Modeling Corporate Citizenship

and Its Relationship with Organizational

Citizenship Behaviors

Chieh-Peng Lin

Nyan-Myau Lyau

Yuan-Hui Tsai

Wen-Yung Chen

Chou-Kang Chiu

ABSTRACT. Citizenship, such as corporate citizenship and organizational citizenship, has been an important is-sue in business management for decades. This study proposes a research model from the perspectives of social identity and resource allocation, by examining the influ-ence of corporate citizenship on organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs). In the model, OCBs are positively influenced by perceived legal citizenship and perceived ethical citizenship, while negatively influenced by per-ceived discretionary citizenship. Empirical testing using a survey of personnel from 18 large firms confirms most of our hypothesized effects. Theoretical and managerial implications of our findings are discussed.

KEY WORDS: corporate social responsibility, organi-zational citizenship behavior, ethical citizenship, discre-tionary citizenship

Introduction

The global village has increasingly welcomed cor-porate citizenship as a set of business practices desir-able not only for society in general, but also for business organizations (Maignan and Ferrell, 2000). Corporate citizenship – also known as corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate responsibility, or responsible business – is a form of corporate self-regulation integrated into a business model (Grit,

2004; Kell, 2005; Lam, 2009; Maxfield, 2008; Okoye, 2009; Torres-Baumgarten and Yucetepe,

2009; Wood,1991). Corporate citizenship is defined as a company’s engagement in activity that appears to advance a social agenda beyond that required by law (Siegel and Vitaliano,2007). Corporate citizenship is

developing rapidly across a variety of popular initia-tives, such as the financing of employees’ education, promoting ethics training programs, adopting envi-ronment-friendly policies, and sponsoring commu-nity events (Maignan and Ferrell, 2000). For example, a bank is considered to present corporate citizenship when it frequently approves loans to minority borrowers than required by the government regulations. Similarly, car manufacturers producing ‘‘hybrid’’ vehicles beyond the government require-ments of fuel efficiency are considered good corpo-rate citizenship behavior (Siegel and Vitaliano,2007). Recent theories of corporate citizenship assert that firms with good corporate citizenship are con-ducting ‘‘profit-maximizing’’ business (Bagnoli and Watts, 2003) – that is, the emergence of corporate citizenship as a well-recognized managerial practice is closely associated with the growing belief that an organization performing corporate citizenship is a good one in terms of stakeholders like consumers, investors, employees, and so on. Siegel and Vitaliano (2007) emphasized about how the activity of cor-porate citizenship should be integrated into a firm’s differentiation strategies to make sales profits. It is even asserted that firms compete for socially responsible customers by explicitly linking their social contribution to product sales (Baron, 2001). Examples of benefits from corporate citizenship for a firm may include the ability to charge a premium price for its product, to have a good business image, or to attract investment.

Margolis and Walsh (2003) shows that 53% of the identified studies report evidence of a positive rela-tionship between corporate citizenship and financial DOI 10.1007/s10551-010-0364-x

performance (with 5% of the evidence of a negative relationship), whereas 24% report an insignificant relationship and 18% report inconclusive evidence (Kristoffersen et al., 2009; Margolis and Walsh,

2003). Nevertheless, Margolis and Walsh (2003) go as far as arguing that further research in this area is futile because some underlying theoretical frame-work and research methods employed are flawed (Kristoffersen et al., 2009; Margolis and Walsh,

2003). Meanwhile, prior meta-analysis reflects a growing body of research supporting that corporate citizenship has a positive influence on both corpo-rate financial performance (e.g., He et al., 2007; Orlitzky et al., 2003; O’Shaughnessy et al., 2007) and the sustainability of above average profitability (Orlitzky et al.,2003; Roberts and Dowling,2002). Compared to corporate citizenship, individual cit-izenship in the organization – in which his or her behavior is regarded as organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs) – is also considered important for the organization’s sustainability. Note that OCBs are a unique aspect of individual activity at work in nature. Originally defined by Organ (1988), OCBs represent ‘‘individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and in the aggregate promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the organiza-tion’’ (Organ, 1988, p. 4). Research suggests that OCBs are consistently related to organizational effectiveness (Podsakoff and MacKenzie, 1997), while other research has categorized individuals’ behaviors in an organization to two dimensions: in-role behaviors and extra-in-role behaviors. In-in-role behaviors involve with those who do the least pos-sible to maintain membership while extra-role behaviors involve those who go beyond general expectations to promote the effective operation of the organization or to benefit others in the organi-zation. Such extra-role behaviors are considered OCBs. Examples of OCBs by employees include cooperating with others, orienting new staffs, vol-unteering for extra works, and helping others in their job.

Previous studies have initially proposed two pri-mary dimensions of citizenship behaviors: consci-entiousness and altruism (Organ, 1988). Later research added sportsmanship, courtesy, and civic virtue to citizenship behaviors (Organ, 1988). Altruism is characterized as a helping behavior that

comprises all discretionary behaviors that help a specific person in performing an organizationally relevant task (Organ, 1988). Courtesy encompasses behaviors such as being mindful of how one’s behavior affects others and attempting to avoid creating problems for co-workers. Conscientious-ness is discretionary behavior beyond the minimum role requirements expected by an organization (Organ, 1988). Sportsmanship encompasses behav-iors that focus on what is right rather than wrong in an organization. Finally, civic virtue is constructively involved in an organization’s processes, going beyond the minimum required by an individual’s immediate job (Organ, 1988). Collectively, being a matter of personal choice, OCBs are a special type of work behavior that are beneficial to the organization and are discretionary, not explicitly or directly recognized by the formal reward system of the organization.

Corporate citizenship is not a plea for business organizations to take on the burden of the whole world (Jeurissen, 2004). Corporate citizenship is socially distributed across the organizations that profess to be citizens and assume their share of the responsibility to advance a social agenda beyond that required by law. Yet, the question remains how realistic the corporate citizenship is beneficial to their employees’ citizenship inside the organization (e.g., OCBs). Much research has examined the antecedents of either corporate citizenship or OCB. However, little research has explored the relation-ship between the corporate citizenrelation-ship perceived by individual employees and the OCB performed by the employees, let alone to discuss whether the perceived corporate citizenship is always good for boosting their OCBs. As an old saying goes, example is better than precept. It is very likely that the good examples of corporate citizenship set up by an organization will result in a positive influence on individuals’ citizenship behavior toward the organi-zation (i.e., OCBs). Although a majority of research has explored numerous determinants of OCBs from three major aspects such as individuals’ (e.g., per-sonality), their job’s (job satisfaction), or interorga-nizational characteristics (e.g., perceived fairness, leader supportiveness), there lacks a thorough understanding about how OCBs may be driven positively or negatively by perceived corporate cit-izenship which is somewhat externally beyond the

above three aspects. Based on the research gap above, two research questions are examined in this study.

RQ1: What dimensions of perceived corporate citizenship have significant effects on OCBs?

RQ2: What direction of the above effects (positive, negative, or both) is it?

This study differs from previous research in three critical ways. First, while previous studies linking corporate ethical values to OCBs did not examine various dimensions of the perceived corporate citi-zenship in depth (e.g., Baker et al., 2006), by eval-uating perceived corporate citizenship from various different dimensions relevant to organizational members this study can effectively generate further understanding about the influence of different per-ceived corporate citizenship on OCBs, which is important as some researchers studying corporate citizenship have failed to take its multi-dimensional nature into account (De los Salmones et al., 2005). Second, given that different stakeholders react to corporate citizenship differently, this study focuses on employees’ reactions to corporate citizenship, which is quite different from a majority of previous studies emphasizing consumers’ or investors’ reac-tions to corporate citizenship (Maignan and Ferrell,

2004). Indeed, previous research indicates the importance of knowing who are the stakeholders and what they expect before an organization gages the effectiveness of corporate citizenship (Murray and Vogel, 1997). Third, this study is a pioneer to examine both the positive and negative sides of corporate citizenship in the formation of OCBs. Although a majority of research has encouraged management to practice corporate citizenship from a positive point of view, little of the previous research has considered a potential negative point of view in the formation of OCBs. While some organizations endeavor to practice corporate citizenship (e.g., O’Shaughnessy et al.,2007), the reluctance of many other organizations in, for example, developing countries (Van Staden,2009) to develop an explicit corporate citizenship program suggests that the activities of corporate citizenship sometimes repre-sent, for example, a cost-intensive or problem-fraught effort with no obvious payoff for the organizations (Murray and Vogel,1997). For example, collectively,

by evaluating both positive and negative sides of corporate citizenship in influencing OCBs, a clear picture of how corporate citizenship actually influ-ences OCBs can be well developed.

Development of theory and hypotheses Being a high-profile notion that has strategic sig-nificance to business firms, corporate citizenship represents a firm’s activities and status related to its perceived societal and stakeholder obligations (Luo and Bhattacharya,2006). Corporate citizenship often occurs when a firm engages in activities that advance a social agenda beyond that merely required by law (Siegel and Vitaliano, 2007). Some researchers have studied the degree to which corporate citizenship is applied in firms (Joyner and Payne, 2002), while others have tried to measure the relation between social performance (i.e., corporate citizenship) and employer attractiveness (Backhaus et al., 2002). Nevertheless, none of studies have tried to clarify how perceived corporate citizenship influence employees’ OCBs, which this study examines.

In evaluating whether the corporate citizenship perceived by individuals is truly good for encour-aging their OCBs, there are two issues to take into consideration: social identity and resource allocation. First, social identity theory is a diffuse but interre-lated group of social psychological theories con-cerned with when and why individuals identify with, and behave as part of, social groups (or orga-nizations), adopting shared affection and attitudes inside the groups (or organizations). Based on social identity theory, corporate citizenship may be expected to contribute positively to the affection, attribution, retention, and motivation of employees, because they often strongly identify with positive organizational values (Peterson, 2004). Second, when it comes to resource allocation, corporate citizenship may not be necessarily good for strengthening OCBs – that is, if the activities of corporate citizenship not directly related to business operations are perceived by employees as competing on resources (e.g., a large donation), then the employees’ OCBs may be discouraged. For example, some CEO would make charity donation with a huge amount of money to win good reputation in public rather than make improvement for

employees’ welfare. Such money, considered a critical resource, for either making the charity donation or the welfare improvement comes from the same organization. The concept of resources is described as a pool of capital units coming from a common source, from which resources are drawn and allocated to different areas (Bergeron, 2007). Implied in the resource capacity is the notion of scarcity, the limited capacity assumption, which means that multiple demands (e.g., business opera-tions versus charity donaopera-tions) must compete for the same units of the capital within the pool of resources (e.g., Hockey,1997).

Corporate citizenship is valuable to OCBs in terms of social identity theory, because the percep-tions of an organization’s identity – the beliefs held by its employees regarding its central, enduring, and legitimate attributes (e.g., legal activities) – largely affect the strength of the employees’ identification and their subsequent citizenship behavior inside the organization (Dutton et al.,1994). Indeed, previous research suggests that organizational identification contributes to an individual’s self-concept, and an individual’s positive and negative cognitive rela-tionships with a work organization provides the important basis for social identity (Berger et al.,

2006; Elsbach, 1999), substantially affecting job sat-isfaction, organizational commitment, and desirable work-related behaviors (e.g., Brown et al., 2006) such as intraorganizational cooperation (e.g., Berger et al.,2006), lower turnover and OCBs. Particularly, business organizations can leverage marketing-driven social alliances to positively give employees more complete senses of identity, and increase positive organizational identification (Berger et al.,

2006). However, studies to date have generally focused on positive effects of corporate citizenship on various outcomes, yet what has not been addressed well in previous research is the negative effects of some particular corporate citizenship, which may exist in impacting OCBs negatively. In addition to social identity theory, this study applies a resource allocation concept (e.g., Freedman and Montanari,

1980) to individuals’ benefits which can help us gain an understanding for why and how perceived cor-porate citizenship may be detrimental to OCBs.

Dutton et al. (1994) indicate that the better rep-utation employees made with their organization, the more they identity with it, eventually affecting their

organizational behavior (e.g., OCBs). In fact, repu-tation often comes into play in social identity theory (e.g., Dutton et al.,1994; Emler and Hopkins,1990; Whetten and Mackey, 2002). Previous literature indicates that the social performance (e.g., corporate citizenship) is strongly associated with how organi-zations are perceived by both their employees (i.e., their identities) and their external constituents (i.e., their reputations) (Berger et al.,2006; Dutton et al.,

1994). An organization often quests for its intended reputation (or image) to be compatible with the organizational identity that its employees form (Brown et al., 2006).

Corporate citizenship in this study consists of four dimensions refined from previous literature from the perspective of employees in the organization: (1) economic citizenship, referring to the organizational obligation to bring utilitarian benefits to its employees and other stakeholders by providing job opportunities, payoff, and training, producing qual-ity goods (or services), and selling them at a profit (e.g., Zahra and LaTour,1987); (2) legal citizenship, referring to the organizational obligation to fulfill its business mission within the framework of legal requirements; (3) ethical citizenship, referring to the organizational obligation to abide by moral rules defining proper behavior in society; and (4) discre-tionary citizenship, referring to the organizational obligation to engage activities that are not mandated, not required by law, and not expected of business in an ethical sense (Maignan and Ferrell, 2000). Note that this study excludes economic citizenship and particularly focuses on another three kinds of perceived corporate citizenship (legal, ethical, and discretional citizenship) regarding their influence on OCBs, because economic citizenship is the basic and fundamental one in nature in our society (Carroll,

1979) and thus is unlikely to influence OCBs theoretically (i.e., neither literature support nor theoretical support). A typical example of firms’ economic corporate citizenship is the payroll they meet, which happens as a matter of course to employees and general public, suggesting the neutral (or indifferent) role of economic corporate citizen-ship in influencing OCBs across different firms. In-deed, previous research indicates that OCBs are employees’ behaviors that are beyond the call of duty and are discretionary and not financially rewarded in the context of an organization’s system (Turnipseed,

2009), supporting the insignificant influence of economic corporate citizenship (e.g., paycheck reward) in driving OCBs across various firms.

The first corporate citizenship that may influence OCBs is perceived legal citizenship of employees according to social identity. Society’s members ex-pect business to fulfill its mission within the frame-work of legal requirements (Carroll,1979), and thus employees’ OCBs can be well fostered under cir-cumstances of fulfilled legal citizenship by their organization. Just as society has sanctioned the eco-nomic system by allowing business to assume the productive role, as a partial fulfillment of the ‘‘social contract,’’ it has also laid down the ground rules, the regulations, and law, under which business is antic-ipated to operate (Carroll, 1979). A quality work-force with good OCBs is likely presented, because employees are often proud to identity with an organization that has a favorable reputation without it breaking the law (e.g., Peterson,2004).

Given that individuals attempt to establish or en-hance their self-concept for OCBs positively through a comparison of their own characteristics and the organization they belong to (Brammer et al., 2007; Johnson and Chang, 2006), social identity theory hypothesizes that individuals’ self-concept is en-hanced when they associate themselves with the organization that has a legitimate reputation, leading to the positive association between perceived legal citizenship and OCBs. Indeed, legal (or instrumental) citizenship designates the corporate duty to meet or exceed employees’ norms dictating desirable OCBs (Maignan and Ferrell, 2004). For example, when employees perceive that their manager or organiza-tion emits chemically polluted water without waste water treatment only to save the expenses (i.e., bad corporate citizenship), their individuals’ citizenship behavior (i.e., OCBs) become highly discouraged. Thus, the hypothesis is developed as below.

H1: Perceived legal citizenship is positively related to OCBs, including altruism (H1a), conscien-tiousness (H1b), sportsmanship (H1c), courtesy (H1d), and civic virtue (H1e).

Similar to the above hypothesis, perceived ethical citizenship has also a positive influence on OCBs based on social identity. Ethical corporate responsi-bilities of firms represent behaviors and activities that

are not necessarily codified into law, but nevertheless are anticipated of business by society’s members including the firms’ employees (Carroll, 1979). Employees’ perceptions about their firm’s ethics and social responsiveness play a significant role in shaping employees’ OCBs in the firm (Greening and Turban,

2000). When employees perceive that their firm conducts business over and above the legal require-ments on a layer of moral and ethics, they are likely to feel esteemed and highly identify with their firm by performing positive behaviors in the firm, leading to a positive relationship between perceived ethical citi-zenship and OCBs. Conversely, it is important to realize that even though an individual may uphold the highest moral standards and behavior, the unethical type of organization one works for can still exert a strong and negative impact on its members and thus predispose them to engage in deviant behavior (Appelbaum et al.,2007), negatively hurting OCBs. It is important to note that an organization being legal does not necessarily guarantee that it always behaves ethically (e.g., political scandals, gender, or racial discrimination could still exist in the organization) (e.g., Mescher,2008). Thus, it is essential to examine whether perceived ethical citizenship is positively related to OCBs after our preceding hypothesis related to perceived legal citizenship is proposed.

Based on the criticisms about corporate citizen-ship motivated by self-interest, some scholars advo-cate an ethics-driven view of corporate citizenship that asserts the rightness or wrongness of specific corporate activities independently of any social or stakeholder obligation (Maignan and Ferrell, 2004). This view is somewhat analogous to the spirit of OCBs which are not the obligation of any particular employee, such that their omission is not generally understood as punishable. Ethical responsibility ta-ken by firms refers to them being honest in their relationship with, for example, their own employees (De los Salmones et al., 2005), and thus the employees are likely to reciprocate with good behavior based on strong identity, consequently leading to good OCBs. As OCBs can be considered the manifestation of ethical behavior in the work-place (Turnipseed, 2002), employees who perceive their corporate citizenship to be good are likely to manifest their behavior to be a good citizen in the organization, suggesting a positive relationship between perceived ethical citizenship and OCBs.

A previous study by Baker et al. (2006) provides partial support for this perspective by confirming a significant influence of corporate ethical values on OCBs. Based on the above rationale, the hypothesis is provided as follows.

H2: Perceived ethical citizenship is positively re-lated to OCBs, including altruism (H2a), conscientiousness (H2b), sportsmanship (H2c), courtesy (H2d), and civic virtue (H2e). Discretionary corporate responsibilities are those about which society has no clear-cut message for business organizations and they are left to individual judgment and choice (Carroll, 1979). Thus, the ef-fect of discretionary citizenship on OCBs cannot be effectively explained herein by social identity theory. Examples of discretionary actions by business orga-nizations can be making philanthropic donations, sponsoring partnerships with non-profit organiza-tions, sponsoring local sports or cultural activities, dedicating environmental resources, or caring for social welfare. Although discretionary citizenship is welcome by the public, it may be somewhat dis-tasteful to the employees based on limited organi-zational resources. One of the common complaints of employees relates to their payoff, fringe benefits, compensation, or additional healthcare insurance, which take lots of resources to implement. In reality, business organizations all have limited resources to put in various business activities, such that it is not possible for the organization to actively perform discretionary citizenship (e.g., sponsorships and philanthropic contributions) without using existing limited resources in short-term operations. Prior work on corporate citizenship seldom takes into consideration that an organization is constrained by resources, one of which is money that directly generates the interests of either the stakeholders in-side the organization (i.e., employees) or the stake-holders outside the organization (e.g., charity institutions). There is a fixed amount of resources, and an organization must make choices as to how many resources to allocate to its business activities versus discretionary activities that are unrelated to immediate business interests or profits. For example, spending excessive money on latter activities nec-essarily comes at the expense of former activities. Indeed, previous literature indicates that using

corporate resources for social issues not related to primary stakeholders (e.g., a firm’s employees and consumers) may not create value for shareholders (Hillman and Keim,2001). The data from S&P 500 firms have been analyzed and found that social issue participation (e.g., arbitrary donations or discre-tionary sponsorship) is negatively associated with shareholder value or employees’ welfare (Hillman and Keim, 2001). Prior empirical research argues against broad social responsibilities such as donating money to a community institution if it is (as it often is) at the expense of interests of other stakeholders, such as employees, who might then receive lower pay, or consumers, who might then pay higher prices (Lantos, 2002). Of course, it is not exactly a zero–sum relationship between both kinds of activ-ities, but any substantial increased resources allocated to discretionary activities come at a cost to the de-creased resources allocated toward purely organiza-tional business activities in the short run, and vice versa (e.g., Bergeron, 2007).

It is even considered feasible in previous research to calculate the impact of corporate citizenship activities in terms of resources allocated to social programs (Murray and Vogel,1997). While perceived legal and ethical citizenship may positively motivate employ-ees’ OCBs, perceived discretionary citizenship may bring on certain threats of excessively using resources that could be used for enhancing the employees’ or the entire organization’s interests, weakening OCBs. In order to obtain outstanding corporate citizenship, organizations allocate some of their efforts and expenses to discretionary activities that do not directly generate profits for the organizations. Any limited amount of resources for every organization will decrease after some resources are spent on discre-tionary activities. Some employees may even feel their organizations to be hypocritical if the organization arbitrarily uses resources in, for example, philan-thropic donations without considering employees’ reception of the philanthropism or even force them to participate in particular charities, leading to a negative impact on employees’ OCBs. For example, after the earthquake in Sichuan Province, China, the CEO of Hasee Computer Co., Ltd asked his employees to quit their job if they did not want to make donations for the natural disaster. Based on the above rationale, the hypothesis is proposed as below.

H3: Perceived discretionary citizenship is nega-tively related to OCBs, including altruism (H3a), conscientiousness (H3b), sportsmanship (H3c), courtesy (H3d), and civic virtue (H3e).

Methods

Subjects and procedures

The research hypotheses described above are empir-ically tested using a survey of personnel from large firms within an industrial zone in central Taiwan. Of the 520 questionnaires distributed to the subjects, 421 usable questionnaires were collected for a re-sponse rate of 80.96%. A satisfactory rere-sponse rate of our survey is mainly due to two major reasons. First, we have the strong support of our sample firms in which their personnel departments helped distribute the questionnaires to employees expressing their voluntariness and then traced the status of returned questionnaires. Second, we promised to provide our findings for samples firms, which also interests most of their managers. To sum up, it turned out that we successfully collected all our data in a month. TableI

shows the characteristics of the sample.

Measures

The constructs in this study are measured using 5-point Likert scales drawn and modified from existing literature. A few steps are employed in choosing measurement items. First of all, the items from the existing literature are translated into Chi-nese from English and then the items in ChiChi-nese were substantially modified by a focus group of four people familiar with CSR, including three graduate students and one professor. In addition, following the questionnaire design, this study conducted two pilot tests (prior to the actual survey) to assess the quality of our measures and improve item readability and further clarity if needed. Last but not least, tips of back-translation indicated by Reynolds et al. (1993) were applied in comparing an English version questionnaire to a Chinese one. A high degree of consistency between the two questionnaires assures

that the translation process of this study did not introduce serious translation biases in the Chinese version questionnaire. TABLE I Sample characteristics Characteristic n = 421 Gender Male 312 (74.11%) Female 109 (25.89%) Age 20–29 years old 84 (19.95%) 30–39 years old 271 (64.37%) 40–49 years old 58 (13.78%) 50–59 years old 7 (1.66%) 60 or above 1 (0.24%) Education

High school or under 20 (4.75%) University 301 (71.50%) Graduate school 100 (23.75%) Position level Management level 123 (29.22%) Non-management level 298 (70.78%) Industry High-tech 280 (66.51%) Non-high-tech 121 (28.74%) Others 20 (4.75%) Department

Research and development 48 (11.40%) Human resource/training 13 (3.09%) Finance/accounting 22 (5.23%) Production 174 (41.33%) Sales/service 24 (5.70%) Others 130 (33.25%) Job career 1 year or less 5 (1.19%) 1–5 years 117 (27.79%) 6–10 years 136 (32.30%) 11–15 years 99 (23.52%) 16–20 years 41 (9.74%) 21–25 years 15 (3.56%) 26 years or more 8 (1.90%) Tenure 1 year or less 29 (6.89%) 1–5 years 191 (45.37%) 6–10 years 106 (25.18%) 11–15 years 62 (14.73%) 16–20 years 18 (4.28%) 21–25 years 12 (2.85%) 26 years or more 3 (0.7%)

OCBs are measured using 20 items (four items for each dimension) directly drawn and re-worded from Podsakoff et al. (1990) and Morrison (1994). These items are used for accurately measuring individuals’ citizenship behavior in their organiza-tion. Perceived legal citizenship from the aspect of law is measured using four items modified from Maignan and Ferrell (2000). For example, ‘‘internal policies prevent discrimination in employees’ com-pensation and promotion’’ in previous literature is modified to ‘‘my firm follows the law to prevent discrimination in workplaces’’ in this study. Per-ceived ethical citizenship from the aspect of ethical business practices is measured using four items modified from Maignan and Ferrell (2000). For example, ‘‘our business has a comprehensive code of conduct’’ in previous literature is modified to ‘‘my firm has a comprehensive code of conduct in ethics’’ in this study. Finally, discretionary citizen-ship from the aspect of philanthropism and resource allocation is measured using two items re-worded from Maignan and Ferrell (2000) and another two items re-worded from De los Salmones et al. (2005). For example, ‘‘our business gives adequate contributions to charities’’ in previous literature is reworded to ‘‘my firm gives adequate contributions to charities.’’ These items focus on discretionary issues related to stakeholders outside the firm rather than its employees. All the measurement items are listed in the Appendix.

Data analysis

The survey data were analyzed using a two-step structural equation modeling (SEM) approach pro-posed by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). The first step performs confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on all data collected to assess scale reliability and valid-ity. The second step examines path effects and sig-nificances in the hypothesized structural model for purposes of testing the hypotheses. Test results from each stage of analysis are presented next.

Measurement model testing

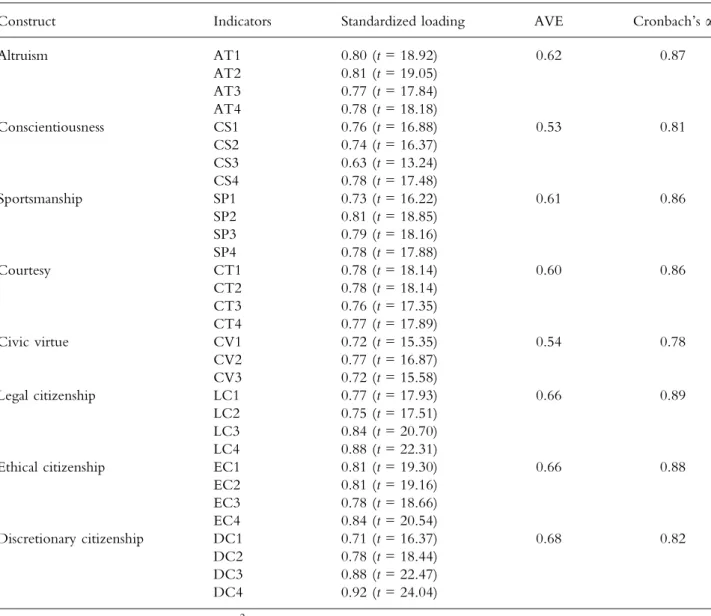

CFA analysis was performed on all items corre-sponding to the eight constructs measured in

Likert-type scales. The goodness-of-fit of the CFA model was assessed using a variety of fit metrics, as shown in TableII. The normalized chi-square (chi-square/degrees of freedom) of the CFA model was smaller than the recommended value of 2.0. Whereas the root mean square residual (RMR) was smaller than 0.05, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was smaller than 0.08. Furthermore, the comparative fit index (CFI), the non-normed fit index (NNFI), the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-of-goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), and the normed fit index (NFI) all exceeded 0.90. These figures suggest that the hypothesized CFA model in this study fits well within the empirical data.

Convergent validity was assessed using three criteria recommended by Fornell and Larcker (1981). First, as evident from the t-statistics listed in Table II, all factor loadings were statistically sig-nificant at p < 0.001, which is the first requirement to assure convergent validity of construct (Ander-son and Gerbing, 1988). Second, the average var-iance extracted (AVE) for all constructs exceeded or equaled 0.50, indicating that the overall hypothesized items capture sufficient variance in the underlying construct than that attributable to measurement error (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Third, the reliabilities for each construct exceeded 0.70 (see TableIII), satisfying the general require-ment of reliability for research instrurequire-ments. At any rate, the empirical data collected by this study meet all three criteria required to assure convergent validity.

Discriminate validity was assessed by chi-square difference tests between an unconstrained model, where all constructs in our CFA model were allowed to co-vary freely with constrained models and where covariance between each pair of constructs is fixed at one. The advantage of this technique is its simulta-neous pair-wise comparisons for the constructs based on the Bonferroni method. Controlling for the experiment-wise error rate by setting the overall significance level to 0.01, the Bonferroni method indicated that the critical value of the chi-square difference should be 12.74. Chi-square difference statistics for all pairs of constructs exceeded this critical value of 12.74 (see Table III), thereby assuring discriminate validity for our data sample. Overall, the test results herein indicate that research

instruments used for measuring the constructs of interest in this study are statistically adequate.

Structural model testing

The second step transforms the CFA model to a structural model that reflects the hypothesized asso-ciations described in our research model for purposes of testing the hypotheses. TableIV shows the test results of this analysis.

Results

Twelve out of our 15 paths in our structural models were significant at the p < 0.01 or p < 0.01 signif-icance levels, and these empirical test results show that only hypothesis H3 is partially supported, while hypotheses H1 and H2 are fully supported in this study. The insignificant model paths (i.e., H3b, H3c, and H3e) indicate that perceived discretionary citi-zenship does not always help OCBs, also suggesting that management strategies for conducting corporate

TABLE II

Standardized loadings and reliabilities

Construct Indicators Standardized loading AVE Cronbach’s a

Altruism AT1 0.80 (t = 18.92) 0.62 0.87 AT2 0.81 (t = 19.05) AT3 0.77 (t = 17.84) AT4 0.78 (t = 18.18) Conscientiousness CS1 0.76 (t = 16.88) 0.53 0.81 CS2 0.74 (t = 16.37) CS3 0.63 (t = 13.24) CS4 0.78 (t = 17.48) Sportsmanship SP1 0.73 (t = 16.22) 0.61 0.86 SP2 0.81 (t = 18.85) SP3 0.79 (t = 18.16) SP4 0.78 (t = 17.88) Courtesy CT1 0.78 (t = 18.14) 0.60 0.86 CT2 0.78 (t = 18.14) CT3 0.76 (t = 17.35) CT4 0.77 (t = 17.89) Civic virtue CV1 0.72 (t = 15.35) 0.54 0.78 CV2 0.77 (t = 16.87) CV3 0.72 (t = 15.58) Legal citizenship LC1 0.77 (t = 17.93) 0.66 0.89 LC2 0.75 (t = 17.51) LC3 0.84 (t = 20.70) LC4 0.88 (t = 22.31)

Ethical citizenship EC1 0.81 (t = 19.30) 0.66 0.88 EC2 0.81 (t = 19.16) EC3 0.78 (t = 18.66) EC4 0.84 (t = 20.54) Discretionary citizenship DC1 0.71 (t = 16.37) 0.68 0.82 DC2 0.78 (t = 18.44) DC3 0.88 (t = 22.47) DC4 0.92 (t = 24.04)

Goodness-of-fit indices (n = 421): v4062 = 670.91 (p-value < 0.001); NNFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.91; CFI = 0.96;

discretionary citizenship should be carefully exam-ined before smooth interorganizational communi-cation and educommuni-cation regarding CSR between corporate authorities and employees are provided. Nevertheless, the unexpected results for the partially supported hypothesis H3 may warrant further study so that the insights behind the insignificant models paths can be interpreted accurately.

Discussion

Implications for research

One of the empirical findings of this study indicates the positive influence of perceived legal citizenship and perceived ethical citizenship on OCBs due to social identity, further complementing some previ-ous research that empirically tests the effectiveness of corporate citizenship to generate goodwill toward the firm (e.g., Murray and Vogel, 1997). This finding makes this study an important bridge between legal and ethical citizenship perceived by employees and their subsequent OCBs, because much previous research links corporate citizenship to certain positive outcomes only related to cus-tomers’ or financial profits without taking employees into consideration (e.g., Becker-Olsen et al., 2006). A unique finding that has not been found in any of previous research is that perceived discretionary citizenship has negative effects on two dimensions of OCBs, namely altruism and courtesy. The finding of this study presents a new direction for future

TABLE III

Chi-square difference tests for examining discriminate validity

Construct pair

v4062 = 670.91 (unconstrained model)

v4072 (constrained model) v2difference

(F1, F2) 983.69*** 312.78 (F1, F3) 1364.15*** 693.24 (F1, F4) 969.26*** 298.35 (F1, F5) 910.14*** 239.23 (F1, F6) 1181.94*** 511.03 (F1, F7) 1280.76*** 609.85 (F1, F8) 1409.80*** 738.89 (F2, F3) 1330.39*** 659.48 (F2, F4) 943.36*** 272.45 (F2, F5) 854.76*** 183.85 (F2, F6) 1074.36*** 403.45 (F2, F7) 1112.73*** 441.82 (F2, F8) 1165.27*** 494.36 (F3, F4) 1268.97*** 598.06 (F3, F5) 1000.68*** 329.77 (F3, F6) 1345.77*** 674.86 (F3, F7) 1355.05*** 684.14 (F3, F8) 1701.88*** 1030.97 (F4, F5) 857.13*** 186.22 (F4, F6) 1145.93*** 475.02 (F4, F7) 1197.60*** 526.69 (F4, F8) 1582.21*** 911.30 (F5, F6) 876.95*** 206.04 (F5, F7) 849.02*** 178.11 (F5, F8) 953.29*** 282.38 (F6, F7) 1116.82*** 445.91 (F6, F8) 1366.15*** 695.24 (F7, F8) 1144.56*** 473.65 F1, altruism; F2, conscientiousness; F3, sportsmanship; F4, courtesy; F5, civic virtue; F6, legal citizenship; F7, ethical citizenship; F8, discretionary citizenship.

***Significant at the 0.001 overall significance level by using the Bonferroni method.

TABLE IV

Path coefficients and t value

Hypothesis Standardized coefficient t value H1a: F6 fi F1 0.51** 7.43 H2a: F7 fi F1 0.27** 3.51 H3a: F8 fi F1 -0.21** -3.27 H1b: F6 fi F2 0.40** 5.53 H2b: F7 fi F2 0.22** 2.63 H3b: F8 fi F2 -0.05 -0.71 H1c: F6 fi F3 0.22** 2.93 H2c: F7 fi F3 0.18* 2.09 H3c: F8 fi F3 -0.13 -1.81 H1d: F6 fi F4 0.45** 6.60 H2d: F7 fi F4 0.30** 3.91 H3d: F8 fi F4 -0.14* -2.09 H1e: F6 fi F5 0.35** 5.13 H2e: F7 fi F5 0.49** 6.09 H3e: F8 fi F5 -0.10 -1.57 F1, altruism; F2, conscientiousness; F3, sportsmanship; F4, courtesy; F5, civic virtue; F6, legal citizenship; F7, ethical citizenship; F8, discretionary citizenship.

research to further evaluate the potential side effects of corporate citizenship in influencing OCBs. Par-ticularly, previous research related to resource allo-cation seldom examines how a firm’s corporate citizenship leads to its employees’ negative response toward the firm due to perceptually reduced resources. These negative effects of perceived dis-cretionary citizenship found in this study may have a theoretical explanation. Keim (1978) describes some corporate citizenship activities (e.g., discretionary ones) as ‘‘investments’’ in a public good, suggesting that a firm has to first allocate their resources to enhance the benefits of general public rather than those of their own employees. The negative influ-ence of perceived discretionary citizenship on altruism suggests that employees may mutter against the activities unrelated to the good of their organi-zation, weakening their behavior in helping others in the job context. The negative influence of per-ceived discretionary citizenship on courtesy suggests that employees may grumble about their organiza-tion due to unfavorable discreorganiza-tionary activities toward them. Of course, the empirical findings do not overthrow traditional wisdom regarding the necessity of doing discretionary social responsibility, but just point out the importance of simultaneously taking both positive and negative effects into ac-count in the research areas of corporate citizenship and OCBs.

Collectively, both positive and negative effects of corporate citizenship suggest that management should do their best to meet different needs of employees from various viewpoints to devote re-sources and achieve corporate citizenship in the society. Note that the negative effects of perceived discretionary citizenship found in this study do not necessarily advocate ignoring the discretionary cor-porate citizenship. In fact, management should facilitate efficient communication about the discre-tionary activities between the organization and its employees before the discretionary citizenship is conducted so that such negative effects may be gradually eliminated. To sum up, corporate citi-zenship is the spirits in which organizations have to seek the balance among legal, ethical and discre-tionary behaviors, and the consensus for such bal-ance must be achieved through the mutual understanding between the organizations and their employees.

Implications for practice

Previous research has almost examined the business implications and nature of corporate citizenship in contexts of the North America (Maignan and Ferrell, 2000). Given the globalization of business activities, more and more organizations need to gain hindsight into the desirability and nature of corpo-rate citizenship in different countries (Maignan and Ferrell, 2000). For that reason, this study provides empirical findings and implications of corporate citizenship in the business contexts of Taiwan, sub-stantially complementing previous research.

The test results show that OCBs can be directly and completely improved by strengthening the ef-forts of the organization in terms of legal and ethical practices – that is, OCBs cannot be arbitrarily obtained, but rather they can be achieved after employees observe in depth their firm’s legal and ethical actions. The double-track perspective (i.e., the influence of both legal and ethical citizenship on OCBs) is quite different from traditional literature that purely focuses on workplace culture or incen-tives in affecting OCBs without recognizing the influence of firms’ social responsibilities. Organiza-tions that are unable to show legal and ethical citi-zenship in the long run are unlikely to boost their employees’ OCBs due to weak identification of the employees. This is understandable because employ-ees’ identification toward their organization refers to the process by which beliefs about the organization become self-defining (Brown, 2006). When good corporate legal and ethical citizenship perceived by employees are internalized, employees see them-selves as personifying the organization, leading to their OCBs in the organization due to the positive self-concept.

The negative influence of perceived discretionary citizenship on two dimensions of OCBs (i.e., altru-ism and courtesy) suggests that particular corporate citizenship could sometimes backfire in the form of negative impacts on the employees’ citizenship behavior. Organizations could be in great danger when they adopt a high-effort discretionary citizen-ship profile that scales down the existing interest of employees or other stakeholder groups (e.g., inves-tors). This phenomenon also suggests that manage-ment should provide education or training in social responsibility issues to facilitate an efficient dialog

between organization authorities and the employees given that business organizations often talk to their employees, but mostly keep quiet about the results (Burchell and Cook, 2006). The negative effect of perceived discretionary citizenship could also be attributed to the incapability of such citizenship to produce perceptual incentives, returns, or stimula-tion to employees in the short term. Although it is a must that management conducts all-round corporate citizenship, the most important thing is to do it at the right time after mutual understanding about social responsibility between the firms and their employees is obtained. Management should disseminate the firm’s vision of corporate citizenship through internal organizational channels to its members and ultimately strengthen the OCBs and lessen the negative side effects of such corporate citizenship. Taking discre-tionary citizenship, for example, management may demonstrate examples of discretionary citizenship from benchmarking organizations across industries for employees to learn about the obligatory duties of the organization and also clarify the resource alloca-tion of which the employees may have misappre-hension about.

In summary, management should know that employees are very sensitive to any confusion about corporate citizenship actions. Once management has detected employees’ doubts concerning CSR, management should further fortify the OCBs by transcribing business activities and verifying such activities as beneficial to society, employees, and the organization. Management must experience OCBs’ formation as a complex process owing to the underlying nature of a significant influence of dif-ferent antecedents on OCBs. Last but not least, good communication with employees helps for learning perceived corporate citizenship and only the con-sensus about citizenship in the entire organization can ultimately bring about fruitful OCBs.

Limitations of the study

This study contains three limitations related to the measurements and interpretations of the results. The first limitation of this study is its generalizability owing to the highly delimited nature of the subject sample in the single country setting of Taiwan. In-deed, given that employees’ understanding and

support about different dimensions of social responsibility may somewhat vary for different nations, the applications based on the empirical findings of this study to other countries should be used with caution. Particularly, cultural psycholo-gists suggest that cultural differences across nations can influence the perceived importance of corporate citizenship among organizational members.

The second limitation is the possibility of com-mon method bias, given that the predictors in the research model were measured perceptually at a single point in time. To test for this bias, this study conducted the single factor test of Harman (Pod-sakoff and Organ, 1986). In this test, if substantial common method variance is present in the data sample, then either a single factor will emerge from the factor analysis or a general factor will account for the majority of the covariance in the indepen-dent and depenindepen-dent variables. Exploratory factor analysis of measurement items for the five constructs in the survey reveals the seven factors explaining 14.39%, 13.21%, 12.97%, 12.96%, 12.69%, 12.54%, 11.97%, and 9.27% of the total variance, respec-tively. These figures suggest that the variances are not distributed unevenly among multiple factors, suggesting that potential common method bias is not a threat herein for subsequent analysis. Note that we do not ascertain the complete avoidance of the common method bias given that none of existing statistical methods today can accurately detect the common method bias (Podsakoff and Organ,1986). Nevertheless, it is still a must that we use the Harman’s method to present that the threat of comment method bias is not serious threats to evaluation of the hypotheses, suggested strongly by many prior studies.

Finally, this study did not address other institu-tional factors, such as workplace cultures, working environment, working hours, organizational values, firm sizes, etc. Future studies can improve these shortcomings by including a variety of control variables for further empirical tests and also by observing research subjects over time so that the genuine effects of corporate citizenship on OCBs can be transparently presented from a longitudinal perspective. In addition, future research may split employees into different groups based on OCBs (low OCBs versus high OCBs) so as to better discern what factors result in strong OCBs.

Appendix: Measurement items Altruism

AT1. I help others who have been absent. AT2. I help others who have heavy work loads. AT3. I help orient new people even though it is not required.

AT4. I willingly help others who have work-re-lated problems.

Conscientiousness

CS1. I do not spend time on personal calls. CS2. I do not engage in non-work-related talk. CS3. I will come to work early if needed. CS4. I obey company rules and regulations even when no one is watching.

Sportsmanship

SP1. I often consume a lot of time complaining about trivial matters. (R)

SP2. I often focus on what’s wrong, rather than the positive side. (R)

SP3. I tend to make ‘‘mountains out of mole-hills.’’ (R)

SP4. I often find fault with what the organiza-tion is doing. (R)

Courtesy

CT1. I try to avoid creating problems for co-workers.

CT2. I consider the impact of my actions on co-workers.

CT3. I attend voluntary functions. CT4. I help organize get-togethers. Civic virtue

CV1. I attend functions that are not required, but help the company image.

CV2. I keep abreast of changes in the organiza-tion.

CV3. I read and keep up with organization announcements, memos, and so on.

CV4. I often assess what is best for the firm.

Perceived legal citizenship

LE1. The managers of my firm can comply with the law.

LE2. My firm follows the law to prevent dis-crimination in workplaces.

LE3. My firm always fulfills its obligations of contracts.

LE4. My firm always seeks to respect all laws regulating its activities.

Perceived ethical citizenship

ET1. My firm has a comprehensive code of conduct in ethics.

ET2. Fairness toward co-workers and business partners is an integral part of the employee eval-uation process in my firm.

ET3. My firm provides accurate information to its business partners.

ET4. We are recognized as a company with good business ethics.

Perceived discretionary citizenship

DI1. My firm gives adequate contributions to charities.

DI2. My firm sponsors partnerships with local schools or institutions.

DI3. My firm sponsors local sports or cultural activities.

DI4. My firm sponsors to improve the public well-being of society.

References

Anderson, J. C. and D. W. Gerbing: 1988, ‘Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach’, Psychological Bulletin 103(3), 411–423.

Appelbaum, S. H., G. D. Iaconi and A. Matousek: 2007, ‘Positive and Negative Deviant Workplace Behaviors: Causes, Impacts, and Solutions’, Corporate Governance 7(5), 586–598.

Backhaus, K., B. Stone and K. Heiner: 2002, ‘Exploring the Relationship Between Corporate Social Perfor-mance and Employer Attractiveness’, Business and Society 41(3), 292–318.

Bagnoli, M. and S. Watts: 2003, ‘Selling to Socially Responsible Consumers: Competition and the Private Provision of Public Goods’, Journal of Economics and Management Strategy 12(3), 419–445.

Baker, T. L., T. G. Hunt and M. C. Andrews: 2006, ‘Promoting Ethical Behavior and Organizational Cit-izenship Behaviors: The Influence of Corporate Eth-ical Values’, Journal of Business Research 59(7), 849–857. Baron, D.: 2001, ‘Private Politics, Corporate Social Responsibility and Integrated Strategy’, Journal of Eco-nomics and Management Strategy 10(1), 7–45.

Becker-Olsen, K. L., B. A. Cudmore and R. P. Hill: 2006, ‘The Impact of Perceived Corporate Social Responsibility on Consumer Behavior’, Journal of Business Research 59(1), 46–53.

Berger, I. E., P. H. Cunningham and M. E. Drumwright: 2006, ‘Identity, Identification, and Relationship Through Social Alliances’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34(2), 128–137.

Bergeron, D. M.: 2007, ‘The Potential Paradox of Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Good Citizens at What Cost?’, Academy of Management Review 32(4), 1078–1095.

Brammer, S., A. Millington and B. Rayton: 2007, ‘The Contribution of Corporate Social Responsi-bility to Organizational Commitment’, International Journal of Human Resource Management 18(10), 1701– 1719.

Brown, A. D.: 2006, ‘A Narrative Approach to Col-lective Identities’, Journal of Management Studies 43(4), 731–753.

Brown, T. J., P. A. Dacin, M. G. Pratt and D. A. Whetten: 2006, ‘Identity, Intended Image, Construed Image, and Reputation: An Interdisciplinary Frame-work and Suggested Terminology’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 34(2), 99–106.

Burchell, J. and J. Cook: 2006, ‘It’s Good to Talk? Examining Attitudes Towards Corporate Social Responsibility Dialogue and Engagement Processes’, Business Ethics: A European Review 15(2), 154–170. Carroll, A. B.: 1979, ‘A Three-Dimensional Conceptual

Model of Corporate Performance’, Academy of Man-agement Review 4(4), 497–505.

De los Salmones, M. D. M. G., A. H. Crespo and I. R. del Bosque: 2005, ‘Influence of Corporate Social Responsibility on Loyalty and Valuation of Services’, Journal of Business Ethics 61(4), 369–385.

Dutton, J. E., J. M. Dukerich and C. V. Harquail: 1994, ‘Organizational Images and Member Identification’, Administrative Science Quarterly 39, 239–263.

Elsbach, K.: 1999, ‘An Expanded Model of Organiza-tional Identification’, in R. Sutton and B. Staw (eds.),

Research in Organizational Behavior, Vol. 21 (JAI Press, Inc, Stanford, CA), pp. 163–199.

Emler, N. and N. Hopkins: 1990, ‘Reputation, Social Identity and the Self’, in D. Abrams and M. A. Hogg (eds.), Social Identity Theory – Constructive and Critical Advances (Harvester Wheatsheaf, Hemel Hempstead).

Fornell, C. and D. F. Larcker: 1981, ‘Evaluating Struc-tural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error’, Journal of Marketing Research 18(1), 39–50.

Freedman, S. M. and J. R. Montanari: 1980, ‘An Inte-grative Model of Managerial Reward Allocation’, Academy of Management Review 5(3), 381–390. Greening, D. W. and D. B. Turban: 2000, ‘Corporate

Social Performance as a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Work Force’, Business and Society 39(3), 254–280.

Grit, K.: 2004, ‘Corporate Citizenship: How to Strengthen the Social Responsibility of Managers?’, Journal of Business Ethics 53(1/2), 97–106.

He, Y., Z. Tian and Y. Chen: 2007, ‘Performance Implications of Nonmarket Strategy in China’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management 24(2), 151–169.

Hillman, A. J. and G. D. Keim: 2001, ‘Shareholder Value, Stakeholder Management, and Social Issues: What’s the Bottom Line?’, Strategic Management Journal 22(2), 125–139.

Hockey, G. R. J.: 1997, ‘Compensatory Control in the Regulation of Human Performance Under Stress and High Workload: A Cognitive-Energetical Frame-work’, Biological Psychology 45, 73–93.

Jeurissen, R.: 2004, ‘Institutional Conditions of Corpo-rate Citizenship’, Journal of Business Ethics 53(1/2), 87–96.

Johnson, R. E. and C. H. Chang: 2006, ‘‘‘I’’ is to Continuance as ‘‘We’’ is to Affective: The Relevance of the Self-Concept for Organizational Commitment’, Journal of Organizational Behavior 27(5), 549–570.

Joyner, B. E. and D. Payne: 2002, ‘Evolution and Implementation: A Study of Values, Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility’, Journal of Busi-ness Ethics 41(4), 297–311.

Keim, G. D.: 1978, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility: An Assessment of the Enlightened Self-Interest Model’, Academy of Management Review 3(1), 32–39.

Kell, G.: 2005, ‘The Global Compact Selected Experi-ences and Reflections’, Journal of Business Ethics 59(1/2), 69–79.

Kristoffersen, I., P. Gerrans and M. Clark-Murphy: 2009, ‘Corporate Social Performance and Financial

Perfor-mance’, Accounting, Accountability & Performance 14(2), 45–90.

Lam, M. L. L.: 2009, ‘Beyond Credibility of Doing Business in China: Strategies for Improving Corporate Citizenship of Foreign Multinational Enterprises in China’, Journal of Business Ethics 87(1), 137–146. Lantos, G. P.: 2002, ‘The Ethicality of Altruistic

Cor-porate Social Responsibility’, Journal of Consumer Marketing 19(3), 205–230.

Luo, X. and C. B. Bhattacharya: 2006, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value’, Journal of Marketing 70(1), 1–18.

Maignan, I. and O. C. Ferrell: 2000, ‘Measuring Cor-porate Citizenship in Two Countries: The Case of the United States and France’, Journal of Business Ethics 23(3), 283–297.

Maignan, I. and O. C. Ferrell: 2004, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing: An Integrative Frame-work’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32(1), 3–19.

Margolis, J. D. and J. P. Walsh: 2003, ‘Misery Loves Companies: Rethinking Social Initiatives by Business’, Administrative Science Quarterly 48(2), 268–305. Maxfield, S.: 2008, ‘Reconciling Corporate Citizenship

and Competitive Strategy: Insights from Economic Theory’, Journal of Business Ethics 80(2), 367–377. Mescher, B. R.: 2008, ‘The Business of Commercial Legal

Advice and the Ethical Implications for Lawyers and Their Clients’, Journal of Business Ethics 81(4), 913–926. Morrison, E. W.: 1994, ‘Role Definitions and Organi-zational Citizenship Behavior: The Importance of the Employee’s Perspective’, Academy of Management Jour-nal 37(6), 1543–1567.

Murray, K. B. and C. M. Vogel: 1997, ‘Using a Hierarchy-of-Effects Approach to Gauge the Effectiveness of Corporate Social Responsibility to Generate Goodwill Toward the Firm: Financial Versus Nonfinancial Im-pacts’, Journal of Business Research 38(2), 141–159. O’Shaughnessy, K. C., E. Gedajlovic and P. Reinmoeller:

2007, ‘The Influence of Firm, Industry and Network on the Corporate Social Performance of Japanese Firms’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management 24(3), 283–303.

Okoye, A.: 2009, ‘Theorising Corporate Social Responsibility as an Essentially Contested Concept: Is a Definition Necessary?’, Journal of Business Ethics 89(4), 613–628.

Organ, D. W.: 1988, Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Good Soldier Syndrome (Lexington Books, Lex-ington, MA).

Orlitzky, M., F. Schmidt and S. Rynes: 2003, ‘Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis’, Organization Studies 24(3), 403–441.

Peterson, D. K.: 2004, ‘The Relationship Between Perceptions of Corporate Citizenship and Organiza-tional Commitment’, Business and Society 43(3), 296–319.

Podsakoff, P. M. and S. B. MacKenzie: 1997, ‘The Im-pact of Organizational Citizenship Behaviors on Organizational Performance: A Review and Sugges-tions for Future Research’, Human Performance 10, 133–151.

Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, R. H. Moorman and R. Fetter: 1990, ‘Transformational Leader Behaviors and Their Effects on Followers’ Trust in Leader, Sat-isfaction, and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors’, The Leadership Quarterly 1(2), 107–142.

Podsakoff, P. M. and D. W. Organ: 1986, ‘Self-Reports in Organizational Research: Problems and Prospects’, Journal of Management 12(4), 531–544.

Reynolds, N., A. Diamantopoulos and B. B. Schle-gelmilch: 1993, ‘Pretesting in Questionnaire Design: A Review of the Literature and Suggestions for Further Research’, Journal of the Market Research Society 35(2), 171–182.

Roberts, P. W. and G. R. Dowling: 2002, ‘Corporate Reputation and Sustained Superior Financial Perfor-mance’, Strategic Management Journal 23(12), 1077–1093. Siegel, D. S. and D. F. Vitaliano: 2007, ‘An Empirical Analysis of the Strategic Use of Corporate Social Responsibility’, Journal of Economics & Management Strategy 16(3), 773–792.

Torres-Baumgarten, G. and V. Yucetepe: 2009, ‘Multi-national Firms’ Leadership Role in Corporate Social Responsibility in Latin America’, Journal of Business Ethics 85(1), 217–224.

Turnipseed, D. L.: 2002, ‘Are Good Soldiers Good? Exploring the Link Between Organization Citizenship Behavior and Personal Ethics’, Journal of Business Research 55(1), 1–15.

Turnipseed, D. L.: 2009, ‘From Discretionary to Re-quired’, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 15(3), 201–216.

Van Staden, C.: 2009, ‘Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in Developing Countries – The Case of Bangladesh’, British Accounting Review 41(2), 138–139. Whetten, D. A. and A. Mackey: 2002, ‘A Social Actor Conception of Organizational Identity and its Impli-cations for the Study of Organizational Reputation’, Business & Society 41(1), 393–414.

Wood, D.: 1991, ‘Corporate Social Performance Revis-ited’, Academy of Management Review 16(4), 691–718. Zahra, S. A. and M. S. LaTour: 1987, ‘Corporate Social

Responsibility and Organizational Effectiveness: A Multivariate Approach’, Journal of Business Ethics 6(6), 459–467.

Chieh-Peng Lin Institute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: jacques@mail.nctu.edu.tw Nyan-Myau Lyau Graduate School of Technological and Vocational Education, National Yunlin University of Science and Technology, Yunlin, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: lyaunm@yuntech.edu.tw Yuan-Hui Tsai Department of Finance, Chihlee Institute of Technology, Taipei, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: tsaimalo@gmail.com

Wen-Yung Chen Department of Education, National Taichung University, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: foxgolf@gmail.com Chou-Kang Chiu National Taichung University, Graduate Institute of Business Administration, Taichung, Taiwan, R.O.C. E-mail: ckchiu@ntu.edu.tw