邁向人權國家?陳水扁與馬英九的人權政策比較 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 邁向人權國家?陳水扁與馬英九的人權政策比較 Towards a Human Rights State? A Comparison of Taiwan’s Human Rights Policies under Chen Shui-bian and Ma Ying-jeou 研究生:丹趵曼 Student: Daniel Bowman 指導教授:廖福特 Advisor: Dr Fort Fu-te Liao 國立政治大學. 學. 亞太研究英語碩士學位學程 碩士論文. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. A Thesis. engchi. i n U. v. Submitted to the International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific Studies National Chengchi University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Master of Arts in Taiwan Studies. 中華民國九十九年七月 July 2010.

(3) Abstract This thesis examines Taiwan’s human rights development from 2000 until 2010. It looks at and compares the policies and action of Presidents Chen Shui-bian and Ma Ying-jeou in terms of three indicators of human rights: the implementation of the international human rights treaties (ICCPR and ICESCR), the establishment of a national human rights commission and the status of the death penalty. The case of Australia and its position in relation to the three key areas of this human rights study. 治 政 human rights milestones and the beginnings大 of Taiwan’s democratization 立 are introduced by way of an overview but the focus of this thesis is on the are analyzed for comparative purposes. Additionally, important historical. ‧ 國. 學. events of the last decade. In doing so, the overall aim of this study is to assess whether Taiwan has achieved its stated goal of becoming a human. ‧. rights state.. sit. y. Nat. er. io. Keywords: Human Rights; Taiwan; International Human Rights. n. Covenants; NationalaHuman Rights Commission; Death Penalty. iv l C n hengchi U. i.

(4) Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Dr Fort Fu-te Liao of Academia Sinica for agreeing to take on an external student. His assistance, insight and encouragement have been invaluable. I sincerely appreciate his efforts and recognize that this thesis is of a higher standard having had Prof. Liao on board.. I am very grateful to my thesis committee members, Prof. Mab Huang of Soochow University and Dr Hui-Yen Hsu of Dong Hwa University for their comments and feedback, which have been both humbling and constructive. I also thank Dr MengChang Yao of Fujen University for examining my thesis proposal.. 政 治 大 My studies in Taiwan have been generously supported by the Democratic Pacific 立. Union. I am honoured to have been a recipient of the DPU Scholarship and would like. ‧ 國. 學. to acknowledge the organization’s leader, Annette Lu. DPU’s orientation activities and support have greatly assisted me in becoming acquainted with Taiwan’s human. ‧. rights and democracy movement and have made a positive contribution to my studies.. y. Nat. sit. I also must sincerely thank Ms Lin Hsin-yi, Executive Director of the TAEDP.. er. io. Without her, I may never have found my supervisor and for this, I am indebted to her.. al. n. v i n C habout the abolitionUof the death penalty in Taiwan. their continued efforts to bring engchi. I wish her and the Taiwan Alliance to End the Death Penalty (TAEDP) the best in. I would like to thank my professors, particularly Prof. Nancy Hsiao-Hung Chen and Prof. David Blundell for their assistance throughout my studies. My heartfelt thanks also go to Ms Carol Hsieh, our beloved program administrator. To my NCCU classmates, your camaraderie, your stories and views and your friendship have made these two years all the more rewarding.. I am also grateful to my past professors at the University of Queensland, especially to Ms Shirley Liu and Dr Daphne Hsieh who recommended I consider studying in Taiwan.. ii.

(5) To my friends both in Taipei and beyond, your support has kept me focused throughout this, at times stressful, period. Although too many to mention individually, Regina Martinez Enjuto and Tigh Chen deserve special mention. Their assistance and constant support I cannot quantify.. Last but not least, I thank my family. Their encouragement, support and love have made me the person that I am. I am sure the distance between Taipei and Brisbane and my extended absences have not been easy but you have wholeheartedly supported my student endeavours and ambitions. I could not have done this without you all. To my Mum, I say thank you for fostering in me a love of learning and of life. To my Dad, I thank him for instilling in me the belief that you can be the best at anything. 治 政 大 me a truly fortunate grandson. 立. you put your mind to. And to my Grandma, her affection and sounding board make. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(6) TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………… 1.1. Purposes of the research ……………………………………………… 1.2. Motivation ……………………………………………………………… 1.3. Methodology ……………………………………………………………… 1.4. Overview of the three indicators ……………………………………… 1.4.1. Implementing international standards domestically ……………… 1.4.2. The importance of NHRCs ……………………………………… 1.4.3. International death penalty trends ………………………………. 1 1 2 2 4 5 5 7. 2. The Australian model of human rights development ……………………… 2.1. Introduction ……………………………………………………………… 2.1.1. Why Australia? ……………………………………………… 2.2. Australia’s progress in the first indicator ……………………………… 2.2.1. Ratification ……………………………………………………… 2.2.2. The ICESCR ……………………………………………………… 2.2.3. Direct implementation of the ICCPR……………………………… 2.2.4. Indirect compliance ……………………………………………… 2.2.5. Reporting and Individual Complaints ……………………… 2.2.6. Concluding remarks on the ICCPR in Australia ……………… 2.3. The second indicator – Australia’s national human rights institutions … 2.3.1. Establishment of NHRCs ……………………………………… 2.3.2. Composition of the NHRC ……………………………………… 2.3.3. Powers and duties ……………………………………………… 2.3.4. State and Territory NHRCs ……………………………………… 2.3.5. Assessment of Australia’s NHRCs ……………………………… 2.4. The third indicator – death penalty in Australia ……………………… 2.4.1. Abolition in Australia ……………………………………… 2.4.2. Recent developments – opposition confirmed ……………… 2.4.3. Public opinion on the death penalty ……………………………… 2.5. Overview of Australia’s human rights ………………………………. 9 9 9 10 11 11 12 15 16 17 17 17 18 18 19 20 20 20 21 22 23. 3. Human Rights in Taiwan before 2000 ……………………………………… 3.1. The Martial Law period and ‘White Terror’ ……………………………… 3.1.1. Oppression ………………………………………………… 3.1.2. Government crackdowns ……………………………………… 3.1.3. The extent of the terror ……………………………………… 3.1.4. Reflections on this period ……………………………………… 3.2. The path to democratization ……………………………………………… 3.2.1. Civil and political rights ……………………………………… 3.2.2. Absence of human rights policy ……………………………… 3.3. Historical consideration of the three indicators ……………………… 3.3.1. International human rights standards ……………………………… 3.3.2. A national human rights commission ……………………… 3.3.3. Death penalty ……………………………………………………… 3.4. Historical overview ………………………………………………………. 25 25 27 28 29 29 31 31 32 32 32 33 34 34. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv. i n U. v.

(7) 4. Human Rights under Chen Shui-bian ……………………………………… 4.1. Introduction – a new era of human rights ……………………………… 4.1.1. The Presidential Human Rights Advisory Group ……………… 4.1.2. The Human Rights White Paper ……………………………… 4.2. First indicator progress – attempts to implement international standards domestically ……………………………………………………………… 4.2.1. Initial intentions and actions ……………………………………… 4.2.2. The White Paper on international human rights standards ……… 4.2.3. Legislative attempts ……………………………………………… 4.2.4. Difficulties encountered ……………………………………… 4.4.5. Efforts post-2004 ……………………………………………… 4.3. Plans for a National Human Rights Commission ……………………… 4.3.1. The White Paper’s proposals ……………………………………… 4.3.2. Draft legislation ……………………………………………… 4.3.3. Second term and hopes of a NHRC fade ……………………… 4.4. Policy towards the death penalty and progress towards abolition ……… 4.4.1. The administration’s position on abolition ……………………… 4.4.2. Legislation and the death penalty ……………………………… 4.4.3. Executive action ……………………………………………… 4.4.4. Conclusion – Gradual abolition ……………………………… 4.5. Overall Conclusions – Chen’s human rights legacy ………………………. 立. 政 治 大. 36 36 37 37 38 39 40 42 45 45 46 47 48 49 50 50 51 52 53 54. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. 5. Human Rights under Ma Ying-jeou ……………………………………… 57 5.1. Ma’s presidency and overview of his human rights policy ……………… 57 5.2. Implementation of international standards ……………………………… 58 5.2.1. Ratification of the ICCPR and ICESCR ……………………… 59 5.2.2. Domestic legislation ……………………………………………… 59 5.3. A National Human Rights Commission ……………………………… 62 5.3.1. NHRC discussions ……………………………………………… 63 5.3.2. Opposition and support ……………………………………… 63 5.4. Ma and the death penalty ……………………………………………… 64 5.4.1. Appointment of Wang Ching-feng – de facto moratorium continues 64 5.4.2. Controversy and resignation ……………………………………… 67 5.4.3. New Justice Minister and resumption of executions ……………… 69 5.5. Future directions and conclusions ……………………………………… 72. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 6. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………… 6.1. First indicator assessment ……………………………………………… 6.2. Second indicator assessment ……………………………………………… 6.3. Third indicator assessment ……………………………………………… 6.4. Towards a human rights state? ……………………………………… References. 74 74 75 76 78. ……………………………………………………………… 80. v.

(8) LIST OF TABLES 1. Methodological Approach ………………………………………… 3 2. Death Penalty in Australia ………………………………………… 21 3. Death Penalty since Political Liberalization ………………………… 34. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(9) 1. Introduction The first decade of the new millennium has been significant for Taiwan in many ways. Taiwan saw its first change of ruling party with the election of Chen Shui-bian in 2000 and after two terms, a KMT president, Ma Ying-jeou was convincingly returned to that office. Building on the significant progress since the lifting of martial law and start of the path to democracy, this thesis will examine the human rights developments in Taiwan from 2000-2010 and compare the policies of the respective presidents. In a relatively short period of time, Taiwan has built up a considerable civil society and human rights awareness and as such, governments of both sides have voiced support for human rights and their continued promotion and protection in Taiwan. Indeed, the then-President Chen promised to lead Taiwan in becoming a. 政 治 大 developments under Chen and Ma. By examining the human rights progress and 立. human rights state. This thesis will attempt to evaluate this promise by comparing. pitfalls of the last decade, it is hoped to bring further attention to this very important. ‧ 國. 學. area of Taiwan’s legal development.. ‧. 1.1. Purposes of the research. y. Nat. The purposes of this research are to explore Taiwan’s human rights by analyzing the. io. sit. question whether Taiwan is moving towards becoming a human rights state. More. er. specifically, its focus is to determine and evaluate the progress made in human rights. al. n. v i n C h to-date. Therefore, administration to President Ma’s e n g c h i U I will compare the policies, in Taiwan from 2000-present and to compare the results of Chen Shui-bian’s. attempts at implementation and achievements of Presidents Chen and Ma across three key areas of human rights during the period 2000-present. Taiwan and its achievements in democratization in recent decades and its emerging development of and interest in human rights merit further academic study. Taiwan’s initial efforts in this area are commendable but further critical examination can only be of additional benefit to those interested in Taiwan’s political development and the human rights of Taiwanese citizens. By looking at the three key areas of international human rights treaties implementation, the establishing of a human rights commission and the status of the death penalty, it is hoped that this research can determine the extent of progress in human rights throughout this decade and to assess the efforts and results of the respective administrations in these areas. In doing so, it is also hoped that this. 1.

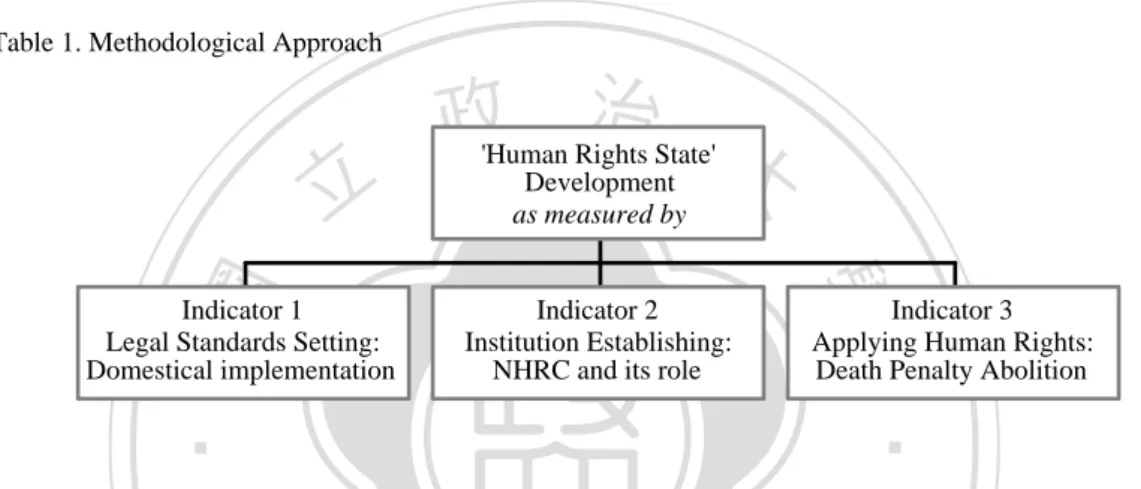

(10) research can contribute to and expand on the body of knowledge in the English language in this area.. 1.2. Motivation Taiwan is a unique country for many reasons. Its unique international status and the hurdles it faces as a result have not stopped it from achieving a peaceful end to authoritarianism and a smooth transition to democracy. The political pressure it faces from an authoritarian yet arguably culturally similar regional and world superpower just across the Taiwan Strait have fortunately not impeded these developments. Some have argued that East Asian values are incompatible with notions of human rights and liberal democracy but Taiwan has shown that this is not the case and that human. 政 治 大 important reasons that Taiwan is the focus of my study in human rights. Moreover, I 立 believe this study can be of use to other countries as they deal with democratization and assist in spreading these hard-fought freedoms.. 學. ‧ 國. rights can be achieved notwithstanding a Confucian cultural legacy. It is for these. ‧. 1.3. Methodology. y. Nat. In order to assess Taiwan’s progress in human rights development and whether it is. sit. moving towards becoming a human rights state, this thesis will examine three human. er. io. rights ‘indicators’, described also above as key areas. For the purposes of this thesis,. al. n. v i n C h are numerousUand can include such aspects as human rights status. These indicators engchi laws, institutions, NGO activity, positions on various issues and public awareness.. human rights ‘indicators’ are defined as objective criteria that can be used to measure. Using indicators makes it clear how human rights progress is being measured and sets a framework that is easy to understand and objective. It has been decided to focus on three indicators: in the area of legal policy and standards setting, the implementation of the major international human rights standards as found in the ICCPR and ICESCR; in the area of institutions, the establishment of a National Human Rights Commission; and, as an example of applying human rights discourse, the controversial issue of the death penalty and its abolition. Human rights development across each three of these indicators will be, therefore, evaluated to arrive at conclusions as to the overall state of Taiwan’s human rights development. Clearly, other indicators could be examined but it is important to find a balance in number and a sufficient breadth to be able to. 2.

(11) best evaluate the research question. It is for this reason the three indicators, which explore diverse areas such as the setting of human rights standards, establishing a means of enforcement and promotion and, an application of human rights in criminal justice, have been chosen. Coomans, Grünfeld and Kamminga discuss the ‘methodological deficit’ in much human rights research to date and outline some useful suggestions to avoid such ‘methodological sloppiness’.1 These recommendations have been followed in arriving at the above-mentioned methodology.. Table 1. Methodological Approach. 政 治 大 'Human Rights State' Development as measured by. Indicator 1 Legal Standards Setting: Domestical implementation. 學. ‧ 國. 立. Indicator 2 Institution Establishing: NHRC and its role. Indicator 3 Applying Human Rights: Death Penalty Abolition. ‧ sit. y. Nat. The examination of these three indicators will be divided into three main areas: foreign comparison, historical background and the domestic situation under Chen and. io. n. al. er. Ma. This thesis will begin by examining the three indicators in a foreign setting. The. i n U. v. case of Australia and its human rights development and consideration of the three. Ch. engchi. indicators will be explored. As a country that has considerable experience in dealing with all three indicators, it will provide an example of how these issues have been treated. Taiwan’s general human rights development (or lack thereof) prior to 2000 will be explored in Chapter 3. The lack of progress across the chosen three indicators will be examined and possible reasons given. Other indicators of human rights suppression and progress will be briefly introduced to provide a background to human rights in this country. The major focus of this research will then turn to an analysis of the three indicators in contemporary Taiwanese politics. The progress and shortcomings of human rights development across the three indicators will be studied under Chen Shui-bian’s term in office and then under that of Ma Ying-jeou. Although 1 Coomans, F., Grünfeld, F. and Kamminga, M.T. 2009. A Primer. In Coomans, F., Grünfeld, F. and Kamminga, M.T. (Eds). Methods of Human Rights Research. Antwerp: Intersentia. p. 12-13. 3.

(12) Chen’s time in office (two terms) was significantly longer than Ma, still in his first term, Chen was limited by an obstructive legislature while Ma has a KMT super majority. Nevertheless, this time difference will be taken into account and projections as to future developments will be considered.. 1.4. Overview of the three indicators Human rights are not a new concept. Earlier annunciations of human rights standards can be found in such famed documents as the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and the American Declaration of Independence. Overtime, more and more states considered it important to make reference to the principles of human rights in their constitutions. The events of World War II, however, resulted in. 政 治 大 international legal regime through the United Nations have vigorously pursued this. 立 Some states were quick to adopt and implement this newly internationalized concept,. an international effort to ensure the protection of human rights and from this time, the. ‧ 國. 學. while others ignored these international developments. As for Taiwan, Neary states: “Until 1987/88 merely to mention human rights was equivalent to criticizing the. ‧. government, practically the language of traitors, an attitude which has not completely disappeared.”2 Thus, in any study of human rights in Taiwan it is important to be. y. Nat. er. io. sit. aware of its historical background and political development.. al. v i n that must be met by governments. C h These universalUstandards – human rights – should e neach h i but this is often not the reality. The g cstate apply to all and protect the weakest in n. Under the international human rights regime, there exists a set of universal standards. international human rights standards, set out in the ICCPR, its protocols and the ICESCR require states to carry out implementation of the treaties and ensure protection of the human rights set out within those documents. National human rights bodies are an effective means of protecting these standards. Furthermore, considering the death penalty as an extreme denial of the fundamental right to life, efforts to abolish capital punishment are enshrined in the ICCPR and the Second Protocol.. 2. Neary, I. 2002. Human Rights in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. London: Routledge. p. 113. 4.

(13) 1.4.1. Implementing international human rights standards “The ICCPR is more than just a listing of rights” cites the American Bar Association. “The drafters – delegations of states’ representatives – agreed that a central obligation of the ICCPR would be the implementation of its provisions at the national level.”3 The present international system relies heavily on state enforcement of these principles. Some states have positively acted to ensure the protection of human rights in their jurisdictions while others, have not acted and continue to flaunt international law and violate their citizens’ human rights. Notwithstanding, Taiwan’s unique international status and exclusion from many international bodies, there are no limitations on the unilateral domestic implementation of international human rights standards. While historically, Taiwan’s record on human rights particularly under its. 政 治 大 democratic improvements in the last twenty years. Indeed, Chen states: “Many areas 立 of human rights law and practice have been reformed in Taiwan in the era of authoritarian regime was a blight, Taiwan’s isolation has arguably contributed to its. ‧ 國. 學. democratization, including criminal procedure, police powers, administrative procedure, and the freedoms of speech, assembly and association.”4 Therefore, it can. ‧. be seen that Taiwan has moved towards the promotion and protection of human rights within its borders in several areas, albeit in incremental steps and in the absence of. y. Nat. sit. comprehensive human rights policy prior to 2000. Although Lin considers Taiwan’s. al. er. io. non-recognition an incapacity to participate in the international system for the. n. protection of human rights, Taiwan is not domestically so limited and can unilaterally. Ch. implement international standards.5. engchi. i n U. v. 1.4.2. The importance of NHRCs Smith states: “[National Human Rights Institutions] play a crucial role in promoting and protecting human rights in a wide variety of ways.”6 She cites their abilities to monitor rights situations, handle complaints, audit laws, make recommendations to the government, train personnel and create public awareness as among their 3. Central European and Eurasian Law Initiative, 2003. ICCPR Legal Implementation Index. Washington: American Bar Association. p. 1 4 Chen, A.H.-Y. 2006. Conclusion: Comparative reflections on human rights in Asia. In Peerenboom, R., Petersen, C.J. and Chen, A.H.-Y. (Eds) Human Rights in Asia: A comparative legal study of twelve Asian jurisdictions, France and the USA. London: Routledge. p. 497 5 Lin, F.C.-C. 2006. The Implementation of Human Rights Law in Taiwan. In Peerenboom, R., Petersen, C.J. and Chen, A.H.-Y. (Eds) Human Rights in Asia: A comparative legal study of twelve Asian jurisdictions, France and the USA. London: Routledge. p. 315 6 Smith, A. 2006. The Unique Position of National Human Rights Institutions: A mixed blessing? Human Rights Quarterly, 28:4 904-946. p. 905. 5.

(14) noteworthy features. Furthermore, Smith points out their distinctive role in society, which she sees as a position in between government and civil society, independent of both and critical to their success.. International guidelines that outline a minimum set of standards for national human rights commissions (hereafter, NHRCs and also known as national human rights institutions NHRIs) have been agreed to by the United Nations. The ‘Paris Principles’ as they are known7 state that a mandate as broad as possible is desired. Specifically, NHRCs should possess the following capabilities: the capacity to monitor the domestic human rights situation, the duty to advise the government on human rights proposals and/or violations, powers to link with international human rights bodies and,. 治 政 the option of having quasi-judicial powers; however大 of these, Kjaerum states: 立 “Whereas an institution can hardly be recognized as fulfilling the Paris Principles if. a role to educate and inform the public of human rights obligations. There exists also. ‧ 國. 學. one of the first four elements is left out of its mandate, it is facultative to give it the mandate to hear and consider individual complaints and petitions.”8 Therefore, this. ‧. fifth power is technically optional, yet the Human Rights Commission states it is increasingly seen as the norm and preferred for NHRCs to possess this mandate as. Nat. sit. y. well.9 The Paris Principles set out comprehensive guidelines for country’s planning to. er. io. establish a NHRC. In 1990, only eight countries possessed such bodies but by 2002, this number has risen to 55.10. n. al. Mohamedou states:. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. “An NHRI has the possibility of effecting positive change. Even national institutions established for cosmetic purposes can transcend the limitations initially imposed upon them. This transformative effect on the broader society. 7. Approved by General Assembly Resolution 48/134 (20 December 1993) Kjaerum, M. 2003. National Human Rights Institutions Implementing Human Rights. Copenhagen: Danish Institute for Human Rights. p. 7 9 Declaration and Programme of Action. 2000. UN World Conference Against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance, paragraph 90 10 Kjaerum, M. 2003. p. 5 8. 6.

(15) is in fact vital to the inculcation and perpetuation of human rights awareness.”11. Given that NHRCs have such potential, they clearly have a valuable role to play. Such a role, though, is not secure without certain conditions being met. These include legitimacy, accessibility, networking ability and importantly, independence, factors which Mohamedou has examined extensively.12 Furthermore, Smith supports this argument and states: “These questions of independence go to the very heart of the debate about the effective functioning of a NHRI and highlight the difficulty for NHRIs in defining and protecting their space.”13 Particularly, in countries in periods of political change, those undergoing democratic transition and those trying to. 政 治 大. consolidate such reforms a NHRC can be a very effective tool.. 立. 1.4.3. International death penalty trends. ‧ 國. 學. Internationally, the situation of the death penalty and its continued use is one of decline. A majority of the world’s states have considered it necessary to prohibit its. ‧. use and it is considered possible that international opinion and pressure could eventually bring an end to executions throughout the world;14 however, this issue still. y. Nat. al. er. io. sit. sparks controversy and is by no means settled. Dieter states:. n. “Gradually, in the course of social evolution, a consensus forms among. Ch. i n U. v. nations and peoples that certain practices can no longer be tolerated. Ritual. engchi. human sacrifice is an example; slavery, too, has been largely abandoned; physical torture is widely condemned by most nations. Vestiges of these practices may continue, but those are aberrations that further underscore the fact that the world has turned against these practices.”15. Clearly, Dieter is an abolitionist but his view draws on a common conception that capital punishment is barbaric and antiquated and scholars draw on statistics that 11. Mohamedou, M.-M. 2000. The Effectiveness of National Human Rights Institutions. In Lindsnaes, B., Lindholt, L. and Yigen, K. (Eds) National Human Rights Institutions: Articles and Papers. Copenhagen: The Danish Centre for Human Rights. p. 58 12 Ibid. 13 Smith, 2006. p. 912 14 Dieter, R.C. 2002. The Death Penalty and Human Rights: U.S. Death Penalty and International Law. Oxford Roundtable. [Online] www.deathpenaltyinfo.org/Oxfordpaper.pdf [Accessed 7 May 2010] p. 1 15 Ibid.. 7.

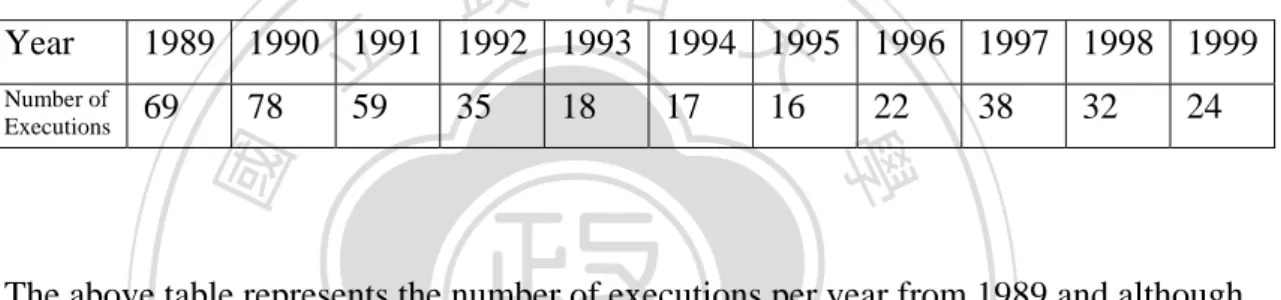

(16) indicate a movement away from the death penalty. Hoods states: “The average rate at which countries have abolished the death penalty has increased from 1.5 (1965-1988) to 4 per year (1989-1995), or nearly three times as many.”16 From 1989 to 1998, change in the number of abolitionist states was impressive. Dieter recalls that while in 1989 a mere 45 states had abolished capital punishment, that figure has risen to 88 in 1998 and when added to those de facto abolitionist at the time, it reached 110 states around the world.17 These statistics reveal a trend but fail to take into account three significant exceptions: the United States, Islamic countries and Asia. Johnson and Zimring state: “Asia should be important to students of capital punishment, therefore, for the same reason that Hawaii is of interest to volcanologists: because that is where the action is.”18. 治 政 大 is divided. The ICCPR does Under international law, the status of the death penalty 立 not categorically prohibit the death penalty. Article 6 protects against the arbitrary ‧ 國. 學. deprivation of life and does expressly ban the carrying out of executions on pregnant women and those whose crimes were committed under the age of 18. For countries,. ‧. which have not yet abolished the death penalty, the ICCPR restricts it to ‘the most serious of crimes’. Moreover, the ICCPR provides that the right to pardon or. Nat. sit. y. commutation of the death sentence must exist. 19 Significantly, the Second Optional. al. n. been as widely adopted as the ICCPR generally.. Ch. engchi. 16. er. io. Protocol to the ICCPR, which does unequivocally prohibit the death penalty, has not. i n U. v. Hood, R. 1996. The Death Penalty: A World-wide perspective. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8 Dieter, 2002. p.2 18 Johnson, D.T. and Zimring, F.E. 2006. Taking Capital Punishment Seriously. Asian Criminology, 1. 89-95, p. 91. 19 Art. 6 (1),(2),(4),(5) ICCPR 17. 8.

(17) 2. The Australian model of human rights development 2.1. Introduction In order to better understand Taiwan’s human rights position, an examination of human rights in a foreign setting will be undertaken. A good starting point to evaluate human rights (or any other standard for that matter) is to set a benchmark – a point of reference. Bearing this in mind, it is not the objective of this thesis to find a perfect human rights model and it is questionable as to whether one that can be applied to all situations even exists. Using Australia as a point of reference, we will be able to understand how human rights have been dealt with. Accordingly, Australia and its human rights development across the three indicators will be studied to provide an example.. 立. 2.1.1. Why Australia?. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Australia, a country with strong democratic traditions and commitment to the rule of law,1 protects human rights using various measures. Significantly, for the purposes of this thesis, it has ratified the international human rights treaties, established one of the. ‧. earliest national human rights institutions (NHRI) and has abolished capital. sit. y. Nat. punishment. Given that Australia has already addressed these issues over a significant period time and has shown a solid commitment, a study of Australia’s treatment of. io. n. al. er. these indicators will provide both useful and insightful guidance to measure Taiwan’s. i n U. v. progress. Besides population and economy, Australia and Taiwan may appear to have. Ch. engchi. little in common. Nevertheless, human rights cannot be looked at in a vacuum and, in terms of human rights regimes, I believe Australia is one of several that could be examined to highlight these issues.. Both countries are in the Asia-Pacific region, both countries have had strong links to the United States and both are committed democracies. Australia’s history as an immigrant country, its dealings with indigenous peoples and the human rights issues that have therein arisen can also be particularly useful for Taiwan. Various European. 1. Australia is recognized as one of the world’s longest continuing democracies. See further at: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2008. Australia’s System of Government. About Australia. [Online] www.dfat.gov.au/facts/sys_gov.html [Accessed 11 May 2010]. 9.

(18) states, seen by many as model human rights states,2 have much of their human rights protections in pan-European systems, which although very effective, an analysis of the European regime and its implementation is outside the scope of this research. Moreover, there is little chance of a regional-level human rights mechanism being established in Asia in which Taiwan could benefit from in the near future. The US has also been excluded for study, as the abolition of the death penalty has not yet been effected and its commitment to human rights across the other two indicators3 is questionable. It is, therefore, for these reasons and after this process of elimination has been carried out that Australia has been chosen from among the remaining countries suitable for comparison. Australia, with its lengthy experience in dealing with human rights across these three issues, is thus a suitable and interesting subject. 政 治 大. of comparison for this research.. 立. 2.2. Australia’s progress in the first indicator. ‧ 國. 學. The ICCPR and ICESCR form a major component of the so-called ‘International Bill of Rights’ – the bundle of documents that set out internationally recognized human. ‧. rights standards. Both Covenants were adopted by the United National General Assembly on 16 December 19664 and from this date became available for signature. y. Nat. sit. and ratification; however, it was to be another decade before both human rights. er. io. treaties were to come into force. Both documents have been ratified by Australia and. al. v i n Australia does not have any C bill of rights and this sets it aside from all other western hengchi U democracies, which have constitutional or statutory bills of rights. It does not follow, n. implemented to varying degrees. It is important to note, from the beginning, that. however, that Australia does not uphold human rights standards. Human rights in Australia are valued and, in the eyes of many Australians, for the most part well respected. Australians enjoy high living standards and have strong democratic institutions5 that enable a positive human rights environment, notwithstanding the lack of a bill of rights. In the absence of such, human rights are protected through a variety of means including a wide array of legislation both at federal and state levels. This section will examine how the ICCPR and ICESCR have been implemented in 2. European states are frequently rated highest. See Freedom House, 2010. Freedom in the World 2010 Survey [Online] www.freedomhouse.org [Accessed 5 April 2010]; Kekic, L, 2007. The Economic Intelligence Unit Index of Democracy. [Online] www.economist.com [Accessed 5 April 2010] 3 The US, although having signed the ICESCR, is not a party to it as it has not been ratified. 4 United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI) 5 In the 2009 UN HRI Index Australia ranks second and is frequently rated top 10 in democracy rankings.. 10.

(19) Australia, given that they have not been directly incorporated domestically into the Australian legal system and Australia does not have any other legal or constitutional enactment enunciating the assortment of human rights recognized in those documents.. 2.2.1. Ratification Under Australian law, treaties are not automatically incorporated into Australian law. Various attempts have been made to incorporate internationally recognized human rights (as found in the covenants) into Australian law. The first such attempt began with the signing of the human rights covenants. After two decades of conservative rule, the Australian Government of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam signed the ICCPR and ICESCR on 18 December 1972 within two weeks of coming to government and. 政 治 大 until the next government led by Malcolm Fraser of the Liberal Party came to power 立 in exceptional circumstances in November 1975. before even his full ministry had been decided. Neither of the treaties was ratified. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.2. The ICESCR. ‧. The ICESCR was ratified on 10 December 1975 arguably, as it was more aspirational in value and had less stringent requirements for implementation. At the time, the. y. Nat. sit. newly appointed government would have been wanting to ensure its legitimacy and. er. io. garner support following the dismissal of the socially reformist Whitlam government.. al. v i n prime minister’s commission for the first and only time to-date in Cand U h ethisnoccurred i h c g 1975. Although ratified, the ICESCR is not enforceable and is only the subject of n. In Australia, the governor-general under royal prerogative has the power to revoke a. reporting requirements by Australia. The Australian Human Rights Commission states: “The ICESCR does not, however, form part of Australia’s domestic law and is not scheduled to, or declared under, the AHRC Act.”6 The ICESCR, which mandates the ‘progressive realisation’ of economic, social and cultural rights, committed the government at the time to follow the spirit of the treaty and arguably appease the electorate. Successive governments have been bound by their commitments in areas such as education, health, and family matters and, Australia has been widely lauded for its progress in this regard. While not requiring the passage of legislation, the ICESCR mandates state action to achieve these aspirational rights. The same could 6. The Australian Human Rights Commission, 2010. The International Bill of Rights. Human Rights Explained, 5. [Online] http://www.hreoc.gov.au/education/hr_explained/5_international.html [Accessed 5 April 2010]. 11.

(20) not be said for the ICCPR, which requires States to take measures to respect the outlined rights and to provide individuals with ‘effective measures’ to enforce those rights. For this reason, the ICCPR and Australia’s efforts to implement it will be the main focus of this section on the domestic implementation of human rights standards.. 2.2.3. Direct implementation of the ICCPR The ICCPR was eventually ratified by Australia on 13 August 1980. Earlier attempts to implement (and ratify) the covenant had proved unsuccessful. In 1973, the previous Labor government of Whitlam had tried to pass legislation implementing the ICCPR. Federally, this was Australia’s first government attempt at implementing a legislative bill of rights, a debate that continues to this day. Whitlam’s Attorney-General, Lionel. 政 治 大 Senate debates, he argued: “Although we believe these rights to be basic to our 立 democratic society, they now receive remarkably little legal protection in Australia.”. Murphy introduced the Human Rights Bill into Parliament and argued its case. In. 7. ‧ 國. 學. His proposed law would have enshrined the rights contained in the ICCPR into a domestic statute and provided for a Human Rights Commissioner to investigate. ‧. infringements. This Bill, however, was never put to a final vote and lapsed before it could be passed.. sit. y. Nat. al. er. io. One year after ratification, implementation of the ICCPR was first effected with the. n. passage of the Human Rights Commission Act of 1981. Attaching the covenant as a. Ch. i n U. v. schedule to the Act and including a statement as to the desirability of federal laws to. engchi. conform to the ICCPR (among others), the Act established a human rights commission to examine laws to ensure conformity to human rights standards. This control was, however, not binding and mainly involved reporting inconsistencies of already passed laws. It also must be said that mere scheduling of a treaty does not domestically incorporate it into Australian law. Attaching the ICCPR as a schedule intended to provide guidance to those enforcing the Act but did not have any legal effect. Thus from 1981, the Australian Parliament had addressed the domestic implementation of the ICCPR albeit in a minimalist manner by using it as a ‘point of reference’ for the newly formed Human Rights Commission without direct legal effect. 7. Commonwealth of Australia, 1973. Australian Parliamentary Library Records [Online] http://www.aph.gov.au/library/intguide/law/rights19732ndR.htm [Accessed 10 April 2010]. 12.

(21) The next attempt to implement the ICCPR into Australia came in 1985. Bob Hawke’s Labor government had come to power and his Attorney-General Lionel Bowen introduced the Australian Bill of Rights Bill. This proposed law yet again attempted to implement the ICCPR by enshrining the human rights standards it contained in a bill of rights. This far-reaching law would have given human rights enforceability. Specifically, statutes that breached the bill of rights could be ruled inoperative to prevent inconsistencies. Furthermore, a revised and more powerful human rights commission was proposed that would have the power to hear individual complaints of infringements. The Bill was strongly opposed and was dropped as it was considered a major constraint on Australia’s Westminster form of government.. 治 政 大 in passing revised human The following year, the Hawke government succeeded 立 rights legislation. In 1986, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Act was passed ‧ 國. 學. and established the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission (HREOC). This set up the body that was proposed in the previous year’s bill; however, it did not. ‧. make binding ICCPR rights nor limit Parliament’s legislative authority. Similar to the 1981 Human Rights Commission Act, the 1986 Act attached the ICCPR as a schedule. y. Nat. sit. and defined human rights as to be those outlined in the international treaties. Those. al. er. io. rights could not be enforced through court action against others or the government;. n. however, it did allow the Commission to investigate human rights infringements and. Ch. i n U. v. to facilitate conciliation between parties as the only dispute resolution mechanism.. engchi. The legislation also provided for the commission to report its findings and conciliation results to the Attorney-General, giving further oversight to the government.. The 1986 Act has served as the basis for specific human rights protection at a federal level in Australia for over two decades and is assisted by various state antidiscrimination laws. As a federation, which divides legislative power between the states and Canberra, the states also have a significant role in human rights protection. Each state has adopted legislation protecting human rights and associated human rights commissions. Indeed, such state protections usually cover a wider range of rights and are more readily available to Australians. Two domestic jurisdictions have gone on to incorporate domestic bills of rights, notwithstanding a reluctance by 13.

(22) successive federal governments. The Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Victoria introduced the ACT Human Rights Act (2004) and the Victorian Charter of Rights and Responsibilities Act (2006) respectively. These two statutes, similar to the UK and Canadian human rights acts, enshrine human rights into domestic legislation and allow a court to issue a statement of incompatibility where it finds an act infringes human rights. They also provide for the enhanced scrutiny of legislation to ensure conformity to the outlined human rights standards. Therefore, we can see that human rights protections in Australia are covered to varying degrees at state and federal levels.. Without a bill of rights, Australia’s implementation of the ICCPR is unique. In areas. 治 政 大 is lacking. Although many rights are well protected. While in other areas, legislation 立 experts advocate a bill of rights for Australia, this is the subject of much debate and such as privacy and protection from racial, sexual, age and disability discrimination,. ‧ 國. 學. ongoing controversy. In 2008, the Federal Government commissioned a committee to conduct the National Human Rights Consultation and investigate community views. ‧. on human rights and their protection in Australia. The Consultation committee’s final report recommended the government introduce a bill of rights, among others and this. Nat. sit. y. generated much opposition.8 Australia prides itself on its democracy and system of. al. er. io. government. Indeed, human rights are fundamental to that system of government but. n. the enshrining of human rights protections binding on Parliament are considered a. Ch. i n U. v. limitation on popular sovereignty. Parliamentary supremacy is a cornerstone of the. engchi. Westminster system and a bill of rights is seen as shifting the power to regulate human rights away from elected representatives and into the hands of judges, who are appointed and unelected. It is within this context that the debate rages on the suitability of introducing a bill of rights in Australia. It is not generally a question of support for human rights but one of how best to protect them and who (whether the courts or legislature) should have the final say.. On 21 April 2010, the Australian Attorney-General announced changes to Australia’s human rights regime with important ramifications for the implementation of ICCPR in Australia. Significantly, the Rudd government refused to implement its 8. Commonwealth of Australia, 2009. National Human Rights Consultation. [Online] www.humanrightsconultation.gov.au [Accessed 10 April 2010]. 14.

(23) commissioned committee’s recommendations and legislate a bill of rights, recognizing the lack of consensus on the issue. The Framework, however, does outline increased protections for human rights should it become law. Significant changes proposed include legislating to establish a Joint Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights, which would be charged with scrutinizing bills to ensure compliance with international obligations. Furthermore, legislation is proposed which would require every new bill before Parliament to be accompanied by a statement of compatibility with the seven core UN human rights treaties to which Australia is a party.9 If the framework is implemented, its effect on Australia’s ICCPR compliance would be significant, bringing in a direct parliamentary role for the first time.. 政 治 大 Successive Australian governments have confirmed their support for human rights 立 and stress Australia’s compliance with international human rights instruments. 2.2.4. Indirect compliance. ‧ 國. 學. Australia, as a liberal democracy, ‘has a long tradition of supporting human rights around the world, and was closely involved in the development of the international. ‧. human rights system’10 and contends that human rights are protected under two different categories. In addition to the human rights mechanisms, Australia also. y. Nat. sit. contends that its system of law and the processes this liberal democratic tradition. al. er. io. provide, ensure in part compliance with human rights standards.11 These are referred. n. to as the ‘existing institutionalized processes’ in government reports and include the. Ch. i n U. v. protections inherently present in Australia’s system of government, which can be. engchi. considered indirect compliance. Australia’s democratic and parliamentary concepts of responsible government and committee scrutiny of legislation, constitutional guarantees (four express constitutional rights and several implied rights as recognized by the High Court) and the common law all uphold various civil and political rights. The judiciary and administrative law remedies provided though tribunals, under Freedom of Information requests and by Ombudsmen’s decisions also form part of this ‘existing institutionalized’ complementary in-built rights protections. Thus, Australia’s strong democratic traditions, commitment to the rule of law inherent in its. 9. Attorney-General’s Department, 2010. Australia’s Human Rights Framework. [Online] www.ag.gov.au/humanrightsframework [Accessed 21 April 2010] 10 Attorney-General’s Department, 2006. Common Core Document comprising Fifth ICCPR Report and Fourth ICESCR Report. [Online] www.ag.gov.au/humanrights [Accessed 21 April 2010] p. 10. 11 Ibid, p. 11. 15.

(24) system of law and government are often used, with or without justification, as a reason for the absence of comprehensive adoption of international human rights treaties into Australian law.. 2.2.5. Reporting and individual complaints The ICCPR was reinforced by Australia adopting the First Optional Protocol on 25 April 1991. It has been stated by the High Court of Australia that: “The opening up of international remedies to individuals pursuant to Australia’s accession to the Optional Protocol to the ICCPR brings to bear on the common law the powerful influence of the Covenant and the international standards it imports.”12 In addition, the individual complaints process has resulted in some important changes in Australian law. The. 政 治 大 concerned the illegality of homosexuality in his state. He contended this breached his 立 right to privacy under Article 17 and also Article 26 – the right to equality before the first successful complaint was by a Mr Toonen of Tasmania whose complaint. ‧ 國. 學. law and non-discrimination. The committee accepted this complaint and the federal government subsequently passed the Human Rights (Sexual Conduct) Act 1994. This. ‧. law successfully overruled the Tasmanian Criminal Code as confirmed by the High Court in Croome v. Tasmania.. sit. y. Nat. al. er. io. Unfortunately, however, the Australian government has not always responded so. n. positively to the UN Human Rights Committee’s rulings. Various complaints that the. Ch. i n U. v. Committee has found Australia to be in breach of its obligations have been rebutted. engchi. and ignored especially in immigration cases. Without an effective means of enforcement, this complaint system cannot be seen as a firm guarantee but does highlight issues and put the government on notice to at least justify its conduct. Similarly, the reporting requirements that the ICCPR provides in Article 40 also provide means for further scrutiny of Australia’s human rights record and conformity to its international obligations. However, in practice, criticism has surrounded this process. Australia has been criticized for filing late and minimalist, website ‘cut and paste’ style reports.13. 12. Mabo v State of Queensland (1992) 175 CLR 1, at 42, per Brennan J (Mason and McHugh JJ concurring) Celermajer, D. 1996. Overdue and Understated: Australia’s draft third ICCPR report. Human Rights Defender, 22. 13. 16.

(25) 2.2.6. Concluding remarks on the ICCPR in Australia Although ratified, due to the nature of the Australian legal system, the ICCPR in its entirety is not strictly enforceable in Australia in the absence of enabling legislation. Legislation safeguards various rights and other protections are in place but to date, a comprehensive domestic incorporation of the ICCPR has not been effected. Instead a piecemeal approach exists, where the level of protection depends on specific rights. For the large part though, many Australians are proud of their political system and its inherent safeguards to human rights, which clearly make Australia a unique human rights state.. 2.3. The second indicator – Australia’s national human rights institutions. 政 治 大 Australia has been at the forefront of NHRC development. 立 2.3.1. Establishment of NHRCs. 14. Australia’s commitment. to human rights has been evidenced through the establishment of various human. ‧ 國. 學. rights bodies and their development has gone hand and hand with Australia’s attempts to implement international human rights standards, though the former has been more. ‧. successful. The first human rights commission was formed in 1981 and five years. y. Nat. later, the current body, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission. sit. [HREOC] (now renamed the Australian Human Rights Commission [AHRC]) came. er. io. into being. While the first commission had a limited role and was merely a part-time. al. n. v i n C h under section 9(1) inconsistencies to the Government e n g c h i U Human Rights Commission Act of 1981. Like the majority of national human rights institutions, the Australian body, it did enable commissioners to investigate and report human rights. HREOC was established by an act of parliament. The Paris Principles support giving such bodies wide-ranging scope and reinforce that such a mandate should have constitutional or legislative force. In the case of Australia, with rigid procedures in place, which minimize amendments to the constitution, the Hawke government in 1986 passed the Human Rights and Equal Opportunities Commission Act and provided for a new body with increased powers. The institutional framework of the. 14. Lindsnaes, B. and Lindholt, L. 2000. National Human Rights Institutions: Standard-setting and achievements. In Lindsnaes, B., Lindholt, L. and Yigen, K. (Eds) National Human Rights Institutions: Articles and Papers. Copenhagen: The Danish Centre for Human Rights. p. 13. 17.

(26) current Australian Commission has been commended ‘as a model and source of inspiration for the development of the Paris Principles’.15. 2.3.2. Composition of the NHRC The Australian Human Rights Commission is composed of members known as commissioners and along with its president, is based in Sydney. Although the government of the day appoints its members, commissioners are appointed on their expertise, not political considerations, and are required to act independently. Pluralistic in nature, specific commissioners are appointed to various positions including Sex Commissioner, Race Commissioner and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commissioner and focus their efforts on preventing discrimination in those. 政 治 大 added to the commissioners’ duties. Currently, there are four people who occupy the 立 various positions and as such, serve dual mandates. For example, the president is vulnerable areas. Later, roles in age discrimination and disability rights have been 16. ‧ 國. 學. both president and human rights commissioner and the sex discrimination commissioner also has responsibility for age discrimination. In late 1990s, the. ‧. HROEC had a staff of around 100 but such numbers can be prone to budgetary fluctuations.17. sit. y. Nat. er. io. 2.3.3. Powers and duties. al. v i n disability discrimination promotes disputes. Since findings are C h conciliation to solve U i e h n must g c consent to any resolution, ARHC not legally binding and as both parties n. The AHRC can hear individual complaints and in cases of race, sexual, age and. complaints that are terminated or do not result in satisfactory outcomes may require proceedings in the federal courts and this is available under section 46PO.18 Previously, the former HREOC served as a quasi-judicial body and had powers of enforcement but these were ruled invalid by the High Court in Brandy v HREOC.19 In addition to the conciliation of complaints, the AHRC can also intervene in court proceedings as an amicus curiae or friend of the court.. 15. Ibid, p. 46 Australian Human Rights Commission, 2010. About the Commission. [Online] www.hreoc.gov.au [Accessed 11 May 2010] 17 Lindsnaes and Lindholt, 2000. p. 23 18 Australian Human Rights Commission Act (Cth) 1986 19 High Court of Australia. [1995] HCA 10. 16. 18.

(27) Further powers are available to the AHRC, which go beyond the role of dispute resolution and with its conciliation mechanisms are the major functions of the commission. With a focus on non-discrimination, equal opportunities (especially in employment) and vulnerable groups, the AHRC is not just a complaints-based institution but one which also conducts education, information and promotional activities.20 Lindsnaer and Lindholt state that somewhat unique among NHRCs is the AHRC’s rich focus on conducting public inquiries and extensive research into the rights of vulnerable groups21 and this is evidenced by such reports as the same-sex couples rights report of 2007 and many indigenous rights surveys.22. 2.3.4. State and Territory NHRCs. 政 治 大 territory has its own human rights commission to protect human rights on a state basis. 立 The state commissions generally have wider roles than the AHRC given Australia’s Furthermore, in addition to the NHRC that exists on a federal level, each state and. ‧ 國. 學. constitutional framework. As stated above, the legislative powers of the Commonwealth (federal) Parliament are provided for under the specific constitutional. ‧. heads of powers with residual powers remaining with the states.23 Therefore, there are various areas in which the federal government has no basis to legislate and as such,. y. Nat. sit. human rights legislation at a federal level has been dealt with under the foreign affairs. al. er. io. power24 (as human rights derived from a treaty are so considered). Without such. n. foundations in an international agreement, the federal government must rely on the. Ch. i n U. v. states to legislate and it is for this reason, and arguably the different political. engchi. orientation of the various state governments that human rights protections under state laws are often more broad and comprehensive. For example, the Queensland AntiDiscrimination Commission can hear a wider range of complaints such as those for discrimination on the grounds of gender identity and, political and religious activity.25. 20. Section 11A(g)(h)(j), Australian Human Rights Commission Act (Cth) 1986 Lindsnaes and Lindholt, 2000. 22 Australian Human Rights Commission, 2010. Human Rights Publications. [Online] http://www.hreoc.gov.au/human_rights/publications.html [Accessed 11 May 2010] 23 Sections 51 and 52, Australian Constitution. 24 Section 51 (xxix) 25 Section 7, Anti-Discrimination Act 1991 (Qld) 21. 19.

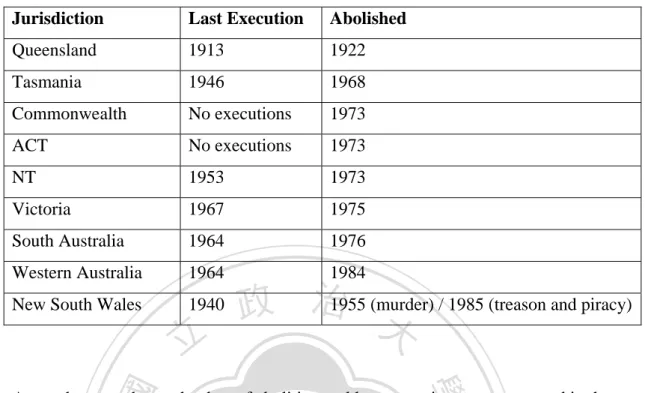

(28) 2.3.5. Assessment of Australia’s NHRCs Overall, Australia’s introduction of NHRCs has been very successful. There exists a major federal body and corollary state or territory commissions with powers to hear complaints and conduct education, promotion and awareness. Although such bodies do not have binding decision-making powers, as this would impinge of the separation of powers under the Australian Constitution, where complaints cannot be resolved through conciliation, an alternative route to resolution is available through the courts. The commissions are well served by their independent and professional commissioners and especially, with regards to their functions in the areas of human rights promotion and community awareness; NHRCs in Australia fulfill a vital role in Australia’s human rights framework.. 治 政 2.4. The third indicator – death penalty in Australia 大 立 2.4.1. Abolition in Australia ‧ 國. 學. The abolition of the death penalty in Australia has been effected gradually since 1922. As criminal law is generally under state, not federal, jurisdiction in Australia, formal. ‧. abolition was not uniformly introduced across Australia. Queensland was the first state to abolish the death penalty in 1922 and its last execution took place in 1913. For. y. Nat. sit. the offence of murder, the last state to formally repeal capital punishment was. al. er. io. Western Australia in 1984 and in 1985, New South Wales legislated against the. n. possible death penalty that still existed for the crimes of treason and piracy, becoming. Ch. i n U. v. the last state to remove the death penalty from its law books, although executions had. engchi. not occurred in those states since 1964 and 1940 respectively. The last execution carried out in Australia was in Victoria in 1967 and is still the subject of much debate. At a federal level, the Death Penalty Abolition Act of 1973 abolished capital punishment for federal crimes, notwithstanding executions had not ever been carried out federally.. 20.

(29) Table 2. Death Penalty Abolition in Australia26. Jurisdiction. Last Execution. Abolished. Queensland. 1913. 1922. Tasmania. 1946. 1968. Commonwealth. No executions. 1973. ACT. No executions. 1973. NT. 1953. 1973. Victoria. 1967. 1975. South Australia. 1964. 1976. Western Australia. 1964. 1984. New South Wales. 1940. 立. / 1985 (treason and piracy) 政 治1955 (murder) 大. ‧ 國. 學. As can be seen above, the date of abolition and last execution never occurred in the same year. There was usually a period of around ten to twenty years between the last. ‧. execution and formal abolition in each jurisdiction. A period of de facto moratorium. y. Nat. was used and in Australia’s case, this meant the sentences of those sentenced to death. er. io. mercy.. sit. were commuted to life imprisonment by the government under the prerogative of. al. n. v i n C h– opposition confirmed 2.4.2. Recent Developments engchi U. Further significant developments post-abolition include accession to the Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR27 on 5 October 1990 and the recent passage of federal legislation. Early in 2010, the federal government approved Crimes Legislation Amendment (Torture Prohibition and Death Penalty Abolition) Act, which has reinforced Australia’s opposition to the death penalty and prevents the states from reintroducing the death penalty. On the international stage too, Australia has also shown its support for the worldwide abolition of the death penalty. In 2007, Australia was a sponsor and supporter of a significant United Nations General Assembly. 26. Brynes, A. 2007. The Right to Life, the Death Penalty and Human Rights Law: An international and Australian perspective. UNSW Faculty of Law Research Series, 66. 27 Walton, M. 2005. Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR. NSW Council of Civil Liberties Background Paper, 4.. 21.

(30) resolution opposing the death penalty. The resolution sought an immediate moratorium on executions as a preliminary effort to end capital punishment globally.28 Furthermore, Australia co-sponsored a resolution ‘On the Question of the Death Penalty’ before the Human Rights Council in 2005 and refuses to extradite defendants to jurisdictions in which they may be subject to capital punishment without guarantees to the contrary, as a matter of policy.. 2.4.3. Public opinion on the death penalty Although abolition has been effected, it is interesting to explore public opinion on this issue in Australia. Potas and Walker state: “Whenever a particularly vicious crime is committed, members of the public, police, politicians and the press ‘re-open’ the. 政 治 大 Indeed, the response to the Port Arthur Massacre in 1996, in which 36 people were 立 murdered by a single gunmen in Australia’s worst ever killing spree, was not to debate on the death penalty.”29 However, such populism has not been acted upon.. ‧ 國. 學. reintroduce capital punishment but to tighten gun control laws30, notwithstanding calls for the mass-murderer’s death.. ‧. It is significant to note that the death penalty retained widespread public support at the. y. Nat. sit. time of its abolition and indeed, in the preceding years in which executions were. al. er. io. commuted in most Australian jurisdictions. Statistics reveal that support for the death. n. penalty in Australia was relatively strong: 67% in 1947, 68% in 1953 and 53% in. Ch. i n U. v. 1962.31 At these times, executions had already been abolished in one state and. engchi. moratoriums had begun in others. During the 1970s and 1980s, figures of around 40 percent were still in favour of the death penalty; however, these statistics come from a survey that also makes available the option of life imprisonment, which recorded around an equal number.32 Undoubtedly, questionnaires without this option, merely a direct yes or no question would reveal higher support. Support for the death penalty. 28. Law Council of Australia, 2010. Death Penalty Background. [Online] http://www.lawcouncil.asn.au/programs/criminal-law-human-rights/death-penalty/death-penalty_home.cfm [Accessed 29 April 2010] 29 Potas, I. and Walker, J. 1987. Capital Punishment. Issues and Trends in Crime and Criminal Justice, 3. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology. p. 2 30 McPhedran, S. and Baker, J. 2008. The Impact of Australia’s 1996 Firearms Legislation: a research review with emphasis on data selection, methodological issues, and statistical outcomes. Justice Policy Journal, 5:1. 31 Roy Morgan Research, 2009. Australians say penalty for murder should be Imprisonment (64%) rather than the Death Penalty (23%). [Online] http://www.roymorgan.com/news/polls/2009/4411/ [Accessed 17 June 2010] 32 Ibid. 22.

(31) spiked in the early 1990s with over half of Australians preferring capital punishment, yet by this stage abolition had been affected. Furthermore, Williams cites statistics, which reveal a majority of Australians still support the death penalty as of 2006 and that 44 per cent support its reintroduction as of 2007.33 This shows that the issue of the death penalty in Australia has not been dominated by opinion polls. While there was support for its abolition, at the same time there was strong opposition as well. In spite of calls for its reintroduction and polls in its favour, major political parties in Australia support the current position and reject such populist calls when they arise.. 2.5. Overview of Australia’s human rights The Australian example demonstrates that human rights issues are not static. The. 政 治 大. process of implementing human rights standards and protections has been an on-going process for over 40 years and continues to this day. Australia has been a leader in. 立. human rights across various indicators, notably as one of the first countries to. ‧ 國. 學. establish a NHRC and as the first country to formulate a national action plan. In Australia’s experience, it can be pointed out that human rights developments have. ‧. occurred across the political spectrum and no one party has dominated the issue. Progress has taken time and frequently, policy and proposed legislation have not been. Nat. sit. y. implemented. Continued effort has been required. Bipartisan support for human rights. io. er. has been instrumental given the very incremental nature of development in this area. Although at times, one side has favored issues the other opposed, the key point is that. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. human rights protections have not been weakened upon changes in government. This. engchi. acceptance has greatly contributed to human rights progress in Australia.. Australian efforts in and commitment to human rights are particularly evident in its strong institutional framework and its position on the death penalty. The Australian Human Rights Commission and corollary bodies in each state and territory are often seen as exemplars in their field. In its opposition to the death penalty, Australia’s commitment is steadfast even in the face of public opposition.. Although such progress is commendable, Australia provides us with an illustration of the difficulties in implementing international human rights standards, which can be useful to other countries in the process of or considering such implementation. 33. Williams, G. 2010. No Death Penalty, No Shades of Grey. The Sydney Morning Herald, 2 March.. 23.

(32) Australia’s piecemeal approach to implementing international human rights standards, while comprehensive, is not ideal. The absence of a bill of rights or equivalent and the ongoing opposition to one are remarkable. Fortunately, however, as a signatory to the first optional protocol to the ICCPR, the individual complaints process has served as a protection of last resort alleviating in parts the lack of direct enforcement of international human rights treaties. As has been witnessed in the latest efforts to introduce a bill of rights, although again unsuccessful, Australian human rights protections have been lifted in the process. The commitment to human rights is not black and white. Although methods on how best to uphold human rights in Australia are debated, across the board, Australians support human rights but leadership is required to effect change. Pandering to ‘division in the community’, the Australian. 治 政 大are met and in the case of both Conviction is needed to ensure international standards 立 Australia and Taiwan, this is no easy task. Government has reneged on its principle and backed away from a bill of rights.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 24. i n U. v.

數據

相關文件

Now, nearly all of the current flows through wire S since it has a much lower resistance than the light bulb. The light bulb does not glow because the current flowing through it

If a contributor is actively seeking an appointment in the aided school sector but has not yet obtained an appointment as a regular teacher in a grant/subsidized school, or he

It is intended in this project to integrate the similar curricula in the Architecture and Construction Engineering departments to better yet simpler ones and to create also a new

double-slit experiment is a phenomenon which is impossible, absolutely impossible to explain in any classical way, and.. which has in it the heart of quantum mechanics -

• Contact with both parents is generally said to be the right of the child, as opposed to the right of the parent. • In other words the child has the right to see and to have a

Menou, M.著(2002)。《在國家資訊通訊技術政策中的資訊素養:遺漏的層 面,資訊文化》 (Information Literacy in National Information and Communications Technology (ICT)

The point should then be made that such a survey is inadequate to make general statements about the school (or even young people in Hong Kong) as the sample is not large enough

To look at the most appropriate ways in which we should communicate with a person who has Autism and make it.. applicable into our day to