couldn’t afford the risk of failure (Ames & Archer, 1988; Elliott & Dweck, 1988; Smiley & Dweck, 1994). For performance-oriented students, failure often indicates low ability, and it impairs students’ self-perceptions and social approval. Therefore, they would strive to shun away from such situations as much as possible. However, when confronting unavoidable difficulties, performance-oriented learners would be more likely to be affected by their fear of failure and reduce their efforts exerted on the tasks. They may easily give up or conceal their incompetence by taking self-defeating strategies, like not studying much or leaving the answer sheets blank (Dweck, 1986). 9.

(24) Much research has proposed that learning goals would be more beneficial than performance goals in classroom settings because students with learning goals focus on developing ability rather than displaying ability or worrying about failure (Dweck, 1986; Kaplan & Maehr, 2007; Linnenbrink & Pintrich, 2002; Wolters, 2004). However, other studies have found that performance goals which emphasize on achieving success (also called performance-approach goals) could complement learning goals (Harackiewicz, Barron, Tauer, Carter, & Elliot, 2000; Valle et al., 2003). Learning goals have been found correlated with some desirable learning features, like interest in school materials and. 政 治 大 and future involvement in relevant learning fields. Nevertheless, they place less stress 立. activities, deep processing strategies, long-term retention of learned knowledge and skills,. upon short-term achievement performance evaluated based on the criteria set by teachers. ‧ 國. 學. or schools. This could be complemented by performance-approach goals. Thus, a. ‧. multiple-goal perspective is developed and supported by some goal theorists for it. io. er. 1990; Senko & Harackiewicz, 2005; Senko & Miles, 2008).. sit. y. Nat. combines the merits of learning goals and performance-approach goals (Entwistle & Tait,. Although such complement seems more complete and beneficial, Midgley, Kaplan,. al. n. v i n and Middleton (2001) cautionedC that the negative effects h e n g c h i U of performance-approach goals. couldn’t be ignored. They may divert students’ attention from learning to competition and. orient students toward taking less challenging tasks to avoid failure. Even worse, if students consistently experienced failure, their performance goals might only focus on avoiding failure rather than achieving success. Shim, Ryan, and Anderson (2008) have advised that by modifying instruction or school curricula to increase students’ value of the agenda set by teachers and schools, students with learning goals could improve their class performance. This is better than promoting students’ performance-approach goals as a complement to their learning goals. For the long-term learning profit, learning goals are still more preferable than performance goals. 10.

(25) Goal theory places its attention on individuals’ purposes for their goal-oriented behavior, the features of such behavior and the possible consequences of it. The next motivational theory, on the other hand, not only considers the purposes (i.e. value) but also the possibility of success or failure in reaching the purposes (i.e. expectancy).. Expectancy-value Theory Expectancy-value theory is another prominent motivational theory developed from constructivist perspective. It especially concerns two motivational constructs, expectancy. 政 治 大 and choice. Atkinson (1957) proposed the first formal expectancy-value model. In the 立. and value, which are believed to be able to predict achievement performance, persistence. model, achievement-related behaviors are determined by two stable unconscious factors,. ‧ 國. 學. motive for success and motive to avoid failure, and two situational conscious factors,. ‧. expectations for success/failure and incentive values. Motives for success and to avoid. sit. y. Nat. failure are viewed as stable dispositions that unconsciously lead individuals either to. io. er. engage in tasks for success or to evade tasks for avoiding failure in achievement contexts. Such tendencies are gradually formed in childhood according to the ways parents use to. al. n. v i n C h children to make raise their children. If parents encourage efforts to achieve success in engchi U achievement tasks and give them opportunities to apply their competence to reach the goals, motive for success would develop. On the contrary, if children are forced to perform well in tasks, or they will be punished, motive to avoid failure would be established.. Besides the two motives that influence individuals’ tendency to approach or avoid an achievement-related activity, the other two situational conscious factors, expectancy beliefs and incentive values could also affect individuals’ decisions to strive for success or avoid failure in an achievement situation. Expectancy beliefs are individual judgments of the possibility of success in achievement tasks and thus include expectations for success 11.

(26) and for failure. If people expect the chance for success in a task is high, they are more likely to approach it rather than avoid it. As for incentive values, they refer to the expectations of pride and shame and have an inverse relationship with expectations for success and failure. Atkinson postulated that people would experience greater pride if they succeed in an achievement task with a low possibility of success. On the other hand, greater shame would be experienced if people fail in an achievement task with a high possibility of success. Though Atkinson’s model provides a way to explain individuals’. 政 治 大 unconscious factors, motive for success and motive to avoid failure, are hard to measure. 立 achievement-related behaviors, there are several problems in the model. First, the two. Second, the inverse relationship between expectancy for success or failure and incentives. ‧ 國. 學. values may be questionable. Some studies have presented that both factors are positively. ‧. related and thus suggested that individuals value the tasks that they have great possibility. sit. y. Nat. to succeed (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995; Wigfield & Eccles, 1992). Third, the definition of. io. er. incentive values is too narrow because the values are solely determined by the height of the expectancy for success without considering other possible factors, such as usefulness. al. n. v i n C h task aims toUdevelop. Wigfield and Eccles of the skills or knowledge an achievement engchi. (1992) have expanded the definition in their expectancy-value model by proposing the concept of task values which contains four major components to illustrate the qualities of the achievement tasks. They are attainment value (the importance of the task), intrinsic value (the enjoyment of engaging in the task), utility value (usefulness of the task) and cost (the cost for doing the task). In education, expectancy-value theory can also be applied to account for students’ achievement-related behaviors in school activities. Hansen (1989) suggested four kinds of behaviors that could be found in students in accordance with their expectations and values. The behaviors include engaging, dissembling, evading and rejecting behaviors. First, 12.

(27) engaging behaviors often appear when students value the school activity and feel confident in achieving success. They would absorb themselves in acquiring the knowledge and skills when doing the activity and view unfamiliar parts as challenges and chances to develop their ability. Second, dissembling behaviors occur when students see value in the school task but are not confident of completing it successfully. In such a situation, students tend to protect their self-esteem by pretending they are capable of doing the task rather than develop their ability. They may make excuses or perform self-defeating actions, like exerting little effort on a task. Third, students show evading. 政 治 大 no reason to do it. Thus, in the process of completing the activity, they are easily 立. behaviors when they feel competent in achieving success in the school activity but have. absent-minded or distracted by things or activities they are more interested in, such as. ‧ 國. 學. chatting with classmates. Last, rejecting behaviors could be found in the students who. ‧. don’t value the school activity as well as have a low success expectation. Such students. sit. y. Nat. are passive in doing the task and tend to give up completely even without an intention to. io. er. pretend their efforts.. In short, based on expectancy-value theory, it is suggested that students could. al. n. v i n C hbehaviors if they areUassisted in appreciating the value improve their achievement-related engchi of the school activities as well as in believing they are capable of achieving success.. The major focus in expectancy-value theory is on the two motivational constructs believed to influence individuals’ motivation to conduct achievement-related behavior. The following motivational theory, self-efficacy theory, turns its attention on one motivational construct, self-efficacy, considered more influential than other factors in predicting individuals’ motivation and achievement behavior.. 13.

(28) Self-efficacy Theory Self-efficacy is a psychological construct proposed by Bandura (1977). It refers to personally-perceived capabilities for reaching certain goals, or completing a task successfully. Much research has found that self-efficacy might be a powerful predictor of individuals’ motivation, self-regulation behaviors (e.g. set goals, evaluate learning progress), and achievement (Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991). With a high sense of self-efficacy, people tend to choose challenging tasks (Sexon & Tuckman, 1991), persist longer, use more cognitive and problem-solving strategies (Bandura, 1993), and involve. 政 治 大 would assist people in attaining their achievement outcomes (Zimmerman, 1995). The 立 in self-regulated learning (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990). These positive consequences. successful attainments would subsequently bring positive personal experiences that. ‧ 國. 學. enhance self-efficacy and encourage people to make progress in the future. Therefore,. ‧. self-efficacy is a relatively influential factor worth cultivating in achievement settings.. sit. y. Nat. Bandura (1997) suggested a set of ways to increase self-efficacy. They include (a). io. er. encouraging students to take optimal challenges through setting clear, achievable but challenging goals, (b) making sure students know how to deal with the challenging tasks. al. n. v i n C hstrategies, (c) giving by modeling or implying the useful positive informative feedback engchi U. that encourages students to approach success, and (d) helping students to recognize that their ability is progressing through taking the optimal challenges, investing effort and persisting in them. In the process of increasing students’ perceptions of self-efficacy, students would simultaneously improve their motivation and engagement in school activities. The sources of information that people obtain to judge their self-efficacy include actual performances, vicarious experiences, social persuasion and physiological arousal (Bandura, 1997). The information gained from actual performances, such as success and failure, is a more dependable source for judging self-efficacy because it comes from 14.

(29) direct personal experiences. Success or positive experiences tend to raise self-efficacy and failure or negative experiences often lower it. However, there might be some exceptions (Earley & Lituchy, 1991). For example, succeeding in an easy task or attributing the success to uncontrollable causes, like luck or others’ help, wouldn’t raise one’s self-efficacy. Vicarious experiences provide another source of information that helps people gauging their self-efficacy. Observing similar individuals succeed or fail in a task offers a clue for the observers to judge their capabilities for doing similar tasks (Schunk, 1995). If. 政 治 大 tasks as well. Nevertheless, the observers’ self-efficacy may decrease if the task results 立. the similar others succeed, the observers tend to believe they can succeed in doing similar. don’t correspond with their judgments of their own capacities. Though not as direct as. ‧ 國. 學. actual performances, vicarious experiences would be more influential when people have. ‧. little prior individual experiences with the tasks (Bandura, 1986).. sit. y. Nat. Social persuasion given by important or credible people can also affect the judgment. io. er. of self-efficacy. Positive social persuasion may increase self-efficacy while negative social persuasion may decrease it. However, positive social persuasion wouldn’t exert its. al. n. v i n C hand trustworthy. Unlike desirable effect unless it is realistic empty praise, good positive engchi U. social persuasion can provide solid information, such as persuaders’ real experiences, to enhance people’s beliefs in their own capacities and assure them that the goals they are to achieve are attainable. If the goals are subsequently successfully realized, the promoted feelings of self-efficacy would remain, but if not, self-efficacy beliefs would be weakened (Schunk, 1995). The last source of information that influences one’s sense of self-efficacy is physiological arousal. People tend to generate certain physiological and emotional reactions toward the action or task they are going to do. If the reactions are stress, anxiety, fear or negative thoughts, self-perception of efficacy would reduce. The lowered sense of 15.

(30) efficacy might in turn engender extra stress and anxiety which negatively affect the consequences of their actions or task performances. The poor consequences would reassure people that their efficacy is low when they are in similar conditions. Thus, the way to prevent the vicious circle is to improve people’s physiological and emotional reactions before they engage in an action or a task. Overestimating or underestimating one’s self-efficacy might result in negative consequences. People who overestimate their capacities and then experience subsequent failure may lower their motivation to do similar tasks. On the other hand, underestimated. 政 治 大 tend to choose the tasks that they think they are capable of handling and avoid the ones 立. self-efficacy might directly lower one’s motivation to perform the task because people. they feel too difficult for them (Bandura, 1993). Though relatively precise self-efficacy. ‧ 國. 學. judgment seems more preferable, Bandura (1997) further contended that individuals. ‧. would expend more effort and persist longer if their self-efficacy is slightly higher than. y. sit. io. er. in many studies.. Nat. what they can do, which echoes the support for providing optimal challenges to learners. Though self-efficacy has been considered as a relatively influential factor that affects. al. n. v i n individuals’ achievement-relatedCbehaviors, there are still h e n g c h i U many other factors that would also interfere with people’s achievement actions (Bandura, 1997). For example, people. with adequate self-efficacy may perform a task poorly if they don’t value the task or expect positive outcomes. Schunk (1995) proposed that self-efficacy would show its effect on people’s motivation more saliently when the influence of other factors, like value or outcome expectations, is reduced. In sum, it has been proved that self-efficacy plays an important role in determining motivational actions in achievement situations, but it wouldn’t be comprehensive to describe individuals’ motivational states if other factors are ignored.. 16.

(31) Similar to self-efficacy theory that emphasizes one motivational construct, the next motivational theory, attribution theory, focuses on the motivational factor, to know the causes of success or failure in an achievement context. It is proposed that by knowing the reasons for the consequences of behavior, individuals’ motivation for doing similar or relevant tasks in the future would be influenced (Weiner, 1992).. Attribution Theory The concept of causal attribution was first introduced by Fritz Heider (1958) and. 政 治 大 look for the reasons for the consequences of their behaviors, especially when their 立. elaborated by Bernard Weiner (1986). It is based on the belief that humans spontaneously. behaviors are inconsistent with their expectations (Whitley & Frieze, 1985; Weiner, 1985,. ‧ 國. 學. 1992). Such attributions may affect their future behaviors in similar situations. Hence, in. ‧. achievement settings, attribution theorists tend to analyze three areas — the features of. sit. y. Nat. self-perceived causes, the factors that make individuals conclude certain attributions. io. er. toward their success and failure, and the influence of such attributions on future performances. Based on the analyzed results, individuals’ motivation to perform certain. al. n. v i n Ccan actions in achievement situations and some motivational strategies U h ebenexplained, i h gc aiming to promote motivational states are proposed accordingly.. Weiner’s attribution theory (1992) also focuses on these three areas. It comprises three causal dimensions, attributional antecedents, and consequences of attributions. The three causal dimensions, namely locus, stability and controllability, are the underlying features of causes used to account for why certain causal attributions to success or failure are beneficial and others are detrimental to people’s achievement motivation. First, locus pertains to the distinction between internal and external causes. Internal causes, such as ability and effort, are originated from individuals themselves while external causes, like luck or help from others, come from outside. Second, stability refers to the differentiation 17.

(32) between the causes constant in different situations and the ones varying with situations. Ability is often considered as a stable cause whereas effort, luck and others’ help as unstable causes. Third, controllability is connected to whether the causes of outcomes are controllable or incontrollable by individuals. For example, effort is a controllable cause, and ability is an incontrollable cause. Attributional antecedents, consisting of situational factors and individual differences, interfere with people’s perceptions of their success and failure to reach certain causal attributions. Situational factors, like teachers’ feedback and peers’ consensus, are the ones. 政 治 大 low ability cues in their feedback when showing sympathy to failing students, offering 立. whose antecedent information comes from contexts. Teachers may accidentally convey. help when students don’t need it, and giving praise for success in easy tasks (Graham,. ‧ 國. 學. 1990). Sympathy from others is often associated with uncontrollable causes, like low. ‧. ability, and thus implies the need of help. Therefore, showing sympathy to students who. sit. y. Nat. fail in a task or providing them with unsolicited help would produce indirect messages. io. er. that the teacher thinks his/her students lack ability (Graham, 1984; Rudolph, Roesch, Greitemeyer, & Weiner, 2004). Since ability is stable and uncontrollable, students might. al. n. v i n reduce their effort to do similar C tasks in the future because h e n g c h i U they believe nothing they can do to reverse the outcomes. Praise from teachers for students who succeed in easy tasks. may also elicit the same causal attribution, lack of ability, because such praise implies that teachers don’t think the easy tasks are easy for students (Barker & Graham, 1987). In addition, peers’ consensus can also have the effect on causal attributions. For example, if everyone is given a good grade on a test, the cause of the success would be influenced by a consensus that the test result is derived from external uncontrollable causes, like an easy test, rather than internal causes, like effort or ability. As for another type of attributional antecedents, individual differences, they often refer to a distinction between personal beliefs in entity theory of ability and incremental 18.

(33) theory of ability. Entity theorists hold that ability is an unchangeable fixed entity that wouldn’t grow over time or with their exerted effort. Thus, they tend to worry about how much ability they have in a specific area. In contrast, incremental theorists view ability as an unstable modifiable trait that the more effort they invest the better ability they may develop (Dweck & Molden, 2005). Many attribution retraining studies have proposed that incremental theorists often achieve better academic performances than those who believe in entity theory of ability ( Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007; Forsterling, 1985; Good, Aronson, & Inzlicht, 2003).. 政 治 大 achievement outcomes to effort or ability. Weiner (1992) has pointed out that success or 立 Consequences of attributions often concern the consequences of attributing. failure in achievement situations is commonly attributed to two causes, ability and effort.. ‧ 國. 學. Ability is often defined as an internal, stable and uncontrollable cause. On the other hand,. ‧. effort is perceived as an internal, unstable and controllable cause. Attributing achievement. sit. y. Nat. outcomes to effort is generally considered more important than attributing the outcomes. io. er. to ability (Weiner, 1994). Failure attributed to lack of effort indicates that if more effort is invested, there is still a good chance to succeed. This implication can lessen the threat of. al. n. v i n C hexpended on the similar self-esteem and trigger more effort tasks in the future. engchi U. On the contrary, failure ascribed to low ability usually indicates that the possibility. of succeeding in the similar tasks is low, because ability is considered to be stable and uncontrollable. Even worse, such low ability attributions may damage self-esteem. In order to protect self-esteem, individuals would take self-handicapping strategies, like playing all day before a test, to intentionally place obstacles in their achievement performances. By doing so, failure is more likely to be attributed to the causes other than low ability (Elliot & Church, 2003). When individuals have experienced a great deal of failure and attributed it to low ability, they tend to develop a sense of helplessness. In such vulnerable mental state, they would give up easily and refuse others’ help when 19.

(34) encountering difficulties (Diener & Dweck, 1978; Licht & Dweck, 1984). Furthermore, failure attributed to effort is associated with feelings of guilt while failure ascribed to ability is related to feelings of shame. Guilt tends to generate the inclination to increase effort, but shame often makes people desire to decrease effort or simply give up a task (Covington & Omelich, 1984; Weiner, 1992). Success attributed to effort (or other controllable causes) is also more constructive than that attributed to ability (or other uncontrollable causes). Since effort is a controllable cause, individuals who make effort to attain success may have more. 政 治 大 to ability or other uncontrollable causes may reduce such confidence because being 立. confidence in achieving success in the future. However, attributing success performances. successful or not is not determined by their own effort that they can control (Diener &. ‧ 國. 學. Dweck, 1980).. ‧. Teachers can follow the implications of attribution theory to promote students’. sit. y. Nat. motivation to learn and perform better at school. They can guide students to attribute. io. er. success or failure to internal and controllable causes, like effort. When helping students, teachers can show the students how efforts work from their previous performances or. al. n. v i n C has a proof of the importance design an achievable task for them of efforts (Brophy, 2010). engchi U Gradually, they would increase their self-esteem and become more willing to make effort and persist in a school task. Attribution theory stresses upon one motivational construct, the perceived causes of success and failure, to elaborate its potential to influence motivation. The next motivational theory, self-determination theory, on the other hand, starts with three basic psychological needs, then directly focuses on motivation as a whole and classified it into different types of motivation in accordance with the degrees of internalization.. 20.

(35) Self-determination Theory Self-determination theory is based on an assumption that humans have an inherent propensity to learn about outer environment through developing the knowledge of it and assimilating social practices (Ryan, 1995). Such inherent tendency (also regarded as autonomous motivation, including intrinsic motivation) would grow and remain when three basic psychological needs, namely autonomy, competence and relatedness, are satisfied (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The satisfaction of the basic needs can motivate people to participate in social activities and to identify with the values or regulations from outer. 政 治 大 identifying themselves with the social values and regulations and get integrated into the 立. environment. With the continual support for the three needs, people would keep. context. The process of identification and integration is called internalization in the theory.. ‧ 國. 學. (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000). On the contrary, if the three innate needs are thwarted,. ‧. humans’ natural tendency to learn and develop would be undermined. Thus, it has been. sit. y. Nat. suggested that if contexts can provide support for the three inherent needs, people can. io. er. become more self-determined and intrinsically motivated to engage in the things they do (Deci, Vallerand, Pelletier & Ryan, 1991). In this regard, the three human innate needs. al. n. v i n C h components inUself-determination theory. could be perceived as three motivational engchi. Autonomy, one of the basic needs, means being self-directed in making choices or. plans as well as in taking actions. Another need, competence, pertains to knowing how to attain the desired outcomes and feeling capable of performing requisite behaviors to achieve them. Finally, relatedness refers to building a sense of security and the satisfactory closeness with other people around in the society. Among the three components, the support for autonomy needs is considered more important for it also helps integrate the internalized social regulations and values into the sense of self (Deci, Eghrari, Patrick, & Leone, 1994, Ryan & Deci, 2006). Therefore, the satisfaction of autonomy needs is viewed as the prerequisite to intrinsic motivation. In education, much 21.

(36) research has also confirmed the positive effect of autonomy support on the promotion of students’ intrinsic motivation to learn (Hardre et al., 2006; Reeve & Jang, 2006; Sheldon & Krieger, 2007; Williams & Deci, 1996). According to the degrees of internalization, several types of motivation are proposed and placed along a continuum of relative autonomy to visually illustrate the difference among them and to imply the possibility of moving from one end to the other with the support of the three basic needs (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Many studies investigating the relationship among different forms of motivation have supported the concept of. 政 治 大 Grouzet, & Pelletier, 2005). There are three major types of motivation, namely intrinsic 立 organizing motivation types along a continuum (Guay, Ratelle, & Chanal, 2008; Otis,. motivation, extrinsic motivation and amotivation. Intrinsic motivation is an optimal form. ‧ 國. 學. of internalization in that the regulations on an individual’s behaviors are fully internalized. ‧. and integrated into the sense of self. In this state, people have an interest in what they are. sit. y. Nat. doing and immerge themselves in the satisfaction and pleasure derived from the process. io. er. of doing it. As for extrinsic motivation, it often appears when behavior is externally regulated. The effort people exert is to fulfill the demands of external events or personal. al. n. v i n C h achieving a career, valued goals, like winning an award, or assimilating into the target engchi U language community. On the other hand, amotivation is characterized as lack of. motivation or intention to perform target behavior. People in the state of amotivation tend to escape from doing the required tasks because they see no value and have no interest in the tasks, and even if certain external rewards or punishments exist, such extrinsic motivators still fail to motivate them. Judging from the extent of outer regulation or different degrees of internalization, self-determination theorists divide extrinsic motivation into four subtypes: external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and integrated regulation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). The first two subtypes with lower levels of internalization are viewed as 22.

(37) controlled motivation, and the last two, including intrinsic motivation, with higher levels of internalization as autonomous motivation. First, external regulation involves the least self-determination. People merely act to meet a certain demand or requirement. Second, introjected regulation represents a form of regulation which is partially internalized and serves as internalized demands placing pressure upon people. Under such mental pressure, they would unwillingly perform certain socially-expected behavior so as to gain social approval or protect self-esteem. Third, indentified regulation involves more self-determination than the former two. 政 治 大 regulations of the target behavior as their own, but not feel them as an external or internal 立 types. People would develop indentified regulation when they adopt the values or. control. Thus, they would willingly perform behaviors so as to attain their. ‧ 國. 學. personally-valued goals. Fourth, integrated regulation is an optimal form of. ‧. internalization. It is thoroughly self-determined and would fully engage people in doing. sit. y. Nat. target activities. Such regulation is developed when people fully internalize and integrate. io. er. the values and regulations of the target behaviors. Therefore, people perform the target behaviors naturally and spontaneously without the feelings of being controlled.. al. n. v i n C hstudents’ intrinsic motivation Solely striving for promoting is not realistic because in engchi U. reality, not every school activity is interesting to students and able to create recreational enjoyment. Some of them are meaningful and worthwhile but not interesting to be engaged in for they are mainly designed to develop necessary knowledge and skills. Losier and Koestner (1999) suggested that the activities that are socially valued but not. seem interesting necessarily, such as an election, would be done more successfully under identified regulation than with intrinsic motivation. Otis et al. (2005) studied a group of high school students’ reasons for going to school from the eighth to tenth grade. The result showed that most of the students’ reasons reflected indentified regulation through out three years, manifesting that the common reasons for going to school were not for fun 23.

(38) but for instrumental reasons, like accumulating necessary knowledge and skills to get good jobs in the future. Deci and Ryan (1985) further contended that if people’s self-regulated motivation has been sufficiently promoted, external rewards may even be instrumental to developing intrinsic motivation. However, though extrinsic incentives may be more appropriate in certain circumstances and can complement motivational strategies to promote intrinsic motivation, most motivation theorists are still in favor of promoting intrinsic motivation, at least more self-determined forms of motivation. For example, Brown (2001) recommended more self-regulated motivation types, including. 政 治 大 teachers to provide adequate support for the three basic psychological needs, namely 立. intrinsic motivation, to learn a second or foreign language. Therefore, it is important for. autonomy, competence and relatedness, so that students can develop more. ‧ 國. 學. self-determined motivation and even their intrinsic motivation to learn.. ‧. sit. y. Nat. The Support for the Three Human Fundamental Needs in Education and. io. er. Second/Foreign Language Learning. Many researchers, based on the self-determination theory, probed into the correlation. al. n. v i n between the three human innateC needs (i.e. autonomy, U h e n g c h i competence and relatedness) and. education, including second/foreign language acquisition. This section centers on. reviewing the ways to support the three human fundamental needs based on relevant research findings in the field of education and second/foreign language learning.. Autonomy. According to self-determination theory, autonomy is one of the three major factors promoting intrinsic motivation or more self-regulated forms of extrinsic motivation. Deci and Ryan (1985) proposed that when people feel free from pressure and control, like rewards and punishment, intrinsic motivation can truly function to initiate autonomous 24.

(39) behaviors. In general education, autonomy is characterized by being able to learn actively and independently (Wang & Peverly, 1986). In applied linguistics, Holec (1981) has a similar view on autonomy that learners can take responsibility for their own learning by deciding individual learning objectives, materials and the way in which their learning would proceed. Oxford and Shearin (1994) especially emphasized the importance of goal setting in second language learning motivation. They addressed that goals could function as effective motivators if they are specific, attainable, accepted by students and combined with positive and informative feedback concerning learning progress. Conclusively, an. 政 治 大 what they need, formulating appropriate learning goals, deciding suitable materials and 立. ideal autonomous learner often demonstrate the following learning traits: being aware of. ways to learn, initiating independent learning behaviors, adjusting their original goals,. ‧ 國. 學. monitoring their learning process and evaluating their learning outcomes.. ‧. Moreover, autonomous learners tend to attribute their learning success or failure to. sit. y. Nat. effort rather than other uncontrollable reasons, like ability or luck; therefore, they are. io. er. likely to persist in their learning when encountering obstacles (Child, 1994). This characteristic indicates that autonomous learners obtain greater control over their learning. al. n. v i n than those who don’t view theirC success or failure as the h e n g c h i U result of their effort. Dornyei (1990) further pinpointed that foreign language learners often have plenty of failure experiences; thus, failure attributions are especially important in foreign language learning environment.. Besides the learning traits identified from autonomous learners, teachers also play an important role in promoting students’ autonomy. Much research has proved that autonomy-supportive teachers could help students cultivate their autonomous motivation (Assor, Kaplan, Kanat-Maymon, & Roth, 2005; Guay, Boggiano, & Vallerand, 2001; Noels, Clement, & Pelletier, 1999; Reeve & Jane, 2006) and attain better achievement outcomes (Jane, 2008; Soenens & Vansteenkiste, 2005; Vansteekiste et al., 2005). Several 25.

(40) studies have found that teachers’ communication style, such as the ways of presenting learning tasks, could influence students’ learning motivation (Dornyei, 1994; Williams & Burden, 1997). Deci et al. (1991) advised that teachers’ manners (the style or language) of presenting external events, like feedback, grades, rewards, performance evaluation should be autonomous-supportive. By doing so, those external events can function as motivational techniques that help develop students’ autonomy. Furthermore, they also encouraged teachers to become more autonomous-supportive rather than controlling by ―offering choice, minimizing controls, acknowledging feelings, and making available. 政 治 大 et al., 1991, p. 342). Reeve and Jane (2006) identified a number of autonomy-supportive 立. information that is needed for decision making and for performing the target task‖ (Deci. teacher behaviors which were found correlated with students’ autonomous motivation in. ‧ 國. 學. classroom settings. They were listening to students, asking students what they need,. ‧. giving time for students to learn in their own way, providing opportunities for students to. sit. y. Nat. talk, notifying students of the rationales behind classroom activities, instructions and. io. er. suggestions, offering positive informative feedback to acknowledge students’ progress and encourage students’ effort, giving cues to students in need when they encounter. al. n. v i n difficulties, being responsive to C students’ feedback andUquestions, and understanding hengchi. students’ personal perspectives and feelings. In short, with teacher’s autonomy support, students could enhance their self-determination and intrinsic motivation, encourage persistence in learning and even facilitate achievement (Deci & Ryan, 1985, Deci et al., 1991). In sum, by developing learners’ autonomous learning traits and providing learners an autonomous learning environment with teachers’ support, the goal of promoting their intrinsic motivation or more self-determined forms of extrinsic motivation to learn is more likely to be realized.. 26.

(41) Competence. Regarding the definition of competence in self-determination theory, the need for competence involves being aware of the ways to attain the outcomes and also being efficacious in carrying out necessary actions to achieve them (Deci et al., 1991). In order to satisfy learners’ need for competence and promote intrinsic motivation, it is important to provide them with the opportunities to perceive their own competence (Harter & Connell, 1984). Deci and Ryan (1985) suggested two possible ways that may contribute to individual perceived competence. They are providing positive informative feedback. 政 治 大 Feedback from teachers or peers has certain effect on students’ learning motivation. 立. and accumulating success experiences.. Generally, positive feedback is more preferable (Vallerand & Reid, 1988). If learners are. ‧ 國. 學. immersed in the positive feedback about their learning behaviors or the praises that. ‧. attribute success to effort, their self-regulated motivation for learning would be developed. sit. y. Nat. gradually. In addition, they may value and enjoy their learning more and maintain their. io. er. momentum to learn even though there is no such feedback as reinforcement. Ryan (1982) also had similar findings that positive feedback administered in an autonomous way could. al. n. v i n C h maintain self-initiated help learners perceive their competence, learning behavior and thus engchi U. increase learner’s intrinsic motivation.. On the contrary, controlling feedback pertinent to social comparison is harmful to intrinsic motivation (Ames, 1992). It’s because such feedback often turns students’ attention from learning to competing with their classmates and peers, which often undermines students’ interest in learning itself. Therefore, it’s important to ensure positive feedback is given to acclaim and affirm learner’s self-initiated effort and the competence gained from the effort, so that learners can value their learning and simultaneously become motivated to learn.. 27.

(42) In terms of gaining success experience, Hunt (1966) suggested that optimal-challenging tasks, which are not overly difficult or easy to students, could help students generate interest and the feelings of competence, either of which is beneficial in promoting intrinsic or more self-regulated motivation. It may be due to that humans have a natural tendency to enjoy and get immersed in optimal challenges, and thus through the process of overcoming the challenges, their competence is developed as well (Elliot et al., 2000). Deci and Ryan (1985) also agreed to the employment of optimal challenges in learning contexts for students could perceive their competence from their success. 政 治 大 (1994) also gave the same suggestion that teachers could provide more attainable and 立. experiences in challenging but achievable tasks. In language learning, Oxford and Shearin. meaningful language tasks for students to experience success regularly so that their sense. ‧ 國. 學. of self-efficacy could be built up. In short, assisting students in recognizing their own. ‧. competence through positive autonomy-supportive feedback and optimal-challenging. sit. y. Nat. tasks can offer support for their competence needs and thus promote their intrinsic or. io. n. al. er. more self-determined motivation.. Relatedness.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Relatedness is the third inherent need that contributes to the development of more self-regulated or intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985). It refers to the secure and satisfactory interpersonal involvement and social interaction with others in the society. When it comes to second and foreign language learning environments, relatedness usually involves the relationship with teachers and classmates. Gardner (1985) pointed out that students’ attitudes toward their teachers may affect their motivation to learn and their learning results. It may be due to that students would engage in academic tasks more if their relationship with teachers is positive and secure, meaning that they feel being liked, understood, and helped when they are in need by their teachers (Skinner & Belmont, 28.

數據

+6

相關文件

透過適切的活動提升閱讀深度及加強學習連 貫性 —— 優化中一單元中華文化及品德情意 範疇的學習內容

課題 感動一刻 學習階段 第三學習階段 科目 視覺藝術 ..

學習範疇 主要學習成果 級別 級別描述 學習成果. 根據學生的認知發展、學習模式及科本

二、 學 與教: 第二語言學習理論、學習難點及學與教策略 三、 教材:. 運用第二語言學習架構的教學單元系列

Rebecca Oxford (1990) 將語言學習策略分為兩大類:直接性 學習策略 (directed language learning strategies) 及間接性學 習策略 (in-directed

新角色 新角色 新角色 新角色: : : : 學習促進者 學習促進者 學習促進者 學習促進者 提供參與機會 提供參與機會 提供參與機會 提供參與機會 引導而不操控

貼近學生生活 增加學習興趣 善用應用機會 提升表達能力 借用同儕協作 提升學習動機 豐富學習經歷

學生平均分班,非 華語學生與本地學 生共同學習主流中 文課程,參與所有 學習活動,並安排 本地學生與非華語 學生作鄰座,互相