青少年透過新通訊科技與父母溝通之行為:探索家庭關係的關

鍵影響因素與結果

凃張伯謙、林承宇

摘要

行動通訊對於「數位原生代」的日常生活已是不可或缺的使用工具;過去相關議 題研究大多著重於青少年使用新媒體科技後的負面影響,鮮少關注其對家庭關係影響 層面的探究。據此,本研究發展出一套實證模式探索青少年使用新媒體科技與父母溝 通的動機、關係維繫與親密關係為何,以瞭解青少年使用新媒體科技為家庭帶來了何 種影響。根據307份有效樣本的統計結果,顯示青少年主要以即時通訊與父母聯繫, 而此較能激勵青少年對父母表達自身的感覺與信賴感;其「居住區域」與「家庭溝通 模式」亦會間接影響青少年與父母溝通的動機、關係維繫與親密關係的感知。此模式 同時印證了新媒體科技對鞏固青少年與家庭親密程度能發揮極大的輔助作用。 ⊙ ☉ 關鍵字:青少年、新媒體科技、家庭溝通模式、關係維繫、親密關係 ⊙ ☉ 本文第一作者張伯謙為世新大學傳播管理學系副教授;第二作者林承宇為世新大學通識教 育中心副教授。 ⊙ ☉ 通訊作者為林承宇,聯絡方式:Email :cyou.lin@msa.hinet.net;通 訊 處:00116台北市文 山區木柵路一段17巷1號S1111研究室。 ⊙ ☉ 收稿日期:2016/12/20 接受日期:2017/12/03Adolescents' Use of Information and Communication

Technologies for Communication with Parents: The Key

Determinants and Consequences of Family Relationship

Po-Chien Chang & Cheng-Yu Lin

Abstract

The widespread Internet and mobile access to new technologies has affected adolescents’ daily lives. Prior studies have attributed the influences of emerging technologies to the negative effects of adolescent behavior, while little attention was given to the results of family relationships. Drawing from the perspectives of communication motives and family relationships, this study develops an empirical model by investigating the connections between adolescents’ communication motives and their perceptions of relational maintenance and intimacy with their parents.

A group of 307 adolescents were surveyed and analyzed by statistical methods. The results show that adolescents prefer using instant messaging to communicate with their parents, which motivates them to express their feelings and assurances. In addition, geographical location and family communication patterns affect adolescents’ perceptions of communication motives, relational maintenance, and intimacy. Finally, the empirical model is proved to not only compare the adolescents’ perceptions of using different media in family communication but also reveal the consequences that correspond to the parent– adolescent dyads relationships. The implications are expected to consolidate adolescent-parent relationships through the complement of new communication media.

⊙

relational maintenance, intimacy

⊙

☉Po-Chien Chang is an Associate Professor in Department of Communications

Management at Shih Hsin University. The second author, Cheng-yu Lin, is an Associate Professor in the Center for General Education, Shih Hsin University.

⊙

☉Corresponding author: Cheng-yu Lin, e-mail: cyou.lin@msa.hinet.net, address: Room S1111, No.1, Lane 17, Sec.1, Mu Cha Road, Taipei, Taiwan.

⊙

Introduction

The widespread and mobile access to new technologies has affected adolescents’ daily lives. They are labeled as digital natives or the n-generation (Tapscott, 2009). Prior studies have argued that most adolescents squander their time in online communities and have reduced the amount of time spent in communicating with friends and family members in person, and thus created negative effects such as Internet addiction, relational isolation, and family conflicts. The phase of adolescence in the process of human development is normally fragile and sensitive and it requires much attention from parents to understand the importance of communication technologies in family relationships.

In addition, within the field of media effect, in recent years scholars have continued to investigate the influences of new media technologies on media users, ranging from TV, personal computer, to Internet and mobile phones (Carvalho, Francisco, & Relvas, 2015). However, the communication contexts and content vary when compared to face to face and online communication (Ledbetter, 2009b; Lundy & Drouin, 2016). The conclusions are not capable of explaining the effects derived from new technologies and the consequences of adolescence, such as the levels of relational satisfaction, intimacy and media usage patterns. The family relationship of adolescents, measured by the frequency and duration of using the new technologies does not explain the interrelations of the family members, technology uses, and adolescents’ behavior. Different results have been published based on constant evaluations of adolescents’ access to various technologies (Blackshaw, 2009; Boase, Horrigan, Wellman, & Rainie, 2006; Lenhart, Madden, Macgill, & Smith, 2005; Macgill, 2007). According to a survey by Pew Internet Project in 2013, over half of adolescents use smartphones and spend more time online than with their parents (Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013). Other studies also show both adolescents and parents’ use of technologies are subject to the differences in gender, age, family income, and parents’ education (Brown, Childers, Bauman, & Koch, 1999). More parents and adolescents regard new technologies as a tool to communicate with others (Boase et al., 2006; Lenhart et al.,

2005; Macgill, 2007; Madden et al., 2013; Schwartz, 2004), which motivate us to explore this topic in detail.

The conclusions of the impact of new technologies on adolescents tend to be more negative than positive. Scholars argued that adolescents are overly immersed in virtual communities based on the conditions of time and frequency and lack of communication and relational development with the physical world (Mesch, 2003; Nie, Hillygus, & Erbring, 2002; Subrahmanyam & Greenfield, 2008). In contrast, the lack of physical cues might yield more benefits for people to express their inner thoughts and emotions by avoiding physical contact with others (Riva, 2002). Schwartz (2004) offered some advantages of computer-mediated communication between adolescents and parents, such as eliminating tensions, more organized thoughts, or new ways of communication by filtering the non-verbal cues. In Taiwan, long school hours and activities have created invisible pressure and tensions toward relationships between adolescents and parents. The adolescents’ use of new technologies has been described to deteriorate their relationships in the family in terms of more addition to technologies and less contact with parents. However, studies of adolescents’ use of new technologies have been accredited to the investigation of adolescents’ attitude and behavior toward the use of new technologies (Su, 2011). Prior study of adolescent-parent relationship is scarce and further investigation of this relationship in a mediated communication is yet to be revealed (Huang, Li, & Wang, 2014). The reluctant of foreseeing the impact of new technologies intervention within adolescent-parent relationship may result in the lacks of diversity in family and communication research. Acknowledging the emerging requests to assess the intervention of new media technology and the impact of family relationships, the aim of this study is to develop an empirical model to understand the intention of new technologies utilized by adolescents, which results in their motivations and relationships with parents.

of family communication is associated with positive development of adolescents’ capabilities in different perspectives, such as attachment, social comprehensions, and abilities of cognition and emotion (Vuchinich, Ozretich, Pratt, & Kneedler, 2002). Olson (1993) defines positive adolescent–parent communication as when either adolescents or parents can utilize the communication skills to maintain the family relationships and increase the adaptabilities and cohesion of family members, and thereby establish a healthy family environment. Most family studies explored the connections between communication media and results of relationships rather than interactive processes and behaviors. Their scopes of exploration are also limited to a specific family group, such as spouse, sibling, and adolescents rather than the dyads relationship between adolescents and parents. Vogl-Bauer, Kalbfleisch, and Beatty (1999) considered whether the adolescents’ or parents’ strategies of relational maintenance would influence how they communicate with each other and the consequences of their relationships. Potential indicators can also be drawn from external factors, such as media usage, family communication patterns or individual differences can be assumed to direct the adolescents’ motivations and relationships while communicating with parents online (Ledbetter, 2008, 2009b, 2014; Schrodt et al., 2009).

Adolescent-parent communication in the use of new media technologies

Like other generation, scholars consider the uses of new technologies, such as the Internet and social networking sites, are mainly for communication and maintaining relationship with others (Carvalho et al., 2015). Hence, most studies argue that adolescents would seek support and relational ties through online communications with peers (Gunuc & Dogan, 2013; Lee, 2009; Lenhart et al., 2005). New patterns of communication can be established by the emergence of new technologies that people use, which also make prior studies adjust their framework based on the use contexts of new technologies (Lenhart, Lewis, & Rainie, 2006)

Lee (2009) summarized the related works on Internet use by adolescents and concludes with four principles: substitution, reinforcement, consolidation, and social compensation.

Prior studies that support the principle of substitution argue the time spent on new technology has occupied the time span on social life and directing the feelings of individuals (Gunuc & Dogan, 2013; Kraut et al., 2002; Mesch, 2003; Nie et al., 2002). In contrast to the viewpoint of substitution, the scholars who support the principle of complement believe that people can expand new relationships and intimacy with others, which are irrelevant to their usage on the Internet. According to their findings, adolescents’ feeling of family communication and social support increase along with the increase of online usage (Mesch, 2003). Following the principle of consolidation, scholars conclude that adolescents’ online relationships can be consolidated in combination with their existing social network. In other words, adolescents may feel a stronger need to contact with peers after online communications with the same groups. Finally, the principle of social compensation is attributed to the adolescents’ personality. Adolescents who are introverted and socially anxious can gain help from the applications of new media technologies, such as E-mail and instant messaging, to expand their peer communication and relationships. Hence, researchers are in consensus that the adolescents’ usage of new technology and development in their personal relationships are complex. Insights of connections between technology usage and adolescents’ relationships can be comprehended by comparing different communicators, technologies, level of relationships, and results (Carvalho et al., 2015; Mesch & Talmud, 2006).

The motivations of interpersonal communication

To further understand the determinants that family members communicate with each other, prior studies applied theories from social psychology, such as Motivation Theory (Dweck & Leggett, 1988) or Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) (Ajzen & Madden, 1986) to understand how individuals create motivations through the needs of cognitions and provide an overall assessment based on the surrounding environment and personal abilities toward generations of human behaviors. Meanwhile, individuals are inclined to utilize tools or resources to satisfy their needs, which are assumed to be goal-oriented. Hence, it

their behaviors in the use of new technologies. Originated from Motivation Theory, Schutz (1966) and Rubin, Perse, and Barbato (1988) incorporate the needs of others and develop the scales for measuring the individuals’ motivations of interpersonal communication. Schutz (1966) believes that people interact with each other because they want to satisfy their needs from others. Hence, he believed there are three motivations that initiate from interpersonal communication, such as inclusion, control and affection. Later, Rubin et al. (1988) added three interpersonal motives: pleasure, escape and relaxation.

According to the original scales of interposal communication motives by Rubin et al. (1988), six dimensions are illustrated as pleasure, affection, inclusion, inclusion, escape, relaxation, and control. The measurement of interpersonal communication motives are also verified by other scholars to achieve both reliability and validity (Barbato & Perse, 1992; Graham, Barbato, & Perse, 1993; Martin & Anderson, 2009; Myers, Brann, & Rittenour, 2008).

Relational maintenance

The initiation and termination of interpersonal relationships is a gradual development evolved with different time spans and formats of interactions. Altman and Taylor (1973), in their theory of social penetration, use the profile of an onion to show the width and depth of personal relationships. The process of interpersonal relationships is involved with relational establishment, reinforcement, maintenance, delusion, and termination. Through message communication and self-disclosure, individuals are capable of increasing or maintaining relationships with others. It is also critical to verify the causal links between interpersonal communication and relational maintenance. The applications of such connections can be also applied to specific groups of communicators, such as spouses, friends, and relatives (Canary, Stafford, Hause, & Wallace, 1993; Dindia & Canary, 1993). Unlike the subjects in prior studies, adolescence is a stage of human development with huge transitions in both physical and psychological aspects. Hence, the adolescents’ relational maintenance with parents is requires further attention (Thorton, Orbuch, & Axinn, 1995). Stafford and Canary

(1991) propose the development of relational maintenance in two dimensions: the phases of relationship, referred to as the four stages of human relationship, and the relational strategy, which people utilize to connect with the others. The composition of relational maintenance consists of five dimensions: positivity, openness, assurance, social network, and task sharing. Synthesized from prior works of relational maintenance, most studies emphasize friends and intimate partners. Little research was found that portrays the maintenance of family relationships, especially the relational maintenance between adolescents and parents (Caughlin, Koerner, Schrodt, & Fitzpatrick, 2011). In addition, the intervention of new media technologies, such as the Internet, led to the various comparisons between individual relationships in online and offline environments. Most research topics are surrounded by friendship maintenance and are not extended to the scope of new technologies and relational maintenance between adolescents and parents.

Intimacy

Intimacy in general refers to the level of disclosure and mutual share of personal thinking, feeling, common interests or even imagination. As mentioned above, the phase of adolescence is when young children begin separating from their parents’ protection and control and gradually evolve to establish intimate relationships with others. Researchers have compared adolescence with other stages of human development and concluded that the relationships between adolescents and parents are full of tensions and contradictions. The adolescents may hold different opinions to their parents and are expected to generate family conflicts that deteriorate their personal relationships and intimacy at school and further expand into society (Roming & Bakken, 1992). Solomon, Warin, Lewis, and Langford (2002) hold the belief that intimate conversation between adolescents and parents is associated with family communication and benefits maintaining a good family relationship. Hu, Wood, Smith, and Westbrook (2004) revealed the connections between personal uses of instant messaging and intimate relationships, but their study was limited to exploring new relationship between

Meanwhile, Subrahmanyam and Smahel (2011) believed that individuals’ perceptions and consequences of intimacy are determined by different communicative partners. Few studies has been conducted to explore the connections between relational maintenance and level of intimacy during the intervention of new communication contexts and further attention should be given to this (Parks & Floyd, 1996).

The intimacy of interpersonal relationship is regarded as a multi-dimensional construct. Miller and Lefcount (1982) examined how social intimacy affects individuals’ relational satisfaction. Tolstedt and Stokes (1983) further divided the concept of intimacy into intimate relationships in terms of verbal, affection and physical contact. Moss and Schwebe (1993) explored the marriage relationship and pinpointed that the intimacy of loving partners exists within cognition, affection and physical contact, including both physical and psychological commitment. Considering the determinants of adolescent-parent communication and relationships, we aim to answer the following research question:

RQ1: Which new media technology is mostly used by adolescents to communicate with their parents?

RQ2: What are the factors that determine the adolescent-parent communication and relationship via new media technologies?

The relationship between adolescents and parents is genetic-bound and cannot be forced to be separated by any mean. The intervention of new media relied on the long-term and mutual interactions between both parties. Other factors associated with psychological determinants should also consider their effects respectively, such as adolescents’ gender, age, family background, communication media, and family communication patterns.

Family Communication Patterns (FCP)

Family communication is regarded as a long-term and crucial indicator in human relationship development. With the advent of TV into family life, the media uses and family relationship becomes a central subject among communication studies (Brown et al., 1999; Chaffee, McLeod, & Atkin, 1971; Lull, 1980). Acknowledging the importance of

family communication patterns toward personal relationships and media choice, Koerner and Fitzpatrick (2002) extend the concept of McLeod and Chaffee (1972) and propose two major patterns, conversation-oriented and conformity oriented. The conversation orientation describes a family scenario where every family member can freely discuss and participate in all kinds of topics, including sharing individual activities, thoughts and feelings on family occasions. In contrast, the conformity orientation emphasizes the homogeneity of each family member’s attitude, value and beliefs in a family. The principle of family communication is determined by harmony, conflict avoidance and interdependence. In traditional family contexts, children often follow the suggestions and decision making from their parents. Based on this anatomy, family communication patterns can be further categorized as consensus (i.e., high conceptual and high social) and pluralistic (i.e., high conceptual and low social), protective (i.e., low conceptual and high social) and laissez-faire (i.e., low conceptual and low social) (Koerner & Fitzpatrick, 2002). It is shown to be a reliable tool to understand and evaluate the impact of family communication on the development of personal relationships, such as psychological responses, conflict management and relational quality. Marketing researchers consider how the patterns of family communication would affect individuals’ motivations in media use and interpersonal relationships and further affect their social learning and decision making, respectively (Moore & Moschis, 1983; Moschis, 1985). Researchers attempt to evaluate the impact of family communications on other aspects, such as parent–adolescent relationships and peer relationships. Ritchie and Fitzpatrick (1990) pointed out that the communication patterns between father and mother are varied in their communication with children. Ledbetter (2009a) believed that family communication patterns directly affect adolescents’ peer relationship and level of intimacy. Barbato, Graham, and Perse (2003) believed that family communication patterns are associated with communication motives. As the subjects of family communication patterns were previously examined in western countries, Zhang (2007) believes that the effects of Confucianism and structure of Asian family should be also taken into account.

Communication reticence

Reticence is defined as individuals avoid communicating with others as a result of believing that the more they talk the more mistakes can happen. They choose to remain silent (Phillips, 1984). Researchers show that the evaluation of students’ reticence is helpful in finding students’ problems of verbal communication ability (Phillips, 1991). Past studies also revealed that they tend to use computer-mediated communication if they are shy, silent, and preferred thinking (Kelly & Keaten, 2007; Kelly, Keaten, Larsen, & West, 2004; Stritzke, Nguyen, & Durkin, 2004). The measurement of reticence, developed by (Keaten, Kelly, & Finch, 1997) includes six dimensions—anxiety, knowledge of communicative topics, time control, organization of thoughts, memory and reticence. Reticence is applied to compare the students’ differences in the use of various communication media, such as E-mail (Kelly, Duran, & Zolten, 2001), instant messaging (Kelly, Keaten, Hazel, & Williams, 2010) and collaborative learning systems (Sherblom, Withers, & Leonard, 2013). The extant research has never applied the measurement of reticence in the effects of adolescents’ communicative motives, relational maintenance and perceived intimacy toward communicating with parents.

The gender of adolescents

Males and females are shown to be biological different in using technologies and dealing with their relationships with others (Lin & Yu, 2008). Stafford and Canary (1991) concluded that gender is one of the determinants affecting the relational maintenance. Gender is also found to influence adolescents to develop intimate relationships and family cohesion (Roming & Bakken, 1992). Gender also shows different patterns in the uses of technology in terms of usage and content on the Internet Gross (2004). Furthermore, the parent’s role in the family also plays a part in influencing the children (Shin & Kang, 2016). For instance, the mother has more authority than the father in a family as they always influence the children’s behavior based on the standpoint of protection and nursing care and are more often to be rejected by her children (Golish, 2000). The dyads relationships between parents

and adolescents are also worth of further examination. Martin and Anderson (1995) explore fathers’ communication motives, self-disclosure and relational satisfaction with adolescents. Repinski and Zook (2005) revealed the level of intimacy based on children with different age groups, including adolescents. Ritchie and Fitzpatrick (1990), in their measurement of family communication patterns, also studied children with different age groups and examined the relationships based on different communicators in the family. Hence, the association of gender between adolescents and parents should be verified in detail.

The choices of communication media

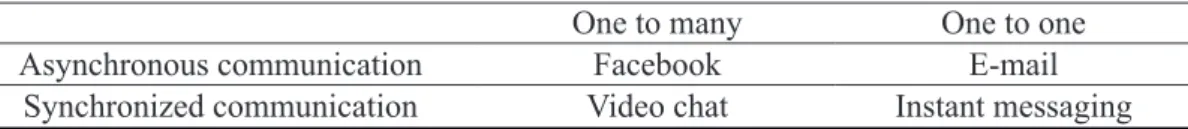

The theory of media effect can be divided into channel choice and media usage (Brandtzæg, 2010). The mix of media channels are posited to affect individuals’ media uses and their relationships (Haythornthwaite, 2005; Meng, Williams, & Shen, 2015). Compared with face-to-face communication, individuals can communicate via computer-mediated communication in different time and space, which is assumed to affect interpersonal relationships generated online and offline (Parks & Roberts, 1998; Walther, 1992; Walther & Parks, 2002). Meanwhile, the choice of communication medium should be determined by both senders and recipients (Table 1) and is regarded to affect their relational behavior and level of closeness/or intimacy (Ledbetter, Taylor, & Mazer, 2016; Ramirez & Broneck, 2009).

Table 1. The characteristics and communicator of new media technologies

One to many One to one Asynchronous communication Facebook E-mail

Synchronized communication Video chat Instant messaging

Synthesized from the literature above, this study incorporates the constructs of interpersonal communication motives and family relationships to understand the determinants that drive adolescents to interact with parents from the interventions of new communication technologies. Prior studies have verified the hypothesis that the uses of new media technologies are inclined to affect different family members, such as parents and peers (Rudi, Dworkin, Walker, & Doty, 2015). The mediated framework of interpersonal motives, relational maintenance and perceived intimacy has been verified by previous research to study the parent-adolescent relationship but it is not granted to apply to the scenario of adolescent-parent relationship without any modification (Chang, 2015). The scenarios of such communication from different communicators and media technologies have been verified from the parents’ perspectives, while it is still unknown whether the theoretical framework is still valid from the adolescents’ viewpoints.

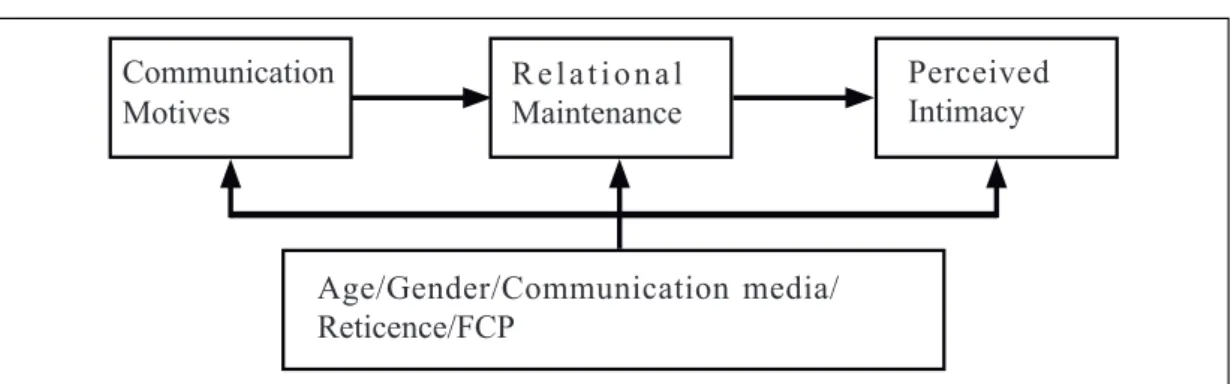

Furthermore, the adolescents’ family situation and the intervention of technologies are varied; it is also critical to take the influences of external factors into account. For instance, the wide applications of family communication patterns can be used to verify that adolescents in different family styles may be varied in their family relationships. In summary, this study applies five external factors to examine the moderation effects of adolescents’ communication motives, relational maintenance and intimacy, such as age, gender, choices of communication technology, reticence, and family communication patterns. The method of integrating mediation and moderation effects is expected to generate more solid results than relying solely on the interpretations of linear relationship (Edwards & Lambert, 2007; Hayes, 2013). The hypothesized mediation-moderation framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

This study explores the related literature associated with the uses of technology by adolescents and develops an empirical model by examining the connections among adolescents’ communication motives, relational maintenance and intimacy with their parents. Meanwhile, we also examine the external effects by family communication patterns, choice of media technology, communication reticence, and individual differences toward the adolescent–parent relationships.

Participants

‘Adolescent’ in this study is defined as teenagers aged from 12 to 18 years old with experiences in using new communication devices or applications to communicate with their parents. The survey was conducted by using the online questionnaire and convenient sampling. The process of data collection was conducted from May 20 to June 15, 2014. Comparing to the distribution of adolescent samples in a nation-wide survey, we collect samples by randomly selecting regions, age groups and school types by the helps of high school community. The respondents were randomly selected by school authority and completed the questionnaire in the computer lab. The high school teachers were trained to serve as the survey administrators and each teacher was given a $50 gift voucher in return of their assistant. After excluding samples who did not use any online applications or only face-to-face communicate with their parents, a total of 352 valid responses was collected.

Figure 1. The conceptual framework

Age/Gender/Communication media/ Reticence/FCP

Communication

Instruments

Referring to the ICTs uses in the family communication contexts by Rudi et al. (2015), the communication by adolescents was evaluated by the frequency of new media technology that he/she mostly use to communicate (i.e. every day, two to three times per week, four to five times per week, once per week, at least two to three times in two weeks, once per two weeks and at least once per month) and with specific recipient (i.e. father or mother). The questionnaire was developed by an adapted version of the interpersonal communication motives scale (Rubin et al., 1988), the relational maintenance scale (Canary & Stafford, 1992), and the intimacy scale (Hu et al., 2004). The measures were adapted so the subjects were reporting why and how they communicate with parents. The responses were solicited on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree). However, for the adolescents to comprehend the meaning of questionnaire, the original scales were translated from English to Chinese. Based on the principle of cross-culture study, this study followed the principle by Breslin (1970) and conducted back translation with the assistance of two communication scholars and one native English editor to check the comprehension of translation is equal to the original one. In addition, a pretest was performed by selecting ten high school students to verify anything unclear in the survey questionnaire. The results showed that both reliability and validity were achieved and enabled us to proceed to the next phase of data analysis (Churchill, 1979).

Procedures

Participants were asked to complete an online survey about their uses of new media technologies to communicate with their parents. After consenting to participate in this study, participants provided basic demographic information. The survey program then inquired the participants to choose from a list of new media technologies they often use to communicate with their parents. Based on the technology selected, the survey program assigned the participants to specify the parents they mostly utilize. The questionnaire was

then automatically adjusted based on the contexts participants selected above.

The online questionnaire consisted of three sections. The first section asks adolescents about the medium technology and usage frequency they use to communicate with their parents. The second section asks about adolescents’ perceptions of using new media technology, such as motivation, relational maintenance, and intimacy in comparison with face-to-face communication with parents. Other self-report psychological scales were also included, such as family communication patterns and communication reticence. The third section asks for the background information and family situation of the adolescents, such as gender, age, residence, parents’ education, and number of family members.

Results

In 352 valid samples, most adolescents use instant messaging and social networking sites to communicate with parents (87.2%). To avoid a few cases affecting the stability of statistical results, we excluded respondents who use E-mail, microblog, and VoIP phone, and 307 samples are included in the data analysis.

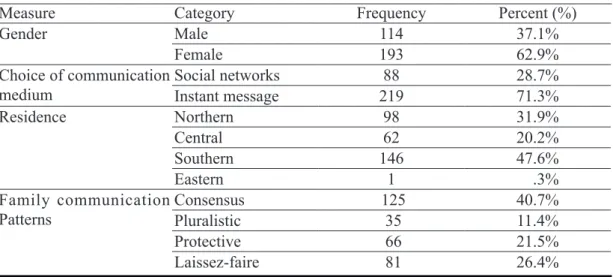

Adolescent samples were consisted of 192 females and 114 males; and most were in high school (77.9%). Apart from face-to-face communication, the majority of adolescents use instant messaging to communicate with their parents (71.3%), followed by social networking sites (28.7%). Comparing to another samples in our study, a similar proportion is shown in both parties, further inferring that both adolescents and parents may have similar preferences in their choices of communication medium. Participants were collected from southern Taiwan (47.6%), northern Taiwan (31.9%), and central Taiwan (0.2%). Due to a larger proportion of female respondents, the number of daughter–mother communication is higher than other groups (Table 2).

Model testing

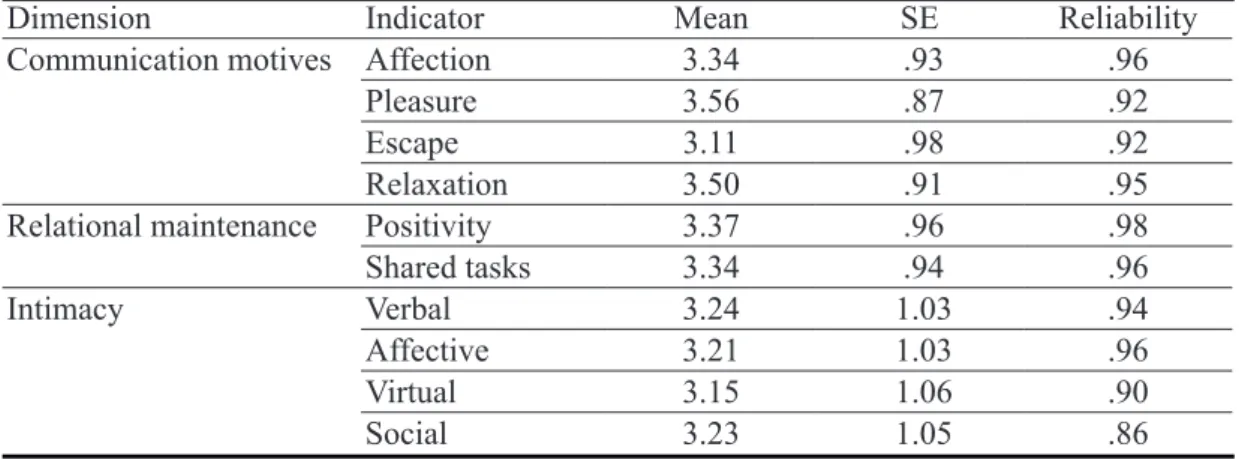

The revised 26-item interpersonal communication motives scale consists of six individual motives. Coefficient alphas for the motives in this study were .96 for affection, .92 for pleasure, .92 for escape, and .95 for relaxation. The 22-item relational maintenance scale was adapted from original measures for maintenance behavior, which consists of two dimensions. Coefficient alphas for the dimensions in this study were: .98 for positivity and .96 for shared task. The revised 14-item perceived intimacy scale consists of four dimensions. Coefficient alphas for the dimensions were: .94 for verbal, .96 for affective, .90 for virtual, and .86 for social (Table 3). The instrument is assessed for achieving the accepted threshold reliability above the value of .7 (Nunnally, 1978).

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of respondents’characteristics (N=307)

Measure Category Frequency Percent (%)

Gender Male 114 37.1%

Female 193 62.9%

Choice of communication

medium Social networksInstant message 21988 28.7%71.3%

Residence Northern 98 31.9%

Central 62 20.2%

Southern 146 47.6%

Eastern 1 .3%

Family communication

Patterns ConsensusPluralistic 125 35 40.7%11.4% Protective 66 21.5% Laissez-faire 81 26.4%

Table 3. The mean values, standard deviations and reliability of research

instruments

Dimension Indicator Mean SE Reliability Communication motives Affection 3.34 .93 .96

Pleasure 3.56 .87 .92

Escape 3.11 .98 .92

Relaxation 3.50 .91 .95 Relational maintenance Positivity 3.37 .96 .98 Shared tasks 3.34 .94 .96 Intimacy Verbal 3.24 1.03 .94 Affective 3.21 1.03 .96 Virtual 3.15 1.06 .90 Social 3.23 1.05 .86 According to the literature, the interpersonal communication motives (Barbato et al., 2003), family communication patterns (Ledbetter, 2009a), family role (Martin & Anderson, 1995), and communication reticence (Kelly et al., 2010) have resulted in their connections with adolescents’ motivation, relational maintenance strategies, and perceived intimacy. Unlike other studies which attribute the factors of family communication patterns, family role and communication reticence to be the determinants of adolescents’ attitude and behavior, we use them as moderators to verify their effects to the model indirectly.

There are two approaches to verify the existence of moderators. The first one is to verify the interaction effects between moderators and independent indicators (Baron & Kenny, 1986). Another approach is to reveal the group differences, such as a Sobel Test (Hayes, 2009; Sobel, 1982) to assess the effects of moderation. Considering the characteristics of family communication patterns, family role and communication reticence are treated as categorical variables, this study applies the second approach to verify the moderation effect.

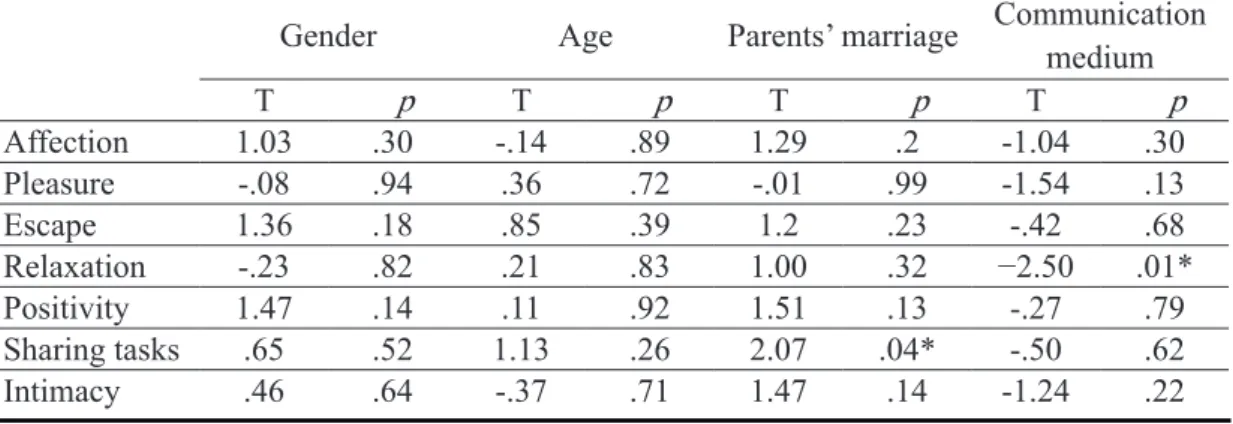

This study took adolescents’ demographics, choices of communication medium, parents’ marriage, and family roles in a group comparison with their communication motives, relational maintenance and perceived intimacy in communication with parents. The results show that adolescents would use different communication media to chat with parents when

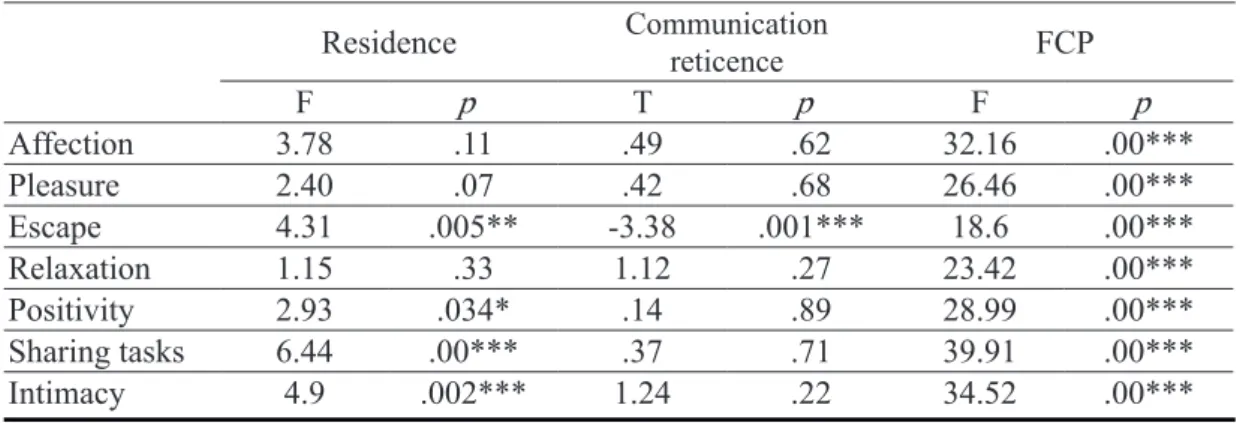

To identify the effect of individual situations, we use one-way ANOVA to verify effects of individual groups among adolescents’ communication motivations, relational maintenance and intimacy in the communication with parents (Table 5).

effects on adolescents’ sharing motivation. This result might be worth noting as adolescents who live with their parents are more willing to share interesting information with parents via new communication media. In contrast, new communication media may have limitations in bridging the communication gap for adolescents with divorced parents. Gender and age did not show significant effect on adolescents’ motivation, relational maintenance and perceived intimacy (Table 4).

Table 4. The cross-analysis between adolescents' information and psychological

factors

Gender Age Parents’ marriage Communication medium

T p T p T p T p Affection 1.03 .30 -.14 .89 1.29 .2 -1.04 .30 Pleasure -.08 .94 .36 .72 -.01 .99 -1.54 .13 Escape 1.36 .18 .85 .39 1.2 .23 -.42 .68 Relaxation -.23 .82 .21 .83 1.00 .32 −2.50 .01* Positivity 1.47 .14 .11 .92 1.51 .13 -.27 .79 Sharing tasks .65 .52 1.13 .26 2.07 .04* -.50 .62 Intimacy .46 .64 -.37 .71 1.47 .14 -1.24 .22 *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

The above results show that adolescents’ residences have significant influence on adolescents’ communication motivation, relational maintenance, and intimacy. A further analysis was conducted using the method of Scheffe to locate the differences. The adolescents in southern Taiwan may have a stronger escape motivation, hold a positive and mutual sharing attitude and higher level of intimacy to communicate with parents than adolescents residing in other regions. This result may contradict the general opinion that adolescents in northern Taiwan live in a higher density of metropolitan area where people frequently use new communication technologies to talk with each other. A possible explanation is that adolescents in southern Taiwan are more adapted to use new communication channels to interact with parents. The school adolescents attend is more far away and this requires more opportunities for family contact when they are traveling back and forth from school and home. Further evidence is required to provide insights for this result. In addition, adolescents’ family communication patterns show significant effects when comparing adolescents’ perceptions with communicating with parents via new communication media. The results show adolescents from consensus families have stronger motivations, relational maintenance and intimacy to use new media tools in communicating with parents. In contrast, adolescents from protective families only show significant differences in the expression of their intimacy with parents.

Table 5. The cross-comparison between external indicators and psychological

factors

Residence Communication reticence FCP

F p T p F p Affection 3.78 .11 .49 .62 32.16 .00*** Pleasure 2.40 .07 .42 .68 26.46 .00*** Escape 4.31 .005** -3.38 .001*** 18.6 .00*** Relaxation 1.15 .33 1.12 .27 23.42 .00*** Positivity 2.93 .034* .14 .89 28.99 .00*** Sharing tasks 6.44 .00*** .37 .71 39.91 .00*** Intimacy 4.9 .002*** 1.24 .22 34.52 .00***

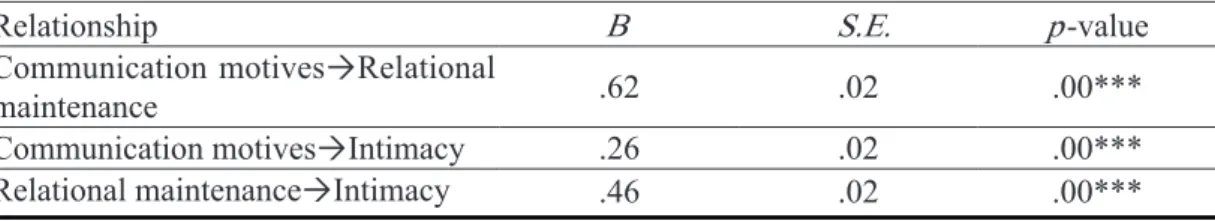

To test the hypothesis that adolescents’ motivation and relational maintenance influences the subsequent level of intimacy, we conduct regression analysis to examine the model fitness and the strength of relationship among variables. After four rounds of model testing, the model explained 69.47% of the variance. The result can be described in the following formula.

Intimacy = (.35) (Affection) + (-.24) (Pleasure) + (-.03)(Escape) + (.11)(Relaxation) + (.29)(Positivity) + (.42) (sharing tasks)

We also conducted path analysis to examine the direct and indirect effects among communication motivations, relational maintenance and intimacy (Table 6). The results show their relationships are positive. The relational maintenance plays a mediating role between communication motivations and perceived intimacy and is attributed to be partial mediated based on the comparison of unstandardized regression weights and statistical significance (Figure. 2).

Table 6. The results of path analysis

Relationship B S.E. p-value Communication motivesRelational

maintenance .62 .02 .00***

Communication motivesIntimacy .26 .02 .00*** Relational maintenanceIntimacy .46 .02 .00*** *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Figure 2. Path coefficients of model testing

Comm.

Motives PerceivedIntimacy Relational Maintenance R2=56.2% R2=69.3% .46*** .26*** .62***

According to the results of the regression analysis, the reason for young people to use new communication technologies to communicate with their parents were mainly derived from affection, pleasure, positivity and sharing tasks. Overall, adolescents perceive affection to be the strongest motivation that they communicate with parents. The sharing of emoticon and funny moments could be the activities that adolescents want to share with parents when they are in a joyful mood. Regarding their status of relational maintenance, adolescents believe that sharing tasks and positive assurances can help them to maintain strong ties wherein they are assisted by the new communication media, which further complements the level of intimate relationships with parents.

Conclusion

Adolescents are increasing their usage on sending messages and images as a way to connect with friends and family members daily, especially in Chinese family (Huang & Leung, 2010). Evidence shows that more adolescents have attempted to chat with parents through instant messaging than social networking sites. Hence, new communication technology is certainly an issue that adolescents can exploit when communicating with parents instead of attributing to technology addictions. Some adolescents consider using new technologies to report their daily routine as convenient (Kornblum, 2011) while others reject their parents as the disclosure of personal privacy online(Shin & Kang, 2016). This

study shows that the affection and relaxation are the motivations that drive adolescents to communicate with parents by means of new communication technologies. Adolescents may also regard positive assurance and task sharing as their strategy to consolidate their relationships and intimacy with parents. The results have broken through the limitation of prior research within the study of the same peer group (e.g., loving partners or friends) or implications from a single result from communication (e.g., relational satisfaction or closeness) and reveal the dynamic structure of communication between adolescents and parents. In contrast to face-to-face communication, both adolescents and parents should have an open mind to discuss or share information online with each other, which also reflects the assumptions by Solomon et al. (2002). They argue that parents used to direct the access to media use in the family. However, the emergence of new communication technology not only equalizes the power structure between adolescents and parents, but also create an open space for encouraging self-disclosure and emotional sharing in the family.

The effects of family communication patterns have been regarded as determinants that directly formulate the adolescents’ relationships. In contrast to the mediator approach by Ledbetter (2014), this study took a different approach by categorizing adolescents with different family communication patterns and observing the changes in their communication motives, relational strategies and perceived intimacy, correspondingly. Compared to the study of Chinese family communication patterns by Zhang (2007), this study also shows the family communication patterns in adolescents’ communication strategies with parents has shifted from conformity to consensus. The best communication strategy for a consensus family is collaboration rather than escape. For a pluralistic family, it is suitable for competition rather than collaboration. The communication motives, relational maintenance and intimacy between adolescent and parent in the use of new communication technologies are varied and thus each type of family should adjust their communication strategy to improve the level of intimacy in their relationships.

The communication between adolescents and parents is worth more attention as more technology tools are pervasive in our daily life. Little research has been found that explicitly

discusses the impact of communication technologies on family relationships (Rudi, Walkner, & Dworkin, 2014). Some studies specified the intervention of certain mediums, such as social media (Kanter, Afifi, & Robbins, 2012), Internet (Williams & Merten, 2011) and the comparisons of different media (Lundy & Drouin, 2016), to evaluate the intervention of computer-mediated communication toward family relationships. This study compared the adolescents’ use of two communication technologies—instant messaging and social networking sites—in communication with parents and concludes that the preferences and uses of specific communication medium may have a moderate impact on the interaction process and consequences of adolescent–parent relationship. The attempt of comparing various interpersonal communication media also extends prior assumptions of media effect as most studies were pertained to the effects of specific communication media (Ledbetter et al., 2016). The effects of media modality, as rooted in the Media Multiplexity Theory (MMT), are evaluated based on the cognitive process and can be linked to the interventions of adolescent-parent relationship.

The stage of adolescence is critical to the development of interpersonal relationships and social cognition. The finding of this study may provide useful guidelines for social workers and parents to provide appropriate assistants with healthy communication and solid relationships. For instance, results from our prior study on parents (Chang, 2015) also show parents and adolescents can have the feel of sharing and instant response through new communication tools may mitigate the tension of parent-adolescent relationships, such as communications through online chatting, photo sharing, and check-in from Facebook. In addition, the benefits of resolving family tasks through online communication, such as arranging daily activities by mobile applications or through instant messaging, can strength family bonds and more adapted to the daily routine. The emphasis of family communication patterns also provides a good reference for adolescents to pertain better strategy and family relationship with parents through online communication. The guidelines of parenting programs or consulting services can be refined based on the family communication patterns

Appendix

References

Ajzen, I., & Madden, T. J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social

Psychology, 22(5), 453-474.

Altman, I., & Taylor, D. A. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal

relationships. New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Barbato, C. A., Graham, E. E., & Perse, E. M. (2003). Communicating in the family: An examination of the relationship of family communication climate and interpersonal communication motives. Journal of Family Communication, 3(3), 123-148.

Barbato, C. A., & Perse, E. M. (1992). Interpersonal communication motives and the life position of elders. Communication Research, 19(4), 516-531.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182.

Blackshaw, P. (2009, November 2). A Pocket Guide to Social Media and Kids. Nielsen. Retrieved from http://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/news/2009/a-pocket-guide-to-social-media-and-kids.html

Boase, J., Horrigan, J. B., Wellman, B., & Rainie, L. (2006). The strength of Internet ties. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2006/PIP_Internet_ ties.pdf.pdf

Brandtzæg, P. B. (2010). Towards a unified Media-User Typology (MUT): A meta-analysis and review of the research literature on media-user typologies. Computers in Human

Behavior, 26, 940-956.

Breslin, R. W. (1970). Back translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of

Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 185-216.

Brown, J. D., Childers, K. W., Bauman, K. E., & Koch, G. G. (1999). The influence of new media and family structure on young adolescents' television and radio use.

Communication Research, 17(1), 65-82.

Canary, D. J., & Stafford, L. (1992). Relational maintenance strategies and equity in marriage. Communication Monographs, 59, 243-267.

Canary, D. J., Stafford, L., Hause, K. S., & Wallace, L. A. (1993). An inductive analysis of relational maintenance strategies: Comparisons among lovers, relatives, friends, and others. Communication Research Reports, 10(1), 3-14. doi:10.1080/08824099309359913

Carvalho, J., Francisco, R., & Relvas, A. P. (2015). Family functioning and information and communication technologies: How do they relate? A literature review. Computers in

Human Behavior, 45, 99-108.

Caughlin, J. P., Koerner, A. F., Schrodt, P., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2011). Interpersonal communication in family relationships. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.), The SAGE

handbook of interpersonal communication (pp. 679-714). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chaffee, S. H., McLeod, J. M., & Atkin, C. K. (1971). Parental influences on adolescent media use. American Behavioral Scientist, 14(3), 323-340.

Chang, P.-C. (2015). The examination of parent-adolescent communication motives, relational maintenance and intimacy in the uses of communication technologies.

Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 7(10), 171-181.

Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs.

Journal of Marketing Research, 16, 64-73.

Dindia, K., & Canary, D. J. (1993). Definitions and theoretical perspectives on maintaining relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10, 163-173.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256-273.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological

Methods, 12(1), 1-22.

turning point analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31(2), 170-178.

Graham, E. E., Barbato, C. A., & Perse, E. M. (1993). The interpersonal communication motives model. Communication Quarterly, 41(2), 172-186.

Gross, E. F. (2004). Adolescent Internet use: What we expect, what teens report. Journal of

Applied Developmental Psychology, 25(6), 633-649.

Gunuc, S., & Dogan, A. (2013). The relationships between Turkish adolescents’ Internet addiction, their perceived social support and family activities. Computers in Human

Behavior, 29(6), 2197-2207.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Journal of Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408-420.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process

analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Haythornthwaite, C. (2005). Social networks and Internet connectivity effects. Information,

Communication & Society, 8(2), 125-147.

Hu, Y., Wood, J. F., Smith, V., & Westbrook, N. (2004). Friendships through IM: Examining the relationship between instant messaging and intimacy. Journal of

Computer-Mediated Communication, 10(1), Article 6.

Huang, C.-K., Li, C.-T., & Wang, M.-F. (2014). Investigation on digital cultural feedback and obstacles in intergenerational family. Kaohsiung Normal University Journal:

Education and Social Sciences, 37, 51-72.

Huang, H., & Leung, L. (2010). Instant messaging addiction among teenagers: Abstracting from the Chinese experience. In J. B. (Ed.), Addiction Medicine (pp. 677-686). New York, NY: Springer.

Kanter, M., Afifi, T., & Robbins, S. (2012). The impact of parents "friending" their young adult child on Facebook on perceptions of parental privacy invasions and parent-child relationship quality. Journal of Communication, 62(5), 900-917.

Kelly, L., Duran, R. L., & Zolten, J. J. (2001). The effect of reticence on college students' use of electronic mail to communicate with faculty. Communication Education, 50(2), 170-176.

Kelly, L., & Keaten, J. A. (2007). Development of the affect for communication channel scale. Journal of Communication, 57, 349-365.

Kelly, L., Keaten, J. A., Hazel, M., & Williams, J. A. (2010). Effects of reticence, affect for communication channels, and self-perceived competence on usage of instant messaging. Communication Research Reports, 27(2), 131-142.

Kelly, L., Keaten, J. A., Larsen, J., & West, C. (2004). The impact of reticence on use of

computer-mediated communication II: A qualitative study. Paper presented at the

annual convention of the National Communication Association, Miami Beach, ML. Koerner, A. F., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (2002). Toward a theory of family communication.

Communication Theory, 12(1), 70-91.

Kornblum, W. (2011). Sociology in a changing world (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., & Crawford, A. (2002).

Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58(1), 49-74.

Ledbetter, A. M. (2008). Media use and relational closeness in long-term friendships: Interpreting patterns of multimodality. New Media & Society, 10, 547-564.

Ledbetter, A. M. (2009a). Family communication patterns and relational maintenance behavior: Direct and mediated associations with friendship closeness. Human

Communication Research, 35, 130-147.

Ledbetter, A. M. (2009b). Patterns of media use and multiplexity: associations with sex, geographic distance and friendship interdependence. New Media & Society, 11(7), 1187-1208.

Ledbetter, A. M. (2014). A theoretical comparison of relational maintenance and closeness as mediators of family communication patterns in parent-child relationships. Journal

of Family Communication, 14(3), 230-252.

frequency and determines its relational outcomes: Toward a synthesis of uses and gratifications theory and media multiplexity theory. Computers in Human Behavior,

54(1), 149-157.

Lee, S. J. (2009). Online communication and adolescent social ties: Who benefits more from Internet use? Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 4(3), 509-531. Lenhart, A., Lewis, O., & Rainie, L. (2006). Teenage life online: The rise of the instant

message generation and the Internet's impact on friendships and family relationships. In K. M. Galvin & P. J. Cooper (Eds.), Making connections: Readings in relational

communication (pp. 355-362). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lenhart, A., Madden, M., Macgill, A. R., & Smith, A. (2005). Teens and technology: Youth

are leading the transition to a fully wired and mobile nation. Washington, DC: Pew

Internet & American Life Project.

Lin, C.-H., & Yu, S.-F. (2008). Adolescent Internet usage in Taiwan: Exploring gender differences. Adolescence, 43(170), 317-331.

Lull, J. (1980). Family communication patterns and the social uses of television.

Communication Research, 7(3), 319-333.

Lundy, B. L., & Drouin, M. (2016). From social anxiety to interpersonal connectedness: Relationship building within face-to-face, phone and instant messaging mediums.

Computers in Human Behavior, 54(3), 271-277.

Macgill, A. (2007). Parent and teen Internet use. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet. org/2007/10/24/parent-and-teen-internet-use/

Madden, M., Lenhart, A., Duggan, M., Cortesi, S., & Gasser, U. (2013). Teens and

Technology 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Research. Center Retrieved from http://www.

pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2013/PIP_TeensandTechnology2013.pdf. Martin, M. M., & Anderson, C. M. (1995). The father-young adult relationship:

Interpersonal motives, self-disclosure, and satisfaction. Communication Quarterly,

Interpersonal motives, self-disclosure, and satisfaction. Communication Quarterly,

43(2), 119-130.

McLeod, J. M., & Chaffee, S. H. (1972). The construction of social reality. In J. Tedeschi (Ed.), The social influence processes. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

Meng, J., Williams, D., & Shen, C. (2015). Channels matter: Multimodal connectedness, types of co-players and social capital for multiplayer online battle arena gamers.

Computers in Human Behavior, 52(4), 190-199.

Mesch, G., & Talmud, I. (2006). The quality of online and offline relationships: The role of multiplexity and duration of social relationships. The Information Society: An

International Journal, 22(3), 137-148.

Mesch, G. S. (2003). The family and the Internet: The Israeli case. Social Science Quarterly,

84(4), 1038-1050.

Miller, R. S., & Lefcount, H. M. (1982). The assessment of social intimacy. Journal of

Personality Assessment, 46, 514-518.

Moore, R. L., & Moschis, G. P. (1983). Role of mass media and the family in development of consumption norms. Journalism Quarterly, 60(1), 67-73.

Moschis, G. P. (1985). The role of family communication in consumer socialization of children and adolescents. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(4), 898-913.

Moss, B. F., & Schwebe, A. I. (1993). Marriage and romantic relationship: Defining intimacy in romantic relationships. Family Relation, 42, 31-37.

Myers, S. A., Brann, M., & Rittenour, C. E. (2008). Interpersonal communication motives as a predictor of early and middle adulthood siblings' use of relational maintenance behaviors. Communication Research Reports, 25(2), 155-167.

Nie, N. H., Hillygus, D. S., & Erbring, L. (2002). Internet use, interpersonal relations, and sociability: A time diary study. In B. Wellman & C. Haythornthwaite (Eds.), The

Internet in everyday life (pp. 215-243). Malden: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2 ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

functioning. In F. Walsh (Ed.), Normal family processes (2nd ed., pp. 104-137). New York: Guilford Press.

Parks, M. R., & Floyd, K. (1996). Meanings for closeness and intimacy in friendship.

Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 13(1), 85-107.

Parks, M. R., & Roberts, L. D. (1998). 'Making Moosic': The development of personal relationships on line and a comparison to their off-line counterparts. Journal of Social

and Personal Relationships, 15(4), 517-537.

Phillips, G. M. (1984). Reticence: A perspective on social withdrawal. In J. A. Daly & J. C. McCroskey (Eds.), Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication

apprehension (pp. 51-66). Beverly Hills: Sage.

Phillips, G. M. (1991). Communication incompetencies: A theory of training oral

performance behavior. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Ramirez, A., & Broneck, K. (2009). 'IM me': Instant messaging as relational maintenance and everyday communication. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(2-3), 291-314.

Repinski, D. J., & Zook, J. M. (2005). Three measures of closeness in adolescents' relationships with parents and friends: Variations and developmental significant.

Personal Relationships, 12(1), 79-102.

Ritchie, L. D., & Fitzpatrick, M. A. (1990). Family communication patterns: Measuring intrapersonal perceptions of interpersonal relationships. Communication Research,

17(4), 523-544.

Riva, G. (2002). The sociocognitive psychology of computer-mediated communication: The present and future of technology-based interactions. CyberPsychology & Behavior,

5(6), 581-598.

Roming, C., & Bakken, L. (1992). Intimacy development in middle adolescence: Its relationship to gender and family cohesion and adaptability. Journal of Youth and

interpersonal communication motives. Human Communication Research, 14(4), 602-628.

Rudi, J. H., Dworkin, J., Walker, S., & Doty, J. (2015). Parents' use of information and communications technology for family communication: Differences by age of children. Information, Communication & Society, 18(1), 78-93.

Rudi, J. H., Walkner, A., & Dworkin, J. (2014). Adolescent-parent communication in a digital world: Differences by family communication patterns. Youth & Society, 47(6), 811-828.

Schrodt, P., Ledbetter, A. M., Jernberg, K. A., Larson, L., Brown, N., & Glonek, K. (2009). Family communication patterns as mediators of communication competence in the parent-child relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(6-7), 853-874.

Schutz, W. C. (1966). The interpersonal underworld. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

Schwartz, J. (2004). That parent-child conversation is becoming instant and online. The

New York Times. Retrieved from

http://www.nytimes.com/2004/01/03/business/that-parent-child-conversation-is-becoming-instant-and-online.html

Sherblom, J. C., Withers, L. A., & Leonard, L. G. (2013). The influence of computer-mediated communication (CMC) competence on computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) in online classroom discussions. Human Communication, 16(1), 31-39.

Shin, W., & Kang, H. (2016). Adolescents' privacy concerns and information disclosure online: The role of parents and the Internet. Computers in Human Behavior, 54(1), 114-123.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290-312). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

and their teenage children: Democratic openness or covert control? Sociology, 36(4), 965-983.

Stafford, L., & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships,

8(2), 217-242.

Stritzke, W. G. K., Nguyen, A., & Durkin, K. (2004). Shyness and computer-mediated communication: A self-presentational theory perspective. Media Psychology, 6, 1-22. Su, A.-L. (2011). The behavior and attitude regarding the use of interactive media among

adolescents in great Taipei area: A survey study. Unpublished master's thesis , National

Taiwan Normal University, Taipei.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Greenfield, P. (2008). Online communication and adolescent relationships. The Future of Children, 18(1), 119-146.

Subrahmanyam, K., & Smahel, D. (2011). Intimacy and the Internet: Relationships with

friends, romantic partners, and family members. New York, NY: Springer.

Tapscott, D. (2009). Grown up digital: How the net generation is changing your world. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill

Thorton, A., Orbuch, T. L., & Axinn, W. G. (1995). Parent-child relationships during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Family Issues, 16(5), 538-564.

Tolstedt, B. E., & Stokes, J. P. (1983). Relation of verbal, affective, and physical intimacy to marital satisfaction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 30(4), 573-580.

Vogl-Bauer, S., Kalbfleisch, P. J., & Beatty, M. J. (1999). Perceived equity, satisfaction, and relational maintenance strategies in parent-adolescent dyads. Journal of Youth and

Adolescence, 28(1), 27-49.

Vuchinich, S., Ozretich, R. A., Pratt, C. C., & Kneedler, B. (2002). Problem-solving communication in foster families and birthfamilies. Child Welfare, 81(4), 571-594. Walther, J. B. (1992). Interpersonal effects in computer-mediated interaction: A relational

hyperpersonal interaction. Communication Research, 23, 3-43.

Walther, J. B., & Parks, M. R. (2002). Cues filtered out, cues filtered on: Computer-mediated communication and relationships. In M. L. Knapp & J. A. Daly (Eds.),

Handbook of interpersonal communication (pp. 529-536). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Williams, A. L., & Merten, M. J. (2011). iFamily: Internet and social media technology in the family context. Family & Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 40(2), 150-170. Zhang, Q. (2007). Family communication patterns and conflicts styles in Chinese