The retention of customer relationships after mergers

and acquisitions

企業併購後之顧客關係維繫

Chen-Yen Yao1Department of Business Administration, Shih Hsin University

Shari S. C. Shang

Department of Management Information Systems, National Chengchi University

Yun-Chen Yu

Department of Management Information Systems, National Chengchi University Abstract: Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) represent a strategic approach for businesses to acquire resources and build competitive advantages. Many studies have investigated the process and results of such resource integration between two firms. Some cases reveal satisfactory results in building asset portfolios, while others uncover downsides after M&As due to conflicts in cultural and system integration. Although the key M&A objective is to expand business operations in providing customers with superior products and services, limited understanding exists in regards to how companies retain the quality of post-merger customer relationships. The research questions of this study are: (1) Do enterprises retain the same quality of CRM after M&A? and (2) How do organizations retain the quality of Customer Relationship Management (CRM) after M&A? To answer the first research question, we collected data from eight banks that underwent M&As in Taiwan from 2004 to 2011, to examine their CRM performances. To answer the second question, we conducted five in-depth case studies from successful and failed CRM cases to understand the important factors about managing CRM during and after M&As. The results find critical and additional influential factors about maintaining and enhancing CRM quality after M&As. These results highlight the importance of measuring and managing CRM during and after a merger and contribute to organizations that plan to develop effective plans for building synergy in CRM after M&As.

1

Corresponding author: Department of Business Administration, Shih Hsin University, Taipei City, 116 Taiwan, E-mail: cherry@cc.shu.edu.tw.

Keywords: Mergers and acquisitions, Post-merger, Customer relationship management, Credit card services

1. Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) refer to situations in which two or more companies combine into one. M&As activities involve the integration of company entities, functions, subsidiaries, systems, and other resources (Ojala, 2005; Samet, 2010). There were 4,066 merger deals worth $379 billion in 1988 globally and 12,356 merger deals worth $1.63 trillion in 1998 (Rappaport and Sirower, 1999). In the 1990s, companies engaged in cross-border M&As due to globalized industry deregulation (Platt, 2004), while in the 2000s, enterprises conducted M&As to gain various resources including financial capital, core assets, technology, skills, channels, market position, knowledge, and other capabilities (Al-Laham et al., 2010). Companies can build economies of scale, reduce costs, provide new products, and expand their customer base after M&As (Holliday, 1995; Pautler, 2003; Shrivastava, 1986; Tompkins, 2005; Weber and Dholakia, 2000).

Some M&A cases exhibit strategic achievements and improve performance in product profile and customer services and create a stronger market position. For instance, Walt Disney Corporation bought Capital Cities/ABC in 1995 to expand its distribution systems. The sale included filmed entertainment, cable television, broadcasting, and telephone communication to provide a full spectrum of services to customers (Ramaswamy, 1997). This M&A led Disney’s shares to rise from $1.25 to $58.625 in 1995 (Fabrikant, 1995). IBM acquired Lotus in 1995 to provide a wider range of applications including spreadsheets, word processors, and a database manager to attract customers in the small-and medium-enterprise market. The 1998 merger between Chase Manhattan Bank and Chemical Bank in 1996 expanded branch services into more than 50 countries (Euromoney, 1997) with an estimated cost savings of $1.5 billion. RTMS and Customer Insight Company (CIC) completed their merger in 2000 to provide solutions for Customer Relationship Management (CRM) (Business Wire, 1999). Moreover,GE Capital Services made more than 100 acquisitions from 1993 to 1998, resulting in a 30% increase in its workforce, a rapid

globalization of businesses, and a doubling of net income (Ashkenas et al., 1998). Thermo Electron Corporation, Sara Lee Corporation, and Clayton, Dubilier & Rice grew dramatically and captured sustained returns of 18% to 35% per year by making nonsynergistic acquisitions (Anslinger and Copeland, 1996).

There are, however, unsuccessful M&A cases. The majority of corporate M&As do not produce increased revenue and profits, because the merged organization fails to adequately leverage the combined organizations' strengths (Bressler and McDonnell, 2007). Fifty-seven percent of merged companies’ returns to shareholders lagged behind the average for their industries (Ashkenas

et al., 1998). Novell, Inc. acquired WordPerfect Corp. in 1994 with the hope of

increasing its product offerings with word processing capability (Harper, 1998). Novell’s key product launches fell behind schedule. WordPerfect’s sales sank 17% in 1994, and Novell’s performance and stock price dropped sharply (Vestring et al., 2004). Another case was BMW’s acquisition of Rover in 1994. BMW expected to enter the smaller and lower-budget car markets with small production costs (Coursework.info, 2006). The merged company ended up losing

$6 billion over six years (Andrews, 2000). In 1996, Wells Fargo acquired First

Interstate Bank, expecting to increase their customer base and service lines. Due to customer data loss, system problems on the front line, and labor issues in the back office, lost customers. Its stock price dropped, and the company experienced a $180 million operational loss in one quarter (Anthes, 1998).

Many researchers focus on the determinants of M&As success (Ahmadvand

et al., 2012; Darkow et al., 2008) or the advantages or risks of M&As (Brakman et al., 2013; Neary, 2007). After a merger, a major disconnect immediately

emerges due to the lack of integration between the relationship networks of the two formerly independent firms (Bressler and McDonnell, 2007). The benefits of M&As are not only in gaining resources, but also retaining customer relationships; however, there is limited understanding about how companies retain the quality of customer relationships during and after M&As. The research questions of this study are as follows.

(1) Do enterprises retain the same quality of CRM after M&A? (2) How do organizations retain the quality of CRM after M&A?

To achieve these research objectives, we applied a resource-based view to verify the kind of intangible resources that customer relationships need in order

to stay together after a merger and how companies manage the combined resources. We first reviewed and consolidated the concepts of M&As and CRM in M&As. We then collected data from eight banks that experienced M&As in Taiwan during 2004–2011 to compare CRM performance in their credit card business. In addition, we conducted five in-depth case studies to understand the important factors about managing CRM after M&As. The paper concludes with a discussion of the main results and managerial implications.

2. Literature review

2.1 A resource-based view of M&As

Resources are company specific and involve all assets, capabilities, organization processes, information, knowledge, financial or physical assets, and human capital used to transform inputs into a production process (Amit and Schoemaker, 1993; Barney, 1991; Grant, 1991). Firms need to construct resources that are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and non-substitutable to generate the competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). However, resources include both tangible and intangible assets that strengthen or weaken a firm (Wernerfelt, 1984). Chen and Wang (2014) considered a stronger external resource complementarity and stronger internal resource similarity between the acquirer and target firms, which would make integration in cross-border M&As less risky. Wiklund and Shepherd (2009) found alliances and acquisitions bring limited benefits to firms unless a deliberate effort is devoted to resource combination.

Human, organizational, managerial, regulatory, financial, and cultural aspects can affect M&As (Marks and Mirvis, 2011; Worthington, 2004). Furthermore, asset size and quality, management ability, earnings, and liquidity significantly also influence M&As (Worthington, 2004). Five hard factors for successful M&As are a professional target search and due diligence, a realistic assessment of synergies, the right mix of financial sources, a detailed post-acquisition integration plan already prepared in the pre-deal phase, and its speedy implementation (Bertoncelj and Kovac, 2007). In addition, there are five soft factors for successful M&As, including a new combined organizational culture, a competent management team, innovative employees, efficient and

consistent communication, and a creative business environment. Moreover, a coherent integration strategy, a strong integration team, communication, speed in implementation, and aligned measurements are all critical components of mergers (Epstein, 2004). M&As success is a function of strategic complementarity, cultural fit, and the degree of integration (Bauer and Matzler, 2014). Cost and profit efficiency can further evaluate post-merger performance (Koetter, 2008). Typical determinants of M&As for the banking industry are size, profitability, leverage, liquidity, and bank growth (Beccalli and Frantz, 2013).

2.2 CRM in M&As

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) refers to enterprises extensively employing information technology, particularly database and Internet technologies, to understand customer characteristics and track customer behavior in order to provide appropriate products and services, satisfy customer requests, directly communicate with customers, and maintain a satisfied and profitable customer base (Chen et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2005; Wu, 2010). It is vital for companies to coordinate all service functions, automate customer-service operations, restructure business processes, and present a unified view to customers (Bull, 2003; Chattopadhyay, 2001; Karimi et al., 2001). Therefore, the purpose of CRM is to acquire more customers, generate more from customers, and retain highly loyal customers (Hosseini et al., 2010).

With continuous communications and interactive activities, businesses accumulate knowledge on customer preferences and consuming behavior. Based on analyzed customer data, businesses provide services and products tailored to customers’ changing needs and offer customized services that fit customer shopping behavior (Zeithaml et al., 1990). By fulfilling customer needs and cross-selling products or services, businesses increase customer contributions. Companies acquire and retain customers by providing quality services and innovative products (Conway et al., 1999; Levesque et al., 1996; Xu et al., 2002). Reichheld et al. (1990) reported that businesses could boost profits from 25% to 85% and increase company competitiveness by reducing 5% of customer defections. On the other hand, customers can easily switch companies, because of unpleasant customer service or defective products or systems (Childs, 2007; Samet, 2010).

Some M&As projects succeed, because of better customer data integration, service refinement, and strategic planning for merged services (Kotler, 2006; Raman et al., 2006; Rigby et al., 2002; Weber & Dholakia, 2000). For instance, during the merger between Chase Manhattan Bank and Chemical Bank, clients were kept informed about every decision. As a result, there was no fall-off in clients, revenue, or business (Euromoney, 1997; Ramaswamy, 1997). The banks emphasized customer relations in the strategic planning process to reduce obstacles during customer data integration. Through word-of-mouth, customers quickly shared positive or negative opinions about their service experience (File and Prince, 1992; Hofstede, 2001; Siddiqi, 2011). Therefore, companies intending to engage in M&As must carefully review the merged customer profiles and plan an effective strategy to retain and acquire customers.

2.3 Managing M&As projects for maintaining customer relationships

Past studies have addressed the challenges and difficulties of M&As, analyzing such projects from the perspective of pre-merger activities, merging strategies, and post-merger implementations. Many studies have discussed the successful or failed factors of M&A cases (Davidson, 2011; Harper, 1998; Levine, 2011; Mayoff and Cherba, 1998). By focusing on post-merger results, this study identifies six critical factors for managing M&A projects in terms of CRM.

2.3.1 Strategy for rebuilding customer Bbase and service portfolio

Business strategy generally refers to a company’s goals and directions for integration. The strategic calculation and implementation of an M&A can greatly affect subsequent firm results (Hill, 2013). There are two sets of strategies that firms need to scrutinize in order to make a smooth transition in customer services, post-merger. The first strategy concerns refining and maintaining the customer base. The planning session provides a chance to consider the quality of the merged customer base. Companies typically plan for the removal of bad-quality customers and the retention of good-quality customers. This assessment provides the opportunity for understanding customer characteristics and planning for effective promotion and customer communication. The second strategy concerns refining and maintaining products and services. In accordance with customer

profiles, it is also important to assess the portfolio of merged products and services and the refinement of the products and services, post-merger (Goff, 1999). Firms may lose customers after a merger due to a reduced quality of products and services.

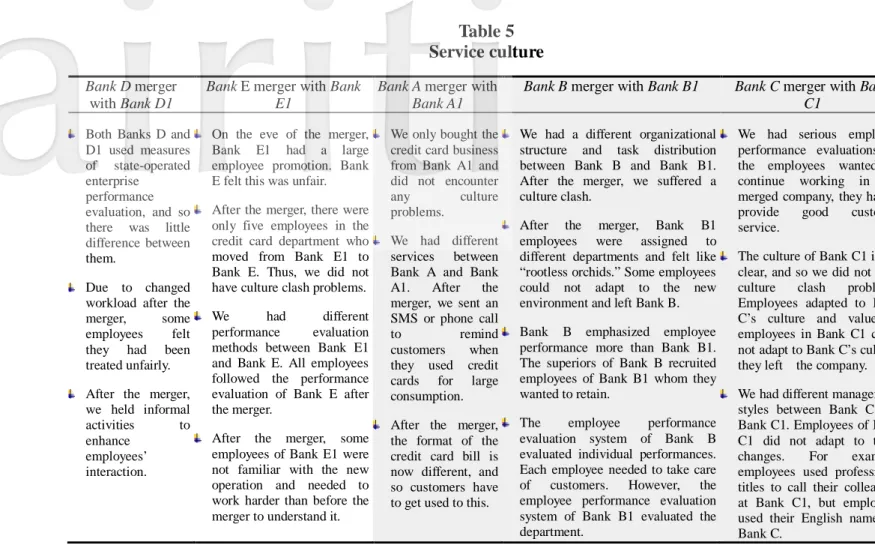

2.3.2 Service culture

Culture refers to an organization’s set of expectations for employees (Hofstede, 1980). A service culture is defined as a customer-centric culture. High service-culture organizations strive to develop service competencies in order to exceed customer expectations and create superior value to attract and retain customers. The expected performance outcomes of a service culture involve increases in product quality, market performance, and customer satisfaction (Beitelspacher et al., 2011). However, due to a lack of standard service quality and service guidance, the post-M&As merged service force may provide inconsistent services. Companies may also display inappropriate attitudes to new customers (Gotschall, 1998). For example, one merged firm may use revenue generated to measure customer services while the other firm focuses on customer satisfaction. The merged firm service providers may respond differently when faced with unhappy customers and may need resources to provide solutions (Harper, 1998).

Cultural clashes are mostly caused by differences in organizational values, management style, and working patterns (Harper, 1998). Different strategies and customer service orientation could lead to serious cultural differences between two companies. In order to maintain their own interests and communication service modes post-merger, the two firms may experience clashes that could lead to reduced employee productivity, responsiveness, or innovation (Marks, 1997; Mayoff and Cherba, 1998). Both companies tend to protect their own way of customer communication and problem-solving approaches. This makes it difficult for the merged companies to serve customers that are used to previous products and services. The cultural clash may also be underlined by different performance expectations. Post-merger employees may experience difficulties in adjusting to different forms of performance evaluation (Harper, 1998). Furthermore, the cultural conflicts could cause customers to experience unstable or inconsiderate service. For example, when Novell, Inc. acquired WordPerfect

Corp. in 1994, it experienced cultural and cognitive clashes. The two companies had fundamentally different ideas about customer service and had many internal arguments (Harper, 1998). The results led to lower service quality and alienated customers (Vestring et al., 2004).

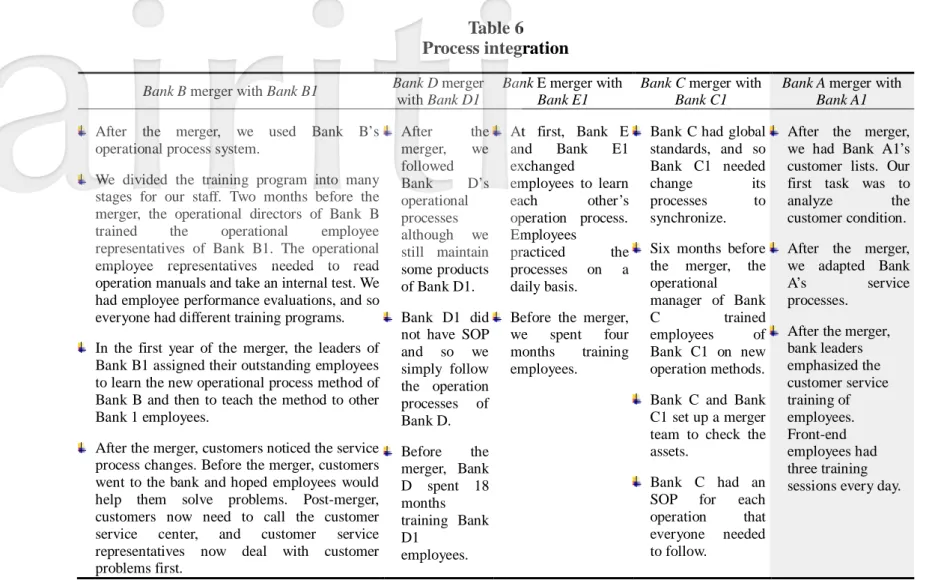

2.3.3 Process integration

Process integration for a business merger requires a thought-out plan to provide similar or improved services to customers (Pai and Tu, 2011). An integrated system can support and enforce the standardization of data and processes within the merged firm (Shang, 2005). Such a system includes business policy discussions, dataflow synchronization, and procedure standardization to provide consistent services to customers. Moreover, the integration process may become an opportunity for the merged organization to strengthen its capabilities for a better competitive position (Robbins and Stylianou, 1999). To ensure customer satisfaction after M&As, the merged firms need to make more efforts to serve customers in a convenient and reliable way to capture customer information (Salami, 2008; Xu and Walton, 2005). For instance, Wells Fargo Bank acquired Norwest Corporation in 1998 with a focus on customer service and planned several ways to integrate processes and maintain customer service quality.

Because the customer base increases after mergers, companies need to emphasize convenient customer service. A successful M&A transition should avoid errors from different business process methods (Alsmadi and Alnawas, 2011). It is therefore important to standardize integrated processes, remove redundant items, and build a synchronized practice in serving customers (Childs, 2007). Employee familiarity with the new operations is also important for process integration. Employee training of new processes can avoid customer confusion and increase responsiveness.

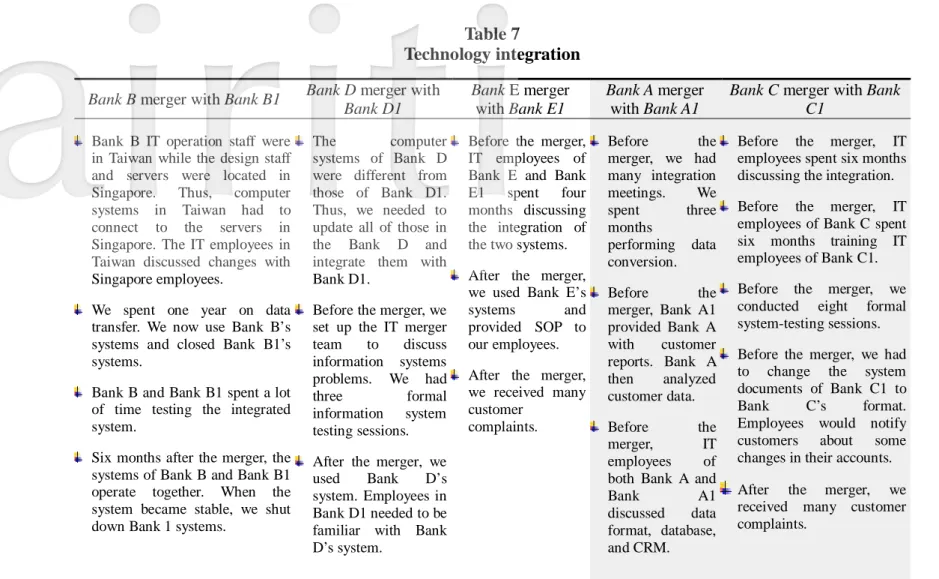

2.3.4 Technology integration

An integrated system provides quality information and increases user satisfaction after mergers (Alaranta, 2005). The first task of system integration is database conversion. Losses or errors in customer data during a system conversion may cause customer dissatisfaction. Slow and inflexible data access

may create inconveniences for customers. For instance, when Wells Fargo acquired First Interstate Bank in 1996, Wells Fargo could not access employees and customers’ data in First Interstate Bank (Hiltzik and Mulligan, 1996). Millions of dollars in deposits were entered into the wrong customers' accounts and direct deposits were delayed. Checks took weeks to clear, an automated telephone banking system failed for several days, and data losses caused a large decrease in the customer base. As previously mentioned, the bank lost $180 million in one quarter, because of problems in system integration (Anthes, 1998). The merging of inconsistent infrastructures may cause system clashes and low operational performance (McKiernan and Merali, 1995). In most M&A cases, the two firms possess different technology infrastructures with a variety of support from different partners. These differences can cause operational delays, loss of opportunities, and decreased revenues (Harrell and Higgins, 2002). As such, companies need to learn the other company’s system to build an effective plan for technology integration.

2.3.5 Communication with customers and employees

Communication with customers and employees is always an important task in all business projects. Communication with both employees and customers of two merged firms is especially important to smooth the transition and reduce uncertainty. Miscommunication regarding the business plan, business expectations, and progress of the project may decrease employee morale and increase the customer attrition rate (Atkinson, 2004). Clear communication with employees of both companies can prevent operational errors and negative attitudes toward work. To help employees respond to multifaceted changes, sufficient communication is key for a successful transition to build employee confidence in the merged company (Davidson, 2011; Xu et al., 2002; Wu, 2010). Communication with customers about the M&As process and assuring them of the same rights and service quality post-merger can reduce business operation confusion (Davidson, 2011). Communication can also help customers understand the company strategy and future plans by increasing customers’ satisfaction (Davidson, 2011; Wu, 2010; Xu et al., 2002). Customers feel respected and valued when they are treated as individuals.

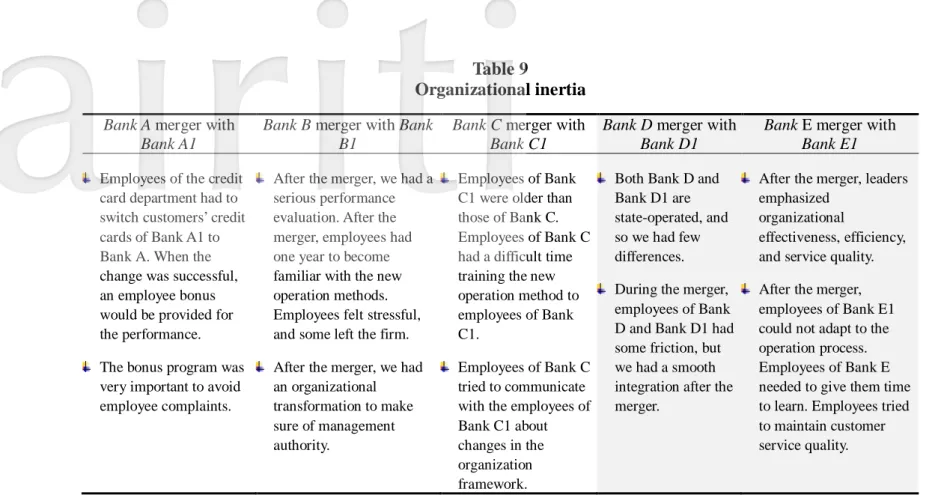

2.3.6 Organizational inertia

Business integration systems drive dramatic changes in both daily operations and critical decision making (Shang, 2005). Employees may manifest resistance through sabotage, vocal protests, attitudes, withdrawal, or reduced commitments (Hultman, 1979). These resistance behaviors may lower productivity, lower the quality of services and goods, and raise the cost of production (Hultman, 1979, 1995; Judson, 1991; Odiorne, 1981). Individuals who are resistant to the changes may intentionally or unintentionally attack the new processes of the IT-enabled changes, thus reducing productivity and/or quality by passive uncooperative actions (Marakas and Hornik, 1996), such as neglecting or delaying work assignments, showing a reluctance to learn new knowledge and skills, refusing to cooperate with other employees, or making careless mistakes (Judson, 1991; Hultman, 1979, 1995; Odiorne, 1981). As another act of passive resistance, employees may devise creative “workarounds” that produce a sense of re-skilling to counter de-skilling of the new system (Alvarez, 2008). Employees may accept lower quality when they have difficulties in adapting to the changes (Hultman, 1979). Therefore, organizational inertia can cause delays in responding to customer requests, deficiencies in services, and decreasing efforts to understand markets and customers to improve products and services.

3. Research methodology

To answer the first research question (“Do enterprises retain the same quality of CRM after M&A?”), we longitudinally tracked CRM performances of M&A cases in credit card services. To answer the second question (How do organizations retain the quality of CRM after M&A?”), we conducted multiple case studies.

3.1 Empirical data collection

Merger-and-acquisition activities have increased rapidly in recent years. In Asia, they have mostly occurred since the 1997 Asian financial crisis (Wong and Cheung, 2009). Governments promoted M&As and stockholders positively reacted, hoping their invested firms could upgrade their competitive ability and

reduce costs in order to increase revenue. In 1990, Taiwan allowed the privatization of commercial banks. The Taiwan government started to promote M&A activities in the financial industry by approving the Finance Holding Company Law in 2001. Mergers and diversification in the financial industry may increase banks' profit margins (Tan, 2009). Since 1990, M&As have been popular in the finance industry. Because consumer banking is more closely connected to customers’ daily activities than corporate finance, most banks have established customer-service centers to serve retail customers as well as CRM functions to trace customer behavior so as to react to product sales, product development, and marketing functions. Therefore, this study focuses on credit card services in consumer banking

We collected data from government published reports on credit card services in Taiwan from 2004 to 2011. We choose eight M&As cases and analyzed CRM performance data one year before and after the declared date of the merger. The reason for analyzing data one year after the merge was to ensure that we eliminated the effects of post-merger turbulence such as refinement of the customer base, clearing out customers with bad credit, and learning about the new customer base. Taiwan’s Financial Supervisory Commission was established in 2004 to provide unified financial supervision after the passing of the Finance Holding Company Law in July 2001 (Tan, 2009). This Commission provides monthly data on credit card performance and CRM indices of credit card services. Four CRM measures were used to measure the CRM performance of credit card services before and after a merger that included customer growth, customer loyalty, customer retention, and customer contribution. Table 1 lists the indices and their calculation.

Customer growth refers to a company’s efforts to acquire customers, representing the company’s marketing strength to obtain new customers and maintain existing customers. Market share, total cards issued, and the number of effective cards measure customer growth in the credit card industry. Customer loyalty refers to customers’ continuous use of the service, which is measured by the return on investment and the number of customers using credit cards. Customer retention refers to a company’s efforts to retain customers, which is measured by the customer attrition rate. Finally, customer contribution means a company’s efforts to promote products/services to customers, such as

Table 1

CRM measures in credit card services

CRM measures Indices Calculation

Growth .Cards issued .Effective cards .Market share

.Cards issued

.Effective cards = total cards issued – total cards cancelled

.Market share = effective

cards/effective cards of all banks Loyalty Active cards Active cards

retain Attrition rate Attrition rate = cards cancelled/cards issued Customer

contribution

.Revolving balance per card .Balance per card

.Revolving balance per card = revolving balance/effective cards .Balance per card = retail sales

volume/effective cards

cross-selling to gain more customers’ pocket-share, which is measured by a card’s revolving balance. Card issuers’ can earn interest on the debt of customers’ revolving balance. The card balance refers to the use of the credit card to buy products or services, which is measured by customer preferences for using the services. We selected eight M&As cases of credit card services from 2004 to 2011 (see Appendix 1 for selected cases).

3.2 Multiple case studies

The case study approach is appropriate for providing perception and answers to the questions of “how” and “why” (Yin, 1994). This study also focused on gaining knowledge of M&A in reality through the study of social construction (Klein and Myers, 1999), which provides an interpretive and explorative view. The multiple case design induces a more accurate, generalizable, and robust theory than single-case studies and yields elaborate but also idiosyncratic accounts (Eisenhardt, 1989; Yin, 1994). With this in mind, based on the six critical factors of managing M&As projects for CRM, we conducted an analysis on the five selected banks (Table 2). We chose five typical cases to examine the

factors for implementing CRM that resulted in success or failure. The cases include two with improved CRM performance one year after the M&As, two with decreased CRM performance one year after the M&As, and one with the same performance.

We also conducted a semi-structured questionnaire for this study. Appendix 2 presents a summary of data collection of the five banks. We contacted multiple interviewees from all five banks for data collection, and the case study was extended from January to June in 2014. Managers who went through M&As were the major interviewees. Five to six business managers were interviewed for each case, and every interview lasted more than an hour. Interviewees were encouraged to think retrospectively about CRM conditions before and after the merger.

We also collected archived data including business publications, Internet sources, promotion materials, industry reports, annual reports, and company documents. The filed notes from these observations were used to verify and elaborate upon the interview data. Data analysis was performed via transcription, triangulation, and interpretation. Our data analysis followed an iterative process of moving back and forth between our conceptual framework and data. Six critical factors that included the strategy for rebuilding a customer base and service portfolio, service culture, process integration, technology integration, communication with customers and employees, and organizational inertia were discussed in-depth and analyzed to clarify characteristics and influences. Lastly, we examined the results and collaboration so as to consolidate and verify patterns to form our final findings.

Triangulation of data from multiple sources strengthens the robustness of the findings (Eisenhardt, 1989). To highlight reliability and validity issues, two research partners were invited to independently code the data to enhance inter-rater reliability, and member checking was conducted on the five banks to ensure validity (Miles and Humerman, 1994; Riege, 2003).

4. Research results

4.1 Empirical results

Table 2

Critical factors from managing M&As projects for CRM

Factor Description Sub-items Author(s)

Strategy for rebuilding customer base and service portfolio

The company’s goals and directions of business integration of customer base and diversity of services. Customer base refinement Childs (2007); Levin (2011) Service portfolio refinement Childs (2007); Levin (2011) Service culture Organizational

expectations for employees to develop service and performance competencies to attract and retain customers.

Standard of service quality

Harper (1998) Service attitude and

behavior

Harper (1998) Management style Harper (1998) Performance measurement Harper (1998) Process integration To build standardized data and processes within the merged firm.

Process standardization van de Vliet (1997) Operation familiarity van de Vliet (1997) Technology integration Technology integration to avoid inconsistent data and cut costs.

Database conversion

Mayoff and Cherba (1998)

System/ dataflow synchronization

Mayoff and Cherba (1998)

Business policy discussion,

Mayoff and Cherba (1998)

Procedure standardization

Mayoff and Cherba (1998)

Communication Communication with both employees and customers to smooth the transition and reduce uncertainty in the changing period.

Communication with employees Davidson (2011) Communication with customers Davidson (2011) Organizational inertia Employees may manifest resistance through different kinds of behavior due to business-integration projects.

Low productivity McKiernan and Merali (1995) Low quality of services McKiernan and Merali (1995) Low intention to cooperate McKiernan and Merali (1995) Low intention to innovate McKiernan and Merali (1995)

services before and after the mergers that included customer growth, customer loyalty, customer retention, and customer contribution. The CRM performances after M&As of the eight selected credit card services are summarized in Table 3. The symbol “+” indicates improved performance a year after the merger, the symbol “−” represents decreased performance one year after the merger, and the symbol “≈” shows performance remaining the same a year after the merger.

“Effective Cards” represent the credit card issuer’s capability to acquire customers. For example, the number of effective cards in HSBC after the acquisition of The Chinese Bank is lower than the total effective cards of the two banks before the merger. The effective cards continued to decrease six months after the merger. One year after the merger, the effective cards remain lower than the sum of HSBC and Chinese Bank. Therefore, we use the symbol “−” to indicate the decreased customer acquisition. In addition. Active Cards” indicate customer loyalty. In the case of Citibank’s acquisition of the Bank of Overseas Chinese, there was a growing trend of active cards for more than six months after the merger. We use the symbol “+” to indicate the improved performance of active cards. Appendix 3 and Appendix 4 present the data of credit cards issued after the mergers as well as post-merger market shares.

By analyzing the performance of the eight banking M&A cases, we find three cases of decreased CRM performance, two cases of improved CRM performance, and three cases that remain the same one year after the respective M&A. We then selected five banks for in-depth case studies, including Taiwan Cooperative Bank, Taishin International Bank, Citibank, HSBC, and Bank of Taiwan.

4.2 Summary of qualitative results

This study conducted five in-depth case studies in order to answer the second question: How do organizations retain the quality of CRM after M&A? Tables 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 present the six critical factors that include: strategy for rebuilding a customer base and service portfolio, service culture, process integration, technology integration, communication with customers and employees, and organizational inertia for managing five banking M&As projects in regards to CRM. Due to privacy considerations, we used a code name for the study.

Two cases of improved CRM performance Three cases of decreased CRM performance Table 3

Credit card service CRM performances post-M&As Growth Loyalty Retain Customer

Contribution M&As Cases Cards issued Effective cards Market share Active cards Attrition Rate Revolving balance per card Balance per card Standard Chartere d Bank ≈ − − − + − − Taiwan Coopera tive Bank ≈ − + − − − − Taishin Internati onal Bank + ≈ ≈ ≈ + − − Citibank + ≈ + + + + ≈ Taipei Fubon Bank − − − − ≈ − − HSBC − − − − − − − Bank of Taiwan − − − − ≈ − − Far Eastern Internati onal Bank ≈ − ≈ ≈ − − −

Table 4

Strategy for rebuilding a customer base and service portfolio Bank A merger with Bank A1 Bank C merger with Bank C1 Bank B merger

with Bank B1

Bank D merger with Bank D1

Bank E merger with Bank E1

Customers recognized that brand identification is the major value of Brand A. We evaluated the value and

customer consumption of Bank A1. Accordingly, we examined customers’ financial resources.

We provided credit cards to valuable customers and then focused on potential customers of Bank A1. We held a credit card consumption campaign. We hoped that customers would use our credit card to earn customer loyalty.

After the merger, we traced the promotional activities of Bank A1. We then analyzed customers’ daily consumption report and found the customer contributions of Bank A1 were low. Therefore, there was a lack of merger efficiency.

We analyzed products and services of Bank C1 to understood customers’ usage. After the merger, we communicated with customers regarding their lower contribution rate to Bank C1. We noticed if customers did not interact with us and we would close the current account. After the merger, we categorized wealthy

or high-asset customers. According to their regions, we notified nearby branches to be active in providing our fortune management service.

We analyzed the information systems of Bank C and Bank C1. We then understood the valuable products of Bank C1 to make up any deficiency of Bank C.

After the merger, Bank C did not provide deposit books for their customers, and some branches were closed. Customers

considered that this was very

inconvenient.

At first, customers had high expectations of Bank C due to the brand. However, the main business of Bank C was wealth management not credit cards.

We did not categorize

customers in the merging process. If customers did not use our credit cards, we would send them promotion

material.

If customers did not reply to the notice letters, we did not help them change to new credit cards. The credit card

bonus program of

Bank B was

different from Bank B1. After the merger, customers would choose their favorite credit card bonus program.

The credit card quantities of the two banks were low, and so we did not particularly categorize

customers. After the merger,

we did not close any products or functions of Bank D1. We provided

more diversified

products for our customers.

After the merger, we

did not try

particularly hard to maintain customers of Bank E1. We

notified customers

that their rights would be changed in the merging process. Customers needed to change to Bank E1 credit cards.

We provided new products and service for customers to increase the usage of Bank E credit cards. Our superiors were

not familiar with the credit card business, and so we did not spend too many resources on it. por at e Ma nage m e nt R ev ie w V ol . 3 6 N o. 2 , 20 16 81

Table 5 Service culture Bank D merger

with Bank D1

Bank E merger with Bank E1

Bank A merger with Bank A1

Bank B merger with Bank B1 Bank C merger with Bank C1

Both Banks D and D1 used measures

of state-operated

enterprise performance evaluation, and so there was little difference between them.

Due to changed workload after the merger, some employees felt they had been treated unfairly. After the merger,

we held informal activities to enhance

employees’ interaction.

On the eve of the merger, Bank E1 had a large employee promotion. Bank E felt this was unfair. After the merger, there were

only five employees in the credit card department who moved from Bank E1 to Bank E. Thus, we did not have culture clash problems. We had different

performance evaluation methods between Bank E1 and Bank E. All employees followed the performance evaluation of Bank E after the merger.

After the merger, some employees of Bank E1 were not familiar with the new operation and needed to work harder than before the merger to understand it.

We only bought the credit card business from Bank A1 and did not encounter any culture problems.

We had different

services between

Bank A and Bank A1. After the merger, we sent an SMS or phone call

to remind customers when they used credit

cards for large

consumption. After the merger,

the format of the credit card bill is now different, and so customers have to get used to this.

We had a different organizational structure and task distribution between Bank B and Bank B1. After the merger, we suffered a culture clash.

After the merger, Bank B1

employees were assigned to different departments and felt like “rootless orchids.” Some employees could not adapt to the new environment and left Bank B. Bank B emphasized employee

performance more than Bank B1. The superiors of Bank B recruited employees of Bank B1 whom they wanted to retain.

The employee performance

evaluation system of Bank B evaluated individual performances. Each employee needed to take care

of customers. However, the

employee performance evaluation system of Bank B1 evaluated the department.

We had serious employee performance evaluations. If the employees wanted to continue working in the merged company, they had to provide good customer service.

The culture of Bank C1 is not clear, and so we did not have culture clash problems. Employees adapted to Bank C’s culture and value. If employees in Bank C1 could not adapt to Bank C’s culture, they left the company. We had different management

styles between Bank C and Bank C1. Employees of Bank C1 did not adapt to these

changes. For example,

employees used professional titles to call their colleagues at Bank C1, but employees used their English names in Bank C. T h e r eten tio n o f c u st o m e r rela tio n sh ip s af te r m e rge rs and ac qui si tio ns

Table 6 Process integration Bank B merger with Bank B1 Bank D merger

with Bank D1

Bank E merger with Bank E1

Bank C merger with Bank C1

Bank A merger with Bank A1 After the merger, we used Bank B’s

operational process system.

We divided the training program into many stages for our staff. Two months before the merger, the operational directors of Bank B trained the operational employee representatives of Bank B1. The operational employee representatives needed to read operation manuals and take an internal test. We had employee performance evaluations, and so everyone had different training programs. In the first year of the merger, the leaders of

Bank B1 assigned their outstanding employees to learn the new operational process method of Bank B and then to teach the method to other Bank 1 employees.

After the merger, customers noticed the service process changes. Before the merger, customers went to the bank and hoped employees would help them solve problems. Post-merger, customers now need to call the customer service center, and customer service representatives now deal with customer problems first. After the merger, we followed Bank D’s operational processes although we still maintain some products of Bank D1. Bank D1 did

not have SOP and so we simply follow the operation processes of Bank D. Before the merger, Bank D spent 18 months training Bank D1 employees. At first, Bank E and Bank E1 exchanged employees to learn each other’s operation process. Employees practiced the processes on a daily basis.

Before the merger, we spent four months training employees.

Bank C had global standards, and so Bank C1 needed change its processes to synchronize.

Six months before the merger, the operational manager of Bank C trained employees of Bank C1 on new operation methods. Bank C and Bank

C1 set up a merger team to check the assets.

Bank C had an SOP for each operation that everyone needed to follow.

After the merger, we had Bank A1’s customer lists. Our first task was to analyze the customer condition. After the merger,

we adapted Bank A’s service processes.

After the merger, bank leaders emphasized the customer service training of employees. Front-end employees had three training sessions every day.

por at e Ma nage m e nt R ev ie w V ol . 3 6 N o. 2 , 20 16 83

Table 7 Technology integration Bank B merger with Bank B1 Bank D merger with

Bank D1

Bank E merger

with Bank E1

Bank A merger

with Bank A1

Bank C merger with Bank C1

Bank B IT operation staff were in Taiwan while the design staff and servers were located in Singapore. Thus, computer systems in Taiwan had to connect to the servers in Singapore. The IT employees in Taiwan discussed changes with Singapore employees.

We spent one year on data transfer. We now use Bank B’s systems and closed Bank B1’s systems.

Bank B and Bank B1 spent a lot of time testing the integrated system.

Six months after the merger, the systems of Bank B and Bank B1 operate together. When the system became stable, we shut down Bank 1 systems.

The computer systems of Bank D were different from those of Bank D1. Thus, we needed to update all of those in the Bank D and integrate them with Bank D1.

Before the merger, we set up the IT merger team to discuss information systems problems. We had three formal information system testing sessions.

After the merger, we used Bank D’s system. Employees in Bank D1 needed to be familiar with Bank D’s system.

Before the merger, IT employees of Bank E and Bank E1 spent four months discussing the integration of the two systems. After the merger,

we used Bank E’s systems and provided SOP to our employees. After the merger,

we received many customer complaints. Before the merger, we had many integration meetings. We spent three months performing data conversion. Before the merger, Bank A1 provided Bank A with customer reports. Bank A then analyzed customer data. Before the merger, IT employees of both Bank A and

Bank A1 discussed data

format, database, and CRM.

Before the merger, IT employees spent six months discussing the integration. Before the merger, IT

employees of Bank C spent six months training IT employees of Bank C1. Before the merger, we

conducted eight formal system-testing sessions. Before the merger, we had

to change the system documents of Bank C1 to Bank C’s format. Employees would notify customers about some changes in their accounts. After the merger, we

received many customer complaints. T he r eten tio n o f c u st o m e r re lat ions hi ps a fter m e rge rs a nd ac qu is iti ons

Table 8

Customer and employee communication

Bank A merger with Bank A1 Bank B merger

with Bank B1 Bank C merger with Bank C1

Bank D merger with Bank D1

Bank E merger with Bank E1 Bank A bought Bank A1’s

credit card department. Our managers announced this news to employees of Bank A, but leaders of Bank A1 still need to communicate with their employees. Before the merger, employees

of Bank A1 sent a notice letter to customers that Bank A would be taking care of

their business. Customers

need to confirm this notice letter.

If customers did not reply to the notice letter after two or four weeks, we would do three follow-up calls to valuable customers. We encouraged customers of Bank A1 to change their credit cards to Bank A. If customers did not tell us to cancel their original cards, we would automatically issue new credit cards.

We had a project team to provide customer service and telephone sales for customers. Employees described interests and benefits of the credit cards to customers.

Employees of Bank B communicated with employees of Bank B1. We told them their salaries and welfare would increase after the merger. Employees told customers with corporate cards that they would need to change to a new credit card. We also notified customers who had Bank B1 bank cards. If they did not comment, we changed their bank card to the new credit card.

Before the merger, Bank C set up a project team to communicate with employees of C1. This team also provided training programs on operation processes and information systems for employees of C1.

Bank C belonged to a foreign company and Bank C1 was a local company. Due to these different backgrounds, employees of Bank C communicated with employees of Bank C1 before the merger. However, employees of Bank C1 were still opposed to Bank C. For example, many employees of Bank C1 would not use their computers and email. Many clashes occurred and Bank C needed to provide different channels for Bank C1 employees to cope with their confusion. After the merger, we emphasized customer

service and CRM. We categorized customers

and provided different modes of

communication. We visited or called valuable customers and emailed general customers.

Employees of Bank C spent much time communicating with customers of Bank C1

regarding business adjustments and

substitute plans.

Employees of Bank C provided two or three

formal communication sessions with

customers of Bank C1. Customer bank accounts of Bank C1 needed to change to Bank C. Bank D set up a merger team and communicated with employees about work rights and benefits. Employees had few complaints regarding the merging process. Before the merger, we published information on the merger for three to five days. We also sent letters to notify customers. After the merger, customers had few complaints.

Before the merger, the top management of Bank E communicated with middle managers on merger information. The leaders of Bank E

were not focused on credit card business. The customer base of Bank E1 was small, and we did not want to spend resources maintaining Bank E1’s customers. Almost all customers

knew about the merger from letters, newspapers, and an announcement.

Only few overseas

customers did not know. We retained our original

phone number for

customers.

After the merger, we increased to 100 branches and provided

customers with

convenient services.

Employees called

valuable customers to provide better service.

por at e Ma nage m e nt R ev ie w V ol . 3 6 N o. 2 , 20 16 85

Table 9 Organizational inertia Bank A merger with

Bank A1

Bank B merger with Bank B1

Bank C merger with Bank C1

Bank D merger with Bank D1

Bank E merger with Bank E1 Employees of the credit

card department had to switch customers’ credit cards of Bank A1 to Bank A. When the change was successful, an employee bonus would be provided for the performance. The bonus program was

very important to avoid employee complaints.

After the merger, we had a serious performance evaluation. After the merger, employees had one year to become familiar with the new operation methods. Employees felt stressful, and some left the firm. After the merger, we had

an organizational transformation to make sure of management authority.

Employees of Bank C1 were older than those of Bank C. Employees of Bank C had a difficult time training the new operation method to employees of Bank C1.

Employees of Bank C tried to communicate with the employees of Bank C1 about changes in the organization framework.

Both Bank D and Bank D1 are state-operated, and so we had few differences. During the merger,

employees of Bank D and Bank D1 had some friction, but we had a smooth integration after the merger.

After the merger, leaders emphasized

organizational

effectiveness, efficiency, and service quality. After the merger,

employees of Bank E1 could not adapt to the operation process. Employees of Bank E needed to give them time to learn. Employees tried to maintain customer service quality. T h e re te nt ion of c u st o me r re lat ions hi ps a fte r m e rge rs and ac q ui si tions

5. Discussion

This study verifies four critical factors and finds five additional influential factors in managing CRM in the five banking M&As projects.

5.1 Service culture

Service culture refers to the way in which a merged organization develops organizational capabilities to exceed customer expectations and create value to attract and retain post-merger customers. Since Bank D and Bank D1 and Bank E and Bank E1 were state-operated banks and often deal with state-run companies, their service culture was similar; therefore, Bank D and Bank D1 and Bank E and Bank E1 did not have a culture clash. Bank B and Bank B1 and Bank C and Bank C1 had a distinctive service culture. Due to a different organizational structure and service model, there is a strong culture clash after the merger, which causes customers to experience inconsistent service and disorderly conditions. For example, a representative of Bank B1 described. After the merger, employees of Bank B1 were assigned to different departments and felt like ‘rootless orchids’.” Some employees might not adapt to the new environment and leave Bank B. A representative of Bank C1 mentioned that. We had a different management style between Bank C and Bank C1. Employees of Bank C1 did not adapt to these changes.”

Managers of Bank A and Bank C assessed their customer bases during the merging process and provided promotions for valuable customers to maintain customer relationships. Bank A had great brand identity and customer information. For example, a representative of Bank A said. We held a credit card consumption campaign to analyze potential customers and a representative of Bank C mentioned that. We categorized rich or high-asset customers according to their region and notified nearby branches to be active in providing our fortune management services.” Since Bank E’s merger with Bank E1 was due to policy-driven consideration, they were not focused on customer relationships and customer base assessments.

Bank B and Bank C are foreign companies and thus had different leadership styles and cultures than the local companies. Employees of their target

companies had to learn these changes. Bank B had a transparent checking system and a conscientious standard operating procedure. Both Bank D and Bank D1 are state-operated. A representative of Bank D mentioned that. Employees were protected by government law. After the merger, we received the same benefits and welfare, and so we had little differences.”

5.2 Process integration

Process integration refers to the merged firm dealing with business policy discussions, dataflow synchronization, and procedure standardization for providing customers with consistent service. The merged company provides employees with continuous training for promoting service quality. Training programs help employees learn to reduce customer inconvenience and confusion. Through case studies, we found that the process integration depends on the acquiring company rather than the target company. In addition, the acquiring company provides training programs for the target companies. Bank D and E had fewer customers, and therefore Bank E only took four months to train employees and had fewer problems that occurred in the merging process. For example, a representative of Bank E reported that. Bank E and Bank E1 exchanged employees to familiarize themselves with the operation process. Employees would practice with the processes.” An exception was Bank A, which only bought Bank A1’s credit card business. As a result, Bank A did not exchange employees with Bank A1. Bank B emphasized the protection of customer information and had a powerful call center service.

5.3 Technology integration

As each company has different IT infrastructure and systems, technology integration can provide customers with correct information quickly. Before the merger, the IT employees of two banks discussed information systems, data format, database, and CRM. The two banks also needed to spend time testing the integrated system and participating in training programs. Some small banks could adapt to a larger bank’s information systems. For example, since Bank E1 was a small bank, a representative of Bank E said. Before the merger, IT employees of Bank E and Bank E1 spent four months to discuss the integration of the two systems. After the merger, we used Bank E’s systems and provided

Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) to employees.” In the system transfer process, all of Bank C1’s document formats had to be changed to Bank C’s formats. Many customers of Bank C1 were not satisfied with the change and would not accept only getting Bank C’s statement of account. A representative of Bank C said. Before the merger, IT employees spent six months discussing the integration. IT employees of Bank C spent six months training IT employees of Bank C1 by conducting eight formal system-testing sessions. ”

5.4 Communication with customers and employees

Communication with employees and customers helps firms confirm future strategies and operations during the merging process. Communication might reduce uncertainty and smooth out transitions during changes. All cases followed the merger rules of the Taiwan Financial Supervisory Commission. A representative of Bank C said. After the merger, we emphasized customer service and CRM. We categorized customers and provided different commutation modes. For valuable customers, we visited or called them. For general customers, we emailed or mailed them.” Top management needed to communicate with employees. For example, a representative of Bank D said that. Bank D set up the merger team and communicated with employees about work rights and benefits. Therefore, employees had few complaints in the merging process.” Moreover, employees needed to communicate with customers to remain as valuable customers.

5.5 Additional influential factors

Except for the six critical factors for CRM in banking M&A projects, this study also found influential factors (standard operating procedure of the business transition, customer care, strategic purposes, customer base, brand effect, and organizational mindsets) to affect CRM during the M&As process.

5.5.1 Standard operating procedures of the business transition

Before the merger, firms need to build execution plans and announce them to all employees. This can help the merger process go quickly and smoothly. In particular, understanding how to maintain customer relationships during the M&A process helps to avoid a loss of customers. Bank A, Bank B, and Bank C

had institutionalization rules to provide better services to customers. However, Bank D and Bank E were flexible in service offerings, and employees of the target company just had to learn their operation method. As a result, employees did not quickly learn the new operation method during the chaotic M&As process. Additionally, employees failed to provide better customer service.

5.5.2 Customer care

After the merger, customer follow-up helps firms to understand customer demand and provide better service. If companies do not follow up, their customers might feel as though they are not being respected and may not interact with the company. Therefore, follow-ups with customers may increase customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. The representative of Bank A said “We would do three follow-up up calls to valuable customers. We encouraged customers of Bank A1 to change their credit card to Bank A.” The representative of Bank C also said. Because every communication channel had different costs, we picked out the more valuable customers to use a phone call or dispatched employees to visit them, and we sent emails to connect with the customers whom we thought were less valuable.” Therefore, we found the two banks conducted customer segmentation. Employees provided different promotions and services to different customer segments. Employees visited valuable customers, sent notice letters or made phone calls to provide customized service to encourage the use of credit cards. The call center of Bank B made follow-up calls for all customers. Bank D and Bank E did not follow up on their customers, as the credit card business was not their main business. These banks only posted newspaper notices and mailed letters to maintain their customers. A representative of Bank E said. We did not make follow-up calls for customers of Bank E1 and simply provided the call center phone numbers.”

5.5.3 Strategic purposes

Different types and objectives of bank mergers might affect customer relationships. For example, although Bank C merged with Bank C1 to expand branches in Taiwan, customers of Bank C1 were not Bank C’s target customers, and Bank C did not want to maintain customer relationships of Bank C1. Because Bank D and Bank E merged for policy reasons, such as solving banking

problems and inferior operations, the two banks had to quickly integrate to avoid social problems. As this merger purpose was not to maximize profits, employees only wanted to follow the rules and let the merger proceed smoothly. Employees emphasized maintaining customer relationships. Bank A and Bank B merged to expand their combined credit card market share in Taiwan, and so they actively maintained customer relationships.

The support of top management affects customer services and customer relationships. For instance, Bank E superiors were not familiar with the credit card business, and so they did not spent too much time on it. Bank C’s main business was wealth management, and so superiors did not spend many resources on credit card customer services. Bank D superiors considered that their credit card business had a low market share and profit, and so they did not spend time maintaining customer relationships. The credit card business had not been promoted for a long time and no special bank team existed to maintain customer relationships. The superiors of Bank A and Bank B considered the credit card business important, and so they spent resources to maintain customer relationships. After Bank A merged with Bank B, a synergistic effect developed between the credit card business and customer relations.

5.5.4 Customer base

Customer base influences the merger company to maintain customer relationships. If a target company’s customer base were too small, the merger company would not spend resources to maintain relationships. For instance, the representative from Bank E said that. The customer base of Bank E1 was small and the customer type was also similar to Bank E. Our major business was not the credit card business, and so we decided not to waste resources to maintain these customers.” If a target company customer base were too small, the target company would adopt the products and services of the acquiring company. If customers were not satisfied with their products and services, the company apologized. Therefore, the company did not change their operation methods and did not care if a customer stayed with the bank.

Banks B and Bank C are global companies and have a strong brand effect in the credit card market, a wide range of products, and many branches in other countries. Bank A also had a strong brand effect for consumer financing in

Taiwan. Therefore, the overwhelming majority of customers hoped to switch their credit cards to the acquiring company during the M&As process. Bank D and Bank E are state-operated banks and many customers switched their accounts to the merged bank, not worrying about the banks going bankrupt. Therefore, we found that banks’ brand effect had a huge impact on customers. For instance, the representative of Bank A said that. brand is a major factor for people to recognize. while the representative of Bank C said that. every customer had high expectations for the brand effect of Bank C at the beginning of the merger.”

5.5.5 Organizational mindsets

Organizational mindset refers to company decisions that change the services and increase customer satisfaction. Employees’ mindset refers to employees’ decision to provide better quality services to customers based on received benefits and bonuses. For example, Bank B provided account statements in global branches. After it merged with Bank B1, Bank B decided to keep deposit books for their customers in a local branch to satisfy customer needs. Bank D retained Bank D1’s valuable business to satisfy customer needs during the merging process. Superiors at Bank D1 were responsible for this business and decreased customers’ complaints. Bank C only provided account statements, but no deposit books for customers after the merger with Bank C1. After the merger, many customers complained that Bank C did not consider customer needs. Bank C would not change their globalized operation process or spend resources to provide deposit books. Banks D and Bank E are state-operated banks. Employees did not worry about their benefits and did not want to provide better quality services to customers. After the merger, employees’ performance evaluation, benefits, and bonus did not change. On the other hand, Bank B and Bank C used a personal performances evaluation system, and thus their employees only cared about service quality since better service quality would affect their bonus and benefits. Bank A and Bank B similarly had performance evaluation systems. If employees provided low quality service to customers, then employees would receive a bad performance rating and lower benefits.

6. Conclusion

Previous research has focused on how human resources, culture, technology integration, and financial statements affect M&A performance. Although researchers have used survey methods to evaluate customer satisfaction before and after mergers, it was not deeply understood how companies manage resources before and after M&As. We applied a resource-based view to verify the kinds of intangible customer relationship resources that are needed to hold together after a merger and how companies manage combined resources.

This study posed two research questions: (1) Do enterprises retain the same quality of CRM after M&A?; and (2) How do organizations retain the quality of CRM after M&A? In order to answer the first question, we collected data from eight banks that experienced M&As in Taiwan over the past eight years to compare CRM performance in the credit card business. Moreover, based on the literature review, this study identified six critical factors including strategy for rebuilding the customer base and service portfolio, the service culture, process integration, technology integration, communications, and organizational inertia in managing CRM in M&As projects. To answer the second question, we conducted five in-depth case studies to understand the important factors about managing CRM after M&As. This study found critical factors (service culture, process integration, technology integration, communication with customers and employees) and influential factors (standard operating procedures of the business transition, customer care, strategic purpose, customer base, organizational mindsets) that affected managing CRM after M&As projects. These results could help organizations in developing effective plans for building synergy in CRM after M&As. Future studies may examine or compare the quality of CRM before and after M&As in other industries (Chen, Chu, and Huang, 2012; Chi, 2013). Moreover, future works can apply other methodologies to understand how companies retain the quality of customer relationships after M&As (Lin and Chung, 2011; Shyu, 2014; Yang, Wang, and Ruan, 2013).

Appendix 1

The selected casesMerger The Merged Current Bank Date of M&As Standard Chartered Bank

(180,745) Hsinchu International Bank (397,593) Standard Chartered Bank June 2007 Taiwan Cooperative Bank

(745,178)

Farmers Bank (46,266) Taiwan Cooperative Bank

May 2006 Taishin International

Bank (2,329,547)

Chinfon Bank (647,090) Taishin International Bank

March 2010 Citibank (1,617,971) Bank of Overseas

Chinese (781,427)

Citibank (Taiwan) December 2007 Taipei Fubon Bank

(2,376,638)

International Bank of Taipei (1,509)

Taipei Fubon Bank January 2005 HSBC (586,373) The Chinese Bank

(551,032)

HSBC March 2008

Bank of Taiwan (275,866) Central Trust of China (18,444)

Bank of Taiwan July 2007 Far Eastern International

Bank (1,043,276)

AIG Credit Card Co. (225,715)

Far Eastern International Bank

September 2009

Note: The number means the effective cards before one month of the M&A.

Appendix 2

Descriptions of cases studied and data collection Bank People

Interviewed Interviewees

Total Interview Time Bank A 5 Manager of Customer Management

Department

6 h, 40 min Bank B 6 Manager of Credit Card Department

Manager of Bank B branch 8 h, 50 min Bank C 6 Director of Personal Finance

Department Business managers

8 h, 30 min

Bank D 5 Specialist of Marcom Department

Business managers 8 h, 50 min Bank E 6 Assistant Manager of Bank E branch

Appendix 3

Credit cards issued after merger Standard Chartered Bank merger with

Hsinchu International Bank

Taiwan Cooperative Bank merger with Farmers Bank

Taishin International Bank merger with Chinfon Bank

Citibank merger with Bank of Overseas Chinese

Taipei Fubon Bank merger with International Bank of Taipei

HSBC merger with The Chinese Bank

Bank of Taiwan merger with Central Trust of China

Far Eastern International Bank merger with AIG Credit Card Co.

Appendix 4

Market share after merger Standard Chartered Bank merger withHsinchu International Bank

Taiwan Cooperative Bank merger with Farmers Bank

Taishin International Bank merger with Chinfon Bank

Citibank merger with Bank of Overseas Chinese

Taipei Fubon Bank merger with International Bank of Taipei

HSBC merger with The Chinese Bank

Bank of Taiwan merger with Central Trust of China

Far Eastern International Bank merger with AIG Credit Card Co.