國立交通大學

英語教學研究所碩士論文

A Master Thesis Presented to Institute of TESOL National Chiao Tung University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Arts

初探台灣以英文為外語之學童的口語敘事發展:以中文與英文故事

「青蛙,你在哪裡?」為例

Narrative Development of Taiwanese EFL Children: A First Glance at the

Children’s Story “Frog, Where are you?” in English and Chinese

研究生:林佳樺 Graduate: Chia-Hua Lin 指導教授:林律君博士 Advisor: Dr. Lu-Chun Lin

中華民國 九十八年 六月 June, 2009

論文名稱:初探台灣以英文為外語之學童的口語敘事發展:以中文與英文故事 「青蛙,你在哪裡?」為例 校所組別:國立交通大學英語教學研究所 畢業時間:九十七學年度第二學期 指導教授:林律君博士 研究生:林佳樺 中文摘要 有鑑於外語學習在台灣日漸興盛,兒童語言習得(children’s language acquisition)已是當下廣為探究的領域之一。為深入了解兒童語言習得的過程及發 展,口語敘事能力(oral narrative ability)儼然成為不可或缺的一環。因此,孩童 的口語敘事發展(oral narrative development)更是與其能力的培養息息相關。

本論文主要在探討台灣以英文為外國語言的兒童,其口語敘述之發展,主要 是針對敘事結構(narrative structure),又稱故事結構(story grammar),做深入的分 析及探究。除了探討不同年齡層孩童之間的敘事發展之外,亦比較跨語言的敘事 差異。

本研究對象是 21 名全美語幼稚園學童(English-immersion kindergarten) 及 23 名參與該機構之課後輔導(after-school program)的國小學童。這些孩童根據研究者 所提供的一本無字圖畫書(Frog, Where Are You? Mayer, 1969),分別以中文和英 文敘述出書中的內容。其敘述的內容被進一步轉譯,並針對故事結構成分(story grammar components)及故事結構等級(story grammar levels)予以分析歸類。

研究結果顯示,大部分學童的敘述能力皆符合既有的分級;以學齡前學童而 言,主要都被分類至三個等級中:(1)行為順序(action sequence),(2)反應順序 (reactive sequence),以及(3)簡易情節(abbreviated episode)。然而,國小學童的表 現,相較學齡前孩童,包括更多的層級:(1)反應順序(reactive sequence),(2)簡易 情節(abbreviated episode),(3)完整情節(complete episode),(4)複雜情結(complex episode),以及(5)嵌入性情節(embedded episode)。

再者,研究結果亦顯示了跨年紀及跨語言的差異。以跨年紀的敘事發展而 言,學齡前學童相較於國小學童者,有以下的幾點敘事特徵:(1)較無法依照書 中的正確順序將情節描述出來,(2)較容易說出錯誤的資訊及內容,(3)較不容易 洞察主角的情緒狀態,(4)說出較多重覆的句子,以及(5)無法像學齡孩童一樣, 使用較複雜的句子及故事慣用語式 (formulaic expression),來開啟故事及做結 尾。在跨語言的差異方面,兩組學童的中文故事,相對於英文故事而言,較能提 供正確的資訊內容以及較少說出重覆的句子。 此外,本研究希望藉由此研究成果,協助英語學習者發展敘事能力。並且, 能對關切及投身於語言教學的老師及家長們,有所助益。

ABSTRACT

The purpose of the present study was to examine the narrative performance of Taiwanese EFL children in both Chinese and English. The developmental changes in children’s stories across two age groups and the similarities and differences of children’s story structures in the two languages were explored.

Twenty-one children from an English-immersion kindergarten program and 22 elementary-school children from an English afterschool program participated in this study. Both groups of children were asked to tell a story in Chinese and English respectively from a wordless picture book, Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969). Children’s stories were segmented into modified C-units and were further analyzed using the story grammar components (Stein & Glenn, 1979). Each of the children’s story was also categorized into different story grammar levels (Westby et. al., 1984; 1986).

The overall descriptive analyses showed that the Taiwanese EFL children of the present study told their Chinese and English stories roughly matched Westby et al.’s eight-stage story grammar (1984; 1986). The preschool children’s narratives mainly fell into three levels: action sequence, reactive sequence, and abbreviated episode; in contrast, the school-aged children’s story levels were more varied, ranging from the simpler story structure such as reactive sequence to more complex structure such as abbreviated episode, complete episode, complex episode, and embedded episode.

The cross-age comparisons revealed that the preschool children had lesser ability than the school-aged children in the following aspects: (1) story sequencing, (2) correct information provided, (3) the awareness of psychological states, (4) effective use of repetitions, and (5) story opening and ending.

Chinese and English. The results showed that the children’s English stories contained more incorrect information, and the preschool English stories showed extensive but futile instances of repetitions.

In view of the findings, the present study presented a preliminary investigation that examined Taiwanese EFL children’s narrative development in Chinese and English and hoped to provide a preliminary understanding for teachers and parents when they are involved in children’s narrative and language development.

Acknowledgements

I can never imagine I could ever finish my master’s thesis. In the beginning, it was almost mission impossible for me. However, something magic happened. Full of joyfulness and ecstasy, I would like to show my sincere gratitude to all people

surrounding me.

First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest appreciation toward my advisor, Dr. Lu-Chun Lin (林律君博士), for her patience guiding and revising my thesis over and over again. Her profound feedback and insightful suggestions inspire my interest in the field of children’s narrative research. So many things I have learned from her, including the approaches of conducting a research, the techniques of

analyzing the results, and the most important of all, the wise skills to lead my thesis into a more academic and professional degree. It has been always my honor to have Dr. Lin as my advisor.

In the meanwhile, I would also like to show my profoundest gratitude to my committee members, Dr. Wei-Yu Chen (陳瑋瑜博士) and Dr. Rong-Lan Yang (楊榮 蘭博士), for the remarkable comments and precious advices. This thesis could not be better without their complete support. Furthermore, for all professors and faculties at the TESOL Institute of NCTU, I would like to show my genuine gratefulness.

In addition, my appreciation is extended to the CEO and faculties of the English immersion kindergarten for thoroughly assistance for my data collection. I want to especially thank to Teacher Bee and Teacher Lace for their extra guidance. More importantly, many thanks to those children recruited in the study. Without their participation, my thesis would not go smoothly.

For my dearest friends and classmates, I am extremely indebted to all of you! Many thanks to my dearest friends Catosline, Ko, Ken, Leorry, Mavis, Winnie, Louie,

Karen, Elisa, Oligo, and especially Hannah, who are always keep me company and give me courage. I also have to acknowledge my debt to Ji-Xian Zhong, Xian-Yi Lin, and most important of all, Zhi-Sheng Fan, who always provide me valuable

suggestions and show their most concern about me.

Last but not least, I want to devote my earnest love to my parents, Shen-Yuan Lin (林勝源) and Xue-Zhen Xie (謝雪珍). I could not help but say, “Dad and Mon, I make it!” My parents are always with me and give me spiritual support whenever I felt frustrated and unconfident. Without them, it is never possible for me to go through all these challenges. Besides, my dear brothers, I am so grateful for your

encouragements. I missed the time seeing your heartwarming messages through MSN or on Blog. I really need that! Thank everyone who ever expressed their concern about me and did me a favor. Thank you all!

TABLE OF CONTENTS 中文摘要...i ABSTRACT………..iii ACKNOWLEDMENTS……….…v TABLE OF CONTENTS………..…………...vii LIST OF TABLES………...……...x LIST OF FIRURE………...…….……….xi LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS………...xii

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION……….1

Purpose and the Significance of the Study……….4

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW………..7

The Importance of Children’s Narrative Development………..7

Children’s Narrative Development………...12

Monolingual Children’s Narrative Development……….12

Bilingual Children’s Narrative Development………...14

Narrative Studies in Taiwan……….16

Story Grammar Analysis and Pertinent Studies………...19

CHAPTER THREE METHOD………26

The Study……….26

Participants………...26

English-immersion Kindergarten……….27

After School Program………...28

Materials………...28

Data Collection and Procedures………...29

Transcription Reliability………...……32

Data Analyses………...33

Story Grammar Analyses………..33

Coding Reliability……….………35

Levels of Story Grammar………..35

CHAPTER FOUR RESULTS ……….39

Descriptive Analyses of Children’s Stories………..39

Productivity of Narratives………40

Analyses of Children’s Chinese and English Story………..42

Comparisons between Preschool Children’s and Schooled-aged Children’s Stories………...44

Comparisons between Children’s Chinese and English Stories………...59

Summary………..60

CHAPTER FIVE DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION……….62

Narrative Productivity of the Children’s Stories………..62

Levels of Story Grammar……….63

Comparison between the Preschool and School-aged Children’s Stories………65

Comparison between the Children’s Chinese and English Stories………...69

Pedagogical Implications of the Study……….71

Limitations of the Present Study and Suggestions for Future Research………..72

REFERENCES……….74

APPENDICES………..83

Appendix A: Consent Form for the Kindergarten Administration: Chinese…………84

Appendix B: Informed Consent Letter for Parents: Chinese ………..86

Appendix D: Parental Socioeconomic Information ………89 Appendix E: List of Transcription and Coding Conventions Based on SALT……….91 Appendix F: Story Grammar Analysis Form ……….……..92 Appendix G: An Example of One Preschool-aged Child’s Story Grammar Analyses.93 Appendix H: An Example of One School-aged Child’s Story Grammar Analyses….96 Appendix I: Examples of Children’s Frog Stories………...………98

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Story Structure Components………34 Table 2 Progression of Narrative Development ………..36 Table 3 Means and Standard Deviations of Number of C-units Produced by Preschool

and School-aged Children Respectively in Chinese and English Narratives...40

Table 4 Means and Standard Deviations of Number of Episodes Produced by

Preschool and School-aged Children Respectively in Chinese and English Narratives……….42

Table 5 Levels of Story Grammar of Preschool Children’s and School-Aged

Children’s Chinese and English Stories………...44

Table 6 Comparisons between Preschool and School-aged Children’s Stories……...45 Table 7 Examples of Ways the Preschool Children Used to Open the Chinese and

English Stories………..56

Table 8 Examples of Ways the School-aged Children Used to Open the Chinese and

English Stories………57

Table 9 Examples of Ways the Preschool Children Used to Conclude the Chinese and

English stories………58

Table 10 Examples of Ways the School-aged Children Used to Conclude the Chinese

and English stories……….59

LIST OF FIGURE

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS A Attempt AE AS Abbreviated Episode Action Sequence B Behavior C Consequence CE Complete Episodes

CXE Complex Episodes

DS Descriptive Sequence E Ending EE Embedded Episode ID Isolated Description IE Initiating Event IP Internal Plan IR IS Internal Response Internal State R Resolution/Reaction RS Reactive Sequence S Setting

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION

Narratives play an important role in human communication for thousands of years. Ancient people conveyed their wisdom and culture through narrating stories to next generations. We narrate to entertain, to explain, to express, or to reflect on our own experiences and the experiences of others. The study of narrative is the study of the ways humans experience the world (Connelly & Clandinin, 1990).Through narratives, we come to realize ourselves and others. It is the basic scheme of thought that happens all around our lives. According to Hardy (1978), “…we dream in narrative, daydream in narrative, remember, anticipate, hope, despair, doubt, plan, revise, criticize, construct, gossip, learn, hate and love by narrative” (p. 13).

In addition, competence in narration is an essential skill for everyone in any community. Although almost everyone can achieve sufficient competency in daily conversation, there are still large number of people with limited skills in narrative language essential for better literacy and school performance. It is critical that educators and researchers understand the nature of narratives. Given the significance of narratives, abundant studies in this area have been undertaken.

Narrative is a text or discourse composed through signed, written or spoken medium, and the production of a narrative includes the coordination of three cognitive domains: linguistic, pragmatic, and cognitive abilities. First of all, linguistic devices are performed within and across sentences, while the bigger discourse units could enclose episodes or settings (Peterson & McCabe, 1990). Second, with regard to pragmatic abilities, which are recognized to contribute to overall functional and communicative competence (Manochioping, Sheard, & Reed, 1992), Hudson and Shapiro (1991) further considered them as central in producing and comprehending

narratives. Their high emphasis on pragmatic abilities also prompted the awareness of being a better conversation partner or conformed to the addressee’s information needs. In other words, the concept reflects the fact that to become a competent speaker requires more than proficiency in grammar, vocabulary or native-like pronunciation (e.g., linguistic abilities). Moreover, narratives are not only a reflection of speakers’ linguistic ability, but could also reveal their understanding of the world. With respect to cognitive abilities, performance such as working memory or information processing of continuously amounts of information is also involved (Eisenberg, 1985). A relevant concept about cognitive abilities which is worth mentioning is to understand that, narratives like stories require the operation of both the local (microstructure) and global (macrostructure) level. The local or microstructure level refers to the

presentation of linguistic abilities, such as the use of connectives and the expression of causality. On the other hand, the global or macro level refers to the content or conceptual level, usually including the overall structure and organization of a story (Hudson & Shapiro, 1991). In addition, people from different cultures might differ in the perceptions, conceptualizations, or interpretation of the world due to the different abilities and understanding in cognitive processing.

Studies of narratives have become an emerging filed of research that has attracted great attention of researchers from diverse disciplines, including educators, linguists, philosophers, or psychologists. Different disciplines analyze narratives focusing on different aspects, and studies on children’s narrative development have been of major concerned in the recent years.

A growing number of studies are now available to provide better understanding of children’s narrative development. For example, research on children’s narrative development across different age groups has been extensively examined (Applebee,

1978; Miller & Sperry, 1988; Umiker-Sebeok, 1979). Similarly, studies on bilingual children’s narrative performances are also getting considerable attention (Barley & Pease-Alvarez, 1997; Dart, 1992; Guiterrez-Clellen, 2002; Minaya Portella, 1980; Silliman, Huntley Bahr, Brea, Hnath-Chisolm, & Mahecha, 2002).

Given the importance and need of examining children’s narrative development, the ways of assessing narrative production is also an issue worth discussing. Narrative assessment provides an avenue to evaluate individual’s schema knowledge, social cognition, and linguistic discourse skills (Hedberg & Westby, 1993). Among various assessment systems (e.g., narrative analysis systems), story grammar analysis is commonly used to examine children’s story structure. Story grammar is the story structure or the set of rules for making up a story (Bamberg, 1987). According to Hedberg and Westby (1993), story grammar analysis examines children’s ability to use the macrostructure elements in telling stories. In the meanwhile, information about content or organization is also provided. It also shows the natural components of a story, which includes the interrelationships and characters within the story.

Various kinds of story grammar models have been developed. Among them, two most common models will be illustrated. One is Labov’s definition (1972)of a well-formed narrative structure; the other is Stein and Glenn’sstory grammar model (1979), which illustrated that a model of story grammar has some related episodes. The episodes contain components that consist of setting, initiating events, reactions and attempts, consequence, reaction or resolution, and ending. Most studies

examining children’s narrative development across languages and ages, however, used the story grammar model proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979) (e.g., Applebee, 1978; Gillam, McFadden, & van Kleeck, 1995; Hughes, McGillivray, & Schmidek, 1997; Mandler & Johnson, 1977; Westby, 1984), and several other studies were also done to

investigate children with language disorders using the story grammar model (Gillam, McFadden, & Van Kleeck, 1995; Merritt & Liles, 1987; Roth & Spekman, 1986). For example, Merritt and Liles (1987) used this story grammar model to analyze

children’s narratives in their study, which aimed to examine and compare the narrative performances between language-impaired children with normal children.

Story grammar analysis is not only used to examine children’s narrative

development or abilities, it has also been adopted as an intervention or teaching tool. In Taiwan, some studies have conducted the story structure teaching to learning situation, and the results showed that story structure teaching could enhance preschool children’s reading comprehension and perception (Cheng, 2006; Hung, 2007; Liu, 2007).

Although numerous studies on narrative development of monolingual and bilingual children and of many languages have been conducted, relatively scant research examined narrative development of Taiwanese children who are learning English as a foreign language (EFL) at an early age. Among the limited studies examining Taiwanese children’s narratives, some focused on children’s referential strategies or abilities in either elementary or preschool levels (Sung, 2004; Yang, 2008), while some paid attention to preschoolers’ narrative structure in personal storytelling (Shu, 2007). The present study differed from prior studies by specifically exploring the developmental changes and cross-language differences in the narrative structure of Taiwanese children from two age groups.

Purposes and the Significance of the Study

The goal of this study, as briefly mentioned above, was to document Taiwanese EFL children’s oral narratives in Chinese and English. More specifically, the

developmental changes in children’s stories and cross language differences were explored. The following research questions were addressed in this proposed thesis study:

1. How do Taiwanese preschool children’s Chinese and English stories differ from school-aged children’s stories in terms of macrostructures?

2. How do Taiwanese children’s Chinese stories differ from their English stories?

To answer these two questions, two groups of Taiwanese EFL children participated in this study, and their Chinese and English narratives were collected using the wordless picture book, Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969). Story grammar model proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979) was used to analyze their stories. The answer to these questions will provide preliminary pictures of EFL children’s

narrative development of story structures in their native as well as foreign languages. It is also hoped that the results will inform EFL teachers regarding the implications of incorporating narrative skills in teaching English.

The thesis consists of five chapters and is organized in the following manner. Chapter One discusses the importance of research in narrative development, briefly introduced the history of story grammar research. The purpose of the study and the two research questions are also stated in this chapter. Chapter Two will review related literature on children’s narrative development, focusing on the two major groups of research participants, that is, monolingual and bilingual children. In addition, a detailed definition of story grammar and previous studies utilizing story grammar analysis will be illustrated. Chapter Three will describe the methodology, including participants, materials, data collecting procedures, coding method, and data analysis. Chapter Four will present the descriptive results of the study. Chapter Five will

discuss the results and provide conclusions. The implications and limitations of the present study as well as the suggestions for further research will also be included.

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW

The purpose of the present study was to examine the macrostructure of EFL children’s narrative development in two languages. The first section of this chapter highlighted the importance of narrative development. The second section reviewed the studies on the narrative development of monolingual and bilingual children. Finally, detailed descriptions of a story analysis system, namely story grammar analysis (Labov, 1972; Stein & Glenn, 1979) were introduced. Examples of narrative studies using story grammar analysis will also be presented.

The Importance of Children’s Narrative Development

One of the more intriguing issues prevailing throughout the last few decades of language developmental research is children’s narrative development. The study of children’s narrative development is viewed as an important aspect with which to manifest a broader and clearer understanding of the developmental process of language acquisition (Karmiloff-Smith, 1986). Over the past few years, the focus of studies about children’s narrative development has shifted from the micro-level (e.g., pronunciation, vocabulary, or grammar) to the investigations of extended discourse ability (e.g., the ability to use conjunctions to link different sentences).According to Karmiloff-Smith (1986), preschool and elementary school children’s extended discourseability could be observed , and among the different abilities discussed in extended discourse, oral narrative ability is the most commonly examined.

account for the increasing attention paid to children’s narrative development. First, according to Chang (2006), there is a relationship between children’s narrative abilities and their literacy skills. Second, children’s language developmental problems could be predicted by examining their narratives. In addition, children’s stories could show their thoughts, and parents or educators could understand what the children are thinking by analyzing their narratives. Last, narratives are often viewed as a way to socialize with others.

It has been proved that there is a positive correlation between children’s narrative skills and their literacy ability. Some studies have shown that children who are good at narrating will most likely perform better in writing and reading (Richard & Snow, 1990; Snow, 1983; 1991; Snow & Dickinson, 1991). A recent large-scale study by Miller et al. (2006) provided evidence for this statement. In this study, they examined whether oral language collected from bilingual children could predict reading achievement both within and across languages. There were 1,531 Spanish-speaking children participating in this study. Children’s oral language skills, such as lexical, syntactic, language fluency, and discourse skill, were examined using the wordless picture book Frog, Where Are You

(Mayer,1969). During the data collection procedure, the children were asked to retell the story whose prescripted version had been told by the examiner earlier. The children had to tell the story twice: the first time children were tested in Spanish, which was supposedly their stronger language; approximately 1 week later, the same procedure was repeated in English. The results revealed that Spanish and English oral language measures contribute to reading within and across languages. On the other hand, children‘s reading proficiency could be predicted by their oral language skills in both languages.

Numerous studies also demonstrated the correlation among children’s narrative language skills, their literary acquisition and academic performance (Leadholm & Miller, 1995; Paul & Smith, 1993; Torrance & Olson, 1984). For example, the study by Huang and Shen (2003) pointed out that children with higher linguistic ability could perform better in narrating than children with weaker linguistic ability at the same or older ages.The studies reviewed are in line with the findings of Chang’s study (2006) that there are relationship between children’s narrative ability and their academic performances.

According to Chang (2006), assessing children’s narrative production may have clinical utility as a criterion-reference measure. Children’s narratives could manifest possible and critical problems in their language development. Several studies have noted that linguistic developmental problems could be predicted by or examined through analyzing children’s narratives (Gutierrez-Clellen, 2002; Norbury & Bishop, 2003; Zou & Cheung, 2007). In other words, narratives have become one of the important tools to identify children with language disorders (Norbury & Bishop, 2003; Qi, 2001; Zou & Cheung, 2007).

As Norbury and Bishop (2003) pointed out, analyzing narratives is a good method to assess linguistic abilities of older children with communication

impairments and with autistic spectrum disorders. In this study, they first mentioned the importance of narrative skills in typical development, and they further explored the relationship between structural language ability and pragmatic competence in children’s narratives. The wordless picture book Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969) was used to generate children’s narratives during procedures. The outcome showed that children with specific language impairment and autistic disorder made more syntactic errors, and autistic children were more likely to produce ambiguous

references in telling stories. Through their study, evidence could be shown to prove that children with language disorders can be identified through analyzing their narratives.

In the third aspect, Chang (2006) suggested that stories children tell not only reveal their language abilities, but also reflect their thoughts. Children tend to express their life experiences or their thoughts and ideas by telling a story, and it is also claimed that personal storytelling provides resources for young children as they express and understand who they are (Bruner, 1986; Engel, 1995; Nelson, 1986; 1989). Moreover, there may be a “special affinity” between narratives and selves, which refers to narratives, such as personal storytelling, play a significant role in the process of self-construction (Miller, Potts, Fung, Hoogstra, & Mintz, 2003). Consequently, by analyzing children’s stories, their inner thoughts could be noticed and understood.

The fourth benefit for examining children’s narrative development is the interactive function of narratives (Chang, 2006). Narratives are often used to understand the process of socialization and enculturation. They are also considered “an arena for the social construction of autonomous selves” (Wiley, Rose, Burger, & Miller, 1998, p. 833). People from different cultures or societies might perform differently in narrating, and hence children’s narrative abilities and styles tend to reflect their cultural or social variations (Blum-Kulka & Snow, 1992; Heath, 1982; McCabe, 1996). An important study determined the functions of personal

storytelling and its relationship with socialization, in the context of Taiwanese and European American families (Miller, Wiley, Fung, & Liang, 1997; Minami, 1996). The focal children’s average age was 2; 6. More than 200 stories about the past experiences were analyzed for their content, function, and structure. The findings

showed that personal storytelling manifests overlapping but distinct socializing functions in two cultural cases. The most important and interesting finding of these studies was that Chinese families tended to convey moral and social standards because of Confucian tradition in their personal storytelling. European American families, however, viewed storytelling as a medium of entertainment. As a result, the study suggested that storytelling functions differently in different cultures as well as among children from different backgrounds.

As suggested by Gutierrez-Clellen and Quinn (1993), “storytelling is never context-free, and oral narratives are created in contextualized interactions” (p. 2). In their study, they examined issues in assessing narratives produced by children from diverse cultural and ethnic backgrounds, and identified the differences as well as taught children the context-specific narrative rules valued in American schools. In their study, they argued that narrative contextualization processes are

culture-specific and must be considered in assessment.In another study, Gee (1991) further indicated that analyzing children’s narratives might be also a significant way to understand their beliefs, presumptions, norms, and values adopted from the cultural environments.

The literature reviewed above centered on the importance of children’s narrative development. These studies also provided important implications for future studies on narrative development of non-mainstream children (e.g., bilingual children). Therefore, the significance of examining children’s narrative

Children’s Narrative Development

Various studies have been done to examine children’s narratives skills in different languages. In the following section, literature on children’s narrative development will be further discussed with respect to monolingual and bilingual children, and the narrative studies on Taiwanese children will also be provided.

Monolingual Children’s Narrative Development

Most of the studies on children’s narrative development paid attention to monolingual children’s narratives. Several studies have focused on monolingual children’s narrative growth and development at different ages (Applebee, 1978; Miller & Sperry, 1988). Miller and Sperry (1988) indicated that children start to tell stories of their personal experiences as early as two years of age (Miller & Sperry, 1988). Applebee’s (1978) studyfurther indicated that children are able to tell fantasy narratives before going to school. However, these studies suggested that the narratives produced at this age are relatively shorter, simpler, and more fragmented. Furthermore, Stein and Glenn (1979) indicated that children succeed in telling short and coherent stories with a problem-action-consequence structure by the early primary grades; in other words, children can structure stories around a problem, an attempt to solve the problem, and also a consequence of the story.

In addition to the studies mentioned above, other research has investigated children’s narrative development through analyzing their usages of referential cohesion. Referential cohesion, which is necessary for understanding the narrative events, is what narrators used to introduce characters, props, and places in a story (Halliday & Hasan, 1976). Umiker-Sebeok (1979) pointed out that children showed significant growth in the complexity of their narratives at three and four years of

age. In addition, children at this stage acquired cohesive devices, such as anaphoric reference (e.g., pronouns) and connectives (e.g., and, then). Other similar studies were further conducted to prove that most children at five or six years of age were able to produce a longer and more complete story. Compared to children of three or four years old, five or six-year-old children had better ability in choosing time or referential usages (Bamberg, 1987; Hickman, 1980; Karmiloff-Smith, 1980; 1981). More recently, Gutierrez-Clellen and Heinrichs-Ramos (1993) examined children’s development of referential cohesion based on the referential devices. Participants were 46 Spanish-speaking children ages four, six, and eight. A short silent movie “Frog Goes to Dinner” (Phoenix Films) was used to collect the narratives. The participants saw the movie in advance and were later asked to tell what happened in the movie. The results manifested that as children got older, they tended to use more elliptical references, which involve the omission of a word or phrase that can be presupposed form the previous text (e.g., Where is his? /pen/),and appropriate phrases to refer to places in storiesand their usages of ambiguities andfalse additions also reduced over time.

Apart from English-speaking children’s narrative development reviewed, Minami (1996) examined Japanese children’s narrative development through analyzing their oral narratives. Twenty Japanese preschool children with average ages of four and five years participated in the study. Their oral personal narratives were analyzed and the results showed that four-year-old Japanese children had more difficulties than five-year-olds in presenting nonsequential information in their stories, such as evaluation, and children at age of five also tried to use adult-like narratives. In addition, the study clearly indicated that children’s narratives ability showed rapid development during the preschool years.

Although substantial studies have focused on monolingual children’s narrative development in many languages, those of bilingual children also get great

importance and will be discussed further.

Bilingual Children’s Narrative Development

Some studies on narrative development concentrate on monolingual children, while others investigate bilingual children’s narrative development. Limited studies on bilingual children have argued that children tend to produce narratives

differently in each of their two languages, and several researchers also suggested that linguistic differences might be one of the factors that cause different narrative performance (Barley & Pease-Alvarez, 1997; Dart, 1992; Guiterrez-Clellen, 2002; Minaya Portella, 1980; Silliman, Huntley Bahr, Brea, Hnath-Chisolm, & Mahecha, 2002).

Fiestas and Pena (2004) conducted a study to examine Spanish-English bilingual children’s production of narrative samples. The purpose of the study was to investigate the effect of the language on children’s production. Twelve children raging in age from 4; 0 to 6; 11 were asked to tell a story under two elicitation

conditions: one using Mayer’s (1969) wordless picture book, Frog, Where Are You? (book task) while another using a static picture (picture task) with visually rich

pictures of a traditional Mexican American family birthday party. The children were asked to tell four stories (i.e., two tasks in two languages). Children’s stories of both languages were scored for complexity of story grammar and the inclusion of specific narrative elements. The results showed that children produced narratives of equal complexity for the book task in each language. Nonetheless, children tended to produce more attempts and initiating events in Spanish while more consequences

in English. This study indicated that bilingual children had different performance on story grammar production in each of the language.

Berman and Slobin (1994) also used the wordless picture book as a narrative stimulus in their study. The results indicated that, in narratives of English, Turkish, German, Spanish, and Hebrew, there were linguistic and rhetorical differences appearing in tense, aspect, locative movement, connectively, and rhetorical style. The study revealed that various linguistic performance exists among children’s narratives in different languages. Other studies (Gutierrez-Clellen, 1998;

Guiterrez-Clellen & Heinrichs-Ramos, 1993; Gutierrez-Clellen & Iglesias, 1992) further provided a framework for comparing narrative development of monolingual and bilingual Latino-American children and specifically examined important grammatical markers and measures of narrative skills. For instance,

Gutierrez-Clellen’s study (2002) used the story recall and story comprehension tasks to examine the narrative performance of typically developing bilingual children. Thirty-three Spanish-English speaking children were randomly selected from second grade bilingual classrooms. The results showed that children’

performed differently in either narrative recall or story comprehension task, and the study was able to support the prediction that “typically-developing children who are fluent in two languages may not show equivalent levels of narrative proficiency in L1 and L2” (p.192). In conclusion, the study suggested that developing bilingual children were able to show age-appropriate performance in at least one language. In contrast, bilingual children with language disorders exhibited deficits in both languages.

Several studies compared bilingual children’s narrative productions in their two languages. Dart (1992) examined the narrative development of one bilingual

child speaking both French and English. He found that there were stylistic

divergences on modifiers and contrasting verb tenses. Silliman, Huntley Bahr, Brea, Hnath-Chisolm, & Mahecha (2002) compared nine-to eleven-year-old bilingual children speaking both Spanish and English, and they focused on children’s linguistic encoding of mental states in the narrative retellings.

There has been a growing number of studies on narrative development of bilingual children in many languages; however, little research has been done on bilingual children whose first language is Chinese. Therefore, research on Chinese bilingual children’s narrative development warrants more research attention.

Narrative Studies in Taiwan

Over the past decades, there have been an increasing number of studies on children’s narrative conducted in Taiwan. Many of them provide promising and interesting aspects warranting further attention. These studies also provide

important pedagogical implications for language teachers to consider incorporating storytelling into their language curriculum.

The first line of narrative studies focused on the narrative development from different aspects. For example,Chang (2004) explored the growth in Chinese children’s narrative development in Chinese over a nine-month period. Sixteen children living in Taipei, Taiwan were followed in this study. Children were visited in the home at ages 3; 6, 3; 9, and 4; 3, and were prompted to tell personally experienced narratives at each time. In this study, Chang assessed the individual growth of each child through three dimensions—narrative structure, evaluation, and temporality. The results showed that as children got older, they generally produced more narrative components, evaluative information, and temporal markers in their

narratives. Another study by Sung (2004) looked at children’s narratives at the microlevel. Taiwanese EFL children’s referential strategies in their Chinese and English narratives were examined and comparied. There were 30 six-grade

elementary children participated. The students were asked to produce a narrative in Chinese and English respectively using a picture book. The results revealed that those children performed well in adopting Chinese and English referential strategies in making references, but tended to make different performance of indefinite nominals, zero anaphors, and bare nominals in Chinese and English.

In addition to narrative development studies, researchers in Taiwan have also found that children’s narrative development has a relationship with their later literacy performance and academic achievement. Qi (2001) conducted a study to compare the performance of narrative coherence of 61 low-reading-proficiency with 63 general-reading-proficiency students. She indicated that children with low reading proficiency, comparing to those with general ones, tended to have

difficulties in controlling story cohesion, such as lack of order, coherence and organization. According to Qi’s (2001) study, examination on Taiwanese children’s narrative coherence could also provide pathological consideration on children’s future academic performance.

Another study by Zou and Cheung (2007) examined the language performance of Taiwanese autistic children by analyzing the content of their stories. This study assessed 19 autistic children and 19 typically-developing children from a preschool educational organization in Taipei, Taiwan. The two groups of children were about the same age (i.e., 5 years olds). Mayer’s frog story (1969) was used to elicit children’s story retelling without adult’s support. The results showed that children with autism presented significant differences from the control group on the

comprehension and expression of the story content. Children with autism showed the features such as performing weaker ability to express the character’s internal responses and goals, easily omitting the ending of the story, and mentioning more irrelevant details. In addition, they also lacked of the ability to express character’s emotion. Thus, it is apparent that children with autism might present different narrative comprehension and production abilities from typically-developing children.

Another line of studies looked at the role of storytelling in language teaching and learning. For example, Shu (2007) conducted a study to investigate the influence of picture books on Taiwanese fourth-graders’ academic performance and their

learning attitude. The stories were read aloud to 61elementary children to examine the effects. The results showed that reading the picture storybook aloud had a positive influence on children’s performance, including word recognition, reading comprehension, and children’s attitude. More studies also confirmed the effects of picture books on teaching and believed that it can help enhance children’s language achievement as well as learning attitude (Lin, 2004; Wu, 2005).

Other researchers also paid special attention to the effects of applying story grammar instruction on language learning (Cheng, 2006; Hung, 2007; Liu, 2007). Cheng’s study (2006), which aimed to examine whether story grammar instruction could enhance third-graders’ reading comprehension. The results revealed that story grammar instruction improved children’s story comprehension and reasoning ability, especially for children with low or intermediate language proficiency. In another study, Liu (2007) used story structure teaching to determine whether it would enhance young children’s learning. The study showed that through story structure teaching, children’s reading comprehension and their perception of story structure

were enhanced; in addition, children also had better abilities to utilize story elements in paraphrasing a story. According to the aforementioned studies, it was clear that story grammar teaching could be beneficial to children’s reading comprehension and understanding.

Story Grammar Analysis and Pertinent Studies

In the present study, story grammar will be used to analyze children’s narratives. The main definitions and categories of story grammar will be described.

There are various definitions for story grammar. It has been indicated that story grammar manifests the natural components of a story, the interrelationships, and also the roles in the global story macrostructure (Hedberg & Westby, 1993). Story tellers develop a schema for a story structure and use the schema to comprehend and produce stories. Mandler (1983) also pointed out that children develop a representation of a story by reading or hearing stories with common underlying structures. In addition, Bamberg (1987) mentioned that story grammar could be referred to as the story structures or a specific set of rules about what makes up a story.

Numerous story grammar models have been developed. First of all, Labov (1972) gave a description of narrative structures. He suggested that a well-formed personal narrative should consist of six components: abstract, orientation, action, evaluation, resolution, and coda. Abstract is used to serve as a short summary of the story, such as what the story is talking about; orientation aims to identify the setting and characters in the story, like the information of whom, when, what, or where about the story; complication is to manifest the details of events or actions in sequence, like what had happened in the story; evaluation reveals speaker’s comments or

viewpoints for the story; resolution is to provide the result or ending of the action in the story, and as for coda, which is the signal the overall completion of the story. According to Labov, evaluation is the most important element in a narrative, and it could also reveal narrator’s attitude towards the story. In other words, evaluation could show the significance of the story as well as manifest the evaluative functions of a narrative.

Nakamura’s study (1999) used Labov’s study to analyze Japanese children’s narratives, especially focused on the evaluative devices the participants used. The study was conducted with two goals: first, to examine the types of evaluative devices Japanese children and adults used to construct their oral narratives; second, to manifest the performance in using the evaluative devices across different ages. Children in this study were divided into four age groups: four, five, seven, and nine year olds, and the Mayer’s (1969) frog story book was used to collect children’s language samples. The results showed not much difference in number of evaluative usages across ages; however, nine-year-old groups tended to use the fewest

evaluative devices. The result differed from Bamberg and Damrad-Frye’s study (1991), which focused on English-speaking children’s narratives, pointing that adults used more evaluative devices than 5-year-old and 9-year-old children did.

Labov’s framework of narrative structure has been extensively drawn on in narrative studies of Indo-European languages. For example, Ulla (1996) compared monolingual and bilingual children’s narrative structures using the narrative structure rules generated by Labov (1972). In this study, 19 monolingual Swedish-speaking children (control group) and 19 Finnish-speaking immersion students with Swedish as their first language participated. The study analyzed the development of the second language of immersion students and also compared their

second language development to the control group. The frog story was also used as the elicitation material. Results showed that the immersion students presented almost as many plot components and subcomponents in an episode as the control group students did. Moreover, adequate linguistic expressions were also used to describe the initiative aspects of the story told by the immersion students. As for the performance of wrapping up the story, the immersion students and the control group showed no differences in indicating anaphoric reference.

In addition to Ulla’s research, which used Labov’s narrative structure to analyze monolingual and bilingual children’s narrative development, another study also adopted this model to examine the narrative production of Chinese-speaking children with reading disability. Lu’s study (2003) discovered the relation between oral language performance and literacy, from the perspective of idea packing. She made a comparison between children of learning disability (LD) and normal

children (control group). Twenty-one first- and second-graders with ages from 6; 10 to 7; 11 participated in the study. The tasks administered were made up of two narrative tasks: look-and-say task and retelling task. Children’s stories were

examined using narrative structure analysis and grammatical analysis. The narrative structure analysis showed that LD children did not perform as well as the control children did, especially in orientation, complication actions, resolution, and evaluation categories. As for the grammatical analysis, the LD children showed limited performance on some grammatical usages, including nouns, classifiers, or causal connectives. According to the study, it is concluded that there was a

correlation between Chinese-speaking LD children‘s oral language performance and their literacy proficiency. The study further pointed out that Labov’s narrative structure (1972) could be used to analyze the narrative structure of children with or

without reading disabilities.

In line with the narrative structures generated by Labov (1972), the story grammar model proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979) has been used most frequently to analyze children’s narratives. Compared to Labov’s narrative structure (1972) which has been developed for analyzing the functional components, the story grammar proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979) provides a more complete framework for analyzing the interrelationships between eposodes. This model shows

macrostructure components of a story as well as the semantic interrelationships among the elements. According to Stein and Glenn (1979), a story may consist of one or more related episodes; episodes may be linked additively, temporally, causally, or contractively. A model episode contains some or all of the components, which include setting, initiating event, reactions and attempts, consequence,

reaction or resolution, and ending.

Numerous studies have used the components defined by Stein and Glenn (1979) to analyze the story structure in their research (Applebee, 1978; Gillam, McFadden, & van Kleeck, 1995; Hughes, McGillivray, & Schmidek, 1997; Stein & Glenn, 1979; Westby, 1984). For example, Merritt and Liles (1979) used Stein and Gleen’s (1979) story grammar ruleto analyze children narratives. In their study, 20 children with language impairment and normal language (control group) aged raging from 9; 0 to 11; 4 were examined. Both groups of children were asked to generate and retell stories. The results indicated that language-impaired children, compared to the control group, tended to produce stories with fewer complete story episodes, lower mean number of main and subordinate clauses, and also lower frequency of using story grammar components. Moreover, the study further indicated that the two groups did not perform differently in understanding the

factual details but did show different performance in comprehension of the relationships between the episodes that link the stories together.

Analyzing children’s narratives using story grammar analysis has been an established method to describe and identify language development and disorders among monolingual children (Gillam, McFadden, & van Kleeck, 1995; Merritt & Liles, 1987; Roth & Spekman, 1986). It is noted that children’s narratives can be used as an important tool to examine children with language disorders; therefore, a study was conducted to compare story retellings of learning-disabled (LD) and nondisabled children (ND) and across different age groups (Griffith, Ripich, & Dastoli, 1986). The outcome measures of the study were the story event correctly recalled, story structures, propositions, and cohesive devices produced by both groups of children. Twenty-four LD children and 27 ND children participated and were asked to retell three stories read to them, which were labeled easy, medium, and hard on the basis of number of events. The results indicated that LD children performed as well as ND children did both on the amount of information they recalled and on the story organization according to the story grammar. However, all children were capable of accurately recalling the initialing events and the

consequences while LD children had great difficulty in recalling the internal response and the internal plan. With respect to the developmental differences, older children in both LD and ND groups recalled more events than the younger children did. In addition, they tended to produce more inaccurate statements in longer stories. This study suggested that children with different learning abilities and different ages performed variously in story telling and story grammar.

Only scarce information on the development of story structure among non-English-speaking children is available. Hang’s study (2006) focused on the

production of goals and plans in narratives of Cantonese-speaking children. The study firstly provided the introduction to the categories and division to various approaches to narrative analysis. The study indicated that different approaches focused on different aspects of narrative productions (Berman, 1995), including content, structure, and relationship between form and function of narratives respectively. In addition, two streams of methods in studying the content of narratives were introduced in this study: story grammar components (Stein & Glenn, 1979) and goal-plans (Berman, 1995). The goal-plan analysis could be considered as a variation of story grammar. Therefore, in Hang’s study (2006), the development of goal-plan components in normally developing children was analyzed. A total of 100 kindergarten and primary school children whose primary language was Cantonese participated in this study. There were from different age groups: 3; 0, 4; 0, and 5; 0. The goal-plan components investigated in this study were setting, initiating events, attempts, and outcomes. The results showed that children acquired different goal-plan components at different ages: setting at the age of seven, attempt at the age of nine, and outcome at age five.

Within the extensive literature on children’s narrative development, literature on narrative development of EFL children with Chinese as their native language has emerged in a relatively slow and limited way. Although there were some bilingual or cross-language narrative studies, most of them focused on the microlevel (e.g., cohesion) of children’s narrative. Therefore, the present work aims to examine development of the narrative structure of EFL children in Taiwan.

The purpose of this study was to examine the narrative development of Taiwanese EFL children, using the analyses of story grammar proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979).First, in order to see the developmental trajectory of narrative

development, narratives produced by two age groups—school-aged and preschool children-- were compared. Second, both Chinese and English narratives were also examined to further understand the differences between the two languages.

CHAPTER THREE METHOD

The Study

The purpose of this study was to examine the narrative development of

Chinese-English speaking children in Taiwan. Children’s stories was obtained from the narrative language samples using the wordless picture book, Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969). All children’s stories were analyzed according to Stein and Glenn’s (1979) story grammar. Background of participants, materials, data collection procedures, transcription and coding procedures will be presented in the following sections.

Participants

The participants of this study were 44 EFL children (16 boys and 28 girls). Two groups of children were recruited to participate in the present study: 21 of them were from an English-immersion kindergarten and with a mean age of five years and 11 months (range = 4; 10 - 6; 10), while the other 23 were from an afterschool program with a mean age of nine years and two months (range = 7; 11- 10; 00). A large percentage of their parents received college education or higher degrees (preschool children’s paternal education: 82%, maternal education: 82%; school-aged children’s paternal education: 83%, maternal education: 79%). A certain percentage of their parents worked as high-level or senior administrators (preschool children’s paternal occupation: 59%, maternal occupation: 36%; school-aged children’s paternal occupation: 58%; maternal occupation: 43%).

located in Tainan, Taiwan and belonged to the same educational organization. All children were native speakers of Mandarin Chinese and learning English at preschool ages. Both groups of children exhibited typical language development and had no reported problems with their learning.

English-immersion Kindergarten

Twenty-two children from an English-immersion kindergarten were from K4 and K6 classes (i.e., the fourth and sixth semester in a three-year kindergarten). The kindergarten was an English immersion program where English was the primary medium of instruction. In this immersion program, each class had one classroom teacher who was a native speaker of English from English-speaking country (e.g., the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the U.K., or South Africa etc.). The class size was about 10-15 students. Chinese-speaking teachers were the assistants for each of the classroom, but they were not involved in teaching the curriculum. They were responsible for assisting English teachers with classroom management and

communicating with students’ parents. During lunch hours and naptime, they also provided necessary care of children.

A typical day at the English-immersion kindergarten started with aerobics at 8:30 a.m. with MPM (Multi-Process-Model) math, computer, lunch hours, and nap time followed. The afternoon lessons included music, movement, arts, and English reading and writing. The school day ended at 5 p.m. This English-immersion program was locally renowned and was charged with high fee. Therefore, the children recruited were mostly form middle- or upper-middle-class families.

After School Program

After-school program included six levels corresponding to the six grades in elementary schools. It provided elementary-school students with English training after they finished school lessons. Most students in this program came to this program twice a week and some of them came every week day. Every class lesson was instructed by a native English-speaking teacher and class sessions lasted two hours every day. Three Chinese-speaking teachers were responsible for the primary-level (e.g., first and second grader of elementary school), middle-level (e.g., third and fourth grader) and high-level (e.g., fifth and sixth graders) students respectively.

Materials

The wordless picture book, Frog, Where Are You? (Mayer, 1969) was used in this study. It was chosen because it standardizes the content of expressions with

extensively analyzed structure (Bamberg, 1987; Merman & Slobin, 1994), which was easy for children to comprehend and to describe. The story includes different goal and plan elements as well as a complete structure for doing the research of story grammar. In addition, the book is not commonly available, and thus the participants would not have prior exposure to this book. The wordless feature of this picture book allows children not to be constrained by the writer’s intended storyline. Given these special characteristics of this picture book, it has been adopted as a worldwide research tool to examine children’s narratives.

The book included 24 pictures without literate instructions and it has been widely used in narrative research. The story illustrates the adventures of a boy and a dog during their search for a lost frog. The two main characters go through a series of troubles during the process.At the beginning of the story, the picture shows a boy and

a dog looking at a frog inside a jar. In scene two, the boy and the dog fall asleep and the frog leaves the jar. Scene 3 shows that they find the jar empty and realize that their frog is gone. The initiating events shown in scene two and three cause the boy and the dog develop a goal to search for the frog. In the following scenes, the boy starts a series of attempts to find the frog back. Several plots sequentially happened, including looking for the frog inside the room, at the window, and outside in the forest. As they find the frog in the forest, they encounter several troubles as well. All attempts end in failure, and each of the failures leads to another attempt. The boy and the dog finally find the frog in scene 22 behind a log near a lake. Besides the frog, other frogs are also founded. As a result, the boy finishes his attempts and successfully takes the frog back.

Data Collection and Procedures

The data were collected during the summer of 2008. The procedure of data collection lasted for six weeks. The researcher spent first two weeks staying in the classroom and did the class observation. Before the narration task, school and parental permission (See Appendix A) were obtained and parents completed a brief

demographic questionnaire (See Appendix B and C). During the data collection process, the participants were invited individually into a quiet classroom. Each participant was first presented with Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (TONI) test

(Brown, Sherbenou, & Johnsen, 1990), which is a language-free measure of cognitive ability. The TONI test was conducted to ensure the participants had comparable and typical cognitive functioning according to their age norm. Each participant was presented with the wordless picture book and began with looking through it. After they finished looking through the book, each child was given all time they needed to

plan and tell the story. The participants were asked to tell the story in Chinese and English respectively without the adult’s support at two different times in separate occasions. Finally, parental socioeconomic information was collected as well (See Appendix D).

The participants’ storytelling was initiated by the researcher’s saying, “Can you tell me what is happening in this book?” During the story-telling process, the

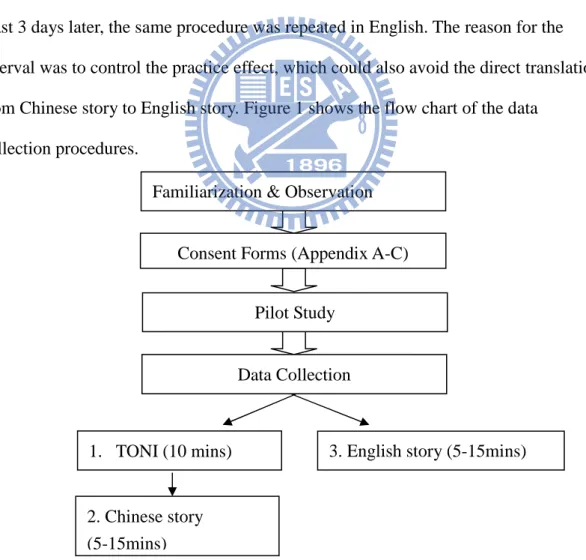

researcher only gave general, neutral subprompts such as “uh-huh,” “Tell me more,” “Then what happened?” or to restate the participants’ last utterance in response to the child’s answers to avoid adult’s interference. Children first told the stories in Chinese, their supposedly stronger language, so as to increase familiarity with the tasks. At least 3 days later, the same procedure was repeated in English. The reason for the interval was to control the practice effect, which could also avoid the direct translation from Chinese story to English story. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the data

collection procedures.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the data collection procedures.

Familiarization & Observation

Consent Forms (Appendix A-C)

Pilot Study

Data Collection

1. TONI (10 mins)

2. Chinese story (5-15mins)

The whole process of performing the task was digitally-recorded, and the transcription of children’s stories in Chinese and English followed conventions from the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (See Appendix E) or SALT software (Miller et al., 2006).

Transcription Procedures

All Chinese and English narratives were first transcribed by two trained graduated students. After transcription, modified communication unit (C-unit) was used to segment the narratives. Next, the story grammar model proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979) was adopted to analyze each story.

The digital sound files of children’s narrative samples were transcribed and analyzed in verbatim. Two trained Chinese-English speaking graduate students in the Institute of TESOL of National Chiao-Tung University independently transcribed the Chinese and English oral narratives into computer text files, following transcription conventions of the SALT (Miller et al., 2006).

Next, Communication Unit (C-unit) (Loban, 1976) was used to define utterance segmentation.In this study, two sets of language data—Chinese and English were segmented following the same rules. A C-unit is defined as the independent clause with its modifier, which includes no more than one independent clause and any other related dependent clauses. However, there were difficulties using Loban’s C-unit definition (1976) to segment children’s Chinese stories. Therefore, the “modified C-unit” was further defined. Take English language for example, the main clauses were segmented with the conjoined simple coordinate conjunctions (e.g., and, but). For example, in English sentences:

The above sentence was segmented into two C-units according to the rules of segmenting with conjoined simple coordinate conjunction “and.” While in Chinese samples, sentences like the following were segmented into two C-units as well:

“Ta ting dao qing wa di sheng yin, /ran hou ta jiu jiao He heard frog ‘s sound then he shout 他 聽到 青蛙 的 聲音 , 然後 他 就 叫

gou gou an jing.” dog quite 狗狗 安靜

He heard the frog’s sound, and then he wanted the dog to be quite.

As shown in the above, the sentence was segmented into two C-units because of the coordinate conjunction “then.”

An initial transcription for both Chinese and English samples was completed by the author, which was then reviewed and examined by the other graduate student transcribers. Once transcribed and mutually examined, narratives were coded for story grammar.

Transcription Reliability

In order to ensure the transcription reliability, 20 % of all stories was randomly selected for inter-rater reliability and independently transcribed by another trained graduate student. Both Chinese and English stories achieved reliability above 90% (Chinese: 93%; English: 92%).

Data Analyses

After children’s narratives were segmented into C-units, they were further analyzed using the story grammar components. After that, all of children’s stories were categorized into different story grammar levels suggested by Westby et al. (1984; 1986). In addition, the descriptive analyses of children’s stories were also illustrated.

Story Grammar Analyses

To examine children’s development of story structure, story grammar (Stein & Glenn, 1979) was used for the method of analysis.Story grammar specifies the natural components of a story, the interrelationships as well as the roles of each component in the global story macrostructure. People develop schemes for story structure and use the schemes to comprehend and produce stories (Stein & Trabasso, 1982). Different story grammar models have been developed by other researchers (Colby & Prince, 1973; Halliday & Hasan, 1976). The one proposed by Stein and Glenn (1979) has been the most frequently used one in analyzing children’s narrative productions. According to Stein and Glenn (1979), a story consists of one or more episodes, and a model episode contains some or all of the components including (1) setting, (2)

initiating event, (3) reactions and attempts, (4) consequence, (5) reaction or resolution, and (6) ending.The description and example of each story component are presented in Table 1.

Table 1

Story Structure Components

_____________________________________________________________________

Component Description

1. Setting (S) Where and when the story takes place; the character(s); and the social, physical, or temporal contexts in which the story occurs.

Example: It was a dark night, and a child is called Tom. ____________________________________________________________________ 2. Initiating Event

(IE)

The situation or problem to which a character must respond.

Example: When Tom was sleeping, the frog ran away.

_____________________________________________________________________ 2. Reaction

(Internal Response = IR):

Internal State (IS) The psychological state (feeling, desired goal) of the character after the initiating event.

Example: Tom was very nervous. Internal Plan (IP) A character’s strategy for attaining a goal

Example: He searched everywhere in his room.

Behavior/ Action (B) A non-goal-directed behavior or action in response to the initiating event

Example: They looked out through the window (IP),/ but the bottle fell down and broke (B).

_____________________________________________________________________ 4. Attempt (A) What the character does to reach the goal

Example: They went outside and shouted out: frog, where are you?

5. Consequence (C) The character’s success of failure in achieving a goal Example: The boy looked for the tree (IE),/

but a group of bees ran after him (C).

6. Resolution/ Reaction (R)

The character’s feelings, thought, or actions in response to the consequence of attaining or not attaining the goal.