College of Management

I-Shou University

Master Thesis

Open Innovation, Reverse Knowledge

Sharing and SME performance

Advisor: Dr. Julia Lin

Co-Advisor: Dr. Fu-Sheng Tsai

Graduate Student: Tang Due Au

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE i

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the constant support of two my advisors Professor Julia

Lin at the Department of International Business, I-Shou University and Associate Professor

Fu-Sheng Tsai at Department of Business Administration, Cheng-Shiu University. I am very

grateful to not only their academic contribution to my Thesis paper but also their

encouragement to allow me to pursue this Master topic.

My sincere thanks also go to Professor Shang-Pao Yeh and Assistant Professor Paula

Tomsett for serving as my committee members and helping me to better fulfill my study due

to their brilliant comments and insightful suggestions.

I also would like to express my deepest appreciation to all the company managers who

participated and completed my questionnaire survey. My thanks are extended to my friends

whose contributions help me go through the research process.

Finally and most importantly, the love from my family allows me to go throughout the

entire processes and gives me inspiration to finish this turning point of my life. From the

bottom of my heart, this Thesis is dedicated to my darling mother, Tran Thi Kim Chuan for

understanding me, going out with me, waiting up for me every night, laughing with me and

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE ii

Abstract

Open Innovation (OI) has been studied mainly in large-scaled high-tech firms or Multinational Corporations. Few have studied OI on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Since SMEs make vital contributions to national and global economics and innovations, their engagement in the OI should not be neglected. In addition, the demand to access supporting resources, especially knowledge, from open communities is critical for SMEs, through a backward knowledge flowing process called reverse knowledge sharing. This study investigates on the relationship among OI, reverse knowledge sharing and SME performance with questionnaire data collected from SMEs in Vietnam. Results indicated that there was a positive relationship between OI and reverse knowledge sharing. Results also indicated that the degree of relationship between SMEs and their stakeholders moderated the relationship between OI and reverse knowledge sharing. Practical implications and theoretical potential for future research are discussed.

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE iii

Contents

Acknowledgements ... i

Abstract ... ii

List of Tables ... v

List of Figures ... vi

List of Abbreviations ... vii

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1 Research Background ... 1

1.2 Research Significance ... 5

1.3 Problem Statement and Research Objectives ... 10

Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 11

2.1 Open Innovation ... 11

2.1.1 Open Innovation Model ... 11

2.1.2 Dimensions of Open Innovation ... 14

2.1.3 Open Innovation in SMEs ... 18

2.2 Reverse Knowledge Sharing ... 19

2.2.1 Reverse Knowledge Sharing ... 19

2.2.2 Reverse Knowledge Sharing in SMEs ... 20

2.3 Hypothesis Development ... 22

2.3.1 The Effects of Open Innovation in SMEs ... 22

2.3.3 Relationship as an Enabler of both Open Innovation and Reverse Knowledge Sharing ... 25

2.3.4 Reverse knowledge sharing as an Enabler of both Open Innovation and SME performance ... 28

Chapter 3 METHODOLOGY ... 29

3.1 Research Design ... 29 3.2 Framework ... 30 3.3 Sampling Design ... 30 3.4 Data Collection ... 33 3.5 Measures ... 34 3.5.1 Open Innovation ... 343.5.2 Reverse knowledge sharing ... 35

3.5.3 Relationship ... 38

3.5.4 SME performance ... 38

3.5.5 Control variables ... 38

3.6 Data Analysis ... 40

Chapter 4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ... 41

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE iv

4.2 Validity and Reliability Analysis ... 42

4.2.1 Validity Analysis... 42

4.2.2 Reliability Analysis ... 44

4.3 Correlation and regression Analysis ... 44

4.4 Discussion ... 47

5.1 Research summary ... 49

5.2 Theoretical and practical implications ... 49

5.3 Research limitations and Future research ... 51

Appendix A Questionnaire Cover Letter in English ... 61

Appendix B Questionnaire in English ... 62

Appendix C Questionnaire Cover Letter in Vietnam ... 66

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE v

List of Tables

Table 1.1 Top-ten barriers ranked by SMEs………... 03Table 1.2 Number of enterprises by size of enterprise.………... 04

Table 1.3 Open Innovation in Small and Medium-sized enterprises………... 07

Table 1.4 Overall score of some ASEAN countries for Access to External supports…….. 09

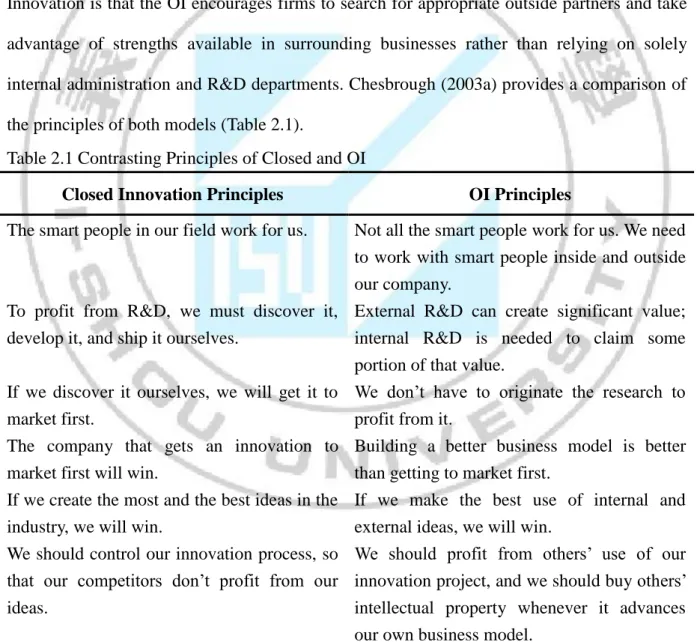

Table 2.1 Contrasting Principles of Closed and Open Innovation………... 13

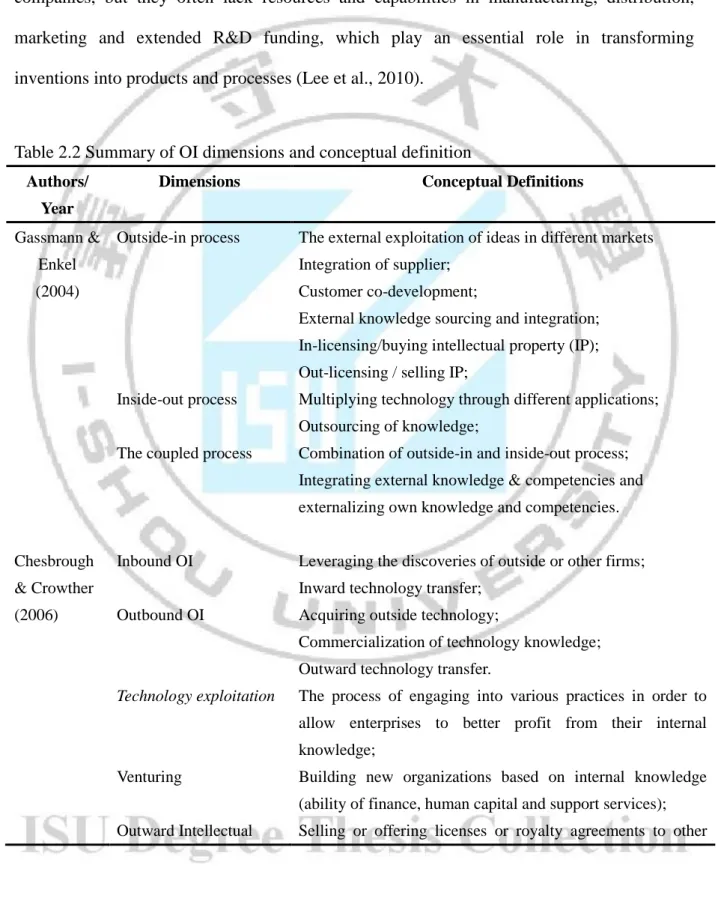

Table 2.2 Summary of Open Innovation dimensions and conceptual definition…………... 16

Table 3.1 Number of enterprises by size of enterprise in Ho Chi Minh (2008)………... 31

Table 3.2 Number of manufacturing industries by size of enterprise in Viet Nam (2008) 32 Table 3.3 Surveyed Open Innovation practices………. 34

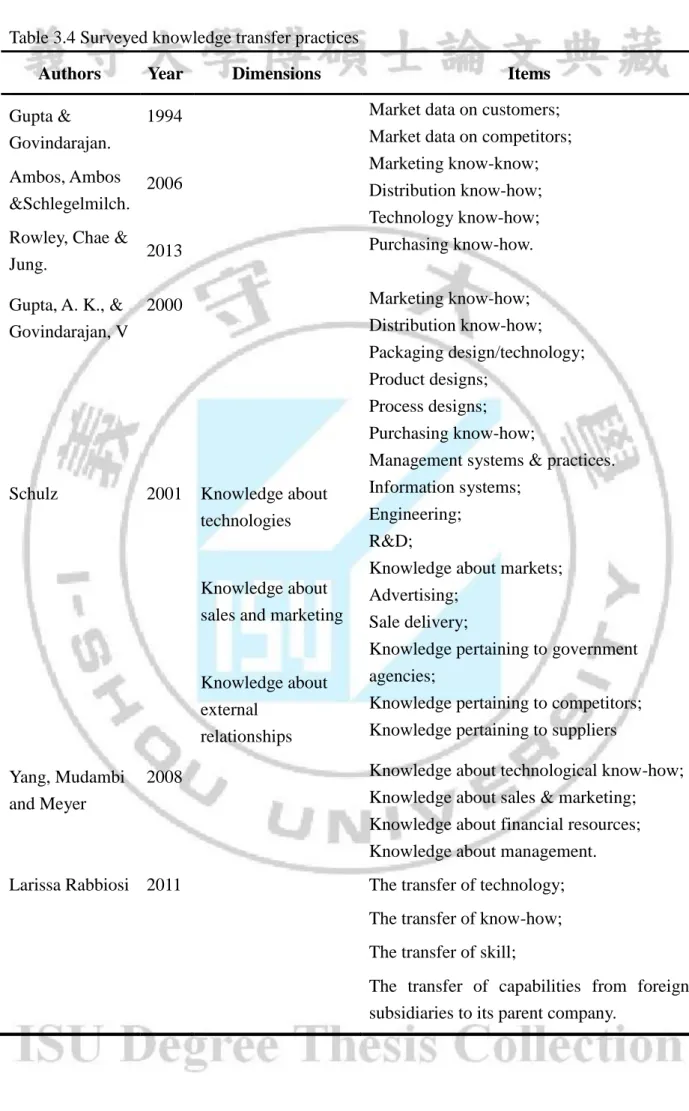

Table 3.4 Surveyed knowledge transfer practices………. 36

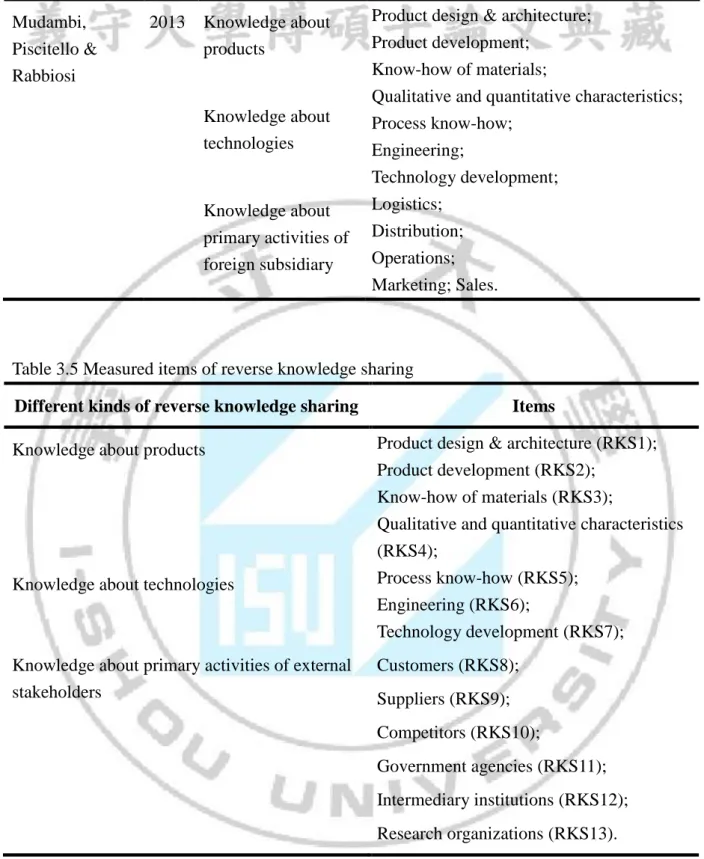

Table 3.5 Measured items of reverse knowledge sharing……….. 37

Table 4.1 Characteristics of the sample ………. 41

Table 4.2 Distribution of sample across industries and size classes……….. 42

Table 4.3 Distribution of respondents across tenures and working experience………. 42

Table 4.4 Component Matrix………... 43

Table 4.5 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation Matrix Among Variables……….. 48

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE vi

List of Figures

Figure 2.1 Closed Innovation Model………... 12Figure 2.2 Open Innovation Model………... 12

Figure 2.3 Knowledge trasfer in Vietnam……… 19

Figure 2.4 The value net for co-opetition……… 21

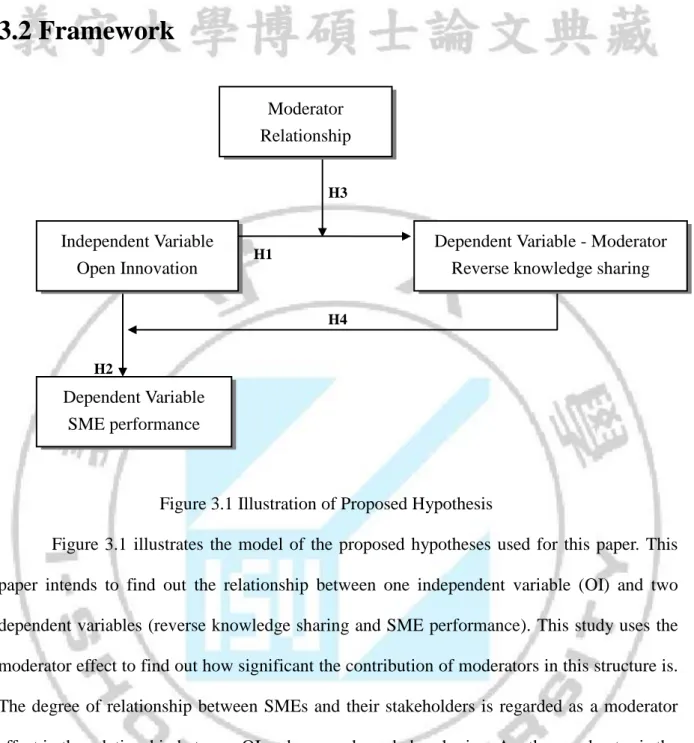

Figure 3.1 Illustration of Proposed Hypothesis ……….. 30

OPEN INNOVATION, REVERSE KNOWLEDGE SHARING & SME PERFORMANCE vii

List of Abbreviations

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

GSO General Statistics Office

EC European Commission

EURIS European Collaborative and Open Regional Innovation Strategies

ERIA Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia

IFC International Finance Corporation

MNCs Multinational Corporations

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OI Open Innovation

R&D Research and Development

SMEs Small and Medium-sized enterprises

USA United States of America

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Research Background

In an era of increasing globalization, the global economy becomes more intertwined,

interdependent and communicated in global information flows. Commercial activities have

not only been conducted within one country but have required involvement of many

economies at different levels. This multi-state cooperation is characterized by the rapidly

growing expansion of multinational business activities, plurilateral agreements, cross-national

technology exchanges. The sovereignty of economies around the world seems more and more

blurred. Businesses have gone beyond their national boundaries for innovative activities

because of the significantly strong development of information technology and increasingly

strong competition. It is now widely agreed that one enterprise cannot develop its own

business without outside partnerships. All enterprises should work together for successful

business operations. In the wake of the global economic crisis, the cooperation among

business actors becomes significantly flourished because of following main reasons. First,

connectivity is portrayed as the driver or framework for innovation (Cornell-University et al.,

2013). Second, the engagement into global economy can allow firms to get involved in flows

of foreign exchange where their interest rates are lower than ones in their domestic market

(Ghosh & Chandrasekhar, 2009).

The business model now is very different from one century ago. In the past, the

traditional or closed business model allowed innovative ideas to come mainly from individual

innovators, imitators and R&D departments of large companies. According to Koldzin (2011,

p.35) “Traditional Closed Innovation model is based on an idea, where innovation takes place

within a single company or research group, and protecting the innovation is the key issue”. Also, the role of outstanding individuals was significantly served as nuclear when managers

and new business model. Globalization is characterized by the increasing mobility of skilled

workers and capability of external suppliers, fast venture capital flow across multiple

organizations and national boundaries, and the growth of external options (Chesbrough,

2003a). Innovation is now more global, more dispersed than one century ago

(Cornell-University et al., 2013). Large companies are no longer the main idea generators.

The leading industrial firms have faced increasingly harsh competition from start-ups

(Chesbrough, 2003b). A major portion of great ideas come from startups, universities and

research institutes, nonprofit organizations and foundations. As a result, enterprises are

motivated to change their business model to accommodate the increasingly difficult business

conditions. Therefore, the closed business model has been replaced by a new alternative called

“Open Innovation”. This new business model can allow enterprises to adopt newly developed ideas and perceptions not only from within but also outside the firms’ boundaries.

SMEs account for the largest number of enterprises and employees in the world. Over

95% of enterprises are SMEs and they occupy 60%-70% of employment in most OECD

countries (OECD, 2000). In the European Union, SMEs account for over 99% of businesses

(OECD, 2009). SMEs make up around 95% - 99% of the firms in member states of ASEAN

and SMEs are dominant in Vietnam with about 97.5% of all businesses in 2011 (ERIA, 2014).

Based on the database of GSO (2010), the number of SMEs in Vietnam has been growing

rapidly, particularly since Vietnam became an official member of the World Trade

Organization at the end of 2006 (Table 1.1). Because of their numerical dominance, SMEs are

portrayed as a heartbeat or driver of economic development in the world in general and

developing countries in particular. “Fostering a dynamic SME sector should be seen as a

priority amongst economic development goals, in both industrialized and emerging countries”

(IFC, 2010, p.03). More importantly, SMEs have become important engines of innovations

and inventions. According to a statistics from the USA, the percentage of R&D spending

24% in 2005 when large companies suffered a considerable decline from around 75% to 37%

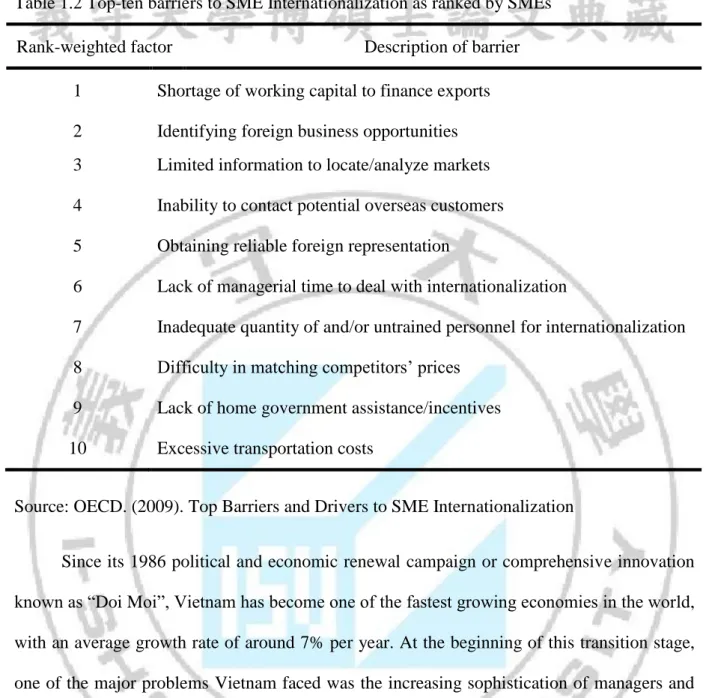

of R&D spending in the same period (Vanhaverbeke, 2009). However, SME development is

likely to confront a variety of major challenges. Lack of finance is cited as one of the major

obstacles to SME development. Limitation of external information coming from government

or competitor is also portrayed as one of the serious barriers to SME internationalization

(Table 1.2). Many SMEs around the world, especially in emerging markets, require capital to

meet their financial needs but access to funding has historically been severely constrained by

the financial services sector. The number of formal SMEs in emerging markets who are not

served or underserved by credit is 45%-55% and 21%-24% respectively (IFC, 2010). The

majority of SMEs depend on a few customers who purchase large amounts of goods and

services. The increasing changes of customer requirements will affect SMEs’ production and

the close relationship between firms and customers should be considered. This firm-customer

relationship not only allows SMEs to quickly respond to their changing demands but provides

stable and growing revenue for firms.

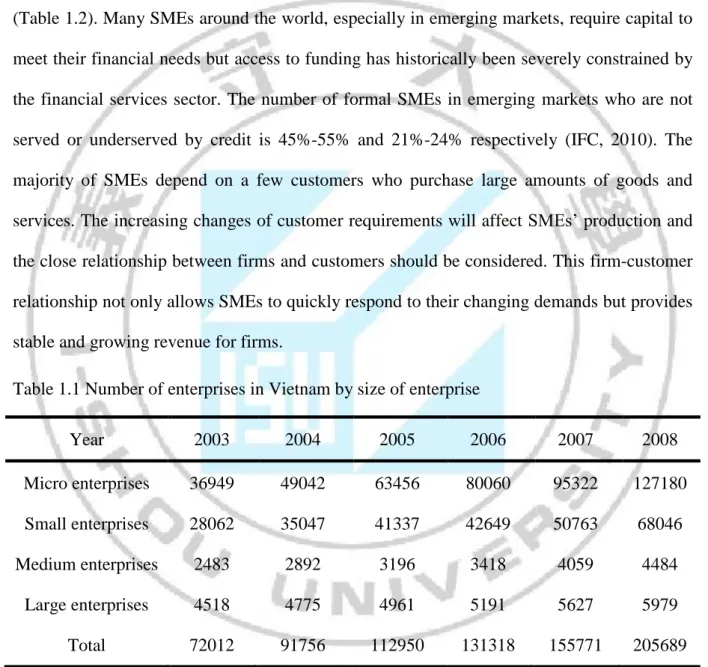

Table 1.1 Number of enterprises in Vietnam by size of enterprise

Year 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Micro enterprises 36949 49042 63456 80060 95322 127180 Small enterprises 28062 35047 41337 42649 50763 68046 Medium enterprises 2483 2892 3196 3418 4059 4484 Large enterprises 4518 4775 4961 5191 5627 5979 Total 72012 91756 112950 131318 155771 205689

Table 1.2 Top-ten barriers to SME Internationalization as ranked by SMEs

Rank-weighted factor Description of barrier

1 Shortage of working capital to finance exports

2 3

Identifying foreign business opportunities Limited information to locate/analyze markets

4 Inability to contact potential overseas customers

5 Obtaining reliable foreign representation

6 Lack of managerial time to deal with internationalization

7 Inadequate quantity of and/or untrained personnel for internationalization

8 Difficulty in matching competitors’ prices

9 Lack of home government assistance/incentives

10 Excessive transportation costs

Source: OECD. (2009). Top Barriers and Drivers to SME Internationalization

Since its 1986 political and economic renewal campaign or comprehensive innovation

known as “Doi Moi”, Vietnam has become one of the fastest growing economies in the world, with an average growth rate of around 7% per year. At the beginning of this transition stage,

one of the major problems Vietnam faced was the increasing sophistication of managers and

policy makers (Napier, 2006). As Vietnamese domestic enterprises are dominated by the SME

sector, the key question faced by policy makers is how SMEs can effectively enter into

knowledge based and globally competitive economies. Among various initiatives being

proposed to accelerate SMEs’ ability to internationalize, innovation has attracted much

attention from business communities. Firms are motivated to conduct their innovation as open

1.2 Research Significance

Enterprises have to consider operating their business activities beyond their domestic

market for many reasons. MNCs have taken advantages of having subsidiaries in developing

countries in which low-wage workforce and underexploited natural resources are more

available than in developed counterparts. Unlike MNCs, start-ups and SMEs are confronted

with different problems like financial constraints and technology for the expansion of their

business activities. The world economy has witnessed the growing flows of ideas,

technologies, human resources. As a result, enterprises are forced to change methods of

operation in a variety of ways in response to the changing trends of the global economy. The

appearance of the OI approach potentially replaces for Closed Innovation. However, many

research studies have been largely conducted to investigate Closed Innovation rather than OI.

In addition, the viability and desirability of a Closed Innovation approach should be renovated

to access and take new ideas to market as knowledge is now more globally distributed

(Chesbrough, 2003a). As a result, the requirement for more understanding about OI should be

clarified in different business contexts.

Most research has focused on the adaptation of OI approaches and practices in

multinational firms (Chesbrough, 2003a; Mortara & Minshall, 2011; Ades et al., 2013). For

example, some high-tech multinational companies that have been investigated include IBM

(Chesbrough, 2003a) and Procter & Gamble (Dodgson et al., 2006). OI literature that focuses

on SMEs is under-researched (Van de Vrande et al., 2009; Bianchi et al., 2010; Lee et al.,

2010) although they account for the largest number of companies in all economies (Gassmann

et al., 2010). However, OI activities have been utilized in a variety of industries such as

chemicals, medical devices, aerospace, etc (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006). Regardless of the

roles played in OI paradigm should not be neglected (Lindegaard, 2011). Although, a growing

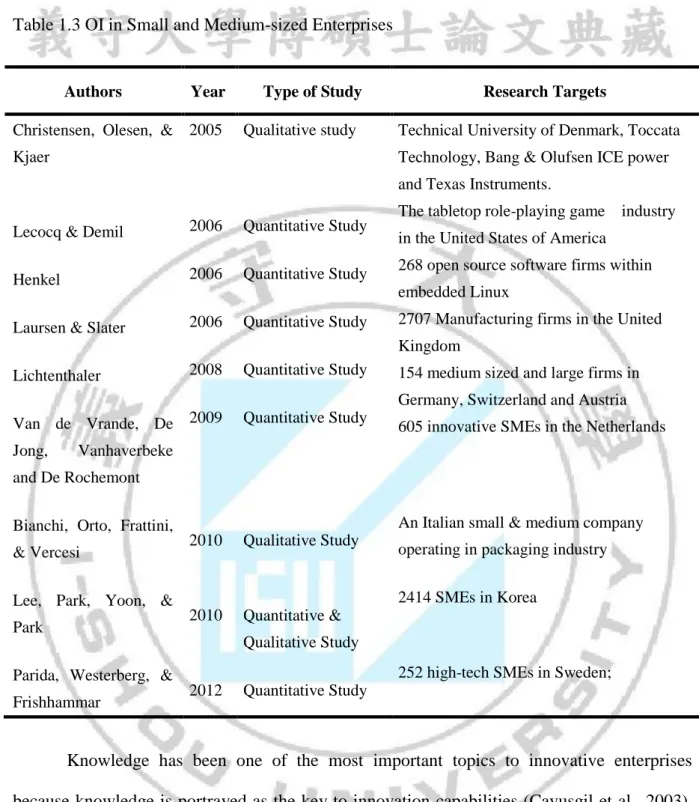

number of studies have investigated OI in SMEs, they have tended to focus on SMEs in

developed economies like European nations (Van de Vrande et al., 2009; Laursen & Salter,

2006). The adoption of OI in SMEs in Asian countries generally and in developing countries

particularly remains relatively scarce (for an overview and summary, see Table 1.3). The

research on OI in a variety of industries and countries, not only in the USA or Europe but in

Asia should be considered in order to “determine the frequency and importance of various

practices and context factors” (Huizingh, 2011, p.07). Lee et al., (2010) has so far attempted to empirically study OI in an Asian country (South Korea).

Table 1.3 OI in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

Authors Year Type of Study Research Targets

Christensen, Olesen, & Kjaer

Lecocq & Demil Henkel Laursen & Slater Lichtenthaler

Van de Vrande, De Jong, Vanhaverbeke and De Rochemont Bianchi, Orto, Frattini, & Vercesi

Lee, Park, Yoon, & Park

Parida, Westerberg, & Frishhammar 2005 2006 2006 2006 2008 2009 2010 2010 2012 Qualitative study Quantitative Study Quantitative Study Quantitative Study Quantitative Study Quantitative Study Qualitative Study Quantitative & Qualitative Study Quantitative Study

Technical University of Denmark, Toccata Technology, Bang & Olufsen ICE power and Texas Instruments. The tabletop role-playing game industry in the United States of America 268 open source software firms within embedded Linux 2707 Manufacturing firms in the United Kingdom 154 medium sized and large firms in

Germany, Switzerland and Austria 605 innovative SMEs in the Netherlands

An Italian small & medium company

operating in packaging industry 2414 SMEs in Korea

252 high-tech SMEs in Sweden;

Knowledge has been one of the most important topics to innovative enterprises

because knowledge is portrayed as the key to innovation capabilities (Cavusgil et al., 2003).

Many researchers have paid more attention on knowledge transfer from MNCs’ headquarters

to their subsidiaries rather than knowledge transfer in the opposite direction. Nevertheless, we

cannot deny the critical role played by subsidiaries in which many MNCs exploit and discover

ideas, and methods or technologies, thereby strengthening their business activities in host

foreign countries. Some papers have demonstrated the extreme importance of knowledge

innovation in MNCs (Phene & Almeida, 2008), creation of competitive edge of MNCs (Zhou

& Frost, 2003), and development of firm-specific advantages creation in MNCs (Birkinshaw

et al., 2008).

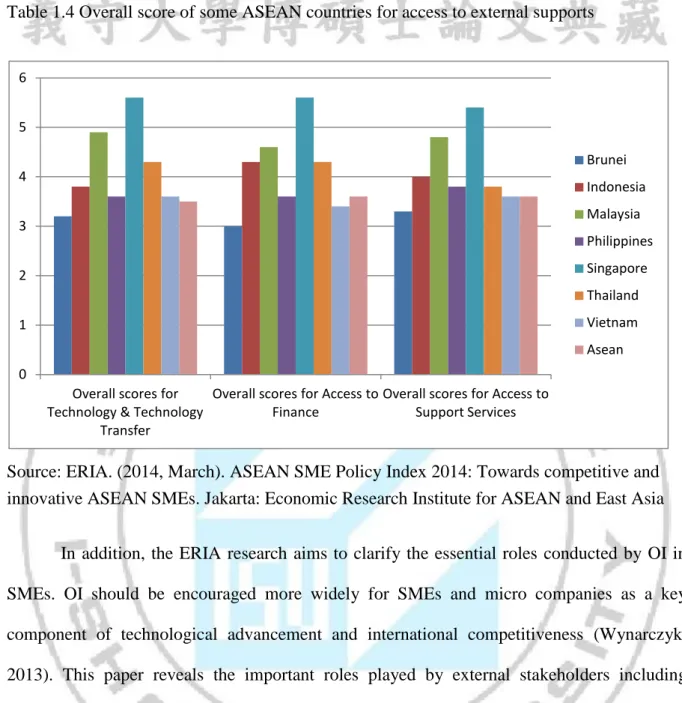

According to a report of ERIA (2014), ASEAN members find it difficult to access

supporting externalities such as finance, technology, competitive markets. In Vietnam, SMEs

have lower degree of approaching supporting externalities than more advanced ASEAN

economies including Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand (Table 1.4). It

may assume that Vietnamese SMEs should accelerate outside relationship for access to

finance, advanced technology, human resources, etc, in order to enhance their competitiveness

or to achieve further economic growth. In order for SMEs to become more competitive,

innovative, and dynamic, external stakeholders like government agencies play an important

role. However, the administrative processes and procedures are an unavoidable burden on

start-up SMEs. Governments could pay more attention to providing suitable support policies

including both clear objectives and supported targets to SMEs (ERIA, 2014). Government

also could build financial service like Venture Capital Funds or enhanced administrative

Table 1.4 Overall score of some ASEAN countries for access to external supports

Source: ERIA. (2014, March). ASEAN SME Policy Index 2014: Towards competitive and

innovative ASEAN SMEs. Jakarta: Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia

In addition, the ERIA research aims to clarify the essential roles conducted by OI in

SMEs. OI should be encouraged more widely for SMEs and micro companies as a key

component of technological advancement and international competitiveness (Wynarczyk,

2013). This paper reveals the important roles played by external stakeholders including

customer, supplier, governmental agency, university in OI adoption within SMEs context.

Because of the strategic positions of open communities to improve stainable development,

SMEs in developing countries should focus on building strong relationships with external

stakeholders in their business orientation. Regardless of potential risks and challenges,

Vietnamese SMEs should recognize the opportunities and potential available in the global

marketplace. 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Overall scores for Technology & Technology

Transfer

Overall scores for Access to Finance

Overall scores for Access to Support Services Brunei Indonesia Malaysia Philippines Singapore Thailand Vietnam Asean

1.3 Problem Statement and Research Objectives

The core problem which this study intends to investigate is two-fold: a) whether there

is positive relationship between OI and reverse knowledge sharing within SMEs; and b)

whether external stakeholders can positively moderate the relationship between OI and

reverse knowledge sharing within SMEs. The following questions will be addressed:

1. Does OI positively influence reverse knowledge sharing in SMEs?

2. What are the most popular external partners in the OI approach of SMEs?

3. To what extent do external stakeholders strengthen the relationship between OI and

reverse knowledge sharing in SMEs?

4. What conditions appear to enhance the possibility of reverse knowledge sharing under

Chapter 2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Open Innovation

The term “Open Innovation” was introduced by Henry Chesbrough in 2003 to describe an innovation paradigm shift from a Closed Innovation in which firms have to

conduct innovation activities on their own to an OI model that combines both internal and

external sources including technology, knowledge to create and commercialize new products,

services or process (Chesbrough, 2003a)

2.1.1 Open Innovation Model

Firgure 2.1 and 2.2 below illustrate differences between closed and OI models. In both

the main stages include research and development, the Closed Innovation model illustrates a

sefl-contained process whereas OI model shows an unbounded one. The former includes only

one way to enter and one way out to the marketplace but the latter includes many exits to

reach the current market or to build a new market. However, these differences are just the tip

of the iceberg, and contrasting principles between the two different innovation models are

Figure 2.1 Closed Innovation Model

Source: Chesbrough, H. (2003a). OI: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business School Press

Firgure 2.2 Open Innovation Model

Source: Chesbrough, H. (2003a). OI: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business School Press.

A company with a model of Closed Innovation completely controls all aspects of the

innovation process and their discoveries are kept secret. The Closed Innovation approach is

characterized by its self-control: “If you want something done right, you’ve got to do it

yourself” (Chesbrough, 2003a, p.36). Companies with the Closed Innovation have to create their own ideas, and then do processes of assimilating those ideas into their products by

themselves (Chesbrough, 2003a). As shown in Figure 2.1, a project in the closed paradigm

based on firms’ own science and technology foundations projects are launched and external

technology sources cannot contribute any value to the business process. Many companies like

Dupont, IBM and AT&T or scientists like Thomas Edison operated with the Closed

Innovation which worked very well for most of the 20th century, but a number of factors, both

external and internal, corroded the foundation of Closed Innovation (Chesbrough, 2003a).

Also, Lichtenthaler (2008) showed that companies that had followed the Closed Innovation

paradigm started to realize the importance of external ideas in order to keep up with their

competitors. One of the most important characteristics that distinguish OI from Closed

Innovation is that the OI encourages firms to search for appropriate outside partners and take

advantage of strengths available in surrounding businesses rather than relying on solely

internal administration and R&D departments. Chesbrough (2003a) provides a comparison of

the principles of both models (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Contrasting Principles of Closed and OI

Closed Innovation Principles OI Principles

The smart people in our field work for us.

To profit from R&D, we must discover it, develop it, and ship it ourselves.

If we discover it ourselves, we will get it to market first.

The company that gets an innovation to market first will win.

If we create the most and the best ideas in the industry, we will win.

We should control our innovation process, so that our competitors don’t profit from our ideas.

Not all the smart people work for us. We need to work with smart people inside and outside our company.

External R&D can create significant value; internal R&D is needed to claim some portion of that value.

We don’t have to originate the research to profit from it.

Building a better business model is better than getting to market first.

If we make the best use of internal and external ideas, we will win.

We should profit from others’ use of our innovation project, and we should buy others’ intellectual property whenever it advances our own business model.

Source: Chesbrough, H. (2003a). OI: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Harvard Business School Press.

2.1.2 Dimensions of Open Innovation

OI is a broad concept. Most studies have divided the concept into inbound and

outbound OI dimensions (Chesbrough & Crowther, 2006, Chesbrough et al., 2006). Inbound

OI refers to the acquisition and transfer of external ideas and technologies into the firm when

outbound OI refers to the transfer of internal resources to external firms (Chesbrough &

Crowther, 2006). Also, OI comprises outside-in and inside-out movements of technologies

and ideas (Lichtenthaler, 2008). While the inside-out process refers to generating and

accelerating profits by transferring firms’ innovative ideas to markets by selling or licensing

out intellectual property, the outside-in process involves the process of absorbing external

knowledge to its existing knowledge through business network and collaboration with other

external institutions (Wynarczyk, 2013). Van de Vrande et al., (2009) divided OI into two

dimensions in terms of technology. They include technology exploration and technology

exploitation. However, the combination of both exploration and exploitation is more popular

than one way movement because it is suitable for firms of all sizes (Enkel et al., 2009). As a

result, three core innovation processes suggested including outside-in, inside-out and coupled

process (Gassmann & Enkel, 2004; Enkel et al., 2009). The couple process relates to

co-creation with complementary partners or cooperation with other companies in strategic

networks (Gassmann & Enkel, 2004; Enkel et al., 2009). The three core processes that relate

to the three knowledge processes are exploitation, exploration and retention (Lichtenthaler

and Lichtenthaler, 2009). Conceptual definitions of dimensions are presented in Table 2.2.

Empirical studies investigating what the most important dimension of OI is show

controversial results. Various empirical studies report that inbound activities bring more

benefits for firms. Chesbrough and Crowther (2006) interviewed twelve companies, then

identified that all firms in the sample participated in some inbound activities like technology

company Deutsche Telekom. Eleven OI activities conducted by Deutsche Telekom showed

that this service company focuses more on outside-in process than its inside-out counterpart

(Rohrbeck et al., 2009). Meanwhile other research supports outbound dimension of OI.

Qualcomm is one of the most popular companies which are very successful with outbound OI

because it takes more profit from licensees of its code division multiple access technology and

chipsets that are used by other cell-phone manufacturers like Nokia and Motorola

As compared with multinational companies with operations in many countries, SMEs

usually have a narrow scope of operation because they often do business only locally or

regionally. A lack of internal resources like technology is one of the reasons inbound activities

play a critical role in SMEs. SMEs may be more flexible and more responsive than large

companies, but they often lack resources and capabilities in manufacturing, distribution,

marketing and extended R&D funding, which play an essential role in transforming

inventions into products and processes (Lee et al., 2010).

Table 2.2 Summary of OI dimensions and conceptual definition

Authors/ Year

Dimensions Conceptual Definitions

Gassmann & Enkel (2004)

Outside-in process

Inside-out process

The coupled process

The external exploitation of ideas in different markets Integration of supplier;

Customer co-development;

External knowledge sourcing and integration; In-licensing/buying intellectual property (IP); Out-licensing / selling IP;

Multiplying technology through different applications; Outsourcing of knowledge;

Combination of outside-in and inside-out process; Integrating external knowledge & competencies and externalizing own knowledge and competencies.

Chesbrough & Crowther (2006)

Inbound OI

Outbound OI

Leveraging the discoveries of outside or other firms; Inward technology transfer;

Acquiring outside technology;

Commercialization of technology knowledge; Outward technology transfer.

Technology exploitation

Venturing

Outward Intellectual

The process of engaging into various practices in order to allow enterprises to better profit from their internal knowledge;

Building new organizations based on internal knowledge (ability of finance, human capital and support services); Selling or offering licenses or royalty agreements to other

Property (IP) Employee Involvement Technology exploration Customer involvement External networking External participation Outsourcing R&D Inward licensing of IP

organizations to better profit from your intellectual property (patents, copyrights or trade-marks);

Leveraging the knowledge and initiatives of employees who are not involved in R&D, for example by taking up suggestions, exempting them to implement idea, or creating autonomous teams to realize innovations;

Combination of activities which help enterprises to acquire new knowledge and technologies from the surrounding environment;

Directly involving customers in your innovation process, for example by doing research about their needs or by developing products based on customers’ specifications or modifications of products similar like yours;

Drawing on or collaborating with external network partners to support innovative processes, for example for external knowledge or human capital;

Equity investments in new or establish enterprises in order to gain access to their knowledge or to obtain other synergies; Buying R&D services from other organizations (universities, research institutions, commercial engineers or suppliers); Buying or using intellectual property of other organizations to benefit from external knowledge.

2.1.3 Open Innovation in SMEs

Innovation has long played a key role in the growth and internalization of SMEs. An

competitive environment has forced SMEs to develop innovative products and competitive

behaviours. This has challenged SMEs because they have less experienced manager with less

commercial experience. Limitations in finance and physical resources is a leading problem for

SMEs to achieve success (OECD, 2009). This became more serious after the financial crisis

of 2008-2009. One of the reasons is that banks and lending institutions do not want to engage

into risky ventures (OECD, 2000). In addition, SMEs in developing countries find it more

difficult to access external supporting sources than in developed counterparts. One way to

address such barriers is by widening their innovation process in order to profit from available

sources of external actors.

Inbound activities of OI seem the most important trend for SMEs. Van de Vrande et al.,

(2009) showed that SMEs are more likely to be involved in technology exploration rather than

technology exploitation practices, based on data collected from 605 manufacturing and

services firms in Netherlands. In particular, they found that SMEs which in-licensed

technologies from other partners doubled SMEs which out-licensed their own technologies.

Other studies show that firms undergoing outbound activities may face some difficulties. For

example, outbound activities are articulated with higher level of managerial challenges due to

the imperfections in the markets for technologies (Lichtenthaler & Ernst, 2007, as cited in

2.2 Reverse Knowledge Sharing

2.2.1 Reverse Knowledge Sharing

Knowledge flows within MNCs occur in many different directions (Gupta &

Govindarajan, 2000). Three popular kinds of knowledge flow include conventional, reverse

and relevant knowledge transfer (Yang et al., 2008). Knowledge flow that is transferred from

headquarter to its subsidiaries is conventional knowledge transfer. Knowledge can conversely

be transferred from subsidiaries to their parent company in a reverse knowledge transfer

(Ambos et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008). Naiper (2005) shows that knowledge transfer is

conducted in bidirectional movements in Vietnam. Vietnamese companies are main recipients

and foreign counterparters are senders in knowledge transfer and vice verse in reverse

knowledge transfer. Both Vietnamese companies and foreigners that play two roles as

receivers as well as senders and get different benefits in the exchange of knowledge. In this

study, the focus will be on reverse knowledge transfer in Vietnam.

Figure 2.3 Knowledge trasfer in Vietnam

In the past, the terms knowledge sharing and knowledge transfer have been used

interchangeably (Schwartz, 2006) but more recently they have been discussed separately.

Firstly, one of separating characteristics between knowledge sharing and transfer is that

knowledge can transfer in bidirectional flow for sharing whereas knowledge can transfer in

unidirectional flow in the transfer (Charrel & Galarreta, 2007). Secondly, knowledge transfer

is considered a critical foundation for knowledge sharing and the goal of knowledge transfer

is to promote and facilitate knowledge sharing (Awad & Ghaziri, 2007). As a result,

knowledge transfer includes knowledge sending and receiving whereas knowledge sharing

encourages the exchanging of knowledge between individuals, between or within teams, or

between individuals and knowledge bases (Awad & Ghaziri, 2007). Also, “the knowledge

sharing may be focused or unfocused, but it usually does not have a clear objective”

(Schwartz, 2006, p.542). Both knowledge transfer and reverse knowledge transfer consider

headquarters and subsidiaries as knowledge sender or receiver. Knowledge creators or

receivers have not been defined in the SMEs’ context in prior studies. Therefore, this study

uses reverse knowledge sharing mainly based on reverse knowledge transfer.

2.2.2 Reverse Knowledge Sharing in SMEs

Reverse knowledge sharing within MNCs is different from with SMEs because for

multinational companies with business activities carried out in different markets reverse

transfers of knowledge mainly comes from subsidiaries to their headquarters (Barlett &

Ghoshal, 1989; Gupta & Govindarajan, 2000; Ambos et al., 2006). However there is little

mention in the literature of reverse knowledge sharing and its actors in small or medium

enterprises. Knowledge that is obtained using the OI model may be obtained from different

sources. Local partners are considered as knowledge creators for SMEs because they usually

conduct their business operation in a region. Research shows that the greater part of the

competitors, and clients (Prince, 1999, as cited in Kerste & Muizer, 2002). Particularly, SMEs

consider business partners and universities as critical actors positively affecting product

innovativeness (Gudda et al., 2013). According to the value net framework developed by

Brandenburger & Nalebuf (cited in Levy & Powel, 2004), the establishment of cooperation

with multiple partners like customers, competitors, suppliers should be highlighted (Figure

2.4). In addition, knowledge that SMEs absorb from their close partners as customers and

suppliers is very valuable for new product development (Jetter et al., 2006). Therefore, it is

assumed that reverse knowledge sharing can be conducted between SMEs and external

stakeholders like suppliers, consumers, business alliances, competitors and universities or

research institutions.

Figure 2.4 The value net for co-opetition

Source: Levy & Powel. (2004). Strategies for growth in SMEs: The role of information and information systems

2.3 Hypothesis Development

2.3.1 The Effects of Open Innovation in SMEs

The critical difference between Closed and Open Innovation can be found in the ways

enterprises test the viability of their ideas (Chesbrough, 2003b). Three main characteristics of

illustrating Closed Innovation are (1) “A strong but very narrow scientific and technical body

of competencies, in their own area of interest”; (2) “R&D carried out, in a very unstructured

fashion, inside organizational units devoted to technical assistance activities”; (3) “A focus on

markets where customers are relatively low demanding in terms of product innovation and

where competition is rather weak” (Chiaroni et al., 2010, p. 228). External knowledge also

seems very limited in Closed Innovation paradigm (Chesbrough et al., 2006), as a result, it

assumes that Closed Innovation does not allow for knowledge flow, inflow or outflow. In

contrast, OI is “all about leveraging and exploiting knowledge” (Chiaroni et al., 2010, p.226).

OI is defined as “the use of purposive inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate

internal innovation, and to expand the markets for external use of innovation” (Chesbrough et

al., 2006, p.01), therefore, the prevalence of open over Closed Innovation models is because

the former can encourage the knowledge transfer between open communities.

One critical mission of the OI model is to help enterprises gain access to external

knowledge, therefore, the quality of OI can be measured by the effectiveness of the

knowledge/information inflow. For MNCs, a multinational telecommunication company

named Deutsche Telekom can serve as a prominent example. The majority of

company-specific innovations in Deutsche Telekom come from inflow of information

generated by its suppliers such as Ericson, Nokia Siemens Networks and Alcatel-Lucent

(Rohrbeck et al., 2009). For SMEs, OI can offer better access to modern technologies and

in-house (Chesbrough, 2003a; Chesbrough et al., 2006). Two examples demonstrate this. First,

a large number of SMEs with OI approach have had more opportunities to access R&D

funding from the UK government with easier registration of patents than SMEs with Closed

Innovation (Wynarczyk, 2013). Second, Quilts of Denmark engaged into the OI approach to

gain valuable knowledge such as temperature regulation and technology of Temprakon from

external partners including sleep researchers and space agency NASA. These external

resources largely contributed to the production of a temperature regulating pillow, thereby

helping Quilts establish subsidiaries in thirty countries since it started business in 2000

(EURIS, 2011).

Due to the important role that the introduction of innovative products, services, and

processes play in firm growth, enterprises engage in OI to accelerate product development. OI

is designed to enhance the introduction of innovative products, service, processes or business

models (Chesbrough, 2006). In doing so, employees are stimulated to increase their

productivity and the quality of their work (Chesbrough, 2006). SMEs are more able to create

new innovative products and services when they collaborate with innovation partners

(Spithoven, et al., 2013). Moreover, some previous investigations demonstrated that the

impact of innovation on SME performance is a positive effect (Rosenbusch et al., 2010). The

innovation-performance relationship is greater in a collectivist culture as in Asian countries

than in individualist culture like the USA (Rosenbusch et al., 2010). Firms pursuing inbound

activities of the OI model are positively linked to innovative performance of SMEs (Parida et

al., 2012). In addition direct effects on product manufacture, OI allows resource-scarce firms

to benefit more from manufacturing expenditure and time saving as they can source available

external resources. According to a self-reported data by entrepreneurs and managers, Massa

and Testa (2008) found that more than 30% of turnover for about half of the surveyed SMEs

comes from innovative activities. It is assumed that there is a positive influence of the OI

and large enterprises is nearly similar, 8.8% and 8.9% respectively, even though SMEs

introduce fewer new products/services to the market than large counterparts (Spithoven, et al.,

2013). These perspectives provide consistent real-life evidence to support two following

hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): OI is positively related to the degree of SMEs reverse knowledge sharing.

2.3.3 Relationship as an Enabler of both Open Innovation and

Reverse Knowledge Sharing

External networking is one of the important practices of OI (Vrande et al., 2009). In

external networking, relationships between firms and external sources of social capital,

including individuals and organizations are very necessary (Vrande et al., 2009). External

relations have been portrayed as forms of OI. Firms tend to open their boundaries to get closer

to different external stakeholders, including suppliers (Li & Vanhaverbeke, 2009), customers

(Gassmann et al., 2006), intermediary organizations (Lee et al., 2010), universities & research

centers (Chiaroni et al., 2010; Buganza & Verganti, 2009) and even competitors (Lim et al.,

2010). The relationship between firms and these stakeholders in a dense innovation network

becomes more necessary in the knowledge-driven economy (Bullinger et al., 2004).

Chesbrough (2003a) showed MNCs should consider using open communities as a routine part

of future development efforts. The practices of building relationship with external

stakeholders become more important for SMEs because one of the major liabilities that SMEs

have confronted is the lack of technical capability and financial resources (Vanhaverbeke et al.,

2012). Therefore, the OI model should involve the relationships between firms and

stakeholders.

When firms adopt the OI model, the advantages of building and maintaining

relationships in MNCs’ context have been published. MNCs have been dependent on multiple

external stakeholders through different kinds of relationship like collaborative relations or

mutually beneficial ones. There are two examples illustrating the effectiveness of establishing

external relationships in MNCs. First, IBM, a US multinational technology and consulting

corporation, recognized that a lack of value-added activities is one of the reasons for losses, as

a result, it held a meeting with one of its largest customers, Citicorp. Also, a corporate website

share ideas about world problems and discuss solutions to these long-standing problems.

Second, the important role of external actors is seen in case of Japanese automotive

manufacturer Toyota. The dense networks provided Toyota an important capability of

knowledge acquisition, in conjunction with generating information required for monitoring

and enforcement (Kogut, 2000). In terms of SMEs, external relationships can allow them to

gain three main advantages, organizational development (e.g. ability of accessing available

resources), completion and competitive advantages (e.g. enhancement of competitive ability)

and performance (e.g. goal achievement) (Street & Cameron, 2007). According to a study of

137 Chinese manufacturing companies, Zeng et al., (2010) reported that cooperation of SMEs

with customers, suppliers and other firms contribute to the innovation process, but one cannot

underestimate other kinds of cooperation like research institutions, universities or

intermediary institutions. This is because the relationship between knowledge partners (e.g.

universities, research organizations) and firms plays an essential role in driving the innovation

process through research partnerships, contract research and consulting (Perkmann & Walsh,

2007). An example is the case of Portugal in which some government agencies are portrayed

as external resources for small firms in order to access knowledge and experience about

potential partners (Sousa & Bradley, 2009). It is clear that relationships between companies

and external stakeholders play an important role in the success of the OI model.

A knowledge monopoly has been largely damaged because of the diffusion of

knowledge to different external stakeholders, including companies, customers, suppliers,

universities, start-ups (Chesbrough, 2003a). For this reason firms should build external

relationships beyond their boundaries to access valuable knowledge. In MNCs, the

relationship between headquarters and foreign subsidiaries can be changed to influence the

level of reverse knowledge transfer (Rabbiosi, 2011). Reverse knowledge transfer depends on

the relationship between the parent company and its subsidiaries (Borini & Fleury, 2011).

the network’s influences on knowledge transfer. Strong ties which are characterized by high trust and close relationships provide a foundation for successful sharing of tacit or complex

knowledge (Fernie et al., 2003). Also, a strong connection rather than a weak one can help

firms more easily exchange all kinds of knowledge (Reagan & McEvily, 2003). It can be

agreed that the external relationship between SMEs with external stakeholders is very

important to effective knowledge sharing.

Given the important role played by external relationships in the OI model as well as

reverse knowledge sharing from external stakeholders to SMEs, provides the basic for this

third hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Relationship can positively moderate the relationship between OI and reverse knowledge sharing.

2.3.4 Reverse knowledge sharing as an Enabler of both Open

Innovation and SME performance

Reverse knowledge has been playing a critical role in both MNCs. The reverse knowledge

flow from subsidiaries to headquarters is an essential source of competitive edge for

multinational firms, whether from developed economies (Ambos et al., 2006; Piscitello &

Rabbiosi, 2006), or developing economies like Brazil (Borini et al., 2012). For example,

reverse knowledge flow not only provides opportunities to evaluate products made in

emerging markets but also allows for rethinking the assumptions underlying the units located

in developed markets, thus multinational companies retain their competitive ability through

knowledge flow from subsidiaries in developing markets (Govindarajan, 2012). If external

knowledge is a factor that can generate competitive edge for MNCs, it seems even more

important for SMEs that are characterized by resource constraint. This suggests the essential

role of reverse knowledge sharing under SMEs context can be hypothesized as:

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Reverse knowledge sharing can positively moderate the relationship between OI and SME performance.

Chapter 3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research Design

The objective of this research is to examine the process of reverse knowledge sharing

from different external stakeholders, and to clarify the approach of OI in SMEs’ context.

Specifically, the main aim of this research is to acquire knowledge about correlations between

OI and reverse knowledge sharing in SMEs’ context.

The following research questions will be addressed in this study:

1. Does OI influence reverse knowledge sharing in SMEs?

2. What are the most popular external partners in OI approach of SMEs?

3. To what extent do external stakeholders strengthen the relationship between OI and

reverse knowledge sharing in SMEs?

4. What conditions appear to enhance the possibility of reverse knowledge sharing under

SMEs context?

This study employs a methodology of quantitative approaches to investigate these

research quesitons. Quantitative approach that is well-known as the administration of

questionnaires to a sample of respondents was conducted in my research because it greatly

3.2 Framework

H2

Figure 3.1 Illustration of Proposed Hypothesis

Figure 3.1 illustrates the model of the proposed hypotheses used for this paper. This

paper intends to find out the relationship between one independent variable (OI) and two

dependent variables (reverse knowledge sharing and SME performance). This study uses the

moderator effect to find out how significant the contribution of moderators in this structure is.

The degree of relationship between SMEs and their stakeholders is regarded as a moderator

effect in the relationship between OI and reverse knowledge sharing. Another moderator is the

reverse knowledge sharing variable. This study aims to investigate whether reverse

knowledge sharing can positively moderate the relationship between OI and SME

performance.

3.3 Sampling Design

Despite the significant contribution of the research of corporations mainly based in

developed countries, few studies have been observed to examine the relationship between OI

H3

H1

H4

Independent Variable Open Innovation

Dependent Variable - Moderator Reverse knowledge sharing Moderator

Relationship

Dependent Variable SME performance

and reverse knowledge sharing in developing regions, mainly the Asian countries. As a result,

this study will be conducted in Vietnam. There are two main reasons why this research aims at

Vietnam. Firstly, Vietnam has played an increasingly important role as a proactive member in

international business activities such as joining negotiations to build up free trade frameworks,

and through participating deeply and comprehensively in multi-lateral forums. Secondly,

Vietnam is becoming a favoured manufacturing location for high-tech multinational

enterprises such as Intel, LG Electronics, Nokia and Samsung because of its cost effective

advantages. Thirdly, the majority of foreign companies in Vietnam usually set up partnerships

with domestic firms so low-tech enterprises have more opportunity to access advanced

technologies. The sample population for this research was taken from manufacturing and

services companies in Ho Chi Minh City. The population was restricted to one city rather than

the whole nation due to differences in geography, level of economic development, and

presence of major industry between states. Ho Chi Minh City, located in the southern part of

Vietnam, with a population of over nine million is a center of commerce, economy and

finance in Vietnam. There were 58394 SMEs (23.3%) of the 250689 registered SMEs in

Vietnam operating business in Ho Chi Minh in the year of 2008 (Table 3.1). In the same year,

the number of small and medium-sized businesses accounted for 23.5% and 21% respectively.

According to the official statistics of Vietnam (2010), Ho Chi Minh City had the highest

number of SMEs in the country, making up 28.4% of nation’s enterprises in 1 January 2009. Table 3.1 Number of enterprises by size of enterprise in Ho Chi Minh (2008)

Enterprises Total Micro Small Medium Large

Vietnam 250689 127180 68046 4484 5979

Ho Chi Minh 58394 40132 15983 933 1346

(23.3%) (31.6%) (23.5%) (21%) (22.5%)

The definition of a SME is various in different contexts. Because this research is

carried out in Vietnam, we define SMEs as firms with less than 300 employees (GSO, 2010).

The sample focuses on two size classes including small-sized with 10 – 49 employees and

medium-sized enterprises with 50 – 299 employees (GSO, 2010). The number of SMEs is too

large to survey all categories, so the survey excludes enterprises with less than 10 employees

because such these enterprises belong to micro-sized ones (GSO, 2010) and are unlikely to

engage in OI and knowledge sharing activities.

The study draws on a sample of SMEs in the manufacturing and services industries

because both industries have increased the wide use of knowledge-intensive technologies for

production processes (OECD, 2005). Using firms in manufacturing enterprises in Ho Chi

Minh City as the basis for this research was appropriate for the following reason: in the

manufacturing sector, small and medium firms comprised about 28% and 25% of SMEs in

Vietnam (Table 3.2); the manufacturing sector in Vietnam attracted the largest amount of

foreign investment capital (Jennings, 2012); and the business operation of eleven industrial

zones and one of Vietnam’s only two national science parks (Saigon Hi-tech park) offers many opportunities for low-tech companies to access advanced manufacturing technologies. A

target sample frame of 150 SMEs was identified from Vietnam Association of SMEs. Table 3.2 Number of manufacturing industries by size of enterprise in Vietnam (2008)

Enterprises Total Micro Small Medium Large

Total 250689 127180 68046 4484 5979

Manufacturing 38384 15468 19302 1106 2508

(15%) (12%) (28%) (25%) (42%)

3.4 Data Collection

Based on Oslo Manual guidelines, questionnaire survey was conducted (OECD, 2005).

The questionnaire attached with a cover letter was divided into different sections including

background information (demographic), OI activities, different kinds of knowledge inflows

from stakeholders, relationships between SMEs and their stakeholders, and SME performance.

Both English and Vietnamese versions of the questionnaire were attached in case respondents

are foreigners (For more details, see Appendices B and D). In order to increase the response

rate, all enterprises that had received the questionnaire were promised to receive a summary

report after this survey was completely finished. It is essential to help enterprises which have

done few or no innovation activities to easily understand questions. The survey therefore

started with a pre-test questionnaire. The draft survey was pre-tested during 1st June to 1st July,

2014. Based on the comprehensive evaluation of pre-test survey, the formal questionnaire

came out two weeks later. Since this survey was used to gather data from target respondents

who occupy high-ranking positions in SMEs, questionnaires were not conducted by email.

Data of questionnaires were collected by post and phone interview during 15th July - 15th

October. Three weeks after the first delivery of 150 surveys, reminder letters were sent out to

non-respondents and a total of 50 surveys were returned, resulting in a response rate of 33.34

percent (50/150). A total of five surveys were excluded because they belonged to large-sized

enterprises, resulting in an acceptable response rate of 30 percent (45/150).

3.5 Measures

3.5.1 Open Innovation

This paper employs eight items that were used by many authors (Vrande et al., 2009;

Lichtenthaler, 2008) to measure OI variable (OI) (Table 3.4). A seven-point Likert-type scale

is used to measure for these items, ranging from 1 (the lowest) to 7 (the highest). The

respondents are asked to score the degree of each item according to their organization’s most

typical situation.

Table 3.3 Surveyed OI practices

Authors Year Dimensions Items

Van de Vrande, de Jong, Vanhaverbeke & Rochemont Lichtenthaler 2009 2008 Technology exploitation (3 Items) Technology exploration (5 Items) -Venturing (OI1);

-Outward Intellectual Property (OI2); -Employee Involvement (OI3); -Customer involvement (OI4); -External networking (OI5); -External participation (OI6); -Outsourcing R&D (OI7); -Inward licensing of IP (OI8).

Parida, Westerberg and Frishammar 2012 Inbound OI activities: Technology scouting (3 Items) Horizontal technology (3 Items) Vertical technology

-Observe technology trends;

-View external sources for ideas and knowledge as important;

-Collect information about our industry. -Cooperate and co-develop with other firms (e.g., competitors and/or

non-competitors);

-Regularly network to exchange experiences/ knowledge with partners; -Our network partners contribute with important input

collaboration (3 Items)

Technology sourcing (2 items)

-Involvement of present customers; -Involvement of future potential customers;

-Involvement of end-users

-Regularly contact R & D institutes and universities to access new technology; -Often buy and use new technology (IPRs) from other firms and institutions.

3.5.2 Reverse knowledge sharing

Following Mudambi et al., (2013), reverse knowledge sharing variable (RKS) data are

divided into three categories including knowledge about products, knowledge about

technologies, knowledge about primary activities of foreign subsidiaries (Table 3.4). In the

third category, different kinds of foreign subsidiary in MNCs’ context are replaced by external stakeholders in the SMEs’ context. Based on a study of Zeng et al., (2010), this paper uses six separated stakeholders, including internal stakeholders (customers, suppliers, competitors)

and external stakeholders (government agencies, intermediary institutions, and research

organizations). One of the main reasons behind why I use this study is that paper is conducted

to study in a developing Asian country (China). More specifically, thirteen items that are used

to measure reverse knowledge sharing are presented in Table 3.6. A seven-point Likert scale is

Table 3.4 Surveyed knowledge transfer practices

Authors Year Dimensions Items

Gupta & Govindarajan. Ambos, Ambos &Schlegelmilch. Rowley, Chae & Jung.

1994

2006

2013

Market data on customers; Market data on competitors; Marketing know-know; Distribution know-how; Technology know-how; Purchasing know-how. Gupta, A. K., & Govindarajan, V 2000 Marketing know-how; Distribution know-how; Packaging design/technology; Product designs; Process designs; Purchasing know-how;

Management systems & practices.

Schulz 2001 Knowledge about

technologies

Knowledge about sales and marketing

Knowledge about external relationships Information systems; Engineering; R&D;

Knowledge about markets; Advertising;

Sale delivery;

Knowledge pertaining to government agencies;

Knowledge pertaining to competitors; Knowledge pertaining to suppliers

Yang, Mudambi and Meyer

2008 Knowledge about technological know-how;

Knowledge about sales & marketing; Knowledge about financial resources; Knowledge about management.

Larissa Rabbiosi 2011 The transfer of technology;

The transfer of know-how; The transfer of skill;

The transfer of capabilities from foreign subsidiaries to its parent company.

Mudambi, Piscitello & Rabbiosi 2013 Knowledge about products Knowledge about technologies Knowledge about primary activities of foreign subsidiary

Product design & architecture; Product development;

Know-how of materials;

Qualitative and quantitative characteristics; Process know-how; Engineering; Technology development; Logistics; Distribution; Operations; Marketing; Sales.

Table 3.5 Measured items of reverse knowledge sharing

Different kinds of reverse knowledge sharing Items

Knowledge about products Product design & architecture (RKS1);

Product development (RKS2); Know-how of materials (RKS3);

Qualitative and quantitative characteristics (RKS4);

Knowledge about technologies Process know-how (RKS5);

Engineering (RKS6);

Technology development (RKS7); Knowledge about primary activities of external

stakeholders Customers (RKS8); Suppliers (RKS9); Competitors (RKS10); Government agencies (RKS11); Intermediary institutions (RKS12); Research organizations (RKS13).

3.5.3 Relationship

This paper employs business partners that were used by Zeng et al., (2010).

Relationship variable (RELAT) is measured by the extent of the relationship between their

firms with six partners including customers (R_CUS), suppliers (R_SUP), competitors

(R_COM) and government agencies (R_GOV), intermediary institutions (R_INTER), and

universities (R_UNI). These items were assessed with a seven-point Likert type scale ranging

from 1 (the lowest) to 7 (the highest).

3.5.4 SME performance

The SME performance variable (SME_PER) should refer to the overall firm

achievements, not to single products or product lines. As a result, this paper considers

multiple aspects to evaluate the performance of a firm. Following previous research on SMEs

(for example, Wolff & Pett, 2006; Rosenbusch, et. al, 2011) this study employs four criteria to

assess firm performance. They include return on assets (ROA), return on sales (ROS), total

sales growth (SALE_GROW), and the creation of new products (NEW_PRO). Respondents

are asked to compare their firm to their competitors in the same industry based on four

different items. Each of the items employed a seven-point Likert type scale ranging from 1

(the lowest) to 7 (the highest).

3.5.5 Control variables

Several control variables were employed in this paper. Size (SIZE) was considered

important because micro-sized companies might be less able to innovate than large companies.

Also, large companies can have more innovative performance advantages over smaller ones

because of higher ability of getting access to diversified resources. The classification of firm