民93年7月 頁117-141

Service Announcements of AIDS

intervention in Hong Kong, 1987-2001:

A Descriptive Analysis with a Cognitive

Paradigm

Hao-Chieh Chang

*ABSTRACT

This study content analyzed the AIDS intervention PSAs produced by the Hong Kong government and televised between 1987 and 2001. A cognitive paradigm was employed to identify and examine the PSA message features that may facilitate processes (i.e., attention, comprehension, yielding, and retention) leading to attitudinal and behavioral changes. The results showed that the PSAs underutilized structural features that may elicit viewers’ involuntary attention. These PSAs also tended to be high on information load and verbal explicitness, but low on visual explicitness. In addition, they were typically targeted at the general public without offering specific information to help the implementation of the recommended preventative actions. Implications of these findings were discussed.

收到日期:92 年 12 月 4 日,接受日期:93 年 2 月 24 日。

* Hao-Chieh Chang, Ph.D., Assistant Professor School of Journalism and Communication, the Chinese University of Hong Kong Shatin, New Territories Hong Kong.

Keywords: AIDS intervention PSAs, message strategies, information

processing, content analysis

INTRODUCTION

The AIDS epidemic has plagued the global community for over two decades, and still poses growing threats to many parts of the world. The disease has an unprecedented severe impact on human lives that goes beyond the confinement of race and geography. For the first time, no country or group of people is beyond the reach of HIV/AIDS. In fact, an estimated 42 million people worldwide were living with HIV/AIDS as the end of 2002 (National Institute of Health, 2002). When AIDS first emerged in the early to mid-1980s, some governments considered it a political risk to acknowledge the threat of AIDS in their nations due to the sensitive nature of AIDS transmission. To acknowledge HIV/AIDS seemed tantamount to acknowledging moral and societal failure (Johnson & Flora, 1997). However, the threat of AIDS was simply too great to ignore. By early 1987, AIDS prevention campaigns had been launched in countries in every continent (Baggaley, 1988; Wayling, 1988). The global fight against HIV/AIDS thus began.

In 1985, the first case of AIDS was diagnosed in Hong Kong. In the same year, public education activities were initiated by the then Medical and Health Department, through the newly established AIDS Counseling and Health Education Service. A territory-wide media campaign on AIDS was launched by the Government in 1987 (Advisory Council on AIDS, 2001). After years of preventative efforts, the prevalence of HIV/AIDS infection in Hong Kong is much lower in comparison with many countries in South and Southeast Asia. According to the latest statistics, the total reported cases of HIV/AIDS in Hong Kong were 2,116 (Department of Health, 2003). In a territory with a population size of 6.7 million (Information Services Department, 2002), such an infection rate (0.03%) is indeed quite disarming. However, AIDS prevention educators and experts have recently warned the public against such misleading optimism for two reasons. Firstly, the symptoms of an AIDS infected patient may take as long as ten years to emerge. Since the current screening process is on a voluntary basis, many infected individuals may not realize their condition. Secondly, the increasing cross-border activities with Mainland China may pose greater

challenges to AIDS prevention in Hong Kong. China, according to a report released at the Sixth International Congress on AIDS in Asia and the Pacific, was in a transitional phase and may be on the brink of potentially explosive epidemics (Agence France-Presse, 2001). More alarmingly, a recent survey commissioned by the Advisory Council on AIDS showed that almost half the Hong Kong men who had sex with prostitutes without any protection believed they were not at risk of contracting AIDS. A misconception that sex workers on the mainland were healthier or disease-free was also found among the men surveyed (Moy, 2001). These misconceptions pose serious questions on the message effectiveness of the AIDS prevention campaigns in Hong Kong. Since TV has been consistently cited as the major source of information about AIDS (Advisory Council on AIDS, 2001; Hong Kong AIDS Foundation, 1993), and PSAs are the core communication product specifically designed for the purpose of promoting health information (DeJong, Wolf, & Austin, 2001), it is worthwhile to examine the informative elements contained in the PSA message to assess the extent to which such informative elements are strategically employed/manipulated to facilitate message recipients’ information processing based on the principles of effective message construction (Johnson & Flora, 1997). Therefore, this study examines the 29 televised AIDS intervention public service announcements (PSAs) produced by the Hong Kong government from 1987 to 2001. Although similar studies have been done (DeJong, Wolf, & Austin, 2001; Freimuth, Hammond, Edgar, & Monahan, 1990; Jones, Johnson & Flora, 1997; 1993; Lee & Choi, 1997; Swanson, 1993a; 1993b), this study explores the PSA characteristics using a systematic and more comprehensive cognitive paradigm. Specifically, this study uses such a cognitive paradigm to identify informative features employed in the messages and to assess how much they are devised according to the theoretical principles of effective message construction. There are two objectives for this research effort: 1) to examine the message elements of the government-produced AIDS intervention PSAs in Hong Kong, and 2) to generate constructive recommendations for future health communication message design based on the implications of the findings.

LITERATURE REVIEW

PSAs are frequently used as the centerpiece of health communication campaigns. They are objects of research interest to many communication scholars and researchers due to their primary and visible role in the public education efforts. Studies on AIDS PSAs from a communication perspective primarily focus on the messages contained in the ads. They generally fall into two lines of research: 1) examining the potential social and/or

cultural implications of the messages to the audiences, and 2) assessing the effectiveness of message features in reaching the audiences.

The first line of research typically analyzed the frames or discourses employed to portray AIDS and its related characters in the PSAs. Using rhetorical, textual, frame, semiotic or other qualitative analysis approaches, these studies (e.g., Hu, 1996; Jones, 1995; Swanson, 1993a, 1993b; Tulloch & Lupton, 1997) tended to adopt a critical perspective in reading the campaign messages produced by various countries and regions. The findings of these studies generally evidenced a conservative intervention climate that encouraged cultural stereotypes reinforcement and used inexplicit terminology and employed fear appeals to attribute blame on the victims (Hu, 1996; Jones, 1995; Swanson, 1993a, 1993b). Some of these studies also argued that government-produced anti-AIDS PSAs tended to support traditional family and social relationships and deny homosexuals and other disenfranchised groups a voice in the fight against the disease (Jones, 1995; Swanson, 1993a, 1993b; Tulloch & Lupton, 1997).

Brinson and Brown (1997) evaluated the persuasive appeals of the PSAs featured in the 1994 “America Responds to AIDS” campaign. They, using narrative analysis, assessed the levels of narrative probability and fidelity in each PSA. They argued when a PSA was presented in a story fashion, it would appeal to larger audiences. Messages with good values communicated would receive greater acceptance. In this sense, the 1994 campaign messages should be effective. However, the PSAs’ failure to address competing narratives adequately constituted the major weakness of the persuasive appeals.

The second line of research in this area tended to employ objective evaluation of the PSA messages. DeJong, Wolf, and Austin (2001) content analyzed 56 U.S. federally funded television AIDS PSAs since 1987. They conducted a descriptive analysis on these PSAs in terms of intended audiences, information exchange, awareness and knowledge, outcome expectations, behavior change skills, self-efficacy emphasis, and communication strategy. The findings indicated that the federal government efforts have failed to meet the needs of high-risk target groups, to promote HIV testing, to offer motivational prevention messages for condom use, and to incorporate basic behavior change theory in the PSA messages.

The findings of other studies (Baggaley, 1988; Calvert, Cocking, & Smrcek, 1991; Flora & Maibach, 1990; Fremuth, Hammond, Edgar, & Monahan, 1990; Huang & Hsu, 1996) in general echoed the concerns of the DeJong et al. study (2001): failure to personalize risk, to incorporate motivational content, to target specific audience, and to provide relevant knowledge and skills for preventative behaviors posed direct threats to the

effectiveness of AIDS campaign messages. All these studies evaluated AIDS PSAs’ messages objectively and provide valuable suggestions to improve the message designs. However, all these studies (Baggaley, 1988; Brinson & Brown, 1997; Calvert, Cocking, & Smrcek, 1991; Flora & Maibach, 1990; Freimuth, Hammond, Edgar, and Monahan, 1990) used selective foci to guide their analyses and evaluations. What was lacking was a more comprehensive criterion to examine the message features based on how an individual processes persuasive information. A study by Johnson and Flora (1997) partially fulfilled the above expectation, and this study attempts to fill the gap left by their study.

Using 317 PSAs from 33 countries produced from 1987 to 1993, Johnson and Flora (1997) examined the degree to which the PSAs incorporated theoretical principles of effective message construction derived from cognitively oriented research. According to these theories, attitudinal and behavioral changes follow an ascending ladder of audience attention, comprehension, yielding, and retention (McQuire, 1989; Petty & Cacioppo, 1981). Johnson and Flora (1997) chose to focus on the three latter rungs (comprehension, yielding, and retention) and ignored the first one (attention) completely without any justification. In fact, attention can be a critical step in processing persuasive information— an entry point that decides whether a message will be attended to at all (Chafee & Roser,1986; Lang, 1990). A message needs to attract an individual’s attention before it can be further processed (Anderson, 1995). Since most AIDS PSAs are targeted at the general public, the majority of the audiences are more likely to be lowly involved with the messages (Freimuth, Hammond, Edgar, & Monahan, 1990; Johnson & Flora, 1997; Solomon, 1989). The persuasion, if occurs at all, is more likely to take the peripheral route (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). In this sense, the PSA messages containing structural features that are able to elicit orienting responses from the audiences may have a greater chance to “catch” their attention (see Lang, 1990 for a brief review on “involuntary attention”), and thus have a greater chance of being further processed via the peripheral route. One may generate an incomplete picture, when assessing the informative elements devised in the AIDS PSAs, if one overlooks the attention factor. This study, therefore, uses a more comprehensive cognitive paradigm, containing attention, comprehension, yielding and retention, to examine the message features embedded in the AIDS intervention PSAs in Hong Kong.

METHOD

Collection of PSAs

December 2001 was acquired via two venues. First, a local office of Red Ribbon Center— an AIDS intervention center collaborating with the UNAIDS program was contacted. The Center provided a VCD that contained 27 AIDS intervention PSAs in both Chinese and English versions produced between 1987 and 1998. Since the Chinese version is the primary version and the majority (94.9%) of Hong Kong residents are Chinese (So, 2001), only the Chinese version was analyzed. Secondly, two more PSAs in the Chinese version produced after 1998 were obtained from the Virtual AIDS Office of Hong Kong— a government website dedicated to AIDS prevention. These 29 PSAs made up the population of government-produced television announcements on AIDS awareness and prevention (see Appendix 1 for brief descriptions and intervention foci of these PSAs).

Description of Variables Used in the Analysis

The analysis is based on a cognitive paradigm that consists of four critical processes, including attention, comprehension, yielding, and retention, related to attitudinal and behavioral changes. Message features that facilitate each process are identified and examined. The description of these message features is as follows:

Attention. Previous studies (Anderson, 1985; Lang, 1990; Reeves et al., 1986) show that structural features, such as cuts, zooms, and edits, of television commercials increase viewers’ attention level. These structural features are particularly useful in attracting involuntary attention from people with little involvement with content of the message (Lang, 1990; Lang & Geiger, 1993). In addition, use of informative objects (i.e., salient objects that stand out of the context, such as an octopus on the head of a fashion model) has been found to elicit viewers’ orienting responses and thus increase their attention level (Loftus, 1976; Chew & Sethuraman, 2000). Incorporating informative objects, such as an animated moving condom or a guardian angel on one’s shoulder, in a PSA may enhance the message’s chance to catch viewers’ eyes. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, number of cuts and whether an informative object was used in each PSA are examined to assess whether the messages are designed with an intention to attract attention.

Comprehension. The quality and quantity of information play a critical role in the process of comprehension (Anderson, 1995; Keller & Staelin, 1987). People are likely to be persuaded by messages they can easily attend to and comprehend (Gardner, 1966). Whether a viewer can understand a PSA message frequently depends on how explicit the message is (Bransford & McCarrell, 1974). Vague or inexplicit statements are usually at risk of generating confusion. This study rates the verbal and visual explicitness of the PSA messages, which is based on the coding scheme developed by Johnson and Flora (1997). Verbal explicitness is defined as how bluntly the PSA referred to sex and needle-sharing,

the major routes of AIDS transmission cited in literature (Johnson & Flora, 1997). The degree of bluntness in presenting these two major transmission routes may have a critical influence on viewers’ basic knowledge acquisition about AIDS. Therefore, a PSA is considered to be highly explicit if it referred to these activities directly. If euphemisms such as “stay faithful” or “stay clean” were used, it is rated as moderately explicit. A PSA was low on explicitness if no hint was made. As for visual explicitness, similar to the criteria used for its verbal counterpart, it is rated as high, moderate, or low respectively based on whether these activities were clearly shown, with implied gestures or simply talked about without any visual element (Johnson & Flora, 1997).

This analysis also examines the quantity of the information provided. Too much information is likely to result in a cognitive overload, while too little information creates confusion (Anderson, 1995; Keller & Staelin, 1987). The total number of statements contained in each PSA is counted. They are further sorted in terms of information type (i.e., information or recommendations) and subject category (e.g., practicing safer sex, avoiding needle sharing, etc.). A PSA containing three or more categories of information are considered as high on information load, two categories as moderate and one as low (Johnson & Flora, 1997).

Yielding. The likelihood that a viewer will yield to the PSA’s recommendations depends primarily on how he/she perceives the source and the feasibility of recommendations (Johnson & Flora, 1997). In terms of the source, source credibility and source proximity are two criteria used to assess the source element in the PSA messages. Characters who are perceived as high on credibility (e.g., celebrities or professional experts) are more persuasive (McCracken, 1989; McQuire, 1989). On the other hand, the characters that viewers can identify with are more easily to produce a modeling effect (Atkin, 2001; Bandura, 1977; 1986). Whether the modeling effect will be activated via the process of identification also depends on the type of target audiences. Therefore, type and gender of the source and the target audience(s) are both explored in this study.

As for feasibility of recommendations, it is important that a PSA provides viewers with relevant knowledge and/or skills to negotiate/practice the actions recommended (Freimuth, Hammond, Edgar, & Monahan, 1990). This study therefore examines whether such knowledge and/or skills were provided in each PSA.

Retention. Previous studies (e.g., Freimuth, Hammod, Edgar, & Monahan, 1990; Johnson & Flora, 1997; Solomon, 1989) found that most of the government-produced AIDS PSAs were targeted at the general public, and the majority of the audiences were likely to be lowly involved with the messages. Flora and Maibach (1990) found that

viewers with low issue involvement tend to remember emotional appeals better. Consequentially, message appeals delivered through different types of presentation format (e.g., factual vs. story) may have an impact on viewers’ memory. Therefore, the PSAs are categorized as using rational appeals (delivering facts), emotional appeals (dramatizations), or both.

Coding Procedures

Based on the cognitive paradigm, a coding scheme containing examinations on various variables was developed. These variables included number of cuts, use of informative objects, information explicitness, information load, information categories, sources, target audience, feasibility of recommendations, and type of appeals. The content of PSAs was transcribed to facilitate the coding process. Two coders were asked to view and code the PSAs separately, with one analyzing 15 PSAs and the other 14 PSAs. Over 20% (i.e., six) of the PSAs were randomly selected and coded by both coders to establish the intercoder reliability. Intercoder agreement ratio developed by Holsti (1969) was used to assess each item, with the ratio ranging from 74% to 100% and averaging 95%.

RESULTS

The 29 AIDS intervention PSAs under examination were produced by the Hong Kong government between 1987 and 2001. These PSAs, as core communication product of the AIDS intervention campaign in Hong Kong, manifested the evolution of message strategies employed across these fourteen years. The fourteen-year span can be divided into four stages based on the message strategies employed. At the first stage (1987-1990), fear appeals were widely utilized. From the campaign slogans to the gloomy images and depressing sound/music effects, all the message cues seemed to cultivate an “everyone-is-at-risk” climate and promoting a “breaking-no-rules-or-else” ideology. Contracting the disease was depicted as a personal moral failure associated with prostitution, causal sex or drug use. At the second stage (1991-1994), positive appeals were employed in almost all the PSAs produced during this period. Campaign endeavors that stressed on clarifying misconceptions about and promoting public discussion of the disease were presented in story formats. The messages presented typically appealed to individual rationality and responsibility in fighting the disease.

The message strategy used in the third stage (1995-1998) was basically an extension of the second stage. Local celebrities were employed to deliver rational appeals on various issues related to AIDS in a talking-head format. The PSAs produced in 2000 and 2001

marked a new stage for AIDS intervention campaign in Hong Kong as a new monitoring mechanism had been activated by taking annual territory-wide surveys on AIDS-related sexual behavior in 1999 (Advisory Council on AIDS, 1999). The PSAs were designed to target at the heterosexual male having commercial sex as the annual surveys consistently found that this risk group was less likely to practice safer sex (Moy, 2001). Emotional appeals presented in story formats were typically employed. The message elements contained in the 29 PSAs across the four stages in these fourteen years were further

examined with a cognitive paradigm and the results are as follows:

Attention

Number of cuts. Cuts are considered a structural feature that is able to elicit orienting responses from the viewers. The orienting response is an involuntary, automatic response elicited by changes in the environment (Lang, 1990). It is argued that a PSA containing more cutsis more likely to capture and sustain viewers’ attention. Without doubt, the number of cuts within a PSA should be within an individual’s processing capacity. A typical 30-second PSA should not contain more than 30 cuts to avoid disorienting viewers. The 29 PSAs under examination contained cuts ranging from three to 21, with 22 PSAs having 15 or fewer cuts.

Use of informative objects. Informative objects are defined as objects that are in some sense incompatible with the context they are in, thus they stand out to capture people’s attention. Out of the 29 PSAs, only five were found containing informative objects. They include a turning pyramid (an icon used in the early stage of the campaign, see Exhibit I), a purple electric wave circling the pyramid, an animated moving condom, a pinkish yoke turning red, and a wedding picture superimposed on the doctor’s office door before a wife going in for the results of her AIDS test. However, few of these informative objects were prominently featured or emphasized. For instance, the moving condom appeared only at the last shot of the PSA and was not strategically placed to attract viewers’ attention to the message presented. The attention-grabbing potential of these information objects was thus not fully utilized.

Comprehension

Type of information. The PSA information was divided into ten categories: (a) talking to friends and/or family members about AIDS, (b) AIDS tests, (c) drug use, (d) condom use, (e) the number of sexual partners, (f) commercial sex, (g) sexual encounters between men, (h) anti-discrimination, (i) general information about AIDS, and (j) unrelated information.

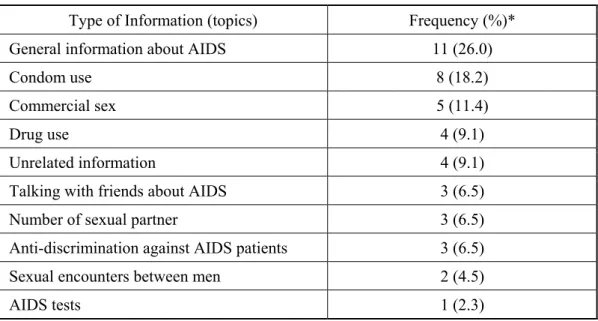

information types coded, the most frequently mentioned topic was general information about AIDS, followed by condom use, commercial sex, drug use, and unrelated information (see Table 1 for specific frequencies and percentages). Three topics, talking with friends about AIDS, number of sexual partners, and anti-discrimination against AIDS patients, received the same proportion of coverage (6.5%). The topic of sexual encounters between men was only covered twice, making up 4.3% of all the topics discussed. Interestingly, AIDS tests were only mentioned once and very casually in a conversation.

Table I. Frequencies (percentages) of Types of Information Contained in the PSAs Type of Information (topics) Frequency (%)*

General information about AIDS 11 (26.0)

Condom use 8 (18.2)

Commercial sex 5 (11.4)

Drug use 4 (9.1)

Unrelated information 4 (9.1)

Talking with friends about AIDS 3 (6.5)

Number of sexual partner 3 (6.5)

Anti-discrimination against AIDS patients 3 (6.5) Sexual encounters between men 2 (4.5)

AIDS tests 1 (2.3)

*A total of 44 mentions of these topics were contained in the 29 PSAs.

Type of recommendation. Compared with information provided, the Hong Kong government seemed more hesitant about providing recommendations. Four PSAs avoided them entirely. Eight of them provided general advice such as “take precautions,” “talk more about AIDS,” etc. Another eight urged condom use. Abstinence and anti-discrimination were featured in three PSAs each. Other recommendations include avoiding sharing needles (two PSAs), limiting the number of sexual partners (one PSA), and seeking more information (one PSA). Interestingly, most of the PSAs analyzed displayed the phone number of an AIDS hotline without urging viewers to call for consultation and seek more information.

Information load. Twelve out of the 29 PSAs were considered as containing high information load (i.e., containing three or more categories). An example of high information load may be found in the first AIDS PSA produced in Hong Kong. In such a

PSA, information about the disease, risk groups, transmission patterns, and the campaign theme were packed in a 30-second announcement:

AIDS is a deadly disease transmitted via sexual contacts. Not only the homosexual, but ordinary people can contract AIDS, too. Because AIDS virus can remain latent for years, people who have contracted the virus may not know they are carriers. Having sexual contact with a person, meaning that you are having sex with the sexual partners that he/she had in the past seven years. Anyone can be a carrier.

Tag line: AIDS is like a pyramid of death (author’s translation).

Nine and eight of the PSAs analyzed were rated as containing moderate and low information load, respectively. The result of a nominal correlation test shows that PSAs in story format were more likely to be low in information load (Cramer’s V =.49, p<.05). It is probably that PSA in story format tended to develop on a single storyline, which limited the categories of information covered.

Information explicitness. The variable has been divided into two levels: visual explicitness and verbal explicitness. In terms of visual explicitness, only three out of the 29 PSAs were considered containing explicitly visual portrayals of sex or drug use. In the PSA, titled “the use of condom,” a couple was getting undressed, patting and kissing each other. It contained partial nudity, a close-up shot of a condom as a foreplay element, and a love scene in the end. The other two PSAs showed explicit scenes of drug use and needle sharing (see Exhibit II). These three PSAs constituted the rare exceptions of the whole population. Among the rest of the PSAs, eight referred to sex or drug use with vague or implying gestures and the other eighteen provided no visual element at all.

As for verbal explicitness, the government-produced PSAs in Hong Kong were not shy in referring to sex or drug use directly. Words such as sexual contacts/partners, sexual intercourse and condom were frequently mentioned in the PSAs. Eighteen out of the 29 PSAs were considered as high in verbal explicitness. Although quite a sizable portion (i.e., seven) of the PSAs did not mention these terms at all, it does not mean that they avoided these topics. In fact, five of the PSAs that fall into this category focused on other nonsexual/non-drug-using topics such as anti-discrimination or clarifying misconceptions.

Yielding

Sources. Sources refer to the characters who lent their faces, voices or celebrity statuses to deliver the PSA messages (McQuire, 1987). Nineteen of the PSAs analyzed

used unknown, ordinary actors. These actors are considered as proximal sources that target audiences can identify with. Local celebrities were featured in eight of the PSAs. Most of them were actors or radio DJs. Interestingly, no medical professionals (experts) were featured. Only one real AIDS patient was featured in a PSA addressing the discrimination issue.

In terms of gender of sources, 16 of the PSAs featured male sources, while five featured female sources and the remaining eight featured sources of both sexes. However, almost all the PSAs featured a male authoritative-sounding voiceover at the end.

Target audiences. A PSA’s target audience is inferred from 1) gender or demographic characteristics of the primary character, or 2) the type of situation portrayed. Seventeen of the PSAs were considered targeting at the general public. Six were targeted at men specifically; only three were targeted at their female counterparts. The remaining three PSAs were produced to reach high-risk groups such as MSM (men having sex with men), drug users and travelers.

Feasibility of recommendations. The majority of the PSAs provided some kind of recommendations, though some were vague. However, only two out of the 29 PSAs provided the target audiences with relevant knowledge or skills to practice/negotiate the recommended actions. The rest of the PSAs simply asked people to practice the actions properly without telling them how the proper actions should be carried out. For example, one of the PSAs featured a young man in a flight returning from a trip abroad, who was later diagnosed with AIDS. We could infer from his friends’ conversation that he had a sex escapade abroad. The voiceover then advised the viewers to take “precautions” on trips to avoid contracting AIDS. However, no other information was offered to further define the so-called “precautions,” not to mention the relevant knowledge or skills to help carry out the preventative measures.

Retention

Type of appeals. PSAs presented in a dramatic format that utilize emotional appeal are found to enhance viewers’ retention of the message (Brinson & Brown, 1997; Flora & Maibach, 1990). Twelve of the PSAs were delivered in factual format, with no story told and the sources/characters looked into the camera to deliver the facts. Although seventeen of the PSAs examined were in story format, six of them were so loosely structured that the stories did not have a clear beginning or ending. They were more like snapshots of someone’s life.

DISCUSSION

Findings

Using a cognitive paradigm, this study identifies message features that may facilitate processes critical to attitudinal and behavioral changes. In terms of attention, it is found that the PSAs in Hong Kong underutilized structural features such as cuts and informative objectives. The majority of the PSAs examined can be categorized as slow to moderate paced and without surprising focal points to capture viewers’ attention. As argued earlier, many viewers for the AIDS PSAs would be lowly involved with the issue; featuring “eye-catching” elements in the PSAs may be a good strategy to elicit their involuntary attention.

As for facilitating the process of comprehension, there is also room for improvement for these PSAs. Although they were verbally explicit in using specific terminology such as sex and drug use, they were not visually explicit enough. Since TV is considered a visual medium and people tend to learn more visual than verbal information from this medium (Lang, 1990), it is important to enhance the visual explicitness to facilitate viewer comprehension. The majority of these PSAs were also not particularly helpful in providing essential and subject-specific information. A sizable portion of the information and recommendations featured was general information and advice. Such types of information and recommendations may only leave people with information overload, but help little with their understanding of the issue at hand. Ironically, given the weakness in information specificity, hardly any PSAs urged viewers to seek more information.

The leading two sources used in these PSAs were ordinary characters and celebrities. They were contended to be effective in gaining viewer yielding via social proximity and source credibility, respectively (Atkin, 2001; McCracken, 1989). However, some weak arguments employed by some celebrities may undermine the effectiveness of their credibility. For instance, in the PSA promoting condom use between married couples, a local movie star, Do Do Cheng, compared the need to use a condom for men to putting on make-up for women. The argument was so weak; it did not even make sense logically: Women put on make-up to look pretty for their husbands, so their husbands should put on condoms to protect their wives. This was a PSA targeting women, but no negotiation strategies were offered to these viewers. Based on Cheng’s argument, should women threaten to take off their make-up and look ugly if their husbands refuse to use condoms? More seriously, such a message indeed reinforced a sex-role stereotype with females being subject to pleasing their men and longing for their affection. It indicated that the AIDS PSAs were typically confined to a male-gaze perspective, even with a PSA targeting at

female viewers (see Exhibit III).

The use of proximal sources in these PSAs was also problematic. Supposedly, proximal sources can enhance the modeling effect proposed by Bandura (1977, 1986). However, the major characters featured in slightly over half (56%) of the PSAs using proximal sources were seen either engaged in or suffering from the consequences of such negative behaviors as prostitution and/or drug use. Lack of positive role models and failure to emphasize on self-efficacy may weaken the effect of proximal sources. Overemphasis on fear/anxiety may scare the viewers away from contemplating the health risks (Dillard & Plotnick, 1996; Floyd, Prentice-Dunn, & Rogers, 2000).

Similar to many previous studies (Baggaley, 1988; Brison & Bown, 1997; Freimuth, Hammond, Edgar, & Monahan, 1990), this study also found that most of the PSAs failed to provide specific knowledge and/or skills for preventative behaviors. Without the guidance of such knowledge and skills, the feasibility of recommendations may be reduced. Simply telling people to be stay abstinent cannot help them reach that goal (Atkin, 2001). Behavioral guidelines, negotiation strategies and emphasis on self-efficacy need to be offered to facilitate the effect of sources on attitudinal and behavioral changes.

As for the type of appeals used, the majority of Hong Kong AIDS PSAs opted for emotional appeals presented in story format. Although dramatizations are argued to have a stronger impact on viewers’ retention than the factual format (Johnson & Flora, 1997), one needs to bear in mind that not all story formats can achieve the effects we expect. Only when story formats are well structured (i.e., strong narrative probability), have values well communicated (i.e., strong narrative fidelity), and have competing narratives anticipated and negotiated will they have an ensured advantage over factual formats. In this sense, Hong Kong AIDS PSAs still have room for improvement.

Limitations of the Study

This study has a number of limitations: First of all, the reliance on categorization— specific features are identified for each cognitive process. However, these cognitive processes do not work independently. They are more likely to influence each other, with higher attention leading to better comprehension, stronger yielding, and greater retention. Therefore, a disadvantage on a specific process may undermine the subsequent processes. In this sense, the total evaluation on all the message features does not equal to a PSA’s total potential influence on a viewer.

Secondly, limited features identified for each process—there may be other features which are related to the cognitive process specified, but overlooked by this study. Take

attention for an example, other structural features such as music, noise, colors or zooms may also have potential impacts on viewers’ orienting responses. This study chose cuts because their objective nature and their effects have been well documented (Lang, 1990; Lang et. al., 1999; Lang & Geiger, 1993).

Finally, emphasizing message over other factors—this study examines the potential effects of message features, but these effects may be different in the real world setting. For instance, the context in which a PSA is presented may influence the effectiveness of these message features (Belch & Belch, 2001). The cognitive advantage of a fast-paced PSA may get lost in a clutter of fast images when shown between two fast-paced commercials, while a slower-paced one may stand out instead. Since most campaigners have no control over when or where the PSA will be shown, it is difficult to factor in the context variable.

Recommendations

One of the major objectives of this study is to generate constructive recommendations for future health communication message design based on the implication of the findings. This study examines the informative construction of PSAs’ message designs and identified message features that may facilitate one’s information processing, attitudinal and behavioral changes. Future health communication designers may want to incorporate these considerations into the development of message features. A theory-based design will help us anticipate possible problems and have a better estimation of the objectives that a PSA can achieve (McQuire, 1989).

Examining all the PSAs ever produced by the Hong Kong government, one is able to sense that these PSAs were developed at different stages to deal with different emergent problems. The PSAs combating misconceptions were produced because the social climate at that time was hostile to AIDS patients. However, one cannot help noticing that the hostility was in some way fostered by the government’s previous “everyone is a possible AIDS virus carrier, trust no one” campaign messages. In some sense, those PSAs may shape public perceptions of the disease and generate cultural representations of the disease. To make good use of the PSAs, the campaign planning should take the initiative to be proactive rather than reactive. Instead of asking, “What are the gaps in public knowledge and what do we need most urgently to convey?”, campaign planners should ask, “How do we want the public to think about HIV/AIDS?” (Johnson & Flora, 1997). With this question in mind, campaign planners should realize the point to show explicit image with explicit language is not to find out “How much can we show and get away with?”, but to find out a realistic way to present a picture of AIDS. When providing information and recommendations, one should always ask, “How realistic is it to ask a young man to remain

abstinent?” “How realistic is it to ask a woman to demand a man use a condom?” Fighting against AIDS should go beyond catchy slogans and neat tag lines. It should have the practicality to be incorporated into one’s daily life.

REFERENCES

Abernethy, A. M. (1998). Television station acceptance of AIDS prevention PSAs and condom advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, 38, 53-63.

Advisory Council on AIDS (1999, May). Press release: CUHK monitors AIDS-related sexual behavior in Hong Kong [Online]. Available: http://www.info.gov.hk.

Advisory Council on AIDS (2001, February). Position paper: The government’s involvement in promoting public awareness on AIDS in Hong Kong [Online]. Available: http://www.info.gov.hk.

Agence France-Presse (2001, October 5). Asia ‘must act now’ to stop AIDS devastation.

South Morning China Post, 12.

Anderson, J. R. (1985). Online cognitive processing of television. In L. F. Alwitt & A. A. Mitchell (Eds.), Psychological processes and advertising effects: Theory, research,

and application. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Anderson, J. R. (1995). Cognitive psychology and its implications. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Atkin, C. K. (2001). Theory and principles of media health campaigns. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public Communication Campaigns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Baggaley, J. (1988). Perceived effectiveness of international AIDS campaigns. Health

Education Research, 3, 7-17.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Belch, G. E. & Belch, M. A. (2001). Advertising and promotion: An integrated marketing communications perspective. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Bradsford, J., & McCarrell, N. (1974). A sketch of a cognitive approach to comprehension. In W. B. Weimar & D. S. Palmero (Eds.), Cognitive and symbolic processes (pp. 189-229). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Brinson, S. L., & Brown, M. H. (1997). The AIDS risk narrative in the 1994 CDC campaign. Journal of Health Communication, 2, 101-112.

Calvert, S. L., Cocking, R. R., & Smrcek, M. (1991). AIDS public service announcements: A paradigm for behavioral science. Journal of Applied Development

Psychology,12, 255-267.

Chaffee, S. H., & Roser, C. (1986). Involvement and the consistency of knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors. Communication Research, 13, 373-399.

Chew, F., & Sethuraman, J. (2000, August). Conceptualizing and testing the construct “impactiveness:” Analyzing the effect of visual stimuli eliciting eye-fixations, orienting responses and memory-stored images on ad recall. Paper presented at 2000 Annual Conference, Phoenix, AZ.

DeJong, W., Wolf, R. C., & Austin, S. B. (2001). U.S. federally funded television public service announcements (PSAs) to prevent HIV/AIDS: A content analysis. Journal

of Health Communication, 6, 249-263.

Department of Health (2003, August 12). AIDS situation in second quarter of 2003. Press Release [Online]. Available: http://www.info.gov.hk/aids.

Dillard, J. P., & Plotnick, C. A. (1996). The multiple affective outcomes of AIDS PSAs: Fear appeals do more than scare people. Communication Research, 23, 44-72. Flora, J., & Maibach, E. (1990). Cognitive responses to AIDS information: The effects of

issue involvement and message appeal. Communication Research, 77, 759-774. Floyd, D. L., Prentice-Dunn, S., & Rogers, R. W. (2000). A meta-analysis of research on

protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 407-429. Freimuth, V. S., Hammond, S. L., Edgar, T., & Monahan, J. L. (1990). Reaching those at

risk: A content-analytic study of Study of AIDS PSAs. Communication Research,

17, 775-791.

Gardmer, D. M. (1966). The effect of divided attention on attitude change induced by a persuasive marketing communication. In R. M. Haas (Ed.), Science, technology &

marketing (pp. 532-540). Chicago: American Marketing Association.

Hong Kong Advisory Council on AIDS (2001). API on AIDS, Hong Kong, 1987-2001. Task Force on Media and Publicity, Committee on Education and Publicity on AIDS [Online]. Available: http://www.27802211.com.

employed in the AIDS prevention PSAs in Taiwan(健康促進在大衆傳播媒體上 之應用研究—探討國內愛滋病防治公共宣導短片的健康說服策略),1996 全 國傳播學生論文研討會。

Huang, S. C. & Hsu, M. L. 黃淑貞、徐美苓(1996). Content analysis of the 1995 AIDS prevention campaign materials in Taipei, Taiwan.(民國 84 年大臺北地區

愛滋病媒體宣導內容分析研究),《衛生教育雜誌》,第16 期。

Information Services Department (2002). Hong Kong: The facts [Online]. Available: http://www.info.gov.hk.

Johnson, D., & Flora, J. A. (1997). HIV/AIDS public service announcements around the world: A descriptive analysis. Journal of Health Communication, 2, 223-235. Jones, R. H. (1995, April). Talking about AIDS in Hong Kong: Cultural Models in Public

Health Discourse. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Southeast Asian

Ministers of Education Organization Regional Language Center Seminar, Singapore.

Keller, K. L., & Staelin, R. (1987). Effects of quality and quantity of information on decision effectiveness. Journal of Consumer Research, 14, 200-212.

Lang, A. (1990). Involuntary attention and physiological arousal evoked by structural features and emotional content in TV commercials. Communication Research, 17, 275-299.

Lang, A., & Geiger, S. (1993). The effects of related and unrelated cuts on television viewers’ attention, processing capacity, and memory. Communication Research,

20, 4-29.

Lee, S. S., Choi, T. M. Y. (1998, June). Using TV advertising for social marketing of AIDS

prevention messages. Paper presented at the 12th World AIDS Conference.

McCracken, G. (1989). “Who is the celebrity endorser?” Cultural foundations of the endorsement process. Journal of Marketing Research, 2, 141-145.

McQuire, W. J. (1989). Theoretical foundations of campaigns. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (pp.43-65). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. Moy, P. (2001, August 26). AIDS ignorance widespread. South China Morning Post. National Institutes of Health (2002, December). HIV/AIDS Statistics, Fact Sheet by Office

Diseases [Online]. Available: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/aidsstat.htm. Petty, R., & Cacioppo, J. (1981). Attitudes and persuasion: Classic and contemporary

approaches. Dubuque, IA: William C. Brown.

Petty, R., & Cacioppo, J. (1986). Communication and persuasion: Central and peripheral routes to attitude change. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Reeves, B., Thorson, E., Rothschild, M., McDonald, D., Hirsch, J., & Goldstein, R. (1986). Attention to television: Intrastimulus effect of movement and scene change on alpha variation over time. International Journal of Neuroscience, 25, 241-255. So, A. (2001, October 27). Census shows wider wealth gap. South China Morning Post, 1. Solomon, D. S. (1989). A social marketing perspective on communication campaigns. In R.

E. Rice & C. K. Atkin (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (pp. 87-104). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Swanson, D. J. (1993a, April). “Repellent and Shameful”: The Portrayal of AIDS in “American Responds to AIDS” Broadcast Public Service Announcements, 1987-1992. Paper presented at the annual Sooner Communications Conference, Norman, OK.

Swanson, D. J. (1993b, November). Mass Media Message, Myths and Martyrs: Analyzing

“American Responds to AIDS” Public Service Announcements, 1987-1992. Paper

presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, Miami Beach, FL.

Tulloch, J., & Lupton, D. (1997). Television, AIDS and risk: A cultural studies approach to health communication. St. Leonards, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Wayling, S. (1988). The European experience: Public education with regards to AIDS prevention. International Journal of Health Education, 7, 16-20.

Appendix I. AIDS Intervention PSAs Produced by Hong Kong Government, 1987-2001 Title Year

Released Description Slogan

Intervention Focus Pyramid 1987

AIDS spreading among people to form a death pyramid

“AIDS is a pyramid of Death” Condom 1987

Man and woman walking into MTR stations and seeing print AIDS ads.

“Use condom for safer sex”

High Risk Group 1987

Word AIDS moving across screen

“The more sex partners you have, the more chance of being infected”

Prevention(Bar) 1987

Man and woman flirting in a Bar; two men leaving together

“You may be the next victim; you never know who could be an AIDS carrier.” 1987— Providing information on AIDS transmission paths; raising awareness of the disease; using fear appeals to induce an “everybody-is-at-risk” feel

Youth & Prostitution 1988

Two young men going to a prostitute after watching a strip show

“It only takes one sexual encounter to contract AIDS. Why risk it?” Infection of

Ordinary people 1988

Portrayal of

businessman’s encounter with a prostitute

interspersed with scenes of his funeral

“It only takes one sexual encounter to contract AIDS. Why risk it?”

Homosexual 1988

Two men meeting in an outdoor café and leaving together; one man changing his mind after seeing AIDS ad on a bus

“It only takes one sexual encounter to contract AIDS. Why risk it?” Sharing Needle 1989

Portrayal of IV drug users sharing a syringe

“AIDS kills. Never share a needle.” Safer Sex/Condom 1990

A man in a cheap hotel getting ready for bed with a undisclosed partner behind him “AIDS kills. Use a condom” 1988-90— Highlighting specific risk groups and behaviors; using fear appeals to emphasize the close association between AIDS and death; calling attention to AIDS Preventive measures and awareness

Title Year

Released Description Slogan

Intervention Focus

AIDS & Travelers 1990

A man returning from a trip abroad and ending up in a hospital with AIDS

“Take extra precautions to avoid exposure to AIDS when travelling abroad” Misconception (I) 1991 People eating in a restaurant “You can’t catch AIDS from sharing the same meal Misconception (II) 1991

Industrial workers working side by side

“You can’t catch AIDS from using the same tool” Misconception (III) 1991

Birthday party “You can’t catch AIDS by just being close to others” 1991— Clarifying general public’s misconceptions about AIDS transmission paths Stuntman 1992

Movie star Jackie Chan comparing sex to doing dangerous stunts

“AIDS is a killer disease. For safer sex use a condom” The Use of Condoms 1992

Man and woman having sex after a foreplay involving use of condom

“For safer sex, always use a condom” Women Protection 1992

Movie star Do Do Cheng comparing using a condom to putting on make-up

“Do the right thing, always use a condom” 1992— Promoting condom use through celebrity endorsement and erotic visual cues

Husband 1993

A man about to become a father finding out an old girlfriend has AIDS

“Think about AIDS. It could happen to you”

Girl 1993

A girl learning that an old fling has AIDS

“Think about AIDS. It could happen to you”

1993—

Promoting the idea that one has to take the consequences for one’s past behaviors Three Women

(Salon) 1994

Three women in a hair salon talking about having AIDS tests

“The more you know, the less the risk”

1994—

Title Year

Released Description Slogan

Intervention Focus Talk About AIDS

(Mouth) 1994

Close-ups of mouths talking about how people don’t talk about AIDS

“The more you know, the less the risk” about AIDS to enhance public awareness The story of J.J. 1995 An AIDS patient appealing for care and support for AIDS patients

“Don’t discriminate AIDS patients, give them more care”

Appeal by Celebrity:

Pamela Pak 1996

Local celebrity appealing for safer sex

Appeal by Celebrity:

Paul Tse 1996

Local celebrity appealing for treating AIDS patients fairly

Appeal by Celebrity:

Li Pik Sum 1996

Local celebrity appealing for fair treatment for AIDS patients Appeal by Celebrity:

Hung Chiu Fung 1996

Local celebrity appealing for safer sex

Appeal by Celebrity:

Gary Ngan 1996

Local celebrity appealing for AIDS prevention

1995-96— Appealing for fair treatment of AIDS patients; Promoting practice of safer sex and awareness of other preventive measures Be a Responsible

Man Use a Condom 1998

A TV star wondering in a supermarket looking for condoms

“Prevent AIDS, be a responsible man”

Sharing Needle 2000

A woman being diagnosed of AIDS; her husband recalling having sex with a prostitute and using drugs “Don’t share needles, use condoms properly” Metaphor (Egg) 2001

A young man questioning the chance to contract AIDS after having sex with a prostitute. “STD & AIDS prevention starting from men” 1998-2001— Emphasizing on men’s responsibility on preventing AIDS transmission; targeting at the heterosexuals as they had comprised the majority of the infected patients

Exhibit I: A turning pyramid in “Pyramid” 1987

Exhibit II: Visual explicitness in “Sharing Needle” 1989