Syllable-Final Nasal Mergers in Taiwan Mandarin—

Leveled but Puzzling

Hui-ju Hsu

Chung-yuan Christian University

John Kwock-ping Tse

Providence University

The current study examines syllable-final nasal mergers in Taiwan Mandarin. One major finding is that the ethnic gap of syllable-final nasal mergers has been leveled. Meanwhile, the merger directions observed in the current study are in accordance with Ing (1985) and Chen (1991a) in that the syllable-final nasals tend to be alveolarized if preceded by [ə] and velarized if preceded by [i]. However, this [iN] merger direction contradicts Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992). Chen (1991a) and the current study presented inconsistent results in terms of the leading merger. Chen (1991a) suggested that [in] to [iŋ] was leading the merger while the current study suggests that the leading merger is [əŋ] to [ən].

Key words: Taiwan Mandarin, leveling, syllable-final nasal merger 1. Introduction

Mandarin has two syllable final nasals, [n] and [ŋ]. In Taiwan Mandarin, these two sounds seem to perform in an unstable manner. Mergers of one to the other have been observed in previous studies, such as Kubler (1985), Ing (1985), Chen (1991a), and Tse (1992). However, these studies, though published nearly contemporarily, did not reach an agreement regarding the merger directions; some even further linked the mergers to the stigmatized Taiwanese Mandarin (e.g. Kubler 1985). The current study, aided by acoustic analysis, aims to reexamine the puzzle of syllable-final nasal merger in Taiwan Mandarin. 2. Terminology

In order to avoid confusion or misunderstanding, the current study defines four terms as follows.

2.1 Taiwanese Mandarin

Taiwanese Mandarin refers to the Southern-Min accented Mandarin, mainly because Southern Min has the largest population among the language groups in Taiwan; the people as well as the language of Southern Min are thus generally named Taiwanese. It is noteworthy that equalizing Southern Min with Taiwanese has been recently criticized as one type of Southern Min chauvinism; the overgeneralization of Southern Min to Taiwanese in

Taiwan is gradually waning.

Taiwanese Mandarin is phonologically affected by Southern Min in many aspects. Since the speakers of Taiwanese Mandarin acquire Mandarin as a second language and usually speak it only when speaking to non-Southern-Min speakers, Southern Min still acts as the daily language they can most comfortably manage. These people are relatively aged in the population of Taiwan. In general, Taiwanese Mandarin is a stigmatized variety of Mandarin because “Standard Mandarin” had been exclusively promoted for decades in the education system, as well as the mass media. Cheng (1997:39) analogized Taiwanese Mandarin1 with

ebonics in that both maintained unique structures and systems, but were stigmatized and not officially recognized.

2.2 Taiwan Mandarin

Taiwan Mandarin, like Taiwanese Mandarin, also refers to a variety of Mandarin spoken in Taiwan. The differences between these two varieties lie in the phonological features and the statuses. As described above, Taiwanese Mandarin is stigmatized, but Taiwan Mandarin is not. In the current study, Taiwan Mandarin refers to the standard Mandarin natively spoken by people in Taiwan, particularly young people. The Southern Min features that stigmatized Taiwanese Mandarin are in general no longer observed in Taiwan Mandarin. It is noteworthy that Taiwan Mandarin, due to its constant contact with local languages in Taiwan, remains distinct from the Mandarin spoken in China, and has developed its own stable linguistic system. The speakers of Taiwan Mandarin are generally bilinguals of Taiwan Mandarin and (one of) their parents’ first language(s), but with better capability of Mandarin. Some younger speakers are even Mandarin monolinguals. The ethnicity of Taiwan Mandarin speakers can hardly be recognized via their Mandarin accents.

Guoyu, literally meaning ‘national language’, refers to the Standard Mandarin taught at

schools in Taiwan. It was mainly modeled after Beijing Mandarin, especially at the phonological level, but with some modifications. However, the idealized Beijing Mandarin “standard” has never pervaded Taiwan. This is probably because of the constant contact between Mandarin and Taiwan local languages, and the relatively small number of native Beijing Mandarin speakers among the Mandarin promoters in Taiwan (Cheng 1985). In the current study, Taiwan Mandarin is used synonymously with Guoyu.

2.3 Benshengren

The ethnic groups in Taiwan can be broadly categorized into four groups. They are

1 Though Cheng (1997) adopted the term “Taiwan Mandarin”, the features discussed in that study are more

Southern Min, Hakka, Mainlander, and Aborigine. As Southern Min has the largest population among these four groups, Southern Min people are usually overgeneralized as Taiwanese, or Benshengren, literally meaning ‘the people of this province’ with “this province” referring to Taiwan. They are the descendents of the Chinese immigrants from Southern Min dialect areas of Fujian (also named Min) Province during the period of the late 16th to the late 19th century. Southern Min is the major language of Benshengren, particularly the older generation.

2.4 Waishengren

Waishengren, literally meaning ‘the people from other provinces’, refers to Mainlanders,

or the Chinese immigrants to Taiwan after World War II and their descendents. The first generation of Waishengren are from various dialect areas in China. In other words, Standard Mandarin, the language that had been promoted in China since the early 20th century, is not the first language of most of the first generation of Waishengren.

Politically and communicatively, Mandarin, the national language promoted by a national government policy in Taiwan, has been associated with Waishengren. The large-scale immigration of Waishengren to Taiwan was politically activated, and a large number of first generation Waishengren then started to work for the government, in schools, the military, or other governmental institutes. Politically, Waishengren thus generally adopted Mandarin as their language. Communicatively, although most first generation

Waishengren are not native speakers of Beijing Mandarin, the closest Mandarin dialect to

Standard Mandarin, many of them are native speakers of various dialects of Mandarin. Mandarin, in a broad sense, naturally became the lingua franca among Waishengren. Contrastively, the local languages in Taiwan, mainly southern Chinese languages, are geographically and etymologically more distant to Standard Mandarin. Thus, in terms of political and linguistic aspects, Waishengren are generally associated with Mandarin. In other words, the linguistic background of Waishengren has been overgeneralized and they are thus regarded as speakers of Standard Mandarin, the code promoted by the government.

It is noteworthy that since the term Waishengren carries the modifier wai, literally meaning ‘outside’, implying exclusivity and alienation, some friendly new terms have been coined recently to refer to Waishengren, such as 新 移 民 (xin1yi2min2 ‘the new immigrants’) and 新住民 (xin1zhu4min2 ‘the new residents’). The current study uses the term Waishengren instead of such new terms because they are, comparatively, not as widely used as Waishengren. Furthermore, the ethnic standoff between Benshengren and

Waishengren has been reduced to nearly inexistent among the people of Taiwan. It is

believed that most people in Taiwan simply neutrally use these two terms as proper nouns when ethnicity is referred to; no exclusivity and alienation are implied.

3. Previous studies

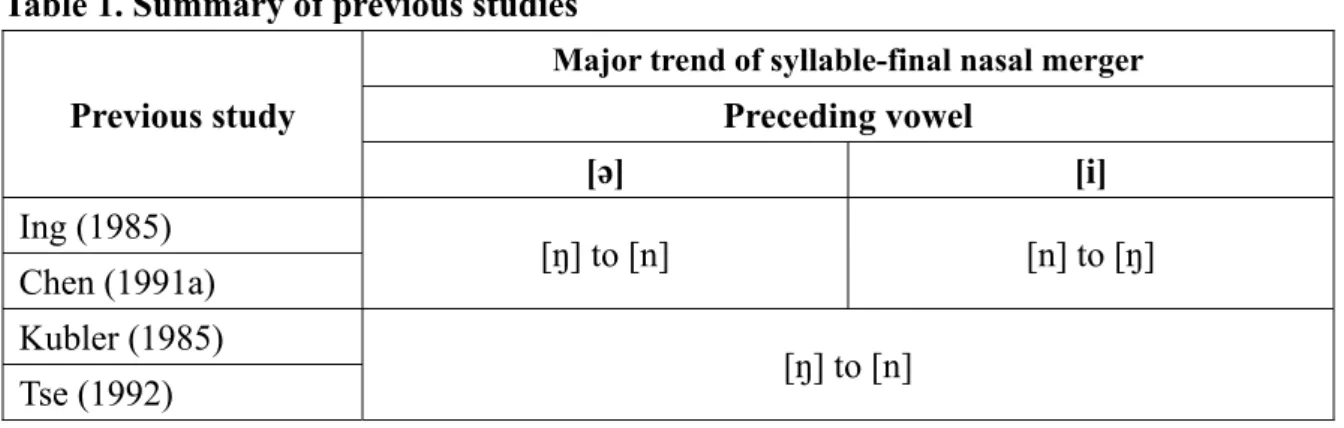

Previous studies of syllable-final nasal mergers in the Mandarin in Taiwan are bifurcated in terms of their results of the merger direction of [iN]. The merger direction of [əN] indicated in previous studies concurred; the mergers of [aN] were rarely reported.

Both Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992) agreed that alveolarization was the predominant trend of Taiwan Mandarin syllable-final nasal merger. Kubler reported that the non-standard Taiwanese Mandarin speakers often replaced [əŋ] and [iŋ] by [ən] and [in] respectively. Tse (1992) also reported a trend of the [əŋ]/[iŋ] to [ən]/[in] merger to various degrees. Ing (1985) and Chen (1991a), however, merely partially corresponded to Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992). In his discussion of the trends and errors of Mandarin pronunciation in Taiwan, Ing (1985), as Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992), reported the merger of [əŋ] to [ən] as well; he further described this merger as a widespread Mandarin “error” in Taiwan (p.419). However, Ing suggested a different observation of the [iN] variable in that [in] to [iŋ] was the major trend, although the merger of [iŋ] to [in] remained observable. Chen (1991a) analyzed the sound data of 60 Taiwan Mandarin speakers with nearly equal numbers of

Waishengren and Benshengren, ranging in age from 19 to 49. The study showed similar

results to Ing (1985) in that syllable-final nasal alveolarization was predominant when the nasal was preceded by [ə]. In the environment of [iN], the nasal tends to be velarized. Table 1 summarizes the results of previous studies on Mandarin syllable-final nasal merger.

Table 1. Summary of previous studies Previous study

Major trend of syllable-final nasal merger

Preceding vowel [ə] [i] Ing (1985) [ŋ] to [n] [n] to [ŋ] Chen (1991a) Kubler (1985) [ŋ] to [n] Tse (1992) 4. Research questions

The current study aims to investigate two issues. The first is to respond to one of Kubler’s (1985) arguments that syllable final nasal mergers were performed in Taiwanese Mandarin, a stigmatized variety of Mandarin in Taiwan, but not in standard Taiwan Mandarin. The current study, more than 20 years after Kubler’s, plans to examine whether these mergers remain stigmatized, and, if they do, in what manner do they remain stigmatized. The second issue is to respond to the inconsistent results of previous studies

regarding the directions of the syllable-final nasal mergers. Do the two nasal mergers proceed in the same direction of [əŋ]/[iŋ] to [ən]/[in] as Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992) suggested, in two opposite directions depending on the preceding vowels as Ing (1985) and Chen (1991a) stated, or perhaps even in another manner?

5. Methodology 5.1 Subjects

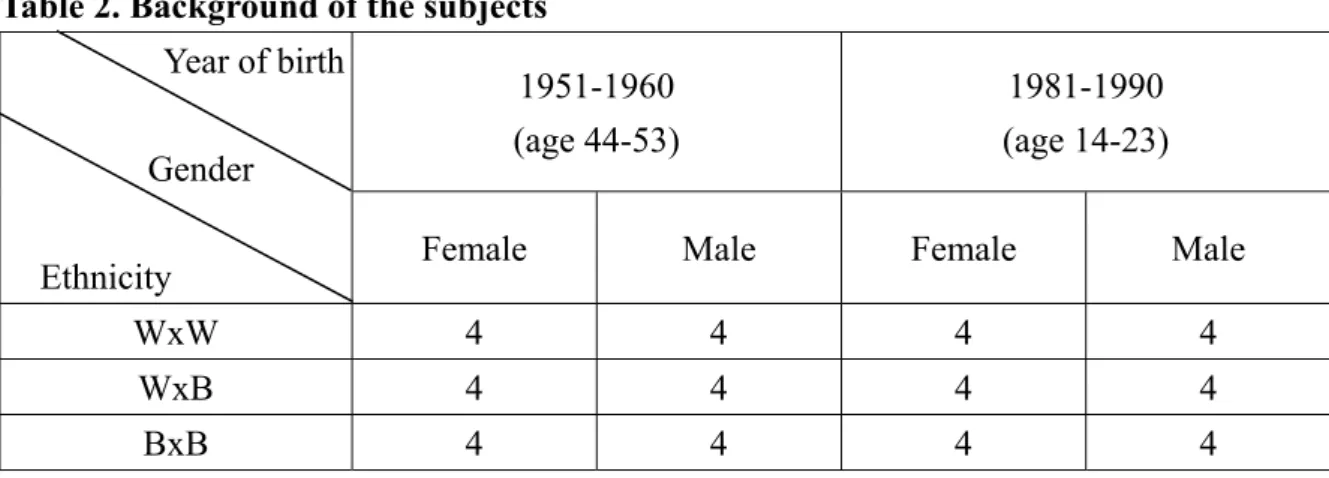

Forty-eight subjects were recruited for this study. All subjects were born and raised in metro Taipei (henceforth Taipei), including Taipei City (the capital of Taiwan) and Taipei County, the most populated county in Taiwan. The subjects must have/had resided in Taipei from the age of 3 to at least 18—if applicable, as two subjects were under the age of 18. As to the educational background, the subjects older than 18 in this study were all college-educated or higher.

The regional restriction on Taipei was to maximize the subjects’ Taiwan Mandarin nativity. Mandarin has been the only official language allowed in the government, and Taipei has been the political center of Taiwan. Taipei thus has been considered the “center” of Taiwan Mandarin. Demographically, Waishengren in Taipei account for a large portion of this population (Li 1970), having made Taipei more Mandarin-friendly than the rest of Taiwan. This image of Taipei as the center of Mandarin in Taiwan was also applied in some previous linguistic studies. In Chen (1991a), Taipei subjects were adopted as the representative speakers of Taiwan Mandarin. Ang (1992) even named the Mandarin spoken in Taiwan as “Taipei Mandarin”. Huang (1993:246) investigated the language usage in families where intermarriage was present and suggested that Mandarin was predominant in Taipei.

All 48 subjects in the current study were equally subcategorized by gender, two generations, and three ethnicities (Table 2). Each cell in Table 2 thus contains four subjects. The two generations were decided according to the subjects’ year of birth—(1) 1951-1960 (henceforth the older group), and (2) 1981-1990 (henceforth the younger group).

The current study considers those who were born in the year 1951, including

Waishengren, the first generation that learned Mandarin natively in Taiwan. This is because

the Taiwan government initiated the full-scale “Speak Mandarin Movement” in 1956 (Tsao 1997:51), designating Mandarin as the only language allowed in the government, schools and on public occasions. The elementary school education of those born in 1951 started nearly immediately after the initiation of this exclusive Mandarin policy. In the four-generation family investigated in Hsu (1998), the subjects born after 1951 adopted Mandarin more frequently, implying the effect of this language policy on education. The

younger group subjects in the current study, on the other hand, were selected to represent the first descendent generation of the older generation.

The ethnicities of the subjects were subcategorized according to the degree of cross-ethnic intermarriage. Three subcategories were proposed:

(1) a. Waishengren x Waishengren (henceforth WxW): Both parents are Waishengren. b. Waishengren x Benshengren (henceforth WxB): The father is Waishengren and the

mother is Benshengren.2

c. Benshengren x Benshengren (henceforth BxB): Both parents are Benshengren. All subjects, except the BxB older group, were, on a self-reported basis, native Mandarin speakers. In general, the BxB older subjects speak Southern Min as their first language. However, they can manage Mandarin (nearly) natively as it has been the only language used in the education system since 1951, and is the dominant language in the public domain.

Table 2. Background of the subjects Year of birth Gender Ethnicity 1951-1960 (age 44-53) 1981-1990 (age 14-23)

Female Male Female Male WxW 4 4 4 4

WxB 4 4 4 4 BxB 4 4 4 4 5.2 Equipment

An Olympus portable digital recorder (Olympus DS-10) was used to record the voice data.

5.3 Stimuli

Both of the two Mandarin syllable final nasals—[n] and [ŋ]—can be preceded by the following three vowels—[a], [i], and [ə]. The 10 most frequent syllables ending with each of the six vowel+nasal combinations, i.e. [an], [aŋ], [in], [iŋ], [ən], [əŋ], were selected as the stimuli. The frequencies of the stimuli syllables were based on the technical report

Mandarin Chinese Character Frequency List Based on National Phonetic Alphabets (henceforth, Chinese Character Frequency List) published by the Chinese Knowledge Information Processing Group (CKIP), Academia Sinica. Furthermore, in order to elicit the speech to the highest possible degree of naturalness, these highly frequent syllables selected from Chinese Character Frequency List were further adopted to search in the Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese (Sinica Corpus) for the most frequent bi-syllabic terms with the stimuli being placed at the second syllable.

These carrier terms were furthered carried in sentences. Each carrier sentence contained eight or nine syllables. To minimize the effect of coarticulation, the stimulus was placed on the second syllable of the carrier term, which was further placed at the final position of the carrier sentence. For instance, the most frequent syllable ending with [in] reported in the Chinese Character Frequency List is 品 (pin3 ‘an item’), and the most frequent bi-syllabic term ending with pin3 in the Sinica Corpus is 作品 (zuo4pin3 ‘works’), thus zuo4pin3 was the carrier term. The carrier term was further placed at the final position of the carrier sentence. (2) presents one example of a carrier sentence. Figure 13 illustrates the selection

of stimuli and the formation of carrier terms and carrier sentences.

(2) Zhe4 shi4 yi2bu4 you1xiu4 de0 zuo4pin3. this is one.CLASSIFIER excellence ADJ work ‘This is an excellent work (of art, etc.).’

Figure 1. An example of the formation of the carrier sentence 5.4 Procedure

A sentence list containing the 60 carrier sentences of the syllable-final nasals and the carrier sentences of other variables was presented to the subjects. The subjects were

3 For the complete list of stimuli and their carrier terms/sentences, please see Appendix.

[-in]

Mandarin Chinese Character Frequency List Based on National

Phonetic Alphabets pin3

Academia Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese zuo4pin3

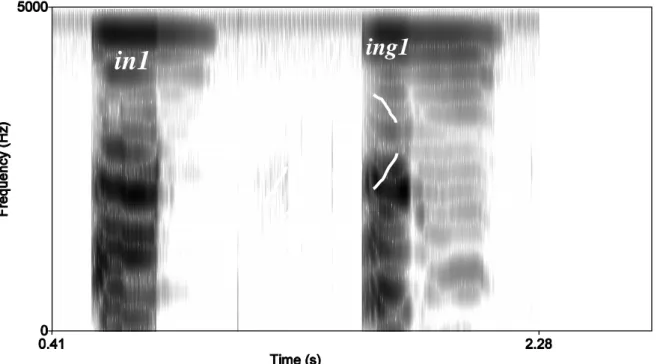

instructed to read these sentences as naturally as possible. The collected sound data were acoustically analyzed by the software Praat 4.3. The acoustic cue adopted to judge the realization of the syllable-final nasals was velar pinch. If the velar nasal, i.e. [ŋ], was pronounced, a fall on F3 and a rise on F2 can be observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Examples of the spectrograms of in1 ‘music’ and ing1 ‘eagle’ 4

6. Results

A Preceding Vowel(3)5 x Merger Type(2)6 x Age(2) x Gender(2) x Ethnicity(3) mixed

five-way repeated measure on the frequency of syllable-final nasal mergers was performed. Results showed three significant effects [Merger Type: F (1,72)=4.68, p<.05; Preceding Vowel: F (2,72)= 52.78, p<.05; Preceding Vowel x Merger Type: F (2,72)= 84.70, p<.05]. The post-hoc Tukey’s analysis on preceding vowels showed that the syllable-final nasals preceded by the vowel [a] were significantly least likely to converge (p<.05); there were no significant differences between the syllable-final nasals preceded by [i], and [ə]. In other words, the hierarchy of syllable-final nasal merger vulnerability is [aN]<[iN]/[əN]. Furthermore, the post-hoc ANOVA on the merger of [ŋ] to [n] showed that the preceding vowel [ə] significantly occurred more frequently than [a] and [i] (p<.05). While in the [n] to [ŋ] merger, the preceding vowel [i] significantly occurred more frequently than [a], and [ə] (p<.05) (Figure 3).

4 The white lines in the spectrogram of ing1 indicate the velar pinch. 5 [a], [i], and [ə].

6 [ŋ] to [n], and [n] to [ŋ].

Figure 3. The preceding vowel x type interaction on the syllable-final nasal merger7

7. Discussion

7.1 Syllable-final nasal merger, in Taiwanese Mandarin or Taiwan Mandarin?

Kubler (1985) categorized syllable-final nasal mergers as a feature of Taiwanese Mandarin. However, the results of the current study do not indicate that significant personal factors, including gender, ethnicity, and age, affect the syllable-final nasal mergers. In other words, Waishengren, the perceived Standard Mandarin speakers in Taiwan, and

Benshengren, the ethnic group who, in general, learn Mandarin as the second language, do

not perform significantly differently on syllable-final nasal mergers. It is implied that the ethnic discrepancy on the performance of syllable-final nasal mergers in Taiwan Mandarin has been leveled. Furthermore, these cross-ethnic mergers are observed in the older generation, implying that the syllable-final mergers might have been “mis-stigmatized” for years.

In fact, this leveling between Benshengren and Waishengren was revealed in previous studies, though not specifically regarding the syllable-final nasal mergers. In Chen (1991a), no significant difference was examined on the tonal performances of Waishengren and

Benshengren. It is noteworthy that the subjects in Chen’s study were born over the course of

a thirty-year period, between 1938 and 1968, approximately crossing two generations, and partially overlapping with the older generation in the current study. Chang (1998) also pointed out that in Taiwan, it was nearly impossible to identify a young speaker’s mother language in terms of his/her Mandarin accent, especially those who were young. Tseng

7 Due to the functional limit of the graphics software, the IPA symbol [ə] cannot be shown in the figure. In

(2003) described her personal experience that her identity of second generation

Waishengren manifested by Mandarin had been weakening, and that the number of people

that could recognize her ethnic identity by her Mandarin accent had been decreasing. 7.2 Syllable-final nasal merger—Inconsistent research results

The current study agrees with Ing (1985) and Chen (1991a) in that the variables [iN] and [əN] perform in different manners. The merger of [iN] is more likely to be velarized. In other words, the merger of [in] to [iŋ] occurs more frequently than in the reverse. On the other hand, in the [əN] variable, alveolarization is the predominant trend. In other words, [əŋ] to [ən] occurs more frequently, as most previous studies reported.

However, discrepancies remain. The backgrounds of the 60 subjects of Taiwan Mandarin in Chen (1991a) were similar to the subjects in the current study because these 60 subjects in Chen (1991a) also consisted of nearly an equal number of Waishengren and

Benshengren in Taipei. In spite of the similar regional origins, similar ethnic backgrounds,

and the similar results of the merger directions, Chen (1991a) and the current study remain discrepant in terms of the results regarding the leading merger. In Chen, [iN] led the syllable-final nasal mergers in all age groups (Figure 4), while the current study indicates that [əN] has been the leading merger (Figure 5). The age range of the subjects in Chen (1991a) was as wide as 30 years, from 19 to 49, with year of birth ranging from 1938 to 1965, approximately one generation earlier than the current study (1951-1960, 1981-1990). Figure 6 illustrates the syllable-final nasal mergers performed by the subjects of similar age in Chen (1991a) and the current study. The discrepancy on the leading merger remains. It is noteworthy that the percentage of each merger may not be comparable due to the stimuli differences.

Furthermore, Chen (1991a:147) suggested that the syllable-final nasal mergers tended to occur on words of low frequency, while the examined words in the current study were all words of high frequency as illustrated in Figure 1.

Meanwhile, as indicated in Figure 5, the current study observed that the [əŋ] to [ən] merger has been performed rather stably for decades, while the [in] to [iŋ] merger, on the other hand, appeared as a new form as its frequency largely increased in the younger group.

Figure 4. Percentage of the mergers of [əŋ] to [ən] and [in] to [iŋ] in each age group in Chen (1991a)8

Figure 5. Percentage of the mergers of [əŋ] to [ən] and [in] to [iŋ] in the two age groups in this study

Figure 6. The comparison of similar-aged subjects’ performances on syllable-final nasal mergers in Chen (1991a) and the current study

7.3 Syllable-final nasal merger—A long-term issue

The instability of Chinese syllable-final nasals also exists in rime books and dictionaries. Chen (1991b:140) pointed out that the syllable-final nasal merger was one of the twomajor trends9 in the developments in Mandarin dialects. Chen further analyzed the

nasal endings of modern Beijing10 Mandarin in three representative systems. They are

(1) the 1932 ‘Standard National Pronunciation’ (as recorded in Guoyu Cidian, 1947, and Chongbian Guoyu Cidian, 1979), which is a revised version of the ‘New National Pronunciation’ of 1924; (2) the 1963 revision known as the ‘Preliminary Draft for the General Table of Standard Pronunciation of Words with Variant Sounds’; and (3) the 1985 revision known as ‘The Table of Standard Pronunciation of Words with Variant Sounds in the Common Speech’. (p.140)

Dictionaries and rime books usually lag behind oral performances in responding to sound change. However, the dictionaries and rime books studied in Chen (1991b) still indicated the instability of syllable-final nasals. For instance, the syllable-final [in] in 皿 (min3 ‘dishes’), and 馨 (xin1 ‘fragrance’), split into both [in] and [iŋ] readings in the 1932 system but were both later officially recognized as ending in [in]; [ən] in both 貞 (zhen1 ‘loyalty’) and 亙 (gen4 ‘long-lasting’) were the results of a change from [əŋ]. The pronunciation of 檳 (bin1 ‘betel nuts’) went through an [in]/[iŋ] two-reading stage in the

9 The other trend studied in Chen (1991b) was the merger of retroflex and dental obstruents. 10 Chen (1991b) adopted the term Peking instead of Beijing.

1932 system and was later changed into an [iŋ] ending in the 1963-1985 system. It is noteworthy that these written records of sound change also agreed with the synchronic studies of syllable-final nasal merger production/perception in that the pairs [in]/[iŋ] and [əŋ]/[ən] were the most unstable ones.

8. Conclusion

The current study examines syllable-final nasal mergers in Taiwan Mandarin. One major finding is that both Benshengren and Waishengren who are native Taiwan Mandarin speakers in fact perform these mergers. In other words, the ethnic gap of syllable-final nasal mergers has been leveled. These mergers may have been mis-stigmatized as one of Taiwanese Mandarin features for decades.

In fact, linguists have studied this issue in Taiwan Mandarin for decades. Results indicated that syllable-final nasal mergers in Taiwan appeared to be not only an issue of long-time confusion, but also a volatile phenomenon. Previous studies and the current study, to various degrees and at a variety of dimensions, disagree with each other. Ing (1985), Chen (1991a), and the current study observed a different result of the [iN] merger direction from Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992). Both Kubler (1985) and Tse (1992) suggested that syllable-final nasals tended to be alveolarized when preceded by [i] and [ə]. Ing (1985), Chen (1991a), and the current study, however, claimed that the syllable-final nasal was more likely to be velarized when preceded by [i].

In addition to the merger direction, the leading merger is another discrepancy between the current study and previous studies. Chen (1991a) and the current study, though agreeing that [əŋ] to [ən] and [in] to [iŋ] were the two predominant syllable-final nasal mergers in Taiwan Mandarin, did not reach an agreement regarding the leading merger. Chen (1991a) suggested that [in] to [iŋ] was likely to be the first to lose its distinction, while the current study indicates that [əŋ] to [ən] is in the leading position. Furthermore, Chen (1991a: 147) suggested that the syllable-final nasal mergers tended to occur on the words of low frequency, while the words examined in the current study, though agreeing with Chen in the directions of the predominant mergers, are all words of high frequency.

References

Ang, Uijin. 1992. Taiwan Yuyan Weiji [The Risks of Language in Taiwan]. Taipei: Avanguard.

Chang, Yueh-chin. 1998. Taiwan Mandarin vowels: An acoustic investigation. Tsing Hua

Chen, Chung-yu. 1991a. Shengdiao de zhuanbian yu kuosan: Taipei butong nianlingqun de quyang [The tonal change and diffusion: From the sampling of different age groups in Taipei]. Journal of Chinese Language Teachers Association 16:69-99.

Chen, Chung-yu. 1991b. The nasal endings and retroflexed initials in Peking Mandarin: Instability and the trend of changes. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 19:139-155.

Cheng, Robert L. 1985. A comparison of Taiwanese, Taiwan Mandairn and Peking Mandarin. Language 61:352-277.

Cheng, Robert L. 1997. Tai Huayu de Jiechu yu Tongyiyu de Hudong [Taiwanese and

Mandarin Structures and Their Developmental Trends in Taiwan II: Contacts between Taiwanese and Mandarin and Restructuring of their Synonyms]. Taipei: Yuan-liou.

Hsu, Hui-ju. 1998. Language shift in a four-generation family in Taiwan. Proceedings of the

6th Annual Symposium about Language and Society, 158-172. Department of

Linguistics, University of Texas, Austin.

Huang, Shuanfan. 1993. Yuyan Shehui yu Zuqun Yisi: Taiwan Yuyan Shehuixue de Yanjiu

[Language, Society, and Ethnicity: A Study of the Sociology of Language of Taiwan].

Taipei: Crane.

Ing, R.O. 1985. Guoyu fayin zai Taiwan: Muqian qushi yu yiban cuowu zhi tantao [Mandarin pronunciation on Taiwan: An analysis of recent trends and errors].

Proceedings of the First International Conference on the Teaching of Chinese as a Second Language, 414-425. Taipei: Shijie Huawen.

Kubler, Cornelius. 1985. The Development of Mandarin in Taiwan: A Case Study of

Language Contact. Taipei: Student Publishing Co.

Li, Tung-ming. 1970. Ju tai waishengji renkou zhi zucheng yu fenbu [The population distribution of the Waishengren in Taiwan]. Taipei Wenxian [Taipei Literature] 11/12:62-86.

Tsao, Feng-fu. 1997. Zuqun Yuyan Zhengce: Haixia Liangan de Bijiao [Language Policy on

Ethnic Groups: A Cross-strait Comparison]. Taipei: Crane.

Tse, John Kwock-ping. 1992. Production and perception of syllable final [n] and [ŋ] Mandarin Chinese: An experimental study. Studies in English Literature and Linguistics 18:143-156.

Tseng, Hsin-yi. 2003. Dangdai Taiwan guoyu de jufa jiegou [The syntax structures of contemporary Taiwanese Mandarin]. MA thesis, National Taiwan Normal University.

[Received 30 September 2006; revised 30 January 2007; accepted 31 January 2007] Department of Applied Linguistics and Language Studies

Chung-yuan Christian University Taoyuan, TAIWAN

Department of Language Literature and Linguistics Providence University

Taichung, TAIWAN

Appendix: The list of stimuli, carrier terms and carrier sentences [-in] 品 作品 這是一部優秀的作品。 金 獎金 大家等著領年終獎金。 林 森林 人類應該要保護森林。 音 聲音 我聽到好熟悉的聲音。 民 人民 國家的希望在人民。 進 改進 這個計畫有待改進。 新 創新 想要進步就要創新。 癮 過癮 大口喝酒真是過癮。 吟 呻吟 有人老愛無病呻吟。 緊 要緊 還是平安比較要緊。 [-iŋ] 影 電影 我不愛看藝術電影。 定 決定 這真是個重大的決定。 景 風景 一路上都在欣賞風景。 名 報名 這次採取通訊報名。 性 女性 我不要扮演傳統女性。 請 邀請 請接受我們的邀請。 命 生命 人人都要尊重生命。 情 事情 這根本不是我的事情。 平 公平 處理事情一定要公平。 驚 吃驚 他的反應讓我很吃驚。 [-əŋ] 陳 雜陳 我的心中五味雜陳。 門 鎖門 我每天要負責鎖門。 神 精神 人人都要有敬業精神。 根 生根 我想在這裡落地生根。 人 大人 我兒子已經長成大人。 本 根本 信用是做生意的根本。 認 確認 訂位記錄需要再確認。 鎮 鄉鎮 台灣有三百多個鄉鎮。 深 資深 那位教練非常資深。 真 天真 那個人真是過份天真。

[-əŋ] 生 學生 我還是個在學學生。 登 刊登 這件事各報都會刊登。 政 行政 政府需要依法行政。 等 平等 社會應追求兩性平等。 增 大增 這結果讓我信心大增。 仍 頻仍 世界各地戰亂頻仍。 爭 競爭 從小到大都要競爭。 成 形成 有個颱風正在形成。 能 可能 什麼事情都有可能。 整 調整 這個組織需要調整。 [-an] 展 發展 教育要注重均衡發展。 產 生產 很多人選擇剖腹生產。 南 指南 旅行時要帶旅遊指南。 案 答案 有些問題沒有答案。 安 不安 我總覺得坐立不安。 三 老三 我在家中排行老三。 反 相反 事情結果正好相反。 山 高山 玉山是台灣第一高山。 辦 舉辦 運動會將於下週舉辦。 戰 挑戰 我們要勇於接受挑戰。 [-aŋ] 房 廚房 我從來沒有下過廚房。 黨 政黨 美國有兩個主要政黨。 放 開放 校慶當天宿舍開放。 尚 時尚 有人愛追求流行時尚。 張 緊張 這狀況令人精神緊張。 方 地方 這是個好玩的地方。 商 招商 政府有時會出國招商。 廠 工廠 工業區內到處是工廠。 讓 禮讓 很多人都不懂禮讓。 抗 反抗 青少年事事都要反抗。

再探台灣華語的音節末鼻音合併:

一個等化但仍多樣的現象

許慧如 謝國平

中原大學 靜宜大學

本研究以語音與社會語言學觀點探討台灣華語音節末鼻音合併現象。 研究發現,戰後由中國來台之新移民(一般所稱之「外省人」)與本省閩南 人之間,於音節末鼻音合併現象上並無顯著差異。此外,本研究亦顯示音 節末鼻音合併方向與鼻音前之母音有關,若該母音為[i],則其後之齒齦鼻 音[n]傾向與軟顎鼻音[ŋ]合併; 若該母音為[ə],則鼻音傾向由軟顎向齒齦合併。此項研究發現與Ing (1985)及 Chen (1991a)吻合,但其中的[iN]合併方

向,則與Kubler (1985)及 Tse (1992)相反。此外,本研究雖與 Chen (1991a)

於兩種音節末鼻音合併方向上得到一致的結果,但對於何者居帶頭地位,

仍未得一致結果。Chen (1991a)的研究結果顯示,[in]Æ[iŋ]的合併頻率較高,

但本研究卻顯示[əŋ]Æ[ən]頻率較高。