中文摘要 本研究為期三年,主要目的是提昇科學教師的促進科學理解教學與評量知能,以促進學 生科學學習。第一年的研究目的是(1)形成理解的理論,發展相契合之教學模式或策略 與評量方法;(2)收集學生相關迷思概念的類別與成因以為課程設計的參考。(3)建立教 學目標、教學設計、評量標準。第二年研究主要目的是應用第一年的成果,(1)培訓參 與教師進行促進科學理解教學與評量課程設計;(2)現場測試新課程,收集教師教學與 學生理解資料與證據,修正教學模式與課程後,再次進行教學修訂課程。第三年研究主 要目的是(1)探討促進理解教學與評量模式之教學成效;(2)探討參與教師教學改變與專 業成長;(3)分享與推廣促進理解教學與評量模式。研究期間進行促進科學理解相關文 獻探討,收集參與研究老師相關文件資料、會議資料、訪談記錄與教學錄影,以準實驗 研究設計探討促進理解教學與評量模式之教學成效,並進行效度及信度考驗及分析、整 合。研究重要成果包括:建立「促進科學理解教學與評量模式」;在課程成效部分,實 驗組學生在認知、態度、思考智能、科學探究、後設認知等向度統計顯著優於一般教學; 參與教師在課程設計能力、學習理解的再建構、科學知識、教學省思等面向都有改變; 至於推廣成效部分,由完成設計之四十份教案中發現教師能展現教學創意進行教案設 計,大多數老師的教案具備評量取向的課程設計特色,且涵蓋至少三個理解的面向。 關鍵詞:科學理解、教學模式、教學成效

Abstract

The purposes of this three-year study were to promote teachers’curriculum design ability and practices to improve students’understanding of science. In the first year the researcher (1) formulated theory of understanding, teaching model, and assessment,(2) collected students’ misconceptions on specific topics, (3)built standards on teaching purpose, learning experience, and assessment. Based on the result of first year, the researcher (1) cooperated with participant teachers to design curriculum for science understanding, (2) tried the new curriculum in school context and made modification in the second year. The purposes of the third year were to (1) investigate the effect of the new curriculum, (2) explored the changes of participant teachers, (3) share the teachig model for understanding with other science teachers. The researcher reviewed literature, collected data on teachers’practices during the study. The effect of the new curriculum was tested through quasi-experimental design. Reliability and validity were checked. The “Teaching for Understanding Model”was constructed. There were significant differences between students’performance of experimental group and control group on cognition, attitude, thinking sill, science inquiry, and metacognition. Through the curriculum designing process, the participant teachers changed and enhanced their curriculum designing ability, meaning of understanding, science knowledge, and reflective thinking. The results of spread course showed that 40 teachers extended their idea of teaching for

the Advancement of Science)出版的資料科學素養的里程碑(Benchmarks for Science Literacy)則提到知道、體認、鑑賞、熟悉、辨識、獲取等多種類似的動詞。 表面的或他人的意見與深入、檢證過的想法是不同的,正確答案不足以證明理解, 好的考試成績也可能有迷思概念存在。我們要如何區辨學生真正理解與只是表面的、機 械式的、與情境無關的記憶或想法? 日常用語中理解有多種的意涵,理解具不同層次、深度,可以不同表現及結果呈現 理解的程度。例如:深入的理解,表面的理解,粗淺的理解,理解是需要時間及練習, 是發展的過展的過程,不易獲得,不易立即理解,不是全有全無,而是有不同層次,如: 生手與專家,簡單到複雜,理解不只有知識本身,更有檢証的能力,及情境條件,如若…… 則,……否則…….。 除了理解以外,教育學者也常用「頓悟」、「知慧」。視理解為動詞狀態,則具有教 學的個人間的及知能的意義。例如如果你會教、會用、會証明、會解釋、辯護、領悟字 裡行間的意義,那麼你真正理解。而表現評量中:學生必需表現,應用知識以証明其真 正理解,但理解亦可能以其他型式出現:例如以有趣的角度說明事物即是一種應用不同 觀點呈現複雜概念的具體表現。

我們常說:我快要理解了,改變心意、改變想法。Oxford English Dictionary 對 “understand”的定義是:體會想法的意義及重要性。無論如何,理解不同於質樸,無 經驗。有時為了理解,需有段距離,站在別人的角度設想,例如性別議題,代溝的問題, 文化衝繁。

Perkins 在 Teaching for Understanding 這本書中(Wiske, 1998)定義「理解」 是思考的能力、彈性的應對……與機械式記憶不同(P.40)。其舉出理解的架構是:知 識、方法、目的、形式,訂定理解的四個層次:素樸學習者、初學者、學徒、熟練者。

Anderson & Krathwohl(2001)則針對 Bloom 教育目標的分類修訂,提出學習、教學 與評量的分類。文中對理解的定義是由教學訊息中建構意義,並以以不同形式詮釋 (interpreting)、典型範例說明(Exampligying)、分類(classfying)、整合或形成一 般性(summarizing)、推論(inferring)、比較(comparing)、以模型解釋(explaining) 七個面向。

義的部分;它們很難經由教導而改變 (尤其以傳統,教誨的教學方法) ; 它們在世界各 地的教室經常以類似的頻率出現。在許多情況下,先存概念深植在個人的概念生態中, 以至於互相矛盾的資訊不是被反駁,就是被修改以符合先前存在的理論(Driver 及 Oldham,1986)。概念改變是廢除根深蒂固信念的認知劇變(Fisher, Wandersee & Moody, 200)。

Wandersee , Mintzes 和 Novak(1994)回顧 3000 個以上的科學迷思概念研究,他 們指出迷思概念的八個特色。這些特色在下面詳細說明。 1.學習者帶著一套與自然的物體和事件不同的另有概念來到正式科學課程。通常有 20%或者更多學生持有這些另有概念,大部份的科學教師對學生的心智中的這些想法並 不瞭解。 2.學習者的另有概念是超越年紀,能力,性別和文化的界線。 許多類似概念在其 他學生和在全世界一般人身上都找得到的。 3.通常前一代的科學家和哲學家對自然現象解釋提出類似的另有概念。這些超越空 間和時間廣泛存在的質樸概念是人類敏感性的結果。人們是從有限的資料中獲得的邏輯 結論,他們強調許多科學想法是與日常情理相違背的觀點。 4.另有概念源自個人不同的經驗中,包括直接觀察和理解,同儕的文化和語言,以 及教師的解釋和教學的內容中都有它們的起源。他們是感官組合的結果。 5.在一般教學策略的情境下,另有概念是頑強地抵抗改變或消失。在概念性的衝擊 突下,學生通常需要令人信服的證據以改變其概念。只是簡單的告訴他們不足以去除他 們根深蒂固的信仰系統。學生擁有的想法非常穩固,且能滿足他們的需要,科學思想相 當勉強的代替原有想法,或科學思想與學生原有想法二者並存於學生的認知結構中。科 學思想被拒絕的可能原因是他們是陌生的,愚蠢的或者難以相信的;也可能由於感情因 素,學生固執自己的思想,不願改變。在其他情況中,科學思想可能被改變或者誤譯, 以能與學生的思想一致。 6.教師通常與他們的學生具有相同的另有概念。如同在上面指出的,另位概念不局 限於學生,他們對人類就如同呼吸一樣的自然,我們全部都有。它們存在是因為多數人, 包括科學家,在他們的每天生活中並不是使用科學方法去瞭解世界。此外,多數人對每 個領域累積的知識了解有限,人僅僅在他們有限的知識基礎上推衍出最好的結論。 7.學習者的先前知識和在正式教學中呈現的知識相互作用,導致一套多樣化非預期 的學習結果。許多教師認為「我告訴了他們,他們聽到了我說的,所以他們知道了」, 事實上, 這可能是教育上最普遍的迷思概念。 8. 需要一套有效的概念改變教學方法以促進迷思概念的改變。然而這樣的教學方 法通常很難去發現而且執行起來相當耗時。通常有效的概念改變策略是以探究的科學教 學和建構主義的學習理念為核心。 總之,先存概念對個人或者群體不是獨特的,它們是超越過年紀,性別,和文化, 他們在科學的歷史中有規律地出現,而且他們在許多成年人的認知架構中也會出現。先 前概念是個體試圖以有限的知識合理的瞭解其所在的世界。學生進入教室之前,一直持 續地瞭解他們周遭的世界,有用的先前概念大量存在學生的認知結構中。學習者的先存 概念不但是個人知識建構的一個合理的結果,也是建構學習理論的有力驗証(Von Glasersfeld, 1987;Fisher,1991;Gunstone , 1994)。 國內迷思概念研究,過有許多重要的研究發現(例如熊召弟民 84;),近年在郭重吉 校長領導之下為期四年之國科會整合型概念研究研究,針對迷思概念的類別、評測工 具、起源等都有跨越不同學科、年級的豐盛結果其結果發表於 2003 數學與科學的對話; 概念學習研討會(民 92)、數學與科學學習國際研討會(International Conference on Science & Mathematics Learning, 2003)及相關學術刊物。

認真學習的學生也不理解時,則是教師應好好的反省教學目標及教學及評量方法的時候 了。 三、促進理解的教學與評量 促進理解並非一蹴可及,必需投入相當的時間、精力、反思、努力、挑戰,因為他 和人日常生活經驗及想法有很大的不同。理解也似乎沒有結果的時候,他不斷的深入、 添加、新意,當我們經歷不同的經驗與他人討論、反思。 現代學習觀認為有效的教學法必須考慮學生舊有建構的知識,光是講授傳達教學不 是有效的教學方法,因為傳達的科學知識很可能與學生持有的知識互相衝突。學生接受 講授傳達式的教學,很可能以他先前建構的錯誤知識為基礎解釋新教的知識,因此老師 想要傳授給他們的知識,未必相當於他們所獲得的知識,那麼在教學上要增進學生對科 學概念的學習,教師需要持有什麼教學上的認知呢? 科學教育研究的歷史在 1987 年後進入人本建構主義時期,主要的認識論是後實證 主義/建構主義,強調意義的建構、理解能力、概念改變、知識的結構與品質。代表人 物如 Novak,Vygotsky,Kuhn,Toulmin,Glasersfeld,其中 Novak 的人本建構主義 (Mintzes & Wandersee,1998)提出三個基本主張:

1. 人類是意義的形成者。

2. 教育的目標是為建構共同的意義。

3. 共同的意義可經由準備完全的老師之主動教學介入而促成。

基於此一理念,Mintzes & Wandersee(1998)指出目前對於概念改變的重要觀點之 一是強調概念改變的過程。從建構主義的觀點來看概念改變,強調學習者必須先了解自 己的概念,進而評估這些概念,而後決定是否要重建這些概念,一旦決定重建,則須重 檢視並重整其原有概念的相關看法,使其達到一致性。不論是教師、班上其他同學,以 及教室內的教學結構,最後都會影響學生的理解、評估以及決定是否重新重整與檢視個 人概念的理解過程(Gunstone & Mitchell,1998)。基於此假設,研究者建議教師可使 用許多不同的教學策略以促進學生理解,例如圖形組織體、後設認知、科學史哲(概念 的歷史發展)、類比教學、電腦及相關科技、多元媒體、小組分享、互動式歷史小故事, 促進學生的說與做科學,建議教師應扮演如同催化劑的角色啟動及加速概念的改變,以 促進意義化的學習(Mintzes & Wandersee, 1998)。並建議教師廣泛應用概念圖、V 形圖、 訪談、教室對話、觀察、檔案評量、電腦軟體、寫作、筆記等協助及評量學生理解情形 (Mintzes,Wandersee & Novak,1999)。

哈佛大學一群學者所進行之「促進理解之教學方案」(Wiske,1998)在這方面著力 甚著,他們以理解四向度:知識、方法、目的、形式為依歸,發展了一套教學模式並考 驗之。他們以跨學科的主題進行教學,強調:清楚的教學目標、豐富的學習經驗、表現 評量。研究群建議教師扮演學習者,教師所設計之課程需能引發學生的學習興趣,並與 學生磋商建構知識。研究群收集學生的理解證據,並提出一套培育職前與在職教師的模 式,非常的完整,是教師及師資培育者重要參考依據。 Gallagher 博士及其在密西根大學的同事發展另一套能有效協助教師進行促進理解 及應用的教學模式,稱為 Mercede 模式,以知識-理解-應用三個面向說明之,並提供 不同的教學策略以促進科學的理解與應用。此模式建議教師多使用促進理解的教學策 略,包括:概念圖、寫作、小組活動、閱讀理解、寫日誌、圖形或模式表徵、解釋圖形、 小組形成解釋、分析小組工作、延伸性提問,發展學生應用能力部分則建議交多尋求日 常生活中應用、以報紙為可能來源、寫下可能應用、以圖或模型表徵應用、小組進行應 用、問對的問題、應用性問題。教學時並搭配循環性的形成性評量(Collins, Brown & Newman, 1989)。這項課程設計在學習環境及概念理解及外在考試成績中亦都有成效 (Gallagher, 2000)。

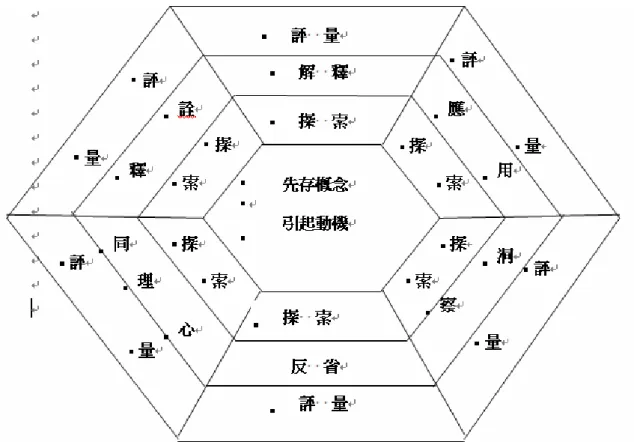

心生不滿,才進而引導概念改變的發生。又提出,一個新概念欲進入原有架構中,將會 發生以下兩種可能情形:第一種情形是被拒絕,第二種情形則以三種可能方式合併進 來:(1)依背誦方式記憶;(2)取代舊有概念,並藉著概念轉變過程與剩餘的概念調 和;(3)以概念捕獲的過程與原概念調合併存。一般而言,必須在上述的概念轉變條 件下透過學習者轉化或同化與調適的學習過程,才較有可能產生概念的轉變。 Hewson,Beeth 及 Thorley(1998)繼而根據學生的學習奠基於個人建構與社會建構主義 為相輔相成的理念下,提出概念改變教學的指引:(1)討論與說明學生與教師的想法(2) 後設認知:可用與前測比對、討論與比較、質疑學生的想法鼓勵學生監控自己的認知過 程(3)確定想法所處的狀態:是否有用?合理?有效?(4)想法與決策的驗證,四個循環 過程。其中前二者屬於個人內在的權威(internal authority),師生都要有充分的機會 明白的說明他們的想法並進行批判式的檢驗。驗證屬於外在權威(external authority),可以是學術權威、課程權威或文化權威等不同的形式。想法的狀態則為內 在權威與外在權威間的橋樑,提供進行比較與選擇的機會。教師必須幫助學生與其他的 同學或教師於各種不同的權威間做整合。這意謂教師需在課程、教學策略、教室交互作 用、評量形式上做改變。而學生的角色也有巨大的不同,如,為自己的學習負起責任、 更主動。課程則不僅注重事實與概念性的科學知識,更強調知識獲得的過程與驗證程序。 Wiggins & Mctighe(1998)依其理解六面向進行課程設計,強調重要概念、廣度與 深度、深入培養,在六面向分別建議: 面向 1. 建立、考驗、檢証理論或解釋,建議此問題為基礎的學習引發。可用對談、 交互作用、表現實作評量,發掘學生迷思概念的方法,使用生手一專家連續性的規準, 設計引發重要理論之問題的課程及評測。 面向 2. 詮釋:口述歷史、文獻分析、個案研究,對談式專題討論。 面向 3. 真的或模擬工作 面向 4. 研讀指述同一事件的不同文件。評量學生:它是什麼?是夠及完備性,情 境合宜,採用批判性觀點。 面向 5. 宜接經驗及角色辦演模擬過去事件及可能的態度。 面向 6. 自評及自我修正。 其教學模式稱為”WHERE”,即起點(where)→引起動機(Hook)→探究(Explore) →反思(Reflect)→評鑑(Evaluate)。認為教科書只是教學資源、參考之一,課程的 編排以螺旋課程為主提出課程設計評判標準。期望教師少教一些,而學生能多學一些, 並依教學目標在說教師及教練式教學策略中融入建構式教學策略,並府以形成性及表現 評量做法: 另外還有一些知名的模式如: 1. 學習環(Learning cycle):Lawson(1988)提出探究、名詞界定、應用的循環三 階段在美國頗為風行。後有學者 Glass(1993)以融合社會建構的理念重現修訂學 習環,指出語言在建構概念、澄清、磋商時的重要性,並強調三階段間螺旋、交互 特性。

2. Generative learning model:投入與探索學生的想法、釐清、挑戰、應用 (Cosgrove & Osbornl,1985)

3. Interactive Approach:準備、探究、學生的問題、學生的探究、反思 (Biddulph,1990)

4. Science in School Research project:(Tyler, R. 2002):投入、挑戰與生 活或興趣相連、學生學習需求或喜好、嶔入式評量、不同方式呈現科學特性。 綜觀上述教學的基本要素包括:

(2)建構主義取向學習環境量表

第五章

結果與討論

第一年成果

一、科學理解的理論 Bloom(1956)在其教育目標的分類一書中提到「理解」,但定義卻不是非常明確, 例如「真正理解」「內在化的知識」,「了解其真正核心意義」指的是相同的意思嗎?理 解事實,考試得高分算是理解嗎?Bloom 及其同事(1956)指出理解並非知識的累積。 而機械式的記憶與理解的不同,Bloom(1956)指出真正的知識包括遷移,即在新的情 境中應用知識。他們認為知能與記憶性的知識是不同的。AAAS(American Association for the Advancement of Science)出版的資料科學素養的里程碑(Benchmarks for Science Literacy)則提到知道、體認、鑑賞、熟悉、辨識、獲取等多種類似的動詞。 表面的或他人的意見與深入、檢證過的想法是不同的,正確答案不足以證明理解, 好的考試成績也可能有迷思概念存在。我們要如何區辨學生真正理解與只是表面的、機 械式的、與情境無關的記憶或想法? 日常用語中理解有多種的意涵,理解具不同層次、深度,可以不同表現及結果呈現 理解的程度。例如:深入的理解,表面的理解,粗淺的理解,理解是需要時間及練習, 是發展的過展的過程,不易獲得,不易立即理解,不是全有全無,而是有不同層次,如: 生手與專家,簡單到複雜,理解不只有知識本身,更有檢證的能力,及情境條件,如若… 則,…否則…。 除了理解以外,教育學者也常用「頓悟」、「知慧」。視理解為動詞狀態,則具有教 學的個人間的及知能的意義。例如如果你會教、會用、會証明、會解釋、辯護、領悟字 裡行間的意義,那麼你真正理解。而表現評量中:學生必需表現,應用知識以証明其真 正理解,但理解亦可能以其他型式出現:例如以有趣的角度說明事物即是一種應用不同 觀點呈現複雜概念的具體表現。我們常說:我快要理解了,改變心意、改變想法。Oxford English Dictionary 對 “understand”的定義是:體會想法的意義及重要性。無論如何,理解不同於質樸,無 經驗。有時為了理解,需有段距離,站在別人的角度設想,例如性別議題,代溝的問題, 文化衝擊。

Perkins 在 Teaching for Understanding 這本書中(Wiske,1998)定義「理解」 是思考的能力、彈性的應對…與機械式記憶不同(P.40)。其舉出理解的架構是:知識、 方法、目的、形式,訂定理解的四個層次:素樸學習者、初學者、學徒、熟練者。

Anderson 及 Krathwohl(2001)則針對 Bloom 教育目標的分類修訂,提出學習、教學 與評量的分類。文中對理解的定義是由教學訊息中建構意義,並以不同形式詮釋

理解的評量需選用適當的評量方式,並顧及理解的各層面,收集理解的證據,需 考慮評量與課程的銜接度、密合度,以及理解的層次、評判規準,以發展觀點,進行 具有信度、效度的評量,詳細流程如圖 5-2。附錄十四是以植物單元為例,所進行的教 學設計示例。

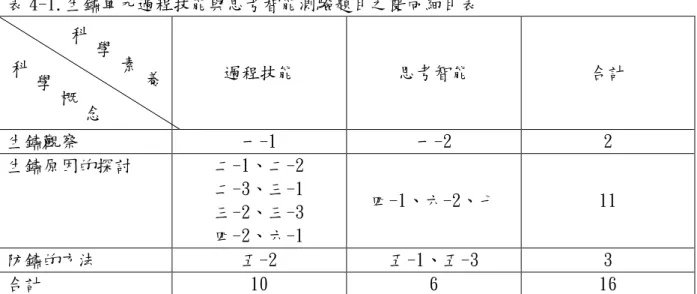

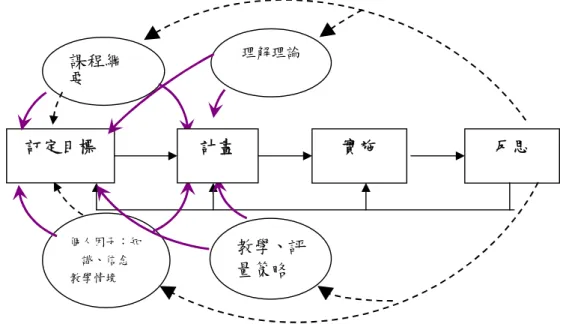

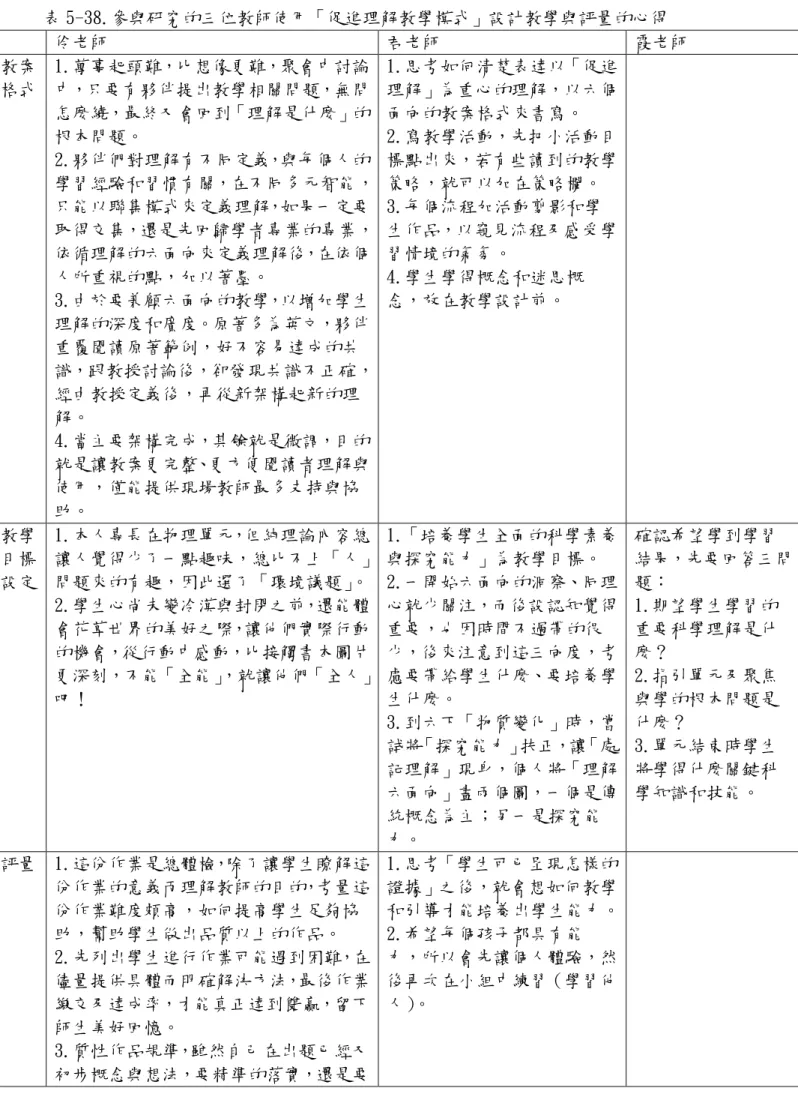

訂定目標 C.促進使用新知識的策略 D.促進教學策略的策略 E.促進反思的策略 大寫〝X〞表示主要目的,小寫〝x〞表次要目的 參與研究之國小自然科教師,組成研究團隊,將就課程、教學方式、學生學習情況、 學習理解情形進行教學策略的反思與批判。而教師專業成長模式如圖 5-4 所示。

圖 5-4.教師專業發展模式(改編自 Loucks-Horsley,Hewson,Love & Sitles,1998)

(四)兩組學生在「科學學習態度」表現上的差異情形 1.生鏽探究活動的態度量表 (1)測驗結果 由表 5-26 中可看出,實驗組在對生鏽探究活動的態度量表之後測平均數比對照組 高,且實驗組的後測分數比前測高,而對照組學生後測平均數低於前測平均數。是否達 顯著差異,則需進行共變數分析。 表 5-26.兩組學生在「對生鏽探究活動的態度量表」之前後測得分之平均數與標準差摘 要表 對生鏽探究活動的態度量表前測 對生鏽探究活動的態度量表後測 組別 平均數 標準差 平均數 標準差 實驗組 2.9304 .2862 3.1574 .5659 對照組 2.9538 .4463 2.8803 .5500 (2)組內迴歸係數同質性考驗 由表 5-27 發現 F 質未達顯著(F=0.896,P=0.348>.05),表示實驗組與對照組的迴歸 係數相同,符合組內迴歸係數同質性假定,繼續進行共變數分析。 表5-27.兩組學生在「對生鏽探究活動的態度量表」之組內迴歸係數同質性考驗摘要表 變異來源 SS df MS F Sig. 組間 .267 1 .267 .896 .348 誤差 16.968 57 .298 (3)單因子共變數分析 由表 5-28 可知,F 值達顯著(F=4.184,P=.045),顯示經實驗處理後,兩組學生在 對生鏽探究活動的態度表現上有差異,且達統計上的顯著水準(P<.05)。表示接受促進理 解教學設計教學的實驗組在對生鏽探究活動的態度表現優於一般教學的對照組。由表 5-28 可知其 η2值為 0.67,經計算後求得 f 值為 0.27,根據 Cohen 之論述,其效果量為中到 高效果,顯示促進理解教學設計教學對於生鏽探究活動的態度的提升具有中到高的效果。 表 5-28.兩組學生在「對生鏽探究活動的態度量表」共變數分析摘要表

參考文獻

中文部分 國科會科教處(民 92),2003 數學與科學的對話:概念學習研討會會議手冊,高雄:高 雄師範大學。 王靜如(民 89),系統化改變國小自然科教學之研究。屏東師院學報,第 13 期,頁 281-316。 李暉、郭重吉(民 89),科學對話與科學概念之學習:以國中理化課學習為例。科學教 育,第 10 期,3-30 頁。 林達森(民 90),合作學習與認知風格對科學學習之效應。教育學刊,第 17 期,頁 255-279。 林曉雯(民 90),國小自然科教師試行「學習環」教學策略之行動研究。國立屏東師範 學院學報,第十四期,頁 953-986。 林曉雯(民 92a),學生對「開花植物生長發育」概念之瞭解。師大學報:科學教育類, 第四十八卷,第一期,頁 45-60。 林曉雯(民 92b),植物生長發育概念之研究:教科書與教學對五年級學生學習的影響。 2003 數學與科學的對話:概念學習研討會會議手冊,頁 45-46。高雄:高雄師 範大學。 邱美虹(民 89),概念改變研究的省思與啟示。科學教育學刊,第 8 卷,13 期,頁 1-34。 黃台珠、陳昱宏(民 89),從社會建構的觀點看一個高中生物教室的合作學習。科學與 教育學報,第 4 期,頁 21-60。 陳忠志(民 87),國中教師科學本質及科學教學信念對理化教室環境的影響。科學教育 學刊,第 6 卷,第 4 期,頁 383-402。 張美玉(民 87),建構取向的科學教室內師生互動實例。科學教育學刊,第 6 卷,第 2 期,頁 149-168。 教育部(民 87),國民教育階段九年一貫課程總綱綱要。教育部。 郭金美(民 88),建構主義教學方法-影響學生光學概念學習教學模式的研究。嘉義師 院學報,第 13 期,頁 157-201。 郭重吉(民 77):從認知的觀點探討自然科學的學習。國立台灣教育學院學報,第 13 期,頁 351~397。 許榮富、黃芳裕(民 84):當今科學概念發展研究賦予科學學習的新意義。科學教育月 刊,第 178 期,頁 2-13。 國科會科教處(2003):數學與科學學習國際研討會(International Conference on Science & Mathematics Learning),台北。熊召弟 (民 84):學童的生物觀。台北:心理出版社。

英文部分

Anderson, L.W. & Krathwohl, D.R.(Eds.)(2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing. New York: Addision Wesley Longman.

Bloom, B.S.(Ed.)(1956). The taxonomy of Educational objectives, The classification of educational goals, Handbook I: Cognitive domain. New York: David Mckay. Biddulph, F. (1990). Pupil questioning as a teaching/learning strategy in primary science

education. In B. Bell(1993), Children’s science, constructivism and learning in science. Geelong: Deakin University.

Brickhouse,N.W.(1990).Teacher’sbeliefsaboutthenatureofscienceand theirrelationship to classroom practice. Journal of Teacher Education, 41(3), 53-62.

Chiu, M.H.(2001),Algorithmic Problem Solving and Conceptual Understanding of Chemistry by Students at a Local High School in Taiwan. Proceedings of the National

Science Council(Part D.), 11(1), 20-38.

Collins, A., Brown, J., & Newman, S.(1989). Cognitive apprenticeship: Teaching crafts of reading, writing, and mathematics. In L. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing, learning, and instruction: Essays in honor of Robert Glasser. Hillsdale NJ: Erlbaum.

Cosgrove, M. & Osbornl, R. (1985). Lesson frameworks for changing children’s ideas. In R. Osborne and P. Freyberg (Eds.), Learning in Science: The implications of Children’s Science (pp. 101-111). Auckland: Heinemann.

Driver, R., & Oldham, V.(1986). A constructionist approach to curriculum development in science. Studies in Science Education, 13, 105-122.

Duffee, L. & Aikenhead, G.(1992) Curriculum Change, Student Evaluation, and Teacher Practical Knowledge. Science Education, 76(5), 493-506

Duit,R(1997).Diagnosing student’slearning.Paperpresented in 1997 International

Workshop on Student’sConceptDevelopment,Understanding:Diagnosis and Teaching. Taipei. Taiwan.

Duit, R. & Treagust, D. (1998). Learning in science from behaviourism towards social constructivism and beyond. In B. Fraser & K. Tobin(Eds.), International handbook of science education. Dodrecht, the Netherlands: Kluwer.

Fisher, K.M.(1991). SemNet: A tool for personal knowledge construction. In P. A. M Kommers, D. H. Jonassen & J. T. Mayes (Eds.), Cognitive tools for learning, (pp.63-75). Berlinm: Springer-Verlag.

Fisher, K.M., Wandersee, J.H. & Moody, D.(Eds.)(2000). Mapping biology knowledge. London: Kluwer.

Gallagher,J. J. (2000). Teaching for understanding. School Science and Mathematics, 100(6), 310-318.

Glass, G. (1993). Reinterpreting the learning cycle from a social constructivist perspective: A qualitative study of teachers’belief and practice. Journal of Research in Science

Teaching, 30(2), 187-207.

Glatthorn, A. A.(1987). Cooperative professional development: Peer-centered options for teacher growth. Educational Leadership, 45(3), 31-35.

Glatthron, A. A.(1990) Supervisory leadership. Glenview. Illiniois Scott Foresman. Gunstone, R. F.(1994). The importance of specific science content in the enhancement of

metacognition. In P. Fensham, R. Gunstone & R. White(Eds.), The content of science: A constructivist approach to its teaching and learning(pp.131-146). London: Falmer. Gustone, R.F. & Michell, I.J.(1998). Metacognition and conceptual change. In J.J.Mintzes,

J.H.Wandersee, & J.D. Novak(Eds.), Teaching science for understanding: A human constructivist view(pp.133-163). San Diego: Academic

Haney, J. J. & Lumpe, A. T. (1995). A teacher professional development framework guided by reform policies, teachers’needs, and research. Journal of Science Teacher Education,

6(4), 187-196.

Hewson, P. W. (1996). Teaching for conceptual change. In D. F. Treagust, R. Duit, & B. J. Fraser(Eds.), Teaching and learning in science and mathematics(pp.1331-140). New York: Teachers College Press.

Hewson, P. W. , Beeth, M.E., & Thorley, N.R.(1998). Teaching for conceptual change. In B.J.Fraser, & K.G. Tobin(Eds.), International Handbook of Science

Education(pp.199-218). Boston: Kluwer.

Huberman, M. (1989) The Professional life cycle of teachers. Teach. Coll. Rec. 91(1), 31-57. Lawson, A. E. (1989). A theory of instruction: Using the learning cycle to teach science

concepts and thinking skills. NARST Monograph, Number One,Arizona.

Lin, S. W.(2003a, Mar.). Students’understanding of flowering plants growth and development: An interview study. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of National Association for Research in Science Teaching. PA. Philadelphia.

Lin, S.W.(2003b, Dec.). Development and application of a two-tier diagnostic test to assess high school students’understanding of flowering plant growth and development. Paper presented at the International Conference on Science & Mathematics Learning,Taiwan: Taipei.

Loucks-Horsley,S., Hewson,P.W., Love, N. & Sitles, K.E. (1998). Designing professional development for teachers of science and mathematics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. McLaughlin, M. W,.& Tallert, J. E. (1990). The contexts in question: The secondary school

workplace. In:M. W. McLaughlin, J. E. Tallert, & N. Bascia (Eds.), The Contexts of

Teaching in Secondary Schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Mintzes, J.J. & Wandersee, J.H. (1998). Reform and innovation in science teaching: A human constructivist view: A human constructivist view. In J.J.Mintzes, J.H.Wandersee, & J.D. Novak(Eds.), Teaching science for understanding: A human constructivist

view(pp.30-58). San Diego: Academic.

Mintzes, J.J. & Wandersee, J.H. (1998). Research in science teaching and learning: A human constructivist view. In J.J.Mintzes, J.H.Wandersee, & J.D. Novak(Eds.), Teaching science for understanding: A human constructivist view(pp.59-92). San Diego: Academic.

Mintzes, J.J., Wandersee, J.H. & Novak, J.D.(Eds.) (1999). Assessing science understanding: A human constructivist view. San Diego: Academic.

Nationsl Commission on Excellence in Eduction. (1983). A nation at risk: The imperative for educational reform. Washington DC: US Department of Education.

Richardson, V. & Halmilton, G. (1994). From behaviorism to constructivism in teacher education. Teacher Education and Special Education, 19(3), 263-71.

Russell, T.(2002). Teaching for understanding in science. Australian Science Teachers

Journal, 48(4), 30-35.

Treagust, D. F., Jacobowitz, R., Gallagher, J. L. & Parker, J.(2001). Using assessment as a guide in teaching for understanding: A case study of a middle school science class learning about sound. Science Education, 85(2), 137-57.

Tobin, K. (1990). Changing metaphors and beliefs: A master switch for teaching? Theory into

Practice, 29(2), 122-127.

Tobin, K., & Gallagher, J., (1987). What happens in high school science classrooms? Journal

of Curriculum Studies, 19 (6), 549-560.

Von Glasersfeld, E.(1987). Learning as a constructive activity. In C. Janvier (Ed.), Problems of representation in the teaching and learning of mathematics(pp. 215-227), Hillsdale, NJ.: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wallace,J.& Louden,W.(1992)Scienceteaching and teachers’knowledge: Prospects for reform of elementary classrooms. Science Education, 76(5), 507-521.

Wandersee, J. H., Mintzes, J. J., & Novak, J. D.(1994). Research on alternative conceptions in science. In D. L. Gabel(Ed.), Handbook of research on science teaching and learning. New York: Macmillan.

Wiggins, G. & Mctighe, J.(1998). Understanding by design. Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wiske, M.S.(Ed.).(1998). Teaching for understanding. Linking research with practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

3. 小英設計了另一個實驗來驗證他們的想法-「莖能夠蒸散水分」,她的實驗設計如下 圖:

實驗裝置好後,小英應該觀察什麼變化呢?

六小時後實驗裝置變成這個樣子:

參、決定理解的證據〈步驟2〉

出席國際學術會議心得報告

計畫編號 95-2511-S-153-002-計畫名稱 促進理解之科學教學與評量(3/3) 出國人員姓名 服務機關及職稱 林曉雯 國立屏東教育大學數理教育研究所 會議時間地點 2006 年 11 月 28-30 日 香港教育學院 會議名稱 亞太教育研究會國際研討會 2006 教育領導與專業發展;

學校教育改革的管理;

教育市場化與私營化;

職業技術教育改革;

教育研究與政策及實踐的聯繫。

大會安排了幾場專題演講,圍繞著今年的主題,相當紮實。例如大會主席 Yin Cheong Cheng 教授 以:Future Developments of Educational Research in the Asia-Pacific Region – Reforms, Paradigm Shifts and Networks 為題,闡述本會主要議題,尤其是以知識為基礎 的教育創新、政策發展以及實務改進等。緣此,凸顯教育研究在此轉變世代中的重要性,尤 其是資培育與教師專業成長的重要議題。主張無論地方、區域的或國家層級的教育改革,漸 漸都需與世界其他區域的教育研究形成綿密的網路,以促進教育品質的提昇,迎接未來世界 的挑戰。

澳洲的 Colin Power 教授以「Educational Research, Policy and Practice in an Era of Globalisation」為題,強調面對全球化的變遷,開放市場、通訊科技、政策與研究創新 是最有效的利基。教育研究不可避免需面對此一變遷,需探究最急迫、優先的教育研究議題, 例如,如果認為促進教育政策的改革、計畫、管理、課程、教學與評量是現今需優先研究的 主題,則教育研究經費需大力揖注,且需以研究知識為導向進行相關改變,儘量縮小政策、 研究、實務間的鴻溝。因此,如何結合各類專家學者,共同合作、分享與創造新的知識便顯 的極為重要。

紐西蘭學者 Dr. Jane Gilbert 以「Knowledge, the Disciplines, and Learning in the Digital Age 」為題,倡議學校中面臨數位時代,運用資訊科技的教學,演講中分析學校使 用資訊科技時所面臨的問題、如何有效使用,以協助教學與學習的進行。

新加坡學者 Oon-Seng Tan 以「Problem-based Learning Pedagogies:

Learning to become a Mentor

A Case Study of a Group of Science Teachers

Sheau-Wen Lin

*, Tsui-Hua Tai

**linshewen@mail.npue.edu.tw

*Graduate Institute of Mathematics and Science Education, National Pingtung

University of Education, Taiwan ROC

**

Raey Guang Elementary School, Pingtung, Taiwan ROC

Asia-Pacific Education Research Association Conference 2006

28 –30 November 2006

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to describe three elementary science mentor teachers’mentoring process and their own development during a year-long professional development intervention in the form of a mentor teacher study group directed toward fostering educative mentoring for student teachers. The collaborative action research was utilized to involve the mentor teachers to inquiry their mentoring. The database consisted of field notes of weekly meetings, interviews on mentor teacher, and copies of mentorand studentteachers’written works on mentoring. Triangulation was conducted to enhance the validity. During the mentoring, the mentor teachers interviewed student teachers to know their background and experience for planning mentorship, provided observation schedules forstudentteachersto observementors’science teaching, discussed student teachers’science lesson plans, and observed student teachers’science lessons and gave feedback. The mentor teachers reported that serving as mentors enhanced their collaboration with other members of this study group and added new instructional strategies to their teaching repertoires. The mentor teachers reflected and discussed on both their science instruction and mentoring that were beneficial to mentors, student teachers, and their students. This study contributed to the research on educating student teachers to become real practitioners and on the mentor teachers’ development.

Keywords: Collaborative Action Research, Professional Development, Mentoring for Science

Learning to be Mentor for Student Teacher in Science: A Collaborative Action Research INTRODUCTION

Mentor teachers play a central role in the development of student teachers (Hawkey, 1977). Mentoring can not only have an effect on the development of the student teacher but can have an effecton thementor’sdevelopment(Elliott,1995;Hawkey,1997).Mentorscan build a knowledge base about how to work effectively with the student teachers (Kerka, 1998). After watching the student teachers implemented research-based repertoire of teaching strategies and seeing the response of their own students to these methods, mentors may try out some of the methods themselves (Elliott, 1995).

If there is not a well-developed mentoring, the development of student teachers and mentor teachers may be problematic. In our country, student teachers had a period of school-based experience prior to receiving their teaching certificate. However, there is little role for the university supervisor or, even less of a role for the new, research-based ideas that the student teachers might want to use. Many student teachers found themselves learning-on-the-job with a narrow repertoire of teaching strategies and even less experience in making the connection between theory and practice through reflection (Lin, 2005).

The science education department in our college applied a new program and mandated a change in elementary teacher education. Student teachers must work with mentor teachers and be supervised by university faculty. Mentor teachers assess the needs of their student teachers and develop a plan for sharing their expertise based on these needs. Theses needs often relate to helping those student teachers to inquiry science instruction with setting up experiments, sharing lesson plans, and giving feedback on performance for inquiry science. Mentors are encouraged to promote their reflection regarding the effectiveness of science instruction and mentoring. Obviously, this new model requires a different role for the mentor teachers and this model was not the way these mentor teachers themselves have been educated to become teachers. The purpose of this mentoring program is to leverage the investment made in these mentor teachers by supporting their efforts to share the knowledge and skill they have gained with students teachers in their schools. In this paper, we are focusing on the description and explanation ofthesementorteachers’mentoring processand their own development.

DESIGN Collaborative Action Research

The collaborative action research was utilized to involve the mentor teachers to inquiry their mentoring. The steps included the ongoing practice of the teachers and defining problems, the actions to solve the problems, changes in practice, and new actions resulting from participation in the collaborative group. The collaborative action research allowed participant teachers and

researchers to learn more about their practices and providing a forum in which to try new strategies, receive feedback, and reflect on what was learned in the process.

Collecting and Analysis Data

mentoring. By comparing the above data sources, field notes of weekly meetings were important because mentor teachers were able to express their concerns and successes in working with the student teachers. In combination with the meeting notes, interviews, related documents, and result from survey provided a reliability check for the findings.

FINDINGS

For convenience in the discussion, the overall research process was divided into five chronological phases.

Preparing Phase

The participant school was located in a rural area about twenty minutes east of the university. It consisted of about 1500 somewhat homogenous middle-class students. The school provided an extended 5-week field experience and a 10-week student science teaching experience for interns. The four teachers taught science at this elementary school were invited to conduct this research after being contacted by the university researcher. All of the participants involved had a variety of questions and concerns on mentoring for student teachers. The university researcher's major role in this group was to provide new trends of teacher education, theory of teacher learning and

development, literature on mentoring, and some support for the teachers in this group both as a source of ideas and suggestions during the study. Tai familiar with the action research process and the mentoring process from prior studies acted as a consultant in this study. Lin, Liu, and Din had taught science for 6 to ten years and had mentoring experience for student teachers for at least three years in their school. All the members agreed that the major purpose of this group was to make a more effective science mentoring in the school in the initial meeting in September of 2004.

The group meetings were scheduled every week throughout the study. During group meetings, participants could make plans, asked and answered questions, discussed problems, and expressed reflections. The group setting was conductive to the generation of new ideas, strategies, and techniques used to initiate actions, direct the research, solve problems, and ultimately achieve the purpose of this group. Through the process, the mentor teachers adjusted their practice through reflectively informed changes in their behavior.

Baseline Data andDDeeffiinneeddpprroobblleemmss

Baseline data answers the question, “What is the current situation in regard to science mentoring for student teachers in the school?”The participants gathered information on what was currently being implemented, what plans were already in place, as well as the feelings of participant teachers and administrators toward the science mentoring for student teachers. This information constituted our baseline data and would be used for comparative reflection at the end of the cycle. The following were problems they defined from the baseline data:

Involvement: Student teachers were not fully involved in science internship.

Communication: Did not create a good communication channel between mentor and student teachers.

Student teachers teaching quality: The problems identified included managing class time, running out of materials or activities before the end of class, misconception of science, and setting up, managing and assessing science investigation.

descriptive,and specificfeedback on studentteacher’sperformance.

Planning

During the weekly meetings, the participants reviewed related literature on mentoring. Some of the information included: research findings of mentor and student teachers, professional standard of science teaching, and mentoring for student teacher. After reviewing others work, the mentor teachers spent lots of time to figure out the possible strategies for the problems they defined in the first phase, for example,

Increasing involvement: Clarity of purpose and sequencing the student teaching experiences.

Promoting communication: Creating a connection, promoting communication strategies and skills, and increasing understanding and mutual respect.

Improving studentteachersteaching quality:Discussing thestudentteacher’s

preparation in advance of the lesson for checking the understanding of student teachers and pointing out the potential problems before they happened.

Assessmentand feedback on studentteacher’sperformance:Collecting dataon observation, giving feedback in the post observation meeting, and encouraging novices to reflect on their teaching in the mentor-mentee interaction diary.

Intervention strategies/Baseline data

In intervention Actions, mentor teachers set aside time for a short private interview to get to know their student teachers at their first meeting. They also centered on discussing specific goals and objectivesaboutthenovice’sperformance.The mentors sequenced the student teaching experiences. They provided student teachers with lesson plans, books, and other materials so the novices could begin to become familiar with the science curriculum and invited student teachers to observe the mentors' classes. The student teachers were required to complete a set of written activities based on observation and discussions with the mentor teachers.

For minimize the harmful effects on pupils and monitoring the quality of student teachers teaching, mentors asked the mentees to plan detailed lesson before teaching and reviewed it carefully. All the mentors believed planning gave the beginner the needed structure to design a lesson, ensuring that no essential parts have been overlook. Some mentees did not meet the requirement. The reasons were that the planning and reviewing were time-consuming and that elementary teachers would not develop detailed plan in real teaching practice. Not surprising, maintaining learning environment became difficult and their students messed around in thestudentteacher’sclass.

During the classroom observation, the mentor teachers recorded patterns of teaching and learning, analyzing data to identify teaching strengths and growth areas. The mentor teachers held meetings to enable the student teachers to reflect on the teaching performance based on the classroom observation.

their student teachers. Mentors were willing to share ideas freely and they were able to adopt some of mentees’ideas as well. The student teachers asked many questions, took time to observe

mentor’sscienceclass, and borrowed resources from mentors that they could learn from. The student teachers also reported that the mentoring is beneficial to them, saying it helped them to grow professionally, develop a clearer idea of science teaching.

Reflections and planning for next cycle

Reflection began in March of 2005 and provided a summary of the situation at the end of the cycle. The experience had been a positive one for mentor teachers. For example,

”Afterserving asamentor,Ireturned to my classroom with arenewed attitude.Working with the mentees helped me to reflect on what I did as a teacher and why. This reflection led to better ideas to learning and teaching for my students.”

”In mentoring studentteachers,Ihavelearned thatIhaveeffectiveteaching skillsand Ican share them to help student teachers and that I need to be open to new ways of teaching in order to keep my own teaching fresh. I am happy to attend the group that I can learn from other mentors to share positive though, skills, and ideas on science teaching and mentoring that are valuableresources.”

Some of the reflections on future science mentoring on student teachers followed:

”We mentors always do not develop detailed plans. Rather we plan and record activities in a “shorthand fashion”.Theseplanning processes become embedded and the concrete reminders are no longer necessary. To assist novices, especially to those student teachers who do not understand the importance of planning for novices, we might demonstrate how to plan and prepare for the lesson, plan a lesson with mentees together, or review a lesson the beginner has already developed. This interaction processes make we mentors to check the understanding of a lesson and more important give the interns the benefit of seeing an experienced teacher move from plan to implementation. ”

”Both mentors and mentees played equally important roles in making mentee’steaching experience productive and meaningful. The challenge for both novice teachers and their mentor was to work as a team, managing differing viewpoints and building on shared perspectives. As mentoring various interns, we confront the values and beliefs of a diverse group of young adults. We know that an effective mentor know that people skills are very important skills in the

mentoring process. Next cycle, we need to increase understanding and mutual respect and acknowledge the needs and feelings of mentees. ”