Hsing-Er Lin

1and Edward F. McDonough III

21

hsinger.lin@gmail.com*

Research associate

Maastricht School of Management Maastricht, NL

+31-433870896

2

e.mcdonough@neu.edu Professor

International Business & Strategy Group College of Business Administration

Northeastern University Boston, MA 02115

+1- 617 373-4726 ABSTRACT

This study investigates the impact of leadership and an organization’s culture on the organization’s ability to exhibit innovation ambidexterity, i.e., the ability to simultaneously generate multiple types of innovation. We found that adaptive leadership had a direct and significant relationship on both internal process innovation and incremental product innovation. We also found that entrepreneurial and sharing organization cultures mediated the relationship between a bounded delegation style of leadership and internal process innovation, and incremental product innovation, and radical product innovation.

Our results suggest that the way in which leadership affects innovation is complex. While prior research has suggested that transformational leadership will foster radical innovation and that transactional leadership will foster incremental and internal process innovation, our findings suggest that this is a considerable oversimplification of the relationship between leadership and innovation. Our findings suggest that culture is crucial to enable innovation ambidexterity and further, that leadership and culture work in conjunction with each other to generate innovation. Thus, failing to take into account the role of organizational culture presents a distorted picture how leadership influences an organization’s ability to generate multiple types of innovation simultaneously.

Key words: Leadership, organization culture, innovation ambidexterity,

innovation, exploration, exploitation, Taiwan

INTRODUCTION

There is general agreement that innovation ambidexterity, i.e., the ability to simultaneously generate multiple types of innovation, plays a central role in sustaining a firm’s competitive success (Tushman & O’Reilly, 1996; O’Reilly &

Tushman, 2004; Gibson & Birkinshaw 2004). But as Markides & Chu (2008) point out “… whereas the need for and the beneficial effects of achieving ambidexterity have been recognized, little work has been done on exactly how organizations could achieve ambidexterity.” (pp. 3-4)

To date research on ambidexterity has focused on a handful of antecedents including, structure, context and leadership (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). Research on structural antecedents has focused on creating separate organization units and the use of formal and informal coordinating mechanisms to stimulate innovation ambidexterity (Duncan, 1976; Christensen 1997;

Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996; Jansen, et al., 2006), while research on context has focused on creating systems, processes, and beliefs that will enable and encourage individuals to judge for themselves how to best divide their time between different types of innovative activities (Gibson & Birkinshaw, 2004).

Research that has examined on leadership has focused on the role of top management teams (TMTs) in helping to create ambidexterity (Smith &

Tushman, 2005). Lubatkin, et al., (2006), e.g., has investigated the impact of the behavioral integration of TMTs on ambidexterity, while other research on TMTs has examined the impact of founding teams’ prior affiliations on innovative activities (Beckman, 2006).

Another antecedent that is thought to play an important role in fostering ambidexterity is leadership style. It has been proposed, e.g., that different leadership styles are needed in order to facilitate different types of innovation (Vera & Crossan, 2004; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004). These researchers have suggested that a participative form of leadership may be most helpful in fostering radical and discontinuous types of innovation, while an authoritative, top down style of leadership may be most helpful in fostering incremental innovation (Vera & Crossan, 2004, O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004). Interestingly, despite the importance ascribed to leadership (Vera & Crossan, 2004, O’Reilly

& Tushman, 2004), we are unaware of any empirical research that has specifically focused on the role of senior leadership style and its impact on fostering innovative activities leading to different types of innovation. Thus, one of the purposes of our study is to investigate the role of senior leadership styles, in fostering innovation ambidexterity.

Researchers have also raised the question of the respective roles of leaders

and organization culture in influencing innovation (Raisch and Birkinshaw,

2008). While some researchers have suggested that leadership and culture act

independently to affect innovation, others suggest that leadership operates

through an organization’s culture to influence innovation. Understanding how

leadership and culture interact to affect innovation ambidexterity is an important question that has not been investigated (Raisch and Birkinshaw, 2008).

Therefore, a second purpose of our study is to examine the interaction of leadership and an organization’s culture on the organization’s ability to foster innovation ambidexterity.

BACKGROUND Innovation

According to Garcia and Calantone (2002) and Grant (2002), innovation can be generally described as the quest for finding new ways of doing things.

Tidd et al., (2001), e.g., define innovation as “change” and include the creation and commercialization of new knowledge in terms of a firm’s generic innovation strategies (Porter, 1980), while Porter and Ketels (2003) define innovation as “the successful exploitation of new ideas”. As these definitions make clear, innovation is not limited to technological change or new products even though it is frequently described in this way.

Further, as the January 2008 report of The Advisory Committee on Measuring Innovation in the 21st Century Economy admonishes, “effective innovation measurement must go beyond tracking inputs such as R&D spending; it must also track outcomes for firms, customers, regions, and nations.” (Innovation Measurement: Tracking the State of Innovation in the American Economy, 2008). Recognizing the multi facetted nature of innovation, in our study we examine three types of innovation including, 1) internal process, 2) incremental product and 3) radical product innovation.

Product innovations have been characterized as falling along a continuum ranging from incremental (or continuous) to radical (or breakthrough) product innovation. Incremental new product innovations consist of product modifications, cost reductions, and product repositionings, while radical new product innovations are ones that incorporate substantially different technology from existing products and can fulfill key customer needs better than existing products (Chandy and Tellis, 1998).

In addition to product innovation, organizations can also undertake internal (to the organization) process innovation. This type of innovation is typically intended to improve organizational processes, work flows, or ways of working together to accomplish a company’s objectives (e.g., Davenport, 1993;

Bender et al., 2000). Internal process innovations are not intended for sale to other companies, but instead are intended for use internally by the organization to help it to work more effectively, generate greater efficiencies, increase speed of throughput, enhance communication flow, and the like. This type of innovation may come from any individual or department in the company.

It has been proposed that for organizations to be successful and effective

their senior leaders need to engage in behaviors that promote multiple types of

innovation (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004; March 1991).

Several researchers (cf., McDonough & Leifer, 1986; Vera & Crossan, 2004; O’Reilly & Tushman, 2004) have suggested that what has been called

“adaptive” leadership and “bounded delegation” leadership, may play a very important role in fostering different types of innovation. An adaptive leadership style is characterized as leadership that focuses on strategic thinking and organizational capabilities in adapting to circumstance change and aligning with business needs, while a bounded delegation leadership is characterized as the leadership coaching employees in line with organizational vision and goal but also providing support and wide latitude to inspire employees’ creativity.

Adaptive Leadership and Innovation

Leaders who exhibit an adaptive leadership style monitor the organization’s external environment, and use this information to keep the organization competitive and ensure continual organizational learning by adapting to variations in the external environments (Tushman, Anderson, &

O’Reilly, 1997; Boal and Hooijberg, 2000; Vera and Crossan, 2004). These leaders absorb, understand, and integrate new information and ideas and are sensitive to the needs of very different kinds of businesses and adapt to variations in the external environments (Tushman, Anderson, & O’Reilly, 1997;

Boal and Hooijberg, 2000).

Being immersed in the organization’s external environment enables these leaders to obtain customer feedback, learn of their customers’ problems and needs, and obtain market information, which they can then pass along to individuals in the organization. By facilitating this flow of information, this style of leadership helps to foster incremental, but not radical product innovation (Ulwick, 2002; Damanpour, 1991; Damanpour & Evan, 1984; Knight, 1967).

Unlike incremental innovations, radical innovation typically requires deep expertise and the exchange of more knowledge about specialized and leading edge technologies. Because such deep expertise usually comes about from intensive immersion in a specialized field, it is unlikely that adaptive leaders, whose job is to manage the company, not develop radically new products, will have been able to maintain either the deep expertise or knowledge that is needed to directly impact on radical innovation.

However, because these leaders serve as conduits for information between

customers and the organization, they are in a position to link customer needs and

problems with product development efforts within the organization. But,

innovation focused on meeting customer needs and solving customer problems

is incremental in nature. Radical innovation, on the other hand, is stimulated by

more basic technological and scientific investigation and is focused on

generating products that do not simply satisfy current customer needs, but rather

on offering new technologies to new markets.

Because of the adaptive nature of this leadership, with its focus on continual innovation, we also argue that adaptive leadership will impact on the organization’s ability to generate internal process innovations. The information that adaptive leaders bring into the organization from the external environment serves as a platform for innovation. It can inform the organization regarding the need to update the ways of doing things better and stimulate thinking about what new processes, workflows, and structures might look like. .

Thus, we propose that:

H1a: There will be a positive relationship between adaptive leadership and incremental product innovation.

H1b: There will be a positive relationship between adaptive leadership and internal process innovation.

Bounded Delegation Leadership and Innovation

While adaptive leaders may have a direct influence on innovation, we argue that leaders who exhibit what has been called a “bounded delegation”

style of leadership (McDonough & Leifer, 1986) have an indirect effect on innovation by working through an organization’s culture. Leaders with a bounded delegation style articulate goals for subordinates, but allow the subordinates to identify the path they wish to take to achieve those goals (McDonough & Leifer, 1986). Leaders who use such a style are closely connected to subordinates and provide coaching to ensure subordinates’ success, but refrain from specifying specific paths that subordinates should take to achieve their goals (McDonough & Leifer, 1986).

1Research on bounded delegation leadership suggests that these leaders foster innovation by providing a clear goal and support for creativity (McDonough & Leifer, 1986, Amabile et al., 1996, Mumford et al., 2002). An articulated goal provides an indication to followers of the importance of innovation and can increase their understanding of the goal’s importance. Such behaviors are likely to foster creativity, search, and sharing (McDonough &

Leifer, 1986; Amabile et al., 1996; McDonough & Griffin, 2000).

While innovation requires a leader to allow followers considerable freedom and tolerance to try new ideas and approaches, on the one hand, it also requires exerting a certain amount of control in order to ensure that ideas and approaches actually result in innovations, on the other (McDonough & Leifer, 1986). Successfully leading innovation demands that the leader bridge both ideation and business needs, and that they provide clear goals, while at the same time allowing wide latitude to achieve those goals. The wide latitude to achieve the goals involves providing support, as well as time and freedom for thinking and interacting with others (Amar, 1998; McDonough & Griffin, 2000; West et

1

Bounded delegation leadership is different from both transformational and transactional leadership.

Transformational leaders focus on making followers aware of the importance and value of task outcomes,

activate their higher-order needs, and induce them to transcend their self interest for the sake of the organization,

while transactional leaders specify behaviors for subordinates that should be used to achieve pre-ordained goals

al., 2003; Sosik et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2008).

Thus, by providing employees wide latitude in achieving the organization’s innovation goals and not constraining individuals regarding the paths they may take to achieve these goals, bounded delegation leadership helps to create an innovation enabling organization culture that will facilitate innovation, rather than impacting directly on innovation.

Organizational culture

Organizational culture has been defined as the basic beliefs commonly- held and learned by a group, that govern the group members’ perceptions, thoughts, feelings and actions, and that are typical for the group as a whole (Sackmann, 2003). It represents a complex pattern of beliefs, expectations, ideas, values, attitudes, and behaviors shared by the members of an organization that evolve over time (Trice & Beyer, 1984).

The Mediating Role of Organization Culture

Both theoretical discussion and empirical investigations suggest that the promotion of an innovation enabling culture requires senior leaders’ support and involvement (Drucker, 1985; Ireland & Hitt, 1999; Jassawalla & Sashittal, 2000;

Elenkov et al., 2005; Sosik et al., 2005; Uhl-Bien et al., 2007; Vera & Crossan, 2004). Farson & Keyes (2002), e.g., suggest that fostering failure tolerance is an important means of promoting an innovation enabling culture. And to foster failure tolerance requires that leaders are engaged, show interest in people’s work by asking pertinent questions, express support and give feedback, and are collaborative rather than controlling (Farson & Keyes, 2002).

This line of research (cf., Amabile, 1997; Farson & Keyes, 2002) suggests that leadership plays an instrumental role in fostering innovation by affecting the organization’s culture, within which individual behavior is manifested.

Amabile’s research (1997), e.g., suggests that leadership is crucial to provide the inclination for innovation in an organization. Leaders play an important role in developing an innovation-oriented company by supporting creativity through providing resources, e.g., sufficient time, training, coaching, and money.

Leaders also play an important role in encouraging new idea generation by providing individuals with the freedom to try new things and with challenging work. In this sense, creativity is the seed of innovation that requires watering by leaders. When a leader stimulates followers’ efforts to approach old situations in new ways, the leader entrepreneurial culture among followers that values creative thoughts, risk-taking approaches, and innovative work approaches (Jung et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2008).

By providing employees with opportunities to explore, investigate and experiment, bounded delegation leadership creates an entrepreneurial organization culture that fosters innovative behavior (Amabile et al., 1996;

Woodman et al., 1993; Sackmann, 2003, 2006; Ulwick, 2002; Anand et al.,

2007). In an entrepreneurial culture members of the organization identify opportunities and risks based on their perceptions of the internal and external organizational environment, integrate available resources, and bring in other individuals to enable them to undertake creative and innovative ventures (Sternberg, Kaufman & Pretz, 2003; Mumford & Licuanan, 2004; Chen, 2007).

Bounded delegation leaders also foster innovation by creating a sharing culture that facilitates interaction and information sharing among individuals across the organization (Damanpour, 1991; Ahmed, 1998; McDermott, 1999;

Menzel et al., 2008). This interaction and information sharing is an important means of allowing organization members’ views and opinions to be heard and for knowledge to be transferred (Menzel et al., 2008). Damanpour (1991) also suggests that internal communication is helpful to organizational innovativeness, while McDermott (1999) emphasizes that it is important to develop existing knowledge communities to facilitate information sharing. A sharing culture makes interaction, communication, and knowledge transfer possible (Damanpour, 1991; Ahmed, 1998; McDermott, 1999; Menzel et al., 2008), which in turn, encourages exploratory behavior and learning.

Once an entrepreneurial and sharing culture is created, there is no inherent reason to expect that the outcome of creative behaviors and knowledge transfer will be restricted to radical innovation. Indeed, we might expect that an entrepreneurial culture will allow for different levels of creativity and allow for the transfer of knowledge that is both more tacit and more explicit thus fostering all types of innovation.

Thus, in entrepreneurial and sharing cultures, individuals or groups are more inclined to take innovation initiatives (Amabile et al., 1996). Thus, we argue that such behavior is needed in order to generate innovation within the organization, including more radical innovation (McDonough & Leifer, 1986;

Amabile et al., 1996; McDonough & Griffin, 2000).

Hence, we propose that:

H2: Entrepreneurial and sharing organizational cultures mediate the relationship between bounded delegation leadership and incremental and radical product innovation, as well as internal process innovation.

In sum, we propose that an adaptive leadership will impact directly on incremental product and internal process innovation, while a bounded delegation leadership style will influence all three types of innovation indirectly by creating an organization culture that fosters innovation.

METHODOLOGY Research Design

The unit of analysis in the study is the strategic business unit (SBU). We

define an SBU as a profit center responsible for performance in one or more

markets with the authority to influence the choice of the business’ competitive strategy in its target markets. By focusing on the SBU, the likelihood that each respondent is well acquainted with the strategies, general processes, management, and performance of the SBU is increased (Narver et al., 2004).

Our study was set in Taiwan. Taiwan presents an interesting context for our study for at least two reasons. First, Taiwan has shown an innovation orientation in many aspects, e.g. Taiwan ranks number one in patents per million people granted between January 1 and December 31, 2007 and Taiwanese companies rank number 16 in the world in terms of R&D spending (World Economic Forum, Global Competitiveness Report 2008-2009). Thus, Taiwan provides an ideal context for a study that focuses on innovation. Second, Taiwan provides a unique context for studying the interplay between leadership styles and organizational culture. Taiwan is a country characterized by Western capitalism mixed with a Confucian orientation, which is manifested in many respects including management practices and individual behaviors.

Our sample consisted of 125 Taiwanese owned SBUs that were drawn from several industries including, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, financial management, mechanical engineering, and electronic engineering. As researchers have noted, innovation is more important to some industries than others (Jibu, et al., 2007). Thus, a majority of studies on innovation have investigated companies in the manufacturing, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, electronics, and financial service industries (cf., Atuahene- Gima, 1996; Elenkov et al., 2005; Jibu et al., 2007; Jung et al., 2008). Our sampling criteria included 1) the importance of innovation to the industry and 2) the importance of innovation to the company. Companies were contacted directly to ascertain their interest in participating in the study. Thus, our sample was a convenience sample of companies that fit the above criteria.

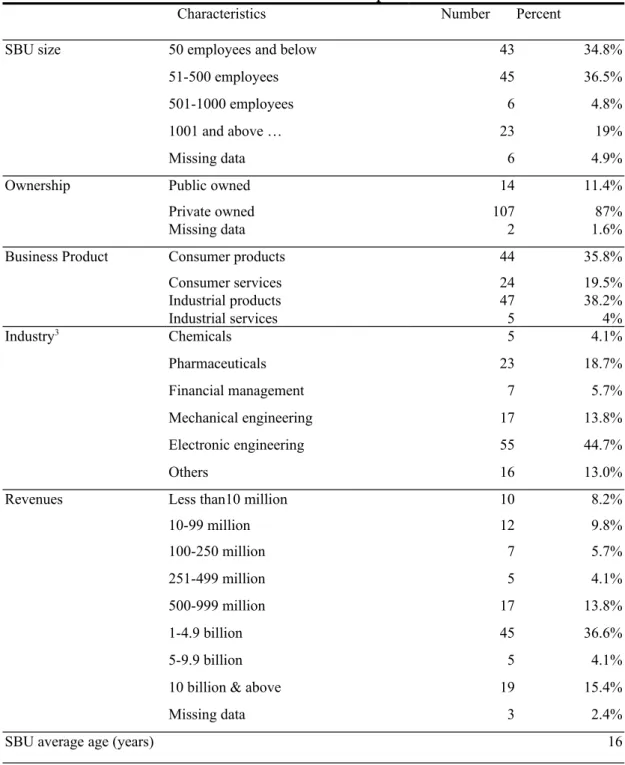

As shown in Table 1, size of SBU in our sample ranged from 45 employees to over 3,000. The mean size equaled 1,135. Average age of the SBUs in the sample was 16 years. One hundred and seven SBUs (87%) were privately owned. Thirty six percent of the SBUs in the sample are in the business of producing consumer products, 38% produce industrial products, 20% produce customer services, and 4% produce industrial products. Forty-five of the SBUs in our sample had revenues of 1 to 4.9 billion Taiwanese dollars (US$30 million to US$1.5 billion), seventeen SBUs had revenues of 500-999 million Taiwanese dollars (US$15-30 million) and nineteen SBUs had revenues of 10 billion Taiwanese dollars and above (US$3 billion).

2[Insert Table 1 about here]

A number of researchers (Podsakoff, et al, 2003; Jung et al. 2003; 2008;

Elenkov et al. 2005) suggest that respondents for independent and dependent

2

Conversion based on an exchange rate 1 US$ = 33 NTD

variables should be different in order to avoid self report and self evaluation that can result in common method bias. Thus, we developed one questionnaire to measure leadership and organization culture and a second questionnaire to measure innovation performance. In each SBU, a senior level manager was asked to fill out a questionnaire asking about the innovation performance of the SBU. Middle level managers were asked to fill out questionnaires that asked about senior manager leadership style and organization culture. A total of 320 respondents in 125 SBUs completed this questionnaire. The response rate for this study was 65% (125 SBUs participated out of the 190 that were initially approached).

Measures

Our instruments were originally constructed in English and were then translated into Chinese and back-translated into English to ensure the accuracy of the meaning of the questions. We also used a mixture of positive and negative questions in order to minimize response bias. The questionnaires were then pre- tested using a sample of managers in Taiwan. All constructs in this study were measured on a seven-point Likert type scale.

Innovation Performance. The measures of innovation performance were adapted from the work of Atuahene-Gima (2005) and Cooper &

Kleinschmidt (2000). Because senior managers are in the best position to provide responses to our questions concerning innovation performance, we asked these managers to look backwards over the past 3 years and provide their perceptions of innovation performance. We felt it was important to use a 3 year time period because of the lag effects that are likely to exist between leadership and its impact on innovativeness. Two items were used to measure internal process innovation. The items asked, “This SBU frequently implemented new internal processes in the last three years” and “Compared to your major competitor, this SBU implemented more new internal process innovations in the last three years”. These two items were combined into one factor. Incremental new product innovation was measured by 2 items, including, “This SBU frequently introduced incremental new products into new markets in the last three years” and “Compared to your major competitor, this SBU introduced more incremental new products in the last three years.” These two items were combined into one factor. Radical new product innovation was also measured by 2 items. “This SBU frequently introduced radical new products into new markets in the last three years” and “Compared to your major competitor, this SBU introduced more radical new products in the last three years.” These two items were also combined into one factor.

Senior Leadership Style. We asked middle managers to assess the

leadership style of senior leaders. Our measure of adaptive leadership was drawn

from the work of Boal and Hooijberg (2000) and consisted of three questions.

They identified the core of adaptive leadership as the creation and maintenance of absorptive capacity (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990) and adaptive capacity (Black

& Boal, 1996; Hambrick, 1989). Our measure of bounded delegation leadership consisted of three questions adapted from McDonough & Leifer (1986) and Avolio & Bass (1999).

To determine the number of items which contribute to common variance actually needed to describe leadership behaviors, we conducted common factor analyses on the bounded delegation and adaptive leadership dimensions.

Principal Components extraction with an Equamax rotation method (Eigenvalue

> 1) resulted in two factors, both of which closely paralleled the original dimensions. One factor consisted of three items representing bounded delegation leadership. The other factor consisted of three items representing adaptive leadership.

The measure of organization culture was adapted from the work of O'Reilly, Chatman, & Caldwell (1991) and consisted of six questions. The results of factor analysis on organizational culture yielded two factors. One factor consisted of 3 items representing an entrepreneurial orientation culture, while a second factor consisted of three items representing a sharing culture.

Control Variables. We included SBU/company size and industry as control variables because prior studies have documented their positive relationship with organizational innovation (cf., Hitt et al., 1997; Jung et al., 2003; Elenkov et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2008).

Aggregation of SBU-level variables. Keller (1986) points out that the aggregation of individual scores to the group level may be appropriate simply because the theory and hypotheses of a study require a certain level of analysis.

Thus, following Keller’s work (1986), we aggregated the member scores on each variable and computed the company or strategic business unit mean responses for each question. After aggregation, we followed Goodman et al.’s (1990) suggestion to justify the aggregation of SBU-level variables. We first used the inter-rater agreement index (γ

wg) to test within-SBU variance, and then used intra-class Correlation Coefficients (ICC) to test between-SBUs differences on each measure (e.g., James, Demaree & Wolf, 1993; Goodman et al., 1990).

The external reliability of SBU level measures was assessed by computing the value of inter-rater agreement for each measure using the γ

wgindex (James et al., 1993). The following γ

wgvalues were obtained, .63 for adaptive leadership, .65 for bounded delegation leadership, .67 for entrepreneurship oriented organizational culture, and .69 for sharing organizational culture. These γ

wgvalues were above the value of.60 that is conventionally accepted. For

constructs measured on a seven-point scale, the index ranges from –1.25 ≦γ

wg≦

1, indicating minimum and maximum acceptable agreement respectively (De

Luca & Atuahene-Gima, 2007). For each of the items the γ

wgindex fell between

–1.25 ≦γ

wg≦ 1.

We further employed intra-class correlation (ICC) to examine the degree of agreement among respondents on each measure. Values of .81 for adaptive leadership, .80 for bounded delegation leadership, .74 for entrepreneurship oriented organizational culture, and .72 for sharing organizational culture were obtained. All ICC values are greater than or equal to .60 indicating acceptable reliability (Schneider et al., 1998). The 95% level of confidence interval was calculated for each ICC to take sampling variation into account. For each of the items the ICC fell in the 95% level of confidence interval. Based on these results, aggregation was justified for these variables, and provided substantial support for the scales.

Measurement Validation. Following Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) suggestion, we performed a multistage process to further assess construct validity. We first examined correlations for each factor which derived from common factor analysis. Then, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test for the unidimensionality and convergent validity of the constructs. The scale items, along with factor loadings, reliability and model fit statistics, are shown in Table 2. Our CFA factor loadings (>=0.6) provide evidence of convergent validity. Next, we assessed discriminant validity of the constructs by testing if correlations between any two constructs were significantly different from unity. This required a comparison between two models in which one was constrained with the correlation equal to one and another was not. In each case discriminant validity was evidenced by the statistically significant chi-square differences between the models. Finally, we assessed the reliability of the constructs with Cronbach’s coefficient alpha. All scales have reliabilities greater than 0.70 (Cronbach’s α = 0.90, 0.89, 0.87, 0.85, 0.85, 0.94,and 0.91 for adaptive, bounded-delegation leadership, entrepreneurial, sharing organizational culture, and internal process, incremental, radical product innovation performance respectively).

[Insert Table 2 about here]

Several studies suggest the importance of testing two assumptions – linearity and homoscedasticity, when conducting multiple regression analysis (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Berry & Feldman, 1985). Because we used a bootstrapping procedure to test for mediating effect, there was no need to check assumptions of normality and multicollinearity (MacKinnon et al., 2004;

Preacher & Hayes 2004; 2008). To test linearity and homoscedasticity, standard

multiple regressions on each dependent variable were conducted. These yielded

the following results R =0.47, F =8.10, p=.000 < 0.001 for process innovation

performance, R =0.49, F =9.04, p=.000 < 0.001 for incremental product

innovation performance, and R =0.45, F =7.12, p=.000 < 0.001 for radical

product innovation performance. The shape of the normal scatter P-P plot of

regression-standardized residuals satisfied the rectangularity requirements for

linearity and homoscedasticity.

DATA ANALYSIS

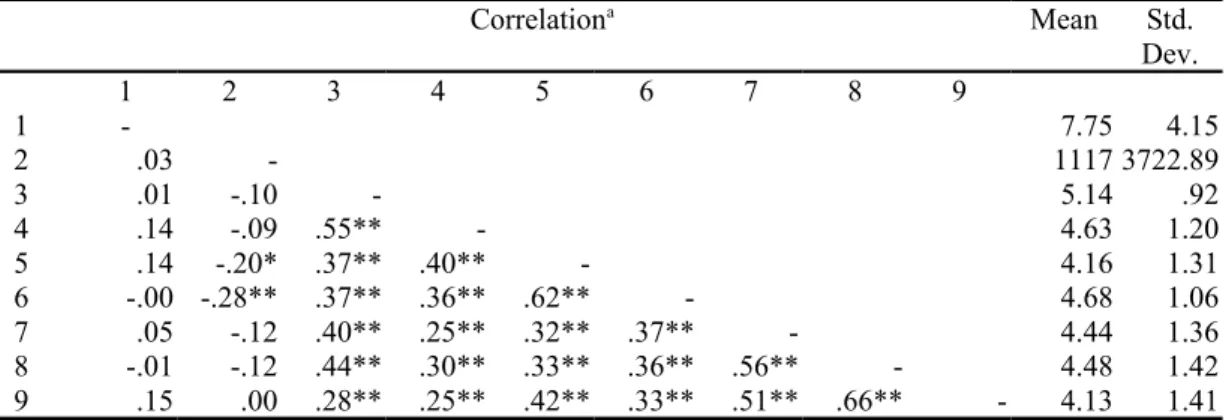

Table 3 provides descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations for all independent and dependent variables.

[Insert Table 3 about here]

The Effects of Leadership on Innovation Performance

Multiple regression analyses were performed to determine if there were significant relationships between each type of innovation and adaptive leadership, bounded delegation leadership, entrepreneurial organization culture, and sharing organization culture. We found that adaptive leadership was significantly related to incremental product innovation (H1a) and internal process innovation (H1b), providing support for Hypotheses 1a and 1b. As expected, there was no significant relationship between adaptive leadership and radical product innovation.

[Insert Table 4 about here]

In order to test the mediation hypotheses of organization culture on the leadership-innovation relationship, we followed Preacher & Hayes’s (2004) approach to directly test the significance of indirect effects in the mediation models. The approach combines the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) with a bootstrapping method to obtaining confidence intervals, as well as the traditional Baron and Kenny’s (1986) three-step approach criteria. We also used SPSS Macros provided by Preacher & Hayes (2004) to estimate the mediating effects.

We report the results of the Sobel test and each step of Baron and Kenny’s principals to provide powerful estimation in this study. Traditionally, the mediation analyses are most often guided by Baron & Kenny’s (1986) three- step procedures include, firstly, they indicate that regressing the mediator (i.e., entrepreneurial and sharing organizational culture) on the independent variable (i.e., bounded delegation leadership) should yield a significant result. Second, regressing the dependent variable on the independent variable needs to yield a significant result. Third, for mediation to exist, when the dependent variable is regressed on both the independent variable, i.e., leadership, and the mediator, i.e., organizational culture, the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable must not be significant, and the B value for the independent variable must be less in the third equation than in the second equation (cf. Baron

& Kenny, 1986, MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993).

We found that entrepreneurial and sharing cultures mediated the

relationship between bounded delegation leadership and incremental and radical

product innovation, as well as internal process performance, providing support for Hypothesis 2 (Table 5).

[Insert Tables 5 about here]

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

One of the purposes of this study was to examine the impact of leadership and an organization’s culture on the organization’s ability to generate innovation ambidexterity. Our results suggest that the way in which leadership affects innovation is complex. While earlier theoretical reasoning suggested simple relationships between transformational leadership and radical innovation, on the one hand, and transactional leadership and incremental and internal process innovation on the other, our findings suggest that this is a considerable oversimplification of the actual situation found in companies. It appears, based on what we found, that culture is crucial to enable innovation ambidexterity and further, that leadership and culture work in conjunction with each other. Thus, failing to take into account the role of organizational culture presents a distorted picture how leadership influences an organization’s ability to generate different types of innovation.

More specifically, we found that a bounded delegation style of leadership impacts on an organization’s culture, which in turn generates innovation, while an adaptive style of leadership directly facilitates incremental and internal process innovation. Further, the two types of leadership play important, but quite different roles in creating an innovation ambidexterity. With respect to promoting innovation, the same leadership style does not play an equally important role in bringing about each type of innovation. On the one hand, an adaptive style of leadership impacts on incremental product innovation and internal process innovation. On the other hand, a bounded delegation leadership style impacts, albeit indirectly, radical innovation.

Our findings also reinforce the notion that leadership and an organization’s culture are intimately intertwined and that both are needed in order to successfully generate innovation ambidexterity. Prior research has left unanswered the question about whether leadership or organization culture has a greater impact on innovation (cf., Halbesleben et al., 2003; Kets De Vries, 1996;

Sharma & Rai, 2003; Tierney, Farmer, & Graen, 1999; West et al., 2003;

Elenkov et al., 2005; Jung et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2008; Amabile, 1997). Some researchers have found a relationship between leadership and innovation (e.g., Stata, 1989; Tushman & Nadler, 1986; Mumford & Licuanan, 2004; Jung et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2008; Elenkov et al., 2005; Chen, 2007), while others have found that organizational culture is a major factor influencing innovation (e.g., Deal & Kennedy, 1982; Kotter & Heskett, 1992; Lee & Yu, 2004; Ouchi, 1980;

Ireland & Hitt, 1999; Jung et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2008).

The results from this study suggest that leadership and culture work in conjunction with each other, and provide additional insight into just how leadership and culture work together and for what purpose, when it comes to innovation. They propose that both leadership and organization culture play important roles in fostering innovation, but that the relative influence of leadership versus culture depends on the type of innovation being investigated.

Our study suggests that an organization’s culture can be used to foster all types of innovation, while leadership, and in particular adaptive leadership, can be used to directly foster incremental product and internal process innovation.

It is also important to emphasize that, while some of the literature on ambidextrous organizations suggests that leadership within organizations needs to be capable of shifting back and forth between a more transformational style of leadership and a more transactional style of leadership (Vera & Crossan, 2004), we believe that this does not reflect the reality facing the organizations that we studied. In these organizations, which were relatively small, innovation was a multidimensional activity, i.e., these organizations generated internal process innovations, incremental product innovations, and radical innovations - all at the same time. Indeed, “best practice” in the new product development literature suggests that organizations should develop a portfolio of innovation projects that include some that are more incremental and some that are more radical (McDonough & Spital, 2003). In most organizations, the innovation projects within this portfolio are undertaken simultaneously. At the same time, many argue that internal innovation needs to be a continuous activity (cf., Davenport, 1993; Bender et al., 2000). This implies that the organization’s leadership needs to enact different leadership styles simultaneously (McDonough & Leifer, 1983) that will lead to the creation of a variety of cultures that will foster these different types of innovation outcomes.

Our findings also suggest the importance of taking a “fine grained”

approach in order to understand more deeply and accurately how the leadership

of an organization and its culture influence the variety of types of innovation

that organizations need to generate. Such an approach entails investigating

multiple dimensions of leadership, organization culture, and multiple

dimensions of innovation, within the same study. We believe that by taking a

more “fine grained” approach this research has helped to clarify the

interrelationship between organization culture and leadership, as well as the

relationship between leadership and innovation ambidexterity. Beginning with

the work of March (1991), research has made clear the need for organizations to

exploit their current capabilities as a way of generating revenues and harvesting

the fruits of their innovative activities. At the same time however, simply

focusing on harvesting revenues from current products and innovative activity is

unlikely to lead to sustained competitive advantage. To maintain long run

competitive advantage organizations need to also continually investigate new

opportunities and develop new knowledge that will enable them to generate

leading edge innovations. Research that focuses on only one dimension of innovative activity, i.e., research that does not take a more fine grained approach by investigating multiple types of innovation, will only be able to provide a limited understanding of the interplay between product and process and incremental and radical innovation. As well, it will be limited in terms of its ability to provide insights into the factors driving each type of innovative activity, and into innovation ambidexterity.

It has also been pointed out recently that there has been virtually no research that has examined the international context impacting on ambidexterity research (Raisch & Birkinshaw, 2008). Yet, given the evidence of the impact of societal culture in other management areas of research (Hofstede, 1983; House et al., 2004; Sirmon & Lane, 2004; Elenkov et al., 2005), it is important to investigate whether the international context plays a role. The tendency for research on leadership and culture to focus on Western countries such as North America or Western Europe (Jackson & Schuler, 1995; Porter, 1985; Schuler, 1992; Wright & McMahan, 1992; Huselid, 1995; Elenkov et al., 2005), means that we have little understanding of what leadership styles affect different types of innovation in non-Western countries (for exceptions see, House & Aditya, 1997; Jung et al., 2003; Jung et al., 2008).

Prior research on the interaction between leadership and societal culture suggests that we might anticipate that leaders in Taiwanese organizations would exhibit leadership styles that are different from those exhibited by managers in Western companies. For example, in a study of leadership in Taiwanese companies, Jung, et al. (2003) found a negative relationship between empowerment and organizational innovation, thus suggesting that delegating more autonomy to employees results in less innovation. They speculate that in Taiwan’s culture with its relatively high in power distance (Hofstede, 2003), leaving employees alone with little guidance regarding how to accomplish goals may lead to confusion rather than innovation.

Our findings, however, contradict Jung, et al.’s in 2003. It is interesting to speculate on the extent to which the Confucian orientation that dominates in Taiwan may have more of an impact on behaviors versus power distance. It may be that Taiwan’s Confucian orientation accounts for the leaders in our study having a direct affect on generating incremental innovation and process innovation. Given the importance of hierarchy and respect for elders in the Confucian philosophy it may be that these leaders simply directed their subordinates to act on the customer feedback and market information that they had brought back into the organization. Given the Confucian orientation that is still prevalent in Taiwan, it would not be unreasonable to assume that such directives would be met with acceptance, unlike in more Western companies where such directive behavior would likely be seen as unpalatable.

This conclusion, however, is hard to reconcile with our finding that

organizational culture mediates the relationship between leadership and radical

innovation. How does the Confucian orientation allow for the generation of radical innovation? Creating a culture that will in turn lead to innovation means that the leader is playing an indirect or “hands-off” role. This seems contradictory to the notion of Confucian leaders as being controlling. One possible explanation is the highly competitive environment facing Taiwan that has undoubtedly raised these leaders’ awareness of the need to generate radical innovation, and the consequent need to rely on experts in the organization to help make this happen. Thus, it may be that when it comes to radical innovation, these leaders recognize the need for specialized expertise that they simply do not possess, thus “forcing” them to allow subordinates wide latitude in their search and learning processes. In this sense, it appears that the Western orientation of Taiwanese leaders comes to the fore.

Thus, our findings have implications for the actions that Taiwanese managers and perhaps non-Taiwanese managers as well, need to consider in order to facilitate innovation ambidexterity. Firstly, our findings suggest that leaders need to be sensitive to the type of innovation that they are trying to promote. But, they also need to be aware that while leadership can directly influence incremental and internal process innovation, in order to promote radical innovation leaders need to focus on creating a culture of innovation that will lead to the generation of radical innovations. Thus leaders need to be aware of the relative influence of leadership and organization culture on innovation.

Effectively creating innovation ambidexterity is not simply a matter of employing leadership styles or creating an organization culture. Instead, it is a matter of knowing when to use one or the other in order to foster all types of innovation.

Clearly, there is a need for further study to investigate exactly how leaders actually promote innovative activities among their subordinates. While cross sectional research is useful, we need to add the more dynamic perspective that real-time case studies could provide. Because our sample focused on organizations in Taiwan, generalizability of the results is limited. Thus, there is also a need to replicate this study in Western organizations, as well as in non- Western, emerging economies in order to more systematically investigate how cultural heritage influences leadership behaviors and decision-making and their impact on innovation performance.

This study is limited as well as a consequence of our having investigated

only a few dimensions of innovation performance, leadership, and organization

culture. Thus, we can provide only an incomplete picture of the role of

leadership and culture in affecting innovation. This calls for more research that

looks at additional aspects of these variables. But, by taking a more fine grained

approach to investigating the relationships among leadership, organization

culture and innovation our study has made clear the need for future research to

include multiple dimensions of each of these variables in their investigations. As

well, it makes clear the importance of examining each leadership style

separately in order to understand each style’s effect on innovation performance,

and each style’s interactions with other factors, including organization culture,

as they influence innovation performance.

References

1. Ahmed, PK. 1998. Culture and climate for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management 1(1): 30-43.

2. Amabile, TM et al., 1996. Assessing the work environment for creativity.

Academy of Management Journal 39: 1154-1184.

3. Amabile, TM. 1997. Motivating creativity in organizations: on doing what you love and loving what you do. California Management Review 40(1): 39- 58.

4. Amar, AD. 1998. Leading Innovating Organizations. The Mid-Atlantic Journal of Business 34(3): 185-187.

5. Anand, N, Gardner, HK, Morris, T. 2007. Knowledge-based innovation:

emergence and embedding of new practice areas in management consulting firm. Academy of Management Journal 50(2): 406-428.

6. Anderson, JC, Gerbing, DW. 1988. “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A review and recommended two-step approach”. Psychological Bulletin 103(3): 411-423.

7. Atuahene-Gima, K. 1996. Differential Potency of Factors Affecting Innovation Performance in Manufacturing and Services Firms in Australia.

Journal of Product Innovation Management 13(1): 35-52.

8. Atuahene-Gima, K. 2005. Resolving the Capability–Rigidity Paradox in New Product Innovation, Journal of Marketing 69: 61–83.

9. Avolio, BJ, Bass, BM. 1999. Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire. Journal of Occupational & Organizational Psychology 72(4): 441-462.

10.Baron, RM, Kenny, DA. 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Consideration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51(6): 1173- 1182.

11.Beckman, CM. 2006. The influence of founding team company affiliations on firm behavior. Academy of Management Journal 49(4): 741-758.

12.Bender, KW et al., 2000. Process innovation – case studies of critical success 13.factors. Engineering Management Journal 12(4): 17-24.

14.Berry, WD., & Feldman, S. 1985. Multiple Regression in Practice. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

15.Black, JA, Boal, KB. 1996. Assessing the organizational capacity to change.

In A. Heene & R. Sanchez (Eds.), Competence-based strategic management 151-169. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

16.Boal, KB, Hooijberg, R. 2000. Strategic Leadership Research: Moving On.

Leadership Quarterly, 11(4): 515-549.

17.Chandy, RK, Tellis, GJ. 1998. “Organizing for Radical Product Innovation:

The Overlooked Role of Willingness to Cannibalize”. Journal of Marketing Research, 35 (November): 474–87.

18.Chen, MH. 2007. Entrepreneurial Leadership and New Ventures: Creativity in Entrepreneurial Teams. Creativity and Innovation Management 16(3):

239-49.

19.Cohen, J, Cohen, P. 1983. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd edition). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

20.Cohen, WM, Levinthal, D. 1990. "Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation", Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 128-152.

21.Cooper, RG, Kleinschmidt, EJ. 2000. New product performance: what distinguishes the star Products. Australian Journal of Management 25(1).

22.Christensen, CM. 1997. The Innovator's Dilemma. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

23.Damanpour, F. 1991. Organizational innovation: a meta-analysis of effects of determinants and moderators. Academy of Management Journal 34(3): 555- 590.

24.Damanpour, F, Evan, WM. 1984. Organizational innovation and performance: The problem of organizational lag. Administrative Science Quarterly 29: 392-409.

25.Davenport, TH. 1993. Process Innovation. Reengineering Work through Information Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

26.Deal, TE, Kennedy, AA. 1982. Corporate Cultures. Reading, MA: Addison- Wesley.

27.De Luca, LM, Atuahene-Gima, K. 2007. Market knowledge dimensions and cross-functional collaboration: Examining the different routes to product innovation performance. Journal of Marketing, 71: 96-112.

28.Drucker, PF. 1985. The discipline of innovation. Harvard Business Review, 63(3): 67-72.

29.Duncan, RB. 1976. The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. In Kilmann, RH., Pondy, LR., & Slevin, DP., (eds.), The management of organization: Strategy and implementation 1:

167-88. New York: North Holland.

30.Elenkov, D, Judge, W, Wright, P. 2005. Strategic leadership and executive innovation influence: an international multi-cluster comparative study.

Strategic Management Journal 26: 665-682.

31.Garcia, R, Calantone, R. 2002. A critical look at technological innovation typology and innovativeness: a literature review. The Journal of Product Innovation Management 19: 110-132.

32.Gibson, CB, Birkinshaw, J. 2004. "The Antecedents, Consequences, and

Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity," Academy of Management

Journal 47(2): 209-26.

33.Goodman, PS, Ravlin, EC, Schminke, M. 1990. Understanding groups in organizations. In L.L.Cummings & B.M. Staw (Eds.). Leadership, participation, and group behavior: 323-385. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

34.Grant, RM. 2002. Contemporary Strategic Analysis: Concepts, techniques, applications. 4

thed. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K.

35.Halbesleben, JRB et al., 2003. The influence of temporal complexity in the leadership of creativity and innovation: A competency-based model.

Leadership Quarterly 14:433-454.

36.Hambrick, D. 1989. Guest editor’s introduction: Putting top managers back in the strategy picture. Strategic Management Journal 10: 5-15.

37.Hitt, MA, Hoskisson, RE, Kim, H. 1997. International diversification:

Effects on innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms.

Academy of Management Journal 40: 767-798.

38.Hofstede, G. 1983. National cultures in four dimensions: A research-based theory of cultural differences among nations. International Studies of Management & Organization 13(1-2): 46-74.

39.Hofstede, G. 2003. Culture’s and Organizations: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival. Software of the Mind. 2

ndEd. Great Britain, Profile Books Ltd.

40.House, RJ, Aditya, R. 1997. The social scientific study of leadership: Quo vadis? Journal of Management 23: 409-474.

41.House, RJ et al., 2004. Culture, leadership, and organization: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA.

42.Huselid, MA. 1995. The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal 38: 635-672.

43.Ireland, RD, Hitt, MA. 1999. Achieving and maintaining strategic competitiveness in the 21

stcentury: the role of strategic leadership. Academy of Management Executive 13(1): 43-57.

44.Jackson, SE, Schuler, RS. 1995. Understanding human resource management in the context of organizations and their environments. Annual Review of Psychology, 46, 237-264.

45.James, LR, Demaree, RG, Wolf, G. 1993. Rwg: An Assessment of within- Group Interrater Agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology 78: 306-309 46.Jansen, JJP, van den Bosch, FAJ, Volberda, HW. 2006. Exploratory

innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science 52(11): 1661-1674.

47.Jassawalla, AR, Sashittal, HC. 2002. Strategies of effective new product team leaders. California Management Review, 42(2): 34-51.

48.Jibu, M et al, 2007. Special Feature: Fostering Open Innovation. Global

Innovation Ecosystem 2008. Fostering innovation for economic development

and sustainability. Tech Monitor: 17-23. Sep-Oct.

49.Jung, DI, Chow, C, Wu, A. 2003. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. The Leadership Quarterly 14: 525-544.

50.Jung, DI, Wu, A, Chow, C. 2008. Towards understanding the direct and indirect effects of CEOs' transformational leadership on firm innovation. The Leadership Quarterly 19(5):582-594.

51.Keller, R. 1986. Predictors of the performance of project groups in R&D organization. Academy of Management Journal 29: 715-26

52.Kets De Vries, M. 1996. Leaders who make a difference. European Management Journal 14(5): 486-493.

53.Knight, KE. 1967. A descriptive model of the intra-firm innovation process.

Journal of Business 40: 478-496.

54.Kotter, JP, Heskett, JL. 1992. Corporate Culture and Performance. New York, NY: Free Press.

55.Lee, SK, Yu, K. 2004. Corporate culture and organizational performance.

Journal of Managerial Psychology 19(4): 340-359.

56.Levinthal, D, March, J. 1993. Myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal 14: 95-112.

57.Lubatkin, MH et al., 2006. Ambidexterity and performance in small- to medium- sized firms: The pivotal role of top management team behavioral integration. Journal of Management 32(5): 646-672.

58.MacKinnon, DP, Dwyer, JH. 1993. Estimating Mediated Effects in Prevention Studies. Evaluation Review 17(2): 144-158.

59.March, JG. 1991. Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning.

Organization Science 2: 71-87.

60.Markides, CC, Chu, W. 2008. Innovation through Ambidexterity: How to Achieve the Ambidextrous Organization, London Business School working paper.

61.McDermott, R. 1999. Why information technology inspired but cannot deliver knowledge management. California Management Review 41(4): 103- 127.

62.McDonough III, E, Leifer, RP. 1983. “Using Simultaneous Structures to Cope with Uncertainty,” Academy of Management Journal 26: 727-35.

63.McDonough III, EF, Leifer RP. 1986. Effective Control of New Product Projects: The Interaction of Organization Culture and Project Leadership.

Journal Product Innovation Management 3:149-157.

64.McDonough III, EF, Griffin, A. 2000. Creating systemic capability for consistent high performance new product development. In Jürgens, U. (ed.), New Product Development and Production Networks - Learning from Experiences in Different Industries and Countries, Berlin: Springer, 441-458.

65.McDonough, EF, Spital, FC. 2003. "Managing the NPD Project Portfolio."

Research*Technology Management, 40-46.

66.Menzel, HC et al., 2008. Developing Characteristics of an Intrapreneurship Supportive Culture, In: A. Fayolle and P. Kyroe (Eds.), The Dynamics between Entrepreneurship, Environment and Education, Cheltenham (UK):

Edward Elgar, pp. 77-102.

67.Mumford, MD et al., 2002. Leading creative people: Orchestrating expertise and relationships. Leadership Quarterly, 13: 705-750.

68.Mumford, MD, Licuanan, B. 2004. Leading for innovation: Conclusions, issues and directions. Leadership Quarterly 15: 163-171.

69.Narver, JC, Slater, SF, MacLachlan, DL. 2004. Responsive and proactive market orientation and new-product success. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 21: 334-347.

70.O’Reilly III, CA, Chatman, J, Caldwell, DF. 1991. People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organizational fit. Academy of Management Journal 34(3): 487-516.

71.O’Reilly III, CA, Tushman, ML. 2004. The Ambidextrous Organization.

Harvard Business Review (Apr), 82(4): 74-81.

72.Ouchi, WG. 1980. "Markets, Bureaucracies, and Clans," Administrative Science Quarterly 25, 129-141.

73.Podsakoff, PM et al., 2003. Common Methods Bias in Behavioral Research:

A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies, Journal of Applied Psychology 88(5): 879-903.

74.Porter, ME. 1980. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. The Free Press, New York, U.S.A.

75.Porter, ME. 1985. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: Free Press

76.Porter, ME, Ketels, C. 2003. UK Competitiveness – Moving to the next stage. DTI Economics Paper No.3, May 2003.

77.Preacher, KJ., & Hayes, AF. 2004. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 36: 717-731.

78.Preacher, KJ., & Hayes, AF. 2008. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models.

Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879-891.

79.Raisch, S, Birkinshaw, J. 2008. Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management 34(3): 375-409. June 80.Sackmann, SA. 2003. Cultural complexity as a challenge in the management

of Global Companies. In Mohn, L. (ed.), A Cultural Forum Vol. III, Corporate Cultures in Global Interaction. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation, 58-81.

81.Sackmann, SA. 2006. Success Factor: Corporate Culture: Developing a

Corporate Culture for High Performance And Long-term Competitiveness

Six Best Practices. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation.

82.Schneider, B, White, SS, Paul, MC. 1998. Linking service climate and customer perception of service quality: Test of causal model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83:150-163.

83.Schuler, RS. 1992. Strategic human resource management: Linking people with the needs of the business. Organizational Dynamics 21(1): 18-32.

84.Sharma, S, Rai, A. 2003. An assessment of the relationship between ISD leadership characteristics and IS innovation adoption in organizations.

Information and Management 40(5): 391-401.

85.Sirmon, DG, Lane, PJ. 2004. A model of cultural differences and international alliance performance. Journal of International Business Studies 35: 306-319.

86.Smith, WK, Tushman, ML. 2005. Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organization Science 16: 522-536.

87.Sobel, ME. 1982. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982 (pp. 290-312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

88.Sosik, JJ et al., 2005. Making all the right connections: The strategic leadership of top executives in high-tech organizations. Organizational Dynamics 34(1): 47-61.

89.Stata, R. 1989. Organizational learning - the key to management innovation.

Sloan Management Review,. 30(3), 63-74.

90.Sternberg, RJ, Kaufman, JC, Pretz, JE. 2003. A propulsion model of creative leadership. Leadership Quarterly 14(4-5): 455-473.

91.Tidd, J, Bessant, J, Pavitt, K. 2001. Managing Innovation: Integrating technological, market and organizational change. 2

nded. John Wiley & Sons, Chicester, England, U.K.

92.Tierney, P, Farmer, S, Graen, G.. 1999. An examination of leadership and employee creativity: the relevance of traits and relationships. Personnel Psychology 52: 591-620.

93.Trice, HM, Beyer, JM. 1984. Studying organizational cultures through rites and ceremonials. Academy of Management Review 9(4): 653-669.

94.Tushman, M, Nadler, D. 1986. Organizing for innovation. California Management Review, 28(3), 74-93.

95.Tushman, ML, O’Reilly III, CA. 1996. “Ambidextrous organizations:

Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change”, California Management Review 38(4): 8-30.

96.Tushman, ML, Anderson, PC, O’Reilly, C. 1997. “Technology cycles,

innovation streams, and ambidextrous organizations: organizational renewal

through innovation streams and strategic change.” In Tushman, ML. and

Anderson, PC., Managing strategic innovation and change: a collection of

readings. Oxford University Press, New York.

97.Uhl-Bien, M, Marion, R, McKelvey, B. 2007. Complexity leadership theory:

Shifting leadership from industrial age to the knowledge era. Leadership Quarterly 18: 298-318.

98.Ulwick, AW. 2002. Turn customer input into innovation. Harvard Business Review. January.

99.Vera, D, Crossan, M. 2004. Strategic leadership and organizational learning.

Academy of Management Review 29(2): 222-240.

100. West, MA et al., 2003. Leadership clarity and team innovation in health care. Leadership Quarterly 14: 393-410.

101. Woodman, RW, Sawyer, J, Griffin, RW. 1993. Toward a theory of organizational creativity. Academy of Management Review 18(2): 293-321.

102. Wright, PM, McMahan, GC. 1992. Theoretical Perspectives for Strategic

Human Resource Management. Journal of Management 18: 295-320.

Table 1 Sample Profile

Characteristics Number Percent

SBU size 50 employees and below 43 34.8%

51-500 employees 45 36.5%

501-1000 employees 6 4.8%

1001 and above … 23 19%

Missing data 6 4.9%

Ownership Public owned 14 11.4%

Private owned 107 87%

Missing data 2 1.6%

Business Product Consumer products 44 35.8%

Consumer services 24 19.5%

Industrial products 47 38.2%

Industrial services 5 4%

Industry

3Chemicals 5 4.1%

Pharmaceuticals 23 18.7%

Financial management 7 5.7%

Mechanical engineering 17 13.8%

Electronic engineering 55 44.7%

Others 16 13.0%

Revenues Less than10 million 10 8.2%

10-99 million 12 9.8%

100-250 million 7 5.7%

251-499 million 5 4.1%

500-999 million 17 13.8%

1-4.9 billion 45 36.6%

5-9.9 billion 5 4.1%

10 billion & above 19 15.4%

Missing data 3 2.4%

SBU average age (years) 16

N 125

Note: 1) missing data means no answer from respondent. 2) for revenue, the currency in Taiwan is new Taiwan dollars. Conversion based on an exchange rate 1 US$ = 33 NTD.

Table 2. Construct Measurement and Confirmatory Factor Analyses by AMOS

3