傷害性產品的善因行銷研究 -產品與善因之間的關連性和產品類別之影響

116

0

0

全文

(2) 謝 辭 歷經一整年,從研究主題的構思、架構、問卷設計到看到自己的研究結果出 爐,之中的辛苦都在最終完成整篇論文那一刻化成了無限的感動。首先要先感謝 我的指導教授張純端老師,在研究的過程中不斷地給予指導跟提供不同的想法與 建議,老師就像楷模一般,從她身上讓我學習到作研究應有的嚴謹態度,以及對 各項細節的要求,這些寶貴的學習經驗都讓我獲益匪淺,再次感謝張老師的指 導,這些充實的訓練過程,相信我ㄧ輩子都受用無窮,也讓我更珍惜這張碩士文 憑。. 而在兩年的研究所生涯,從不適應到慢慢摸索出方向,一路上好多人給我鼓 勵跟支持,首先,先感謝我爸爸,要不是有他的督促,我也不會有今天;而我媽 媽在我最失落的時候,支持者我、鼓勵我;我妹妹,幫我想修辭文法和做問卷; 明明,真的很感謝你,總是聽我訴苦,給我許多安慰和實質上的幫助,讓我有繼 續下去的動力;百立,想到你就讓我很開心;佳靜、秀韻,還有我的研究所同學, 謝謝你們在我研究時遇到瓶頸,願意花時間幫我想以及給我許多建議。Pearl、 Paul、Allen,在我英文寫作上給了我極大的幫助。最後再次感謝大家,有你們 真好,謝謝。.

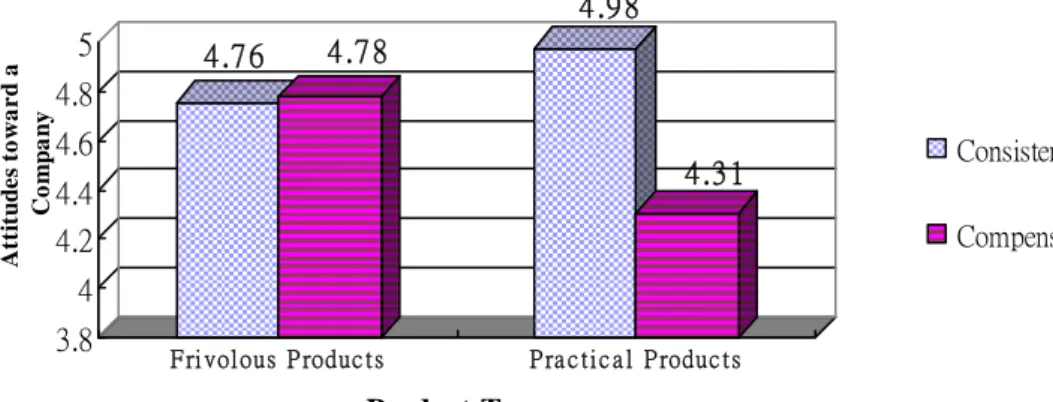

(3) Does Product-Cause Fit Really Matter in Cause-Related Marketing for Harmful Products? Influences of Fit Nature and Product Type Student: Chia-Ying Lee Institute of Economics and Management National University of Kaohsiung Advisor: Dr. Chun-Tuan Chang Department of Business Management National Sun Yat-sen University. ABSTRACT. Cause-related marketing (CRM) is a philanthropic strategy in which a corporation donates money to a charity each time a consumer purchases a specific product. One important variable that has been identified to increase the success of CRM is the fit between the product and the cause. However, little is known how to associate with the appropriate cause to be a good fit link for increasing CRM effectiveness. In a present study, two high-fit strategies were examined: consistency fit (i.e., a cause and a product have consistent images or similar values) and compensation fit (i.e., a selected cause is used to improve a harmful image of the product through a compensation act). Deciding upon the best fit to employ is especially important for marketers in situations when consumers perceive the product as harmful and thus already have negative perceptions. Regarding these harmful products, this research elaborates on the concept of product-cause fit by examining how consumer perceptions of fit nature affect attitudes toward the sponsoring company and purchase intention in purchase situations with different product types (i.e., practical or frivolous products). The results indicate that consumer attitudes toward a sponsoring company are evaluated more favorable when the chosen cause is based on consistency fit rather than compensation fit. More interestingly, when promoting frivolous products, the consistency fit and the compensation fit strategies have similar effects on CRM effectiveness. When the product nature is perceived as practical, the consistency fit between the product and the cause is more effective in promoting CRM. Keywords: Cause-related marketing (CRM), harmful products, product-cause fit, product type, CRM advertising effectiveness. 3.

(4) 傷害性產品的善因行銷研究 -產品與善因之間的關連性和產品類別之影響 學生:李佳穎 國立高雄大學經濟管理研究所 指導教授: 張純端 博士 國立中山大學企業管理學系. 摘要 善因行銷(Cause-related Marketing;CRM)是ㄧ種結合慈善的行銷策略,其活動方式 大致是企業承諾在消費者購買該公司的產品或服務後,便捐出一定金額給某非營利機構從 事特定的慈善活動。過去的研究指出產品和善因之間的“關聯性"越高,會使善因行銷更 加的成功。然而,企業如何去選擇合適的善因形成一個良好的關聯性,仍然是過去研究較 少著墨的。此篇研究定義出兩種不同“高度關聯性"的策略:ㄧ致性(善因和產品之間是有 一致的形象或者是相似的價值觀)和補償性(所選擇的善因是用來改善傷害性產品的形 象)。而對行銷企劃者而言,選擇一個最有效的善因行銷策略對原先就具有負面形象的傷害 性產品尤其重要。因此,此篇研究針對傷害性產品,考量不同的產品類別(例如;實用性或 者是享樂性)去檢驗不同的關連性策略對公司的觀感和購買意願的影響。研究結果指出一致 性的策略是比補償性的策略更能獲得消費者的好感。有趣的是,當善因廣告促銷享樂性產 品的時候,使用一致性的策略所得到的廣告效果與使用補償性的策略所得到的廣告效果是 相似的,但當產品類別是屬於實用性的時候,一致性的策略是比補償性的策略能更能提升 消費者對採用善因行銷公司的態度。. 關鍵詞:善因行銷、傷害性產品、產品與善因之間的合適性、產品類別、善因行銷的廣告 效果. 4.

(5) Table of Contents CHAPTER ONE AN INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................8 1.1 Preamble .....................................................................................................................8 1.2 Research Background and Motives..........................................................................8 1.2 Research Objectives and Research Questions....................................................... 11 1.3 Structure of the Thesis.............................................................................................12 CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW .......................................................................14 2.1 Preamble ...................................................................................................................14 2.2 Introduction to Cause-Related Marketing (CRM) ...............................................14 2.3 Influences of Product-cause Fit on CRM Effectiveness .......................................16 2.4 Influences of Product Type on CRM Effectiveness ..............................................18 2.5 Influences of Consumer Inferred Motives on CRM Effectiveness ......................20 2.6 Concluding Remarks ...............................................................................................22 CHAPTER THREE RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHOD...........................................24 3.1 Preamble ...................................................................................................................24 3.2 Hypotheses ................................................................................................................25 3.2.1 Influences of Product Type on CRM Effectiveness ...................................26 3.2.2 Influences of Product-Cause Fit on CRM Effectiveness ...........................26 3.2.3 Relationship between Product Type and Product-Cause Fit on CRM Effectiveness ...........................................................................................................28 3.3 Method ......................................................................................................................32 3.3.1 Research Design and Pretest........................................................................32 3.3.1.1 Overview of the Pretest .....................................................................33 3.3.1.2 Pretest Results ....................................................................................33 3.3.2 Experimental Design.....................................................................................35 3.3.2.1 Overview .............................................................................................35 3.3.2.2 Participants.........................................................................................36 3.3.2.3 Research Variables.............................................................................36 3.3.2.3.1 Independent Variables and Manipulation............................36 3.3.2.3.2 Dependent Variables...............................................................37 3.3.2.3.3 Possible Covariates of Individual Differences on CRM Effectiveness ...........................................................................................37 3.3.2.4 Questionnaire and Advertisements ..................................................38 3.3.2.5 Administration Procedure.................................................................41 3.4 Concluding Remarks ...............................................................................................42 5.

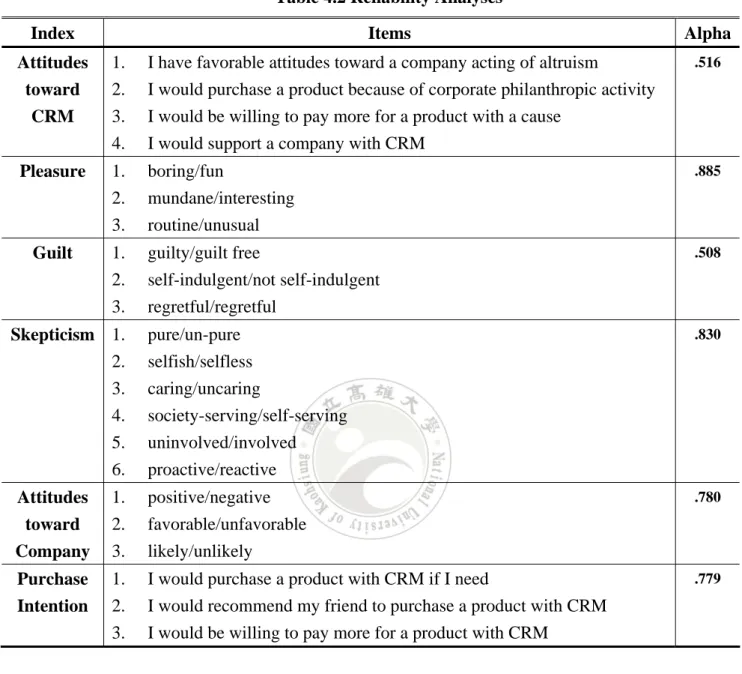

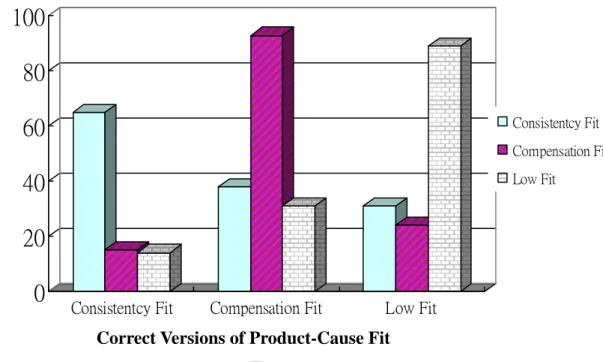

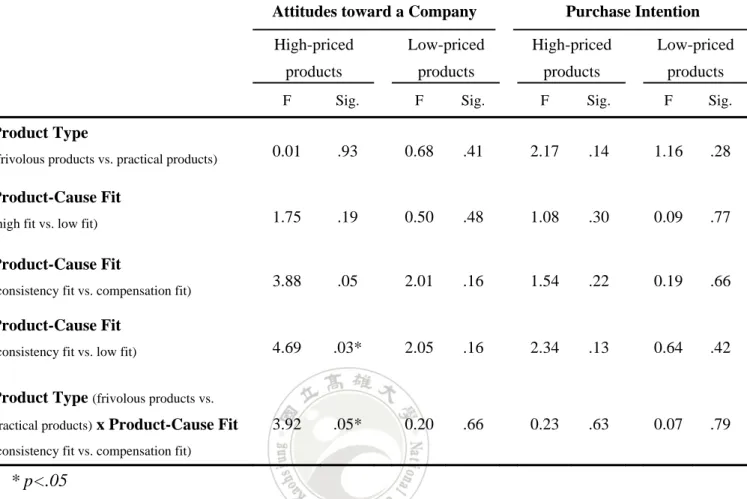

(6) CHAPTER FOUR DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS ......................................................43 4.1 Preamble ...................................................................................................................43 4.2 Background Information.........................................................................................43 4.3 Reliability of Measures ............................................................................................44 4.4 Checking the Design ................................................................................................45 4.4.1 Manipulation Check on Product Type........................................................45 4.4.2 Manipulation Check on Product-Cause Fit................................................46 4.4.3 Check for Possible Covariates of Individual Differences ..........................47 4.5 Preliminary Analyses...............................................................................................48 4.5.1 Influences of Pleasure with Purchase on Consumer Behavior .................48 4.5.2 Influences of Guilt with Purchase on Consumer Behavior.......................48 4.6 Hypotheses Testing ..................................................................................................48 4.6.1 Overview of the Results ................................................................................48 4.6.2 Results of High-Priced Products and Low-Priced Products.....................51 4.6.3 Influences of Consumer Skepticism on CRM Effectiveness .....................54 4.7 Concluding Remarks ...............................................................................................55 CHAPTER FIVE CONCLUSIONS ....................................................................................56 5.1 Preamble ...................................................................................................................56 5.2 Discussion on the Findings ......................................................................................56 5.3 Limitations of Research...........................................................................................60 5.3.1 Experimental Design.....................................................................................60 5.3.2 Student Sample..............................................................................................60 5.3.3 Environmental Issues ...................................................................................61 5.4 Contributions of the Study......................................................................................61 5.4.1 Theoretical Contributions ............................................................................61 5.4.2 Managerial Contributions............................................................................62 5.5 Proposals for Future Research ...............................................................................63 5.5.1 Categorization of Product Type ..................................................................63 5.5.2 The Extension of Product-Cause Fit ...........................................................63 5.5.3 Influence of Price on CRM Effectiveness ...................................................64 5.5.4 Influence of Individual Differences on CRM Effectiveness ......................65 5.6 Conclusions...............................................................................................................65 REFERENCES .......................................................................................................................67 APPENDIX .............................................................................................................................74 Appendix A. Pretest of Questionnaire..........................................................................75 Appendix B. Twelve Versions of Questionnaire ..........................................................76 6.

(7) List of Figures Figure 3.1 The Stages of Research................................................................................25 Figure 3.2 The Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses...........................................32 Figure 3.3 Consumer Perception of the Causes in Pretest .........................................34 Figure 3.4 Examples of the Copies of Advertisement in the Experiment .................40 Figure 4.1 Participants’ Perception of Product-Cause Fit .........................................47 Figure 4.2 CRM Effectiveness between Product Type and Product-Cause Fit........53. List of Tables Table 3.1 Manipulation of Messages of CRM Advertisement....................................41 Table 4.1 Demographic Data for the Sample ..............................................................44 Table 4.2 Reliability Analyses.......................................................................................45 Table 4.3 A Summary of Statistical Tests....................................................................49 Table 4.4 Means and Standard Deviations of Participants’ Attitudes toward a Company and Purchase Intention................................................................................49 Table 4.5 A Summary of Statistical Tests for High and Low Price ..........................52 Table 4.6 Summary Table for the Results of Hypotheses Testing.............................54. 7.

(8) CHAPTER ONE AN INTRODUCTION. 1.1 Preamble One important variable that has been identified to increase the success of cause-related marketing (CRM) is fit between the product and the cause. This research elaborates on the concept of product-cause fit by examining how consumer perceptions of fit nature affect attitudes toward the sponsoring company and purchase intention in purchase situations with different product types (i.e., practical or frivolous products). Especially, it focuses on how a company chooses an appropriate cause to constitute a good fit when consumers perceive the products as harmful. Deciding upon the best fit to employ is especially important in situations where consumers already have inherent negative perceptions of those harmful products. Additionally, the interaction effect between the product-cause fit and product type on consumer preference is investigated.. 1.2 Research Background and Motives Corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives have become prominent and increasingly popular in recent years. Previous studies find that consumers are more favorable toward new products from companies that are perceived to be socially responsible (Brown & Dacin, 1997) and evaluate those companies more positively (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001) As a result, an increasing number of companies have developed CSR programs and tied CSR activities closely to their operations in pursuit of building a positive corporate image and enhancing sales (Maignan & Ralston, 2002). By the growth of dedicated CSR organizations worldwide, socially responsible corporate activities may represent an important source of competitive advantage as it can enhance and raise the overall reputation of a company. As a variety of socially responsible business activities have emerged, corporations are 8.

(9) reconsidering how community involvement and CSR can be tied to achieve their business objectives. Under this circumstance, corporations start to partner with non-profit organizations in creative ways to achieve their goals. Therefore, CRM is progressive outgrowth of this trend as an increasingly common form of CSR initiatives. With regard to CRM, it involves a company’s promise to donate a certain amount of money to a nonprofit organization or a social cause each time a customer makes a purchase for its products or service (Xiaoli & Kwangjun, 2007). Moreover, currently managers are facing increasing pressure to their philanthropic activities to take strategies to improve bottom-line performance and enhance their competitive advantage (Andreasen, 1996; Varadarajan & Menon, 1988). CRM has become a major corporate philanthropic activity based on the rationale of profit-motivated giving that can be viewed as a manifestation of the alignment of corporate philanthropy and benefit business (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988). As CRM becomes more important and common form of marketing strategy in the marketplace, researchers have begun to investigate the potential factors that might influence the effectiveness of CRM. One important variable that has been identified to increase the success of CRM is the fit between the product and the cause (Benezra, 1996; Olsen & Pracejus & Olsen, 2004; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). In Pracejus and Olsen studies, they find that consumers are willing to pay more for products or services when the relationship of product-cause is perceived as a high fit than the one is perceived as a low fit. Although there are an amount of discussion about fit and researchers agree that choosing the “fit” cause is important to facilitate CRM successful, little is known about what constitutes a good fit and how the nature of fit can be used to increase CRM effectiveness. In particular, there are many different products characterized in the marketplace. Some of the products in regard to material, contains or the process of producing might cause the negative influence on environment or human health. For example, fast food usually contains high in cholesterol, fat, salt and sugar. According to a large multi-center study funded by the 9.

(10) National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), after 15 years those who ate at fast-food restaurants more than twice each week had gained an extra ten pounds and a risk factor for diabetes and heart disease, which could be viewed as one of the harmful products to cause obesity and detrimental health. On the other hand, people are becoming increasingly aware of links between environmental problems of water and air pollution, land degradation, chemical contamination, and over-consumption (e.g., clothing, food, housing, and transport) (Esther & Ricky, 1998). Those products result in creating environmental problems through their distribution cycle and package material, which could be seen as some of harmful products. Deciding upon the best fit to employ is especially important in situations where consumers already have negative perceptions toward these harmful products. In terms of CRM activities, McDonald’s launched a campaign for giving children a chance at happier and healthier lives in 2007. From November 9th to 11th McDonald’s donated $1 to Ronald McDonald House Charities, Inc. (RMHC) from the sales of any Chicken McNuggets Extra Value Meal and Beef and Chicken sandwich Extra Value Meal to create, find and support programs that directly improve the health and well being of children. Meanwhile, McDonald’s support charities not only about choosing children initiatives but also about sponsoring some human health foundation like American Heart Association (AHA). In 2005 McDonald's donated $7 million to the AHA to be used for public education regarding health effects of trans-fat and encouraging substitutions, which could be interpreted that McDonald's attempt to do something good through a compensation act for the harm from their products. Based on these real examples in the marketplace, both the relationship between McDonald’s and children initiatives, and that between McDonald’s and health issues could be viewed as different types of high fit. Research to date has also indicated product types could be viewed as the other important factor to influence the effectiveness of CRM. Different types of products may evoke different emotional states in regards to consumption. These emotional states determine the 10.

(11) effectiveness that a charity incentive will have in promoting a product (Ahtola, 1985; Babbin, Darden & Griffin, 1994; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Strahilevitz, 1999; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). However, when promoting the different product types with harmful nature, researchers have not fully addressed how to associate with the appropriate cause to be a good fit link for improving the company’s negative image and increasing the sales revenue. This study tries to identify these two factors that are worth considering in the course of such a CRM process. .. 1.2 Research Objectives and Research Questions In a present study, influences of product-cause fit and product type on CRM effectiveness will be focused. The purpose of this study is to investigate which type of product-cause fit presented is most likely to be effective in CRM. Deciding upon the best fit to employ is especially important in situations when consumers perceive the product as harmful and thus already have inherent negative perceptions. Regarding these harmful products, the concept of fit can be extended diversely with multiple cognitive bases. Thus, there are two high-fit relationship examined: consistency fit (i.e., a cause and a product have consistent images or similar values) and compensation fit (i.e., a selected cause is used to improve a harmful image of the product through a compensation act). This research also examines the effects of the hedonic and utilitarian nature of the products promoted on CRM effectiveness when consumers purchase the products as harmful. More specifically, this research elaborates on the concept of product-cause fit by examining how consumer perceptions of fit nature affect attitudes toward the sponsoring company, and purchase intention in purchase situations with different product types. Based on the aforementioned objectives, this research seeks to examine the influences of product-cause fit and product type in harmful product contexts and address the specific sets of questions as follows: 11.

(12) 1.. Product type effects: Will product type influence CRM effectiveness when consumers make a decision for purchasing a harmful product?. 2.. Product-cause fit effects: In terms of harmful products, does high fit between the product and the cause matter? What type of product-cause fit (i.e., consistency fit vs. compensation fit) can improve the company’s image of the harmful products and affect the consumers’ willingness to purchase the sponsored products?. 3.. Relationship between product type and product-cause fit: When different product types are considered, will effectiveness of compensation fit and consistency fit differ? These research issues above are important to answer and understand because they. contribute to the growing literature of cause-related marketing by assessing the impacts of (1) frivolous products (vs. practical products) on CRM effectiveness, when consumers perceive the products as harmful, (2) high fit (vs. low fit) affecting CRM effectiveness when promoting the harmful products, (3) compensation fit (vs. consistency fit) affecting CRM effectiveness when promoting the harmful products, (4) how the nature of product type and product-cause fit interact to determine the effectiveness that a charity incentive will have when promoting the harmful products. This research is developed to test the relative CRM effectiveness of advertisement messages to promote products that consumers perceive to be harmful. Thus, in practice, marketers stand to gain not only by choosing the appropriate fit cause for their advertised products, but also by taking the perceived product nature of the offered bundles into consideration.. 1.3 Structure of the Thesis This chapter provided an introduction to CRM and presented the justification as to the need for research in this emerging area. Chapter Two will outline the theoretical foundations that underpin this research study. Fist, a review of CRM literature will be presented within 12.

(13) the context of the marketing communications discipline. In addition, relevant literature from the areas of product-cause fit, product type, and influence of perceived company motivation will be also identified. Chapter Three will outline hypotheses that were developed from the literature in Chapter Two and the method for testing the model. It also will discusse the research design, treatment of variables, details of the sample data collection and data analysis methods. Then, the results of the hypothesis testing will be presented in Chapter Four. The last chapter (Chapter Five) will discuss the conclusions and implications of the findings as well as theoretical and managerial contributions of this research. Limitations of these findings will be identified and suggestions for future research will be also proposed.. 13.

(14) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW. 2.1 Preamble This chapter begins by introducing relevant CRM research and effectiveness in current practice and how consumers to respond CRM, and then focuses on the various concepts of fit in marketing strategy and its influence on CRM. In addition, it discusses the nature of product types between two types of consumption based on a review of the related literature and outlines variables contained in CRM. The relevant research on the influences of consumer motivation on CRM is also discussed. The final section summarizes these findings and their importance, and offers the theoretical basis for the present research.. 2.2 Introduction to Cause-Related Marketing (CRM) As the corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives have become increasingly popular, an increasing number of companies have developed CSR programs (Maignan & Ralston, 2002). Traditionally, the underlying purposes of CSR activities were recognized as being purely altruistic. Owners would set aside a portion of their firm’s profits for charitable causes. However, corporations have come to seek profit maximization as a goal within a socially justifiable context. Altruistic intensions alone can no longer justify charitable giving and expenditures related to philanthropic activities (Kim, Kim & Han, 2005). The practice of advocating CSR in marketing communications activities is commonly known as CRM. The first publicized CRM campaign is led by American Express in 1983 for the Statue of Liberty Restoration project. The American Express promised to contribute one cent for every card transaction and $1 for every new card issued. American Express not only collected $1.7 million but there was a 28 percent increase in use of their credit cards, not to mention massive press coverage and free publicity. While profits of $1.7 million, from increased use of. 14.

(15) American Express cards, were donated to the organization, American Express called its link with charity “cause related marketing” and registered the term as a service mark with the U.S. Patent Office (Smith & Higgins, 2000). According to the IEG Sponsorship Report, Chicago, cause marketing sponsorship by American businesses is rising at a dramatic rate. US Sponsorship were spending $1.17 billion $1.34 billion on CRM in 2006, and so far the number was to rise further to hit $1.44 billion in 2007. Back in 1990, cause sponsorship spending was only $120 million. The total annual sum has now passed the one billion dollar mark. In light of the growing popularity and large investments in CRM programs by firms, CRM has became a powerful marketing tool that business and nonprofit organizations are increasingly devoting to. As CRM becomes rather popular promotion strategy for companies, this prevalence draws research attention from industry to academia. In the previous literature, Varadarajan & Menon (1988) offer one of the comprehensive conceptualization of CRM. They define CRM as “the process of formulating and implementing marketing activities that are characterized by an offer from the firm to contribute a specified amount to a designated cause when customers engage in revenue-providing exchanges that satisfy organizational and individual objectives”. Besides, CRM is a form of corporate philanthropy based on the rationale of profit-motivated giving that can be viewed as a manifestation of the alignment of corporate philanthropy and enlightened business. In practice, CRM is also a strategy for a company designed to achieve business objectives through support of a cause or charity. In conclusion, CRM is a merging of self-interest and altruism, marketing, and philanthropy (Daw, 2006). The increasing strategic importance of consumer relevance of such socially responsible marketing initiatives is also evidenced in the results of a Cone and Roper consumer survey. According to the Cone Millennial Cause latest study (2006), consumers report that when given a buy choice between two products of equivalent price and quality, 74% are more likely to pay attention to a company’s message when they see that the company has a deep 15.

(16) commitment to a cause. 89% of Americans, ages 13 – 25, stated they would switch from one brand to another brand of a comparable product and price if the latter brand was associated with "a good cause". In addition, the growing body of experimental studies shows that consumers tend to have favorable attitudes toward companies, which support a cause, and these attitudes are likely to positively influence product evaluation and purchase decisions (Barone et al., 2000; Brown & Dacin, 1997). Thus, CRM is seen as a way for a company to establish long-term differentiation from competitors and to add value to the corporate brand (Davidson, 1997), which all gives the company a competitive advantage (Murphy, 1997). Through CRM, corporations and non-profits often work closely together to achieve mutually beneficial results. CRM has taken the relationships betweens corporations and non-profits to a new level (Brown & Dacin, 1997). 2.3 Influences of Product-cause Fit on CRM Effectiveness Fit could be found in various research streams in marketing such as brand extensions, co-marketing alliances, sponsorships, and brand alliance, which indicate that perceived fit generally leads to a positive effect on attitudes (Aaker & Keller, 1990; Bucklin & Sengupta, 1993; Rifon, Choi, Trimble, & Li, 2004; Simonin & Ruth, 1998). The sales literature on person-organization fit suggests that employees prefer to work for companies that are compatible with their personalities (Pappas & Flaherty, 2006). On the brand literature, Park, Jun, & Shocker (1996) find that when the two brands in the composite have greater fit in terms of attribute complementary, success is facilitated. Also for celebrity endorsers, increased spokesperson-product fit results in a more favorable product attitude (Kamins & Gupta, 1994). Similarly, a significant number of sources within the CRM literature address the issue of ‘fit’ between the cause and the company/brand/product. Generally speaking, fit is viewed as the perceived link between the company’s image, positioning and target market and the. 16.

(17) cause’s image and constituency (Ellen, Mohr, & Webb, 2000; Varadarajan & Menon, 1988). In CRM brand-cause fit can also originate from multiple sources. A brand could fit with a social cause if both server a similar consumer base (e.g., the General Mills campaign that ties Yopliait and the fight against breast cancer). In addition, fit could be high if a brand and social cause share a similar value (Xiaoli & Kwangjun, 2007). The research on fit between the product and the cause is either all about based on common values or logical connection. However, sometimes it is only about making sense (Lafferty, 2007). According to pervious research, Berger, Cunningham, and Drumwright (2004) consider even nine dimensions of fit that can contribute to success. Focused on the product-cause fit, Drumwright (1996) take it into two forms to explain. The first is co-branding through which the association of the nonprofit’s name with the company’s name can be construed as a meaningful implied endorsement. The other involves a compatible positioning between the company and the cause that is based on an element of strategic similarity, such as a company with a reputation for providing international merchandise and an international cause. Fit is a key to the success of product-cause alliance campaign (Benezra, 1996) and has been proved the influence across all the domains above. Fit has generally been found to facilitate transfer of positive from an object to the object-associated brand. Congruence theory is one of the theories used to support the effects of fit and explain this phenomenon and why fit is so important. It suggests that storage and retrieval of information from memory are influenced by relatedness or similarity. The more congruent, the better the association and retrieval. Based on this point of view, the researchers recommend that the company, brand or product should have a ‘good fit’ with the cause that they hope to form an association with (Gray, 2000; Murphy, 1997; Welsh, 1999). In addition, having a ‘good fit’ allows companies to optimize the performance of their CRM initiatives (Hamlin & Wilson, 2004). For example, Pracejus and Olsen (2004) find that donation to a high-fit charity can result in 5-10 times the value of donation to a low-fit charity, which suggests that fit can result in great returns in 17.

(18) CRM. Gupta and Pirsch (2006) demonstrate that company-cause fit improves attitude toward the company-cause alliance and increases purchase intention. This effect is enhanced under conditions of customer-company and customer-cause congruence, and the consumer’s overall attitude toward the sponsoring company.. 2.4 Influences of Product Type on CRM Effectiveness One major factor examined in CRM during the past few years is product type (Strahilevitz, 1999; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). The product type being promoted can influence the effectiveness of CRM. Previous work has indicated that the affective nature of many everyday consumption experiences could be different (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982). These researchers pay attention to a distinction between two types of common products when consumed and define them as follows: 1. Hedonic, pleasure-oriented consumption is motivated mainly by the desire for sensual pleasure, fantasy and fun (e.g., the consumption of a hot fudge sundae or spending a week sunning in Hawaii). Such products are often labeled “frivolous” or “decadent”. 2. Utilitarian, goal-oriented consumption is motivated mainly by the desire to fill a basics need or accomplish a functional task (e.g., the consumption of a bottle of dishwashing liquid or a box of trash bags). Such products are often labeled as “practical” or “necessary”.. Both hedonic and utilitarian goods offer benefits to the consumer. A similar but different pair of constructs to hedonism and utilitarianism is the “wants” and “shoulds” (Bazerman, Tenbrunsel, & Wade-Benzoni, 1998). The wants are more affectively and experientially appealing than the shoulds, just as hedonic alternatives are more affectively and experientially appealing than utilitarian ones. These two types of products evoke quite different affective states in the circumstance of consumption (Ahtola, 1985; Babbin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994; Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Strahilevitz, 1999; Strahilevitz & Myers, 18.

(19) 1998). For example, the feelings associated with purchasing utilitarian or practical items, such as toilet paper, laundry detergent, or vacuum cleaners may not be the same as the feelings associated with purchasing more hedonic or frivolous items, such as chocolate truffles, expensive cologne, or ice cream. A distinction has been made between two types of consumption that differ in terms of their affective content and which are driven by quite different motives (Strahilevitz, 1999; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). In particular, hedonic consumption is often construed as wasteful (Lascu, 1991). Because of this difference, there is a sense of guilt associated with hedonic consumption. Pervious researches indicate guilt as a negative affect that a person may wish to relieve by engaging in charitable activities (Cialdini, Kenrick, & Baumann, 1982; Kivetz & Simonson, 2002a, 2002b; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). Furthermore, Strahilevitz and Myers suggest that altruistic incentives could be viewed as a more effective way to reduce the sense of guilt when the products perceived as pleasure-oriented and frivolous than the products perceived as goal-oriented and practical. The explanation given for this effect shows that experiencing either pleasure (Cunningham, 1979; Isen, Shalker, & Lynn, 1978; Levin & Isen, 1975) or guilt can significantly increase an individual’s tendency to engage in charitable behavior (Ghingold, 1981). Strahilevitz and Myers (1998) explain this phenomenon as affect-based complementarity since the feelings generated by hedonic products appear to complement the feelings generated from contribution to charity than with the more functional motivations associated with practical products. Therefore, bundling a hedonic purchase with a promised contribution to charity could reduce the sense of guilt and thus facilitates hedonic purchases (Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). People try to construct reasons for justification when consumed (Shafir, Simonson, & Tversky 1993), and quantifiable reasons are easier to justify (Hsee, 1996; Shafir, Simonson, & Tversky 1993). Conceptually, utilitarian goods tend to be relative necessary and hedonic goods tend to be relatively discretionary (Okada, 2004). Therefore, it is easier to construct 19.

(20) justifiable reasons for utilitarian consumption than for hedonic consumption. The explanation is that hedonic goods deliver benefits primarily in the form of experiential enjoyment, which may be more difficult to evaluate and quantify than the practical, functional benefits that utilitarian goods deliver. In addition, perceived utilitarian shopping value might depend on whether the particular consumption need stimulating the shopping trip was accomplished. Thus, a utilitarian product is purchased in a deliberant and efficient manner (Babbin, Darden, & Griffin, 1994) and utilitarian consumer behavior has been described as task-related and rational (Batra & Ahtola 1991).. 2.5 Influences of Consumer Inferred Motives on CRM Effectiveness CRM is an emergent body of literature suggesting a positive correlation to exist between CRM and possible future business success. Supporting socially responsible activities can positively affect not only consumers’ purchasing motivation but also their overall evaluation of a company (Sen & Bhattacharya, 2001). Consumers may perceive it as important for companies to become good corporate citizens, and may have a more positive image of a company, if firms wish to be perceived as doing something good to make the world better. However, CRM activity may not contribute to the desired intention of achieving positive effects (Strahilevitz, 2003; Szykman, 2004; Webb & Mohr, 1998). Researchers find that a firm's perceived support of social causes may influence consumer choices, but simple financial support is never quite enough in the long run. Marketers must learn to consider how consumers come to perceive a company's motivation (Barone, Miyazaki, & Taylor 2000). This is especially true whenever consumers start to focus on their funding of specific CRM programs, rather than on general CRM programs. Initial consumer attribution of a company’s possible motives for conducting CRM programs may influence how they respond to those programs (Kim, Kim & Han 2005). Among all aspects of consumer motivation, a few studies indicate that distrust and 20.

(21) skepticism towards a company affect the possible successful outcome of how CRM activity is to be evaluated. Thus, identification of factors and processes which lead consumers to become skeptical as to a company’s real motives (i.e., the perceived intentions behind the actual practice of CRM activities) becomes a critical issue. Consumer skepticism is often determined by whether or not the CRM programs are perceived as cause-beneficial, or as cause-exploitative (Varadarajan & Menon, 1988). Skepticism has been defined as a person’s tendency towards showing disbelief (Obermiller & Spangenberg, 2001). Webb and Mohr (1998) describe skepticism as one of two logical constructs used to explain possible human reactions to the communications they receive, or to how more situational experiences may not be as long lasting. Kanter & Mirvis (1989) point out that “skeptics doubt the substance of communications”, and a highly skeptical people perceive the accuracy of a claim as low; conversely, a person with a low level of skepticism rate the accuracy of a claim to much higher in the nature of acceptance. Webb and Mohr (1998) indicate that skepticism toward CRM derives mainly from a customer’s distrust or cynicism towards advertising in general. The negative attitudes toward CRM expressed by half of the respondents in their study are attributed towards skepticism of the firm's overall motives. Half of these respondents also perceived of the firm's motives as being "self-serving" in nature. The results suggested that participants with a high level of skepticism would be less likely to respond positively to CRM campaigns than those with a low level of skepticism. Similarly, researchers suggest true when consumers find that some companies actually profit at the expense of the associated cause (Drumwright, 1996; Ellen, Mohr, & Webb, 2000). Some companies are particularly vulnerable to a blanket perception of having poor reputations, when they are perceived as harmful. For example, alcohol and tobacco companies routinely find themselves meeting resistance from some market elements when they choose to undertake socially-oriented campaigns. Consumers often exhibit the widely 21.

(22) held belief that such firms engage in CRM campaigns merely because they wish to mitigate the more harmful effects perceived as coming from their products (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). Ellen, Mohr, and Webb (2000) indicate that it may be entirely unnecessary for companies to be perceived as being purely altruistic in their execution of CRM efforts. Forehand and Grier’s (2003) indicate that efforts such as donating money to cancer research (vs. to an environmental group) for tobacco companies. It will lead to an increased salience of firm-serving benefits by consumers since it is well known that smoking is said to be a direct cause of cancer. Further, a firm sponsors a cause relating to cancer may be seen to be at direct odds with the health consequences. Such a strongly-held perception is likely to undermine a perception of the intended sincerity related to a company’s overall motives. Yoon, Gürhan-Canli, and Schwarz (2006) find that CRM activities serve to improve company evaluations only when sincere motives are attributed or when a company supports a cause that seen as low in benefit salience. CRM activities may possibly become ineffective if consumers have any reason to doubt a company’s motives, such as when a company chooses to support a cause possessing a high-benefit salience as the cancer-related organizations. Szykman (2004) also examine marketing efforts by the tobacco industry, and similarly finds that more positive evaluations are generated whenever such campaign efforts are targeted at reversing decreasing sales of such products. Under this condition, the firm’s motive could be inferred as more society-serving.. 2.6 Concluding Remarks All the theoretical backgrounds related to this thesis have been addressed. This study seeks to provide greater insight into CRM effectiveness. In this chapter, the origin of CRM was first introduced, with related current studies about CRM in practice. Then fit marketing strategy was discussed overall. It also focused on prior research with product type on CRM effectiveness. Besides, the relevant research on the influences of inferred motivation in CRM 22.

(23) was also presented. The literature reviewed in this chapter is the groundwork for developing the hypotheses in Chapter Three.. 23.

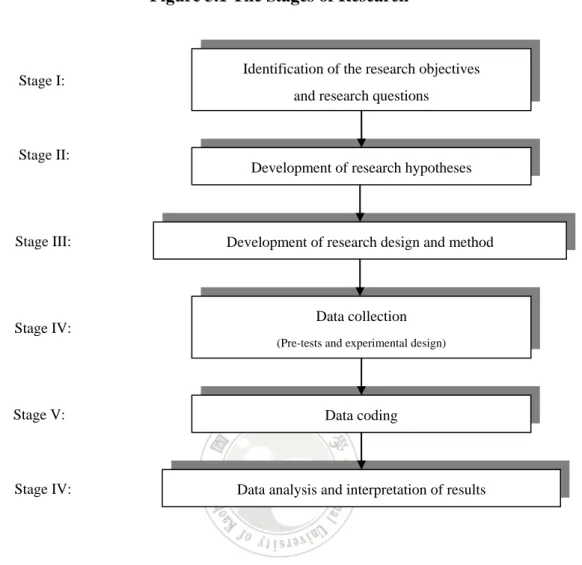

(24) CHAPTER THREE RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHOD. 3.1 Preamble The previous chapter reviewed the current literature and research in the area of CRM. as. well. as. the other relevant important literature. This chapter outlines. hypotheses that were developed from the literature in Chapter 2 and the method for testing the model. It also discusses the research design, treatment of variables, details of the sample data collection and data analysis methods. Critical information regarding the sample of respondents will be reported, and the precise experimental procedures will be also carried out. This includes a comprehensive analysis of the questionnaire design. Throughout all sections, justifications will be furnished with a rationale for the chosen research design and method of data analysis. The chapter concludes the process undertaken in developing and conducting this research is represented diagrammatically at Figure 3.1. This chapter focuses on Stages II–V, and the next chapter (Chapter Four) will focus on Stage VI to report the findings of the study. Then, Chapter Five will summarize conclusions and make suggestions for future research.. 24.

(25) Figure 3.1 The Stages of Research. Stage I:. Identification of the research objectives and research questions. Stage II:. Stage III:. Development of research hypotheses. Development of research design and method. Data collection. Stage IV:. (Pre-tests and experimental design). Stage V:. Data coding. Stage IV:. Data analysis and interpretation of results. 3.2 Hypotheses Prior research has confirmed positive effects of product-cause fit on attitude toward a company and its brand, corporate image, and purchase intention (Han and Ryu 2003). This research is designed to contribute to extend the prior findings by incorporating two variables on CRM effectiveness: product type and product-cause fit. In addition, this research extends the concept of product-cause fit and adopts two distinct views of high fit in CRM with multiple cognitive bases. Thus, two high-fit and one low-fit strategies were examined: consistency fit (i.e., a cause and a product have consistent images or similar values), compensation fit (i.e., a selected cause is used to improve a harmful image of the product through a compensation act) and low fit (i.e., a cause and a product are hardly related to each. 25.

(26) other). In the following, hypotheses will be developed, drawing on appropriate literature for support.. 3.2.1 Influences of Product Type on CRM Effectiveness According to Strahilevitz & Myers' (1998) research, customers most often seek to realize the added value in the purchase of frivolous goods, where they can rationalize their purchases and reduce any cognitive dissonance associated with the exchange. An altruistic act can provide value over and above any tangible consequences by alleviating a negative mood (Strahilevitz, 1999) as guilt. Therefore, CRM is more effective in promoting frivolous, or hedonic products as opposed to utilitarian products (Strahilevitz, 1999; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998). The researchers explain this phenomenon with affect-based complementarity since feelings stimulated by hedonic products complement the feelings generated from contribution to charity. Consistent with this reasoning, it should be easier for people to consume hedonic goods when charity incentive facilitates the justification (Shafir, Simonson, & Tversky, 1993). In particular, recently people are becoming increasingly aware of environmental problems. The nature of the product is not only perceived as frivolous but also with regard to harmful about creating environmental problems through their distribution cycle and package material. Thus, the guilt could be elicited more when consumed these frivolous products with harmful nature. Consequently, consumers are more willing to contribute to a charitable event. These lead to the following hypothesis. H1: CRM with frivolous products will be more effective than CRM with practical ones when the products are perceived as harmful.. 3.2.2 Influences of Product-Cause Fit on CRM Effectiveness The previous research indicates that "fit" between a company and the cause it chooses to represent has been identified as a decisive key in determining the success of CRM. Consumer 26.

(27) attitude towards the high fit between the given company and the chosen cause becomes more favorable in terms of CRM effectiveness, and intent to purchase the sponsored product is higher than in a low fit situation (Gupta & Pirsch, 2006; Lafferty, 2007). Moreover, consumers are willing to pay more for products or services under a high-fit condition (Pracejus & Olsen, 2004). Congruence theory can be used to support an explanation of the effects of fit and then explain why this phenomenon of fit is so important to consumers. It suggests that storage and retrieval of information from memory are influenced by relatedness or similarity. The more congruent the fit, the better the association and retrieval are considered to be. Therefore, even though the products are perceived to be harmful, congruence theory may still be applied in the high-fit condition. This prediction leads to perception of high-fit being more effective than low-fit in CRM. Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed. H2: High fit between the product and the cause will be more effective than low fit between the product and the cause whenever the products are perceived as harmful.. It is believed that CRM activity may not always achieve the intended effects desired (Strahilevitz, 2003; Szykman, 2004; Webb & Mohr, 1988). For example, according to the previous research, tobacco companies donating money to a cancer association leads to an increased salience of firm-serving benefits because of the natural conclusion that smoking causes cancer and the nature of the cause is antithetical to the company’s core’s value. Within a context of CRM, the specific type of cause a company chooses to support will even suggest an increase of salience found in firm-serving benefits rather than in society-serving benefits (Forehand & Grier, 2003; Yoon et al., 2006), and it will cause a negative impact on a company’s consumer evaluation when the company claims itself providing public-serving benefits. Consumers may become more suspicious of a firm’s CRM efforts if the industries in 27.

(28) question are known to engage in harmful activities when they wish instead to undertake socially-oriented campaigns aimed at mitigating the perceived negative effects of their products or services (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002). For instance, a selected cause such as fighting against certain forms of cancer may ameliorate the harmful image through such a compensation act, which in turn is more likely to further undermine consumers’ perceived sincerity of the company’s real motives. Companies may not deem it necessary to be perceived as being purely altruistic in all of their CRM efforts (Ellen et al., 2000). For example, a plastic company may choose to sponsor a local environmental association in order to reduce a marked perception of the harmful effects resulting from production of its wares. However, customers may instead choose to pay more attention to the environmental issues espoused, thus decreasing their frequency of purchase and use of the company’s plastic goods. As a result, this form of CRM may actually hurt a company’s benefits. When corporate benefits are not readily apparent, such benefits will come into conflict with what a consumer already believes about a specific firm or industry. Under these conditions, consumers may instead become more suspicious of a corporation’s underlying motives. Such untoward suspicions may actually trigger an attribution process whereby consumers will attempt to uncover any logical conclusions as to the underlying ulterior motives behind a firm’s decision making. Compensation fit may be viewed as a reminder to consumers of the damage a corporation has inflicted. Therefore, from consumers’ perspective, the motives of compensation fit are not considered to be pure. Based on the above rationale, the following hypothesis is developed. H3: Consistency fit between the product and the cause will be more effective than compensation fit between the product and the cause.. 3.2.3 Relationship between Product Type and Product-Cause Fit on CRM Effectiveness The previous research indicates that hedonic consumption evokes a sense of guilt in 28.

(29) many consumers (Kivetz & Simonson, 2002a, and 2002b; Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998) and charity incentive is a way to provide justifiable options which reduce consumers’ guilt (Hsee, 1996). In particular, when the nature of frivolous product perceived to be harmful, the guilt may not be only from buying the pleasure-oriented consumption but also from the perception of products’ harmful nature. Thus, consumers need more powerful altruistic incentive to justify their consumption. Syzkman (2004) indicates the sponsored cause is chosen to address the deceased use of harmful products, which could be inferred to possess the most society-serving motives and to derive the most CRM effectiveness. Take an example with a plastic company sponsors an environmental association for making up for the damage from their product. Once it is successful, consumers may be starting to pay attention to environment issues and thus decrease the frequency of purchasing this harmful product. Thus, if a selected cause is utilized to improve the company’s perceived negative image of their harmful products through a compensation act, a company’s motivation may be viewed as entirely society-responsible in consumers’ minds, because they can find compelling elements in the structure of the offer to justify the belief that the company is rejecting its basic self-interested nature. Otherwise, consumers may suspect a company’s motivation for sponsorship is sincere or just by raising the issue of companies seeking profit at the expense of the associated cause (Drumwright, 1996; Ellen et al., 2000) in order to gain their attention and preference. Thus, compared with the consistency fit, altruistic incentive seems to more strongly favor the conditions of the compensation fit, which could be viewed as a more effective way to reduce the aforementioned guilt. In particular, through supporting these types of charitable campaigns, when consumers satisfy their altruistic needs, they can feel that they are simultaneously helping the society. Therefore, when a product type characterized as being frivolous, consumers will favor CRM campaigns, especially if the cause chosen is based on some form of compensation. This decision when taken in context allows consumers to justify 29.

(30) their consumption. On the contrary, utilitarian goods tend to be seen as more necessary to consumers and therefore it is easier to construct reasons for them when consumed (Hess, 1996; Shafir et al., 1993). As mentioned earlier, utilitarian consumption is deliberate and in a efficient manner (Babbin et al., 1994). Thus, a utilitarian consumer behavior has been described as task-related and rational (Batra & Ahtola, 1991; Vellucci, 1990). Based on these distinguishing consumer characteristics, the customer is viewed as rational to examine the CRM activities deliberately in the consumption of the utilitarian product. Especially, when a company decides to sponsor a non-profit organization that is the quite opposite of the company’s core values through some kind of compensation act to society, rational consumers may generate a series of questions about why companies are involved in this type of charity activities and how sincere the company chooses a sponsored cause. Furthermore, once this campaign is against the firm’s profit, even result in the negative sales, and a company would not gain any benefit from it, consumers may attempt to uncover the underlying ulterior motive of the firm. Meanwhile, the suspicion could be easily triggered. From the consumers’ perspective, since firms exist to enhance self-interest or to make a profit, consumers may spend considerable energy in an attempt to infer motives related to the profit-oriented goals. While these attributions are inferred to be distrustful in nature, they do typically result in a less favorable evaluation of the firm (Fein et al., 1990). Besides, consumers’ distrust and skepticism toward the company and its CSR will affect the success outcomes of a CRM activity on evaluations (Webb & Mohr, 1988). Some of the inherent risks in this type of compensation act involve a likely reminder to rational consumers of what potential damage a company causes. Thus, there is a chance that has the potential to make CRM initiatives a very risky undertaking. In addition, consumers may be more suspicious of CRM efforts for firms in industries known to be harmful. Consumers might view the company that undertakes socially-oriented campaigns aimed at 30.

(31) mitigating the less-salubrious effects of their products (Hoeffler & Keller, 2002) and improve their negative image as insincere. Hence, the CRM activities possess a constant downside of being discounted, especially under the circumstances of the compensation fit. Based on the discussion above, the relative CRM effectiveness will differ based on the product type under different types of product-cause fit. Thus, the following hypotheses are provided: H4a: Compensation fit between the product and the cause will be more effective when promoting frivolous products. H4b: Consistency fit between the product and the cause will be more effective when promoting practical products.. Based on the outcome of the literature review, this research extends the concept of product-cause fit and adopts two distinct views of high fit in CRM. One is the consistency fit and the other one is the compensation fit. In this research the product type and product-cause fit will be examined separately on CRM effectiveness. Then, a two-way interaction effect is expected to occur since both factors might affect the consumer evaluations simultaneously. Thus, effects of product type will be examined by incorporating with the different types of product-cause fit on CRM effectiveness. The conceptual framework will be all explored in the research. Figure 3.2 summarizes the predicted relationship between product type and the product-cause fit on CRM effectiveness in a model.. 31.

(32) Figure 3.2 The Conceptual Framework and Hypotheses. Product-Cause fit High Fit in Consistency vs. High Fit in Compensation vs. Low Fit H4(a). Product Type Frivolous Product vs. Practical Product. H4a. H2 H3. H4b. CRM Effectiveness H1. 3.3 Method The following section will outline the details of how the research study was conducted including the research design, pilot study, research variables, and administration of the survey procedure. A justification for the method is also provided.. 3.3.1 Research Design and Pretest In order to address above hypotheses and criteria, this study is primarily an investigation of causality. Fundamentally, this research aims to explore what influences the CRM advertising effectiveness. As a result, an experimental design was an appropriate method selected for addressing issues of causality in this context. In the experiment, it was important to select appropriate causes to represent different types of product-cause fit condition manipulated in each version of fictitious CRM advertisement. To eliminate the possibility of confounds, a pretest was conducted to reduce variations in participants’ previous perception and experiences with causes. A pretest allows for a more precise measure of the effect of the treatment (Christensen, 1994). In the following sections, the overview and results of pre-test 32.

(33) will be introduced followed by the experimental design of the research.. 3.3.1.1 Overview of the Pretest In the pretest, the questionnaire (refer to Appendix A) measured both familiarity with and attitudes toward the selected causes separately to ensure that the chosen causes were all equivalent. At the beginning of questionnaire, six given causes involved with the issues of children welfare, environmental protection, care for physically and mentally disabled, human rights protection, care for the elderly, and disease prevention and treatment, which are selected based on most being around in the daily life. The respondents were asked to circle a number on a 7-point bipolar adjective scale ranging from 1 (extremely unfamiliar) to 7 (extremely familiar) that best reflected their degree of familiarity with those six different causes (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005). Similarly, for the following question about favorability, the respondents were asked to circle a number on a 7-point scale that best reflected their feelings toward those six causes. The scale used also ranged from 1 (extremely unfavorable) to 7 (extremely favorable). Finally, participants provided demographic information for classification purposes (i.e., age, gender, major, and allowance per month). At the end, participants were thanked.. 3.3.1.2 Pretest Results Subjects were recruited from one undergraduate class at National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan, and age range was between 18 and 23. Professor allowed the researcher to distribute questionnaires during the first ten minutes of class. Students received no compensation or credit for participation and could freely choose not to participate. The results of pretest indicated that “children welfare”, “environmental protection” and “Care for the elderly” was not significantly different in participants’ familiarity (F (1, 46) <1) or favorability (F (1, 46) <1)., when compared with each other. In terms of other causes 33.

(34) considered in the pretest, consumers had different attitudes toward them which resulted in statistical differences. Therefore, “children welfare”, “environmental protection”, and “care for the elderly” were selected ultimately in the main experiment. Detailed results are presented in Figure 3.3.. Perceptual Degree of the Promoted Cause. Figure 3.3 Pre-test Results of Consumer Perception on the Causes. 6 Familiarity toward the Cause. 5 4. Favorability of the Cause. 3 2 1 0. Cause1. Cause2. Cause3. Cause4. Familiarity toward the Cause. 3.96. 4.33. 3.72. 3.57. 3.8. 4.37. Favorability of the Cause. 4.61. 4.91. 4.61. 4.33. 4.61. 5.24. Cause1 = Children welfare Cause2 = Environmental protection Cause3 = Care for physically and mentally disabled Cause4 = Human rights protection Cause5 = Care for the elderly Cause6 = Disease prevention and treatment. 34. Cause5. Cause6.

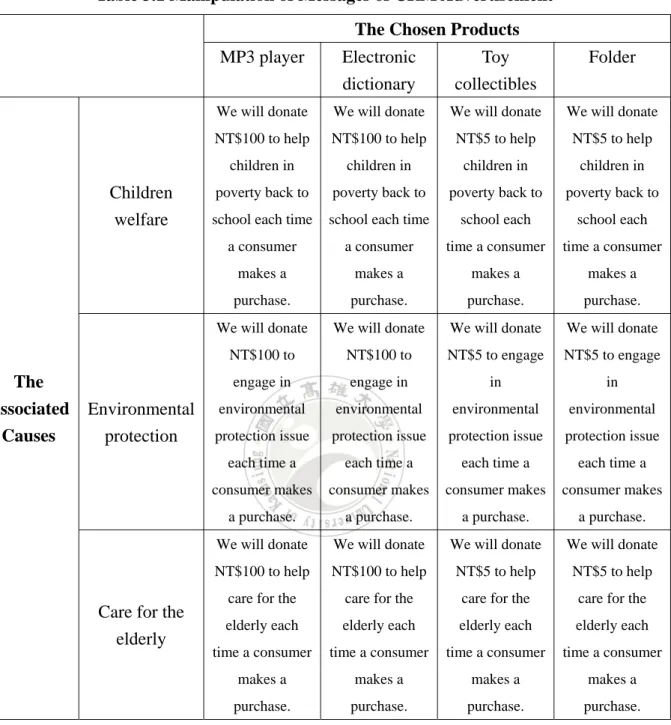

(35) 3.3.2 Experimental Design 3.3.2.1 Overview This research elaborated on the concept of product-cause fit by examining how consumer perceptions of fit nature affected attitudes toward the sponsoring company, and purchase intention in purchase situations with different product types. Thus, an experiment in a 3 (product-cause fit: consistency fit vs. compensation fit vs. low fit) X 2 (product type: practical vs. frivolous) was developed to test the relative CRM effectiveness of advertising messages to promote products that consumers perceive as harmful. In the experiment, it is important to choose product types that consumers could evaluate on attributes that facilitate information processing. Two product types were considered based on previous consumer research (Strahilevitz and Myers, 1998; Strahilevitz, 1999) that should have the potential to be classified frivolous or practical products. To prevent possible product-selection bias, different price levels were considered. With such a consideration in mind, four products were chosen for purpose of the study. Two frivolous products included MP3 players or collectibles toys. An electronic dictionary and a folder were considered as practical products were considered. According to sales prices taken used in actual market conditions, an MP3 player and an electronic dictionary were considered to be among higher-priced products, and collectibles toys and document folders, were seen to be lower-priced products. In addition, those products result in environmental problems through their package material (i.e., plastic), which could be seen as harmful. Based on the results of pretest, children welfare, environmental protection, and care for the elderly were indicated similar perception and attitudes and thus were selected as the alliance causes. Therefore, twelve versions of experimental materials were produced (refer to Appendix B). Prior to the experiment, the questionnaires were randomized. Participants were assigned to one of the twelve experimental conditions.. 35.

(36) 3.3.2.2 Participants Participants consisted of 405 undergraduate students (198males, 196 females, and 11 who failed to identify sex) from ten courses across a variety of disciplines (i.e., natural science, management, engineering, humanities, social science, and law school) in National University of Kaohsiung. 64 participants in pretest did not involve in main experiment. Two participants had to be removed from the analysis because of missing data. In the final valid sample of 403 respondents, age range was between 18 and 24 (M = 20.13, SD = 1.44).. 3.3.2.3 Research Variables 3.3.2.3.1 Independent Variables and Manipulation Two independent variables were of concern in this research: product-cause fit and product type. As noted, four products were chosen for purpose of the study. Two frivolous products included MP3 players or collectibles toys. Two practical products were considered an electronic dictionary and a document folder. In the actual experiment, participants were asked to indicate the perception of product classification for the experiment consistent with definitions derived from previous literature (Strahilevitz & Myers, 1998; Strahilevitz, 1999). The classification scale ranged from 1 (considering it as a completely frivolous product) to 7 (considering it to be a completely practical product). This study adopts two distinct views of the product-cause fit rather than focusing exclusively on one specific aspect of product-cause fit. Throughout this research, product-cause fit was manipulated through a variation of the cause attributes into three different levels: consistency fit (i.e., cause and a product will have consistent images or similar values); compensation fit (i.e., a selected cause is used to improve a possible harmful image through some form of compensation act); and low fit (i.e., a cause and a product are hardly related to each other). Meanwhile, a pretest indicated a set of similar perceptions and. 36.

(37) attitudes towards three different attributes of cause which were “children’s welfare”, “environmental protection” and “care for the elderly”. Since all of the chosen products are related to children, in a consistency fit condition, the involved cause was chosen in regards to “Children welfare”. In the compensation fit condition, since the material found in all of the chosen products is perceived as harmful towards polluting the environment, a cause related to “environmental protection” might mitigate the harmful nature of those products. Thus, it would be more appropriate to choose the involved cause in regards to environmental protection issues. In low fit condition, the involved cause was considered to be “care for the elderly”, because it is nearly unrelated to these four products.. 3.3.2.3.2 Dependent Variables Consumer attitude toward the company and purchase intention were the two dependent variables to evaluate CRM effectiveness in this research. Respondents were asked to circle a number on each of three seven-point adjective pairs that best reflected their attitudes toward the company. Those three, seven-point adjective scales anchored at “positive/negative,” “favorable/unfavorable,” and “likely/unlikely” (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005). Following this, participants indicated their purchase intention in three questions on a 7-point scale (1 = extremely disagree, 7 = extremely agree). Questions included “whether I would purchase a product with CRM if I need,” “I would recommend my friend to purchase a product with CRM,” “I would be willing to pay more for a product with CRM.” The sum of each three items formed the dependent variables separately to represent consumer attitude toward the company and purchase intention.. 3.3.2.3.3 Possible Covariates of Individual Differences on CRM Effectiveness Some covariates were regarding participants’ perception which might influence their choice in CRM. Those questions were presented as follows. 37.

(38) 1. Consumer attitudes toward CRM. Participants indicated their attitudes towards CRM in four questions on a 7-point scale (1 = extremely disagree, 7 = extremely agree). Questions included whether they would purchase a product because of corporate philanthropic activity, whether they have favorable attitudes towards a company acting of altruism, whether they would be willing to pay more for a product with a cause, and whether they would support a company with CRM (Kao, 2006). An index was created by calculating the mean of the four items. 2. Gender Differences. Previous research in CRM has noted gender differences in acceptance of CRM strategies. Women are found to be more likely to support CRM campaigns than men (Ross et al., 1992).The findings suggest that the nurturing personalities of women (Ross et al., 1992). Trimble and Rifon (2006) suggest that the increased level of acceptance expected of women would result in reporting more positive attitudes toward corporations involved in CRM than men. Therefore, gender differences were considered as a potential variable that might confound the experimental results.. 3.3.2.4 Questionnaire and Advertisements The questionnaire used in this experiment consisted of seven parts. The first part evaluated consumer attitudes toward CRM, as it is considered to be a potential variable capable of confounding experimental results. The second part involved questions for checking the manipulation related to product types. Participants were requested to evaluate each listed product on a scale from 1 (considering it as a completely frivolous product) to 7 (considering it as a completely practical product). Response was made by circling one of the seven numbers provided in each question item. Items were arranged prior to the participants exposure to the questionnaire for decreasing the learning effects. The third part of the questionnaire included a variety of color printed advertisements. Products and related sale prices were shown based on actual versions of advertisements 38.

(39) products featured in the marketplace. In an effort to make the advertisements appear realistic, some product features or functions were displayed in the advertisement. (e.g., MP3 with 4 GB, FM stereo) (Refer to Figure 3.4 as examples). Descriptions also emphasized the material used in the manufacture of the product as being Polyvinylchloride (PVC), which was consistent across all experimental conditions. In the bottom of the advertisement space, the exact wording of the CRM message that was based on the different product-cause-fit shows differently (Table 3.1). After viewing of the ad, participants were asked to read a small paragraph related to the definition of consistency fit and compensation fit. Then three product-cause fit options were listed (i.e., consistency fit, compensation fit and low fit). Participants were asked to choose one to represent the relationship of the product and the cause. For the next part, participants were asked to reply as to their purchase intention. After that, questions were related to feelings accompanied with the actual purchase (i.e., pleasure and quilt). Participants were asked to indicate to what extent their purchase was perceived to be boring/fun, mundane/interesting or routine/unusual on three 7-point semantic differential scales. An index was formed by averaging the three items. Participants were then asked to indicate to what extent the product purchase might be perceived as being guilty/guilt free, self-indulgent/not self-indulgent, or regretful/not regretful after their purchase on a 7-point semantic differential scale. An index was created by calculating the mean of these three items. In the fifth part of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to circle a number on each of three seven-point adjective pairs located in the scale that best reflected the respondents’ attitudes toward the company. Those three, seven-point adjective scales were anchored at “positive/negative,” “favorable/unfavorable,” and “likely/unlikely” (Lafferty & Goldsmith, 2005). Following this, the sixth part of the questionnaire, inferred motives that were measured by asking participants to describe reasons for the product-cause partnership determined by using a seven point scale anchored by pure/un-pure, selfish/selfless, 39.

(40) caring/uncaring, society-serving/self-serving, uninvolved/involved, and proactive/reactive pairs. The scale was adopted from Szykman, Bloom, and Blazing (2004), and from Szykman (2004). For the last session, participants were asked to provide the demographic profile (i.e., age, gender, major and allowance per month).. Figure 3.4 Examples of the Copies of Advertisement in the Experiment. Consistency Fit: Frivolous product and child welfare. Compensation Fit: Practical product and environmental protection. Low Fit: Frivolous product and care for the elderly 40.

(41) Table 3.1 Manipulation of Messages of CRM Advertisement The Chosen Products. Children welfare. The Associated Causes. Environmental protection. Care for the elderly. MP3 player. Electronic dictionary. Toy collectibles. Folder. We will donate. We will donate. We will donate. We will donate. NT$100 to help. NT$100 to help. NT$5 to help. NT$5 to help. children in. children in. children in. children in. poverty back to. poverty back to. poverty back to. poverty back to. school each time. school each time. school each. school each. a consumer. a consumer. time a consumer. time a consumer. makes a. makes a. makes a. makes a. purchase.. purchase.. purchase.. purchase.. We will donate. We will donate. We will donate. We will donate. NT$100 to. NT$100 to. NT$5 to engage. NT$5 to engage. engage in. engage in. in. in. environmental. environmental. environmental. environmental. protection issue. protection issue. protection issue. protection issue. each time a. each time a. each time a. each time a. consumer makes. consumer makes. consumer makes. consumer makes. a purchase.. a purchase.. a purchase.. a purchase.. We will donate. We will donate. We will donate. We will donate. NT$100 to help. NT$100 to help. NT$5 to help. NT$5 to help. care for the. care for the. care for the. care for the. elderly each. elderly each. elderly each. elderly each. time a consumer. time a consumer. time a consumer. time a consumer. makes a. makes a. makes a. makes a. purchase.. purchase.. purchase.. purchase.. 3.3.2.5 Administration Procedure Participants were recruited from several undergraduate classes at National University of Kaohsiung. Classes were chosen from various departments with the approval of the class professors. Students were randomly assigned to one of twelve questionnaires representing different experimental conditions. There was no compensation or credit for participation.. 41.

數據

+7

相關文件

相關研究成效,開發能源屋作為節能之教具並商品化推廣,藉以達到產品的有用

本作品希望透過 數位科技 與 藝術創作 產生的激盪,讓人、環境、科技 之間形成更和諧、優質的生活形態。.. 因此將利用數位科技的 互動性

歐盟對於紡織品、鋼鐵、化學品等產品,有增加運用 反傾銷及反補貼法規,以保護其國內產業之趨勢。例 如聚酯棉(synthetic polyester fibers)案的反傾銷措

稅則號別變更標準:指生產貨品所使用的非原產材料 在締約一方或雙方領域內加工,因而使貨品之稅則號 別發生;換言之

八、水產加 工食品 之原 料、半 成品、.

翻譯源自 © copyright Games Workshop Ltd © copyright Games Workshop Ltd © copyright Games Workshop Ltd 之系列產品 © copyright Games Workshop Ltd 之系列產品

斯蘭HALAL清真食(用)品證」(以下簡稱「清真食(用)品證」),應填寫本寺專用申請書並繳付申請 捐款(手續費);申請續約 申請續約

翻譯源自 © copyright Games Workshop Ltd © copyright Games Workshop Ltd © copyright Games Workshop Ltd 之系列產品 © copyright Games Workshop Ltd 之系列產品