ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Effects of educational intervention on nurses

’ knowledge,

attitudes, and behavioral intentions toward supplying

artificial nutrition and hydration to terminal cancer patients

Li-Shan Ke&Tai-Yuan Chiu&Wen-Yu Hu&Su-Shun LoReceived: 2 November 2007 / Accepted: 13 February 2008 / Published online: 12 March 2008

# Springer-Verlag 2008 Abstract

Introduction This study aimed to investigate the effects of educational intervention on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions regarding supplying artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) to terminal cancer patients. Materials and methods A quasi-experimental design was adopted. A structured questionnaire evaluated the effects of educational intervention. From April to June 2005, 88 nurses

were enrolled in the gastroenterology, general surgery, and intensive care unit of Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan. The nurses were randomly assigned into experimen-tal and control groups in equal numbers (44 nurses in each group). After the experimental and control groups completed the pretest, the experimental group participated in a 50-min lecture. Both groups received a post-test 2 weeks after the lecture.

Results This study showed that prior to educational interven-tion, nurses have possessed experiences of ANH use in routine caring for terminal cancer patients. However, due to the lack of knowledge about supplying ANH to terminal cancer patients, the nurses trended toward the negative behavioral intention, although they realized the burdens of ANH in these patients. After educational intervention, mean scores of knowledge, attitudes and behavioral intentions of the experimental group increased significantly (z=−5.255, p<0.001; t=−5.191, p<0.001; z=−3.274, p≦0.001). Mean score changes of knowledge and attitude between these two groups reached significant differences (t=−7.306, p<0.001; t=−4.165, p<0.001), but no significant difference was observed in the mean score change of behavioral intention (z=−1.943, p>0.05).

Conclusion The educational intervention remarkably im-proved nurses’ knowledge and attitudes regarding supply-ing terminal cancer patients with ANH. As for the changes in the behavioral intentions, it requires long-term moral and ethical training and communication. The results of this research emphasized the importance of educational inter-ventions, which should be considered seriously in future reference nursing education program.

Keywords Artificial nutrition and hydration . Terminal cancer patients . Knowledge . Attitudes . Behavioral intentions

L.-S. Ke

Department of Nursing, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

T.-Y. Chiu

College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

T.-Y. Chiu

Department of Family Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

W.-Y. Hu (*)

School of Nursing, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University,

1 Ren-Ai Rd Sect. 1, Jhongjheng District, Taipei 100, Taiwan

e-mail: weyuhu@ntu.edu.tw W.-Y. Hu

Department of Nursing, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

S.-S. Lo

College of Medicine, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan

S.-S. Lo

Department of Surgery, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

Introduction

Cancer leads the top ten causes of death in Taiwan. In 2006, 37,998 individuals died from cancer, an incidence of 166.5 per 100,000 population, reflecting 28.1% of total deaths [8]. Until 2003, there were only 418 beds in the palliative care units (PCUs) within the nation. According to Dr. Y. L. Lai, only 16.3% of patients who died from cancer received care from PCUs [14]. This phenomenon indicates that PCUs are not sufficiently available in Taiwan. In other words, the majority of terminal cancer patients are treated in non-palliative care units. Our research has shown that 96.9% of nurses in the gastroenterology (GI), general surgery (GS), and intensive care unit (ICU) have had experience caring for terminal cancer patients, emphasizing the universality of non-palliative care for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan [13]. In modern medicine, the level and quality of care that terminally ill patients receive in PCUs are dramatically different from care received in other units. The PCU focuses on the physical and spiritual comfort of patients, as well as providing attentive care to families. Non-palliative care units, however, place more emphasis on treatment of disease at different stages and other existing health concerns. Therefore, misplacement of terminal cancer patients in non-palliative care units can actually expose patients to non-beneficial or even harmful treatment measures, with artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) as a prime example. Normally, it is recognized that ANH can provide advantages such as prolonging life and enhancing patients’ physical strength. Some studies suggested that dehydration may contribute to an agitated delirium or terminal restlessness that could be eased by gentle hydra-tion [3,10,11].

Sensation of thirst is a frequent symptom in terminal cancer patients and is associated with dehydration. Morita’s study showed that no significant correlations were observed between the visual analogue scale score for thirst and the laboratory tests, which defined biochemical dehydration, such as total protein, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, sodium, osmolality, hematocrit, and atrial natriuretic pep-tide [21]. Ellershaw’s study showed no statistical

signifi-cance between the level of hydration and the symptoms form dehydration [9]. Moreover, no evidence that suggested that aggressive nutrition therapy can improve the quality of life. Chiu’s study showed that ANH has no significant influence on survival [7]. However, an increasing number of literature reviews have suggested that ANH is a futile treatment and even brings more harm than good to terminal cancer patients, such as inducing anasarca or pulmonary edema [4,6,18,20,23,25]. Zerwekh, a PCU nurse, first realized this in 1983 and published a paper on the disadvantages of ANH and the possible advantages of dehydration in terminally ill patients based on her clinical

experience [33]. In 1988, Printz proved that β-endorphin secretions can be enhanced by starvation in an experiment with a rat model [26]. In 1989, Andrews and Levine reported a study focusing on PCU nurses that showed 71% of the nurses agreed that reduction of fluid intake can reduce vomiting, 51% agreed that discontinuation of providing fluid can alleviate the sense of choking and suffocation, and 53% agreed that terminal dehydration was beneficial to terminally ill patients [1]. It was not until recently that case studies showed that patients passed away peacefully without ANH or from the withdrawal of ANH [27]. Despite these facts, this concept is still relatively unacceptable to the medical professional. Research has shown that medical professionals are biased toward providing ANH [2,17, 19,28]. Chiu et al. have indicated that the medical professional plays an important role in influencing patients and families about the use of ANH [6]. Nevertheless, our study has shown that nurses lack general knowledge of ANH, resulting in the tendency to provide ANH to terminal cancer patients [13]. This phenomenon led us to conduct research about the educational interven-tion to non-palliative care unit nurses regarding supplying ANH to terminal cancer patients. Results of this research may reinforce the need to enhance nurses’ knowledge and modify their attitudes and behavioral intentions, subse-quently providing appropriate knowledge and aiding med-ical decisions made by patients and their families.

Materials and methods Subjects

A quasi-experimental design was adopted. A structured questionnaire evaluated the effects of educational interven-tion. From April to June 2005, 88 nurses were enrolled in the GI, GS, and ICU of Taipei Veterans General Hospital in Taiwan. These nurses were randomly assigned into exper-imental and control groups in equal numbers. Before the study was conducted, the research plan was presented to an Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital where the study was to take place. After evaluation and approval, the study was formally initiated. Measurements

The structured questionnaire includes the following four parts: demographic characteristics, knowledge of providing ANH to terminal cancer patients (15 items), attitudes (17 items), and behavioral intentions (two items). Demographic characteristics included gender, age, education, and experi-ence in caring for terminal cancer patients, experiexperi-ence with ANH given to terminal cancer patients cared in the past

year, and perceptions of physical and psychological comfort level of terminal cancer patients in receiving ANH (the scale was 1–10 points from very uncomfortable to very comfortable). The first draft of the questionnaire was evaluated by expert opinion of four doctors and two nurses, with a content validity index of 0.93. The validity and reliability of other parts were presented as follows: 1. Knowledge of providing ANH to terminal cancer

patients. The content includes goals of ANH treatment, metabolic mechanism and nutritional supply in terminal cancer patients, and relationships between dehydration, hunger, and comfort in terminally ill patients. The scoring system of this scale was“true (1)” and “false/ unknown (0)”. Higher scores would, therefore, reflect greater knowledge of provision of ANH to terminal cancer patients among the nurses assessed. The content and consistency of items were generally acceptable, with a Kuder–Richardson formula 20 value of 0.67. 2. Attitudes toward behavior (AB). This part examined the

perception of nurses regarding the advantages and disadvantages of providing ANH for terminal cancer patients. This is divided into two categories, belief (Bi) and evaluation (Ei). The measure was 17 items using 5-point Likert scales from “strongly disagree/very unim-portant (1)” to “strongly agree/very imunim-portant (5).” Regarding advantages of ANH, reverse scoring was employed. Higher total mean score of attitude (AB = ΣBi × Ei) indicates the more appropriate attitude towards not supplying ANH to terminal cancer patients. The scores in attitude (AB) ranged from 1 to 25 points. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity (BT) and Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test were administered resulting in a BT value of 604.94 (statistical significance=0.000) and a KMO value of 0.68, indicating that exploratory factor analysis may be warranted. The principal component analysis, followed by orthogonal varimax rotation, was then employed to carry out construct validity, with a loading value of 0.4 as a cut point. The last two extracted factors were named “benefits of providing ANH” (eight items) and “burdens of providing ANH” (nine items). Cronbach’s α for these factors were respectively 0.79 and 0.85, showing that items contained in each factor could be used to test the same characteristic. Cronbach’s α for the overall ques-tionnaire was 0.72.

3. Behavioral intentions. This section presented the scenario of a terminal cancer patient facing ANH and subsequently assessing tendencies of the nurses to give or withhold the treatment. The 4-point Likert scales was adopted. Based on the hypothesis of this research, the positive behavioral intentions tended toward with-holding ANH to terminal cancer patients. The criteria were established as follows: “very unlikely (4),”

“unlikely (3)”, “likely (2)”, and “very likely (1).” Cronbach’s α for two items was 0.67.

Data collection

After the experimental and control groups completed the pretest, only the experimental group participated in a 50-min lecture. Both groups received a post-test 2 weeks after the experimental group ending of the lecture. We compiled the educational portfolio“Critical thinking of providing artificial nutrition and hydration in terminal cancer patients” through massive and rigorous literature review. The portfolio includes handouts and power-point presentations. The difficulty level of the content was assessed by three clinical nurses and determined to be interpretable. The formatting, color, anima-tion, and configuration of the power-point presentation were produced with guidance from a nurse and an instructor who were all familiar with the computer. A 50-min lecture with slide presentation and handouts was given by the principal investigator. The contents included normal nutrient metabo-lism (7 min), nutrient metabometabo-lism for terminal cancer patients (13 min), and the appropriateness of supplying terminal cancer patients with ANH concerning the benefits and burdens of providing ANH in these patients (30 min). Statistical analysis

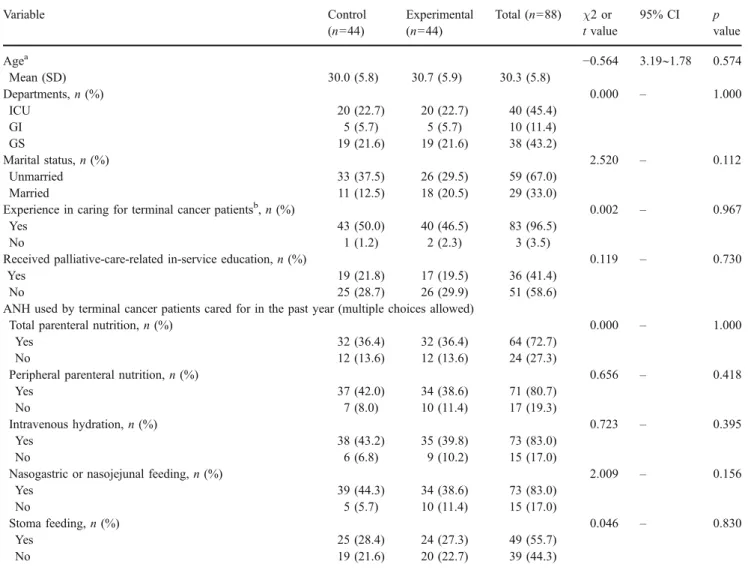

SPSS 11.0 statistics software package was used for data entry and analysis. A p value of <0.05 was defined as statistical significance. Chi-square and Yates’ tests examine the ho-mogeneity of the nominal variables and the independent sample t test analyzes homogeneity of continuous variables in the demographic characteristics of experimental and con-trol groups. Normal distribution of the sample was examined with Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The sample, which was non-normal distribution, adopted nonparametric tests includ-ing Mann–Whitney (M–W) test and Wilcoxon signed ranks test. Before the educational intervention, the nurses’ knowl-edge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions were tested for homogeneity. However, prior to educational intervention, no statistically significant differences were shown between the two groups in demographic characteristics, knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions (Tables1and2).

Results

Overall profile before educational intervention

Both control and experimental groups were highly homog-enous, and, therefore, we discuss their information together. Nurses were all females with a mean age of 30.3, and 67%

of them were unmarried. Among all nurses, 83 out of 88 (96.5%) had previous experience with terminal cancer patients care, but 58.6% had never received palliative-care-related in-service education. In nurses’ experiences of giving ANH to terminal cancer patients in the past year, 80.7% were peripheral parenteral nutrition, 83.0% were intravenous hydration, 83.0% were nasogastric or nasoje-junal feeding, and 72.7% were total parenteral nutrition (Table1). In addition, 78.5% of nurses had been requested

by the terminal cancer patients to give nutritional support, and 93.1% of nurses had been requested by the family of terminal cancer patients to give nutritional support. The physical comfort level of terminal cancer patients in receiving ANH was perceived to be 4.95 (SD =1.45, range 1–10) by the nurses; the psychological comfort level was perceived to be 6.20 (SD=1.65, range 1–10).

Regarding knowledge of provision of ANH for terminal cancer patients, the mean score among nurses was 6.24

Table 2 Homogeneity of knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions of 2 groups

Variable Control (n=44) Experimental (n=44) t value or z value 95% CI p value

Knowledgea, mean (SD) 5.68 (2.62) 6.80 (3.11) z=−1.694 – 0.090

Attitudes, mean (SD) 10.49 (1.61) 10.65 (2.03) t=−0.404 −0.94∼0.62 0.687

Behavioral intentionsa, mean (SD) 1.58 (0.44) 1.67 (0.42) z=−0.886 – 0.376

a

Used M–W test

Table 1 Homogeneity of demographic characteristics

Variable Control (n=44) Experimental (n=44) Total (n=88) χ2 or t value 95% CI p value Agea −0.564 3.19∼1.78 0.574 Mean (SD) 30.0 (5.8) 30.7 (5.9) 30.3 (5.8) Departments, n (%) 0.000 – 1.000 ICU 20 (22.7) 20 (22.7) 40 (45.4) GI 5 (5.7) 5 (5.7) 10 (11.4) GS 19 (21.6) 19 (21.6) 38 (43.2) Marital status, n (%) 2.520 – 0.112 Unmarried 33 (37.5) 26 (29.5) 59 (67.0) Married 11 (12.5) 18 (20.5) 29 (33.0)

Experience in caring for terminal cancer patientsb, n (%) 0.002 – 0.967

Yes 43 (50.0) 40 (46.5) 83 (96.5)

No 1 (1.2) 2 (2.3) 3 (3.5)

Received palliative-care-related in-service education, n (%) 0.119 – 0.730

Yes 19 (21.8) 17 (19.5) 36 (41.4)

No 25 (28.7) 26 (29.9) 51 (58.6)

ANH used by terminal cancer patients cared for in the past year (multiple choices allowed)

Total parenteral nutrition, n (%) 0.000 – 1.000

Yes 32 (36.4) 32 (36.4) 64 (72.7)

No 12 (13.6) 12 (13.6) 24 (27.3)

Peripheral parenteral nutrition, n (%) 0.656 – 0.418

Yes 37 (42.0) 34 (38.6) 71 (80.7)

No 7 (8.0) 10 (11.4) 17 (19.3)

Intravenous hydration, n (%) 0.723 – 0.395

Yes 38 (43.2) 35 (39.8) 73 (83.0)

No 6 (6.8) 9 (10.2) 15 (17.0)

Nasogastric or nasojejunal feeding, n (%) 2.009 – 0.156

Yes 39 (44.3) 34 (38.6) 73 (83.0) No 5 (5.7) 10 (11.4) 15 (17.0) Stoma feeding, n (%) 0.046 – 0.830 Yes 25 (28.4) 24 (27.3) 49 (55.7) No 19 (21.6) 20 (22.7) 39 (44.3) a

Used independent sample t test

(SD=2.91, range 0–15), with an accurate answer rate of 41.6%. Only two items had an accurate answer rate above 60%; these items were“artificial nutrition replacement can improve hunger status in all terminally ill patients” (69.3%), and“artificial hydration can improve the sensation of mouth dryness and thirst in all terminally ill patients” (61.4%). On the other hand, the two items with the lowest accurate answer rate were “ketoacidosis as a consequence of aphagia often results in an increase of physical pain in terminally ill patients” (9.1%) and “in terminal cancer patients, chronic starvation results in lipolysis, with subsequent ketoacidosis and anorexia, therefore, nutritional support such as nasogastric feeding should be provided in order to improve malnutrition resulting from anorexia” (17.0%). Attitude toward supplying terminal cancer patients with ANH had a mean score of 10.57 (SD=1.91, range 1– 25), which shows the negative attitude of nurses toward being inclined to supply ANH to terminal cancer patients. In benefits of ANH, a mean score of 6.31 (SD=2.13) was obtained. The highest mean score was“ANH can prolong the life of terminally ill patients (10.58),” indicating that nurses seemed to disagree that ANH prolonged the life of terminally ill patients. In burdens of ANH, a mean score of 14.46 (SD =3.30) was obtained, indicating that nurses were aware of various disadvantages of ANH. Among all disadvantages, three received higher scores:“placement of invasive catheters increases the risk of infection in

terminally ill patients (16.14),” “in terminally ill patients, fluid overload is likely to result in pleural effusion, pulmonary edema (15.87),” “fluid overload, such as ascites and peripheral edema, can occur in terminally ill patients receiving intravenous infusions (15.64).” The mean score of the behavioral intention to supply terminal cancer patients with ANH was 1.63 (SD = 0.43, range 1–4), indicating that nurses had a tendency to give ANH to terminal cancer patients. Regarding supplying terminal cancer patients with artificial hydration, 100% of the nurses said either “likely” (59.1%) or “very likely” (40.9%). Regarding supplying terminal cancer patients with artificial nutrition, 98.8% of the nurses said either “likely” (63.6%) or“very likely” (35.2%).

Outcomes of educational intervention

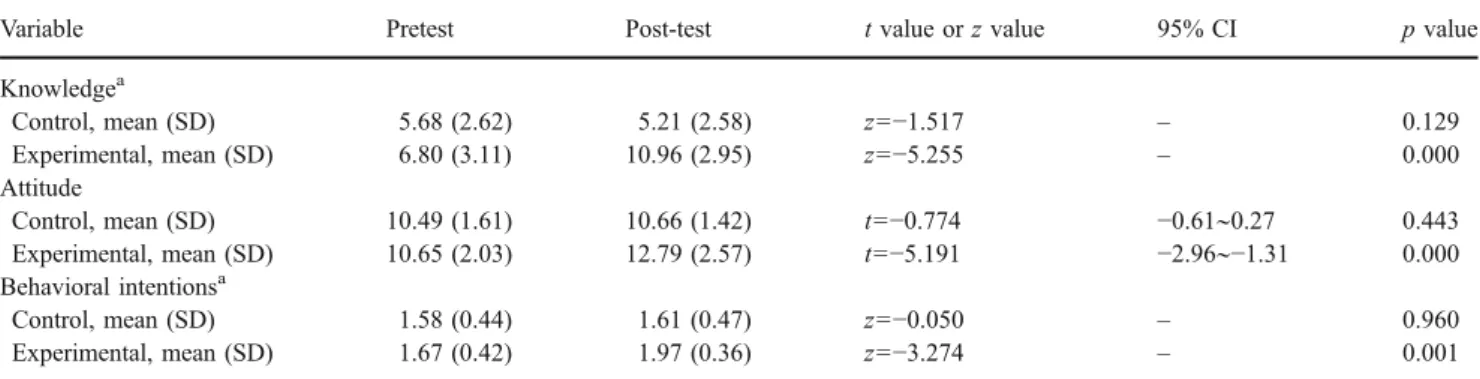

Knowledge of ANH for terminal cancer patients After educational intervention, the mean score of knowledge had significantly increased. Table3 shows that the control group had pretest and post-test mean scores of 5.68 and 5.21, respectively, and the experimental group had pretest and post-test mean scores of 6.80 and 10.96, respectively. While the mean score for the experimental group was significantly higher after the educational intervention (z=−5.255, p<0.001), the control group had no significant differences (p>0.05). Furthermore, the mean score change Table 3 Comparison of mean scores of pretest and post-test within single group

Variable Pretest Post-test t value or z value 95% CI p value

Knowledgea Control, mean (SD) 5.68 (2.62) 5.21 (2.58) z=−1.517 – 0.129 Experimental, mean (SD) 6.80 (3.11) 10.96 (2.95) z=−5.255 – 0.000 Attitude Control, mean (SD) 10.49 (1.61) 10.66 (1.42) t=−0.774 −0.61∼0.27 0.443 Experimental, mean (SD) 10.65 (2.03) 12.79 (2.57) t=−5.191 −2.96∼−1.31 0.000 Behavioral intentionsa Control, mean (SD) 1.58 (0.44) 1.61 (0.47) z=−0.050 – 0.960 Experimental, mean (SD) 1.67 (0.42) 1.97 (0.36) z=−3.274 – 0.001 a

Used Wilcoxon signed ranks test

Table 4 Comparison of mean score changes in 2 groups

Variable Control (n=44) Experimental (n=44) t value and z value 95% CI p value

Knowledge

Mean score change (SD) −0.48 (2.72) 4.18 (3.24) t=−7.306 −5.92∼−3.39 0.000

Attitudes

Mean score change (SD) 0.18 (1.44) 1.86 (2.25) t=−4.165 −2.48∼−0.87 0.000

Behavioral intentionsa

Mean score change (SD) 0.03 (0.56) 0.30 (0.52) z=−1.943 – 0.052

Mean score change = (mean score of post-test)− (mean score of pretest)

a

of knowledge of the experimental group was higher than the control group (t=−7.306, p<0.001; Table 4). This represents the increase in knowledge of ANH for terminal cancer patients after educational intervention.

Attitude towards supplying terminal cancer patients with ANH After educational intervention, the attitude of nurses regarding provision of ANH to terminal cancer patients significantly increased. Table 3 shows that the control group had pretest and post-test mean scores of 10.49 and 10.66, respectively, and the experimental group had pretest and post-test mean scores of 10.65 and 12.79, respectively. The experimental group had a much higher mean score after the educational intervention as compared to the mean score of pretest (t=−5.191, p<0.001); the control group had no significant difference (p>0.05). Additionally, the mean score change of attitude of the experimental group was higher than that of the control group (t=−4.165, p<0.001; Table 4), indicating a more positive trend in attitude towards supplying ANH to terminal cancer patients after educational intervention.

Behavioral intentions toward supplying terminal cancer patients with ANH After educational intervention, nurses showed an improvement of mean score for behavioral intentions. Table 3 shows that the mean scores of pretest and post-test were 1.58 and 1.61, respectively, for the control group and were 1.67 and 1.97, respectively, for the experimental group. The post-test mean score for the experimental group was higher than pretest (z=−3.274, p≦0.001), and no significant difference was observed for the control group (p>0.05). The mean score changes of behavioral intentions in both groups were not significant (z=−1.943, p>0.05; Table4).

Discussion

Among all nurse subjects, 96.5% had experience caring for terminal cancer patients. Among patients being cared for in the past year, over 80% had received peripheral parenteral nutrition, intravenous hydration, and nasogastric or nasoje-junal feeding, and more than 70% of patients had received total parenteral nutrition. This indicates that nurse subjects had abundant experience prior to this research. However, research results show that nurses seemed to disagree that ANH benefits in prolonging life of the terminal cancer patients. Instead, they are concerned about the known burdens of ANH, especially that infection rates increased with the use of invasive catheters for terminal cancer patients and that anasarca or pulmonary edema, ascites, and peripheral edema are induced by excessive fluid. This

demonstrates that nurses seem to realize the disadvantages and inappropriateness of giving ANH to terminal cancer patients, which could be due to their accumulation of direct care and clinical experience with terminal cancer patients. Despite possessing experience in caring for terminal cancer patients, the lack of scientific and evidence-based knowl-edge towards ANH resulted in a tendency for nurses to continue to supply ANH for these patients. Wurzbach has argued that knowledge deeply influences the clarity of ethics and moral decisions [32]. Thus, sufficient knowledge is a crucial element in making ethical decisions. Domestic research has shown that internship and palliative care classes can dramatically increase the knowledge of pallia-tive care for medical students. However, the concept of not supplying ANH to terminally ill patients was hard for medical students to accept despite their attendance in classes [5, 30]. The same effects have been observed among nursing students; palliative care knowledge did not influence their ethical agreement toward withholding ANH for terminal patients [12]. Therefore, aside from clinical experience with palliative care, specialized knowledge towards providing ANH to terminal cancer patients is also necessary. Our educational intervention has produced overall changes in the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions of nurses regarding supplying ANH to terminal cancer patients. However, mean score changes of the behavioral intention between two groups were not signif-icant. We infer that it can be related to the difference in food culture and family culture within Taiwanese society. “Food comes first for people”, “eating is as important as the emperor”, and “having food is lucky” is the food culture of Taiwan for a long time. This culture has been subcon-sciously affecting the Taiwanese. To nurses of Taiwan, they generally assume that “providing ways to eat is the most fundamental care to terminal cancer patients.” The idea is similar to the Japanese doctors’ belief of “intravenous nutrient being the fundamental care” [19] or the American medical students’ belief that “nutrients and hydration are the minimal comfort to patients” [31]. Taiwanese families believe that “requesting nutritional supports for patients is their obligations”, and patients believe that “accepting nutritional supports is the responsibility of being a good patient”. In addition, a Taiwanese tradition of “not becoming a starving soul after death and affecting one’s later generations” often leads to families requiring that ANH be administered by the medical professionals [7]. When this happens, the medical professionals almost always cooperate with the request. In the research, 100% and 98.8% of nurses would be providing artificial hydration and artificial nutrition, respectively. This represents the major effect of Taiwanese culture on supplying ANH to terminal cancer patients. Although nurses can accept the fact that ANH has disadvantages that may make patients physically

uncom-fortable, they claim that ANH has a mentally comforting effect, which appears to concur with scholars who indicate that ANH increases mental support and social significance to the patient [2, 15,16]. Moreover, affected by familism and paternalism in Chinese culture, families and parents dictate over individuals, therefore, stripping patients of their autonomy [29]. In this research, nurses suggested that when supplying ANH, one should especially consider the autonomy of the patient. However, the patient often loses his or her right to make the decision in a society where the family is the primary decision-making unit. In our research, 93.1% of nurses have encountered the situation where families of terminal cancer patient make the request to use nutritional support. This is similar with Japan, which also shares the oriental culture where families participate in more than 90% of the decision making regarding adminis-tering ANH to terminal cancer patients [22]. It is different from the study of Israeli where family’s involvement in decision-making process to intravenous therapy is only 13% [24]. This demonstrates the strong influence of families in the medical decision process for terminal cancer patients in oriental culture.

Conclusion

The experimental group showed significant improvement in mean scores of knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions towards ANH to terminal cancer patients. Furthermore, mean score changes in “knowledge” and “attitude” between experimental and control groups were statistically significant, indicating the efficacy of educa-tional intervention. However, mean scores of changes of behavioral intentions between two groups were not signif-icant; reflecting that the behavioral intentions of nurses are also affected by other variables. These variables may include the ethics and morality of the Taiwanese culture and the powerful role of families. We recommend integrat-ing these additional topics into school and in-service education in order to devise long-term training schemes and domestic guidelines.

Acknowledgments The authors thank the nurses of gastroenterolo-gy, general surgery, and intensive care unit of Taipei Veterans General Hospital for their full support.

References

1. Andrews MR, Levine AM (1989) Dehydration in the terminal patient: perception of hospice nurses. Am J Hosp Care 6:31–34 2. Asch DA, Christakis NA (1996) What do physicians prefer to

withdraw some forms of life support over others? Intrinsic

attributes of life-sustaining treatments are associated with physi-cians’ preferences. Med Care 34:103–111

3. Bruera E, Franco JJ, Maltoni M, Watanabe S, Suarez-Almazor M (1995) Changing pattern of agitated impaired mental status in patients with advanced cancer: association with cognitive moni-toring, hydration, and opioid rotation. J Pain Symptom Manage 10:287–291

4. Burge FI, King DB, Willison D (1990) Intravenous fluids and the hospitalized dying: a medical last rite? Can Fam Physician 36:883–886

5. Chang HH, Hu WY, Chiu TY et al (2003) An interventional study assessing palliative care learning amongst junior medical students undertaking the course“the human side of medicine”. J Med Educ 7:150–160

6. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chuang RB et al (2004) Terminal cancer patients’ wishes and influencing factors toward the provision of artificial nutrition and hydration in Taiwan. J Pain Symptom Manage 27:206–214

7. Chiu TY, Hu WY, Chuang RB, Chen CY (2002) Nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. Support Care Cancer 10:630–636

8. Department of Health, Executive Yuan, Taiwan, R.O.C. 2006 Statistical summary of the main causes of death in Taiwan. Available athttp://www.doh.gov.tw/statistic/index.htm. Accessed Sep 23, 2007

9. Ellershaw JE, Sutcliffe JM, Saunders CM (1995) Dehydration and the dying patient. J Pain Symptom Manage 10:192–197 10. Fainsinger R, Miller MJ, Bruera E, Hanson J, Maceachern T

(1991) Symptom control during the last week of life on a palliative care unit. J Palliat Care 7:5–11

11. Fainsinger RL, Bruera E (1997) When to treat dehydration in a terminally ill patient? Support Care Cancer 5:205–211

12. Hu WY, Tseng CN, Wang Y, Ueng RS (2004) The effects of clinical practice program toward palliative care for nursing students’ education in school of nursing. Taiwan J Hosp Palliat Care 9:1–20

13. Ke LS, Chiu TY, Lo SS, Hu WY (2007) Knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions of nurses toward providing artificial nutrition and hydration for terminal cancer patients in Taiwan. Cancer Nurs 31:67–76

14. Lai YL (2004) Hospice palliative care in Taiwan. Formosan J Med 8:653–656

15. Lynn J, Childress JF (1983) Must patients always be given food and water? Hastings Cent Rep 13:17–21

16. Mc Inerney F (1992) Provision of food and fluids in terminal care: a sociological analysis. Soc Sci Med 34:1271–1276

17. Micetich KC, Steinecker PH, Thomasma DC (1983) Are intravenous fluids morally required for a dying patient? Arch Intern Med 143:975–978

18. Morita T, Hyodo I, Yoshimi T et al (2005) Association between hydration volume and symptoms in terminally ill cancer patients with abdominal malignancies. Ann Oncol 16:640–647

19. Morita T, Shima Y, Adachi I (2002) Attitudes of Japanese physicians toward terminal dehydration: a nationwide survey. J Clin Oncol 20:4699–4704

20. Morita T, Tei Y, Inoue S, Suga A, Chihara S (2002) Fluid status of terminally ill cancer patients with intestinal obstruction: an exploratory observational study. Support Care Cancer 10:474–479 21. Morita T, Tei Y, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S (2001) Determinants of the sensation of thirst in terminally ill cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 9:177–186

22. Morita T, Tsunoda J, Inoue S, Chihara S (1999) Perceptions and decision-making on rehydration of terminally ill cancer patients and family members. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 16:509–516 23. Musgrave CF, Bartal N, Opstad J (1995) The sensation of thirst in

24. Musgrave CF, Bartal N, Opstad J (1996) Intravenous hydration for terminal patients: what are the attitudes of Israeli terminal patients, their families, and their health professionals? J Pain Symptom Manage 12:47–51

25. Philip J, Depczynski B (1997) The role of total parenteral nutrition for patients with irreversible bowel obstruction secondary to gynecological malignancy. J Pain Symptom Manage 13:104–111 26. Printz LA (1988) Is withholding hydration a valid comfort

measure in the terminally ill? Geriatrics 43:84–88

27. Smith SA (1997) Controversies in hydrating the terminally ill patient. J Intraven Nurs 20:193–200

28. Solomon MZ, O’Donnell L, Jennings B et al (1993) Decisions near the end of life: professional views on life-sustaining treatments. Am J Public Health 83:14–23

29. Tsai PJ (2004) The ethical dilemma and social work ethical justification for terminal medical communication. Taiwan J Hosp Palliat Care 9:141–152

30. Tsai SL, Hu WY, Chiu TY et al (2004) The knowledge of palliative care amongst senior medical students undertaking the course“family, society and medicine”. Formosan J Med 8:313– 322

31. Weissman DE, Ambuel B, Norton AJ, Wang-Cheng R, Schieder-mayer D (1998) A survey of competencies and concerns in end-of-life care for physician trainees. J Pain Symptom Manage 15:82–90

32. Wurzbach ME (1995) Long-term care nurses’ moral convictions. J Adv Nurs 21:1059–1064