Modeling Corporate Citizenship,

Organizational Trust, and Work

Engagement Based on Attachment Theory

Chieh-Peng Lin

ABSTRACT. This study proposes a research model based on attachment theory, which examines the role of corporate citizenship in the formation of organizational trust and work engagement. In the model, work engagement is directly influenced by four dimensions of perceived corporate citizenship, including economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary citizenship, while work engagement is also indirectly affected by perceived cor-porate citizenship through the mediation of organiza-tional trust. Empirical testing using a survey of personnel from 12 large firms confirms most of our hypothesized effects. Finally, theoretical and managerial implications of our findings are discussed.

KEY WORDS: corporate citizenship, discretionary cit-izenship, ethical citcit-izenship, organizational trust, work engagement

Introduction

A recent growing interest in positive psychology emphasizing human strengths, optimal functioning, and well-being has led to the emergence of the concept of work engagement (Chughtai and Buckley,2008). Work engagement is defined as a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (Schaufeli et al., 2006). First, vigor is featured with high levels of energy and mental resilience when individuals work (Bakker and Demerouti,2008). Second, dedication refers to a strong identification with their work and encompasses feelings of enthusiasm, inspiration, pride, and chal-lenge (Chughtai and Buckley,2008). Third, absorp-tion encompasses being fully concentrated and happily engrossed in individuals’ work, in which time passes quickly and individuals have difficulties with detach-ing themselves from work (Bakker and Demerouti,

2008). Based on the foregoing definition of work engagement, it is important to note that work engagement is viewed as managing discretionary effort in which employees act in a way that furthers their organization’s interests.

Work engagement involves the expression of the self through work and other employee-role activities. Work engagement should be carefully cultivated since that disengagement brings serious problems such as weak commitment (Fay and Luhrmann, 2004), dis-trust (Chughtai and Buckley, 2008), high burnout (Gonza´lez-Roma et al.,2006), and low performance (Salanova et al.,2005). Thus, identifying those situa-tions that foster work engagement of employees is vital for the sustainability and growth of business organizations. Particularly, engagement can be seen as harnessing organization members’ selves to their work roles (Barkhuizen and Rothmann, 2006). The more employees draw upon their selves to perform their roles, the better are their performances (Barkhuizen and Rothmann,2006). In contrast, employees’ work disengagement that causes the uncoupling of their selves from their work roles can generate unnecessary organizational transaction costs from excessive mon-itoring and enforcement (Williamson,1985). For that reason, trust becomes critical to strengthen work engagement and, consequently, lower such transac-tion costs (e.g., Dyer and Chu, 2003; Fukuyama, 1995). Previous evidence indicates that employees are more likely to engage in their work when they have developed a high level of organizational trust (e.g., Chughtai and Buckley, 2008). This study defines organizational trust as employees’ willingness at being vulnerable to the actions of their organization, whose behavior and actions they cannot control (e.g., Tan and Lim,2009).

A potential issue for employees in their job career is to be enthusiastic about and fully involved with their work as shown via the social practices of their work organization in corporate citizenship (Bakker and Demerouti, 2008). Learning how work engagement is driven by the determinants related to today’s social practices is essential due to dramatic social changes in business communities.

Business communities increasingly prefer corpo-rate citizenship to be a set of meaningful social practices that are helpful for not only improving their reputation in public, but also for winning the work engagement and trust of their employees. This is understandable, because work engagement and organizational trust can be achieved through the meaningfulness of work (Morrison et al., 2007). A majority of research has explored numerous determinants of work engagement from three major aspects: individuals (e.g., personality), their job (job control), or inter-organizational characteristics (e.g., social support). However, there still lacks an understanding about how work engagement and trust are driven by corporate citizenship, which are out of the scope of the above three aspects. Against such a backdrop, this study proposes a refined operationalization of the corporate citizenship con-structs and empirically links the concon-structs to work engagement and trust.

Corporate citizenship – also known as corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate responsibility and responsible business – is a form of corporate self-regulation integrated into a business model (Wood, 1991). Corporate citizenship is developing rapidly across a variety of popular initiatives, such as the financing of employees’ education, promoting ethics training programs, adopting environment-friendly policies, and sponsoring community events (Maignan and Ferrell,2000). Examples of benefits from corporate citizenship for a firm may result in the ability to charge a premium price for its product, obtaining a good busi-ness image or to attract investment.

Most previous research tends to emphasize the influence of corporate citizenship on instrumental or utilitarian factors such as business performance or a consumer’s purchase (e.g., Becker-Olsen et al., 2006; Waddock and Graves, 1997). For instance, Siegel and Vitaliano (2007) emphasize how the activity of corporate citizenship should be integrated into a firm’s differentiation strategies to impact sales

and profits. It is even asserted that firms compete for socially responsible customers by explicitly linking their social contribution to product sales (Baron, 2001).

Despite many studies linking corporate citizenship to instrumental factors (e.g., performance, profit, and purchase) (e.g., Maxfield, 2008; Shen and Chang, 2009), our current knowledge about how corporate citizenship impacts affective or relational factors, particularly organizational trust and work engagement, is somewhat insufficient. Indeed, work engagement that represents employees’ psychologi-cal attachment to their work assigned by their organization has been often ignored in corporate citizenship literature. Thus, the purpose of this study research is to examine the relationship between corporate citizenship, organizational trust, and work engagement so as to complement previous research in the area of CSR. A potential explanation for the relationship can be provided based on attachment theory in which employees have intrinsic and affective needs for a secure relationship with the organization for which they work.

Previous research indicates that attachment theory can be strongly used to explain various aspects of work behavior based on adult attachment types (e.g., secure, anxious-preoccupied, and dismissive avoid-ant) (Hardy and Barkham, 1994). Based on attach-ment theory, corporate citizenship may be expected to contribute positively to the affection, attribution, retention, and motivation of employees, because the employees often show strong attachment manifes-tations toward their organization regarding corporate citizenship. Drawing on attachment theory, this study postulates that the attachment manifestations such as employees’ engagement in organizational work and their organizational trust are adaptive responses to separation from a primary attachment figure – someone who provides, for example, eco-nomic and legal support (e.g., care and protection). Overall, this study’s key research question is: ‘‘which dimensions of perceived corporate citizenship have an influence on work engagement and organiza-tional trust?’’ Understanding this question helps management plan corporate citizenship activities efficiently so as to facilitate employees’ organiza-tional trust and work engagement.

This study differs from previous research in two important ways. First, previous studies linking

per-ceived corporate citizenship to trust or work engagement do not examine the various dimensions of such citizenship (i.e., economic, legal, ethical, and discretionary citizenship) (e.g., Brammer et al., 2007). For that reason, this study evaluates corporate citizenship based on its four dimensions, which is relevant to how organizational members obtain a further understanding about the influence of these four dimensions on work engagement according to attachment theory. This is important, because some researchers studying corporate citizenship have failed to take its multi-dimensional nature into account (De los Salmones et al.,2005). Second, this study is a pioneer in examining the mediating role of organi-zational trust (i.e., a partial mediator) in the rela-tionship between different dimensions of corporate citizenship and work engagement. That is, corporate citizenship is expected to have direct effects on work engagement and indirect effects on work engage-ment via the mediation of organizational trust. Although organizational trust as a mediating role across different organizational issues has been somewhat discussed in previous research, none of the previous research has considered organizational trust as a mediator in the relationship between cor-porate citizenship and work engagement. Collec-tively, by evaluating the main effect of corporate citizenship on work engagement and the mediating effects of organizational trust in the work engage-ment formation, a clear picture of how corporate citizenship actually influences work engagement can be significantly developed.

Theory and development of hypotheses Corporate citizenship is a high-profile notion that has strategic significance to business firms. It also represents a firm’s activities and status related to the firm’s perceived societal and stakeholder obligations (Luo and Bhattacharya, 2006). Some researchers have studied the degree to which corporate citi-zenship is applied in firms (Joyner and Payne,2002), while others have tried to measure the relation between social performance (i.e., corporate citizen-ship) and employer attractiveness (Backhaus et al., 2002). However, none of previous studies have tried to clarify how different dimensions of corporate citizenship influence employees’ work engagement

and organizational trust, which is examined in this study based on attachment theory. Attachment the-ory is recognized as a lifespan developmental thethe-ory relevant for understanding how certain affectional experiences impact emotional and physical well-being not only during childhood, but also throughout adulthood during their working profession as well (Sable,2008). The organization may often serve as the attachment figure. In order for the relationship between employees and their organization to evoke attachment dynamics, the relationship must involve some types of affectional bond (e.g., corporate citi-zenship) (e.g., Keller and Cacioppe,2001).

Attachment theory is based on the premise that human beings, like many other animals, have a natural inclination to make and maintain lasting affectional bonds – or attachments – to familiar, irreplaceable organizations (Sable, 2008), and once established the quality, security, and stability of the ties are likely to lead to individuals’ belief and work behavior in the organization (e.g., Nelson and Quick, 1991) such as work engagement and orga-nizational trust. In other words, given important ties with their organization, employees’ work engage-ment and organizational trust are likely influenced by various dimensions of corporate citizenship shown by the organization, as is introduced in detail as follows.

Corporate citizenship consists of four dimensions refined from previous literature in terms of employees as stakeholders: (1) economic citizenship, referring to the firm’s obligation to bring utilitarian benefits to various stakeholders (e.g., Zahra and LaTour,1987); (2) legal citizenship, referring to the firm’s obligation to fulfill its business mission within the framework of legal requirements; (3) ethical citizenship, referring to the firm’s obligation to abide by moral rules defining proper behavior in society; and (4) discretionary citizenship, referring to the firm’s obligation to engage in activities that are not mandated, not required by law, and not expected of business in an ethical sense (Maignan and Ferrell, 2000). Note that although economic citizenship may contain the firm’s economic obligations to various stakeholders (e.g., consumers, investors, employees, etc.), this study focuses on the obligations directly relevant to employees (e.g., training, education, quality working environment, etc.) so that the genuine influence of economic citizenship on

organizational trust and work engagement can be properly validated herein.

Examining different dimensions of corporate cit-izenship is like opening up the black box of cor-porate citizenship, because such citizenship does mean something, but not always the same thing, to everybody (Turker, 2009). For example, whereas economic citizenship regarding welfare or training has a monetary or utilitarian influence on employees, ethical citizenship regarding morals yields a psy-chological or purely social impact on employees. Hence, it would be inappropriate for management to only focus on ethical codes (while ignoring financial incentives) if it is economic citizenship that goes wrong.

The necessary and foremost social responsibility of a business is economic in nature, because the business organization is the basic economic unit in our society (Carroll, 1979) that takes care of its employees or other stakeholders (Maxfield, 2008; Turker, 2009). As such, it has a responsibility to provide secure job opportunities, training, and career development while producing goods (or services) and selling them at a profit (Weyzig, 2009). Based on attachment theory, with an economically secure base in rela-tionships, employees feel freer to explore new work experiences and job activities while being assured of a comfortable and reassuring refuge to return to should this be needed (Sable,2008), implying the potential relationship between perceived economic citizenship and work engagement. Attachment-based research means that a characteristic of economically secure attachment is the capacity to rely trustingly on the organization when the occasion demands it (e.g., Bowlby,1973), suggesting the influence of perceived economic citizenship on organizational trust.

The basic work engagement and organizational trust of employees can be initially driven when their firm is able to demonstrate economic citizenship by providing their basic work and life quality. First, employees will be more absorbed in their work after they perceive their organization is performing social responsibility economically for the good of the employees. Second, employees’ trust toward their organization is likely boosted when their satisfaction about economic offers in the job context (e.g., payoff or promotion) is obtained (e.g., Williams, 2005). Collectively, the hypotheses about the

influence of perceived economic citizenship is de-rived as follows.

H1: Perceived economic citizenship is positively related to work engagement.

H2: Perceived economic citizenship is positively related to organizational trust.

Just as society has sanctioned the economic system by allowing business to assume the productive role as a partial fulfillment of the ‘‘social contract,’’ it has also laid down the ground rules, the regulations, and law under which business is anticipated to operate (Carroll,1979). In attachment theory, secure attach-ment and adaptive functioning (in which legal citi-zenship is presented) may be promoted by an organization which is appropriately responsive to its employees’ attachment behavior, swaying both their positive and negative working emotions in their organizations (Sable, 2008). For example, in com-parison to insecurely attached individuals (caused by illegal corporate citizenship), securely attached employees (i.e., those who do not have to break the law when performing their job) show better job sat-isfaction, better work styles (e.g., who they work with – alone, with others, or the number of people with whom they interact) that do not jeopardize their health or relationships with others, and fewer worries about work performance and colleagues (Hardy and Barkham,1994), assuming the potential influence of perceived legal citizenship on work engagement.

Society’s members expect a business to fulfill its mission within the framework of legal requirements (Carroll, 1979), and thus employees’ work engage-ment and organizational trust can be positively driven under circumstances of fulfilled legal citi-zenship by their organization (e.g., Becker, 1998). On the contrary, if the organization engages in illegal behavior and breaks the law, then it would obviously strengthen employees’ feelings of suspi-cion, anxiety, and insecurity, resulting in disen-gagement from work (Chughtai and Buckley,2007) and low organizational trust. Thus, the hypotheses are derived as follows.

H3: Perceived legal citizenship is positively related to work engagement.

H4: Perceived legal citizenship is positively related to organizational trust.

Ethical corporate responsibilities of a firm represent behaviors and activities that are not necessarily codified into law, but nevertheless are anticipated from a business by society’s members and a firm’s employees (Carroll, 1979). Employees’ perceptions about their firm’s ethics and social responsiveness play a significant role in motivating employees to engage with their work and foster their organiza-tional trust. When employees perceive that their firm conducts business in accordance with morality and ethics beyond the basic legal requirements, they are positively stimulated by the firm and its assigned work, leading to a positive relationship between ethical citizenship and work engagement.

Attachment theory’s basic proposition is that attachment needs (an emotional bond based on care-seeking and care-giving behavior) are primary, and when they are sufficiently met, then an explora-tion of the environment occurs (Hardy and Barkham, 1994). Thus, when employees experience their organization (i.e., caregiver) as being responsive to ethical citizenship, their work engagement is likely stimulated based on the positive attachment with the organization. Accordingly, ethical responsibility taken by firms refers to them being honest in their relationship with their own employees (De los Salmones et al., 2005), and thus the employees are likely to reciprocate with their strong trust toward the organization. Hence, the hypotheses about the influence of perceived ethical citizenship are provided as follows.

H5: Perceived ethical citizenship is positively related to work engagement.

H6: Perceived ethical citizenship is positively related to organizational trust.

Discretionary corporate responsibilities are those about which society has no clear-cut message for business, and such discretionary corporate responsi-bilities are left to individual judgment and choice (Carroll,1979). When employees observe that their firm takes such responsibilities and reveals good vol-untary citizenship in a society, their psychological confidence about the organization is likely boosted (e.g., Maerki,2008), leading to a positive relationship between perceived discretionary citizenship and organizational trust. Examples of discretionary actions by firms can be making philanthropic donations,

establishing partnerships with non-profit organiza-tions, preserving environmental resources, or caring for social welfare. These actions when presented by an organization help increase its credits and reliability that uplift its employees’ organizational trust.

Research evidence shows that employees are highly concerned about the values of the firm and inter alia its socially responsible behavior beyond the requirement by law (Brammer and Millington, 2003). A survey finds that more than half of the UK employees care very much about the social and environmental responsibilities of their work organi-zation (Dawkins, 2004). Indeed, attachment theory helps explain the self-fulfilling nature of employees’ expectations on leadership or their organization (Keller and Cacioppe,2001), and so employees’ work engagement and organizational trust likely increase with the realization of their expected discretionary citizenship. More specifically, given that work engagement is seen as managing discretionary effort in which employees will act in a way that furthers their organization’s interests, when the discretionary citi-zenship presented by the organization is perceived to be good, employees naturally obtain full engagement with their work. In summary, the hypotheses are provided as follows.

H7: Perceived discretionary citizenship is positively related to work engagement.

H8: Perceived discretionary citizenship is positively related to organizational trust.

Organizational trust (i.e., trust in an organization) involves employees’ willingness to be vulnerable to their organization’s actions or policies (Schoorman et al., 2007). This willingness can be rendered only when an organization clearly communicates its actions or policies with its employees through formal and informal channels (Tan and Lim,2009). There is no single factor which so thoroughly affects indi-viduals’ behavior as does trust, because trust between firms and their employees is a highly critical ingre-dient in the long-term stability of the firms and the well-being of their employees (Tan and Tan, 2000). Whereas organizational trust represents individuals’ confidence and expectations about the actions of their organizations, work engagement reflects their subsequent involvement with and enthusiasm about their work assigned by the organization, implying

the potential influence of the former on the latter. In other words, organizational trust positively affects work engagement, which includes dedication, vigor, and absorption, based on three reasons. First, employees dedicate themselves to the organization as long as they enjoy trusting relationships with the organization (e.g., Gill, 2008). Second, organiza-tional trust represents important core values that help to keep employees creative and energetic (e.g., Simmons, 1990). Third, organizational trust is the means by which employees are absorbed and engaged in the continual improvement of everything the organization does (Townsend and Gebhardt, 2008).

It is crucial to note that while corporate citizen-ship is found to be related to organizational trust (Lamberti and Lettieri,2009), organizational trust is confirmed to be a significant predictor of work engagement (Chughtai and Buckley, 2008), sug-gesting the mediating role of organizational trust between corporate citizenship and work engage-ment. When an organization’s corporate citizenship is perceived to be low by its employees, distrust is likely maximized in the organization and the work engagement of employees is adversely affected.

Previous research indicates that organizational trust affects global job variables, such as organiza-tional commitment, work engagement, and turn-over intention, which impact the entire organization (Chughtai and Buckley,2007; Tan and Tan,2000). When employees trust that competent decisions can be made by their organization, it increases their sense of a future with the organization (Spreitzer and Mishra,2002) and thus enhances their willingness to engage with their work (Chughtai and Buckley, 2007). Organizational trust postulates that the organization will deliver on its promises. Therefore, if employees realize that their organization has failed to fulfill its promised inducements (or policies), then it results in a loss of organizational trust (Robinson, 1996), perhaps leading to work disengagement. Consequently, the hypothesis regarding the influ-ence of organizational trust on work engagement can be stated as follows.

H9: Organizational trust is positively related to work engagement in which organizational trust is a partial mediator between work engagement and its antecedents.

Methods

Subjects and procedures

The research hypotheses described above were empirically tested using a survey of personnel from 20 large firms of an industrial zone in northern Taiwan, including both traditional and high-tech firms. Surveying our sample subjects across various firms is very appropriate and useful for empirically testing our hypotheses related to corporate citizen-ship, because different types of firms have a varying focus on the many dimensions of corporate citi-zenship. Of the 600 questionnaires distributed to the subjects, 428 usable questionnaires were collected for a response rate of 71.33%.

Measures

The constructs in this study are measured using 5-point Likert scales drawn and modified from previous literature (De los Salmones et al., 2005; Maignan and Ferrell,2000; Mayer and Davis, 1999; Schaufeli et al., 2006; Zahra and LaTour, 1987). Three steps are employed in choosing measurement items. First, the items from the existing literature are translated into Chinese from English, and then the items in Chinese were substantially modified by a focus group of four people familiar with CSR, including three graduate students and one professor. Second, following the questionnaire design, we next conducted two pilot tests (prior to the actual survey) to assess the quality of our measures and improve item readability and clarify further if needed. Note that the subjects in the pilot tests are working pro-fessionals from the manufacturing and servicing industries and are also excluded from the subsequent actual survey. The credence of the subjects is good, because they volunteered to help fill out with our questionnaire. Finally, tips of back-translation sug-gested by Reynolds et al. (1993) were used in simultaneously examining an English version ques-tionnaire as well as a Chinese one. A high degree of correspondence between the two questionnaires (evaluated and confirmed via a qualitative assessment by our focus group) assures this research that the translation process did not substantially introduce

artificial translation biases in the Chinese version of our questionnaire.

Work engagement containing vigor, dedication, and absorption is measured perceptually using six items drawn from Schaufeli et al. (2006). Among the six items, vigor is measured with the first two items, and dedication is measured with the third and fourth items. Absorption is measured with the last two items. These items are found to be highly correlated to one another and thus are used together for mea-suring work engagement (Chughtai and Buckley, 2008). Organizational trust is measured using three items directly drawn from Mayer and Davis (1999). Perceived economic citizenship from the aspect of employees’ benefits is measured using four items modified from Zahra and LaTour (1987). Note these items that focus on economic citizenship related to employees herein are quite different from those in previous studies focusing on customers’ benefits, market profits, etc. Perceived legal citizenship from the aspect of law is measured using four items modified from Maignan and Ferrell (2000). Per-ceived ethical citizenship from the aspect of ethical business practices is measured using four items modified from Maignan and Ferrell (2000). Finally, discretionary citizenship from the aspect of social welfare and philanthropy is measured using two items re-worded from Maignan and Ferrell (2000) and another two items re-worded from De los Salmones et al. (2005). These items focus on discretionary is-sues related to stakeholders outside the firm rather than its employees. Appendix lists all the measure-ment items.

Data analysis

The survey data were analyzed using a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) approach proposed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). While the first step performs confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on all data collected to assess scale reliability and validity, the second step examines path effects and significances in the hypothesized structural model for purposes of testing the hypotheses. Empirical test results from each stage of analysis are presented next.

Measurement model testing

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed on all items corresponding to the six constructs measured in Likert-type scales. The goodness-of-fit of the CFA model was assessed using a variety of fit met-rics, as shown in TableI. The root mean square residual (RMR) is smaller than 0.05 and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) is smaller than 0.08. Whereas the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) is slightly smaller than 0.90, the additional indices including the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normed fit index (NNFI), and the normed fit index (NFI) all exceed 0.90. These figures suggest that the hypothesized CFA model in this study fits well within the empirical data.

Three criteria recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981) were examined to confirm the con-vergent validity of the empirical data in this study. First, as evident from the t statistics listed in TableI, all factor loadings were statistically significant at p < 0.001, which is the first requirement to assure convergent validity of the construct (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988). Second, the average variance extracted (AVE) for all constructs exceeded or equaled 0.50, indicating that the overall hypothe-sized items capture sufficient variance in the underlying construct than that attributable to mea-surement error (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Third, the reliabilities for each construct exceeded 0.70, satisfying the general requirement of reliability for research instruments. Thus, the empirical data col-lected by this study meet all three criteria required to support convergent validity.

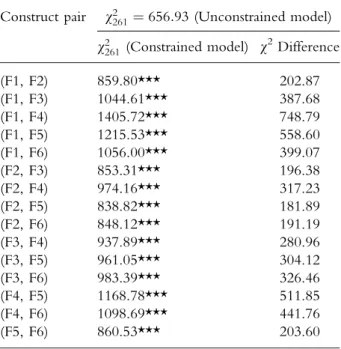

Discriminate validity was assessed by v2difference tests between an unconstrained model, where all constructs in our CFA model were allowed to co-vary freely with constrained models and where covariance between each pair of constructs is fixed at one. The advantage of using this technique is the simultaneous pair-wise comparisons for the structs based on the Bonferroni method. By con-trolling for the experiment-wise error rate by setting the overall significance level to 0.01, the Bonferroni method indicated that the critical value of the v2 difference should be 11.58. Our v2 difference sta-tistics for all pairs of constructs in this study exceeded this critical value of 11.58 (see Table II), thereby

supporting discriminate validity for our data sample. Collectively, the empirical test results in this study indicate that research instruments used for measuring the constructs of interest in this study are statistically adequate.

Structural model testing

The second step transforms the CFA model to a structural model that reflects the hypothesized asso-ciations described in our research model for purposes of testing the hypotheses. TableIII presents the test results of this analysis. Besides, TableIV presents direct effects of our four antecedents on work engagement and their indirect effects via the medi-ation of organizmedi-ational trust.

Results

Seven out of our nine model paths were significant at the p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 significance levels, and these empirical test results show that only hypotheses H4 and H5 are unsupported, while the other hypotheses are fully supported in this study. Partic-ularly, the direct and indirect effects presented in Table IVsupport that organizational trust is a partial mediator between work engagement and its ante-cedents. The insignificant relationship between perceived legal citizenship and organizational trust (H4) indicates that the influence of other perceived citizenship (e.g., economic and ethical citizenship) potentially surpasses that of perceived legal citizen-ship on organizational trust. It may occur, because, for example, the economic issues (e.g., job career TABLE I

Standardized loadings and reliabilities

Construct Indicators Standardized loading AVE Cronbach’s a

Work engagement WE1 0.83 (t = 20.63) 0.68 0.93

WE2 0.85 (t = 21.49) WE3 0.85 (t = 21.74) WE4 0.84 (t = 21.07) WE5 0.76 (t = 18.17) WE6 0.80 (t = 19.70) Organizational trust TR1 0.80 (t = 18.65) 0.62 0.82 TR2 0.78 (t = 17.93) TR3 0.78 (t = 18.13)

Perceived economics citizenship EC1 0.73 (t = 16.87) 0.61 0.86

EC2 0.78 (t = 18.39) EC3 0.80 (t = 19.24) EC4 0.82 (t = 19.87)

Perceived legal citizenship LE1 0.85 (t = 21.29) 0.73 0.90

LE2 0.86 (t = 21.81) LE3 0.83 (t = 20.66) LE4 0.87 (t = 22.15)

Perceived ethical citizenship ET1 0.82 (t = 19.98) 0.67 0.89

ET2 0.83 (t = 20.36) ET3 0.81 (t = 19.90) ET4 0.82 (t = 20.18)

Perceived discretionary citizenship DI1 0.72 (t = 16.67) 0.62 0.87 DI2 0.76 (t = 17.77)

DI3 0.81 (t = 19.60) DI4 0.86 (t = 21.46)

Goodness-of-fit indices (N = 428): v2602 = 656.93 (p value < 0.001); NNFI = 0.94; NFI = 0.92; CFI = 0.95;

development) that are always a main concern by individuals are likely to make other factors less sig-nificant in terms of their organizational trust. The

insignificant relationship between perceived ethical citizenship and work engagement (H5) implies that ethical matters have little to do with individuals’ pleasure and immersion about their job. Neverthe-less, the unexpected results for the unsupported hypotheses may warrant further study so that the insights behind the insignificant models paths can be interpreted accurately.

Discussion

Implications for research

This research confirms some positive influences of four dimensions of corporate citizenship on organi-zational trust and work engagement, further com-plementing previous research that empirically considers corporate citizenship as purely a construct (e.g., Brammer et al.,2007). Additionally, this study is an important bridge between corporate citizenship and work engagement, because many previous studies mostly link corporate citizenship to certain positive outcomes related to customers’ or financial profits (e.g., Becker-Olsen et al., 2006).

A unique finding that has not been found in any previous research is that perceived corporate citi-zenship affects work engagement directly and indi-rectly via the mediation of organizational trust. The finding of this study is an extraordinary contribution by showing a new direction for future research to explore more perceptional mediators (in addition to organizational trust) better understand their various impacts on the linkages between corporate citizen-ship and work engagement. Particularly, future research may include some potential mediators that have not been tested before, such as psychological contract, social identity, job satisfaction, etc. Previ-ous research based on attachment theory never examined how a firm’s corporate citizenship leads to its employees’ organizational trust and work engagement. Although it is well known that ‘‘action speaks louder than words,’’ only a small percentage of business organizations truly care about the actions they have taken in corporate citizenship that affects their employees’ trust and work engagement (Knapp, 2007; Mathews, 2007).

The empirical findings of this study (see TableIV) suggest that organizational trust is a partial mediator TABLE II

v2

difference tests for examining discriminate validity Construct pair v2 261¼ 656:93 (Unconstrained model) v2 261 (Constrained model) v 2 Difference (F1, F2) 859.80*** 202.87 (F1, F3) 1044.61*** 387.68 (F1, F4) 1405.72*** 748.79 (F1, F5) 1215.53*** 558.60 (F1, F6) 1056.00*** 399.07 (F2, F3) 853.31*** 196.38 (F2, F4) 974.16*** 317.23 (F2, F5) 838.82*** 181.89 (F2, F6) 848.12*** 191.19 (F3, F4) 937.89*** 280.96 (F3, F5) 961.05*** 304.12 (F3, F6) 983.39*** 326.46 (F4, F5) 1168.78*** 511.85 (F4, F6) 1098.69*** 441.76 (F5, F6) 860.53*** 203.60

F1 Work engagement, F2 organizational trust, F3 per-ceived economic citizenship, F4 perper-ceived legal citizen-ship, F5 perceived ethical citizencitizen-ship, F6 perceived discretionary citizenship.

***Significant at the 0.001 overall significance level by using the Bonferroni method.

TABLE III

Path coefficients and t value

Hypothesis Standardized coefficient t Value

H1: F3 fi F1 0.20* 2.53 H2: F3 fi F2 0.36** 4.32 H3: F4 fi F1 0.14* 2.14 H4: F4 fi F2 -0.13 -1.79 H5: F5 fi F1 -0.06 -0.75 H6: F5 fi F2 0.30** 3.47 H7: F6 fi F1 0.27** 3.52 H8: F6 fi F2 0.29** 3.50 H9: F2 fi F1 0.35** 4.95 *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Note: Both p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 are the most popular and acceptable significance levels (Nelson,1999).

that affects work engagement but not vice versa. This is theoretically justifiable because employees’ work engagement is unlikely fostered if they work for their organization with distrust. Organizational trust acting as a determinant of work engagement rather than an outcome has been partially supported in previous literature (Chughtai and Buckley,2009).

Implications for practice

The test results show that work engagement can be directly improved by strengthening various perceived corporate citizenship such as economic, legal, and discretionary citizenship, suggesting ‘‘do as you would be done by.’’ Note that work engagement cannot be arbitrarily obtained by an immediate decree of man-agement, but rather it can be achieved after employees observe in depth their firm’s actions in different social perspectives (e.g., legal and ethical ones).

The view of multiple influencers (i.e., various dimensions of corporate citizenship) is quite differ-ent from that of traditional literature purely focusing on workplace conditions or rewards in affecting work engagement without recognizing the necessity of firms’ social responsibilities. Indeed, the given definitions of the various dimensions of corporate citizenship are closely interrelated with the different concepts and values of stakeholders (e.g., employees) (Turker, 2009). By understanding the various dimensions in depth, this study can help manage-ment tailor a variety of organizational policies or programs to individuals’ needs to consequently strengthen their organizational trust and work engagement. For instance, if different dimensions of

corporate citizenship are not examined separately, then management will have no idea which areas of corporate citizenship cause organizational distrust or work disengagement, let alone know where they should put their resources. In fact, organizations that lack social responsibilities are unlikely to boost their employees’ work engagement in the long run (Cartwright and Cooper, 2009; Grayson and Hodges, 2004). Management should strive for the goal of accomplishing all-around corporate citizen-ship and also appropriately disseminate the firm’s vision on corporate citizenship through internal communication channels in order to ultimately enhance their work engagement. Taking legal citi-zenship for example, management may want to avoid any opportunistic behavior that may hazard business legitimacy in order that corporate legal citizenship can be well perceived by the employees. Regarding the significant influence of corporate citizenship on work engagement via the mediation of organizational trust, this study empirically indi-cates that organizational trust can be properly used as an important check-point for detecting work engagement in corporate citizenship. Management should know that employees are very sensitive to any confusion about corporate social activities in which their organizational trust is weakened. For example, once management has detected employees’ low trust in the organization, management should further fortify corporate citizenship by transcribing business activities and verifying such activities as organizational core values to the employees in order to win their trust.

The positive influence of perceived economic citizenship on both organizational trust and work TABLE IV

Direct and indirect effects of the four antecedents on work engagement Path Indirect effects through

organizational trust

Direct effects Total effects

F3 fi F1 0.13 (39%) 0.20 (61%) 0.33

F4 fi F1 0.00 (0%) 0.14 (100%) 0.14

F5 fi F1 0.11 (100%) 0.00 (0%) 0.11

F6 fi F1 0.10 (27%) 0.27 (73%) 0.37

F1 Work engagement, F2 organizational trust, F3 perceived economic citizenship, F4 = perceived legal citizenship, F5 perceived ethical citizenship, F6 perceived discretionary citizenship.

engagement suggests the fundamental substantiality of individuals’ economic needs as the first priority across all business issues. Despite the job opportunities provided by the organization, management should also bear in mind the interest of individuals’ career development and advancement when facilitating their organizational trust and work engagement.

The positive influence of perceived discretionary citizenship on both organizational trust and work engagement exhibits that discretionary citizenship helps employees’ morale and drives them to offer increased organizational trust and work engagement. This empirical finding is very unique and important for understanding work engagement which is seldom examined with an antecedent related to external dis-cretionary behavior (i.e., disdis-cretionary citizenship).

Limitations of the study

This study contains three limitations related to the measurements and interpretations of the results. The first limitation is the possibility of common method bias, given that the predictors in the research model were measured perceptually at a single point in time. In order to test for this bias, this study conducted the single factor test of Harman (Podsakoff and Organ, 1986). In this study, exploratory factor analysis of the measurement items for the five constructs in the survey reveals the seven factors explaining 24.45, 17.52, 16.64, 15.27, 15.20, and 10.92% of the total variance. These figures suggest that either a single factor emerges from the factor analysis or that a general factor accounts for the majority of the covariance in the independent and dependent vari-ables, suggesting that potential common method bias is not a threat herein for subsequent analysis.

The second limitation of this study is its general-izability, due to the highly delimited nature of the subject sample in a single country setting. The infer-ences drawn from such a sample in Taiwan may not be fully generalizable to employees from other countries in quite a different national culture. Indeed, given that the ways to build organizational trust and the beliefs about corporate citizenship may somewhat vary under differing cultures, the applications based on the empirical findings of this study to other countries should be used with caution. Cultural

psychologists suggest that national cultural differences may influence the perceived importance of corporate citizenship among organizational members. More specifically, Hofstede (1980) and Hofstede and Bond (1988) classify cultures based on five dimensions, including individualism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, masculinity and Confucian dyna-mism. For example, Australians and Americans are higher on individualism and masculinity and lower on uncertainty avoidance and power distance than peo-ple in Taiwan (e.g., Singhapakdi et al., 2001). Fur-thermore, previous research shows that core tenets of attachment theory are rooted in mainstream Western thought in depth and require fundamental change when applied to minority groups or other cultures (Rothbaum et al.,2000), suggesting that the empirical findings of this study should be applied to other countries with great caution.

The third limitation herein is about the content of our measurement items. Our survey asked employ-ees how they felt rather than how they performed. Thus, this study does not offer any direct evidence about employees’ actions and performance. Even if we expect that ‘‘when the organization enthusi-astically engages in corporate responsibility, its employees may be boosted to enthusiastically engage in their own individual responsibility in doing their work for the same,’’ we cannot prove it herein without any further survey.

Finally, due to the research scope that focuses on corporate citizenship, this study did not address other institutional variables, such as firm ownership, workplace cultures, working hours, organizational sizes, organizational structure, organizational leader-ship, profitability, etc. Specifically, a firm’s com-pensation plans (i.e., economic corporate citizenship) are related to firm ownership concentration, while size and profitability have been also linked to cor-porate citizenship (Mahoney and Thorn, 2006), making firm ownership concentration, size, and profitability be the three potential control variables for future research. Future studies should attempt to improve these shortcomings by including various control variables for further empirical tests and also by observing research subjects over time so that the genuine influences of perceived corporate citizenship on organizational trust and work engagement can be transparently revealed from a longitudinal aspect.

Conclusion

The most important idea in this study is that there is no ‘‘one size fits all’’ solution to enhance work engagement or organizational trust by a single dimension, such as performing economic citizenship. Management must understand that work engagement formation is a complex process owing to the under-lying nature of the antecedents of corporate citizen-ship and the mediator of organizational trust. It is important to keep in mind that work engagement is not just purely driven by employees’ personal needs, but also by the social needs accomplished by the organization. For example, in recent years, there has been a resurgence in the establishment of corporate foundations that focus on the solution of (future) social problems and on responding to unmet social needs (Westhues and Einwiller,2006).

According to a survey by Sirota Survey Intelli-gence, employees who are satisfied with their orga-nizational social responsibility are likely to be more positive, more engaged, and more productive than those working for less responsible organizations (Amble, 2009). Specifically, when employees are positive about their firm’s corporate citizenship, their work engagement rises to 86% (Amble,2009). When employees are negative about their firm’s corporate citizenship, only 37% are highly engaged (Amble, 2009). In summary, corporate citizenship and business success can hardly be separated. Firms that enhance their corporate citizenship is likely to boost their employees’ organizational trust and work engagement immensely.

Appendix: Measurement items Work engagement

WE1.: At my work, I feel full of energy; WE2.: In my job, I feel strong and vigorous; WE3.: I am enthusiastic about my job; WE4.: My job inspires me; WE5.: I feel happy when I am working intensely; WE6.: I am im-mersed in my work

Organizational trust

OT1.: I would be willing to let my firm have complete control over my future in the firm; OT2.: I would be

comfortable allowing the firm to make decisions that directly impact me, even in my absence; OT3.: Overall, I trust my firm

Perceived economic citizenship

EC1.: My firm supports employees who acquire addi-tional education; EC2.: My firm has flexible policies that enable employees to better balance work and personal life; EC3.: My firm provides important job training for employees; EC4.: My firm provides quality working environment for employees

Perceived legal citizenship

LE1.: The managers of my firm comply with the law; LE2.: My firm follows the law to prevent discrimination in workplaces; LE3.: My firm always fulfills its obligations of contracts; LE4.: My firm always seeks to respect all laws regulating its activities

Perceived ethical citizenship

ET1.: My firm has a comprehensive code of conduct in ethics; ET2.: Fairness toward co-workers and business partners is an integral part of the employee evaluation process in my firm; ET3.: My firm provides accurate information to its business partners; ET4.: We are rec-ognized as a company with good business ethics Perceived discretionary citizenship

DI1.: My firm gives adequate contributions to charities; DI2.: My firm sponsors partnerships with local schools or institutions; DI3.: My firm is concerned about respecting and protecting the natural environment; DI4.: My firm sponsors to improve the public well-being of society

References

Amble, B.: 2009, ‘Social Responsibility Boosts Employee Engagement’. Retrieved from http://www.management- issues.com/2007/5/9/research/social-responsibility-boosts-employee-engagement.asp.

Anderson, J. C. and D. W. Gerbing: 1988, ‘Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Rec-ommended Two-Step Approach’, Psychological Bulletin 103(3), 411–423.

Backhaus, K., B. Stone and K. Heiner: 2002, ‘Exploring the Relationship Between Corporate Social Perfor-mance and Employer Attractiveness’, Business and Society 41(3), 292–318.

Bakker, A. B. and E. Demerouti: 2008, ‘Towards a Model of Work Engagement’, Career Development International 13(3), 209–223.

Barkhuizen, N. and S. Rothmann: 2006, ‘Work Engagement of Academic Staff in South African Higher Education Institutions’, Management Dynamics 15(1), 38–46.

Baron, D.: 2001, ‘Private Politics, Corporate Social Responsibility and Integrated Strategy’, Journal of Eco-nomics and Management Strategy 10(1), 7–45.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., B. A. Cudmore and R. P. Hill: 2006, ‘The Impact of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Behavior’, Journal of Business Research 59(1), 46–53.

Becker, T. E.: 1998, ‘Integrity in Organizations: Beyond Honesty and Conscientiousness’, Academy of Manage-ment Review 23(1), 154–161.

Bowlby, J.: 1973, ‘Attachment and Loss’, in Separation: Anxiety and Anger, vol. 2 (Basic Books, New York). Brammer, S. and A. Millington: 2003, ‘The Effect of

Stakeholder Preferences, Organizational Structure and Industry Type on Corporate Community Involve-ment’, Journal of Business Ethics 45(3), 213–226. Brammer, S., A. Millington and B. Rayton: 2007, ‘The

Contribution of Corporate Social Responsibility to Organizational Commitment’, International Journal of Human Resource Management 18(10), 1701–1719. Carroll, A. B.: 1979, ‘A Three-Dimensional Conceptual

Model of Corporate Performance’, Academy of Man-agement Review 4(4), 497–505.

Cartwright, S. and C. L. Cooper: 2009, The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well-Being (Oxford University Press, Oxford).

Chughtai, A. A. and F. Buckley: 2007, The Relationship Between Work Engagement and Foci of Trust: A conceptual analysis. Proceedings of the 13th Asia Pacific Management Conference, Melbourne, Aus-tralia, pp. 73–85.

Chughtai, A. A. and F. Buckley: 2008, ‘Work Engage-ment and its Relationship with State and Trait Trust: A Conceptual Analysis’, Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management 10(1), 47–71.

Chughtai, A. A. and F. Buckley: 2009, ‘Linking Trust in the Principal to School Outcomes: The Mediating Role of Organizational Identification and Work Engagement’, International Journal of Educational Man-agement 23(7), 574–589.

Dawkins, J.: 2004, The Public’s Views of Corporate Responsibility 2003 (Mori, London, UK).

De los Salmones, M. D. M. G., A. H. Crespo and I. R. del Bosque: 2005, ‘Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Loyalty and Valuation of Services’, Journal of Business Ethics 61(4), 369–385.

Dyer, J. H. and W. Chu: 2003, ‘The Role of Trust-worthiness in Reducing Transaction Costs and Improving Performance: Empirical Evidence from the United States, Japan, and Korea’, Organization Science 14(1), 57–68.

Fay, D. and H. Luhrmann: 2004, ‘Current Themes in Organizational Change’, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 13(2), 113–119.

Fornell, C. and D. F. Larcker: 1981, ‘Evaluating Struc-tural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error’, Journal of Marketing Research 18(1), 39–50.

Fukuyama, F.: 1995, Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity (The Free Press, New York). Gill, A. S.: 2008, ‘The Role of Trust in Employee–

Manager Relationship’, International Journal of Con-temporary Hospitality Management 20(1), 98–103. Gonza´lez-Roma, V., W. B. Schaufeli, A. Bakker and

S. Lloret: 2006, ‘Burnout and Engagement: Indepen-dent Factors or Opposite Poles?’, Journal of Vocational Behaviour 68, 165–174.

Grayson, D. and A. Hodges: 2004, Corporate Social Opportunity: Seven Steps to Make Corporate Social Responsibility Work for Your Business (Sheffield Pub-lishing, Salem, WI).

Hardy, G. E. and M. Barkham: 1994, ‘The Relationship Between Interpersonal Attachment Styles and Work Difficulties’, Human Relations 47(3), 263–281. Hofstede, G.: 1980, ‘National Cultures in Four

Dimen-sions: A Research Based Theory of Cultural Differences Among Nations’, International Studies of Management and Organization 13(1/2), 46–74.

Hofstede, G. and M. H. Bond: 1988, ‘The Confucious Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth’, Organizational Dynamics 16(4), 5–21. Joyner, B. E. and D. Payne: 2002, ‘Evolution and

Implementation: A Study of Values, Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility’, Journal of Busi-ness Ethics 41(4), 297–311.

Knapp, J. C.: 2007, Leaders on Ethics: Real-World Perspec-tives on Today’s Business Challenges (Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT).

Keller, T. and R. Cacioppe: 2001, ‘Leader-Follower Attachments: Understanding Parental Images at Work’, Leadership & Organization Development Journal 22(2), 70–75.

Lamberti, L. and E. Lettieri: 2009, ‘CSR Practices and Corporate Strategy: Evidence from a Longitudinal Case Study’, Journal of Business Ethics 87(2), 153–168.

Luo, X. and C. B. Bhattacharya: 2006, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value’, Journal of Marketing 70, 1–18.

Maerki, H. U.: 2008, ‘The Globally Integrated Enterprise and its Role in Global Governance’, Corporate Gover-nance 8(4), 368–374.

Mahoney, L. S. and L. Thorn: 2006, ‘An Examination of the Structure of Executive Compensation and Cor-porate Social Responsibility: A Canadian Investiga-tion’, Journal of Business Ethics 69(2), 149–162. Maignan, I. and O. C. Ferrell: 2000, ‘Measuring

Cor-porate Citizenship in Two Countries: The Case of the United States and France’, Journal of Business Ethics 23(3), 283–297.

Mathews, C. G. G.: 2007, ‘Thinking about leadership – leaders for tomorrow’, in The Proceedings of the 2nd National Conference on Global Competition and Competi-tiveness of Indian Corporates (Indian Institute of Man-agement, Kozhikode, India).

Maxfield, S.: 2008, ‘Reconciling Corporate Citizenship and Competitive Strategy: Insights from Economic Theory’, Journal of Business Ethics 80(2), 367–377. Mayer, R. C. and J. H. Davis: 1999, ‘The Effect of the

Performance Appraisal System on Trust for Manage-ment: A Field Quasi-Experiment’, Journal of Applied Psychology 84(1), 123–136.

Morrison, E. E., G. C. Burke III and L. Greene: 2007, ‘Meaning in Motivation: Does Your Organization Need an Inner Life?’, Journal of Health and Human Services Administration 30(1), 98–115.

Nelson, D. L. and J. C. Quick: 1991, ‘Social Support and Newcomer Adjustment in Organizations: Attachment Theory at Work?’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 12(6), 543–554.

Nelson, L. S.: 1999, ‘Contriving an Unavailable Significance Level’, Journal of Quality Technology 31(3), 351–353. Podsakoff, P. M. and D. W. Organ: 1986, ‘Self-Reports

in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects’, Journal of Management 12(4), 531–544.

Reynolds, N., A. Diamantopoulos and B. B. Schlegelmilch: 1993, ‘Pretesting in Questionnaire Design: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for Further Research’, Journal of the Market Research Society 35(2), 171–182. Robinson, S. L.: 1996, ‘Trust and Breach of the

Psy-chological Contract’, Administrative Science Quarterly 41, 574–599.

Rothbaum, F., J. Weisz, M. Pott, K. Miyake and G. Morelli: 2000, ‘Attachment and Culture: Security in the United States and Japan’, American Psychologist 55(10), 1093–1104.

Sable, P.: 2008, ‘What is Adult Attachment?’, Clinical Social Work Journal 36(1), 21–30.

Salanova, M., S. Agut and J. M. Peiro´: 2005, ‘Linking Organizational Resources and Work Engagement to Employee Performance and Customer Loyalty: The Mediating role of Service Climate’, Journal of Applied Psychology 90, 1217–1227.

Schaufeli, W. B., A. B. Bakker and M. Salanova: 2006, ‘The Measurement of Work Engagement with a Short Questionnaire: A Cross-National Study’, Educational and Psychological Measurement 66, 701–716.

Schoorman, F. D., R. C. Mayer and J. H. Davis: 2007, ‘An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust: Past, Present, and Future’, Academy of Management Review 32(2), 344–354.

Shen, C. H. and Y. Chang: 2009, ‘Ambition Versus Conscience, Does Corporate Social Responsibility Pay Off? The Application of Matching Methods’,Journal of Business Ethics 2009(88), 133–153.

Siegel, D. S. and D. F. Vitaliano: 2007, ‘An Empirical Analysis of the Strategic Use of Corporate Social Responsibility’, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 16(3), 773–792.

Simmons, J.: 1990, ‘Participatory Management: Lessons from the Leaders’, Management Review 79(12), 54–58. Singhapakdi, A., K. Karande, C. P. Rao and S. J. Vitell: 2001, ‘How Important are Ethics and Social Respon-sibility? A Multinational Study of Marketing Profes-sionals’, European Journal of Marketing 35(1/2), 133–153. Spreitzer, G. M. and A. K. Mishra: 2002, ‘To Stay or to Go: Voluntary Survivor Turnover Following an Organizational Downsizing’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 23, 707–729.

Tan, H. H. and A. K. H. Lim: 2009, ‘Trust in Coworkers and Trust in Organizations’, Journal of Psychology 143(1), 45–66.

Tan, H. H. and C. S. F. Tan: 2000, ‘Toward the Dif-ferentiation of Trust in Supervisor and Trust in Organization’, Genetic, Social and General Psychology Monographs 126(2), 241–260.

Townsend, P. and J. Gebhardt: 2008, ‘Employee Engagement – Completely’, Human Resource Manage-ment International Digest 16(3), 22–24.

Turker, D.: 2009, ‘Measuring Corporate Social Respon-sibility: A Scale Development Study’, Journal of Business Ethics 85(4), 411–427.

Waddock, S. E. and S. B. Graves: 1997, ‘The Corporate Social Performance-Financial Performance Link’, Strategic Management Journal 18(4), 303–319.

Westhues, M. and S. Einwiller: 2006, ‘Corporate Foun-dations: Their Role for Corporate Social Responsi-bility’, Corporate Reputation Review 9(2), 144–153. Weyzig, F.: 2009, ‘Political and Economic Arguments

Proposition Regarding the CSR Agenda’, Journal of Business Ethics 86(4), 417–428.

Williams, L. L.: 2005, ‘Impact of Nurses’ Job Satisfaction on Organizational Trust’, Health Care Management Review 30(3), 203–211.

Williamson, O. E.: 1985, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (Free Press, New York).

Wood, D.: 1991, ‘Corporate Social Performance Revis-ited’, Academy of Management Review 16(4), 691–718.

Zahra, S. A. and M. S. LaTour: 1987, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Organizational Effectiveness: A Multivariate Approach’, Journal of Business Ethics 6(6), 459–467.

Institute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, ROC E-mail: jacques@mail.nctu.edu.tw