國

立

交

通

大

學

經營管理研究所

碩

士

論

文

整體體驗、品牌知名度、品牌聯想、知覺品質、

品牌情感及品牌忠誠度之關係探討

Holistic Experiences, Brand Awareness, Brand

Associations, Perceived Quality, Brand Affect, and

Brand Loyalty

研 究 生:曾祥景

Holistic Experiences, Brand Awareness, Brand Associations, Perceived

Quality, Brand Affect, and Brand Loyalty

研 究 生︰曾祥景 Student︰Hsiang-Zing Tseng

指導教授︰丁 承

Advisor︰Cherng Ding

國立交通大學

經營管理研究所

碩士論文

A Thesis

Submitted to Institute of Business and Management

College of Management

National Chiao Tung University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Master of Business Administration

June 2009

Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China

中華民國 九十八 年 六 月

整體體驗、品牌知名度、品牌聯想、知覺品質、品牌情感及品牌忠誠

度之關係探討

學生: 曾祥景 指導教授: 丁承

國立交通大學經營管理研究所碩士班

摘

要

隨著服務商品化及客製化,體驗經濟時代已經來臨。每個人對真實性都有需 求。體驗是提供真實性的一種有力方式,因此以顧客體驗為中心的管理哲學已經 興起。這可以在 2009 年學術界對顧客體驗此領域的重視看出。本研究順應此研究 潮流,欲連結體驗策略與品牌相關構面之間的關係。其中以整體體驗為投入,品 牌忠誠度為終極目標(效果)。主要的研究目的如下:第一,整合相關理論釐清整 體體驗、品牌情感、品牌權益構面之間的關係。第二,探討體驗策略的效果性。 第三,探討體驗策略的效率性。研究的品牌為自 2003 年 9 月後實行體驗行銷的麥 當勞。實體調查了十七家麥當勞的顧客,總共 313 位。抽樣方法為立意抽樣。分 析方法主要為線性結構模式。研究發現如下:第一,整體體驗、品牌情感與品牌權 益構面之間的關係並非可由氛圍學中的認知-情感或情感-認知理論單獨解釋。因 為在效應層級模式考量在內時,認知-情感的中介效果及經驗層級皆可達成效果而 情感-認知理論的中介效果不成立。第二,體驗策略的效果性而言,顧客對品牌的 情感、知覺品質、品牌知名度/品牌聯想扮演完全中介的角色。其中直接訴諸於品 牌情感的整體體驗的效果大大超過先訴諸於品牌認知層面再訴諸於品牌情感的效 果。第三,就體驗策略的效率性而言,關聯體驗應分最多資源、感官體驗最少。 核心管理意涵為宏觀的規劃整體體驗以有效率、有效果的達成體驗目標。最後提 出結論、限制與未來研究方向。

Holistic Experiences, Brand Awareness, Brand Associations, Perceived

Quality, Brand Affect, and Brand Loyalty

Institute of Business and Management

National Chiao Tung University

Student︰Hsiang-Zing Tseng Advisor︰Cherng Ding

Abstract

As the commoditization and customization of service, here comes the experience

economy. Everyone has a quest for authenticity. Staging experiences is one way of offering authenticity. Therefore, management philosophies that have a focus on

customer experiences have sprung up as can be seen in academic journals in 2009. We follow these research streams and try to relate experience strategies to relevant

dimensions of brand where holistic experience strategies was input and brand loyalty was the final goal. Main research purposes were shown below. First, the relationship among holistic experiences, brand affect, and brand equity dimensions were examined. Second, the effectiveness of experience strategies was examined. Third, the efficiency of experience strategies was examined. The research brand was McDonald’s, an experience stager since September 2003. We physically surveyed 313 customers in 17 chain stores of McDonald’s. Purposive sampling was performed. Analytical method was SEM. Key research findings were as follows. First, unlike atmospherics context, it is deficient to explain the responses of customers under cognition-emotion or

emotion-cognition intervening mechanisms alone in the experience context. More intervening mechanisms should be included such as hierarchy-of-effect model in our study. Second, strategies appealed to the brand affect directly had the larger

effectiveness than those appealed to the cognitive dimensions of brand, and then brand affect. Third, to attain efficiency, relate experiences ranked first and should be assigned the most resource while sense experiences ranked the least. Core managerial implication was to urge experience managers holistically planning their experience strategies to attain the experiential goal effectively and efficiently. Conclusion, limitations, and future research directions were presented in the end.

Keywords:Holistic experiences, hierarchy-of-effect model, cognition-emotion theory, emotion-cognition theory, brand equity, brand affect, strategic resource allocation

Acknowledgement

Before the completion of this research, there are plenty of people and organizations that I will thank to below. First, I have to show my gratitude to my parents and younger brother who have been encouraging me during my hardtimes. Second, I must thank to my advisor Cherng Ding for his selfless sharing of academic knowledge to me and hearty support both mentally and substantially. Third, I have to thank my classmates and juniors of IBM in NCTU for their constant invigorations whenever I feel depressed and in need of their sponsorship of friendship, and for their active behavior in discussing academic affairs with me, making me grow a lot in knowledge on business management. Fourth, I have to be obliged to customers interviewed in McDonald’s for their

indispensable role in the provision of their opinions. Fifth, those hired by us to

distribute questionnaires should be thanked. Sixth, my good friends Steven Chen, Ellen Tsai are worth my hearty thanks for all the happy times together. These happy times has been deeply rooted in my memory and served as the most powerful force to defeat all negative emotions in my reduced situations. Most importantly, this research was partially supported by grant NSC 96-2416-H-009-006-MY2 from the National Science Council of Taiwan, R.O.C. Without the financial support, the implementation of this research will lack efficiency. Finally, I thank IBM of NCTU for all the good old days in my memory and for all the effort dedicated to me as a competitive elite.

Contents

Chinese Abstract………...i Abstract………ii Acknowledgement………...iii Contents………iv Table contents………...vi Figure contents………vii Chapter 1. Introduction………1Chapter 2. Literature review………8

Customer experiences……….………...8

Customer experience management systems ………..12

Holistic experiences………14

Brand equity………....20

Aaker’s brand equity as Gestalt brand equity……….22

Product-market school of brand equity………...25

Customer behavior-based brand equity………...26

Customer-based brand equity………..26

Brand affect………...28

The relationship among experience-based brand equity and affect………...……..29

Chapter 3. Methodology………39

Sampling………...…...39

Research constructs and measurement………...41

Pretest and focus group………...44

Control variables………..……….…...44

Analytical method………...…….46

Chapter 4. Results and discussion………...……48

Chapter 5. Managerial implications………..…………59

Holistically planning of experience strategies……….…………...59

The effectiveness of experience strategies……….…………...59

The efficiency of experience strategies……….………...62

Implications for CEM systems……….………...……...64

Chaper 6. Conclusions………...66

Theoretical confirmation………..……….………...66

Limitations and future research directions……….…...68

Reference……….………...70 Appendix 1.

Reliability and convergent validity for the 2nd order CFA of measurement model………....……….79

Appendix 2.

HLM result under C-E theory- random coefficient modeling………..……..….81

Appendix 3.

Table contents

Table 1. Drivers from traditional to new customers……….2

Table 2. Comparison of traits between traditional and new consumers………2

Table 3. Summary of customer experience management systems………..13

Table 4. Summary of experience types………...17

Table 5. Summary of experiential tools………..…19

Table 6. Summary of experience consumption process………..…19

Table 7. Summary of perspectives on brand equity and corresponding schools………. …………...21

Table 8. The comparison of scope of perception between Aaker’s brand equity and customer-based brand equity……….……25

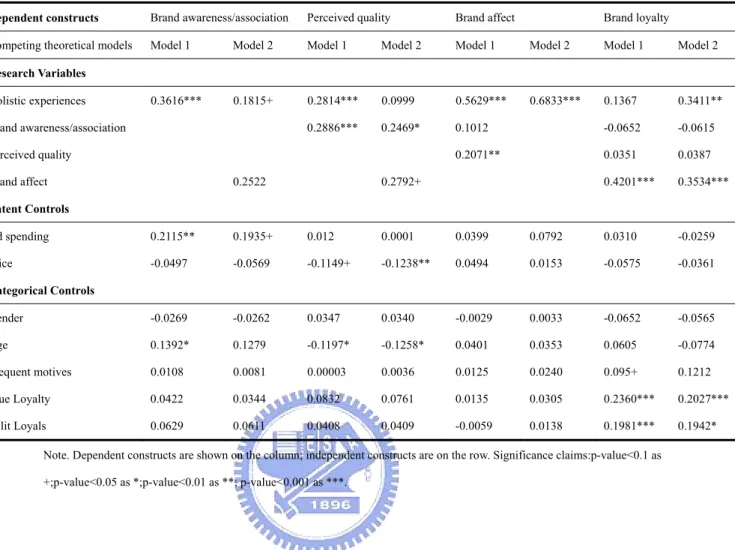

Table 9. Descriptive statistics………...49

Table 10. Summary statistics and correlation between constructs………...50

Table 11. Comparison of CTM(Competitive theoretical models)………50

Table12. Standardized path coefficient estimates for the structural models under model 1 or 2…...51

Table 13. Comparisons among indirect effects under integrated model 1………....54

Table 14. Comparisons among direct and indirect effects under integrated model 2………...54

Figure contents

Figure 1. Integrated framework of model 1 for experience-based brand equity creation………38 Figure 2. Integrated framework of model 2 for experience-based brand equity creation………38 Figure 3. Consequent framework for experience-based brand equity creation under model 1...……….58 Figure 4. Consequent framework for experience-based brand equity creation under model 2…………58

Chapter 1. Introduction

The role of customers has changed from traditional to new owing to macro or specific environmental factors, as shown in table 1, giving rise to overwhelmingly disparate traits from their predecessors shown in table 2. The transition will dominate consumers’ shopping styles in North America, Europe, and Asia in ten years. Therefore, marketing based on those traits caters to the heart of new consumers and is apt to succeed (Lewis and Bridger 2000). The supreme power of new consumers drive the advent of consumers’ realm and so do consumer-focused management philosophies (Austin and Aitchison 2003; Prahalad 2004), including marketing concept, customer satisfaction, customer relationship management , and recently emerging customer experience management. All consumers have a quest for authenticity. The desire for authenticity drives the advent of experience economy (Pine and Gilmore 1998, 2007). One way to offering authenticity is to stage valued experiences. Customer experience management conforms to this trend and becomes a better way to cater to new

customers’ traits and provide authenticity.

In the experience economy, customers seek impressive shopping experiences in the consumption process, not such fundamental aspects as product attributes, functions, and basic benefits (utilitarian features). Schmitt (1999) presented concepts and theories of experiential marketing including strategic experiential modules and experiential providers by integrating literatures on customer experience, sociology, psychology and the like.

Table1. Drivers from traditional to new customers

Drivers Descriptions Impact on customers References

Society ‧ Consumption for desires above physiological needs

‧ Change of consumer sensitivity

Treasuring the value added brought from the brand or product, authenticity

Lewis and Bridger 2000; Pine and Gilmore 2007

Economy ‧ The evolution of economic values to experiences

‧ Commercialization of service ‧ Economic depression

Wanting valued experiences or choices of dollar value (low cost, fashion, prestige, or trend)

Pine and Gilmore 1998 Grewel et al. 2009

Technology Rapid developments of the Internet, virtual simulation, integrated electronic media, media fragmentation

More accessible to acquire and share information

Austin and Aitchison 2003; Lewis and Bridger 2000;Schmitt 1999, 2004; Pine and Gilmore 1998

Competition Aggravating competition due to commercialization of brands and media bombarding

More choices of consumers and more resistance to mass media

Schmitt 1999, 2004; Pine and Gilmore 1998

Pressure groups

The rise of organizations for consumers’ rights, anti-media, and brand communities

The rise of consumerism and resistance to mass media

Austin and Aitchison 2003

Table2. Comparison of traits between traditional and new consumers (Pine and Gilmore 2007; Lewis and Bridger 2000)

Traditional consumers New consumers

Seeking convenience Seeking authenticity

More passive More active

Conforming to the public Seeking personal styles

Less participatory More participatory

Schmitt urged enterprise operators designing brilliant customer experiences to create value for customers by elaborately combining strategic experience modules and experience providers. Building on these spirits, other process perspectives of experiential design such as time dimensions of physical experiences, experience engagement process, and experience bow complemented with experiential matrix to refine customer experience management. Followers including academicians and practitioners agree on experience value creation both for customers and enterprises. By staging valued experiences, customers get indulged in the sweet spot, states of multiple sensory pleasure (Pine and Gilmore 1998), become a wholly person- the ultimate goal of human beings (Lasalle and Britton 2004). With staging sweet experiences enterprise operators will benefit from customers’ loyal behaviors, inclusive of repeated purchase, positive WOM, long-term partnership-being a partner in staging experiences and/or active in defining and implementing their experience motives for enterprises. At that time, customers are employees, and vice versa (Pine and Gilmore 1998, 2007; Schmitt 1999, 2003, 2004; Smith and Wheeler 2003; Carbone 2004; Lasalle and Britton 2004). The aforementioned enhanced the long-term financial performance for enterprises. In addition, it is due to the complex and original nature of experiences that generates inimitability, rareness, and further competitive advantage for enterprises(Smith and Wheeler 2002). Therefore, enterprises must take the initiative to manage customer experience to obtain their gifts.

As to the applications of customer experience to the business management, it serves as means to building brand equity in experiential marketing (Schmitt 1999 2003). Customer experience revitalizes and enhances the original brand assets (Carbone 2004). Brand equity is either coined by wholly new experience designs or reinforced by

integrating new experience designs to the old brand (Smith and Wheeler 2002). The power of brand consists in the hearts of customers, inclusive of all the experiences and feelings by interacting with the brand on a long term basis (Leone at al. 2006). The aforesaid stresses it is of abundant value for enterprises to apply customer experiences to the creation of brand value. Enterprise players need to assess the relationship between their customer experiences and brand values continuously to ensure customer

experiences can enhance brand values.

Brand equity is the most important and comprehensive brand asset set, used for measurement of the enterprise’s brand value for itself. Not until David Aaker put forward the term brand equity in 1990 had this vague term been clearly defined. In addition to measurement of value, brand equity can benefit enterprises in many ways. High brand equity creates a powerful strategic asset, and barriers to entry for

competition (Aaker 1991), increases cash flows, reflecting in the increase of market share, profit and in the decrease of marketing costs (Simon and Sullivan 1993), adds value to the firm’s asset (Kamakura and Russel 1993), makes follow-up effective marketing programs possible such as successful brand extensions (Blackston 1992; Bridges 1992), enhanced efficiency(Smith 1991), makes good permanent, cumulative sales effect (Slotegraaf and Pauwels 2008), attracts human capital for job applicants’ expectations of higher training, promotion, learning opportunities (Delvecchio et al. 2007), leaves much response elasticity for firms to confront marketing activities of competitors(Kish, Riskey, and Kerin 2001), and resists service failure regardless of the practice of service recovery(Brady et al. 2008). The aforementioned benefits indicate the importance of effectively manage your brand to create brand value. In response to

decision-making process, or express a person’s traits or self-image especially important for new consumers (Keller 1993). Therefore, brand equity is also both symbolically important and time-saving tools for consumers.

In sum, consumers attain the very experience motifs or get the sense of authenticity whereas enterprises benefit from staging experiences around the experience value promise made in response to motifs in terms of gifts. That is, experience management can create value both for consumers and enterprises. Despite the quest for customer experience management, there are few quantitative researches in this field. Qualitative studies designed for understanding the basic essence and descriptions of experiences are numerous, making it possible to understand customers’ inner world of experiences. However, knowing the why, how questions without a scientific examination is perilous. More research on the evaluation of the effect of experience strategies planned by the stagers is suggested by Schmitt to complement qualitative researches such as focus groups, in-depth interviews, or ethnographies, especially for the experience strategies on the creation of brand equity. In 2009, the concept of customer experience was formally defined in Journal of Retailing along with some suggested research directions. It is important to understand the relationship between customer experience and perception of the retailing brand. There is a gap which suggests empirically testing the relationship between experience-based retailing strategies and the corresponding retailing

performance metrics (Virhoef et al. 2009). Evaluation of metrics of brand value and customer retention is necessary for retailers to further improve their performance

(Petersen et al. 2009; Grewal et al. 2009). Following this research stream, filling the gap, we empirically test a conceptual framework of experience-based brand equity by

integrating vital theories and concepts presented by academicians and practitioners in the experience, brand, and consumer psychology fields. In this study, experience-based

brand equity creation framework is to use experience strategies perceived by customers to create brand equity. Our research purposes are as follows.

The first purpose is to connect experience strategies to brand equity and simultaneously clarify possible relationship among relevant dimensions, which can

create value both for consumers and enterprises. In response to experience stewardship suggested by Carbone (2004), to better understand customer experiences as the basis of experience planning, more understanding on the relationship among customer cognition, affect, and physical action toward the brand is indispensable. Brand researchers

suggested possible relationship among brand equity dimensions (Aaker 1991; Yoo and Donthu 2001). Experience researchers suggested the possibility that experience

strategies influence consumers’ cognitive, affective, and conative responses toward the brand, with no clear relationship identified among them (Schmitt 1999; Carbone 2004). Also, knowing the relationship can serve as the main focus of customer experience management systems as shown in managerial implication. As you can see in literature review, we will integrate relevant theories to construct two integrated models that will be compared. In turn, we will select a better one to further clarify the relationship among relevant dimensions.

The second purpose is to examine the effectiveness of experience-based strategies. Based on the relationship mentioned above, we suggest possible routes and

the best route to attain the final goal of experiential marketing-brand loyalty in this study. Knowing them will benefit experience managers to plan experience strategies.

The third purpose is to present the way for resource allocation under holistic experiences strategies. The success of experience-based strategies lies in the control of

procedural efficiency (Verhoef et al. 2009). Strategic resource allocation may

subsequently affect corresponding efficiency of touchpoint arrangements. Enterprises all have limited resources. Hence, efficiency of experience-based strategies is desired. To the best of the author’s knowledge, this topic has not been discussed in the customer experience field. In our study, we will allocate strategic resources of different experience modules based on customers’ perception of experiences.

Experience-based brand equity differed from traditional brand management systems in that customers’ experience motifs prioritize. Traditionally brand building process follows strategic brand analysis, brand identity, consistent unique selling propositions and positioning, integrated marketing communication, and finally brand equity creation and controls (Aaker 1991, 1996; Keller 1993). In the process, customers never or seldom rank first (Carbone 2004; Schmitt 2003; Smith and Wheeler 2003). The problem lies in the alignment between the ideal value proposed by managers and the experiences perceived by customers (Nasution and Mavondo 2008). Traditional brand building is to the manipulation of customers’ perception by company’s considerations what experiential brand building is to the manipulation of business strategies by customers’ inner world (Blackwell, Miniard, and Engel 2006). Under the experience economy, the active role of customers justifies traditional brand building process may fade away in attaining company’s goals (Lewis and Bridger 2000; Austin and Aitchison 2003; Carbone 2004). Therefore, experience-based brand building may emerge. It is the experiences perceived by customers that create brand- related responses, not the

evaluation of strategic effect by experts or top managers. The point will be always on customers’ experiences, which we will stress in the conclusion.

Chapter 2. Literature Review

Customer experiences

Experiences occur when customers directly or indirectly respond to events (Schmitt 1999). Events are probably direct, fictitious. However, experiences are authentic due to the fact they are perceived by customers. Experiences are the result or response after all the interactions of customers with the company, company representatives, and the products (Lasalle and Britton 2004; Gentile, Spiller, and Noci 2007). Customer experiences are the bridge, byproduct through which customers contact the company (Carbone 2004). Customer experiences are the subjective, internal responses through direct and indirect interactions between customers and the company (Meyer and Schwager 2007). In the light of provision of experiences, companies stage out

experience providers to induce customers’ experiences toward their brands or products (Schmitt 1999). Experiences are customers’ feelings, cognition, and behaviors toward all planned or unplanned clues (Carbone 2004). It is planned experiences that create value both for customers and companies. Hence, customer experiences are customers’ responses to all the company-planned enclosed experiences carried out by the

experiential media during the consumption process.

Service-dominated economy put emphasis on maximizing customer satisfaction

whereas experience economy stressed customer loyalty that can mirror the level to which companies create value for customers (Pine and Gilmore 1998; Schmitt 2003; Smith and Wheeler 2003; Carbone 2004). In terms of customer satisfaction, many

excluded from our study. The performance of experience management reflected on loyalty (Pine and Gilmore 1998).

The most relevant to customer experiences is the atmospheric research stream (Virhoef et al. 2009). Atmospherics put emphasis on the manipulation of atmospheric elements to stimulate positive consumption affect of customers and further attain positive consequences such as approach behaviors, purchase intentions, customer satisfaction, and so on (Kotler 1973). Clues are categorized as design (interior, exterior), ambience (light, music, scent), and social ones (crowding, employee attributes) (Turley and Milliman 2000); Customers are defined as passive roles in atmospheric context as Behaviorism of psychology claims. They respond passively to marketers’ manipulated clues. Although follow-up researchers have added cognition components and discussed the exact mediating sequence along with affect components to attain behavioral components, the sheer fact is what counts is the experience or meaning enclosed with clues, not the clues themselves (Donovan and Rossiter 1982). In actuality, experiential forms are quite a lot according to experiential researchers claim in Table 3. Overtly stressing the importance of clues on customer responses may possibly assume the equivalence of experience clues brings to customers. Henceforce, atmospherics have shifted to enumerate all the important clues to better manipulate them to stimulate desired responses of customers or have extended to the Internet context. However, atmospherics reviewers presented the constrained view of researches and requested subsequent researchers to develop much more holistic theories (Turley and Milliman 2000). Therefore, researches in atmospherics will be well complemented with more researches to the heart of customer experience. As for the methodology, experimental approach dominates in the atmospheric field in which interested clues are manipulated to influence cognition, affect, behavior intention, and

even real behaviors of customers (Turley and Milliman 2000). However, experimental approach excludes the authenticity of the consumption contexts, and other factors influencing customer in the customer experience, therefore resulting in low external validity in the real retailing context. Experiences are likely distorted in experiments unless good simulation technology such as virtual reality emerges, which is costly. In addition, it is hard to manipulate all the experiences especially under holistic

experiences context. Also, the more authentic the research contexts are, the more inappropriate the experiments can be conducted (Ruane 2005).

It is due to the holistic nature of customer experiences that make it contain broad dimensions. According to our review, customer experiences can be broadly divided into scope-based and strategy-based experiences. Under scope-based experiences, we can further subdivide it into medium-based such as brand, product, and service experiences and process-based such as consumption experiences. The construct brand experience was conceptualized and scale-validated in Journal of Marketing (JM) along with some review of experiences in different contexts. Brand experiences are all the sensory, affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses induced by brand-related stimuli. Product experiences are all the direct, indirect interactions consumers have with products. Service experiences are mostly created by atmospheric, and personnel variables. The aforesaid experiences are medium-based. Consumption experiences occurred when consumers use, consume products, which are mostly concerned with hedonic goals and process-based (Brakus, Schmitt, and Zarantonello 2009). Consumer decision making process was used to explain customer experience by Puccinelli et al.

company-controlled factors to influence marketing and financial metrics (Grewal 2009). The construct customer experience was formally conceptualized in Journal of Retailing (JR) by Virhoef et al. (2009). It is due to the late formal conceptualization of customer experience that delays the previous efforts to unveil this field. Based on the latest scope definition of customer experience in JR, the scope containssocial

environment, service interface, retailing atmospherics, product display, pricing, other channels, retailer’s brand, and previous experience. However, unfortunately there is still no measurement metrics for this scope-based customer experience

conceptualization (Virhoef et al. 2009). Experiential value measures can serve as better measure in the Internet and catalog shopping context (Mathwick, Malhotra, and

Rigdon 2001). Strategic experiential modules measure can evaluate the effect of experience strategies especially for the creation of brand equity (Schmitt 1999), which is strategy-based experiences. Survey has been the main method of experience-related researches. Theme park experience is examined to better understand the relationship among cognitive disconfirmation, affect dimensions such as pleasure and positive arousal, and consequent dimensions such as satisfaction, futuristic loyal intention and willingness to spend without the input of experience perception (Bigne, Andrea, and Gnoth 2005). In this manner, marketers are hard to arrange their experience strategies. A research to cross-culturally examine the effect of shared and individual experiences on brand image, brand associations, brand attitude, brand personality (the aforesaid brand dimensions being the brand meaning), and brand relation was conducted to understand the effect of customer experiences on the establishment of brand relations, indicating the role of brand meaning as a complete intervening mechanism (Chang and Chieng 2006). According to the finding, customers’ implicit aspects toward a brand were understood. However, not deeming shared experience and individual experience higher level factors may lower fit and bias the result. Further, although it was lucrative

for marketers to understand the process of relationship building, it was of little help for them to examine the performance of experience strategies. Based on the previous review, we know that experience management mostly in practice has also been valued by academics. Studying the experiential marketing field can fill the chasm between practice and academics (McCole 2004). Thus, it would be of much value to conduct research following this stream.

Customer experience management systems

The definition of customer experience management systems was proposed as series of steps to integrate activities in the company to attain experience value promise and company goals simultaneously, which was practical in nature (Schmitt 2003). Different systems were shown in table 3. We induct a more complete system in which steps are experience goal-setting, experience exploration, experience strategy,

experience design, experience implementation, and experience control. Experience goals are set such as enhancement of loyalty, emotional value, brand equity or

customer equity. SMART principle is the goal-setting basis. Goals should be specific, measurable, attainable, responsive to changes, and time bound. The aim in experience exploration is to collect ample data, information from inner world of experiences of customers, experiences offerings of competitors, and internal current and past

experiences offered to customers for the establishment of following strategic platform. In addition, these data can be collected simultaneously. Building on the result of the experience exploration, the step of experience strategy is to lay the foundation of customer values creation. In addition, it serves as guidelines for subsequent design,

presenter System

Schmitt 2003 Carbone 2004 Smith and Wheeler 2003

MacMillan and Mc Groth 1997

Meyer and Schwager 2007 Experience goal-setting Goal-setting Experience exploration Customers’ inner world of experience Experience evaluation, Experience audit Defining customer values Mapping the consumption chain Past pattern, Current relationship, Futuristic potential Experience strategy Strategic experience

platform

Experience design Experience design Designing branded

experience for customers Analyzing your customer’s experiences Experience implementation Brand experiences, Customer interface, Continuous innovation Experience implementation Equipping people, delivering consistently

Experience control Control Experience stewardship

Sustaining and enhancing performance Table 3. Summary of customer experience management systems

Experience design is the intervening step between experiece strategy and experience implementation. Design teams are comprised of members from multiple backgrounds. Experience value promise is the screening mechanism of experience design to ensure no deviations of experiences designed. Also, clues, experiences and timing issues should be addressed in this step. Experience implementation is to deliver experience value promise-based experience designs to customers and employees. Also,

organizational culture, leadership of top management, cross-functional collaboration, and human resource management should all reflect experience value promise. The aim of experience control is to ascertain the consistency of experience value promise of all activities, and in this way attain the goal of experience management. The system will hopefully assist enterprises attain the effectiveness of customer experience

management. The core of customer experience management system lies in customer experiences, making it usual to track customer experiences on a continuous basis. Both innovation, and analysis, strategy and implementation, holistic views were required for the system to perform well. The strength points of this system are the focus on what customers value, the ease of coordinating marketing elements to attain synergy, and the cost-effectiveness (Schmitt 2003). In addition, participatory market orientation (PMO) helped the integration effort a lot, making internal and external customers of the company collaborate as a whole to enhance their valued experiences. The effect of participatory market orientation will be reflected on the increment in brand equity. The steps of customer experience management may contain dimensions of PMO-

organizational culture, marketing, human resources, leadership, and evaluation (Ind and Bjerke 2007).

Holistic experiences under experiential marketing

In experiential marketing, companies stage five strategic experience modules to make customers connect to their brands cognitively, affectively, and behaviorally. Holistic experiences as the ultimate goal of experiential marketing is the synergy of five Strategic experience modules. If we define holistic experiences strategically, the holistic experiences planned by the company will reflect on the actual perception of experiences in the consumption process. Sense experiences appeal to sensory pleasures and excitement. Affective experiences (Feel) induce customers’ feelings, emotions, and moods. Cognitive experiences (Think) stimulate convergent, divergent thinking of customers, tempting to change thoughts or opinions of customers on some issues and

people’s needs for self-actualization, self-respect, esteem, and affinity by connecting both customers and companies to the brand or something meaningful (Schmitt 1999; Smith and Wheeler 2003). Two or more combination of the aforesaid strategic experiential modules forms the experiential hybrid with different categories of shared/shared, individual/individual, and individual/shared experiences. Holistic experiences are the ultimate state of individual/shared experience hybrids. Customers’ perception of the holistic experiences is cognitive, affective, and physical in nature (Schmitt 1999; Chang and Chieng 2006). Staging holistic experiences was theoretically proclaimed by Schmitt to attain the final goal of experiential marketing. Planning single experiences respectively without a holistic sense risked reducing the effect of other planned experiences (Schmitt 1999, 2003; Carbone 2004). The key to successful integrated marketing communication consists in the synergy of brand activities, which consists of main effects and various interaction effects, not marginal effects of single experiences (Keller and Lehmann 2007). Practitioners stage holistic experiences to customers and customers perceive them holistically (Smith and Wheeler 2003; Carbone 2004). In essence, customer experiences are holistic including broader dimensions (Verhoef et al. 2009). Therefore, we focus on holistic, not single experiences strategic input. According to Gestalt psychology, experiences must be analyzed holistically to take interactive effects of experience modules into account. That is, it is meaningless analyzing the effect of marginal experiences in the lack of synergy created by their combinations. The nature of holistic experiences justifies its broad influences on customers’ cognition, affect, and behavioral intention. Sense

experiences tend to engage customers’ attention. Feel experiences build affective bonds. Think experiences are related to cognitive activities. Act experiences stimulate

behavioral commitment, loyalty, and intentions. Relate experiences transcend

of the scope of other experiences (Schmitt 1999).

Experiences are implicit attitudes formed through direct interaction with events. Implicit attitudes may impact explicit attitudes (Wilson and Lindsey 2000). Both implicit and explicit attitudes can be broadly relevant to cognition, affect, and behavior intention components. Associative network theory states nodes of cognition, emotion, and proposition interact to determine corresponding behaviors when outside events stimulates schema (Erevelles 1998). The aforementioned all indicates holistic

experiences influences cognitive, affective, behavioral intention of customers from the consumers’ perspective. What if we see from the companies’ perspective? Experiential managers seek to plan holistic experiences based on experience motifs of customers to influence cognitive, affective, conative responses of customers (Carbone 2004). Cognition-emotion theory and emotion-cognition theory all indicated atmosphere perceived in the consumption environment gave rise to customers’ cognitive, affective, and behavior responses in which the mediating order of cognitive, affective dimensions differs. Cognition and affect should coexist to examine environment effects (Lazarus 1991; Bitner 1992; Chebat and Michon 2003). In terms of the combination of attitudes, affective and cognitive dimensions are all important (Ajzen 2001). Under the

experience context, the importances of independence hypothesis is not totally

excluding cognition, but includes both cognition and affect simultaneously (Solomon 2009). Both consumer and company perspectives of experiences indicate the

importance of including cognition, affect, and behavior intentions in the research related to experiential marketing.

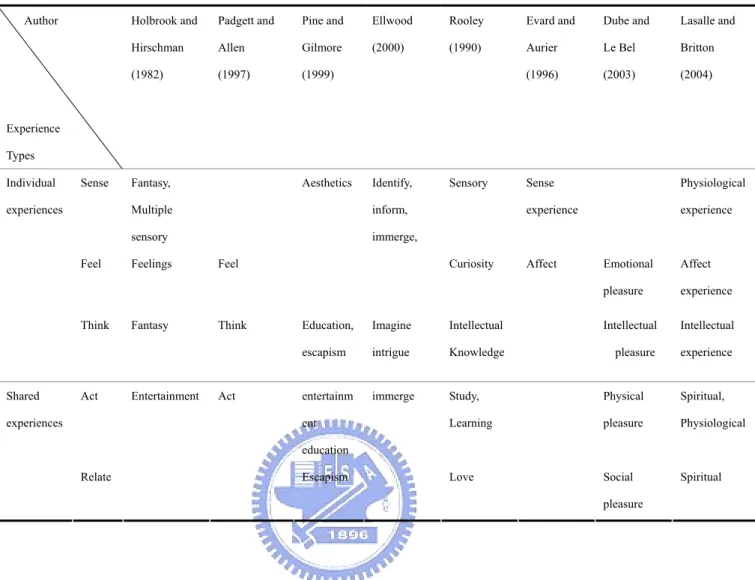

Table 4. Summary of experience types Author Experience Types Holbrook and Hirschman (1982) Padgett and Allen (1997) Pine and Gilmore (1999) Ellwood (2000) Rooley (1990) Evard and Aurier (1996) Dube and Le Bel (2003) Lasalle and Britton (2004) Sense Fantasy, Multiple sensory Aesthetics Identify, inform, immerge, Sensory Sense experience Physiological experience

Feel Feelings Feel Curiosity Affect Emotional

pleasure

Affect experience Individual

experiences

Think Fantasy Think Education,

escapism Imagine intrigue Intellectual Knowledge Intellectual pleasure Intellectual experience

Act Entertainment Act entertainm

ent education immerge Study, Learning Physical pleasure Spiritual, Physiological Shared experiences

Relate Escapism Love Social

pleasure

Spiritual

Holistic value provision approaches can produce sustainable loyalty, and should be focused by the companies to succeed in the long run (O’Malley 1998). Under the holistic experience strategies, it is more likely for companies to attain sustainable loyalty of customers to their brands in which the role of loyalty is of much importance. Therefore, we deemed brand loyalty ultimate goal of holistic experience strategies. The aforesaid mainly addressed the main advantage of this study to empirically test the effectiveness of experience-based strategies on brand equity and the possible relationship among relevant dimensions. However, only retrospective effects of experience-based strategies in brand equity creation are examined, which conforms to the claim that experience matters in the long-term memory of customers accumulated by series of marketing efforts, not temporary one (Pine and Gilmore 1998;Brakus,

Schmitt, and Zarantonello 2009). Also, measuring retrospective effects correspond to the nature of consumer-perceived brand equity, which has been long built in customers’ mind.

Strategy-based customer experiences defined by Schmitt conforms to the most important experiential value promise of the customer experience management for experience value promise serves as guiding principles for experiential design,

implementation, and controls. Therefore, that strategy-based customer experience plays a key role in customer experience management drives us adopting it as the input

variable (Schmitt 2003). Different researchers had disparate views on experiential types, media, and consumption process. Extant experiential types were presented in table 4 while experiential media, consumption process in the experience context in table 5, and table 6, respectively. Strategic experiential modules served as the most complete typologies of experiential types, as the most representative and adopted scale in the experience research (McCole 2004; Chang and Chieng 2006) with firm

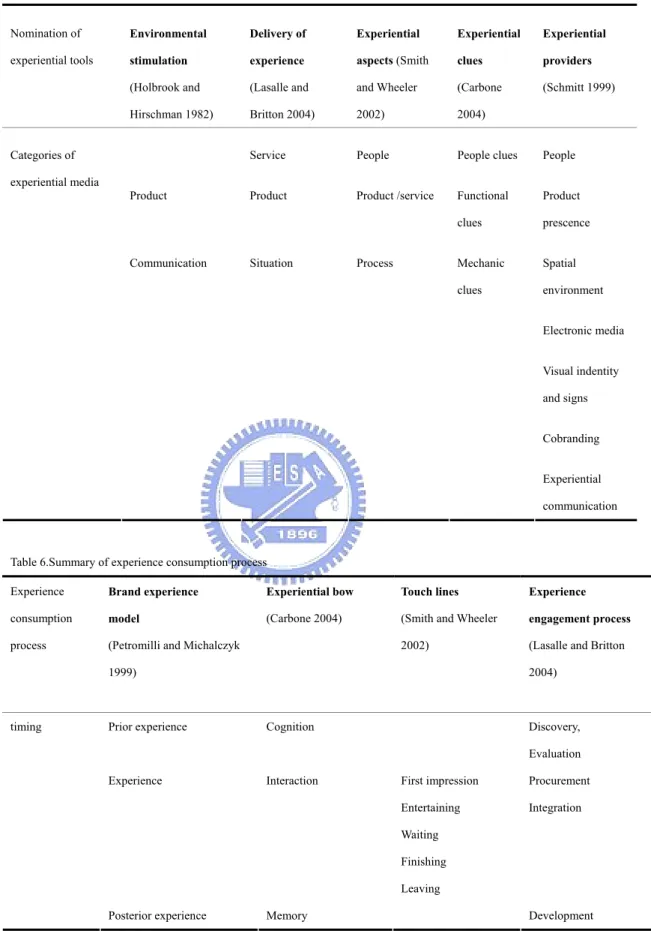

theoretical basis. Also, the research purpose of this study is to examine the effectiveness of experience strategies. Therefore, we adopted its strategic view of customer experience to examine the brand equity creation. In addition, experiential providers (Experience providers) defined by Schmitt as experiential media have broader scope and detailed descriptions. Experience engagement process defined by Lasalle and Britton have specific decompositions and depictions of consumption process, and broader scope, which two helps a lot for marketers to plan their experiential design.

Table 5.Summary of experiential media Nomination of experiential tools Environmental stimulation (Holbrook and Hirschman 1982) Delivery of experience (Lasalle and Britton 2004) Experiential aspects (Smith and Wheeler 2002) Experiential clues (Carbone 2004) Experiential providers (Schmitt 1999)

Service People People clues People

Product Product Product /service Functional

clues Product prescence Spatial environment Electronic media Visual indentity and signs Cobranding Categories of experiential media

Communication Situation Process Mechanic

clues

Experiential communication

Table 6.Summary of experience consumption process Experience

consumption process

Brand experience model

(Petromilli and Michalczyk 1999)

Experiential bow

(Carbone 2004)

Touch lines

(Smith and Wheeler 2002)

Experience engagement process

(Lasalle and Britton 2004)

Prior experience Cognition Discovery,

Evaluation

Experience Interaction First impression

Entertaining Waiting Finishing Leaving Procurement Integration timing

Brand equity

Literatures on brand equity indicated the brand experience trend and its research value. More researches on the process and ways strategy-based experience influence brand equity and on the positive or negative effect of experience on brand equity were requested (Keller and Lehmann 2007). The measurements of brand equity varied as perspectives and schools as shown intable 7. The definitions of brand equity also varied as perspectives. In marketing, it is created in consumers’ mind, real action, loyalty behaviors, or brand’s performance in the marketplace whereas it is reflected on the financial value that the brand accrues. However, Brand equity can be broadly defined as the value added brought by the brand.

There are perspectives of finance, marketing, and the combination of both. Given the focus of customer experience management on customers, evaluation of the

experience may precede financial performance of company (Schmitt 2003; Smith and Wheeler 2003; Carbone 2004). Financial data on customers in the company were less available. The effect of financial performance metrics was short-run (Cobb-Walgren et al. 1995). However, customer experience management is a long-term process to constantly track experience motifs and integrate the changes into the strategy to boost their loyalty. Therefore, we focuses on marketing perspective of brand equity. In the subsequent paragraphs, we review different subdivisions of brand equity of marketing perspective to further subdivide and clarify their contents.

Perspectives Scope Schools Measurements of brand equity Customer

perception

Brand images and brand loyalty (Shocker and Weitz 1988).

Combinations of evoked thoughts, feelings, cognition, and associations in consumers’ mind (Kim 1990). The functional and nonfunctional values in consumers’ mind endowed by the brand to physical product (Farquhar 1990).

Fundamental equity plus value added equity-mostly brand relationship (Blackston 1992). Perceived value, brand leadership, intangible value (Kamakuma and Russell 1993). Brand knowledge of customers to a certain brand (Keller 1993).

The overall preference of customers toward a brand, not explained by objective attributes. Price premium determined by customers (Park and Srinivasan 1994).

Variables on perceived quality, brand associations, brand awareness (Cobb-Walgren et al. 1995). Cognitive utilities and benefits added on product by the brand name (Lasser, Mittal, and Shama 1995). Overall quality and choice intention.(Agarwal and Rao 1996)

Product-market Market position and the potential for brand extension (Tauber 1988). Price premium compared to competitors (Mullen and Mainz 1989).

Share of category requirements, market share, relative market price, and channel coverage(Aaker 1996). Market share, relative price added by the brand (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001).

Revenue premium estimated by product-market data (Ailawadi et al. 2003). Brand intercept measures by store-level quarterly sales data (Sriram et al. 2007). Marginal

Customer behavior

Real repurchase behavior as shown in brand loyalty(Aaker 1996). Marketing

perspective

Holistic Gestalt The weighted combination of perceived quality, brand awareness, brand associations, and brand loyalty (Aaker 1991, 1992)

Brand equity ten contains scopes from consumer-perceived and product-market sources (Aaker 1996). Micro The added credibility due to brand names(Bonner and Nelsen 1985)

The increment of discounts of cash flows in the future by the brand name(Simon and Sullivan 1993) Value added from acquiring a certain brand(Mahajan, Rao, and Srivastava 1994)

The cash flow increments due to the brand(Leuthesser 1988) The change of stock price(Simon and Sullivan 1993)

The demand for launching a new brand plus the probability of success(Simon and Sullivan 1993) Financial

perspective

Holistic Interbrand evaluative dimensions of brand strength(Penrose 1989) Financial World’s yearly evaluation of brands(Ourusoff 1993) Mixed

perspective

The combinations of brand associations and behaviors of customers, channel members, company, which can produce higher profitability, competitive advantage compared to those unbranded.(A.M.A 1988)

Brand equity ten, combined with other financial measures such as stock price, reallocation cost, approaches. (Aaker 1991, 1992, 1996) Measurable financial values attributed to relevant brand building activities(Smith 1991)

Customers’ knowledge of customer-based brand assets plus financial brand values (Allard, Jos, and Hans 2001) Table 7. Summary of perspectives on brand equity and corresponding schools

Aaker’s Brand equity as Gestalt Brand Equity

Brand equity is comprised of brand awareness, brand associations, perceived quality, brand loyalty, and proprietary assets. The first four is customer perceived and created by the product whereas the last one is to coin competitive advantage for the company. These dimensions of brand equity are correlated. However, the respective importance of brand equity dimensions differs from industries (Aaker 1991 1992 1995 1996). Brand associations is a cognitive variable (Dobni and Zinkhan 1990; Blackston 1992). Brand associations is a differentiated belief (Blackwell, Miniard, and Engel, 2006). Perceived quality was the middle degree of evaluation of all the intrinsic and extrinsic cues of the product, with intrinsic cues evaluated more during consumption, and more cognitive quality when consumers are more able to assess attributes before purchase (Zeithmal 1988). Perceived quality was mainly about the evaluation of brand function (Aaker, 1996). It was the overall subjective evaluation of the quality of brand (Olshavsky 1985). Perceived quality is an inferential belief (Blackwell, Miniard, and Engel 2006). Perceived quality in the serviece context was mostly cognitive

evaluations in nature, lacking affective evaluation (Klaus and Maklan 2007). Therefore, perceived quality is cognitive in nature. Brand loyalty can reflect futuristic behavioral intention (Aaker 1996; Zeithaml 1996). The direct experiences of customers give rise to attitudes that better predict true behaviors across all experiential contexts than indirect experiences (Ajzen 2001; Blackwell, Miniard, and Engel 2006). Thus, only behavior-intentioned brand loyalty was analyzed. Other assets of brand equity may

Increased resources will make it possible for company to invest vehicles for the purpose of satisfaction of employees to lower turnover rates. Lowered turnover will retain employees for a long run, with their abilities, and experiences enhanced continuously, which further triggers customer satisfaction and loyalty. Positive word-of-mouth will attract both new customers, and employees as strategic, and the most valuable assets for the company (Reichheld 1993). Therefore, the core of strategy lies in the customer’ loyalty to your brand. Overall, brand equity defined by Aaker has a broad scope, including customer perception, customer behavior, and some measures of market position of the company such as market share, profit. Therefore, Aaker’s brand equity contains customer-based brand equity, company’s perspective of brand equity, and behavior-based brand equity. Compared to other definitions of brand equity of marketing perspective, Aaker’s brand equity is holistic or gestalt. We call it gestalt brand equity subsequently. However, it lacks affective nature.

Aaker’s gestalt brand equity conforms to the school of Gestalt psychology. Gestalt psychologists indicated the importance to include the overall facets when analyzing human behaviors. In this manner, the more holistic, the better. In this way, stimuli, cognitive, affective, and behavior states must be put into analysis simultaneously. To neglect one of them is unwise. To assemble individual researches to better understand the whole phenomenon is also problematic. It is meaningless to study partial

phenomenon for addition of parts are not equal to the whole (Foxall 1996; Benjamin 2006). As Aaker claimed, brand equity ranges across customer’s cognitive evaluation, behavioral intention, true behaviors, and strategy

In addition, the dimension of other proprietary assets attributed itself to reflecting market competition without much correlation with consumers. It is of much value to companies for the creation of competitive advantage. However, given high relevance of experiences to customers, the dimension of other proprietary assets is less important for experience-based researches, thus excluded (Pine and Gilmore 1998; Schmitt 1999; Carbone 2004; Lasalle and Britton 2004) . Also, dimensions of market performance were excluded from our research because customer experiences are highly related to customer’s inner world (Pine and Gilmore 1998; Lasalle and Britton 2004). Without satisfaction of inner world, it is impossible to have good enterprise performance.

Aaker’s brand equity has a broader scope that includes cognition and behavioral intention to correspond to what Strategic experience modules claims, views customer experiences as the highest level of brand associations to reflect its importance and put brand loyalty as the final goal that corresponds to the final goal of customer experience management, as indicated intable 8. In addition, to the best of author’s knowledge, Aaker’s definition is the mostly adopted one. Different industries result in different importance of brand equity dimensions, the relationship among relevant dimensions. Therefore, it is much better to discuss them with a broader brand equity scale to lower the risk of neglecting important dimensions. We can clarify important dimensions of brand equity through empirical test (Aaker 1996). Also, broader dimensions ensure posterior diagnoses, which are vital for formulation of experience strategies, and conform to broad nature of experiences. Thus, we adopted Aaker’s brand equity as criterion of experience strategy.

Gestalt brand equity Customer-based brand equity Researchers Aaker 1991 1992

1995 1996

Keller 1993 Park and Srinivasan 1994

Cobb-Walgren et al. 1995

Lassar et al. 1995

Cognition Brand awareness Brand associations Perceived quality Brand awareness, Brand associations Multi-attribute attitude models Brand awareness, Brand associations, Perceived quality Brand values, Brand performance, Social images

Affect Brand identification/

attachment, brand trust

Behavioral intention

Brand loyalty

Table 8. The comparison of scope of perception between Aaker’s brand equity and customer-based brand equity

Product-market schools of brand equity

Brand equity comes from the leadership of the brand in the market or from the potential for brand extension. These measures should reflect brand performance in the marketplace (Aaker 1996). Enterprises create values by lending their brand power by brand extension to different product categories or acquiring powerful brands in the market and then extending them. Brand extension can benefit enterprises from increased advertising efficiency, customer acceptance rate, brand synergy, barriers to entry for competitors, opportunities for market entry, and decreased risk of failure (Tauber 1988). Brand equity is also the degree of the price premium (Mullen and Mainz 1989). The above put stress on the company’s comparative strength over its competitors based on market competition, but not on customers. It is what company’s perspective of brand equity is all about. Therefore, the point is to manage and leverage

the powerful brand for the purpose of profitability. Brand equity defined from the perspective of company is largely defiant from the spirit of experiential marketing or customer experience management for the superiority of company’ s interests over customers’ inner world. Thus, it is not well suited as the criterion of experience-based strategies.

Customer behavior-based brand equity

Sometimes, brand equity can be measured by real customer purchase data. In this manner, mostly it is brand loyalty (Aaker 1996). Scanner data can be used to track customer behaviors (Kamakura and Russell 1993). Behavior data such as frequency of repurchase, quantity of purchase, and purchase probability were collected and analyzed. The strength was the objectivity compared to other customer perceived brand equity components. Too emphasized on the behavioral aspect of customers may ascribe itself to behavioralism of psychology. In this manner, the emphasis was put on stimuli and the response. However, in the customer experience research, customers were not so stupid to do the response desired by the marketers. Few brand researchers adopted this view. This definition of brand equity may not apply.

Customer-based brand equity

Customer-based brand equity (CBBE) has been the mainstream of brand equity researches. The most recognized has been the Keller’s (1993) view of CBBE, which defined it as consumers’ differential responses to the same marketing stimulus owing to the brand knowledge. Individual customers are level of analysis. Differential effects

recall. Brand associations were categorized according to their levels of abstraction. Brand attributes, benefits, and attitudes listed in ascending abstraction. Other

dimensions of brand associations included the strength, favorability, and uniqueness.

Customer-based brand equity was composed of brand associations. It was

subdivided as brand value, brand performance, social images, brand identification and attachment, and brand trust (Lassar et al. 1995). In this manner, affective and cognitive components of customers were included. However, the scale lacks discriminant

validity for some higher correlations among factors. Customers’ evaluation of functional and nonfunctional product attribute benefits was also defined as CBBE. Fundamental equity and value-added equity also comprised CBBE. Fundamental equity, inclusive of strategic marketing mix, brand image planning of the company, was the planning facet of company. Value-added equity was brand relationship. Brand equity was mainly comprised of brand relationship between consumers and companies, cognitive, affective, behavioral aspects included (Blackston 1992). However,

relationship is at least bilateral, making it inappropriate for experience-response model as in this study. Scholars in customer-based brand equity considered brand knowledge triggered subsequent behaviors. Cognitivism in psychology holds the role of cognition to determine people’s attitudes and propositions toward others (Foxall et al. 1996; Benjamin 2006). Therefore, customer-based brand equity corresponds to cognitivism. As to the measurement of customer-based brand equity, direct and indirect methods are existent for the measurement of brand associations. Direct method acquired customer’s knowledge toward a brand by asking customers directly, resulting in possible

concealment of true fact. Criteria for brand knowledge induced by direct method included brand extendibility, brand loyalty, price premium, and revenue premium. On the other hand, indirect method probed customers’ knowledge toward a brand by

projective techniques such as sentence completion, elaboration of pictures or free association. Brand Concept Map dividing brand associations into core associations and related direct associations and indirect associations also emerged to understand

association networks of consumers (John et al. 2006). Brand awareness is measured by reminded recognition or unaided recall toward the brand. All in all, the very aim of customer-based brand equity creation process is to strategically build desired

knowledge structure in customer’s mind. In this manner, strategic input such as brand identity planning, and measurement of customer knowledge are deemed a continuing brand building process. Brand equity is created in the mind of customers. Therefore, continuous measurement of knowledge structure of customers is a premise for well-planned brand identity strategies to happen. CBBE put much emphasis on the cognitive part of brand perception. However, brand loyalty as the final goal of experience-related researches does not justify using CBBE as the criterion. Also, sometimes experiences can influence full scopes of customer perception

simultaneously as Strategic experience modules claims.

Brand affect

Brand affect is the overall liking or disliking of a brand (Foxall et al. 1996). Brand affect is a brand’s potential to elicit positive affect in the average consumer as a result of its use (Chaudhuri and Holbrook 2001). Experiences sensed in the product or brand use result in the brand affect that was hedonic in essence (Voss et al. 2003). Therefore, there are three approaches to define brand affect. The first one is overall, the second one is directional, and the third one is specific. Based on Strategic experience modules,

Hirschman 1982). Affective literature stressed the importance of simultaneous including cognitive and affective dimensions to complement the deficiency of cognition alone in explaining consumer behavior (Erevelles 1998). Literature in the online atmospherics field indicated atmosphere did not impact various consumption consequences unless it was mediated by the affective dimension (Eroglu et al. 2003). Literatures on customer experience put emphasis on the importance of affect in the retailing environment (Puccinelli et al. 2009). Experiential values perceived in the environment can influence the affective dimension toward the brand (Voss et al. 2003). Therefore, we included affective dimension toward the brand into experience-based brand equity framework. In order for the consideration of formulation of experience value promise and experiential design, the more specific the brand affect is, the better.

Based on the aforementioned review, we have the following conclusions. First, customer experience researches should focus on holistic experiences, not single experiences or a combination of them. Second, Aaker’s customer-perceived brand equity is used as the criterion under holistic experiences strategy. Third, affect should be taken into account in the study related to experiential marketing, in this study, specific hedonic brand affect owing to our interest. Fourth, improving brand loyalty is the final goal of experiential marketing if it is used to increase brand equity.

The relationship among holistic experiences, brand equity dimensions and brand affect

The experience-response model indicates experiences can stimulate consumers’

cognitive, affective, and physical responses (Carbone 2004). Also, the relationship among these responses may be correlated, though not identified. We propose the

complexity of experiences justifies explaining the relationship among cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions by integrating more intervening mechanisms.

Hierarchy-of-effect model has been applied to the discussion of attitude formation of

consumers when encountering marketing stimuli such as advertising. There are three categories of hierarchies. Standard learning hierarchy features high involving

processing of information. In this manner, stimuli influence cognitive states first, affective states the next, and the last behavioral intention. Low involvement hierarchy features behaviors triggered by low level cognition of the stimuli or simply stimuli. Only after purchase can affective evaluation occur. The last is the experiential hierarchy featuring the affective states triggered in the consumption may induce corresponding behaviors. After the consumption, consumers recalled the event (Solomon 2009). In this study, brand loyalty was deemed the final goal of our framework, thus, the final impact criterion always being brand loyalty to reflect behavioral intention. In this manner, affect and cognition responses under experience strategies may work as complete or incomplete mediators in forming brand loyalty. In environmental psychology, S(Stimulus)-O(Organism)-C(Consequences) framework dominated (Donovan and Rossiter 1982) where different theories claimed disparate intervening sequences of affective and cognitive responses in the organism.

Cognition-emotion (affection) theory(C-E theory) indicates the consideration of

relationship between the person and the environment is the necessary, sufficient condition for a person to form emotions in experiences perceived in a consumption environment (Lazarus 1991). When customers perceived various experiences, cognition impacted first, followed by emotions, and in the end induced behavior

relationship among customers’ cognition, affective, and consequent variables without the input of experiences. Emotion (affection)-cognition theory (E-C theory) also addresses the intervening sequence of affect and cognition responses under a consumption environment (Bitner 1992). In response to servicescape model, the theories proposed emotions formed without the cognitive input for customers mostly thought they had just experienced, not giving much thought to the experiences. Experiences perceived in the consumption environment triggered emotions first, then cognition, and the last behaviors. Both C-E and E-C theories work as intervening mechanisms of cognition and affect of consumers under a certain environment, claim the simultaneous inclusion of affective and cognitive dimensions, and clarify the complete mediating role of cognition and affect between the environment and

behavioral intention. Thus, under the experience context formed by holistic experience strategies to create brand equity, consumers’ affective dimension toward the brand as affective responses of consumers, perceived quality, and brand awareness/association as cognitive responses of consumers may function as complete mediators. Based on the aforementioned review, brand awareness/associations, perceived quality, and brand affect may work as complete or incomplete mediators for holistic experiences to

influence brand loyalty in which the possible intervening relationship may be cognition to affect or affect to cognition.

In turn, we further integrate other theories. According to the nature of Strategic

experience modules, they will influence cognition, affect, and behavioral intention

simultaneously or in a certain route defined by the hierarchy-of-effect model. However, customers themselves are active participants in the experiential process, not the passive roles as they were in the face of traditional advertisements. Hence, experience may stimulate complex internal responses for customers. Customers are able to deal with

cognitive and affective resonance synchronically (Keller 1998; Carbone 2004). Thus, Schmitt suggested interdependence of impact routes defined by hierarchy-of-effect model under the experiential context. Experiential wheels serve as the planning tool for Strategic experience modules. Staged holistic experiences can be related to dimensions of brand equity. According to branded experience, holistic experiences could be coined by product/service, people, and process clues, further cultivating customer’s loyalty toward the brand. In this end, higher loyalty gives rise to financial performance. Customer’s satisfaction cannot predict customer’s loyalty, though. Therefore, the strategic role of brand loyalty was ascertained (Smith and Wheeler 2002). The model also proposes brand asset can be revitalized by staging valued experiences. As to the

relationship between the brand and the experience, brand values rested on brand

assets. Holistic customer experiences play focal role in creation of brand assets. Meanwhile, customer experiences can trigger customer loyalty, advocacy, bringing about short-run or long-run financial success, and competitive advantage for the company. In this study, that holistic experiences create brand equity includes the proposition that holistic experiences create brand assets. Also, brand loyalty’s role is stressed by viewing it as the final goal (Carbone 2004). Brand experience model indicated all the experiences from interaction between the person and the brand influence the person’s perception toward the brand and create brand value. The model shows the viability to discuss the process of holistic experiences to creating

customer-perceived brand equity (Petromilli and Michalczyk 1999). Systematic model

of the predecessors and the consequences of brand presented a system in which the

quantitative, qualitative measurements used to evaluate their effects of successfully building the right attitudes in consumer’s mind. The former includes budget or

expenditures whereas the latter contains judgment from managers or experts about the uniqueness, consistency, relevancy, specificity of strategies and tactics. Therefore, the framework to discussing the creation of brand equity under experience strategies is viable. However, the effect of experience strategies cannot be measured based on expenditures or judgments of insiders in that the very point is what customer perceived about the experiential modules planned by the company as holistic experiences. Even if insiders deem the strategy effective, customers will not agree to. Therefore, what company planned as holistic experiences must be perceived before they are effective. The systematic model indicates the viability that strategy-based customer experiences build what customers feel, think about the brand, and then corresponding behaviors conducted to reflect them (Keller and Lehmann 2006). Good service delivery increases the efficiency of memory retrieval for customers. Good service delivery also

strengthens customers’ impression of the brand experience (Chase and Dasu 2001). Advertising, word of mouth, experiences of product built brand awareness (Kotler 2006). Experience is the highest level of brand associations (Aaker 1996). Brand associations can be built on experiential benefits (Keller 1993, 1998). Associations constituting brand images included experiential ones (Park, Jaworski, and Maclnnis 1986). When consumers consume product, they base their evaluation on intrinsic and extrinsic cues. Perceived quality is further formed based on the evaluation (Zeithmal 1988). The evaluation of functional clues forms perceived quality (Carbone 2004). Perceived quality is part of the result of interactions with the brand in the consumption, suggesting experiences can impact perceived quality (Holbrook and Corfman 1983). Customers predict quality of the product based on cues of brand or product (van Osselaer and Alba 2000). Experiences in a certain atmosphere triggered pleased and