京劇鑼鼓與爵士鼓音樂的口頭再現:

功能性核磁共振造影研究

摘要

許多音樂文化都使用無意義的音節來代表打擊樂器聲響,對於「主動的聆 聽者」而言,聆聽打擊樂時跟著在心中默念,可以幫助他們掌握音樂。由 於代表打擊樂聲響的音節在聲響特質上與原本的打擊樂頗有差距,因此, 打擊樂的口頭再現必須透過「連結學習」。本研究使用功能性核磁共振造影 來研究打擊樂的口頭再現所涉及的神經歷程,第一個實驗招募了戲曲戲迷 作為受試者,第二個實驗招募了爵士鼓手作為受試者。這些受試者的大腦 活化將從「聽覺鏡像神經元系統」的概念去探討,此系統主要由顳葉後方 區域與背側前運動皮質所組成。 關鍵字:功能性核磁共振造影;打擊音樂;音節序列;鏡像神經元;連結機制Oral representations of Beijing opera percussion music and

jazz drum music: fMRI studies

Abstract

Numerous music cultures use nonsense syllables to represent percussive sounds. Covert reciting of these syllable sequences along with percussion music aids active listeners in keeping track of music. Owing to the acoustic dissimilarity between the representative syllables and the referent percussive sounds, associative learning is necessary for the oral representation of percussion music. The neural processes underlying oral rehearsals of music were explored by using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). The first experiment recruited Xiqu fans and the second experiment recruited skilled drummers. The brain activity of these participants will be discussed within the framework of auditory mirror neuron system, which is mainly constituted by the posterior temporal regions and the dorsal premotor cortices.

Keywords: fMRI; percussion music; syllable sequence; mirror neuron; association mechanism.

一、前言

大腦造影技術的成熟,讓音樂心理學的研究在近十年有了突飛猛進的發展,然 而從一個較宏觀的角度來看,音樂認知的神經科學研究仍然失之片面,因為研究題 材多半集中於西方藝術音樂,而研究議題也偏重於音階(Neuhaus, 2003, Brattico et al., 2006, Maeshima et al., 2007)、音程(Zatorre et al., 1998, Trainor et al., 2002, Itoh et al., 2003)、旋律(Klein et al., 1994, Patterson et al., 2002, Tervaniemi and Hugdahl, 2003, Kuriki et al., 2005, Brown and Martinez, 2007, Minati et al., 2008)、和聲(Maess et al., 2001, Koelsch, 2005, Koelsch et al., 2005, Loui et al., 2005, Steinbeis et al., 2005,

Koelsch, 2006, Poulin-Charronnat et al., 2006, Steinbeis et al., 2006, Koelsch et al., 2007, Koelsch and Jentschke, 2008, Ruiz et al., 2008, Steinbeis and Koelsch, 2008)等,跟音高 有關的音樂面向。然而,世界上仍有不少音樂種類並非像西方藝術音樂(德文所謂 的 Tonkunst)那麼注重音高資訊,反而更注重音色、節奏等其它的音樂面向,例如 遍布於全球各文化的打擊樂。 人類最早使用的音樂,可能是不具音高訊息的打擊樂。從跨物種比較的觀點來 看,與人類血緣最近的許多大猿,都具有類似打擊樂的音樂活動,但牠們卻不具歌 唱能力,可見打擊樂應該比歌唱更早出現於人猿科(hominidae)的演化史之中。首 度提出「大猿的打擊樂」的演化生物學家 Fitch 指出,雄性大猩猩習慣以搥胸來示 威,黑猩猩喜歡拍打樹根或其他的中空物體,而巴諾布猿(bonobo)則可以在敲擊 物體時保持穩定拍子達 12 秒(Fitch, 2006)。這三個物種與人類從演化樹上分家,至 今不過才六百萬年左右。雖然打擊樂應該比歌唱更早出現於人類文明之中,但有關 打擊樂的神經科學研究至今仍然相當缺乏,與諸多研究歌唱的神經科學論文不成比 例(Perry et al., 1999, Callan et al., 2000, Kleberg et al., 2000, Brown et al., 2004,

Ozdemir et al., 2006, Gunji et al., 2007, Zarate and Zatorre, 2008)。

本文將簡述兩個研究計畫「非旋律性打擊音樂的口傳:功能性核磁共振造影研 究」(以京劇鑼鼓為研究材料)、「爵士鼓手演練音樂的神經基礎:功能性核磁共振 造影研究」的部份成果,探討打擊樂演練的神經基礎。這些跨領域研究皆為筆者與 台大心理學系教授(周泰立、陳建中)及電機系教授(陳志宏)合作完成,部份成 果已經發表於認知神經科學的國際期刊(Tsai et al., 2010)。在本文中,筆者將不會深 入闡述大腦生理機制與功能性核磁共振造影的原理,而將重點置於音樂演奏與音樂 教育的面向,在二十一世紀的音樂學中,介紹一些跨學科、跨文化的研究趨勢。

二、音樂演練與器樂的口頭再現

音樂的演練亟需聽覺皮質與運動皮質之間的密切合作,以便根據即時的聽覺回饋,操控並調整雙手的運動(Munte et al., 2002)。大腦皮質(cerebral cortex)可分為

額葉(frontal lobe)、頂葉(parietal lobe)、顳葉(temporal lobe)、枕葉(occipital lobe)

等腦葉,其中掌管運動功能的腦區主要位於額葉的後半部,掌管聽覺的腦區則位於 顳葉的上半部。運動皮質與聽覺皮質都具有階層結構,較低階的聽覺處理在初級聽 覺皮質(primary auditory cortex)中進行,然後再將訊息送到聽覺聯合皮質(auditory association cortex)作進一步的處理;動作的計畫與執行則相反,較高階的前運動區 (premotor area)先計畫動作,然後再送到初級運動皮質(primary motor cortex)去 執行。

學習音樂者除了照著樂譜演奏之外,仔細觀察與聆聽老師的示範,也是一種極 為重要的學習途徑。關於模仿的神經機制一直是個謎,近年新興的模仿理論則奠基 於鏡像神經元(mirror neurons)的發現。鏡像神經元在個體執行、觀看、傾聽動作時 皆會活化(Gallese et al., 1996, Rizzolatti et al., 1996, Kohler et al., 2002),鏡像神經元 系統是大腦處理模仿學習的核心,這方面的研究多半聚焦於視覺的鏡像神經元系 統,研究聽覺鏡像神經元系統的學者相對較少。

聲音序列(sound sequence)可以激發聽眾腦中的動作模擬(motor simulation),

也就是跟著音樂的進行,想像做出先前與聲音連結在一起的動作,因此,「聽覺-

動作」神經迴路會在主動聆聽(active listening)時活化。在神經科學領域中,主動 聆聽的研究多半集中於「演奏者聆聽已練熟的音樂」,此際,演奏者大腦中部分的 聽覺區與手部運動區會一起活化(Jancke et al., 2000, Haueisen and Knosche, 2001, Popescu et al., 2004, Haslinger et al., 2005, Bangert et al., 2006, D'Ausilio et al., 2006)。 在本研究中,動作與音樂的緊密連結仍然是主動聆聽(而非被動聆聽)的關鍵,但 是,聆聽熟悉音樂之際的內在演練,並不是透過手部的運動,而是口頭的音樂再現。

跟著旋律在心中默唱,是十分普遍的聆聽行為,近年已經有些研究指出了內在 哼唱的神經基礎。Halpern 與 Zatorre (1999) 測量了「想像熟悉旋律」之際的大腦活 化形態,發現右側的聯合聽覺皮質(auditory association cortex)、兩側前運動皮質 (bilateral premotor cortices)、輔

助運動區(supplementary motor area)皆參與這個心智活動。 Hickok 等人(2003)研究旋律及語 音的聆聽與內在唱念,發現左側 聯合聽覺皮質後方的 PT (planum temporale)以及兩側前運動皮質 (dPM; dorsal premotor cortex)的 參與,這些較高階的聽覺區與運 動區,皆屬於聽覺處理的背側路 徑(auditory dorsal stream,也稱 為 dorsal stream for speech

processing),它是將聲響映射至口頭運動的介面(Hickok and Poeppel, 2007) ,參見 圖 1。

大致而言,聽覺處理的背側路徑就是「聽覺鏡像神經元系統」,此系統在音樂 家進行心像練習(mental practice)時也會活化,因為這種心像練習牽涉到聽覺想像 與運動想像。針對聽覺想像的研究發現:初級聽覺皮質並不參與跟想像有關的聽覺 處理,反倒是較高階的聽覺區被活化了(Halpern and Zatorre, 1999)。Lotze 等人(1999) 發現,輔助運動區、前運動皮質於心像練習與實際動作時皆會活化。 在某些情形下,在聆聽器樂時進行口頭演練,可以視為一個處理外在事件的「內 在模型」,聽者以主動而非被動的方式來認知音樂。Schubotz (2007)在闡述「以運動 系統來預測外界事件」時指出,不會彈鋼琴的愛樂者在聆聽鋼琴曲時,腦中的口頭 運動系統可能會活化,以內在哼唱來輔助聆聽。這樣的主動聆聽,建立了由上而下 的期待(top-down expectation),即將出現的音樂事件,在腦中便被限制在少數幾個

可能性裡面(Schubotz, 2007; Schutz-Bosbach and Prinz, 2007; Skipper et al., 2007)。上 述這個觀點,跟許多樂種的聆聽經驗大致吻合,例如有些樂曲是以特定的序列所串 連而成,內在哼唱的序列性質,可以讓主動聆聽者在心中建立起音樂之流,根據先 前的音樂事件預測接下來的音樂。 雖然有關聽覺鏡像神經元系統的研究已經累積了相當的成果,但該系統在「器 樂的口頭再現」中究竟扮演什麼樣的角色,過去並沒有學者作過探討。本研究以京 劇鑼鼓與爵士鼓音樂作為研究材料,探討非專業的京劇愛好者與專業的鼓手,大腦 中整合打擊樂聲音與相關動作(四肢動作或口頭念誦動作)的神經機制。

三、研究方法

「非旋律性打擊音樂的口傳」的研究主題為京劇鑼鼓的口傳,受試者為熟悉京 劇鑼鼓聲響、會念一些鑼鼓經,但沒有演奏過鑼鼓的戲曲愛好者,共計 14 名(其 中兩名的數據因儀器問題而作廢)。「爵士鼓手演練音樂的神經基礎」的研究主題為 爵士鼓點的口傳,受試者為 15 名爵士鼓手,學習打鼓時間超過三年,且至今每周 都練習 3 小時以上。「非旋律性打擊音樂的口傳」實驗之刺激材料有三種,每段刺 激的長度皆為 30 秒:learnPM (意即 learned percussion music):受試者已念熟的京劇鑼鼓演奏 learnPMV (意即 learned percussion music verbalized):learnPM 的念誦版本 learnMM (意即 learned melodic music):受試者已背熟的胡琴旋律

unlearnPM (意即 unlearned percussion music):受試者不熟悉的川劇鑼鼓演奏 「爵士鼓手演練音樂的神經基礎」實驗之刺激材料有三種,每段刺激的長度皆 為 20 秒:

D1-D6:爵士鼓演奏 V1-V6:D1-D6 的念誦版本 R1-R12: 隨機出現的鼓點(每 0.3-1 秒出現一個鼓點) 受試者必須先背熟鼓點與旋律,通過音樂熟悉度測驗之後方能進行大腦掃描。 功能性核磁共振造影實驗進行中,受試者必須躺在大腦掃描儀器中,跟著刺激材料 想像念鼓點、哼旋律,或打鼓。所得到的大腦活化數據以 SPM 軟體進行統計分析。

四、結果

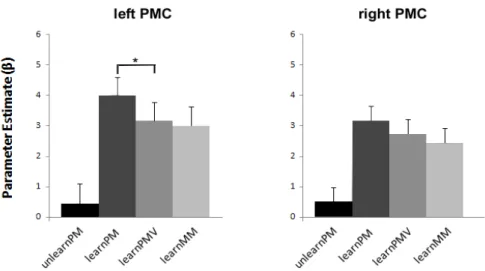

圖 2 顯示了「跟著打擊樂聲響在心中默念」的大腦活化型態(已減去 baseline 「聆聽穩定噪音」的活化),京劇鑼鼓實驗的結果(圖 2A)與爵士鼓實驗的結果(圖 2B)並排顯示。圖 2:所有受試者在「跟著打擊樂聲響在心中默念」的平均活化型態。(A)京劇鑼鼓 實驗的結果,(B)爵士鼓實驗的結果。1: 右腦,2: 左腦,3: 前視圖,4: 俯視圖。 圖 3 比較了京劇鑼鼓實驗中四個狀況的前運動皮質活化強度,可以看到,被動 聆聽不熟悉的川劇鑼鼓(unlearnPM),不會讓兩側的前運動皮質顯著活化,前運動 皮質僅在主動聆聽才會顯著活化。若比較「跟著京劇鑼鼓在心中默念鑼鼓經」 (learnPM)與「跟著鑼鼓經在心中默念鑼鼓經」(learnPMV)這兩個狀況,左側前 運動皮質的活化差異達到顯著(以 * 標出),右側則未達顯著。

圖 3:京劇鑼鼓實驗中四個狀況的前運動皮質活化強度。若比較「跟著京劇鑼鼓在 心中默念鑼鼓經」(learnPM)與「跟著鑼鼓經在心中默念鑼鼓經」(learnPMV)這 兩個狀況,左側前運動皮質的活化差異達到顯著(以 * 標出),右側則未達顯著。 圖 4 顯示在爵士鼓實驗中,「跟著鼓聲在心中默想打鼓」的活化減去「跟著鼓 聲在心中默念鼓點」的活化,得到左側 PT 後上方腦區的活化。

五、討論

音樂的傳承方式主要有兩種。關於音樂傳承中的樂譜認知,近年的神經科學研 究相當豐富,包括大腦功能造影(Schon et al., 2002, Gunter et al., 2003, Schon and Besson, 2005, 2006, Kopiez et al., 2006)與臨床病理探討(Horikoshi et al., 1997,圖 4:爵士鼓實驗中,「跟著鼓聲 在心中默想打鼓」的活化減去 「跟著鼓聲在心中默念鼓點」的 活化,得到左側 PT 後上方的活 化。這三張圖分別是「透明腦」 的側視圖(左上)、後視圖(右 上)、俯視圖(左下)。

Beversdorf and Heilman, 1998, Kawamura et al., 2000, Midorikawa et al., 2003,

McDonald, 2006)。但最早出現的音樂傳承並非透過書寫傳統(written tradition),而

是透過口傳的方式,這方面的神經科學研究還十分欠缺。本研究首度以大腦造影技 術來探討打擊樂的口傳,希望能進一步闡明聽覺背側路徑的功能,以跨文化的比較 來凸顯音樂認知在生物學上的普同性。 筆者在 2007 年夏天開始著手京劇鑼鼓的大腦實驗,歷時一年才完成數據處理。 2009 年 9 月,關於爵士鼓手的大腦造影實驗陸續有結果出現,跟京劇鑼鼓的實驗結 果頗為類似,這個發現令筆者有所感觸。雖然爵士鼓音樂跟京劇鑼鼓聽起來頗不相 同,在目前音樂生態中的使用情形殊異,但是,人腦處理這些音樂的神經迴路卻相 當類似。得到這樣的結果並不意外,然而,這不免讓我想到「音樂與人的關係」在 研究方向上的分歧,不同的取徑可以得到不同的結論。喜歡探討音樂生態的民族音 樂學家與社會音樂學家,著眼於「音樂與人的關係」之外環路徑,應該會發現爵士 鼓音樂跟京劇鑼鼓的差異;反之,認知科學家著眼於「音樂與人的關係」之內部路 徑,理所當然,會發現爵士鼓音樂跟京劇鑼鼓的相似之處。 從圖 2 可以看到,受試者在「跟著打擊樂聲響在心中默念」時,大腦兩側的 dPM 與 PT 都會活化,其中 dPM 是背側的前運動皮質,PT 為聯合聽覺皮質的主體,它 們分別是較高階的運動區與聽覺區。不管是想像演奏或唱念的動作、想像音樂或語 音,這些高階的運動區與聽覺區都會活化,它們構成了聽覺鏡像神經元系統的主 體,許多學者已經指出鏡像神經元系統在模仿時扮演關鍵的角色;音樂的口傳既然 以模仿為主(而非將樂譜上的符號進行轉譯),必然需要聽覺鏡像神經元系統的參 與。 由於代表打擊樂聲響的音節在聲響特質上與原本的打擊樂頗有差距,因此,打 擊樂的口頭再現必須透過「連結學習」(association learning)。先前的神經科學研究 已經指出,左腦的背側前運動皮質在「將外界刺激連結至特定動作」的認知任務中 扮演關鍵性的角色(Zach, et al. 2008)(Amiez et al., 2006; Cavina-Pratesi et al., 2006; Toni et al., 2002)(Halsband and Freund, 1990; Petrides, 1997)(Halsband and Passingham, 1982; Petrides, 1982; Petrides, 1986)(Zatorre et al., 2007),圖 3 顯示左腦背側前運動皮 質在「跟著京劇鑼鼓在心中默念鑼鼓經」時的活化大於「跟著鑼鼓經在心中默念鑼 鼓經」時,與先前的研究結果吻合,因為「跟著鑼鼓經在心中默念鑼鼓經」並不涉 及複雜的連結機制,而「跟著京劇鑼鼓音樂在心中默念鑼鼓經」牽涉到鑼鼓聲響與 念誦動作之間的聯結(stimulus-response association),或負責將聽到的鑼鼓聲響與 心中默念的語音加以整合,此為打擊樂口傳的認知特質。 除了背側前運動皮質之外,位於頭頂心附近的輔助運動區也被認為與「連結學 習」有關。圖 2 顯示「跟著打擊樂聲響在心中默念」的大腦活化型態,輔助運動區 僅在京劇鑼鼓實驗中顯著活化,爵士鼓實驗中並無活化,這或許反映出專家效應 (expertise effect):京劇鑼鼓實驗中的受試者仍在學習階段,因此需要輔助運動區 持續監控與偵錯(Gallea et al., 2008; Klein et al., 2007),反之,爵士鼓實驗中的受試

者都是專家,早已離開學習階段,故不需要輔助運動區的參與。輔助運動區被認為 是「超級鏡像神經元系統」的一環,所謂「超級」,指的是它控管著鏡像神經元系 統的運作,可視為其上級單位。倘若某項音樂認知作業已經練得很熟了,這個上級 單位自然就不太需要操心,由下屬單位獨立完成該作業即可。 以上的解釋中,有個疑點必須稍加留意。京劇鑼鼓實驗的結果與爵士鼓實驗的 結果,其差異不僅來自於受試者的音樂專業性,也來自於這兩種音樂的形式差異。 京劇鑼鼓實驗中所使用的刺激材料,為「起霸」的片段鑼鼓以及「大鑼抽頭轉小鑼 抽頭」;這些配合演員動作的音樂,速度並不固定,節奏可以自由反覆,要跟上這 種音樂的進行,比較需要認知上的監控。反之,爵士鼓音樂作為歌曲的伴奏,是速 度穩定且反覆次數固定的律動(groove),受試者一旦辨識出這是哪個鼓點,就可以 自行完成演練,不需要時時留意音樂刺激。京劇鑼鼓的節奏相對單純,但形式不固 定;爵士鼓音樂的節奏複雜,但形式固定。這或許也造成了京劇鑼鼓實驗中前運動 皮質活化較強,而爵士鼓實驗中右側聽覺皮質活化較強的現象,此現象應該跟樂種 特性有關,不盡然是專家效應的結果。筆者認為,輔助運動區的活化程度比較能反 映生手與熟手的差別,此一推測奠基於過去許多有關學習的研究,包括序列學習 (Alario et al., 2006; Cavina-Pratesi et al., 2006; Kennerley et al., 2004; Nakamura et al., 1998)與節奏學習(Ramnani and Passingham, 2001)。

在爵士鼓實驗中,由於受試者都是專家,所以可以比較「想像演奏鼓點」與「想 像念誦鼓點」的大腦活化差異。圖 4 顯示,「跟著鼓聲在心中默想打鼓」比「跟著 鼓聲在心中默念鼓點」多活化了左側 PT 後上方的腦區,這個發現與過去的一項研 究吻合。Pa 與 Hickok (2008)曾經作過類似的實驗,該實驗以鋼琴家為受試者,讓他 們想像哼唱或想像彈奏一些旋律,發現左側 PT 後上方腦區的活化在想像彈奏時較 強。簡言之,在 PT 附近的聽覺鏡像神經元,與口頭動作有關者,位於前區偏下方; 與四肢動作有關者,位於後區偏上方。

六、結語

器樂的口頭再現,在各個音樂文化中屢見不鮮,除了本文所提到的京劇鑼鼓與 爵士鼓音樂,還有:日本三味線音樂、日本太鼓音樂、印度 tabla 鼓音樂...等。由 大腦造影實驗,可以發現聽覺鏡像神經元系統在「器樂的口頭再現」中所扮演的角 色,以及輔助運動區所反映的專家效應。在台灣,跨領域的大腦研究較為少見,特 別是人文藝術領域的學者與研究生,對於腦科學的實際探索十分缺乏,縱使有興趣 也難以入手。筆者認為,音樂學界與認知神經科學界的交流,除了可以為音樂教育 帶來一些啟示,也有希望在全球激烈競爭的科學研究中,藉著本土音樂素材或「非 西方╱非精英」的觀點,開創出一片藍海。參考資料

Bangert M, Peschel T, Schlaug G, Rotte M, Drescher D, Hinrichs H, Heinze HJ, Altenmuller E (2006) Shared networks for auditory and motor processing in professional pianists: evidence from fMRI conjunction. Neuroimage 30:917-926. Bengtsson SL, Ullen F (2006) Dissociation between melodic and rhythmic processing

during piano performance from musical scores. Neuroimage 30:272-284.

Beversdorf DQ, Heilman KM (1998) Progressive ventral posterior cortical degeneration presenting as alexia for music and words. Neurology 50:657-659.

Brattico E, Tervaniemi M, Naatanen R, Peretz I (2006) Musical scale properties are automatically processed in the human auditory cortex. Brain Res 1117:162-174. Brown S, Martinez MJ (2007) Activation of premotor vocal areas during musical

discrimination. Brain Cogn 63:59-69.

Brown S, Martinez MJ, Hodges DA, Fox PT, Parsons LM (2004) The song system of the human brain. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 20:363-375.

Callan DE, Callan AM, Honda K, Masaki S (2000) Single-sweep EEG analysis of neural processes underlying perception and production of vowels. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 10:173-176.

D'Ausilio A, Altenmuller E, Olivetti Belardinelli M, Lotze M (2006) Cross-modal plasticity of the motor cortex while listening to a rehearsed musical piece. Eur J Neurosci 24:955-958.

Fitch WT (2006) The biology and evolution of music: a comparative perspective. Cognition 100:173-215.

Gallese V, Fadiga L, Fogassi L, Rizzolatti G (1996) Action recognition in the premotor cortex. Brain 119 ( Pt 2):593-609.

Gunji A, Ishii R, Chau W, Kakigi R, Pantev C (2007) Rhythmic brain activities related to singing in humans. Neuroimage 34:426-434.

Gunter TC, Schmidt BH, Besson M (2003) Let's face the music: a behavioral and electrophysiological exploration of score reading. Psychophysiology 40:742-751. Halpern AR, Zatorre RJ (1999) When that tune runs through your head: a PET

investigation of auditory imagery for familiar melodies. Cereb Cortex 9:697-704. Haslinger B, Erhard P, Altenmuller E, Schroeder U, Boecker H, Ceballos-Baumann AO

(2005) Transmodal sensorimotor networks during action observation in professional pianists. J Cogn Neurosci 17:282-293.

Haueisen J, Knosche TR (2001) Involuntary motor activity in pianists evoked by music perception. J Cogn Neurosci 13:786-792.

Hickok G, Buchsbaum B, Humphries C, Muftuler T (2003) Auditory-motor interaction revealed by fMRI: speech, music, and working memory in area Spt. J Cogn Neurosci 15:673-682.

Hickok G, Poeppel D (2007) The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:393-402.

Horikoshi T, Asari Y, Watanabe A, Nagaseki Y, Nukui H, Sasaki H, Komiya K (1997) Music alexia in a patient with mild pure alexia: disturbed visual perception of nonverbal meaningful figures. Cortex 33:187-194.

Itoh K, Suwazono S, Nakada T (2003) Cortical processing of musical consonance: an evoked potential study. Neuroreport 14:2303-2306.

Jancke L, Shah NJ, Peters M (2000) Cortical activations in primary and secondary motor areas for complex bimanual movements in professional pianists. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 10:177-183.

Kawamura M, Midorikawa A, Kezuka M (2000) Cerebral localization of the center for reading and writing music. Neuroreport 11:3299-3303.

Kleberg A, Westrup B, Stjernqvist K (2000) Developmental outcome, child behaviour and mother-child interaction at 3 years of age following Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Intervention Program (NIDCAP) intervention. Early Hum Dev 60:123-135.

Klein D, Zatorre RJ, Milner B, Meyer E, Evans AC (1994) Left putaminal activation when speaking a second language: evidence from PET. Neuroreport 5:2295-2297. Koelsch S (2005) Neural substrates of processing syntax and semantics in music. Curr

Opin Neurobiol 15:207-212.

Koelsch S (2006) Significance of Broca's area and ventral premotor cortex for music-syntactic processing. Cortex 42:518-520.

Koelsch S, Fritz T, Schulze K, Alsop D, Schlaug G (2005) Adults and children processing music: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 25:1068-1076.

Koelsch S, Jentschke S (2008) Short-term effects of processing musical syntax: an ERP study. Brain Res 1212:55-62.

Koelsch S, Jentschke S, Sammler D, Mietchen D (2007) Untangling syntactic and sensory processing: an ERP study of music perception. Psychophysiology 44:476-490.

Kohler E, Keysers C, Umilta MA, Fogassi L, Gallese V, Rizzolatti G (2002) Hearing sounds, understanding actions: action representation in mirror neurons. Science 297:846-848.

Kopiez R, Galley N, Lee JI (2006) The advantage of a decreasing right-hand superiority: the influence of laterality on a selected musical skill (sight reading achievement). Neuropsychologia 44:1079-1087.

Kuriki S, Isahai N, Ohtsuka A (2005) Spatiotemporal characteristics of the neural activities processing consonant/dissonant tones in melody. Exp Brain Res

162:46-55.

Lotze M, Montoya P, Erb M, Hulsmann E, Flor H, Klose U, Birbaumer N, Grodd W (1999) Activation of cortical and cerebellar motor areas during executed and imagined hand movements: an fMRI study. J Cogn Neurosci 11:491-501.

Loui P, Grent-'t-Jong T, Torpey D, Woldorff M (2005) Effects of attention on the neural processing of harmonic syntax in Western music. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 25:678-687.

Maeshima K, Shiba R, Nemoto I (2007) Comparison of mismatch fields elicited by changes in tonal and atonal sequences. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2007:2504-2507.

Maess B, Koelsch S, Gunter TC, Friederici AD (2001) Musical syntax is processed in Broca's area: an MEG study. Nat Neurosci 4:540-545.

McDonald I (2006) Musical alexia with recovery: a personal account. Brain 129:2554-2561.

Midorikawa A, Kawamura M, Kezuka M (2003) Musical alexia for rhythm notation: a discrepancy between pitch and rhythm. Neurocase 9:232-238.

Minati L, Rosazza C, D'Incerti L, Pietrocini E, Valentini L, Scaioli V, Loveday C, Bruzzone MG (2008) FMRI/ERP of musical syntax: comparison of melodies and unstructured note sequences. Neuroreport 19:1381-1385.

Munte TF, Altenmuller E, Jancke L (2002) The musician's brain as a model of neuroplasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci 3:473-478.

Neuhaus C (2003) Perceiving musical scale structures. A cross-cultural event-related brain potentials study. Ann N Y Acad Sci 999:184-188.

Ozdemir E, Norton A, Schlaug G (2006) Shared and distinct neural correlates of singing and speaking. Neuroimage 33:628-635.

Patterson RD, Uppenkamp S, Johnsrude IS, Griffiths TD (2002) The processing of temporal pitch and melody information in auditory cortex. Neuron 36:767-776. Perry DW, Zatorre RJ, Petrides M, Alivisatos B, Meyer E, Evans AC (1999) Localization

of cerebral activity during simple singing. Neuroreport 10:3979-3984.

Popescu M, Otsuka A, Ioannides AA (2004) Dynamics of brain activity in motor and frontal cortical areas during music listening: a magnetoencephalographic study. Neuroimage 21:1622-1638.

Poulin-Charronnat B, Bigand E, Koelsch S (2006) Processing of musical syntax tonic versus subdominant: an event-related potential study. J Cogn Neurosci 18:1545-1554.

Ramnani N, Passingham RE (2001) Changes in the human brain during rhythm learning. J Cogn Neurosci 13:952-966.

Rizzolatti G, Fadiga L, Gallese V, Fogassi L (1996) Premotor cortex and the recognition of motor actions. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 3:131-141.

Ruiz MH, Koelsch S, Bhattacharya J (2008) Decrease in early right alpha band phase synchronization and late gamma band oscillations in processing syntax in music. Hum Brain Mapp.

Schon D, Anton JL, Roth M, Besson M (2002) An fMRI study of music sight-reading. Neuroreport 13:2285-2289.

Schon D, Besson M (2005) Visually induced auditory expectancy in music reading: a behavioral and electrophysiological study. J Cogn Neurosci 17:694-705.

Schubotz RI (2007) Prediction of external events with our motor system: towards a new framework. Trends Cogn Sci 11:211-218.

Steinbeis N, Koelsch S (2008) Shared neural resources between music and language indicate semantic processing of musical tension-resolution patterns. Cereb Cortex 18:1169-1178.

Steinbeis N, Koelsch S, Sloboda JA (2005) Emotional processing of harmonic expectancy violations. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1060:457-461.

Steinbeis N, Koelsch S, Sloboda JA (2006) The role of harmonic expectancy violations in musical emotions: evidence from subjective, physiological, and neural responses. J Cogn Neurosci 18:1380-1393.

Tervaniemi M, Hugdahl K (2003) Lateralization of auditory-cortex functions. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 43:231-246.

Trainor LJ, McDonald KL, Alain C (2002) Automatic and controlled processing of melodic contour and interval information measured by electrical brain activity. J Cogn Neurosci 14:430-442.

Tsai CG, Chen CC, Chou TL, Chen JH (2010) Neural mechanisms involved in the oral representation of percussion music: an fMRI study. Brain Cogn 74:123-131. Zarate JM, Zatorre RJ (2008) Experience-dependent neural substrates involved in vocal

pitch regulation during singing. Neuroimage 40:1871-1887.

Zatorre RJ, Chen JL, Penhune VB (2007) When the brain plays music: auditory-motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:547-558. Zatorre RJ, Perry DW, Beckett CA, Westbury CF, Evans AC (1998) Functional anatomy

of musical processing in listeners with absolute pitch and relative pitch. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:3172-3177.