英語教師對課室互動及提問策略的信念與教學實踐之個案研究 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) An English Teacher’s Beliefs and Practices about Classroom Interaction and Questioning: A Case Study. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. A Master Thesis Presented to Department of English,. National Chengchi University. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. by I-Shan Chang July, 2010.

(3) Acknowledgements. The thesis would not have been completed without the support and encouragement of the following people. First, my highest and sincerest appreciation goes to my advisor, Dr. Yu. I am deeply grateful for his suggestions and feedback on the study. Without his insightful guidance, this thesis would have been far more difficult to accomplish.. 立. 政 治 大. My appreciation also goes to my two committee members, Professor. ‧ 國. 學. Chin-Ching Peng and Professor Chia-Yi Lee. I want to thank them for their kindness,. ‧. valuable comments and thorough guidance.. My gratitude is especially given to my college, Helen. Thanks for her assistance. y. Nat. sit. in various ways while I conducted this study. I would also like to thank the. n. al. er. io. participating students. They welcomed me into their classroom and cooperated. i n U. v. throughout the study. Without their participation and cooperation, I would not have. Ch. been able to proceed with my study.. engchi. Finally, I want to deliver my thanks to my beloved husband and my family. With their love and encouragement, I could devote all my efforts to the thesis writing. They accompanied me through my hard days in the completion of the thesis.. iii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………………………………. iii List of Tables…………………………………………….……….……………………………………………………..vi List of Figures…………………………………………….……………………………………………………………vii Chinese Abstract…………………………………….……………………………………..………………………viii English Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….……………………….ix Chapter One: Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Purpose of the Study……………………………………………………………….………………………. 4 Significance of the Study……………………………………………………….…………………………. 4 Chapter Two: Literature Review…………………………………………………………………….. 5 Classroom Interaction……………………………………………………………………………………. 5 The Significance of Classroom Interaction……………………….…………………………. 5 Choice of Language…………………………………………………….……………………………… 6 Activity Type…………………………………………………….………………………………………… 7 Communicative Language Use………………………………………………….……………….. 8 The Purpose of Teachers’ Questioning………………………………………….……………. 9 Teachers’ Questioning Types…………………………………………………………………… 9 Teachers’ Questioning Strategies……………………………………………………………... 10 Teachers’ Beliefs………………………………………………………………………...…………………. 11 The Source of Teachers’ Beliefs………..……………………………………………………… 14 The Relationships between Teachers’ Beliefs and Classroom Practices ……15 Factors that Influence Beliefs and Teaching Practices…………..………………….. 18 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. Teachers’ Beliefs on Classroom Interaction and Questioning …………………….20 Research Questions.……………………………………………………………………………….……21. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Chapter Three: Methodology………………………………………………….………………………. 23 Participants ...…………………………………………………………………………….………………..…23 Instruments…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 25 Semi‐structured Interview ………………………………………………………………….…..25 Stimulated Recall Interview ……………………………..…….…………………………………27 Classroom Observation………………………………….………………………………….…… 28 Field Notes………………………………………………………………………………………………. 28 Procedure……………………………………………………………………………………….……………… 28 Data Analysis……………………………………………………………………………………………….. ..30 Validity and Reliability…………………………………………………………………………….……… 33 Chapter Four: Results…………………………………………………….……………………………….…. 33 Teachers’ Beliefs……………………………………………………..……………….………………………33 The Significance of Classroom Interaction………...………………………………..…….34 iv.

(5) Choice of Language……………………………………………….………………..…………………36 Activity Type……………………………………………………….….………………………………….37 Communicative Language Use……..……………………………………………..…………….39 The Purpose of Teachers’ Questioning………………….……………………………………40 Teachers’ Questioning Type………………………………………………………………………41 Teachers’ Questioning Strategies…………………………..…………………………………..42 Teachers’ Classroom Practices……………………………………..………………………………....46 The Significance of Classroom Interaction……..……….….……………………………..46 Choice of Language………………………………………….…….……………....….…………….48 Activity Type ……………………………………………………….……………….……………………50 Communicative Language Use……………………………….………..……..…………………51 The Purpose of Teachers’ Questioning……………………………………………………….52 Teachers’ Questioning Type…………………..…………………………………………………..55 Teachers’ Questioning Strategies………………..……………………………………………..57 Consistency and Inconsistency between the Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices...60 Consistency……………………………………………………………..……………..…………………60 Inconsistency………………………………….…………………………………………………………62 Chapter Five: Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………….. 66 Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices…………………………………..…………………………………...66 Consistency and Inconsistency…………………………………………………….………..………. 72 Factors Leading to the Inconsistency……………………………….……………….……………. 75 Chapter Six: Conclusions and Implications……………………………………………………………79 Summary of the Study……………………………………………………………………………………. 79 Implications……………………………………………………………………………………….….………. 81 Limitations………………………………………………………………………..……………….……………82 Suggestions for Future Research………………………..…………………………….…………… 83 References.………………………………………………….…………………….……………………………..84 Appendixes Appendix 1: Questionnaire on Participant’s Background (Chinese Version)……... 88 Appendix 2: Questionnaire on Participant’s Background (English Version)………. 89 Appendix 3: Semi‐structured Interviewing Questions (Chinese Version)…………. 90 Appendix 4: Semi‐structured Interviewing Questions (English Version)…………… 91 Appendix 5: Stimulated Recall Interviewing Questions (Chinese Version)…..……. 92 Appendix 6: Stimulated Recall Interviewing Questions (English Version)….………. 93 Appendix 7: Sample of Classroom Observations………………………………………….…. 94 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

(6) LIST of TABLES Table 1: Definitions of Teachers’ Beliefs………………………………………………………………. 13 Table 2: Demographic Data of the Participating Teacher…………………………………………24 Table 3: Examples of Semi‐structured Interviewing Questions…………………………………26 Table 4: Examples of Stimulated Recall Interviewing Questions……………………………….27 Table 5: Summary of the Beliefs…………………………………………………………………………….. 45 Table 6: Summary of the Practices…………………………………………….………………………….. 58 Table 7: Consistency or Inconsistency between the Beliefs and Practices…………….….62 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

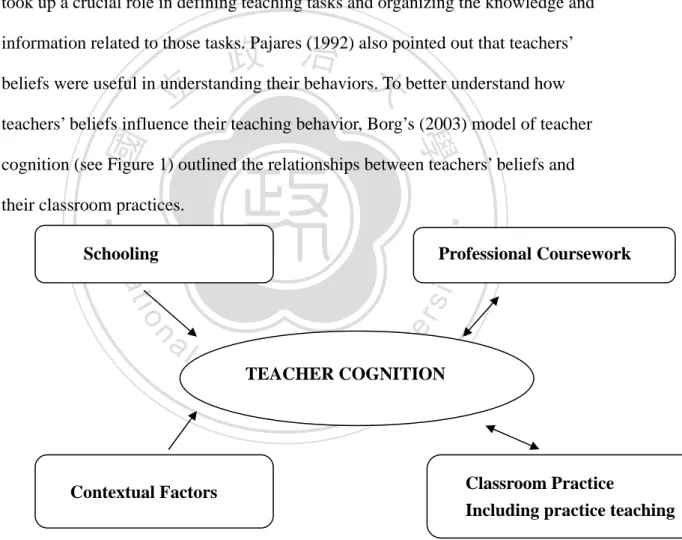

(7) LIST of FIGURES Figure 1: Borg’s (2003) Model of Teacher Cognition………………………………………………15 . 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i n U. v.

(8) 國立政治大學英國語文學系碩士在職專班 碩士論文提要. 論文名稱: 英文教師對課室互動及提問策略的信念與教學實踐之個案研究 指導教授: 余明忠 研究生: 張依珊 論文提要內容 :. 立. 政 治 大. 本研究旨在探討一位國中英語教師對於課室互動及提問策略的信念與教學. ‧ 國. 學. 實務。資料搜集與分析採質性之資料收集及分析法,以期對於該英語教師之信念 及教學能有整體的瞭解。參與本研究教師及學生為台中市一所中型公立國中的一. ‧. 位英文教師及一個七年級班級,期間自九十八年八月至十二月初。資料蒐集方式. y. Nat. sit. 以訪談、課室觀察及回憶式訪談的逐字稿為主。. n. al. er. io. 以課室互動的七個面向來探討及呈現此位國中英語教師對於課室互動及提問. i n U. v. 策略的信念與教學實務。研究結果指出該受訪英語教師的教學信念與實務在課室. Ch. engchi. 互動的重要性、語言的使用、提問的目的、提問的類型與提問策略等五個面向呈 紫現一致性,唯活動類型、溝通式語言的使用面向不一致。研究結果發現該受訪 英語教師教學實務深受其教學信念影響,而造成老師信念及實際上課些微差異的 因素包括教科書、時間緊迫、大班級的呈現方式、學生的語言能力不足及班級裡 頭學生語言能力個別差異大。研究者根據這些發現,提出了對英語教學的看法及 未來研究方向的建議,以期對於課室互動及提問策略有整體的瞭解。. viii.

(9) ABSTRACT The study attempts to better understand what beliefs a junior high school English teacher had with regard to classroom interaction and questioning, and how these beliefs were reflected in her actual practices. To achieve the purpose, qualitative methods were adopted to capture a holistic understanding of the teacher’s beliefs and practices. The participants included one junior high school English teacher and one. 政 治 大. seventh grade class in a medium-sized school in Taichung city. Data were collected. 立. from August of 2008 to December of 2008. Data from semi-structured interviews,. ‧ 國. 學. classroom observations, stimulated recall interview, and field notes were analyzed to see the teacher’s beliefs and teaching practices about classroom interaction and. ‧. questioning.. y. Nat. io. sit. Seven elements derived from classroom interaction and questioning were used to. n. al. er. display the teacher’s beliefs and practices. The results of this study revealed the. i n U. v. consistency of the participating teacher’s beliefs and practices in five areas: the. Ch. engchi. significance of classroom interaction, choice of language, the purpose of questioning, teachers’ questioning types and teachers’ questioning strategies. The inconsistency between the teacher’s beliefs and practices was found on the elements of activity types and communicative language use. The results of the consistency between the teacher’s beliefs and practices showed that the teacher’s beliefs greatly influenced the way how she carried out instructional classroom practices. The results of inconsistency, on the other hand, suggesting a mismatch between the teacher’s beliefs and practices, were associated with the following factors, i.e., textbooks, time constraints, large class, students’ limited and diverse proficiency in English. Based on ix.

(10) the findings, pedagogical implications and suggestions for future research were recommended. It is hoped to provide insights into the dynamics of classroom interaction and questioning.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. x. i n U. v.

(11) CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION Traditional English education in Taiwan used to emphasize reading skills. Most junior high school English teachers used the grammar translation teaching method to meet the expectations of the national curriculum. However, the old curriculum, developed in 1985, was under serious criticism for not providing an adequate level of basic oral and aural communication competences for junior high school students after they had studied English for three years. Therefore, the. 政 治 大 school English education. The revised curriculum was introduced in1994. It places 立 Ministry of Education in Taiwan began working actively to reform junior high. an emphasis on promoting students’ communicative competence. According to. ‧ 國. 學. Richard (2001), communicative competence is “the capacity to use language. ‧. appropriately in communication based on the setting, the roles of the participants,. sit. y. Nat. and the nature of the transaction” (p.36). To develop students’ communicative. io. er. competence in English, classroom interaction is significant in that theories of communicative competence emphasize the importance of interaction as human. al. n. v i n C hcontexts to negotiateUmeaning and then collaborate beings use language in various engchi to accomplish certain purposes (Brown, 2001).. Classroom interaction, as defined by Brown (2001) is “the collaborative exchange of thoughts, feelings, or ideas between two or more people, resulting in a reciprocal effect on each other” (p.165). According to Chaudron (1988), classroom interaction provides the best opportunities for the learners to exercise target language skills, to test out their hypothesis about the target language, and to get useful feedback. Given the importance of classroom interaction to pedagogy, several of the factors that have been considered to influence the quality and quantity of classroom interaction were examined by some researchers (Brock, 1.

(12) 1986; Chaudron, 1988; Long & Sato, 1983; Nunan,1987; Richards & Lockhart, 1996). The major areas that have received much research attention are interactional patterns, choice of language, activity types, questioning behavior, and feedback. Among the factors of classroom interaction, teachers’ questioning behavior is particularly characteristic of classroom interaction in that a review of research on teachers’ questioning has revealed that questioning has been one of the most commonly employed techniques for classroom interaction. As Daly et al. (1994). 政 治 大 up a significant portion of the day. Across all grade levels, approximately 70 立. pointed out, “In classrooms, questioning on the part of teacher and students takes. percent of average school day interaction is occupied with the activity” (p. 27). In. ‧ 國. 學. other words, both teachers and students’ questions constitute most of the. ‧. classroom interaction.. sit. y. Nat. Teachers’ questioning is a way to provide learners with more opportunities. io. er. for interaction. In language classrooms where language learning is a main goal, teachers’ questioning of students not only provides opportunities for students to. al. n. v i n practice the target language,C but also helps make greater h e n g c h i U quantities of target. language input comprehensible (Long & Sato, 1983). Furthermore, Wilen (1986) pointed out questioning has been seen as an influential teaching act in that it is the most basic way teachers use to stimulate participation, thinking and learning in the classroom. Due to the significance of classroom interaction and teachers’ questioning, they are naturally of special interest to teachers and researchers alike. Despite the fact that considerable research has been conducted on teacher’s questioning in language classrooms, only a limited amount of empirical attention has been given to the language classrooms in places like Taiwan, where culture values are 2.

(13) different from those in classrooms in the West, and where the teaching context such as large class size is a practical constraint on what teachers may be able to achieve. Furthermore, research on classroom interaction and teachers’ questioning seemed to be generally done in an “observable” dimension. Studies on classroom interaction were mostly conducted from an observer’s perspective without exploring what went on inside the participant’s minds. Take teachers’ questioning as an example: most of the studies on teachers’ questioning seem to focus on. 政 治 大 response they elicited from students (Brock, 1986; Long & Sato, 1983; 立. teachers’ questioning types, teachers’ questioning strategies, and the kinds of. Nunan,1987). Informative as these findings are, what lacks in such research is. ‧ 國. 學. teachers’ perspective. Relatively little attention has been paid to the “unobservable”. ‧. dimensions of classroom interaction: why and when teachers direct a particular. sit. y. Nat. question to whom. What teachers bring into the classroom in terms of their beliefs,. io. er. thoughts, and perspectives about classroom interaction and questioning is as important as the “observable” dimension, but it is largely unexplored in classroom. al. n. v i n C h has been conducted interaction research. Little research on the relationship engchi U. between teachers’ beliefs and questioning. Classroom interaction research will benefit a great deal from conducting research not only from the researcher’s perspective but also from those of the teacher and the learner. As Clark and Peterson (1986) proposed, the process of teaching involves two major domains, teachers’ thought processes, teachers’ actions and their observable effects. In trying to understand how teachers deal with their teaching, it is necessary for us to examine the beliefs which underlie teachers’ classroom actions. To get the fuller picture of the issues, the study was to explore an English teacher’s beliefs and practices about classroom interaction and questioning. 3.

(14) Purpose of the Study The purpose of the study was to probe an English teacher’s beliefs about classroom interaction and questioning. It aimed to explore what beliefs a junior high school teacher had with regard to classroom interaction and questioning, and how these beliefs were reflected in her actual practices. Consistency and inconsistency between the participating teacher’s beliefs and practices were further examined to provide insights into effective teaching practices.. 政 治 大 By investigating teachers’ questioning in EFL context, this study contributes 立 Significance of the Study. a better understanding of how junior high school teachers interact with students in. ‧ 國. 學. the classroom. Classroom interaction plays an important role in language. ‧. classrooms, and an exploration of this interaction is a good way to define a. sit. y. Nat. teacher’s teaching. In addition, the study contributes to minimizing the gap. io. er. between how classroom interaction is currently understood and what is actually happening in the teachers’ inner world. Finally, the study helps teachers critically. al. n. v i n C h classroom practices. analyze their own thinking about Enhancing teachers’ engchi U. consciousness of their beliefs about classroom practice contributes to improving effectiveness in teaching.. 4.

(15) CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW This chapter was divided into three sections. The first two sections brought together two areas of inquiry: one involved reviews of classroom interaction and the other included research on teachers’ beliefs. The last section illustrated the rationale for the current study. Three research questions were presented to examine a junior high school English teacher’s beliefs and practices about classroom interaction and questioning.. 立. 政 治 大 Classroom Interaction. Everything in the classroom is accomplished through interaction from the. ‧ 國. 學. moment the teacher enters the classroom until the end of a lesson. A great deal of. ‧. time in the classroom is devoted both to interaction between the teacher and the. sit. y. Nat. students and among the students themselves. Thus, classroom interaction involves. io. er. many dimensions, such as teacher talk, student talk, feedback, questioning, just to name a few. Since classroom interaction encompasses vast areas of study, in an. al. n. v i n attempt to focus on only theC issues relevant to the U h e n g c h i data involved in the study, the review has been limited to significance of classroom interaction, choice of. language, activity types, communicative language use, the purpose of teachers’ questioning, teachers’ questioning types and teachers’ questioning strategies.. The Significance of Classroom Interaction Classroom interaction, as defined by Brown (2001) is “the collaborative exchange of thoughts, feelings, or ideas between two or more people, resulting in a reciprocal effect on each other” (p.165). Through classroom interaction, teacher and students can negotiate meanings and collaborate to accomplish certain 5.

(16) purposes. Interaction is viewed as significant because “ 1) only through interaction can the learner decompose the target language structures and derive meaning from classroom events, 2) interaction gives learners the opportunities to incorporate target language structures into their own speech, and 3) the meaningfulness for learners of classroom events of any kind, whether thought of as interactive or not, will depend on the extent to which communication has been jointly constructed between the teacher and learners” (Chaudron,1988, p.10). Given its importance to education, it is not surprising that interaction has been the focus or research. 政 治 大 considered to influence the quality and quantity of classroom interaction were 立. attention for many years. In the following section, several factors that have been. examined (Chaudron, 1988; Richard & Lockhart 1996).. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Choice of Language. sit. y. Nat. Much evidence suggests that choice of language addressed to learners. io. er. influences the quality and quantity of classroom interaction (Chaudron, 1988). In a review of this research, it was found that students’ first language (L1) has played. al. n. v i n C h language (L2) teaching. an unfavorable role in the second In the past, L1 was engchi U. believed being a major factor causing negative transfer in linguistic performance of learners. However, so far, most contemporary studies suggested that concrete reasons to English-only methodology were difficult to find. Almost all the available literature has tended to offer the potential advantages of using L1 in the classroom (Hawks, 2001). For instance, learners can use L1 as a communication strategy to compensate for deficiencies in the target language. From the findings, we may conclude that monolingual approach had no solid theoretical evidence to support. Recognizing that there is a role for L1 in the second and foreign language classroom, we would like to know in what possible occasions and advantages that 6.

(17) it may bring to us. Atkinson (1987) identified the following uses for L1: classroom management, co-operating in groups, using translation to highlight a recently taught language item, language analysis, presenting rules that govern grammar, discussing cross-cultural issues, giving complex instructions and prompts, testing, explaining errors, checking for comprehension, and developing circumlocution strategies. The research reviewed has shown that limited and judicious use of the mother tongue in the English classroom does not reduce students’ exposure to English, but rather can assist in the teaching and learning processes.. Activity Type. 立. 政 治 大. A second issue, activity type, which affects both how teachers conceptualize. ‧ 國. 學. teaching as well as the ways they organize their lessons, is thought to have a. ‧. considerable influence on classroom interaction. Research reviewed has shown. sit. y. Nat. that whole-class instructional methods and group work activities were two kinds. io. er. of activities commonly used in language classes. Research on teaching found that whole-class instructional methods were the most commonly used models in public. al. n. v i n school teaching (Richard & C Lockhart, 1996). In whole-class teaching, the teacher hengchi U leads the whole class through a learning task, conducting a class discussion,. eliciting comments around the class, and so forth. It enables the teacher to teach large numbers of students at the same time. However, such instruction is teacher-dominated, with little opportunity for active student participation. To provide learners with a variety of opportunities for communicative interaction, various alternatives have been proposed. The use of group work activities is one frequently cited strategy for changing the interactional dynamics of language classrooms. Richards and Lockhart (1996) pointed out a number of advantages of group work: 7.

(18) 1. It reduces the dominance of the teacher over the class. 2. It increases the amount of student participation in the class. 3. It increases the opportunities for individual students to practice and use new features of the target language. 4. It promotes collaboration among learners. 5. It enables the teacher to work more as a facilitator and consultant. 6. It can give learners a more active role in learning (p.153). Communicative Language Use A third issue of classroom interaction is related to communicative language use. According to Brown (2001), in the era of communicative language teaching,. 政 治 大 about. However, there is 立growing evidence that in communicative classes,. interaction is, in fact, the heart of communication; it is what communication is all. ‧ 國. 學. interaction may not be communicative at all (Nunan,1987). Nunan (1987) pointed out there have been comparatively few studies of actual communicative language. ‧. practices despite the fact that a great deal has been written on the theory and. sit. y. Nat. practice of communicative language teaching. Most classrooms focus on. n. al. er. io. non-communicative language practices in terms of grammatical focus, error. i n U. v. correction, the extensive use of drill and controlled practice, and interactions are. Ch. engchi. pseudo-communicative rather than genuinely communicative. However, some researchers (Brown 2001; Nunan,1987; White & Lightbown,1984) pointed out this kind of language practices provided learners with the necessary prerequisite skills for more communicative language work. While one cannot deny such things as drill and controlled practice have a valid place in the language class, students cannot be deprived of many useful opportunities for using and learning the new language. Learners also need the opportunity to engage in genuine communicative interaction. When learners focus on meaningful tasks or exchanges of information, they can receive 1) comprehensible input from his or her conversational partner, 2) 8.

(19) a chance to ask for clarification as well as feedback on his or her output, 3) adjustment of the input to match the level of the learner’s comprehension, and 4) the opportunity to develop new structures and conversational patterns through this process of interaction (Richards & Lockhart,1996).. The Purpose of Teachers’ Questioning The most important key to creating an interactive language classroom is the initiation of interaction by the teacher. One of the best ways is through teachers’. 政 治 大 was taken up with question-and-answer exchanges. The following reasons 立. questioning. According to Gall (1984), in some classrooms, over half of class time. indicated that why questions were so commonly used in teaching (Richards &. ‧ 國. 學. Lockhart,1996, p.185).. ‧. They stimulate and maintain students’ interest. They encourage students to think and focus on the content of the lesson. They enable a teacher to clarify what a student has said. They enable a teacher to elicit particular structures or vocabulary items. They enable teachers to check students’ understanding. They encourage student participation in a lesson.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Teachers’ Questioning Types Given the importance of teacher questions to pedagogy, numerous studies have been conducted on the use of teacher questions in the content classrooms as well as language classrooms to examine the contribution of teachers’ questions to classroom learning. The classification of teacher questions was called for before an examination of related studies on teacher questions in classrooms. Two questioning types that have received much research attention were Long and Sato’s (1983) classification of display and referential questions: display question, 9.

(20) questions for which the answer is already known to the teacher, and referential questions, questions for which the response is not known to the teacher. Classroom research has also shown that teachers tend to ask more display questions than referential questions. However, display questions serve only to facilitate the recall of information rather than to generate student ideas and classroom communication. Furthermore, they may provide limited opportunities for students to produce and practice the target language. Referential questions, on the other hand, provide learners with considerable opportunities to engage in. 政 治 大 Brock (1986) found that teachers who incorporated more referential questions into 立. meaningful communicative language use to effectively acquire a foreign language.. their classes stimulated student responses that were longer and more. ‧ 國. 學. grammatically complex. However, according to Nunan (1987, p.137), display. ‧. questions can serve as “the necessary prerequisite skills for more communicative. sit. y. Nat. work.” In other words, both of the questions have their place in the interactive. io. n. al. er. classroom and teacher should use them adequately to achieve certain purposes.. Ch. Teachers’ Questioning Strategies. engchi. i n U. v. Research findings have also shown that asking a lot of questions in the classroom will not by any means guarantee stimulation of interaction. Students do not always respond immediately after teachers’ questions. If the reply called for by the teacher does not appear, the teacher may employ questioning strategies. For example, repetition and rephrasing were common questioning strategies that teachers used to make their questions understandable to the learners. It was found that teachers would persist in asking questions by repeating or rephrasing them (White & Lighbown, 1984). In Wu’s (1993) study, a number of questioning strategies were also found: 1) rephrasing, expressing a question in another way. 2) 10.

(21) simplification, simplifying the original question so that students can cope with it. 3) repetition, repeating a question in the hope that a verbal response will be elicited. 4) decomposition, dividing an initial question so that an answer may be obtained. 5) probing, asking one or more other questions following the main question so that the teacher can solicit more responses from a student. Previous studies on classroom interaction and teachers’ questioning for second language classrooms over the past few years have offered some implications for teaching practice: 1) Classroom interaction provided the best. 政 治 大 hypothesis about the target language, and to get useful feedback. 2) Limited and 立 opportunities for the learners to exercise target language skills, to test out their. judicious use of the mother tongue in the English classroom did not reduce. ‧ 國. 學. students’ exposure to English, but rather could assist in the teaching and learning. ‧. processes. 3) The use of group work activities was one strategy for changing the. sit. y. Nat. interactional dynamics of language classrooms. 4) Learners needed the. io. er. opportunity to engage in genuine communicative interaction. 5) Questioning was one of the most commonly employed techniques for classroom interaction. 6). al. n. v i n C hmore classroom interaction, Referential questions promoted but most teachers’ engchi U. questions were restricted to display questions. 7) Teachers’ questioning strategies improved the quality and quantity of interaction.. Teachers’ Beliefs The focus of this section moved from classroom interaction to a review of teachers’ beliefs. The first part discussed the nature of teachers’ beliefs from two perspectives, specifically, the definition of teachers’ beliefs and the characteristics of teachers’ beliefs. The second part described the sources of teachers’ beliefs. The third part discussed the relationships between teachers’ beliefs and classroom 11.

(22) practices. After an overview of the effects of teachers’ beliefs on classroom practices, the researcher went on to discuss empirical evidence of consistency and inconsistency of teachers’ beliefs and practices. Factors that influence beliefs and teaching practices were discussed in the next section. Finally, studies on teachers’ beliefs and classroom interaction and questioning were further illustrated to clarify the great complexity of beliefs and practices.. The Nature of Teachers’ Beliefs. 政 治 大 “beliefs” in different ways. Clark (1988) referred teachers’ beliefs as “implicit 立 The definitions of beliefs are abundant. Researchers have used the term. theories”. Teachers’ beliefs were defined as the combination of personal. ‧ 國. 學. experiences, beliefs, values, biases and even prejudices. Kagan (1992) stated there. ‧. was no shared understanding of the term “teachers’ beliefs”. It may refer. sit. y. Nat. perceptions, assumptions, implicit and explicit theories, judgments, opinions and. io. er. more (Calderhead, 1996; Kagan, 1992; Munby, 1983; Pajares, 1992). Richardson (1996) defined beliefs as the conceptions held by a person. They were. al. n. v i n C h premises, orUpropositions about the world “psychologically held understandings, engchi that are felt to be true” (p.103). Pajares (1992) integrated diverse definitions of different researchers and described beliefs as “teachers’ attitudes about education-about schooling, teaching, learning, and students” (p.316). According to Pajares, when speaking of teachers’ beliefs, researchers referred them to teachers’ educational beliefs, but seldom to the teachers’ broader or general belief system. In this research, beliefs were defined, following Pajares’ (1992) definition, as teachers’ attitudes about education-about schooling, teaching, learning, and students. To enhance more understanding of teacher’s beliefs, the researcher summarized the definitions of teachers’ beliefs in the following table. 12.

(23) Table 1: Definitions of Teachers’ Beliefs. Researcher. Definition of Teachers’ Beliefs. Clark (1988). The combination of personal experiences, beliefs, values, biases and prejudices. Individual ways that teachers understand. Kagan (1990). classroom, students, the nature of learning, teacher’s role in a classroom, and the goals of education. “Teachers’ attitudes about education-about. Pajares (1992). schooling, teaching, learning, and students”. Richardson(1996). 立. (p.316). 政 治 “Psychologically 大 held understandings,. premises, or propositions about the world that. ‧ 國. 學. are felt to be true” (p.103).. ‧. As for the characteristics of teachers’ beliefs, Fang (1996) described beliefs. sit. y. Nat. as mental constructs that: 1) influenced how information was perceived, 2) guided. io. er. teachers’ behavior, 3) were constrained by institutional and classroom realities, 4). al. were influenced by teachers’ professional subcultures, and 5) were shaped by both. n. v i n C h Moreover, U personal and professional experiences. e n g c h i Nespor (1987) identified four more characteristics of beliefs that helped distinguish them from knowledge: existential presumption, alternativity, affective and evaluative loading, and episodic structure. Existential presumption referred to the property that “belief. systems frequently contained propositions or assumptions about the existence or nonexistence of entities” (Nespor, 1987, p.318). For example, teachers might assume the existence of maturity facilitates teamwork. As for alternativitiy, it referred that beliefs sometimes involved a state or situation different from reality and from what one had experienced or encountered. Affected and evaluative loading stressed the elements of feelings, emotions, moods, and evaluations in 13.

(24) beliefs. Finally, episodic structure illustrated the origins of beliefs. They oriented from episodes, namely, personal life experiences, no matter pleasant or not. To summarize, the research reviewed has revealed that beliefs were unconscious or conscious propositions formed based on one’s learning and teaching experiences. Once beliefs were formed, they start serving as the filtering device that influenced how new information was interpreted.. The Source of Teachers’ beliefs. 政 治 大 & Lockhart 1996). First, teachers’ experiences as language learners exert an 立. Teachers’ beliefs are derived from a number of different sources (Richards. influence on teachers. Teachers’ beliefs about teaching are often a reflection of. ‧ 國. 學. how they themselves were taught. In other words, they learn a lot about teaching. ‧. through their vast experience as learners. Second, teachers’ experience is another. sit. y. Nat. primary source that affects their beliefs. For example, some teachers may learn. io. er. from their teaching experiences that some teaching strategies work well for their students and some do not. Therefore, their teaching experiences can inform them. al. n. v i n C h the established practice what works best for them. Third, within a school, an engchi U. institution, or a school district may also shape teachers’ beliefs about language teaching. Certain teaching styles and practices such as group activities may be preferred and encouraged within a school. Fourth, personality factors may influence teachers’ beliefs. For example, some teachers may prefer a particular teaching style because it matches their personalities. Fifth, educationally based, research-based principles or principles derived from an approach or method may also influence teachers’ beliefs. Teachers may believe in the effectiveness of a particular teaching approach such as communicative language teaching, and try to implement it in their classrooms. 14.

(25) The Relationships between Teachers’ Beliefs and Classroom Practices Numerous researchers suggested teachers’ beliefs had a great influence on the way teachers planned their lessons, on the kind of decisions they made, and on their general classroom practices (Clark & Peterson, 1986; Nespor, 1987; Pajares, 1992). For instance, Clark & Peterson (1986) supported the notion that teachers’ thought processes and teaches’ actions were interrelated in and essential to the process of teaching. Another researcher, Nespor (1987) stated that teachers’ beliefs took up a crucial role in defining teaching tasks and organizing the knowledge and. 政 治 大 beliefs were useful in understanding their behaviors. To better understand how 立. information related to those tasks. Pajares (1992) also pointed out that teachers’. teachers’ beliefs influence their teaching behavior, Borg’s (2003) model of teacher. ‧ 國. 學. cognition (see Figure 1) outlined the relationships between teachers’ beliefs and. ‧. their classroom practices.. Professional Coursework. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Schooling. v i n C h TEACHER COGNITION engchi U Classroom Practice Including practice teaching. Contextual Factors. Figure 1 Teacher cognition, schooling, professional education, and classroom practice (Borg, 2003, p.82).. The model suggested that teachers’ extensive schooling experience directly influenced teachers’ beliefs. This experience also shaped teachers’ beliefs during 15.

(26) their initial professional training, which exerted an influence on teachers throughout their career. Moreover, contextual factors played a pivotal role on teachers’ beliefs through classroom practices. Finally, there was a mutual influence between classroom practices and teacher’s beliefs. What teachers believed to be true was reflected in their classroom practices, which in turn shaped their beliefs. In brief, teacher beliefs and practices were closely interrelated, with contextual factors playing an important role in determining the extent to which teachers were able to implement instruction congruent with their beliefs.. 政 治 大 classroom practices is becoming widely accepted in education, various researchers 立 As the importance of the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and their. have conducted studies to examine how teachers’ beliefs affect their practice. ‧ 國. 學. (Calderhead, 1996; Fang, 1996; Pajares, 1992). However, research studies on the. ‧. relationship between teachers’ beliefs and teaching practices vary: some studies. sit. y. Nat. revealed the consistencies between teachers’ beliefs and their classroom practices. io. er. while other studies found large discrepancies between teacher’ espoused beliefs and their observed classroom practices. This leads to the need to review empirical. al. n. v i n evidence on the consistencyC or inconsistency between h e n g c h i U teachers’ beliefs and practices.. According to Fang (1996), a substantial number of studies on reading supported the idea that teachers did possess theoretical beliefs towards reading and such beliefs tended to shape the nature of teachers’ instructional practices. A strong relationship between beliefs and practices was also verified in Johnson’s (1992) study. Johnson explored the relationship between ESL teachers’ beliefs and practices. Findings of his study suggested that the teachers who possessed clearly defined theoretical beliefs provided literacy instruction which was congruent with their theoretical orientation. The study supported the consistency theory that 16.

(27) teachers’ teaching practices were in concordance with their beliefs. However, a number of studies have highlighted that there were inconsistencies between teachers’ beliefs and their observed practices. For instance, Graden (1996) compared six secondary foreign language teachers’ beliefs about effective second language reading instruction with their instructional classroom practices. Participants were six French and Spanish teachers teaching at three public schools. Data were collected through entry and exit teacher interviews, audio-taped classroom observations, and observational field notes. Findings from. 政 治 大 consistent with their beliefs, but their multiple belief systems were in conflict in 立. the study supported previous studies that the teachers’ practices were generally. the classroom. Thus, the teachers compromised certain beliefs in their classrooms.. ‧ 國. 學. It was found that the teachers’ choices to accommodate their students took. ‧. precedence over their beliefs about appropriate reading instruction.. sit. y. Nat. Another study pointing out the incongruity between teachers’ beliefs and. io. er. practices was conducted by Rust (1994). In Rust’s study, the relationship between teachers’ espoused belief and beliefs in action were examined. The participants. al. n. v i n were two beginning teachersCwho entered their first h e n g c h i Uyear of teaching. Data were. collected through a beliefs questionnaire, dialogue journals, and interviews. The study revealed the participating teachers’ espoused beliefs were not always in consistent with their classroom practices. Both teachers ended up behaving in ways that were inconsistent with their images of the good teacher. Because of the inconsistency, their previously formed beliefs changed along with their teaching experiences and teaching contexts. The following section continued and discussed the factors that may contribute to the inconsistency between teachers’ beliefs and their actual classroom practices.. 17.

(28) Factors that Influence Beliefs and Teaching Practices While many research findings suggested consistency between teachers’ beliefs and their instructional practices, some indicated that at times inconsistency did occur (Calderhead & Shorrock, 1997; Clark & Peterson 1986; Duffy & Anderson, 1984). Research has shown that teachers’ classroom behaviors may be influenced not only teachers’ beliefs but also by other variables (Calderhead & Shorrock, 1997; Graden, 1996). In other words, when it comes to teaching practices, it is inevitable to touch upon the constraints that impose on the teaching. 政 治 大 difficulties for teachers to implement what they believe, and this led to the 立. process, as Fang (1996) claimed that complexities of classroom life could create. conclusion that teachers’ beliefs and practices were influenced from contextual. ‧ 國. 學. factors.. ‧. Researchers have proposed a host of factors related to the inconsistency. sit. y. Nat. between teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices (Calderhead & Shorrock, 1997;. io. er. Clark & Peterson 1986; Duffy & Anderson, 1984). For instance, Duffy and Anderson’s (1984) study indicated that teachers’ classroom practices were often. al. n. v i n C hcurriculum materials associated with decisions about and resources, instructional engchi U time, and student abilities. Graden (1996) found that even though teachers were aware of their beliefs about reading instruction, they implemented practices inconsistent with their beliefs under the influence of student factors. Clark and Peterson (1986) also asserted that teachers’ actions were often constrained by the physical setting or by external influences, such as the school, the principal, the community, or the curriculum. Calderhead & Shorrock (1997) further pointed out three groups of factors that influenced teachers’ practices, namely, socio-cultural factors, personal factors, and technical factors. First, socio-cultural factors were concerned with practices 18.

(29) within the school, as well as the expectations from children, parents, colleagues. In most schools, there were clear expectations for teachers to follow; hence, teachers felt under pressure to conform to these establishments. Second, teachers’ personal factors referred to teachers’ self-image of being a teacher, their past experiences of schooling, and their beliefs about good teaching. The way teachers thought about themselves would act as a powerful influence on teaching. Finally, technical factors including textbook ideas and strategies, physical and resource constraints that existed within the school also had a great influence on the. 政 治 大 In Taiwan, Hsu (2007) conducted a case study to investigate factors leading 立. development of teachers’ teaching practices.. to discrepancies between teachers’ beliefs and their teaching practices. He delved. ‧ 國. 學. into two junior high school English teachers’ beliefs and teaching practicum. ‧. toward grammar teaching. Data were collected through open-ended questionnaires,. sit. y. Nat. verbatim transcriptions of primary interviews, non-participant observations, and. io. er. stimulated recall interviews. Findings of the study revealed that three major factors led to the inconsistency between the participating teachers’ beliefs and. al. n. v i n C h teachers’ prior teaching their teaching practices including experience, time engchi U constraints, and the textbook.. Literature reviewed indicated that surrounded by the constraints of teaching contexts or other factors, teachers’ classroom practices did not always correspond to their beliefs. Once the inconsistency occurs between teachers’ beliefs and classroom practices, learners will receive confusing messages, and this therefore undermines learning outcomes and teaching effectiveness.. Teachers’ Beliefs on Classroom Interaction and Questioning Although a growing body of research continues to probe into the 19.

(30) relationship between language teachers’ beliefs and practices, few investigations have extended this research to classroom interaction, in particular to teachers’ questioning practices. Only a few studies explored the relationships between teachers’ beliefs and practices about classroom interaction. One study was conducted by Sahin & Stables (2002). They examined the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and their practices about questioning at Key Stage 2 (age 7-11). Data were collected from interview and classroom observations. Data analysis was based on a Straussian approach to grounded theory. Findings suggested a. 政 治 大 teachers used a variety of skills during their teaching that they may not always be 立 mismatch between teachers’ beliefs and teaching practices. It was found that. aware of.. ‧ 國. 學. Another study was conducted by Hussin (2006). To explore teachers’. ‧. rationale for adopting certain techniques of questioning, Hussin conducted a study. sit. y. Nat. on questioning practices in Malaysian secondary school. This study employed a. io. er. qualitative research method including interviews and classroom observations. It was found that the majority of questions in the classrooms were low-level and. al. n. v i n factual, and not designed to C encourage critical thinking h e n g c h i U on the part of learners.. What was set by the national curriculum was different from how teachers actually teach in terms of posing questions. Teachers’ beliefs about their students’ academic needs and others made them tailor their questions to align with the examinations. In Taiwan, Kuo’s (2008) study was the first one that explored the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and practices about classroom interaction. He conducted a case study to investigate the relationships between an English teacher’s beliefs and her teaching practices. Data from interviews and observational field notes were analyzed to see convergence and divergence of the 20.

(31) teacher’s beliefs and teachings. The results of this study indicated that a relaxing atmosphere and harmony were two key elements that the participating teacher emphasized in the classroom interaction with students. The findings were informative but classroom interaction was only discussed in a small section. A more thorough examination on the topic of teachers’ beliefs and practices about classroom interaction could be done. Given all these findings, the importance of classroom interaction and questioning practices cannot be denied. However, studies reviewed showed that. 政 治 大 classroom context in Taiwan. Furthermore, research on classroom interaction and 立 classroom interaction and questioning are under-researched areas in EFL. teachers’ questioning seemed to be generally done in an “observable” dimension.. ‧ 國. 學. Studies on classroom interaction were most conducted from an observer’s. ‧. perspective without exploring what went on inside the participant’s minds. What. sit. y. Nat. teachers bring into the classroom in terms of their beliefs, thoughts, and. io. er. perspectives about classroom interaction and questioning is as important as the “observable” dimension, but it is largely unexplored in classroom interaction. al. n. v i n C h of the issues, theUstudy was to explore a junior research. To get the fuller picture engchi high school English teacher’s beliefs and practices about classroom interaction and questioning.. Research Questions To examine the issues stated above, the research questions were focused on the following three main areas:. 1. What are the English teacher’s beliefs about classroom interaction and questioning? 21.

(32) 2. How does the English teacher actually practice during lessons? 3. What are the consistency and inconsistency between the English teacher’s beliefs and practices?. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 22. i n U. v.

(33) CHAPTER THREE METHODOLOGY The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between a junior high school English teacher’s beliefs and her teaching practices, particularly in classroom interaction and questioning. To achieve the purpose, qualitative methods were adopted including semi-structured interviews (see Appendixes 3 & 4), classroom observations (see Appendix 7), stimulated recall interviews (see Appendixes 5 & 6), and field notes. This section provided an overview of the. 政 治 大 instruments, data collection procedures, and data analysis. Issues dealing with 立. methodology used in the study, which included the participants, data collection. validity and reliability were further illustrated in the final section of the chapter.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 Participant. sit. y. Nat. The study was designed to explore a junior high school English teacher’s. io. er. beliefs and teaching practices toward classroom interaction and questioning practices. In order to achieve this goal, one female junior high school English. al. n. v i n C h For ethicalUreasons, the name of the teacher was selected as the participant. engchi. teacher was kept pseudonymous in the present study and she was referred to as Helen. The participant was selected based on two criteria. The first reason was Helen’s high frequency of questioning practices in English teaching. To ensure that the selected teacher was suitable for the study, the researcher observed her teaching at least three times. Repeated classroom observations would be enough to yield insight into the general patterns of the participating teacher’s teaching practices. It was observed that Helen asked questions frequently in her instruction. In addition, her classes were quite interactive. It was mainly because of these 23.

(34) personal teaching characteristics that she was selected for this research project. The second criterion was based on the participating teacher’s consent. It is really a tough job to find qualified participants who are willing to be observed and recorded for a period of time. Teachers are often reluctant to take part in observation since observation is associated with evaluation. After gaining a full understanding of the purpose of this study, Helen viewed the observations as a positive experience which may help trigger some insight of her teaching. She thus agreed to be the participant. The table below demonstrates the demographic data of the participating teacher.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. io. 5. v. 7th & 8th graders. n. al. sit. English Department, University. Years of teaching experience Coverage of students. y. 30. er. Diploma. Female. Nat. Age. Helen. ‧. Gender. 學. Table 2 Demographic Data of the Participating Teacher. Ch. Observed class: The ratio of male to female students. i n U. 15/15. i e n g c h Mandarin Chinese; Taiwanese. Students’ mother tongues in observed class. Helen’s school is located in Taichung city. It is a medium-sized junior high school with 54 classes in total. This public school is well-known for its liberal and lively atmosphere. The students are evaluated not only by their academic achievements, but also by their extracurricular performances. During the period the present study was conducted, Helen had four English classes. Her students were in the seventh and eighth grade. The participating students were an intact class of seventh grade students. They were selected from 24.

(35) one of Helen’s classes, based on her perception of the students’ active classroom participation and interaction because the primary focus of the study was on classroom interaction and teachers’ questioning practices.. Instruments According to Calderhead (1996), there are various types of methods for tackling teachers’ beliefs. One of them is case study, which involves extensive observation and interviews on the same or several teachers over a long period of. 政 治 大 insights into teachers’ implicit theories. The present study aimed to examine a 立 time. The detailed accounts of teachers’ actions and talk over time can yield. junior high school English teacher’s beliefs and practices towards classroom. ‧ 國. 學. interaction and questioning. For better understanding of her views, a case study. ‧. approach was adopted. Moreover, research on teachers’ beliefs revealed that the. sit. y. Nat. most frequently adopted instruments were questionnaires, interviews, and. io. er. classroom observations (Calderhead, 1996; Clark & Peterson, 1986). Therefore, in this study, interviews and classroom observations served as the major sources of. al. n. v i n C understanding the qualitative data needed for under study. U h e n g c hthei phenomenon Questionnaires were not adopted in that they have been criticized as. pre-determining options and thus limiting a wide range of possibilities (Calderhead, 1996). To conclude, the researcher employed a variety of instruments including semi-structured interviews, classroom observations, stimulated recall interviews, and field notes to confirm the emerging findings.. Semi-structured Interview Two different forms of interview were adopted in the present study, specifically, semi-structured interviews and stimulated recall interviews. The first 25.

數據

Outline

相關文件

配合小學數學科課程的推行,與參與的學校 協作研究及發展 推動 STEM

(計畫名稱/Title of the Project) 提升學習動機與解決實務問題能力於實用課程之研究- 以交通工程課程為例/A Study on the Promotion of Learning Motivation and Practical

The study applies Discriminate Analysis to discuss the aspects of Junior high school students living Adjustment Scale and then develops a scale to be the standard of Junior

The purposes of this research was to investigate relations among learning motivation, learning strategies and satisfaction for junior high school students, as well as to identify

This research tries to understand the current situation of supplementary education of junior high school in Taichung City and investigate the learning factors and

This purpose of study was to realize, as well as the factors of influence of information technology integrated in teaching by junior high school special education teachers in

This study was conducted to understand the latest situation between perception of principal‘s leading role and school effectiveness in junior high schools, and

The aim of this research is to study changes resulting from parents attending a study group designed by class teacher that include reading a chosen book and engaging in