國立臺灣大學文學院語言學研究所 碩士論文

Graduate Institute of Linguistics College of Liberal Arts

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

點亮咖啡香:從認知語言學理解風味的跨感官表達

Brighten Up Your Coffee! Crossmodal Expressions of Flavor in Taiwan Mandarin within a Cognitive Linguistic Framework

張亦萱

Umy Yi-hsuan Chang 指導教授:江文瑜 博士 Advisor: Wen-yu, Chiang, Ph.D.

中華民國 107 年 7 月

July, 2018

國立臺灣大學碩士學位論文

口試委員會審定書

點亮咖啡香:從認知語言學理解風味的跨戚官表達 Brighten Your Coffee Up! Crossmodal Expressions of

Flavor in Taiwan Mandarin within Cognitive Linguistic Framework

本論文亻系張亦萱君 (R03142002) 在國立臺灣大學語言學趼究所 完成之碩士學位論文,於民國 106 年 l 月 16 日承下列考試委員審查通 過及口試及格,特此證明

口試委員: 尸i}:___� � (簽名)

(挂導教授)

-- 二

謝辭

隨著論文終能付梓成冊,語言所的學習生涯也將告一段落。一路走來,每每在我遇到 寫作亦或學習瓶頸時,總有師長、家人、親友開導與關懷,最後終得豐美碩果。如果沒有 各方對我的照顧,絕不可能獲得今日成就。

首先感謝我的論文指導教授江文瑜博士,從碩二開始的引導研究就一步一步細心的指 導論文寫作,更在這兩年的論文寫作過程中,對於學生各式發表作品逐字逐句地檢閱。總 是犧牲個人時間,將學生作品雕琢至精華,僅此致上萬分謝忱。

感謝口試委員魏美瑤教授於審查時,惠賜寶貴的建議,澄清許多研究盲點,讓我受益 匪淺;感謝口試委員呂佳蓉教授,於百忙中仍願意撥空謹慎審查,口試後仍不時細心審閱 與指教,讓本論文更臻於完善。

感謝在學術之路的師長們,蘇以文教授、宋麗梅教授、馮怡蓁教授、謝舒凱教授、李 佳霖教授,於我碩士生活以來,給予許多語言學知識的啟蒙與紮根,使得研究方法紮根穩 固。所上師長們的教誨與協助,不僅使我收穫良多,對於論文的完成更是莫大的幫助。

感謝所上學長姐們,在我忙碌的碩論撰寫時光,增添了豐富的色彩:塔口學姊始終如

一的爽朗笑聲與高效率協助,總是帶領我走出學術寫作的苦悶、Chester 學長專業與豐富的

學術建議,讓口試發表當天更臻完美、Thomas 口試時適時提點,讓後續的修改更加完美、

逸如姐建議的論文參考資料,拓展了我在此領域的背景知識。感謝同研究室、曾一起同甘 共苦的文怡,還有一同奮戰論文的所上同學們。因為與你們分享研究與生活,彼此鼓勵與 包容,使我在論文寫作中,少了憂愁與苦悶,多了熱情與動力。感謝學弟妹們的加油與打 氣,有你們真好。

感謝玉米,打從報考語言所到口試前一晚,不管是在圖書館力拚論文,還是在簡報室 排練,總是陪伴著我,堅信我絕能達成。感謝社團老師與合唱夥伴,不論苦樂相持相隨。

也感謝室友紅茶與Taco,儘管碩士論文的領域截然不同,精神上與實質上,仍是彼此重要

的支持。

最後特別感謝爸媽,感念您們對我從小到大的栽培,支持我大學後選擇邁向語言學的 道路,精進學業並獲得另一項專業。

謹將此篇論文獻給自己與所有關愛我的家人、老師與朋友們。

張亦萱 謹致 中華民國一〇七年七月 台大文學院

摘要

本篇研究從認知語言學的角度出發,探討中文母語人士對風味的感受中,如何 以跨感官的方式呈現。風味是直接的嗅覺與味覺體驗,然也普遍認為過於主觀、空 虛、抽象,難以具體形塑與表達的感官經驗。而在經由文獻回顧後,可察覺中文母 語人士在表達風味體驗時,常藉由非味覺與嗅覺的修辭,作為風味的表徵。本論文 以綜觀的角度探討 風味描述中以跨感官用詞描繪的隱喻結構與種類,也從語用的視 角檢視跨感官隱喻修辭的目的,進而觀察評鑑者(即說話者)與傾聽者共同建構與 共鳴的現象。

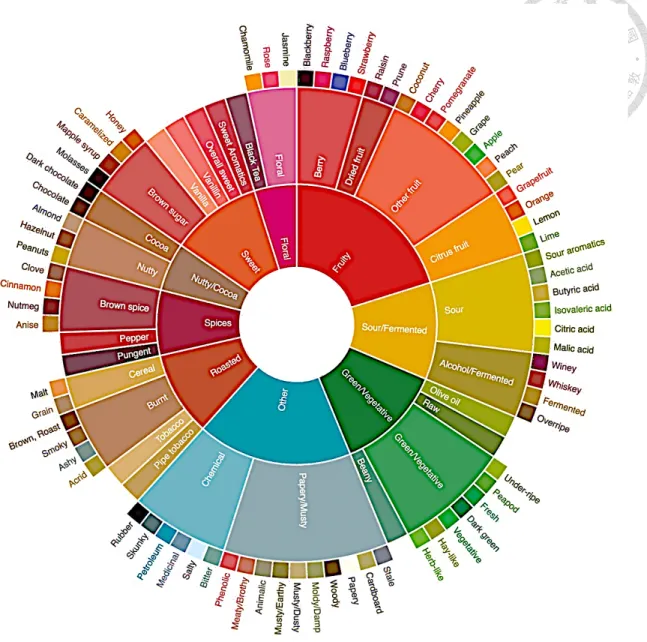

本研究以質化的方式分析及檢視語料。對於飲食的感官評析,不少飲食(如紅酒、

橄欖油、巧克力、咖啡等等)在製造過程中,必須經由繁瑣的官能鑑定流程,依據統

一的風味輪作為量表,始能具體評斷食品的風味優劣。其中,尤以咖啡的風味表達尚未

有深入的探討與研究。而咖啡統一的制式化咖啡風味輪(由Specialty Coffee Association of America 制定),並無法全然與中文對應,並讓中文使用者理解。因此,為了補足現 有研究的不足,本論文從錄像搜集共十小時咖啡官能鑑定過程,並人工轉寫錄影中的 風味描述與評析逾兩萬字,作為研究之語料基礎。並提出三個跨感官表達結構 (1) 跨 感官隱喻(即共感隱喻Synesthetic Metaphor)(2) 跨感官轉喻(即共感轉喻 Synesthetic

Metonymy)(3) 跨感官明喻(即共感明喻 Synesthetic Simile),以進一步解析風味的表

達,與不同知覺間跨感官的聯繫,或與情感、記憶、文化間的微妙關係。研究結果發 現,評鑑者運用跨感官隱喻將視覺、聽覺與觸覺中的描繪詞轉而形容風味,跨感官轉 喻則為概念式隱喻多是上、少是下(More is up, less is down)環環相扣,而跨感官明喻 則藉由意象基模(Image schema)與原形理論(Prototype theory)以期在風味描述中達到說 服、感性鋪陳、或感同身受等溝通目的。

再者,本文也提出不同於以往研究中跨感官表現的方向性,並提出可能的修改方 向。最後,本論文旨在彰顯跨感官結構在知覺感受表達中所扮演的重要角色,並提倡 在語言學中建立知覺與言談(Perception and Discourse)為一研究領域。藉由提出風味表 達中的共感隱喻、共感轉喻、及共感明喻的結構,本論文探究嗅覺、味覺與其他知覺 如何互動、整合。透過多模態隱喻詮釋,解析語言之於知覺與文化的關聯性,希望能 跳脫單純的語言結構與詞彙的脈絡,從認知語言學的角度,進一步釐清人類認知與感 受的歷程。

關鍵字: 跨感官表達、風味、共感隱喻、共感轉喻、共感明喻、多模態隱喻、

言談分析、知覺感受與語言、咖啡杯測評鑑

ABSTRACT

This study aims to explore how flavor is conceptualized crossmodally in perceptions from the perspective of cognitive linguistics by analyzing data collected from coffee cupping events in Taiwan. Although the instinctive senses of smell, taste, and flavor are shared by all, the instrumental convergence of language seems impracticable for conveying such subjective, elusive, and abstract sensation. However, it is through language that our experience of flavor can be reconstructed, evaluated, and expressed (Dyer 2011). The gap between the inexpressible nature of the so-called primitive sensations (i.e., of smell and taste) and language is bridged through figurative expressions like metaphors and similes.

Notwithstanding, rarely can we identify the Chinese counterparts of English flavor descriptors, nor is the language of savoring experiences in Chinese well studied.

Although coffee cupping involves abundant crossmodal expressions, previous studies have scarcely addressed coffee cupping; instead, wine tasting is a more common topic. To bridge this research gap, the current study conducts a corpus-based investigation on cupping data involving 27,043 words from a 10-hour recording. Based on previous flavor researches (e.g., Paradis, 2013), this study places emphasis on the following three aspects to investigate the highly context-dependent synesthetic expressions (i.e., expressions of crossmodal mappings) found during coffee cupping: crossmodal metaphor (i.e., synesthetic metaphor), crossmodal metonymy (i.e., synesthetic metonymy), and crossmodal simile (i.e., synesthetic simile). However, different from the hypotheses of previous researches, we propose a novel directionality of perceptual transfers in crossmodal interactions. In fact, there is no particular rule that crossmodality in linguistic expressions must obey or violate a certain directionality in terms of the perceptual and conceptual mechanisms within sensory expressions.

According to our findings, the crossmodal metaphors featuring interactions across touch, sight, taste, and smell are regarded as synesthetic metaphors; the crossmodal metonymy is in fact transferred from the general conceptual metaphor of MORE IS UP, LESS IS DOWN,and is referred as synesthetic metonymy; the crossmodal associating (i.e. synesthetic simile), analyzed through Image schema and Prototype theory, constructs two pathways of both human cognition and emotion in order to perceptually comprehend and emotionally participate flavor experiences. In sum, three complicated crossmodal formations (i.e.,

synesthetic metaphor, metonymy, and simile) have been established simply due to the human cognitive ability to demonstrate linguistic representation as a unity of senses (see Marks, 1978).

Further, by thoroughly analyzing synesthetic forms and functions, the present study aims to deepen an understanding of the emerging role of crossmodality in flavor expressions through the elaboration of the linguistic mechanisms of flavor expressions. By analyzing the flavor expressions that occur in coffee cupping, the study turns over a new leaf in research efforts on the relations among language, cognition, and perception.

Keywords: crossmodal expression, flavor, synesthetic metaphor, synesthetic metonymy, synesthetic simile, multimodal metaphor, discourse analysis, perception and language, coffee cupping

Table of Contents

Verification letter from the Oral Examination Committee...i

Acknowledgments...ii

English Abstract...iii

Chinese Abstract...iv

Table of Contents... vi

Figures... ix

Tables ... x

Chapter 1 Introduction ... 1

1.0 Overview ...1

1.1 Motivation and Background Information ...2

1.2.1 Why Crossmodal Expressions of Flavor?...2

1.2.2 Why Coffee Cupping? ...4

1.2 Aims of the Study ...6

1.3 Significance ...8

1.4 Organization of the Study ... 11

Chapter 2 Literature Review ... 13

2.1 Cognitive Mechanisms behind Gustatory Impressions... 14

2.1.1 Simultaneously Combined Imagery from Two Perceptions ... 15

2.1.2 Conveying Flavor Images and Imagery ... 19

2.2 Crossmodal Interactions in Language ... 23

2.2.1 The Metaphor and Metonymy of Intersensory Similarities ... 26

2.2.2 Synesthetic Metaphor and General Regulations ... 30

Chapter 3 Methodology ... 34

3.1 Data... 34

3.1.1 Coffee Cupping and Notes ... 36

3.1.2 Data Retrieval I: Identification of Crossmodal Metaphors and Metonymies (CMMIP) ... 40

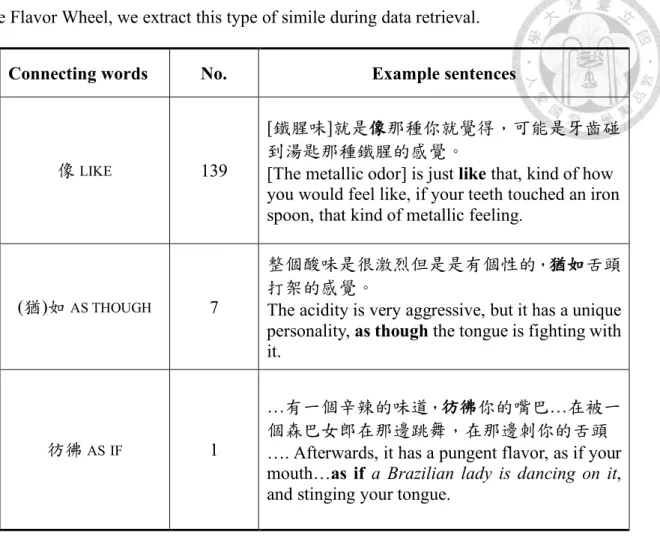

3.1.3 Data Retrieval II: Similes of Gustatory Imagery ... 44

3.2 Method ... 46

3.2.1 Synesthetic Metaphor: Regulation and Directionality ... 47

3.2.2 Foregrounding and Backgrounding: the Zone Activation of Modifiers ... 49

3.2.3 Imagistic Simile: Prototype Effect and Image Schema ... 53

Chapter 4 Synesthetic Metaphor ... 58

4.1 Types of Synesthetic Metaphor ... 59

4.4.1 Flavor is Sight ... 60

4.4.2 Flavor is Sound ... 65

4.4.3 Flavor is Touch ... 66

4.2 Directionality and Proposal ... 68

4.3.1 Directionality and Regulations... 69

4.3.2 Proposal ... 73

Chapter 5 Synesthetic Metonymy ... 75

5.1 Foregrounding and Backgrounding ... 76

5.1.1 Density: Nong and Dan ... 76

5.1.3 Intensity: Zhong ... 86

5.2 MORE IS HEAVY, DENSE, AND THICK ... 89

Chapter 6 Synesthetic Simile ... 92

6.1. Imagistic Mapping ... 92

6.1.1 Narrowing: the Prototype Effect ... 93

6.1.2 Broadening: the Image Schema ... 99

6.1.3 Narrowing and Broadening ... 103

6.2. Crossmodality in Imagistic Similes ... 106

6.2.1 Visual Image, Tactility, and Flavor ... 108

6.2.2 Multisensory Recollection from Flavor ... 110

Chapter 7 Conclusion ... 113

7.1 Recapitulation ... 113

7.1.1 The Shared Mechanism ... 115

7.1.2 Communicative Functions of Synesthetic Expression ... 118

7.2 Implications and Prospects ... 120

References ... 123

Figures

Figure 2.1 Pathways of smell and taste ... 17

Figure 2.2 Hierarchicy of Senses proposed by Ullmann (1959) ... 30

Figure 2.3 Directionality of Senses proposed by Williams (1976) ... 31

Figure 2.4 Modified Directionality of Senses by Werning et al. (2006) ... 32

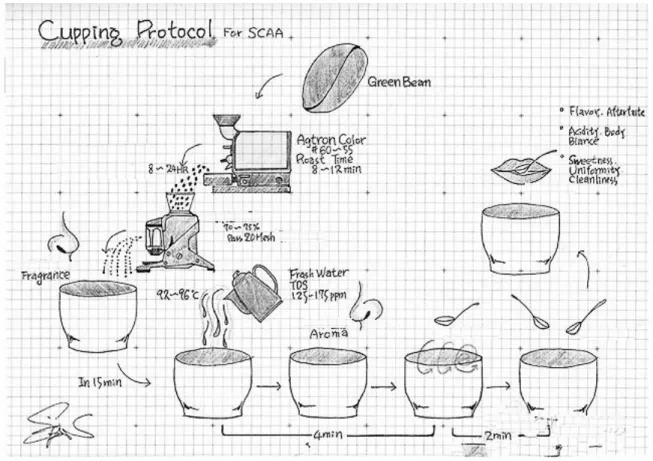

Figure 3.1 Coffee Cupping Protocol From SCAA ... 36

Figure 3.2 Coffee Taster’s Flavor Wheel From SCAA... 38

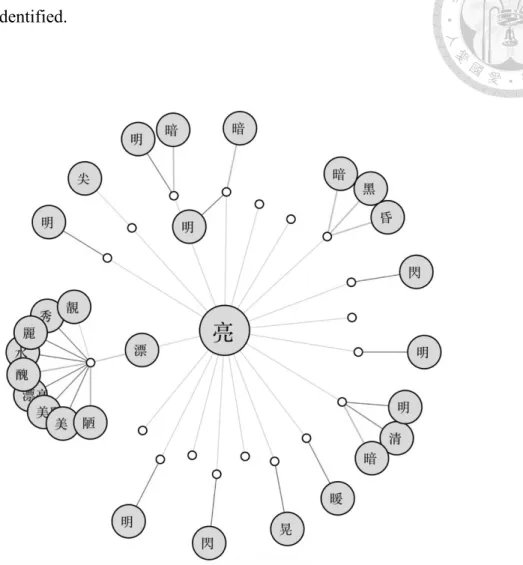

Figure 3.3 The Chinese WordNet of Liang ... 44

Figure 3.4 ACIDITY IS LIGHT proposed by Paradis and Eeg-Olofsson (2013) ... 49

Figure 4.1 Flavor Descriptions in terms of Crossmodal Mappings... 73

Figure 5.1 The Chinese WordNet of nong ... 77

Figure 5.2 The Chinese WordNet of dan ... 80

Figure 5.3 The Chinese WordNet of hou ... 83

Figure 5.4 The Chinese WordNet of bo ... 85

Figure 5.5 The Chinese WordNet of zhong ... 87

Figure 5.6 Synesthetic Metonymy and MORE IS HEAVY, DENSE AND THICK ... 91

Tables

Table 3.1 Connecting Words of Similes in The Cupping Data ... 46

Table 3.2 Zone activation ... 51

Table 3.3 Multi-level taxonomy adopted from Raskin and Nirenburg (1995), Dixon (1982), Givón (1970) and Frawley (2013) ... 52

Table 4.1 Property-Denoting Descriptions in Flavor Expressions ... 59

Table 4.2 Taste and Smell as Target Domains from Williams’ (1967) ... 70

Table 4.3 Taste and Smell as Target Domains from Werning’s (2006)... 71

Table 7.1 Crossmodal Expressions in Language ... 115

Chapter 1 Introduction

1.0 Overview

This study aims to explore how flavor is crossmodally conceptualized and described in Taiwan Mandarin by analyzing the data collected from the professional practice of coffee evaluation. In particular, we explore crossmodal mappings in lexicons at a semantic- pragmatic level so as to understand how synesthetic metaphorical forms are used to capture the intrinsic expressiveness of the flavor percept. Based on the discourse data collected from 10-hour video recordings of coffee cupping practices, we propose three synesthetic metaphorical forms to represent and discuss the crossmodal patterns of perceptual expressions found in the context of coffee tasting and evaluating. We find that the three synesthetic metaphorical forms, that is, synesthetic metaphor, synesthetic metonymy, and synesthetic simile, are strategies utilized by the speakers (i.e., the coffee tasters) to describe the flavors more comprehensibly and to evoke emotional feelings from the audience. The purpose of the present research is to shed light on the importance of crossmodality in the discourse of perceptual descriptions and to pave the way for further studies to be conducted on the expression of flavor in linguistics research.

Our study also investigates the data from a more general perspective, using concepts such as the image schema and the prototype effect from the Idealized Cognitive Model (ICM), and further illustrates the communicative functions of the coffee cupping discourse. In particular, the cupping part of the coffee evaluation procedure is captured to gain a precise understanding of the flavor expressions given during the act of conducting the coffee into the mouth. By analyzing the consequent expressions, we endeavor to explain the perceptual

comprehensibility of the linguistic crossmodal mappings of sensory modalities. In so doing, we will obtain a more comprehensive view of cognition and perception in relation to the conceptualization and metaphorization of flavor.

In sum, this research seeks to determine the prominence of crossmodality in the discourse of describing and expressing perceptual feelings. With data collected from actual coffee cupping practices, this study aims to investigate highly context-dependent synesthetic expressions (i.e., expressions of crossmodal mappings) by proposing three synesthetic metaphorical forms, that is, synesthetic metaphor, metonymy, and simile. By thoroughly analyzing these synesthetic forms and functions within the framework of cognitive linguistics, this research examines the emerging role of crossmodality in the context of flavor expressions stated during coffee cupping. Furthermore, this study seeks to contribute to linguistics and psychology research by clarifying the varied nature of synesthetic metaphorical expressions.

1.1 Motivation and Background Information

In the present section, we introduce the motivations behind studying crossmodality in flavor expressions and explain the choice of collecting Taiwan Mandarin-language data from coffee cupping practices occurring in Taiwan.

1.2.1 Why Crossmodal Expressions of Flavor?

A crossmodal expression entails an intersection of human senses in language (Marks, 1978, 2014). It was firstly derived from multimodal metaphors (Forceville & Urios-Aparisi, 2009), which are metaphors whose target and source domains are each represented mainly and particularly in different perceptual modalities ranging from the basic five categories: touch,

smell, taste, hearing, and sight. To be more precise, crossmodality in language is a subtype of multimodality, and it captures modal convergences and similarities within the sensory perception modes (verbal, visual, taste, smell, etc.) simultaneously though a transformed conceptual structure (Binder and Desai, 2011). In the fields of psychology, communication, and pragmatics, many researches have been conducted to examine topics such as synesthesia (Cutsforth, 1924; Cytowic, 1989, 2002; Day, 1996; Heyrman, 2005; Simner & Hubbard, 2013), synesthesia and synesthetic metaphor (Day, 1996; Gibson, 1966; Lu, 2011; Mandler, 2005; Marks, 1987, 1995, 1996; Miller & Johnson-Laird, 1976; Rodríguez, 2001; Shen, 1997;

Shen & Gadir, 2009; Werning, Fleischhauer, & Beseoglu, 2006; Williams, 1976; Yu, 2003;

Zampini & Spence, 2010), and the influence of crossmodality on flavor expressions (Auvray

& Spence, 2008; Cytowic, 2003; Kontukoski et al., 2015; McBurney, 1986; Mozell, Smith, Smith, Sullivan, & Swender, 1969; Murphy & Cain, 1980; Smith & Margolskee, 2001, March 1; Spence, Levitan, Shankar, & Zampini, 2010; Verhagen, Kadohisa, & Rolls, 2004).

Although examinations of the effects of crossmodal expressions on the communication of flavor are still lacking, previous studies have pinpointed the importance of crossmodality in gaining a richer comprehension of human perceptual feelings.

Past researches of multimodality such as those on multimodal metaphors (Forceville &

Urios-Aparisi, 2009) have also supported the view that crossmodality in language is crucial in communication concerning interactions between different perceptual formations such as in classics literature (Hamilton, 2011; Yu, 2003). This possible achievement of depicting two distinctive perceptions to convey the same perception without any hesitation renders the study of crossmodal expressions crucial to understanding the discourse of perceptual experiences. Moreover, though the consequent metaphorical forms of crossmodality cannot

be cognitively comprehended, the audience can still catch the perceptually indicative meaning and the emotional implication from the discourse.

However, studies of crossmodal expressions have mainly focused on the interactions between sight and hearing, rather than those of smell and taste. The study of other types of perceptual depictions, such as flavor expressions, is thus urgently required. Despite the fact that Taiwanese culture is embedded in food to the extent that the pragmatic daily greeting of the people is “have you eaten?” rather than “hi, how’s it going?” linguistic studies of Taiwan Mandarin flavor expressions are scarce. Furthermore, mappings across distinctive perceptual modalities are comparably rare in daily linguistic expressions. Studies of the linguistic percept of flavor are even scarcer in Taiwan Mandarin. To bridge this research gap, the study examines the crossmodal expressions of flavor as an interactive process of perceptual and emotional communication between the tasters and the audience.

1.2.2 Why Coffee Cupping?

Among professional food critics in Taiwan, coffee cupping is a relatively standard practice of evaluating the flavors of drinks, and has burgeoned in Taiwan in the recent decade. Started in the United States, coffee cupping, owing to its use in standard industry practice, became prevalent in the late nineteenth century (Allen, 2010). Compared with the preparations for the evaluation of cuisine (involving a complicated procedure requiring culinary arts skills) and wine (involving a complex processing of fermentation), the preparations for coffee cupping are more explicit and direct. In a standard coffee evaluation, coffee tasters attempt to measure the important flavor attributes specifically by focusing on tactile qualities, such as the body (e.g., oiliness, slipperiness, smoothness, and roughness), astringency (feeling of

constricting body tissues), aftertaste, acidity, balance, and sweetness, along with a series of standard procedures from roasting and brewing to cupping.

In Taiwan, following the growing trend of tasting and evaluating coffee in public, coffee cupping has shown a considerable prevalence in the recent decade. Coffee cupping was first introduced by the faculty of the Department of Agronomy at National Taiwan University in 2004. For the purpose of assisting the cultivation of specialty coffee beans in Taiwan, the standards of arabica coffee set forth by the Specialty Coffee Association of America (SCAA) were adhered to, instead of those used by major international merchandisers (Wang, 2010).

Since the conducting of coffee cupping has become an annual routine, the world-wide reputation of Taiwan’s specialty coffee beans has also improved (Wang & Lin, 2016).

Moreover, the expression of flavor by coffee tasters during coffee cupping, as evident in their records and notes, is distinct and difficult. The reason lies in the cupping procedure and the standard way of evaluation. During cupping, tasters are asked to comment on the coffee relatively objectively, by giving details in direct connection to an audience’s life experience in order to offer a comprehensive overview. At the same time, cupping practices stipulate a time limit of eight minutes for the tasting of each cup. In other words, there is no extra time for tasters to have a second tasting of the same coffee; they have to offer comments instinctively along with their brief impression of the target coffee. Thus, flavor expressions made during coffee cupping reflect more instinctive human perceptual experiences than the refined food critiques given in publications.

However, linguistic researches on the flavor expressions made during cupping are scarce.

Discussions on “winespeak” seem to be more prominent. In addition, as noted by Caballero (2007), metaphors play an important role in connecting perceptions with linguistic

representations. Crossmodal interactions between taste, smell, touch, and sight can be present in both flavor experiences and expressions (Auvray & Spence, 2008; Caballero, 2007; Marks, 1978). On the other hand, researchers have further suggested that the gap between science and language results in similar but different aspects of the synesthetic phenomenon (Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010; Marks, 1996; Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013).

Unfortunately, none of the researches concerning perceptual expressions mentioned above have been carried out using Taiwan Mandarin-language data. Therefore, this study aims to conduct a thorough examination of coffee critics’ flavor descriptions in Taiwan Mandarin to unveil the mechanisms behind linguistic inventiveness and expressiveness.

1.2 Aims of the Study

The aim of this study is to gain insight into crossmodal expressions of flavor in Taiwan Mandarin through an examination of coffee cupping notes with a focus on bridging the research gap concerning crossmodality in the study of language. To understand the interpretive impact of human linguistic expressions, the present study investigates synesthetic forms (i.e., expressions involving interactions across different types of senses or perceptions), such as synesthetic metaphor (i.e., crossmodal metaphor), synesthetic metonymy (i.e., crossmodal metonymy), and synesthetic simile (i.e., crossmodal simile), adopted in the expressions of intramodal similarity (Marks, 1978: 191). The study is thus taking a deeper look into how these synesthetic strategies reveal the interactive process and perceptual-emotional communication between the coffee tasters and the audience, and how the expressions further contribute to perceptual description studies in the field of discourse analysis. Our research questions under investigation are as follows:

1. How is flavor described crossmodally through language during coffee tasting?

2. How are the meanings of the crossmodal expressions representing the experiences of coffee tasting construed?

3. Why are the transitions from one perceptual modality to other modalities expressed in coffee tasting dialogues?

The first and the second questions analyze how the crossmodality within perceptual descriptions, evident in Taiwan Mandarin flavor expressions, shapes our understanding of flavor by using data drawn from the notes of coffee cupping. Strictly speaking, by adopting a bottom-up approach, we aim to clarify the conceptual and linguistic mechanisms behind the linguistic representation of flavor. Meanwhile, given that previous psychological studies and literatures analyzing crossmodal perceptual experiences have commonly focused on smell and taste, we consider the distinction of perceptions within flavor expressions as an original and essential contribution to crossmodal investigations.

In the last question, we presuppose a cognitive arrangement between language and perception in crossmodal expressions of flavor. This presupposition is motivated by the claim of Auvray and Spence (2008) that the multisensory perception of flavor may follow the unification of the qualities of taste and smell into one simple image or impression. We thus endeavor to reveal, through our data, the miscellaneous facets of flavor in terms of crossmodal interactions, and to discuss further the influence of acquired experiences on the conceptualization of flavor. In the meantime, we aim to examine the effect of culture on Taiwanese speakers’ flavor experiences and expressions.

1.3 Significance

This study examines the crossmodal expressions that engage one of the most primitive perceptions, that is, flavor. Through a reliable and in-depth examination of the data collected from 10 hours of recordings, this study aims to develop a comprehensive understanding of the crossmodality taking place in linguistic performances. At the semantic level, several meanings of perceptual modifiers within certain contexts are developed to reveal the crossmodality in words as well as the metaphorical effect based on the perceptual resemblances and primitive conceptual structures from the ICM. We employ concepts from similar discourse studies on wine reviews and suggest three forms of synesthetic expressions that represent the metaphorical and crossmodal strategies used by the tasters in our data. At the pragmatic level, we investigate the communicative functions of the three synesthetic metaphorical forms created by either the tasters or the audience when expressing their sensations of flavor in detail. A simplified version of the definitions of the three synesthetic metaphorical forms is presented below (for more details on the definition of each strategy, see Chapter 3).

Synesthetic Metaphors: The crossmodal metaphors that involve the perceptual interactions of TOUCH, SIGHT, TASTE, and SMELL are regarded as synesthetic metaphors. Three regulations concerning directionality and tendencies are as follows: (1) the lower (i.e., primitive and lacking sufficient scientific investigation) senses serve the source domain, while the higher (i.e., advanced and well- developed in scientific researches) senses serve the target domain; (2) tactility is the predominant source in terms of the accessibility of crossmodal transfers; (3)

and the transferring directionality is “touch à smell à taste à hearing à vision.”

A modified directionality of crossmodal mappings in flavor descriptions is thereafter proposed in the present study to gain a precise understanding of the linguistic crossmodal interactions of flavor.

Synesthetic Metonymy: Following the definition of synesthetic metonymization established by Paradis and Eeg-Olofsson (2013), the crossmodal metonymies included in the present study are in fact the results of zone activation. Paralleled with the figure-ground effect, two mechanisms are considered as the strategies of this metonymization: (1) foregrounding, meaning the elevation of a certain perceptual aspect from the property modifiers and (2) backgrounding, signifying the inhibition of other perceptual aspects contained in the knowledge of single modifiers. Lastly, the innate conceptual metaphors of MORE IS HEAVY, MORE IS DENSE,and MORE IS THICK are situated in synesthetic metonymies, allowing the accessibility of shifting aspects.

Synesthetic Simile: Synesthetic simile is a form extended from imagistic metaphor, which is also known as image metaphor (Lakoff, 1987b). This involves the application of mental images based on primitive cognitive theories such as the prototype effect (Lakoff, 1987a; Langacker, 1987) and the image schema (Clausner

& Croft, 1999; Lakoff, 1987c). In our findings, synesthetic similes function by gathering and recalling many perceptions from conceptions (i.e., property, event, or subject) when smells and tastes are described.

Using these three synesthetic metaphorical forms, we propose a revised version of crossmodal tendency and directionality, which enables us to find results that contribute to crossmodal expression research. In addition, the analysis provides us with more extensive knowledge of how human perception and cognition are reflected in linguistic descriptions.

For instance, the synesthetic metaphor of ACIDITY IS LIGHT, which evokes a perceptual or emotional similarity between the taster and the audience while utilizing the two modalities of SIGHT and TASTE, is frequently used by tasters, according to the present data (for more details on other frequent crossmodal metaphors that evoke perceptual and emotional empathy between the speakers and the audience, see Chapter 4).

The sensations of smell, taste, and flavor shared by people have long been considered too instinctive, subjective, elusive, and abstract for the instrumental convergence of language to convey. Our study is one of the first to deal with the intricacy of “reconceptualizing perceptual feelings in functions from both cognitive and perceptual perspectives within the context of crossmodality.” Our analyses of synesthetic metaphorical forms demonstrate that the flavor expressions given by all food critics play a crucial role in transforming primitive perceptions into language. In particular, the application of synesthetic metaphorical forms is a unique strategy used by speakers to strike a chord with an audience and achieve their communicative goals.

The identification of Taiwan Mandarin counterparts to English flavor descriptors is rarely possible, while the language of savoring experiences in Taiwan Mandarin is not well studied. Our study aims to examine flavor expressions in Taiwan Mandarin and to gain more perspectives to approach the conceptualization of flavor. Our methodology includes the collection of data from professional coffee tasting trainings (i.e., Coffee Cupping Lesson). In

total, the verbal data of 45 Taiwanese coffee tasters’ descriptions and explanations of the complex flavors of coffee were manually transcribed from the coffee cupping recordings.

In sum, compared with the crossmodal discourse analyses from previous researches, the present thesis advances a significant step in the study of crossmodal linguistic expressions by tackling flavor conceptualizations in Taiwan Mandarin. A thorough literature review reveals that only a few researches are concerned with the metaphorical mappings of flavor as the target domain, and that no linguistic studies comparing flavor and other perceptions in Taiwan Mandarin have been conducted. Besides analyzing metaphors, the present research analyzes synesthetic similes, highlighting their function as expressive and rooted mechanisms. They enable us to go beyond the boundary of time and space. Finally, we reveal the miscellaneous facets of synesthetic metaphorical expressions in terms of their linguistic and perceptual crossmodal transfers.

1.4 Organization of the Study

The overall structure of this study consists of seven chapters including this introductory chapter. The rest of the study is structured as follows: Chapter 2 begins by laying out the theoretical dimensions of the research, and examines how flavor evaluation, synesthetic metaphors, crossmodal and multimodal mapping are analyzed within the cognitive linguistics framework. In Chapter 3, we describe our methodology of data retrieval combined with discussions of the theoretical background. Further, the identification procedures of the crossmodal metaphors and metonymies are discussed.

The next three sections present the findings of the research, focusing on the three key forms of synesthetic metaphor, metonymy, and simile that have been identified in the analysis.

Chapter 4 elucidates the metaphorical metaphors found in the current data of coffee cupping recordings according to the theoretical framework proposed in Chapter 3. Additionally, we re-evaluate the earlier hypothesis of the directionality of linguistically crossmodal mappings, and propose a revised version for understanding flavor expressions in Taiwan Mandarin. In Chapter 5, we will discuss the synesthetic metonymies employed in the expressions of flavor.

In Chapter 6, we will detail the crossmodal interactions of imagistic similes (as defined in Chapter 3). Finally, Chapter 7 summarizes the present study, discusses the implications of the findings for future related research, and offers suggestions concerning issues worthy of further study.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

The purpose of this study is to facilitate a thorough understanding of how crossmodal expressions, which are descriptions of a specific perceptual feeling through the adaptation of other perceptual modalities, illustrate flavor experiences conceptually and metaphorically.

As noted in scientific studies, the crossmodality of smell and taste seems to be unavoidable in the perception of flavor (Auvray & Spence, 2008; Goldstein & Brockmole, 2010). As noted by Auvray and Spence (2008), flavor, meaning a typical perceptual experience consisting of at least taste and smell while eating and drinking, is often viewed as a unified human perceptual modality in perceptual psychology. However, there is a significant lack of focus on the crossmodality of flavor in studies of linguistic expressions. To investigate the connections between language and flavor perceptions, we begin by reviewing the previous researches examining the crossmodal intersections of flavor from the fields of perceptual psychology to cognitive linguistics.

By the same token, considering how flavor experiences are re-conceptualized in linguistics analysis, we reassess the former linguistic frameworks used in crossmodal studies on wine tasting. Wine tasting (or winespeak), which is a professional sensory evaluation of wine similar to coffee cupping, is the most common subject of crossmodal studies in linguistics (Caballero, 2007; Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010; Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013). Records of wine review allow researchers to take a closer look at perception and language not only because of the professionalism of their contents but also because of the richness of their flavor expressions (Caballero, 2007; Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010;

Paradis, 2008; Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013). It is clear that metaphorical strategies are omnipresent within flavor descriptions but are varied in type (Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013).

The present study finds coffee cupping to be another professional practice of evaluating drinks. Similar to those of wine tasting, the evaluation procedures of coffee cupping involve three stages, that is, fragrance, flavor, and aftertaste (Lingle, 2001). Unlike wine tasting, however, coffee cupping lacks adequate investigation in linguistic studies.

Further, we also review the similarities and distinctions among the terminologies describing crossmodal interactions in linguistics. The terms include multimodal metaphor (Forceville & Urios-Aparisi, 2009), perceptual metaphor (Marks, 1995, 1996), and synesthetic metaphor (Shen & Gadir, 2009; Williams, 1976; Yu, 2003). To clarify the

distinctions, we raise the main concerns of the paper. As mentioned by Marks (1996) and Miller and Johnson-Laird (1976), although language and perception do not necessarily carve the world in precisely the same way, their connections are comparably substantial and inseparable. Therefore, the examination of how crossmodal interaction plays a role in discourses in the context of flavor expressions contributes to both perception and language studies.

2.1 Cognitive Mechanisms behind Gustatory Impressions

To unveil how perception and language are intertwined in terms of flavor expressions, we review the analysis of flavor and flavor expressions in science and linguistics, respectively.

Firstly, we endeavor to understand to which perceptual level flavor is discussed in science, that is, whether it is a combination of multisensory feelings, or a single and unified perception.

Secondly, we organize the common points about flavor in science and linguistics by examining how olfactory and gustatory imageries are constructed, building a bridge between psychological perception and linguistic expression.

Last but not least, in order to determine a suitable analytical method for crossmodal expressions of flavor, we revisit certain cognitive linguistics theories of embodied and perceptual expressions, including conceptual metaphors (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980, 2003;

Lakoff & Turner, 1989) and synesthetic metaphors (Marks, 1995; Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013; Yu, 2003) in crossmodal flavor expressions.

2.1.1 Simultaneously Combined Imagery from Two Perceptions

Flavor is an experience of food from a combination of the olfactory system, where we generate the sensation of smell, and the taste system, which obtains five basic taste sensations (saltiness, sweetness, acidity, bitterness, and umami) (Goldstein & Brockmole, 2010). In addition, it has been discovered that these intersensory interactions of flavor are not merely present in smell and taste. For instance, interactions among the senses stimulated by elements such as the texture and temperature of food (Verhagen et al., 2004), the colors (Spence et al., 2010), and the sounds (e.g., the “crunching” sound when eating potato chips) (Zampini &

Spence, 2010) also matter when tasting flavor. Gibson (1966) proposed that flavor perception is enabled by savoring food at the level of perception, the instinctive sensory impression, rather than at the level of sensation, the feeling aroused by the senses. All of these interactions unveil the multimodal nature of our flavor experience (Auvray & Spence, 2008).

Thus, flavor requires numerous interactions between the senses of taste and smell in the act of tasting. In physiological definitions, taste is considered a minor sense as the channel of only a limited number of sensations: sweetness, acidity, bitterness, saltiness, and umami (Chandrashekar, Hoon, Ryba, & Zuker, 2006; Smith & Margolskee, 2001, March 1). Smell appears to constitute a “dual modality” through sniffing (orthonasal olfaction) via the nose

and eating and drinking via the mouth (Auvray & Spence, 2008). However, the two senses of smell and taste are rather neglected and primitive, not because there is a lack of interest but because they are difficult to measure reliably. Although smell (olfactory sense) and taste (gustatory sense) are distinct in their receptors, as their first sensorium for information processing is identical, they are intimately entwined (Goldstein & Brockmole, 2010). As shown in Figure 2.1, chemicals in foods are detected by the taste buds, which are construed by the gustatory sensory cells. When stimulated, these cells will send signals to the thalamus and insula, which belong to the primary taste area, making us conscious of the perception of taste. Likewise, the olfactory mucosa of the nasal cavities, which contains specialized cells, will pick up the odor molecules in the air. Odor molecules stimulate the sensory cells on the receptor organ, and initiate a neural response. Ultimately, messages about taste and smell are converged in the caudal orbital cortex with the gustatory information (sent from the thalamus) and the olfactory information (received from the olfactory bulb), thereby allowing us to detect the flavors of food (Carey, 2005). Additionally, the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), which is situated in the frontal lobes in the brain, is where taste and smell integrate their messages within the nervous system (Murphy & Cain, 1980).

According to the view outlined here, flavor should be defined as the unification of the senses of smell and taste when tasting food, rather than as a synesthetic experience of both senses (Auvray & Spence, 2008). Mozell et al. (1969) showed that it may be difficult for people holding their noses during tastings to identify the substance that they are drinking or eating. The reason is that food evokes volatile chemicals that reach the olfactory mucosa through the retronasal route, which is the passage that connects the oral and nasal cavities. If the nose is plugged, vapors cannot reach the olfactory receptors, thereby eliminating the

olfactory component of flavor (Goldstein & Brockmole, 2010; Murphy & Cain, 1980).

Figure 2.1 Pathways of Smell and Taste

Illustration by Lydia V. Kibiuk, Baltimore, MD; Devon Stuart, Harrisburg, PA

On the other hand, psychological studies have shown that while flavor is perceived as the unification of both taste and smell, it remains analyzable when people attend to each component separately as well. To clarify the complex interactions between taste and smell in flavor, McBurney (1986) suggested that there ought to be a distinction drawn between synthetic and analytic types of flavor perception. Analytic perception occurs when two

stimuli mixed in a solution retain their separate identities and qualities. By comparison, synthetic perception is when two stimuli that have been mixed together in a solution lose their individual qualities and are replaced by a new and distinct (third) sensation. As it turns out, according to McBurney (1986), during the experience of smell and taste, components of

a flavor do not lose their individual qualities of sensation to form a new sensation. Rather, they are combined in order to form a single percept that is an individual impression of both perceptions. It is therefore believed that the multisensory perception of flavor does not necessarily represent a synesthetic experience because the stimuli are not combined synthetically. However, this could simply reflect the unification of the qualities of taste and smell into one simple image evoked by the act of eating (Auvray & Spence, 2008).

Derived from our ability to construct gustatory imagery (i.e., thinking about the taste experience), the image construed by the unification of taste and smell can be regarded as the connecting factor between perception and language. Kobayashi et al. (2004) supposed that people’s gustatory imagery elicits frontal gyri activation in the absence of actual taste stimuli, and that this imagery is related to the retrieval of gustatory information from our long-term memories. In other words, in spite of the fact that flavor contains the instinctive and abstract senses of smell and taste, the instrumental convergence of linguistic expression seems to be embedded in our subjective and elusive experiences and memories. Moreover, the images are not novel inventions but recollections of our past embodiments. Paradis and Eeg- Olofsson (2013) likewise called the transformation of sensory perceptions into language the

“reconceptualization of perceptual feelings.” We analyze and discuss such imagery expressions found in our target data of coffee cupping practices.

2.1.2 Conveying Flavor Images and Imagery

The investigation of flavor is as intricate a task in linguistics as it is in science. Besides its complicity in human linguistic expression, as illustrated in the previous section, the image driven by the gustatory imagery evoked by flavor experiences can be the bridge linking perception and language. As McBurney (1986) indicated that flavor is an individual impression (i.e., the smell and taste components are united in producing a flavor without losing their separate identities and qualities), from an analytic perspective, gustatory imagery thus allows linguistic expression to be both descriptive in conveying distinctive perceptions, and metaphoric in evoking associative images.

“If we want to determinate and name the quality of a smell, we often use terms derived from other sensory systems. Many words for smells belong as well to taste, to touch, to hearing or to sight. Adjectives directly connected to the perception of a smell are generally derived from the associated nouns (odor, stink, smell, whiff). There aren’t very many such words: stuffy, overwhelming, stinking, rotting, penetrating, pungent, fragrant, perfumed, volatile…Does our limited verbal expressiveness in this area have a purely biological or neurophysiological background or is there more involved?”

— Vroon, Pieter Adrianus, Van Amerongen, Anton, and De Vries (1997)

First, linguistic expressions are viewed as either simplified (Auvray & Spence, 2008) or

“deodorized” (Vroon et al., 1997) in psychology. Since there are no primary and sufficiently distinctive qualities from which the olfactory or gustatory experience can be classified into compounds or components (Gibson, 1966), odors are always the names of objects or classes of events, according to Auvray and Spence (2008). Furthermore, Vroon et al. (1997) noted

regarded as “deodorized” because it tended to be intertwined with other perceptions.

On the contrary, the perceiver is able to access an impression associated with his or her experiences derived from a sensation or a pure percept during tasting. Instead of attending to the source object, one can attend to the subjective experience itself. Objects are not detected merely by sensations; subjective memory and object specification are operated by the joint extraction of stimulus information when smelling and tasting (Gibson, 1966). Likewise, the philosopher Henri Bergson stated the following in “Matter and Memory”:

“[T]here is no perception which is not full of memories. With the immediate and present data of our senses, we mingle a thousand details out of our past experience.”

— Henri Bergson (1913)

This notion is echoed in what scientists call the “Proust effect.” The smell and taste of tea and madeleines provoked Proust’s recollection of past events, which he recorded in one of his most famous stream-of-consciousness literary works. As noted in The Oxford Handbook of Oral History (2011), smell or scent, in this sense, has been considered as the memory sense, as it is most likely to stimulate reminiscence. Proust referred to the memories evoked as involuntary. In spite of all of the descriptions of Proust’s smell memories, even if sensory experience is not considered as the domain of analysis and abstract thought, it would remain a traditionally physiological response shaped by partly psychology and partly personal history. It is believed nowadays that perceptions can serve as a mnemonic device or trigger a memory, neither of which is an uncommon experience (Willander & Larsson, 2007).

Therefore, it is not only physiologically evidential, but socially meaningful when perceptions are communicated with people, especially in a linguistic form such as in discourse or

literature. However, the connection of perception with cultures and the humanities, as stated by Howes below, was not viewed with importance until the end of the twentieth century, when the “sensory revolution” declared the study of perceptions to be relevant for the humanities.

“[The senses become] the most fundamental domain of cultural expression, the medium through which all the values and practices of society are enacted.”

— Howes (2003)

In linguistics research, in accordance with the quote from Howes (2003), metaphorical strategies for interpreting sensory experiences are the instinctive devices for mediating human thoughts and primitive perceptions. Marks (1996) proposed that perceptual metaphor is a crucial metaphorical expression; it concerns how language plays a role in perception. As a metaphor mainly focused on perceptual experiences and expressions, perceptual metaphor involves the concepts of perception (from the senses such as sight, hearing, touch, smell, or taste) as the target concepts, and an asymmetrical relation of metaphoric expression (Marks, 1996).

Discussing the variations of metaphor, Kövecses (2010) asserted that human minds and cultures have major roles in generating metaphors and reconstructing the way people see the world. Extracting source domains from a large number of potential candidates, people select the ones that “make intuitive sense” (Kövecses, 2010), namely, those from human experiences, and match them with the target domains. In addition, in contrast to the traditional view of metaphor as simply a rhetoric strategy, the view provided by the Lakoffian- Johnsonian model (2003), that is, the ICM, holds conceptual metaphor to be a crucial

However, conceptual metaphors are not exempt from the identification, organization, and explanation of linguistic representations in contextual contents while providing heuristic information in flavor expressions (Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010). For instance, in wine discourse, metaphors such as WINES ARE HUMAN BEINGS and WINES ARE TEXTILES are used due to personal preferences or verbosity. Thus, an unclear identification is derived from “(i) the close relationship between the source domains in some metaphors (e.g. architecture and anatomy), (ii) the co-evocation of various metaphors by a single expression, and (iii) the fuzzy boundaries between conceptual and synesthetic metaphor (as these types have been defined in the cognitive literature)” (Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010). In other words, although a metaphor offers a solution to these difficulties by providing wine tasting notes with conceptual frames and corresponding lexicons, several problems arise such as a lack of systematic approaches in creatively expanding such entrenched schemas.

Last but not least, as human tasting systems are biologically obligated to be “gatekeepers”

to identify harmful items from harmless ones for survival, flavor experiences are connected to emotional reactions and memories. In other words, to identify the good and bad things that may affect human bodies, the functions of smell and taste are aided by several components

“associated with a past place or event which can trigger memories, and in turn may create emotional reactions” (Goldstein & Brockmole, 2010). Therefore, when it comes to conveying flavor experiences under a certain cultural context, a vivid image description is utilized not only for specifying the sensory feeling, but also for “demanding a great deal of knowledge and experience on behalf of the readers” (Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013). In addition, even if conceptual metaphors are utilized, the ineffability of linguistic codability in depicting flavor (Levinson & Majid, 2014) remains. Connecting crossmodal perception with linguistic

imagery requires the use of precise explanations found within other cognitive linguistic theories.

Notably, as proven in previous literature, similes, which are capable of conveying an abundance of imaginative, dynamic, and vivid information using gustatory imagery, are in fact expressed the most during flavor experiences (Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010; Paradis

& Eeg-Olofsson, 2013). Croijmans and Majid (2016) mentioned that source-based terms are recorded as being applied more frequently by flavor experts, whereas novices use more evaluative words (e.g., “nice”). Similes can be considered as ad hoc descriptions used because of a lack of direct linguistic indication. Unfortunately, similes have been seen as extending beyond the boundary of metaphorical expressions, rendering them too cryptic and intractable for analysis. In order to thoroughly comprehend the crossmodal expressions of flavor in Taiwan Mandarin, the present study endeavors to take on the crucial task of understanding similes in relation to crossmodality.

2.2 Crossmodal Interactions in Language

To understand the linguistic forms and functions of crossmodal metaphorical expressions, we first distinguish between the monomodality and multimodality of metaphors. According to Lakoff and Johnson (1980), a conceptual metaphor requires a target domain and a source domain within the same texts. Thus, we can understand the target concept through related concepts in other fields of thought. However, as recent studies on metaphor have indicated, the Lakoffian definition deliberately avoided mentioning the types of modality through which the metaphors are “transferred” (whether by writing, speaking, or other ways). Thus, Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (2009) proposed another typical type of metaphor, the

multimodal metaphors, which “are metaphors whose target and source are each represented exclusively or predominantly in different modes.” Accordingly, in the examples given by Lakoff and Johnson (1980), the metaphors whose target and source are each represented in the same modes are monomodal metaphors. By contrast, multimodal metaphors are cued in more than one mode (verbal, visual, taste, smell, etc.) simultaneously, referring to not only its semantics in linguistic expressions but also its implied cognitive concepts.

For instance, suggested by Forceville (2002), the simile, CAT IS ELEPHANT, may involve a monomodal metaphor by juxtaposing two animals in the same position, or by portraying a hybrid, contextual simile, and integrated subtype features in a single figure (Forceville, 2005). For instance, presenting an elephant with a “meow” sound, or having another animal ask “cat?” to the elephant (see Forceville and Urios-Aparisi (2009) for more examples of multimodal metaphors) allows the multimodal metaphor to give a verbal cue from the source domain juxtaposed with the target domain. Notably, this multimodal metaphor cues a separate verbal and visual mode. Further, a crossmodal interaction, which Marks (1978) described as an intersection of senses in linguistic expression, is formed.

“Metaphorical expressions of the unity of the senses evolved in part from fundamental synesthetic relationships, but owe their creative impulse to the mind’s ability to transcend these intrinsic correspondences and forge new multisensory meanings. Intrinsic, synesthetic relations express the correspondences that are, extrinsic relations assert the correspondences that can be.”

— Marks (1978)

In terms of morphology, synesthesia is a combination of “together” and “sensation” in Ancient Greek, σύν (syn) and αἴσθησις (aisthēsis). Accordingly, synesthetic metaphor is the

general terminology referring to crossmodality in metaphors, and it is derived from the neuropsychological term “synesthesia” (Marks, 1978, 1987, 2014). In psychology, synesthesia is a neurological phenomenon in which stimulation (of a single sensory or cognitive pathway) leads to involuntary experiences in another sensory or cognitive pathway (Cytowic, 2002; Cytowic & Cole, 2003). According to Cutsforth (1924), “For synesthetes (people who reported to have synesthesia), the picture is the meaning … they visualize the meaning ... images behaved as if they constituted fully conscious meanings.” In other words, because the synesthete’s personal cognition and perception of sight are intimately related, they are able to “perceptually reason.” Thus, cognitive activities such as “emotions, thoughts, and images” are experienced in sensual terms such as through sound, taste, or touch (Cytowic, 1989). Since a study has found that “the most experienced meditators report concept-based or categorical-sensory amalgamations,” the experience of reasoning our way into synesthetic perception can be possible. Common types of synesthetic experiences are divided into two categories according to the number of domains involved, namely, two-sensory (the crossing of two senses) or multi-sensory (the crossing of three or more senses) (Heyrman, 2005).

However, in linguistics, “literary synesthesia” is not an exceptional perceptual experience of synesthetes but a rather common perceptual experience for most people. For example, in the visualization of sounds, higher tones are viewed as smaller than lower tones, low tones are both larger and darker than high ones, and louder tones appear brighter than mild ones (Cytowic, 2003). (Literary) synesthesia represents a perceptual phenomenon, upon which linguistic expression is positioned (Marks, 1996).

Attempting to examine crossmodality in flavor expressions, we review the following analytical mechanisms behind crossmodal interactions, construals of salience, that is,

metonymization (Paradis, 2004, 2008; Paradis & Eeg-Olofsson, 2013), and the identification of synesthetic metaphors (Caballero & Suárez-Toste, 2010; Marks, 1987, 1995; Yu, 2003).

We also examine the general rules and directionality pertaining to crossmodality noted in previous studies (Lu, 2011; Shen, 1997; Ullmann, 1959; Werning et al., 2006; Williams, 1976).

2.2.1 The Metaphor and Metonymy of Intersensory Similarities

In linguistics, synesthetic metaphor is a metaphor that exploits a similarity between experiences in different perceptual modalities (Heyrman, 2005). Both of the domains being linked together are required to involve perception; otherwise, the metaphor would be considered as only weakly synesthetic (Werning et al., 2006). Day (1996) also noted that, compared with synesthesia phenomena in psychology, synesthetic metaphors are much like other metaphors with cultural elements incorporated into the semantic processes, rather than being simply innate and hard-wired for human cognition. Further, Marks (1974) suggested that the intersection of synesthetic phenomena between pitch, loudness, brightness, and size is rooted in the fundamental similarities of physical experiences. Thus, from multimodal and perceptual metaphor to synesthetic metaphor, through metaphoric descriptors, perceptual similarities, and crossmodal equivalences, the abstract knowledge of human perceptual embodiment shown in language becomes more intelligible (Cytowic & Cole, 2003; Marks, 1978, 2014).

As formerly noted, perceptual metaphor reflects how people decode, assess, formulate, and remember figures of thought when perceiving senses in terms of language. In general, perceptual metaphors involve the concepts of perception (from the senses of sight, hearing,

touch, smell, or taste) as the target concepts, and an asymmetrical relation of metaphoric expression mediates the inclusion of other types of perception in this perceptual stimulus.

Thus, the source domain may not be semantically more concrete than the target domain, but is perceptually more comprehensible and representational of human experiences. Synesthetic metaphors, in this way, are a typical kind of perceptual metaphor with crossmodal

equivalence in both domains (Marks, 1978, 2014).

However, the identification and classification of synesthetic metaphors still remain uncertain and vague. Synesthetic metaphors are thus usually regarded as having fuzzy boundaries, especially when applied in the discussion of cognitive poetics. The complicity of human figurative speech may be a crucial reason, for literary synesthesia “is the exploitation of verbal synesthesia for specific literary effects.” Compared with the original concept of synesthesia in science, literary synesthesia “is typically concerned with verbal constructs and not with ‘dual perceptions’” (Tsur, 2008).

Firstly, the vagueness of identification is evident in Yu (2003)’s work, which highlighted the similar and different regulations of synesthetic metaphors in different languages (English versus Chinese). Though previous researches have reached a consensus about the presence of synesthetic metaphors in both poetic and everyday language, Yu’s studies of Chinese focused only on the synesthetic metaphors found in literature, mainly novels and poetry.

Daily or non-literary discourse in Chinese did not appear to feature synesthetic metaphors.

Therefore, the conclusion that Yu’s findings are cross-cultural and reflect the general mechanisms between language and embodiment may be ad hoc. Next, compared to the identification of ACIDITY IS LIGHT as a synesthetic metaphor by Paradis and Eeg-Olofsson (2013), Yu’s identification of synesthetic metaphors involved associative connections more

than it did synesthetic mappings. For instance, in his example cited from the story “Dry River”

by Mo Yan, “The shadows of the crows and magpies skimming over were brushing his face like fine feathers,” which appeals to the sense of sight, the “shadows” of the birds flying over are depicted as “brushing” the person’s face, thereby evoking the sense of touch. This depiction emphasizes the different viewpoints or subjectivity of the audience. In other words, because the audience associates the motion of being brushed by fine feathers with softness and tactility, the audience’s sense of touch is evoked. In this way, the audience stands in the character’s shoes and experiences the feeling of being brushed. If an outsider’s view is considered, namely, by focusing on the appearance of moving fine feathers, the similarity in the shapes between flying birds and moving fine feathers may be foregrounded. As mentioned by Marks (2014), most synesthetic phenomena in language may simply be expressions creatively applying nonsynesthetic analogy rather than synesthetic metaphors.

According to Marks (1996), flavor is usually expressed through catachresis. The words that we express usually represent the objects that produce them metonymically. Compared to metaphor, metonymy is based on the relation of congruity rather than similarity, and the mapping between the source and target domains is within one ontological domain (Kövecses, 2010). Formed in extensions that cannot be classified like metaphors, metonymy relies on an actual and literal association between two components within a single domain. Geeraerts (2010) argued that Conceptual Metonymy indicates a referential likelihood between senses.

Moreover, Kövecses (2010) explained the types of metonymy emerging from the relations of the inter-components of the ICM (Lakoff, 1987a), for example, whole-part metonymy and part-part metonymy.

In studying the synesthetic metonymies expressed by wine critics, Paradis and Eeg-

Olofsson (2013) defined synesthetic metonymization to mean the “foregrounded” perceptual property of an object or event as a metonymy of shifting active zones. Along with Kövecses (2010), who proposed the notion of whole-and-part metonymy, Paradis and Eeg-Olofsson (2013) showed that the WHOLE-PART account is the main approach in the metonymic expression of sensory experiences.

Some cognitive linguists have viewed the components or features as the salient parts of word representation, and the remaining contextual parts as the background (Cruse, 2000;

Langacker, 1987). According to Gestalt psychology, this phenomenon consists of separate degrees of foregrounding and backgrounding, and is named the figure-ground effect (Langacker, 1984, 1987, 1990). Langacker (1990) also asserted that the relationship between semantics and pragmatics is inseparable. Echoing the effect, he determined this metonymic relationship in terms of profile and base. Every word representation is shaped in a certain domain, which contains a concept (profile) highlighting the region or aspect of the domain, and renders the base to be less salient.

Nevertheless, whereas conceptual metaphors seem to have a certain semantic structure of components, the perceptual components of synesthetic metaphors appear to be semantically primitive and non-compositional (Löbner, 2002). The reason lies in the high productivity of the expressions featuring synesthetic metaphors, which requires the construal to be semantically marginally structured. Therefore, in terms of how the comprehension and explanation of synesthetic metaphors and metonymies are generated from human minds, the answers from the previous studies still remain obscure.

2.2.2 Synesthetic Metaphor and General Regulations

Linguistics scholars have found that several directional rules of crossmodality in language contribute to the hierarchy of the senses. However, these regulations vary from study to study.

In the early stage of synesthetic metaphor investigation, Ullmann (1959) proposed a certain hierarchy of lower and higher perceptions, developing the “panchronistic” tendency (see Figure 2.2). He claimed that despite such factors as individual differences in emotional approaches, cultural experiences, ways of reasoning, and literary expressions, there exist some intersections which people of the world have in common (Ullmann, 1959). Proposing that the five categories of human sense modalities are hierarchical from low to high, he determined that three of the five, that is, touch, taste, and smell, are lower, more primitive, and require the least amount of vocabulary in crossmodal mappings. Sound and sight, on the other hand, engage higher-level perceptions. This captures what is called the “panchronistic”

tendency.

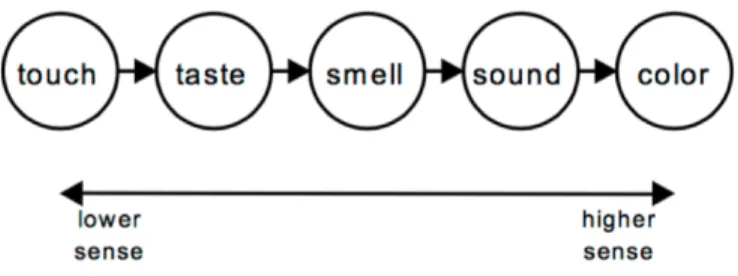

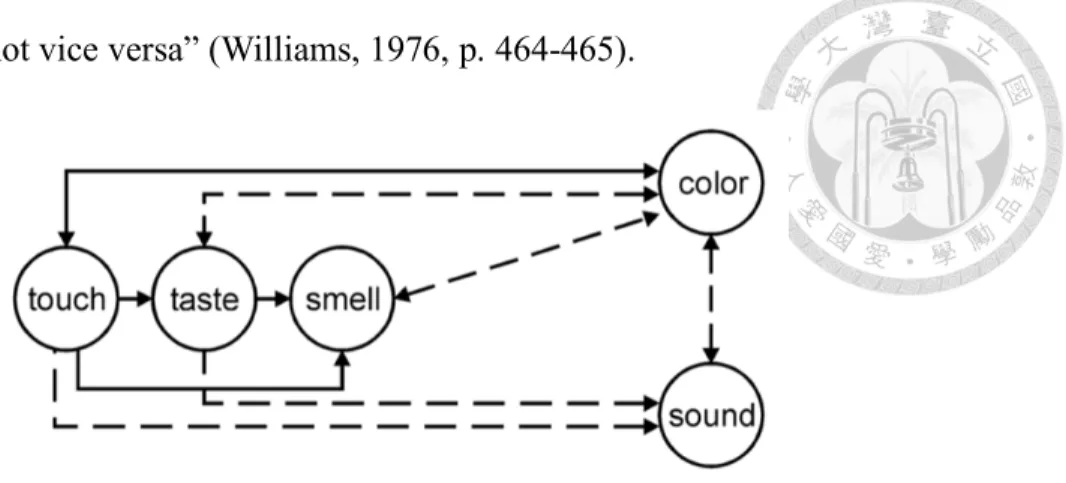

Figure 2.2 Hierarchy of the Senses Proposed by Ullmann (1959) (cf. Werning et al. (2006)

Following Ullmann, Shen (1997) claimed that synesthetic metaphors have a one-directional tendency. Analyzing modern Hebrew poetry, he found a perfect correspondence between the Hebrew data and Ullmann’s (1959) observation of mappings in synesthetic metaphors.

According to Shen, literary synesthesia tends to follow a uni-directional mapping through

different perceptions, much like the mapping of linguistic metaphors within distinctive domains. Furthermore, the directionality obeys the hierarchical sensory relations; according to Shen, “poetic synesthesia systematically prefers to map terms of lower distinctiveness onto terms of higher distinctiveness, rather than vice versa” (Shen, 1997, p. 48). He argued that the distance of contact between the two perceptual domains increases the accessibility of crossmodal mappings. Accordingly, sight and hearing as opposed to smell and taste are of higher distinctiveness due to the wider distance between the perceiver and the perceived. He even conducted an experiment on subjects’ judgments, discovering that the “low to high mapping” is more preferable and “more natural” than the reverse counterpart.

Figure 2.3 Directionality of the Senses Proposed by Williams (1976) (cf. Werning et al. (2006))

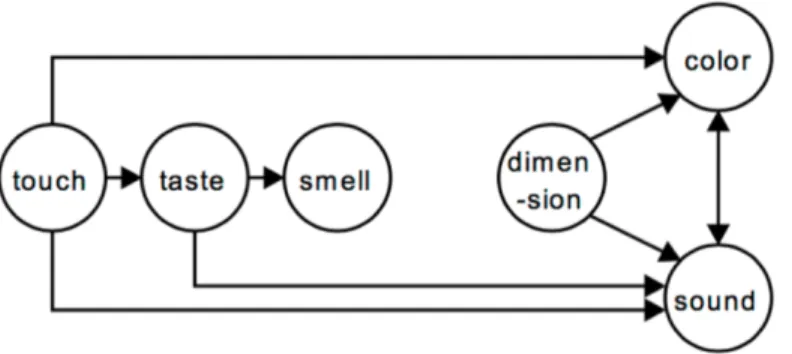

By dividing the sense of sight into two subcategories, namely, color and dimension, Williams (1976) developed a more differentiated claim of directionality. Based on Ullmann’s ideas of directionality, Williams proposed a similar order of sense modalities, but without linearity.

Instead, the senses have a more complex order (see Figure 2.3). Regarding diachronic semantic change, in his investigation of English sensory adjectives, Williams suggested that

“sensory words in English have systematically transferred from the physiologically least