Investigating the relationship between service

providers’ personality and customers’

perceptions of service quality across gender

Neng-Pai Lin,

1Hung-Chang Chiu

2& Yi-Ching Hsieh

31

Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2

Department of International Trade, Ming Chuan University, Taipei, Taiwan &3Department of Business Administration, Soo Chow University, Taipei, Taiwan

abstract The main objective of this paper is to examine the relationship between the personality of the service providers and the service quality performance they provide. The Five-Factor model of personality and the SERVQUAL model of service quality were used to substantiate the hypothesized relationship. Empirical data from 143 pairs of employees and customers indicate that employees with diVerent personality traits perform diVerently on customers’ perception of service quality. The results indicated that openness correlated with assurance, conscientiousness was a valid predictor of reliability, extraversion was positively related to responsiveness, and agreeableness signi® cantly correlated with both empathy and assurance. Moreover, the relationship between personality and service quality was moderated by customers’ gender. Overall, the outcome of this study can be applied to personnel allocation in accordance with the service quality strategy of a company.

Introduction

Past research has suggested that service providers play an important role in customers’ evaluation of the service quality of a business (e.g. Heskett, 1987; Heskett et al., 1994; Mattson, 1994; Tansuhajm et al., 1988). Few of these studies, however, have examined the relationship between service providers’ characteristics and the service quality performance they provide. The present study, therefore, intends to ® ll this research gap by examining the relationship between the personality of the service providers and the perceived service quality. Although previous studies have con® rmed the relationship between the personality traits of employees and the job performance, the job evaluation criteria of these studies, however, were mostly evaluated by the employees’ supervisors, peers, or employees themselves (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Cellar et al., 1996; Cortina et al., 1992; Crant, 1995; Gellatly, 1996; Hayes

et al., 1994; Salgado, 1997; Tett et al., 1991). Few of these studies appraised employee

performance from a customer’s perspective. To a service business, delivering a high-quality service that meets customers’ needs is an important way to achieve competitiveness (Holmlund & Kock, 1996; Parasuraman et al., 1988). Service providers’ performance evaluated by customers, therefore, should be emphasized in the service industry.

Correspondence: Neng-Pai Lin, Department of Business Administration, National Taiwan University, Taipei,

Taiwan. E-mail: nengpai@handel.mba.ntu.edu.t w

ISSN 0954-4127 print/ISSN 1360-0613 online/00/010057-11 2001 Taylor & Francis Ltd DOI: 10.1080/09544120020010093

Diþ erent customer gender may also aþ ect the perception of service quality. Men are generally more aggressive and autonomous than women (Hoþ man & Hurst, 1990), they tend to be highly exploratory (Pulkkinen, 1996). As such, if a service provider oþ ers services to a female customer, she might feel uncomfortable, however, it might not be the case for a male customer.

In addition, managers often select only some important dimensions of service quality to have strategic quality management to compete with other companies (Garvin, 1987). Therefore, if a manager understands the relationship between service provider’s personality and the delivery of service quality perceived by customers across gender, he/she can improve service quality performance by allocating competent personnel in accordance with the service quality strategy of the company. For example, to gain female customers’ trust, managers of a real-estate agency may allocate the employees who are more trustworthy, rather than talkative, to serve their customers. The objective of this study is, therefore, to examine the relationship between the personality of the service providers and the customers’ perception of service quality across gender.

Background

Personality

Personality can be de® ned as ``those characteristics of the person that account for consistent patterns of behavior’’ (Pervin, 1993). Diþ erent personality theories have been developed over the years to explain the structure, process and development of human behavior. They include psychoanalytic theory, phenomenological theory, cognitive theory, trait theory, learning theory and social cognitive theory. Since the purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between the service providers’ personality and the perception of their customers, we thus focus only on the understanding of the service providers’ personality structure. Among these above personality theories, trait theory tends to place a great emphasis on exploring the basic structure of personality.

Over the past four decades, a number of personality psychologists have investigated the basic dimensions of personality. Trait theorists assume that people possess broad predispositions, called traits, that cause them to behave in a particular way (Pervin, 1993). These theorists believe traits are the basic units of personality.

Eysenck’s early research regarded neuroticism and extraversion as the basic dimensions of personality, or the ``Big Two’’ (Digman, 1990). He developed the Maudsley Personality Inventory (or MPI) based on these two traits. The scholar, later added psychoticism as the third dimension to interpret human personality (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1975). Similarly, Cattell determined the dimensions of personality by analyzing three types of data: life record data (L-data), questionnaire data (Q-data) and objective test data (OT-data). He then found 16 personality factors obtained from these data (Pervin, 1993). The major result of Cattell’s research was a questionnaire called the Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (Cattell, 1973).

Norman (1963) used the factor analysis technique to extract the basic personality factors from Cattell’s reduction of natural language trait terms. He suggested the ® ve factors extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability and culture were the adequate taxonomies of personality attributes. This was the beginning of the Five-Factor model (FFM). In another attempt, Costa and McCrae (1985) considered the viewpoints of Eysenck and Norman, and proposed that the following ® ve dimensions: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness were the fundamental units of personality. They also developed the NEO Personality Inventory to measure these factors.

Recently, there has been growing agreement among personality theorists that there are ® ve robust and basic dimensions of personality (e.g. Cellar et al., 1996; Costa & McCrae, 1985; Digman, 1990; McCrae & John, 1992; Pervin, 1993; Salgado, 1997). They called it the FFM, or the Big-Five. These ® ve factors are neuroticism (N) or emotional stability, extraversion (E) or surgency, conscientiousness (C), agreeableness (A), and openness (O)Ð OCEAN for short ( John, 1990; Pervin, 1993).

The neuroticism factor of personality mainly assesses a person’s emotional instability. Traits associated with this factor include being angry, anxious, depressed, touchy, unstable and worried (Barrick & Mount, 1991; McCrae & John, 1992). The extraversion factor mainly assesses the intensity of interpersonal interaction, activity level and capacity to enjoy. Common characteristics associated with this factor are active, aþ ectionate, energetic, optimistic, oriented, sociable and talkative (Pervin, 1993). Traits commonly associated with conscientiousness include planning, being careful and organized, responsible, self-disciplined and thorough (Barrick & Mount, 1991; McCrae & John, 1992). Agreeableness represents the quality of an individual’s interpersonal orientation along a continuum from compassion to antagonism in thoughts, feelings and action (Pervin, 1993). Traits frequently associated with this dimension include being appreciated, forgiving, generous, kind, sympathetic and trusting (McCrae & John, 1992; Pervin, 1993). The openness dimension of personality assesses proactive seeking and appreciation of experience for one’s own sake (Pervin, 1993). Traits frequently associated with the openness dimension of personality include being broad-minded, creative, curious, imaginative, intelligent, original and perceptive (Barrick & Mount, 1991; McCrae & John, 1992; Pervin, 1993).

To assess these dimensions, researchers have developed diþ erent questionnaires to measure the ® ve constructs derived from trait theory. For example, Costa and McCrae (1985, 1992) have developed a NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI) and NEO-PIR, a revised version of NEO-PI. Goldberg (1992) has also proposed the bipolar and unipolar adjective markers. A brief version of Goldberg unipolar adjective markers, called the Mini-Marker, was developed by Saucier (1994). These questionnaires have demonstrated a reasonable reliability and validity.

Service quality

Researchers have de® ned quality in diþ erent ways. This quality construct has been variously de® ned as value (Feigenbaum, 1951), conformance to requirements (Crosby, 1979), ® tness for use ( Juran et al., 1974) and meeting customers’ expectations (Parasuraman, Zeithaml & Berry, 1985) (hereafter PZB). However, because of the increased importance of the service sector, researchers are de® ning quality from a customer’s perspective. Among services marketing literature, the widely used de® nition of service quality is to meet customers’ expectations de® ned by PZB (1985). PZB (1985), in their review of the quality theory literature, found service quality could be neither conceptualized nor evaluated by the traditional methods of goods quality because services possess three characteristics: intangibil-ity, heterogeneity and inseparability (PZB, 1985, 1988, 1991). For this reason, they have de® ned and conceptualized service quality as a form of attitude, which results from a comparison of customers’ expectations with perceptions of performance. They have also developed an instrument called SERVQUAL to measure service quality.

The SERVQUAL scale is based on a gap model (PZB, 1985), which suggests the gap between customers’ expectations and their perceptions of actual performance drives the perception of service quality. Both the original version of SERVQUAL (PZB, 1988) and its revised version (PZB, 1991, 1994) contain ® ve dimensions of tangibles, reliability,

responsiveness, assurance and empathy. The dimension of tangibles assesses the extent of the appearance of a company’s physical facilities, equipment and personnel. Reliability measures the ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately. Respons-iveness represents the willingness to help customers and provide a prompt service. Assurance assesses the knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to inspire con® dence. Empathy measures the caring and individualized attention the ® rm provides to its customers (PZB, 1988). These ® ve dimensions were derived from 10 overlapping dimensions, which were regarded as essential to service quality by PZB’s (1985) exploratory research. Although the SERVQUAL instrument has been criticized by some researchers (e.g. Carman, 1990; Cronin & Taylor, 1992; Teas, 1993), it is still the leading measure of service quality (Lam & Woo, 1997; Mittal & Lassar, 1996).

Relationship between personality traits and service quality

About three decades ago, a majority of researchers studied the validity of personality scales for personnel selection purposes (Barrick & Mount, 1991). At that time, the overall conclusion of those studies was that the validity of personality as a job performance predictor was very low (e.g. Ghiselli, 1973; Guion & Gottier, 1965; Locke & Hulin, 1962). However, as discussed earlier, there was no consensus among trait theorists on classifying personality traits then. Recently, the relationship between employees’ personality traits and their job performance has been widely discussed in personality psychology literature because of the emergence of the Big-Five (e.g. Barrick & Mount, 1991; Cellar et al., 1996; Cortina et al., 1992; Crant, 1995; Gellatly, 1996; Hayes et al., 1994; Salgado, 1997; Tett et al., 1991). Most of these studies, however, evaluated job performance by the employee’s supervisors, peers, or the employee him/herself. Few of them used a customer’s perception of service quality, which is considered to be as a crucial a factor for success in service industry as job performance. It is, therefore, important to evaluate service providers’ performance from a customer’s point of view.

Gender diVerences in behavior

Past studies have suggested that women show a relatively high tendency of emotion, lack of con® dence (Fisk & Stevens, 1993) and stress in the workplace (Babin & Boles, 1998). Research has also suggested the existence of gender-based diþ erences in behavior in decision-making. For example, there is evidence supporting the view that women are more risk-averse than men in ® nancial decision-making (Powell & Ansic, 1997). In addition, as pointed out by Hoþ man and Hurst (1990), men are expected to be relatively more aggressive and autonomous than women. Pulkkinen (1996) also suggests that men tend to show a high exploratory tendency while women exhibit a greater passiveness. If these inherent gender diþ erences aþ ect human behavior, it is logical to assume that female and male customers would probably evaluate their service providers in diþ erent ways.

Methodology

Conceptual framework

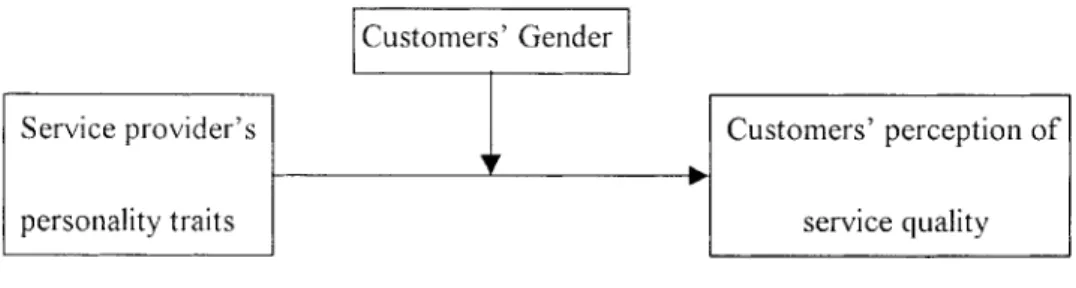

As mentioned earlier, in this study, it was intended to explore the relationship between service providers’ personality and customers’ perceptions of service quality. In addition, gender diþ erences would probably aþ ect customers’ decisions when service providers were

Figure 1. Research model.

evaluated. Therefore, the relationship between service providers’ personality and customers’ perceptions of service quality is probably moderated by customers’ gender. Figure 1 represents the conceptual framework of this study.

Measures

This study used two major instruments for measuring the dimensions of personality and service quality. First, the Mini-Marker instrument developed by Saucier (1994) was used to assess the Big-Five personality dimensions of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism. The reason for using the 40-item Mini-Marker is because both the NEO-PIR developed by Costa and McCrae (1992) containing 240 items and the unipolar adjective markers developed by Goldberg (1992) consisting of 100 items are too lengthy. Furthermore, the Mini-Marker uses only eight adjectives to measure each of the ® ve personality factors with reasonable reliability, and it can be completed within 5 minutes. The format of response to the items was a nine-point Likert-type scale. Respondents were required to indicate how much they possessed the personality traits described by each adjective (1, extremely inaccurate; 2, very inaccurate; 3, moderately inaccurate; 4, slightly inaccurate; 5, neutral; 6, slightly accurate; 7, moderately accurate; 8, very accurate; 9, extremely accurate). To conceptualize service quality, the second instrument used in this study was the latest 21-item version of SERVQUAL (PZB, 1994). This inventory measures the ® ve dimensions of reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy and tangibles. Among the ® ve dimensions of service quality in SERVQUAL, the tangibles dimension contains ® ve items, which are `convenient business hour’, `modern equipment’, `visually appealing facility’ , `employees who have a neat, professional appearance’ and `visually appealing materials associated with the service’ (PZB, 1994). Since this dimension mainly assesses the extent of the appearance of a company’s physical facilities, equipment and personnel (PZB, 1988), there exists little relationship between the tangibles dimension and employee’s personality. We thus deleted the ® ve items associated with this dimension in SERVQUAL and only measured 16 items to assess the other four dimensions of service quality. Additionally, perceptions-only (P) score rather than gap score (P± E) was used to conceptualize service quality since the perceptions-only scale was the best measure when maximizing predictive power is the major objective (PZB, 1994). The response format of the items was also a nine-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely disagree) to 9 (extremely agree).

To ensure a minimization of idiomatic wording, both of the Mini-Marker and SERVQUAL instruments were ® rst translated into Chinese and then checked by translating back to English. Moreover, both the Mini-Marker and SERVQUAL instruments were self-administered.

Data collection

The data used in the present study were collected in Taiwan (mostly in Taipei) from four diþ erent service sectors: life insurance, real-estate agencies, information services and securi-ties. A total of 143 pairs of questionnaires were returned, leading to the following sample sizes of the four service categories: life insurance, 50; real-estate agencies, 24; information services, 31; and securities, 38. The reason for choosing these four categories is that a customer would always accept the company’s services from the same service provider in the above categories. The customer, therefore, who evaluated the degree of the company’s service quality depended mainly on a particular service provider’s behavior, which re¯ ects his/her personality. Besides, the responses were analyzed by pooled data (i.e. data from the above four categories considered together) rather than separately. This is because the purpose of this study was to investigate the relationship between service providers’ personality and customers’ perceptions that would be reliable in a variety of service sectors.

To minimize the sampling bias, participants of the service providers were asked to choose randomly at least three to ® ve customers they had served as the sampling frames of the customers. From each sampling frame, we randomly selected one customer to assess the service quality he/she perceived as the service quality performance of the employee. The customer was asked to mail the questionnaire directly to the authors after ® lling in the questionnaire and did not pass through that service provider. This process was designed to prevent the customers from favorable evaluation to please their service providers. On the other hand, the instructions in the questionnaires reminded the respondents of service providers that they should describe themselves as objectively as possible. Meanwhile, the service providers were also asked to return the questionnaires directly to the authors so that their supervisors would not be able to read their questionnaires. This process was to ensure the validity of the Mini-Marker.

Analysis

Reliability and factor structure

To examine whether the factor structures of the Mini-Marker and SERVQUAL (excluding tangibles dimension) in this study re¯ ected the same factors found in the original analyses, we conducted two factor analyses. Using the con® rmatory factor analyses, we analyzed the raw scores of both Mini-Marker and SERVQUAL by the maximum likelihood method and restricted the number of factors to ® ve for the Mini-Marker and four for the SERVQUAL (excluding tangibles dimension) as originally proposed. We then rotated them using the varimax procedure. The coeý cient alphas of the Mini-Marker and SERVQUAL were 0.78 and 0.97, respectively. The ® nal communality values in both Mini-Marker and SERVQUAL also suggested these that two instruments possessed the same factor structures as originally proposed. These results indicated both instruments used in this study possessed a reasonable reliability and construct validity.

Relationship between personality and service quality

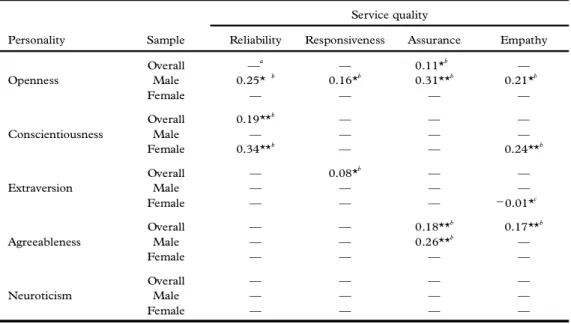

To investigate a possible relationship between of the service providers’ personality and the customers’ perception of service quality across gender, three second-order multivariate regression models were performed for the sample of 64 males, 79 females and the overall 143 customers, respectively. The reason for using the second-order model is that there might exist a classic ideal point (or non-linear relationship) when a customer assessed service quality

Table 1. Standardized coeYcients resulting from three regressions of service quality dimensions on personality factors

Service quality

Personality Sample Reliability Responsiveness Assurance Empathy

Overall Ð a Ð 0.11*b Ð Openness Male 0.25* b 0.16*b 0.31**b 0.21*b Female Ð Ð Ð Ð Overall 0.19**b Ð Ð Ð Conscientiousness Male Ð Ð Ð Ð Female 0.34**b Ð Ð 0.24**b Overall Ð 0.08*b Ð Ð Extraversion Male Ð Ð Ð Ð Female Ð Ð Ð 2 0.01*c Overall Ð Ð 0.18**b 0.17**b Agreeableness Male Ð Ð 0.26**b Ð Female Ð Ð Ð Ð Overall Ð Ð Ð Ð Neuroticism Male Ð Ð Ð Ð Female Ð Ð Ð Ð *p < 0.10; **p < 0.05. a

Predictor is not signi® cant when p < 0.10.

b

Linear relationship.

c

Second-order polynomial relationship.

(Teas, 1993). These three separate second-order polynomial models were all using four of the SERVQUAL dimensions (excluding tangibles) as the dependent variables and the Big-Five personality dimensions as the predictors. The composite scores were calculated for each dimension of personality and service quality by summing their respective items. Since the independent variable X and its square value (X2) often correlate highly in this kind of

polynomial regression model, we centered the predictor variable (i.e. xi5 Xi2 XÅ ) so that the

multicollinearity could be reduced substantially (Neter et al., 1996). Table 1 shows the results obtained from three multivariate regressions of personality dimensions on service quality dimensions.

As indicated in Table 1, for the sample of overall 143 respondents, it is clear that the openness factor is a valid predictor of assurance ( p < 0.10), conscientiousness correlates with reliability ( p < 0.05), extraversion is positively correlated with responsiveness ( p < 0.10) and the agreeableness dimension signi® cantly correlates with both assurance and empathy ( p < 0.05). These relationships between the personality factors and service quality dimensions can be explained as follows.

The openness factor of personality assesses proactive seeking and appreciation of experience for one’s own sake. Past studies have indicated that openness is a valid predictor of training pro® ciency because it assesses the employee’s readiness to participate in learning experiences (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Employees who score high on this factor are, therefore, more likely to have working knowledge and ability to deliver trust to customers. As such, openness appears to be a valid predictor of assurance. As to the personality dimension of conscientiousness, recent studies show this factor is a valid predictor of job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991; Gellatly, 1996; Salgado, 1997). Employees who score highly on these traits are, therefore, more likely to perform the promised service more dependably and accurately than those who score low. Conscientiousness thereby tends to be positively

correlated with reliability. The extraversion factor of personality mainly assesses the intensity of interpersonal interaction, activity level and capacity to enjoy. Recent research indicates that extraversion appears to predict job performance involving social interaction (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Since employees with a higher score of extraversion are apt to deal with customers more aþ ectionately, actively and talkatively than those with a lower score, the extraversion factor of personality, therefore, tends to be positively related to the responsiveness dimensions of service quality. Agreeableness represents the quality of one’s interpersonal orientation along a continuum from compassion to antagonism in thoughts, feelings and action. Traits frequently associated with this dimension include being appreciated, forgiving, generous, kind, sympathetic and trusting (McCrae & John, 1992; Pervin, 1993). Accordingly, employees who score highly on this dimension will probably perform better on empathy than those who score low. Moreover, Salgado (1997) has suggested that agreeableness was a valid predictor of training pro® ciency. Employees with a higher score on this factor are, therefore, apt to have more working knowledge, which leads to conveying more trust and con® dence to customers. As such, agreeableness tends to correlate with both assurance and empathy.

Furthermore, it is obvious from the sample of 64 male customers in Table 1 that openness is the most important factor for a service provider since it is positively related to the four dimensions of service quality ( p < 0.10), and agreeableness signi® cantly correlates with assurance ( p < 0.05). The reason for openness being the most important factor might be the eþ ect of similarity. A considerable amount of research has suggested that similarity among individuals in a relational context in¯ uences the satisfaction of relationship (Crosby

et al., 1990). As such, since men tend to score slightly higher on openness than women for

the Chinese sample (Feingold, 1994), male customers are likely to perceive higher perfor-mance when the service providers are openness. Finally, for the 79 female customers, conscientiousness is an important personality factor because it is positively related to reliability ( p < 0.05) and empathy ( p < 0.05). The reason for the above relationship is also likely to be similarity. Since women are relatively more conscientious (Pulkkinen, 1996), female cus-tomers are likely to perceive higher performance when the service providers are conscientious. There also exists a curvilinear relationship between extraversion and empathy for female customers in this study ( p < 0.10). The reason for the second-order polynomial relationship between extraversion and empathy for female customers might be that not everyone assessed the service scores in the same way on the empathy dimension according to the degree of an employee’s active and sociable attitude. For example, if an employee aggressively delivered too much care to a female customer, she might feel uncomfortable and hence score low on the empathy dimension. Such conditions would be more likely to occur in a Chinese society, which has a more conservative culture than the West. That is, for female customers, we favored a more realistic explanation, raised by Teas (1993), that a classic ideal point (curvilinear relationship) existed when a customer assessed service quality.

From Table 1, it is clear that the neuroticism factor, which mainly assesses one’s emotional instability, is not a valid predictor of any dimension of service quality. This result might be true for two reasons. First, respondents with highly emotional instability might worry about their questionnaires being read by their supervisors, thereby tending to choose more positive adjectives to describe themselves. Such conditions would be more likely to occur for the female service providers, who tend to exhibit a relatively high tendency of emotion, lack of con® dence (Fisk & Stevens, 1993), anxiety (Feingold, 1994) and increased stress (Babin & Boles, 1998). The second reason might be due to a type of range restriction based on a `selecting-out’ process (Barrick & Mount, 1991). The selecting-out process means those employees who are highly emotionally unstable cannot work eþ ectively and, as a result, are not likely to be in the labor force (Barrick & Mount, 1991). Those employees who were highly neurotic, therefore, were already excluded from our sample.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, many personality psychologists have discussed the relationship between the personality of employees and their job performance. Few, however, have adopted the customers’ perception, which is considered to be an important factor in service industry in determining the performance of employees. This study was, therefore, to explore the relationship between service providers’ personality and their service quality perceived by customers. The result suggests that the relationship between personality and service quality is moderated by gender. For the sample of overall customers, openness is a valid predictor of assurance, conscientiousness correlates with reliability, extraversion is positively correlated with responsiveness, and agreeableness is a valid predictor of assurance and empathy. As for male customers, openness is the most important factor for the service provider since it is a valid predictor of all dimensions of service quality, and agreeableness signi® cantly correlates with assurance. Finally, for the sample of female customers, conscientiousness is an important factor for the service provider because it is a valid predictor of reliability and empathy. Moreover, there exists a curvilinear relationship between extraversion and empathy for female customers. If managers can make clear the relationship between personality and service quality, they may improve service quality performance by allocating suitable service providers to serve customers.

Future research of this study can take the following directions. First, more studies should be undertaken to examine the relationship between service providers’ personality traits and their service performance. Although results in this study indicate personality is a valid predictor of service quality, however, researchers can use other personality instruments (such as NEO-PI), diþ erent service sectors, or diþ erent samples to re-examine these results in the future.

In addition, we have raised another important issue that there exists a curvilinear relationship between extraversion and empathy for the sample of Chinese women. In other words, service providers who actively delivered too high levels of empathy to female customers might lead to lowering the performance of the empathy dimension. Such a non-linear relationship can be investigated further under diþ erent cultures.

Acknowledgement

This research has been ® nancially supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan under NSC 86± 2417-H-002± 006.

References

Babin, B.J. & Boles, J.S. (1998) Employee behavior in a service environment: a model and test of potential diþ erences between men and women, Journal of Marketing, 62, pp. 77± 91.

Barrick, M.R. & Mount, M.K. (1991) The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: a meta-analysis, Personnel Psychology, 44, pp. 1± 26.

Carman, J.M. (1990) Consumer perceptions of service quality: an assessment of the SERVQUAL dimensions,

Journal of Retailing, 66, pp. 33± 55.

Cattell, R.B. (1973) Personality pinned down, Psychology Today, pp. 40± 46.

Cellar, D.F., Klawsky, J.D. & Miller, M.L. (1996) The validity of personality, service orientation, and reading comprehension measures as predictors of ¯ ight attendant training performance, Journal of Business

and Psychology, 11, pp. 43± 54.

Cortina, J.M., Doherty, M.L., Schmitt, N., Kaufman, G. & Smith, R.G. (1992) The Big Five personality-factors in the IPI and MMPIÐ predictors of police performance, Personnel Psychology, 45, pp. 119± 140.

Costa, P.T., Jr & McCrae, R.R. (1985) The NEO Personality Inventory Manual (Odessa, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources).

Costa, P.T., Jr & McCrae, R.R. (1992) Discriminant validity of NEO-PIR facet scales, Educational and

Psychological Measurement, 52, pp. 229± 237.

Crant, J.M. (1995) The proactive personality scale and objective job-performance among real-estate agents,

Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, pp. 532± 537.

Cronin, J.J., Jr & Taylor, S.A. (1992) Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension, Jour nal of

Marketing, 56, pp. 55± 68.

Crosby, L.A., Evans, K.R. & Cowles, D. (1990) Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal in¯ uence perspective, Journal of Marketing, 54, pp. 68± 81.

Crosby, P.B. (1979) Quality is Free: The Art of Making Quality Certain (New York, New American Library). Digman, J.M. (1990) Personality structure: emergence of the Five-Factor model, Annual Review of Psychology,

41, pp. 417± 440.

Eysenck, H.J. & Eysenck, S.B.G. (1975) Manual of Eysenck Personality Inventory (San Diego, CA, EDITS). Feigenbaum, A.V. (1951) Quality Control: Principles, Practice, and Administration (New York, McGraw-Hill). Feingold, A. (1994) Gender diþ erences in personality: a meta-analysis, Psychological Bulletin, 116, pp. 429± 456. Fisk, S.T. & Stevens, L.E. (1993) What’s so special about sex? Gender stereotyping and discrimination. In: S. Oskamp & M. Costanzo (Eds) Gender Issues in Contemporary Society (Newbury Park, CA, Sage Publications), pp. 173± 196.

Garvin, D.A. (1987) Competing on the eight dimensions of quality, Harvard Business Review, 65, pp. 101± 109. Gellatly, I.R. (1996) Conscientiousness and task-performanceÐ test of a cognitive process model, Journal of

Applied Psychology, 81, pp. 474± 482.

Ghiselli, E.E. (1973) The validity of aptitude tests in personnel selection, Personnel Psychology, 26, pp. 461± 477.

Goldberg, L.R. (1992) The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure, Psychological Assessment, 4, pp. 26± 42.

Guion, R.M. & Gottier, R.F. (1965) Validity of personality measures in personnel selection, Personnel

Psychology, 18, pp. 135± 164.

Hayes, T.L., Roehm, H.A. & Castellano, J.P. (1994) Personality correlates of success in total quality manufacturing, Journal of Business and Psychology, 8, pp. 397± 411.

Heskett, J.L. (1987) Lesson in the service sector, Harvard Business Review, 65, pp. 118± 126.

Heskett, J.L., Jones, T.O., Loveman, G.W., Sasser, W.E., Jr & Schlesinger, L.A. (1994) Putting the service± pro® t chain to work, Harvard Business Review, 72, pp. 164± 174.

Hoffman, C. & Hurst, N. (1990) Gender stereotypes: perception or rationalization, Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 58, pp. 197± 208.

Holmlund, M. & Kock, S. (1996) Relationship marketing: the importance of customer-perceived service quality in retail banking, Service Industries Journal, 16, pp. 287± 304.

John, O.P. (1990) The ``Big Five’’ factor taxonomy: dimensions of personality in the nature language and in questionnaires In: L.A. Pervin (Ed.) Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (New York, Guilford Press), pp. 66± 100.

Juran, J.M, Gryna, F., Jr & Bingham, R.S. (1974) Quality Control Handbook (New York, McGraw-Hill). Lam, S.K. & Woo, K.S. (1997) Measuring service quality: a test± retest reliability investigation of SERVQUAL,

Journal of the Market Research Society, 39, pp. 381± 396.

Locke, E.A. & Hulin, C.L. (1962) A review and evaluation of the validity studies of activities vector analysis,

Personnel Psychology, 15, pp. 25± 42.

Mattson, J. (1994) Improving service quality in person-to-person encounters: integrating ® ndings from a multi-disciplinary review, Service Industries Journal, 14, pp. 45± 61.

McCrae, R.R. & John, O.P. (1992) An introduction to the Five-Factor model and its applications, Journal of

Personality, 60, pp. 175± 215.

Mittal, B. & Lassar, W.M. (1996) The role of personalization in service encounters, Journal of Retailing, 72, pp. 95± 109.

Neter, J., Kutner, M., Nachtsheim, C. & Wasserman, W. (1996) Applied Linear Statistical Models, 4th Edn (Chicago, Irwin).

Norman, W.T. (1963) Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attribute: replicated factor structure in peer nomination personality rating, Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 66, pp. 574± 583. Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. & Berry, L.L. (1985) A conceptual model of service quality and its

implications for future research, Journal of Marketing, 49, pp. 41± 50.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. & Berry, L.L. (1988) SERVQUAL: a multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perceptions of service quality, Journal of Retailing, 64, pp. 12± 40.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. & Berry, L.L. (1991), Re® nement and reassessment of the SERVQUAL scale, Journal of Retailing, 67, pp. 420± 450.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. & Berry, L.L. (1994) Alternative scales for measuring service quality: a comparative assessment based on psychometric and diagnostic criteria, Journal of Retailing, 70, pp. 201± 230.

Pervin, L.A. (1993) Personality: Theory and Research, 6th Edn (New York, John Wily).

Powell, M. & Ansic, D. (1997) Gender diþ erences in risk behavior in ® nancial decision-making: an experimental analysis, Journal of Economic Psychology, 18, pp. 605± 628.

Pulkkinen, L. (1996) Female and male personality styles: a typological and development analysis, Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70, pp. 1288± 1306.

Salgado, J.F. (1997) The Five-Factor model of personality and job-performance in the European-community,

Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, pp. 30± 43.

Saucier, G. (1994) Mini-MarkersÐ a brief version of Goldberg unipolar Big-Five markers, Journal of Personality

Assessment, 63, pp. 506± 516.

Tansuhajm, P., Randall, D. & McCullough, J. (1988) A services marketing management model: integrating internal and external marketing functions, The Journal of Service Marketing, 2, pp. 31± 38.

Teas, R.K. (1993) Expectations, performance evaluation and customers’ perceptions of quality, Journal of

Marketing, 57, pp. 18± 34.

Tett, R.P., Jackson, D.N. & Rothstein, M. (1991) Personality measures as predictors of job performance: a meta-analytic review, Personnel Psychology, 44, pp. 703± 742.