中文對話中的同意使用:語用學與社會語言學分析 - 政大學術集成

179

0

0

全文

(2) AGREEMENT IN MANDARIN CHINESE: A SOCIOPRAGMATIC ANALYSIS. BY. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大 Kai-wen Wei. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat A Thesis Submitted to the. n. al Graduate Institute of Linguisticsi v n C U h eFulfillment in Partial of the i h ngc Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. July, 2012.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2012 Kai-wen Wei All Rights Reserved iii. i Un. v.

(4) Acknowledgements. 歷盡千辛萬苦,終於完成這本論文了!論文得以順利產出,一路上得到許多 人的相助。我首先要感謝的就是我的指導教授詹惠珍博士,老師是我在語言學領 域的啟蒙老師,九年來,老師幽默風趣且精闢的上課方式和對論文辛勤的指導, 讓我在學術上擁有無盡的收穫。在學術之外,老師也關心我的生活、分享人生經 驗,教了我許多處事和工作上應有的態度,這些觀念讓我這輩子受益無窮!. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 此外,我還要感謝我的口試委員曹逢甫博士和徐嘉慧博士,對我的論文從草 創階段到完成,給予許多寶貴的意見,使得我的論文更臻完善。在碩士班階段, 我還要感謝蕭宇超老師、黃瓊之老師、何萬順老師和萬依萍老師,感謝老師們課 業上的傳授與協助,使我對語言學的認識更加開闊。另外,還要感謝賴惠玲老師. ‧. 對我的論文和工作溫暖的關心問候。. Nat. y. sit. n. al. er. io. 除此之外,還要感謝許多語言所的夥伴。感謝助教學姊時不時地會關心我的 論文進度,並且用很多過往的經驗幫我加油打氣。感謝 Melody 在工作和論文方 面的情義相挺,還教了我很多工作態度和電腦應用軟體技巧。感謝苡瑄,不會在 我壓力大,時不時打電話過去的時候覺得很厭煩。還要感謝許多經常穿梭在電腦 室和語言所辦公室的學長姊弟妹,大家的每一張笑臉都是我在寫論文的時候最溫 馨的鼓勵!. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 最後,我要感謝我的家人和朋友,感謝他們耐著性子等我畢業。在我進度順 利的時候陪我歡笑,在我失落低潮的時候陪我哭泣。能夠擁有他們是我這輩子最 幸運的事。謹將這本論文獻給我最愛的家人和朋友,感謝你們!. iv.

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... iv TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................... v LIST OF TABLES .......................................................................................................xii LIST OF FIGURES ..................................................................................................... xv LIST OF ABBRIVIATIONS....................................................................................... xvi Chinese Abstract…………………………………………………………………...xviii English Abstract……………………………………………………………………...xx. 政 治 大. Chapter 1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 1. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 1.1. Background of the Study ................................................................................ 1 1.2. The Problem ................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses .............................................................. 2. ‧. 1.4. Organization of This Thesis............................................................................ 3. sit. y. Nat. Chapter 2 Literature Review ...................................................................................... 5. n. al. er. io. 2.1. Speech Act Theory.......................................................................................... 5 2.2. The Cooperative Principle .............................................................................. 6 2.3. Politeness Principles ....................................................................................... 8 2.3.1. Politeness Principle by Lakoff (1973) ............................................... 9 2.3.2. Politeness Principle by Brown and Levinson (1978) ......................... 9 2.3.3. Politeness Principle by Leech (1983) .............................................. 11. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 2.4. Conversational Structure: Adjacency Pairs .................................................. 12 2.5. Agreement as a Speech Act .......................................................................... 14 2.5.1. Definitions of Agreement ................................................................. 14 2.5.2. Speech Act Analysis of Agreement .................................................. 15 2.5.3. Pragmatic Strategies of Agreement .................................................. 16 2.5.4. Social Constraints: Power and Solidarity ........................................ 17 2.5.4.1. The Notion of Power and Solidarity.................................. 17 2.5.4.2. Gender Differences in Power and Solidarity ..................... 18 2.5.5. Linguistic Features of Agreement .................................................... 20. v.

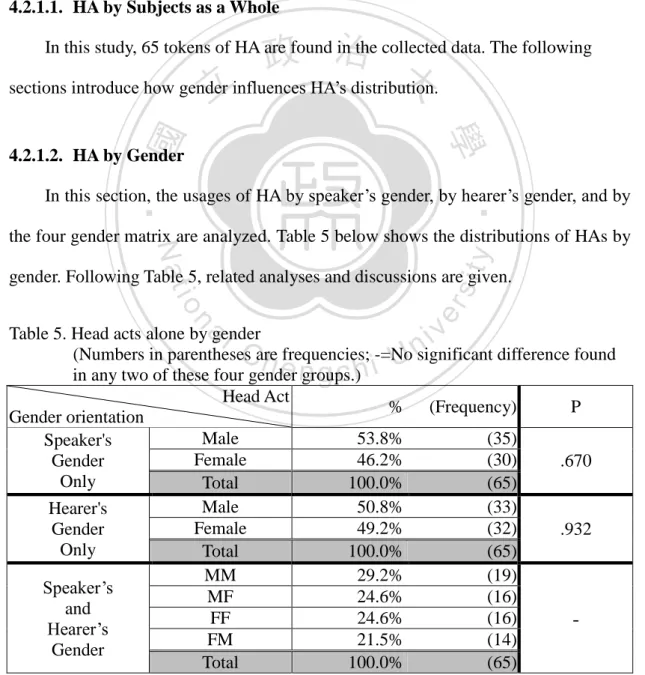

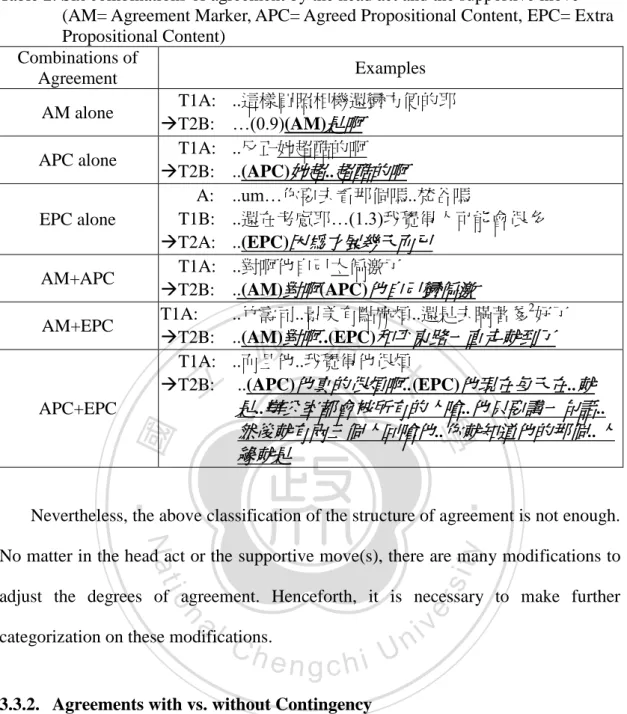

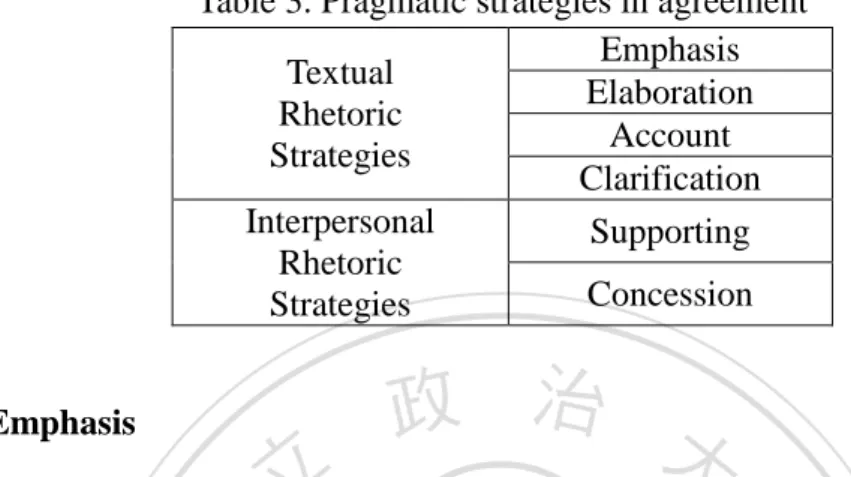

(6) Chapter 3 Methodology ............................................................................................. 23 3.1. Data Collection ............................................................................................. 23 3.1.1. Data Resource .................................................................................. 23 3.1.2. Social Distribution of Subjects ........................................................ 24 3.2. Procedures of Data Analysis ......................................................................... 24 3.3. Classification of Agreement ......................................................................... 24 3.3.1. The Structure of Agreement ............................................................. 25 3.3.2. Agreements with vs. without Contingency ...................................... 27 3.3.2.1. Upgrading Agreement ....................................................... 28 3.3.2.2. Preserving Agreement ....................................................... 29 3.3.2.3. Downgrading Agreement .................................................. 30 3.4. Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement............................................................... 31 3.4.1. Emphasis .......................................................................................... 32. 政 治 大. Elaboration ....................................................................................... 32 Account ............................................................................................ 33 Clarification ..................................................................................... 34 Supporting ........................................................................................ 35 Concession ....................................................................................... 35. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 3.4.2. 3.4.3. 3.4.4. 3.4.5. 3.4.6.. sit. y. Nat. Chapter 4 Data Analysis (1): Constructions of Agreement .................................... 37. n. al. er. io. 4.1. Agreement Tokens as a Whole ..................................................................... 37 4.1.1. Agreement Tokens as a Whole by Gender ....................................... 37 4.1.1.1. Agreement Tokens as a Whole by Speaker’s Gender ........ 38 4.1.1.2. Agreement Tokens as a Whole by Hearer’s Gender .......... 38 4.1.1.3. Agreement Tokens as a Whole by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ........................... 39. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 4.2. Categories of Agreement .............................................................................. 39 4.2.1. HA (Head Act Alone) ....................................................................... 40 4.2.1.1. HA by Subjects as a Whole ............................................... 40 4.2.1.2. HA by Gender .................................................................... 40 4.2.1.2.1. HA by Speaker’s Gender ................................. 41 4.2.1.2.2. HA by Hearer’s Gender ................................... 41 4.2.1.2.3. HA by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ... 41 4.2.2. SM (Supportive Moves Alone) ........................................................ 42 4.2.2.1. SM by Subjects as a Whole ............................................... 42 4.2.2.2. SM by Gender ................................................................... 42 4.2.2.2.1. SM by Speaker’s Gender ................................. 42 vi.

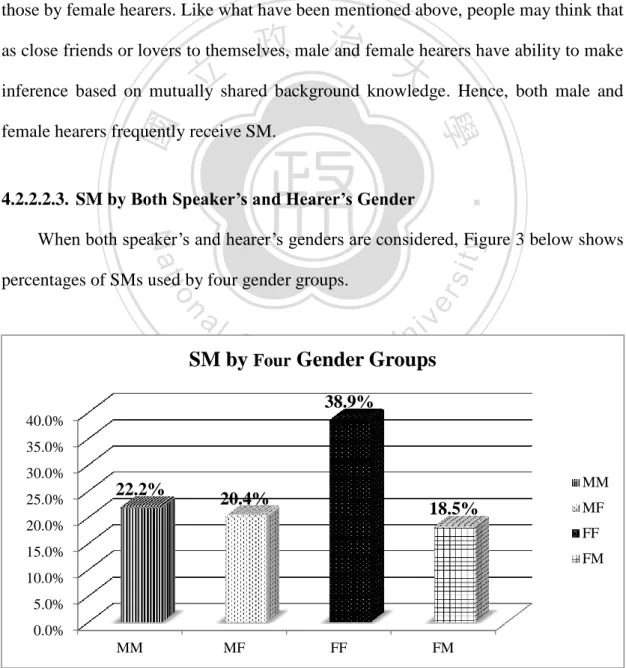

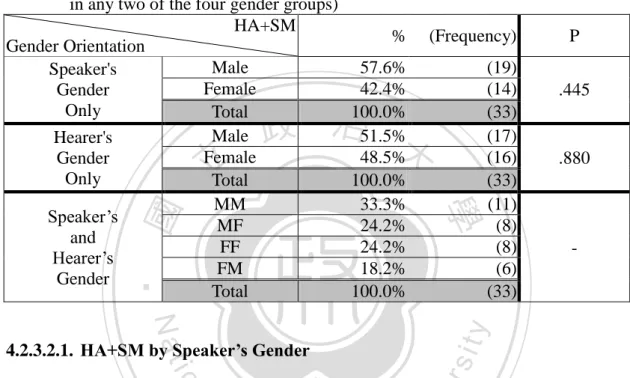

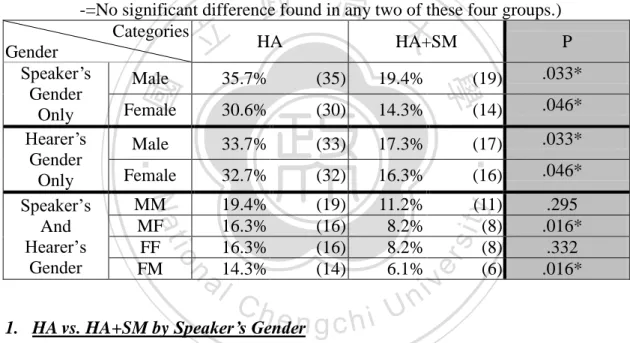

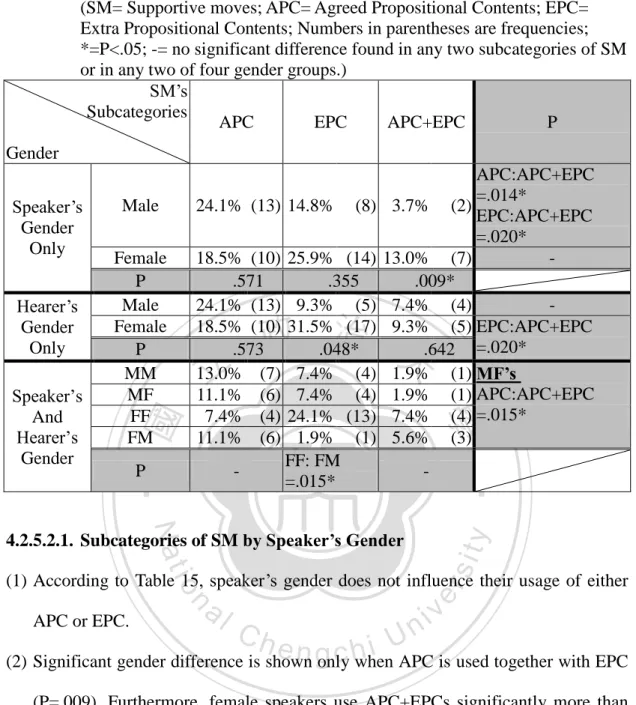

(7) 4.2.2.2.2. SM by Hearer’s Gender ................................... 43 4.2.2.2.3. SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ... 43 4.2.3. HA+SM (Head Act with Supportive Moves)................................... 44 4.2.3.1. HA+SM by Subjects as a Whole ....................................... 44 4.2.3.2. HA+SM by Gender ........................................................... 45 4.2.3.2.1. HA+SM by Speaker’s Gender ......................... 45 4.2.3.2.2. HA+SM by Hearer’s Gender ........................... 45 4.2.3.2.3. HA+SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender.............................................................. 46 4.2.4. HA vs. SM vs. HA+SM (Head Act alone vs. Supportive Moves Alone vs. Head Act with Supportive Moves) .................................. 46 4.2.4.1. HA vs. SM ......................................................................... 46 4.2.4.1.1. HA vs. SM by Subjects as a Whole ................. 47 4.2.4.1.2. HA vs. SM by Gender ...................................... 48. 立. 政 治 大 1. HA vs. SM by Speaker’s Gender .................. 48. ‧ 國. 學. 2. HA vs. SM by Hearer’s Gender .................... 49 3. HA vs. SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ........................................... 49. ‧. 4.2.4.2. HA vs. HA+SM ................................................................. 50 4.2.4.2.1. HA vs. HA+SM by Subjects as a Whole ......... 50 4.2.4.2.2. HA vs. HA+SM by Gender .............................. 51 1. HA vs. HA+SM by Speaker’s Gender .......... 51 2. HA vs. HA+SM by Hearer’s Gender ............ 51 3. HA vs. HA+SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ........................................... 52 4.2.4.3. SM vs. HA+SM ................................................................. 52 4.2.4.3.1. SM vs. HA+SM by Subjects as a Whole ......... 53 4.2.4.3.2. SM vs. HA+SM by Gender ............................. 53. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 1. SM vs. HA+SM by Speaker’s Gender .......... 54 2. SM vs. HA+SM by Hearer’s Gender ............ 54 3. SM vs. HA+SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ........................................... 55 4.2.5. Subcategories of SM (Supportive Moves) ....................................... 55 4.2.5.1. Subcategories of SM by Subjects as a Whole ................... 55 4.2.5.2. Subcategories of SM by Gender ........................................ 56 4.2.5.2.1. Subcategories of SM by Speaker’s Gender ..... 57 4.2.5.2.2. Subcategories of SM by Hearer’s Gender ....... 58. vii.

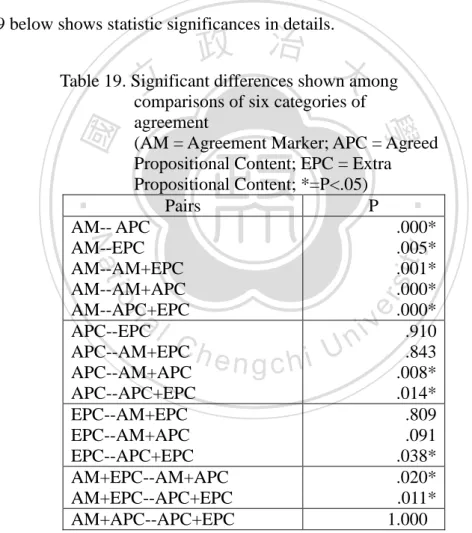

(8) 4.2.5.2.3. Subcategories of SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ........................................ 59 4.2.6. Subcategories of HA+SM (Head Act with Supportive Moves) ....... 59 4.2.6.1. Subcategories of HA+SM by Subjects as a Whole ........... 60 4.2.6.2. Subcategories of HA+SM by Gender ................................ 61 4.2.7. All Six Subcategories of Agreement ................................................ 61 4.2.7.1. All Six Subcategories of Agreement by Subjects as a Whole ..................................................... 62 4.2.7.2. All Six Subcategories of Agreement by Gender ............... 63 4.2.7.2.1. All Six Subcategories of Agreement by Speaker’s Gender ........................................ 64 4.2.7.2.2. All Six Subcategories of Agreement by Hearer’s Gender .......................................... 65 4.2.7.2.3. All Six Subcategories of Agreement. 立. 政 治 大 by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender .......... 66. ‧ 國. 學. 4.2.8. Summary of 4.2. ............................................................................... 67 4.3. Degrees of Agreement .................................................................................. 70 4.3.1. Agreement by Degrees ..................................................................... 71. ‧. 4.3.1.1. Agreement by Degrees with Subjects as a Whole ............. 71 4.3.1.2. Impacts of Gender on Agreement by Degrees ................... 73 4.3.1.2.1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on Agreement by Degrees ....................................................... 75 4.3.1.2.2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on Agreement by Degrees ....................................................... 75 4.3.1.2.3. Impacts of Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender on Agreement by Degrees ................... 76 4.3.2. HA (Head Act Alone) by Degrees .................................................... 78 4.3.2.1. HA by Degrees with Subjects as a Whole ......................... 78. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 4.3.2.2. Impacts of Gender on HA by Degrees ............................... 79 4.3.2.2.1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on HA by Degrees ....................................................... 81 4.3.2.2.2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on HA by Degrees ....................................................... 81 4.3.2.2.3. Impacts of Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender on HA by Degrees ................ 82 4.3.3. SM (Supportive Moves Alone) by Degrees ..................................... 83 4.3.3.1. SM by Degrees with Subjects as a Whole ......................... 83 4.3.3.2. Impacts of Gender on SM by Degrees .............................. 84. viii.

(9) 4.3.3.2.1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on SM by Degrees ....................................................... 86 4.3.3.2.2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on SM by Degrees ....................................................... 86 4.3.3.2.3. Impacts of Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender on SM by Degrees ................ 86 4.3.4. HA+SM (Head Act with Supportive Moves) by Degrees ............... 87 4.3.4.1. HA+SM by Degrees with Subjects as a Whole ................. 87 4.3.4.2. Impacts of Gender on HA+SM by Degrees ...................... 88 4.3.4.2.1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on HA+SM by Degrees ................................... 90 4.3.4.2.2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on HA+SM by Degrees ................................... 90 4.3.5. HA vs. SM vs. HA+SM (Head Act vs. Supportive Moves. 政 治 大 vs. Head Act with Supportive Moves) by Degrees .......................... 90 立 4.3.5.1. HA vs. SM by Degrees ...................................................... 91. ‧ 國. 學. 4.3.5.1.1. HA vs. SM by Degrees with Subjects as a Whole............................................................... 91. ‧. 4.3.5.1.2. Impacts of Gender on HA vs. SM by Degrees ....................................................... 92 1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on HA vs. SM by Degrees ............................................. 94 2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on HA vs. SM by Degrees ............................................. 95 3. Impacts of Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender on HA vs. SM by Degrees ................ 95 4.3.5.2. HA vs. HA+SM by Degrees .............................................. 96 4.3.5.2.1. HA vs. HA+SM by Degrees. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. with Subjects as a Whole ................................. 97 4.3.5.2.2. Impacts of Gender on HA vs. HA+SM by Degrees ....................................................... 98 1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on HA vs. HA+SM by Degrees ................... 100 2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on HA vs. HA+SM by Degrees ................... 101 4.3.5.3. SM vs. HA+SM by Degrees ............................................ 101 4.3.5.3.1. SM vs. HA+SM by Degrees with Subjects as a Whole ............................... 101. ix.

(10) 4.3.5.3.2. Impacts of Gender on SM vs. HA+SM by Degrees ..................................................... 102 1. Impacts of Speaker’s Gender on SM vs. HA+SM by Degrees................... 105 2. Impacts of Hearer’s Gender on SM vs. HA+SM by Degrees................... 105 4.3.6. All Six Subcategories of Agreement by Degrees ........................... 106 4.3.7. Summary of 4.3. ............................................................................. 109 Chapter 5 Data Analysis (2): Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement ................... 111 5.1. Amounts of Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement ......................................... 111 5.1.1. Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement with Subjects as a Whole ............................................................... 111. 政 治 大. 5.1.2. Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement by Gender .............................. 113 5.1.2.1. Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement by Speaker’s Gender ....................................................... 115 5.1.2.2. Pragmatic Strategy in Agreement by Hearer’s Gender ......................................................... 116. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 5.1.2.3. Pragmatic Strategy in Agreement by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ......................... 117 5.2. Pragmatic Strategies in HA (Head Act Alone) ........................................... 117 5.2.1. Pragmatic Strategies in HA by Subjects as a Whole...................... 118 5.2.2. Pragmatic Strategies in HA by Gender .......................................... 119 5.3. Pragmatic Strategies in SM (Supportive Moves Alone)............................. 121 5.3.1. Pragmatic Strategies in SM by Subjects as a Whole ..................... 121 5.3.2. Pragmatic Strategies in SM by Gender .......................................... 123 5.4. Pragmatic Strategies in HA+SM (Head Act with Supportive Moves) ....... 125. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 5.4.1. Pragmatic Strategies in HA+SM by Subjects as a Whole ............. 125 5.4.2. Pragmatic Strategies in HA+SM by Gender .................................. 127 5.4.2.1. Pragmatic Strategies in HA+SM by Speaker’s Gender ....................................................... 127 5.4.2.2. Pragmatic Strategies in HA+SM by Hearer’s Gender ......................................................... 128 5.4.2.3. Pragmatic Strategies in HA+SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ......................... 129 5.5. Pragmatic Strategies in the Subcategories of SM (Supportive Moves) .................................................................................... 131. x.

(11) 5.5.1. Pragmatic Strategies in the Subcategories of SM by Subjects as a Whole .................................................................. 131 5.5.2. Pragmatic Strategies in the Subcategories of SM by Gender ....................................................................................... 133 5.5.2.1. Pragmatic Strategies in the Subcategories of SM by Speaker’s Gender ....................................................... 134 5.5.2.2. Pragmatic Strategies in the Subcategories of SM by Hearer’s Gender ......................................................... 137 5.5.2.3. Pragmatic Strategies in the Subcategories of SM by Both Speaker’s and Hearer’s Gender ......................... 139 5.6. Pragmatic Strategies in All Six Subcategories of Agreement..................... 141 5.7. Summary of Pragmatic Strategies in Agreement. ....................................... 144. 政 治 大. Chapter 6 Conclusion .............................................................................................. 148. 立. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 6.1. Summary of the Major Findings ................................................................. 148 6.1.1. Agreement in General .................................................................... 148 6.1.2. Agreement by Gender .................................................................... 150 6.2. Limitations and Suggestions....................................................................... 153. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. References ................................................................................................................. 155. Ch. engchi. xi. i Un. v.

(12) LIST OF TABLES. Table 1. Correlations of content and format in adjacency pair seconds ...................... 13 Table 2. Six combinations of agreement by the head act and the supportive move .... 27 Table 3. Pragmatic strategies in agreement.................................................................. 32 Table 4. Agreement tokens as a whole by gender ........................................................ 38 Table 5. Head acts alone by gender ............................................................................. 40 Table 6. Supportive moves alone by gender ................................................................ 42 Table 7. Head act with supportive moves by gender ................................................... 45. 政 治 大. Table 8. Comparisons between head act alone and supportive moves alone............... 47. 立. Table 9. Head act alone and supportive moves alone by gender ................................. 48. ‧ 國. 學. Table 10. Head act with supportive moves versus head act without supportive moves .................................................. 50. ‧. Table 11. Head act with supportive moves versus head act without supportive moves by gender.................................. 51. y. Nat. sit. al. er. io. Table 12. Comparisons between supportive moves with head act and supportive movess without head act ............................... 53. v. n. Table 13. Supportive moves with head act versus supportive moves alone by gender...................................................................................................... 54. Ch. engchi. i Un. Table 14. Comparisons among different subcategories of supportive moves.............. 55 Table 15. Subcategories of supportive moves by gender ............................................. 57 Table 16. Subcategories of head act with supportive moves ....................................... 60 Table 17. Subcategories of Head act with supportive moves by gender ..................... 61 Table 18. All six subcategories of agreement .............................................................. 62 Table 19. Significant differences shown among comparisons of six categories of agreement.......................................................................... 62 Table 20. Inventory of agreement categories by speaker’s gender versus by hearer’s gender............................................................................. 64 Table 21. Significant differences among categories of agreement by speaker’s gender...................................................................................... 65 xii.

(13) Table 22. Significant differences among categories of agreement by hearer’s gender ........................................................................................ 66 Table 23. Significant differences among categories of agreement by both speaker’s and hearer’s genders ....................................................... 67 Table 24. Agreement by degrees .................................................................................. 71 Table 25. Subtypes of mixed agreement ...................................................................... 72 Table 26. Agreement by degrees by gender ................................................................. 74 Table 27. Head act with subjects as a whole by degrees ............................................. 78 Table 28. Head act alone with degrees by gender ........................................................ 80 Table 29. Supportive moves alone with subjects as a whole by degrees ..................... 83. 政 治 大 Table 31. Head act with supportive moves by degrees ................................................ 87 立 Table 30. Supportive moves alone with degrees by gender ......................................... 85. Table 32. Head act with supportive moves with degrees by gender ............................ 89. ‧ 國. 學. Table 33. Head act alone versus supportive moves alone with degrees ...................... 91. ‧. Table 34. Head act alone versus supportive moves alone with degrees by gender...................................................................................................... 93. Nat. er. io. sit. y. Table 35. Head act with supportive moves versus head act without supportive moves with degrees ............................. 97 Table 36. Head act with supportive moves versus head act without supportive moves with degrees by speaker’s gender and by hearer’s gender ................................................ 99. n. al. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Table 37. Supportive moves with head act vs. supportive moves alone with degrees ............................................................................................... 102 Table 38.Supportive moves with head act versus supportive moves alone with degrees by speaker’s gender and by hearer’s gender ......................... 104 Table 39. Inventory of agreement categories with degrees ........................................ 107 Table 40. Pragmatic strategies in agreement by subjects as a whole ......................... 112 Table 41. Pragmatic strategies in agreement by gender ............................................. 114 Table 42. Pragmatic strategies in head act alone ....................................................... 118 Table 43. Pragmatic strategies in head act alone by speaker’s gender ...................... 120 Table 44. Pragmatic strategies in supportive moves .................................................. 121 xiii.

(14) Table 45. Pragmatic strategies in supportive moves by gender ................................. 124 Table 46. Pragmatic strategies in head act with supportive moves ............................ 126 Table 47. Pragmatic strategies in head act with supportive moves by speaker’s gender.................................................................................... 127 Table 48. Pragmatic strategies in head act with supportive moves by hearer’s gender ...................................................................................... 128 Table 49. Pragmatic strategies in head act with supportive moves by both speaker’s and hearer’s genders ..................................................... 130 Table 50. Pragmatic strategies in the subcategories of supportive moves ................. 132 Table 51. Pragmatic strategies in the subcategories of supportive moves by speaker’s gender.................................................................................... 135. 政 治 大 by hearer’s gender 立...................................................................................... 138. Table 52. Pragmatic strategies in the subcategories of supportive moves. ‧ 國. 學. Table 53. Pragmatic strategies in the subcategories of supportive moves by both speaker’s and hearer’s genders ..................................................... 140. ‧. Table 54. Pragmatic strategies in all six subcategories of agreement ........................ 143. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiv. i Un. v.

(15) LIST OF FIGURES. Figure 1. Possible strategies of dealing with FTAs ...................................................... 10 Figure 2. Decision tree of agreement ........................................................................... 28 Figure 3. Percentages of supportive moves by both speaker’s and hearer’s gender ......................................................... 43 Figure 4. Comparisons between WOC and WC by both speaker’s and hearer’s gender ......................................................... 76 Figure 5. Comparisons between upgrading agreement and preserving agreement by both speaker’s and hearer’s gender ......................................................... 77. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xv. i Un. v.

(16) LIST OF ABBRIVIATIONS. Gender M = Male F = Female Roles in Conversation S = Speaker H = Hearer. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 立. 學. Interlocutors by Gender MM = Male Speaker and Male Hearer MF = Male Speaker and Female Hearer FF = Female Speaker and Female Hearer FM = Female Speaker and Male Hearer. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. The Structure of Agreement HA = Head Act alone SM = Supportive Moves alone HA+SM = Head Act with Supportive Moves AM = Agreement Marker APC = Agreed Propositional Content EPC = Extra Propositional Content AM+APC = Agreement Marker with Agreed Propositional Content AM+EPC = Agreement Marker with Extra Propositional Content. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. APC+EPC = Agreed Propositional Content with Extra Propositional Content Modification of Agreement WOC = Without Contingency WC = With Contingency Up = Upgrading Ps = Preserving Dw = Downgrading. xvi.

(17) Pragmatic Strategies of Agreement TRS = Textual Rhetoric Strategies IRS = Interpersonal Rhetoric Strategies EMP = Emphasis ELA = Elaboration ACC = Account CLAR = Clarification SUP = Supporting CONC = Concession. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xvii. i Un. v.

(18) 國 立 政 治 大 學 語 言 學 研 究 所 碩 士 論 文 提 要 研究所別:語言學研究所 論文名稱:中文對話中的同意使用:語用學與社會語言學分析 指導教授:詹惠珍 博士 研究生:魏愷玟 論文提要內容:(共一冊,共六章) 本論文分析中文使用者如何選擇同意行為中相關之同意類別、同意程度、和. 治 政 語用策略。此外,本研究也檢視性別對人們同意使用的影響力。本論文採用言談 大 立 分析(conversational analysis)作為研究框架。除此之外,本研究以言語行為理論 ‧ 國. 學. (speech act theory),合作原則(Cooperative Principles)及禮貌原則理論(Politeness. ‧. Principles)作為理論基礎。. sit. y. Nat. 本篇論文調查八個雙人面對面的日常會話,其中同性別的會話共四份(包含. io. er. 男生和男生的會話兩份,以及女生和女生的會話兩份),跨性別之間的會話共四 份。在這八段會話當中,總共找到 152 筆語料。在分析的過程中,先將同意的語. al. n. iv n C 料做分類,進而分析同意的類別、程度、語用策略的使用、社會因素(性別),以 hengchi U 及這四者之間的互動。 研究結果顯示,(一)同意類別方面,人們使用同意核心(Head act alone) 和同意修飾語(Supportive moves alone)的頻率皆高於同意核心和修飾語的併用; (二)六個同意支類別方面,同意表徵(Agreement marker)使用頻率顯著高於 其他五個同意支類別;(三)同意的強度方面,無條件同意(Agreement without contingency)的使用率顯著高於有條件同意(Agreement with contingency) ; (四) 無條件同意的支類別方面,強化同意(Upgrading agreement)的使用率顯著高於 持平同意(Preserving agreement); (五)語用策略方面,篇章修辭策略(Textual rhetoric strategies)的使用率顯著高於人際修辭策略(Interpersonal rhetoric xviii.

(19) strategies); (六)篇章修辭策略的支類別方面,強調策略(Emphasis)和闡述策 略(Elaboration)是最常被使用的;(七)修飾語的支類別和篇章修辭策略的互 動方面,研究結果發現一項語用策略分工:強調策略通常使用於受同意的命題內 容(Agreed propositional content) ,而闡述策略通常使用於新增的命題內容(Extra propositional content);(八)人際修辭策略方面,研究結果也發現一項語用策略 分工:讓步策略(Concession)通常使用於同意核心,而支持策略(Supporting) 通常使用於同意修飾語;(九)最後,研究結果顯示性別會影響人們的同意使用 情形。特別是女性容易在同意類別、同意強度和語用策略的使用上,受到聽話者 的性別的影響。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xix. i Un. v.

(20) Abstract. This thesis investigates people’s choice among categories of agreement construction, degrees of agreement, and pragmatic strategies in agreement. Also, the influence of gender is examined. Conversational analysis (CA) is taken as the framework of this thesis. Besides, speech act theory (Austin, 1962; Searle, 1975), Cooperative Principle (Grice, 1975), and Politeness Principles (Brown and Levinson,. 治 政 1978, 1987; Leech, 1983) are theoretical foundations of 大this study. 立 8 face-to-face conversations, including 4 same-gender groups and 4 cross-gender ‧ 國. 學. groups, which yield 152 tokens of agreement, were investigated. Related data are. ‧. classified and analyzed by categories of agreement, degrees of agreement, and. sit. y. Nat. pragmatic strategies in agreement, social factor—gender in this study, and the. io. er. interaction among the four.. al. The results of quantitative analyses confirm the following findings. (1) For. n. iv n C categories of agreement, people apply head act alone and supportive move alone h eboth ngchi U more frequently than head act with supportive moves. (2) For the six subcategories of agreement, agreement marker overrides the other five. (3) For degrees of agreement, agreement without contingency emerges much more frequently than agreement with contingency. (4) For the subtypes of agreement without contingency, upgrading agreement is used significantly more than preserving agreement. (5) For pragmatic strategies, textual rhetoric strategies are applied much more frequently than interpersonal rhetoric strategies. (6) In textual rhetoric strategies, emphasis and elaboration are adopted most of the time. (7) For the interaction of subtypes of supportive moves and textual rhetoric strategies, a division of pragmatic labor xx.

(21) emerges: emphasis often occurs in agreed propositional content, while elaboration often occurs in extra propositional content. (8) For interpersonal rhetoric strategies, a division of pragmatic labor is also located: concession often appears in head act alone, whereas supporting often appears in supportive moves alone. Lastly, (9) Gender is an influential factor in the use of agreement. Women are the one who tend to be influenced by hearer’s gender in their choice of categories of agreement, degree of agreement, and pragmatic strategies in agreement.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xxi. i Un. v.

(22) Chapter 1 Introduction. 1.1. Background of the Study Agreement—as a response to other people’s opinion toward a person, an object, or an event—is common in daily conversation. Studies on agreement have received attention from many disciplines, including anthropology, psychology, linguistics, and language teaching. Agreement is often characterized as affiliating, preferred and. 政 治 大 that seeking agreement is one of the strategies to secure positive face in order to gain 立 unmarked action (Pomerantz 1984; Sacks 1987). Brown and Levinson (1987) suggest. ‧ 國. 學. “common ground” with his/her hearer. Moreover, by agreeing, the speaker satisfies the hearer’s desire to be “right” and fulfills the purpose of coming closer to the hearer. ‧. (Kuo, 1994). In the study of gender differences, Tannen (1990) proposed that agreeing. Nat. sit. y. and being the same with other people are the ways to create rapport for girls. In other. n. al. er. io. words, why agreement is favored stems from fulfilling the hearer’s positive face.. 1.2.The Problem. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Many of the previous studies have investigated the ways to arrange message components of agreement and their related linguistic devices, but there are still gaps waiting to be bridged. First, the encoding of agreement may not be as simple as some scholars propose. Pomerantz (1984) suggests that agreements can be divided into upgrading agreement, agreements with same evaluation, and downgrading agreement. Blum- Kulka et al. (1989) indicate that agreement may compose of a head act and/or supportive moves, which include agreement markers and/or elaboration of the agreed propositional contents. However, no studies specifically aim at the interaction of what Pomerantz and Blum- Kulka et al. propose. Second, most of the studies have 1.

(23) concentrated on analyzing the linguistic forms of agreement, leaving pragmatic strategies of agreement unexamined. Third, the influence of social factors, such as gender, on the construction of agreement has long been ignored. Although women’s social status has been raised in the modern era, Chinese society has long been patriarchal in the history; therefore, the impacts of gender on Chinese speakers’ verbal performance (in this case, agreement) deserve closer examination.. 1.3. Research Questions and Hypotheses Based on the problems given above, three research questions are to be answered in this study.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. (1) Categories of Agreement. Question A: Among the three categories of agreement content structure (namely,. ‧. head act alone HA, supportive move alone SM, and head act with. sit. y. Nat. supportive move HA+SM), which type is more preferred by. io. er. Mandarin speakers?. al. n. Hypothesis A-1: Head act alone (HA) would occur more frequently than. C halone (SM). U n i supportive moves engchi. v. Hypothesis A-2: Head act alone (HA) would occur more frequently than head act with supportive move (HA+SM). Hypothesis A-3: Head act with supportive moves (HA+SM) emerges more frequently than supportive move alone (SM). (2) Degrees of Agreement Question B: Among the various kinds of agreement by degrees, which one is used more frequently, agreement without contingency ( including upgrading and preserving agreement) or agreement with contingency (i.e. downgrading agreement)? 2.

(24) Hypothesis B-1: Agreement without contingency (WOC) would occur more frequently than agreement with contingency (WC). Hypothesis B-2: Upgrading agreement is applied more frequently than preserving agreement. (3) The Impact of Gender Question C: Is gender an influential factor to the construction of agreement? If yes, how does it determine a Mandarin speaker’s choice of pragmatic strategies of agreement? Question C-1: Is speaker’s gender an influential factor to the construction of agreement?. 立. 政 治 大. Hypothesis C-1: Speaker’s gender is a significant factor to manipulate the. ‧ 國. 學. construction and pragmatic strategies in the performance of. ‧. agreement.. sit. y. Nat. Question C-2: Is hearer’s gender an influential factor to the construction of. io. er. agreement?. Hypothesis C-2: Hearer’s gender is a significant factor to influence people’s. al. n. iv n C construction and pragmatic in agreement. h e n gstrategies chi U. Question C-3: When both speaker’s and hearer’s genders are considered, is gender an influential factor to the construction of agreement? Hypothesis C-3: When both speaker’s and hearer’s genders are considered, gender is a significant factor to manipulate the construction and pragmatic strategies in the performance of agreement.. 1.4. Organization of This Thesis This thesis is composed by six chapters: Chapter 1 introduces the purpose of this study and its hypotheses; Chapter 2 reviews related theories and studies on agreement; 3.

(25) Chapter 3 presents the resources of data as well as the methodology of examining the conversations; Chapter 4 presents data analyses and findings in construction of agreement; Chapter 5 discusses data results of pragmatic strategies in agreement; Chapter 6 makes the conclusion, limitation and suggestion of this study.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 4. i Un. v.

(26) Chapter 2 Literature Review. In this chapter, theories and previous studies related to agreement are reviewed, including speech act theory, indirectness of speech, conversational structure, and pragmatic and social principles.. 2.1. Speech Act Theory Agreement as a speech act can be expressed directly and indirectly, which could. 治 政 influence the force of agreement. Thus, it is inevitable 大 to review speech act theory and 立 indirect speech act. ‧ 國. 學. A speech act is a functional unit in communication which means people do. ‧. something by saying something. The concept of speech act begins from Austin’s. sit. y. Nat. (1962) How to Do Things with Words, which is later discussed and expanded by many. io. er. scholars, especially by Searle (1969). Austin observes that under the appropriate. al. circumstances, the words people uttered are not merely about the referential content. n. iv n C of sentences, but also performinghparticular actionsUwhich aim at influencing the engchi hearer simultaneously. For example, when a priest announces “I pronounce you. husband and wife” to a wedding couple, he is doing the act of pronouncing. After these utterances are pronounced, the wedding couple has a new social relationship. Austin terms the utterances of this type “Performative,” in contrast with “Constatives” which is used to denote the utterances that are employed for saying something but not doing something. Considering the vague distinction between performative and constatives, Austin (1962) further brings out three essential components in speech act. According to Austin, utterances have three layers of actions: locutionary act, illocutionary act and 5.

(27) perlocutionary act. Locutinary act represents an act with a meaningful linguistic expression. Illocutionary act as Austin’s central innovation carries the purposes or functions in the speaker’s intention. It is performed by the conventional forces associated with them. Perlocutionary force denotes the result of effect which is produced by the context, whether intended or not. It means that in different socio-cultural contexts, the same utterances can derive various illocutionary forces. As a follower of Austin, Searle (1975) classifies illocutionary acts into the following five kinds, namely, representatives, directives, commissives, expressives and declarations. Nevertheless, the knowledge of speech act alone is not enough for the hearer to. 治 政 decode the speaker’s intention successfully because 大 the speaker’s meaning and the 立 sentence meaning usually come apart (Searle, 1975). It means that the speaker’s true ‧ 國. 學. intention can be conveyed indirectly. According to Searle (1975), indirect speech act. ‧. is that kind of illocutionary act that is performed by way of performing another act. In. sit. y. Nat. other words, indirect speech act is composed by two illocutionary acts: one Primary. io. al. illocutionary act, which contributes literal meaning.. er. illocutionary act, which confers speaker’s intention, in combination with a Secondary. n. iv n C For the hearer to decode indirect acts, Searle further brings up four kinds h espeech ngchi U. of knowledge which are necessary. They are the theory of speech act, the Cooperative Principle (which is reviewed below), mutually shared factual background information and the ability of making inferences.. 2.2. The Cooperative Principle As indicated above, speech act theory is not the only background knowledge for the hearer to attain the message the speaker wants to send. Conversationalists assume that there should be a universal set of rule to guide how people communicate with each other (Levinson, 1983; Brown and Levinson, 1987). One principle is the 6.

(28) Cooperative Principle (CP) proffered by Grice (1975). Following this principle, the speaker shapes their utterances and the hearer interprets the speaker’s utterances, effectively and efficiently. The four maxims of CP and examples are given below.. 1.. Maxim of Quality: Inaccurate messages and information without adequate evidences should not be conveyed. For instance, without the knowledge of where to go, people should not direct a stray to a wrong place to prevent from telling something false.. 2.. Maxims of Quantity:. 政 治 大. In communication, the speaker should give as much information as needed, but. 立. no more than what is needed. For example, if people are asked for direction, it. ‧ 國. 學. doesn’t mean that they need to tell others the details about how to go to a place, because the quantity is too much, if they do so.. ‧. 3.. Maxim of Relevance:. y. Nat. sit. The speech given by the interlocutors should be relevant to the topic of the. n. al. er. io. communication. For example, when Speaker A says, “I want to buy a drink,” and. i Un. v. Speaker B replies, “Around the corner, there is a Seven-eleven,” it is expected. Ch. engchi. that beverages are available in that Seven-eleven. 4.. Maxim of Manner: The speaker’s speech should be orderly, brief and without obscurity or ambiguity. For instance, a story should be told chronologically because orderly arrangement makes the story more understandable. (Adaptation from Leech, 1983) Although different societies or cultures do not use the above maxims in the same. way, CP can be seen as an “‘unmarked’ and social neutral presumptive” structure of conversation (Brown and Levionson, 1987:5). Interlocutors, both the speaker and the 7.

(29) hearer, would naturally abide by the principle in order to converse with each other in an efficient, rational, and co-operative way. Moreover, Horn (1984) further proposes the Principle of Least Effort (and the Principle of Sufficient Effort) to revise Grice’s Cooperative Principle. He suggests that CP can be reduced into two principles: The first one is the Q Principle-Make your contribution sufficient, and R Principle-Make your contribution necessary. From the works of Tannen (1975, 1979) mentioned in Horn (1984: 16), there is a tendency that female obeys the Q Principle more, while male obeys the R Principle more. In other words, female is considered more hearer-oriented, while male is considered more speaker-oriented.. 立. 政 治 大. However, in real conversation, Grice’s Cooperative Principle is often found. ‧ 國. 學. violated or flouted. People would rather take a risk of causing communication to fail. ‧. down and break the rules which are universally known. It means that these principles. sit. y. Nat. mentioned above are still not enough to explain how people communicate with each. io. n. al. er. other. Politeness Principle (PP) can be one of the probable explanations.. 2.3. Politeness Principles. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. When people proffer agreement, the most efficient and effort-saving way is to utter a word, “yes” or “right.” Nevertheless, in daily conversation, the agreeing party, not afraid of being considered flattering, usually adds similar experiences or gives a justification to strengthen their agreement. It means that people would rather violate CP (Quantity in this example) for politeness’ sake. Leech (1983) suggests that when CP enables the speakers to communicate which is based on the assumption that all the interlocutors are cooperative, Grice overlooks the role of politeness in the social interactions. According to Leech (1983), being polite in words not only establishes and keeps “comity” among people, but also helps the interlocutors engaged in a 8.

(30) harmonious social interaction. When it comes to agreement, Brown and Levinson (1987) propose that agreement is a way to seek positive politeness because by agreeing, the speaker can claim common ground with the hearer. Therefore, briefly reviewing theories of politeness is necessary when conducting the analysis of agreement. The following paragraphs are about some major studies on politeness.. 2.3.1. Politeness Principle by Lakoff (1973) Lakoff (1973, 1975, 1977) is the first scholar to consider politeness from the conversational-maxim point of view. She suggests two rules of Pragmatic. 政 治 大. Competence: Be clear and Be polite. The first rule covers the maxims of the Gricean. 立. CP, while the second rule consists of three sub-rules: (a) don’t impose (distance), (b). ‧ 國. 學. give option (deference), and (c) be friendly (camaraderie). Lakoff (1979) further claims that these politeness rules are not in a hierarchical relationship but are points. ‧. on a continuum scale, with one end stood by the Gricean CP and the other end,. y. Nat. io. sit. camaraderie. People from different cultures have different priority among these rules. n. al. er. which could cause stylistic differences or even communication breakdown.. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 2.3.2. Politeness Principle by Brown and Levinson (1978) Brown and Levinson’s (1978, 1987) politeness theory is derived from Goffman’s (1967) notion of face. They propose that face, emotionally invested, is something that people can lose, maintain or enhance. In conversation, people cooperate with each other in order to maintain face in interaction. Brown and Levinson (1987: 61) further suggest that every individual has two faces: negative face and positive face. Negative face means the desire for freedom of action and freedom from being imposed, while positive face means the eager to be complimented and approved of in social interaction. Based on the concept of face, they find the intrinsic nature of the. 9.

(31) addressee’s and the speaker’s face wants runs contradictory with each other. The contradiction inspires them the face-threatening acts (FTAs) which mean acts threatening face intrinsically. Figure 1 shows five strategies for dealing with FTAs.. 1. Without redressive action, baldly on record 4. off record. Do the FTA. 5. Don’t do the FTA. with redressive action. 2. positive politeness 3. negative politeness. 政 治 大. Figure 1. Possible strategies of dealing with FTAs. 立. Among five possible responses to FTAs, positive politeness is highly related to. ‧ 國. 學. this study. According to Brown and Levinson (1987: 70), positive politeness is. ‧. oriented to the hearer’s positive face which means the positive self-image that the. sit. y. Nat. hearer claims for self. Positive politeness is “approach-based;” When focusing on. io. er. positive politeness to deal with FTAs, the speaker intends to express that he/she wants the hearer’s want. For example, the speaker would treat the hearer as a friend or. al. n. iv n C family member whose wants or personality known and liked. And agreement is h e n g are chi U one of the sub-strategies of positive politeness for the speaker to claim common ground with the hearer (Brown and Levinson, 1987: 112). Agreeing with the evaluation which the hearer has made in the previous context satisfies the hearer’s want to be “right” and to be verified in his/her opinions. Therefore, agreeing with others can be taken as a social accelerator which indicates the speaker wants to be more intimate with the hearer.. 10.

(32) 2.3.3. Politeness Principle by Leech (1983) Another powerful Politeness Principle is brought up by Leech (1983). He proposed six maxims of his Politeness Principle (PP) (1983: 132) which are summarized below. 1. TACT MAXIM (a) Minimize cost to other; (b) Maximize benefit to other 2. GENEROSITY MAXIM (a) Minimize benefit to self; (b) Maximize cost to self 3. APPROBATION MAXIM (a) Minimize dispraise of other; (b) Maximize praise of other. 政 治 大. 4. MODESTY MAXIM (a) Minimize praise of self; (b) Maximize dispraise of self. 立. ‧ 國. 學. 5. AGREEMENT MAXIM (a) Minimize disagreement between self and other (b) Maximize agreement between self and other. ‧. 6. SYMPATHY MAXIM (a) Minimize antipathy between self and other (b) Maximize sympathy between self and other. io. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. Among the six maxims, the first four are in pairs with bipolar scales, while the. Ch. i Un. v. last two deal with unipolar scales. Leech (1983: 133) further suggests that not all of. engchi. the maxims and sub-maxims are equally important. For example, Tact Maxim is more important than Generosity Maxim, while Approbation Maxim is more important than Modesty Maxim. Further, every sub-maxim (a) is more important than the sub-maxim (b). In other words, negative politeness is considered weightier than positive politeness. However, when it comes to socio-cultural differences, this unequal relationship may not be true in Chinese society. Chinese people are considered the group emphasizing both negative politeness and positive politeness. And when it comes to Agreement Maxim, the analysis of this research can provide some evidences that Chinese people use many strategies to maximize their agreement. 11.

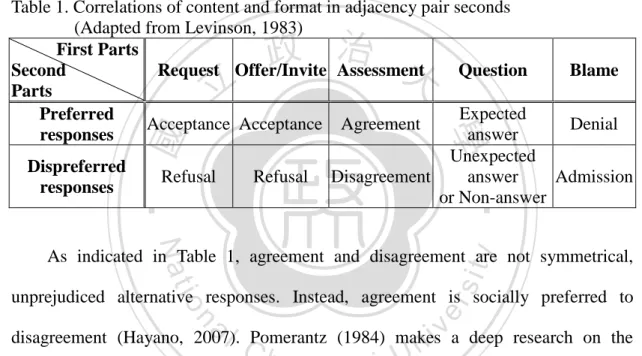

(33) Besides Agreement Maxim, the other two relevant maxims for this paper are the Tact Maxim and the Generosity Maxim. When the speaker enforces their agreement by agreement markers and supportive moves, such as account or elaboration, he or she increases cost for self and benefit for other. The speaker makes effort to talk a lot, while the hearer is benefited because of receiving more information. For politeness principles within the discussion of this study, Brown and Levinson’s face theory and Leech’s PP are taken into account because these principles are highly related to the agreement act. In addition, these two theories take both the speaker and the hearer into consideration. Lakoff’s theory focuses more on the. 治 政 speaker’s aspect so that it is excluded. 大 立 ‧ 國. 學. 2.4. Conversational Structure: Adjacency Pairs. Before the introduction of preference organization, it is inevitable to discuss the. ‧. concept of adjacency pairs first. Human conversation is not composed by random. y. Nat. sit. utterances; instead, it is systematically constructed. One of the most obvious evidence. n. al. er. io. is “adjacency pairs.” According to Schegloff and Sacks (1973), adjacency pairs are. Ch. i Un. v. sequences of two utterances which are produced by different speakers and ordered as. engchi. a “first part” and a “second part.” It means that the current speaker who proffers the first part must stop somewhere, and next speaker must produce a second part to the same pair. Some prototypical pairs are question-answer, greeting-greeting and offer-acceptance, etc. However, not all of the second parts to a first part stand equally (Levinson, 1983: 307). In other words, there is at least one preferred and one dispreferred category of response. For example, granting a request is more preferred than rejecting a request. The concept of preference is first proposed and expanded by Sacks (1973). He suggests that the preference of some responses rather than others should be taken as 12.

(34) part of the structural organization of talk. Levinson (1983:332) further demonstrates that the notion of preference is not intended as a psychological claim about speaker’s or hearer’s desires; instead, it is closely related to the linguistic concept of markedness. People try to give preferred response which is unmarked, simple and without delay, while they avoid proffering dispreferred action which is marked, complex and delayed. Levinson (1983: 336) gives the following table to illustrate some adjacency pairs with preferred and dispreferred second parts. Table 1. Correlations of content and format in adjacency pair seconds (Adapted from Levinson, 1983) First Parts Second Request Offer/Invite Assessment Question Blame Parts Expected Preferred Acceptance Acceptance Agreement Denial answer responses Unexpected Dispreferred Refusal Refusal Disagreement answer Admission responses or Non-answer. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. y. Nat. sit. As indicated in Table 1, agreement and disagreement are not symmetrical,. n. al. er. io. unprejudiced alternative responses. Instead, agreement is socially preferred to. i Un. v. disagreement (Hayano, 2007). Pomerantz (1984) makes a deep research on the. Ch. engchi. relationship between the preference organization and the structure of the turns expressing agreement as well as disagreement. Agreement/disagreement appears as the second part of the adjacency pair which is preferred or dispreferred according to the context. In a friendly talk, agreement is often as the preferred action because participants are oriented toward interpersonal coordination, and thus toward consensus (Baym, 1996). Pomerantz even terms agreement as a “preferred next action”. But when the first assessment is made to self-deprecate, agreement is as a dispreferred action because it would be interpreted as implicit criticism. When the agreement is preferred, because responses are organized to permit ‘stated. 13.

(35) disagreements to be minimized and stated agreements to be maximized,’ agreement is often stated strongly, simply and directly (Mulkay, 1985). In this study, the data of agreement as the preferred action are examined, while the data of dispreferred agreement are excluded.. 2.5. Agreement as a Speech Act In this section, agreement as a speech act would be introduced. Definition of Agreement, Speech Act Analysis of Agreement, Pragmatic Strategies and Social Constraint of Agreement, and Linguistic Features of Agreement would be presented.. 2.5.1.. 政 治 大 Definitions of Agreement 立. ‧ 國. 學. Although many studies have discussed about the construction of agreement, few of them make definition of agreement (Pomerantz, 1984; Hornero et al., 2008).. ‧. According to Cambridge Dictionary (2011), agreement occurs “when people have the. sit. y. Nat. same opinion, or when they approve of or accept something.” It means that when an. n. al. er. io. agreement is made, two parties, who view the same referent in the same way, are. i Un. v. needed. Pomerantz (1984) suggests that when a recipient agrees with the prior. Ch. engchi. assessment, he or she shows his or her assessment which focuses on the same referent and the viewpoint is consistent with the first assessment. Hornero et al. (2008) adopts Tsui’s (1994) studies and defines agreement from the structure of discourse acts. Hornero et al. claim that agreement is a response produced after assessings, reports, elicitation of agreement as well as confirmation, and before follow-ups, such as endorsement, concession and acknowledgement. It means that Pomerantz’s agreement occurs as the second part of the adjacency pair of conversation mentioned above, while Hornero et al.’s agreement shows up in a three-turn organization.. 14.

(36) In this study, Pomerantz’s definition of agreement is adopted for several reasons. First, Pomerantz’s definition is coordinated with the dual-turn organization mentioned by many scholars in the section of “Preference Organization,” while Hornero et al.’s three-turn organization cannot fit in the concept of adjacency pairs. Second, after the examination of the data, the follow-ups do not always occur so that the third turn is not obligatory but optional. For example, it is optional for the speaker who gives the evaluation acknowledges that he/she hears agreement from the other speaker. Therefore, Pomerantz’s definition of agreement which is in the structure of the adjacency pair is adopted, while Hornero et al.’s version is not.. 立. 政 治 大. 2.5.2. Speech Act Analysis of Agreement. ‧ 國. 學. As what have been reviewed above, Austin (1962) proposes three essential components in speech act: locutionary act, illocutionary act, and perlocutionary act.. ‧. As for illocutionary act, Searle (1975) classify it into five kinds: representatives,. y. Nat. sit. directives, commissives, expressives, and declarations. Agreement, accordingly,. n. al. er. io. belongs to the category of “expressives” because the utterances of this kind “have the. i Un. v. function of making known the speaker’s psychological attitude towards a state of. Ch. engchi. affairs which the illocution presupposes” (Leech, 1983: 106). In agreeing with others, the speaker reveals his/her compatible attitudinal judgment to the hearer to support them. Nevertheless, not all of agreements are proffered directly. Agreements can be an indirect speech act. As for indirect speech act, two illocutionary act compose it: Primary illocutionary act, and Secondary illocutionary act. For example, the speaker can propose an account on the surface content to elaborate the previous speaker’s evaluation. This account is as Secondary illocutionary act. The speaker’s true purpose. 15.

(37) of proffering the account is to agree with the previous speaker. In other words, agreement is Primary illocutionary act.. 2.5.3. Pragmatic Strategies of Agreement Among the studies related to agreement, few researchers list the linguistic strategies of agreement. Most of the studies only collect the “message components” of agreement or the “formats” of agreement (Baym, 1996; Mori, 1999). Nevertheless, some components which are listed as linguistic forms of agreement should be classified as pragmatic strategies because they demonstrate the ways of speaking. For. 政 治 大. instance, Mori (1999) finds that the Japanese speakers would reinforce their claim of. 立. agreement by using the strategy “elaboration”. Further developing the talk can. ‧ 國. 學. demonstrate people’s alignment with the prior speaker beyond a mere claim of agreement. These elaborations are often found initiated by the causal markers, such as. ‧. “datte, dakara, and -kara.”. y. Nat. io. sit. Very few studies investigate the pragmatic strategies of agreement. Therefore,. n. al. er. previous studies on pragmatic strategies of disagreement are reviewed first because. Ch. i Un. v. although agreement and disagreement are contrary speech acts, the procedure of. engchi. proffering either of two is similar. Liu (2009), in her investigation of how the social factor, age influences the interaction between the forms and the strategies of disagreement, finds that nine pragmatic strategies are applied in showing disagreement. These strategies of disagreement include correction, account, challenge, defense, partial disagreement, clarification, suggestion and confirmation. Yang (2010) observes how the EFL learners in Taiwan are affected by their gender and performs differently in the forms and the strategies when disagreeing with each other. She proposes seven strategy types by the combinations of with or without “head act” and “Supportive Move(s)” (Blum-Kulka et al., 1989). The supportive moves can further 16.

(38) be divided into mitigated disagreement and aggravated disagreement. The sub-strategies of mitigated disagreement include account, apology, gratitude, justification,. partial. agreement,. persuasion,. self-defense,. and. suggestion.. Subcategories of aggravated disagreement contain accusation, confrontation, contradiction, request, rhetorical question, and moralizing. In the current study, pragmatic strategies mentioned above are adopted and adapted for data analysis.. 2.5.4. Social Constraints: Power and Solidarity Power and solidarity are also related to how people agree with each other when. 政 治 大. the social factor—gender is involved. In this section, the notion of power and. 立. solidarity, the general ideas of linguistic gender differences, and related works of. ‧ 國. 學. gender differences in agreement are reviewed.. ‧. 2.5.4.1. The Notion of Power and Solidarity. Nat. sit. y. The concept of power and solidarity is initiated by Brown and Gilman (1968).. n. al. er. io. They propose that linguistic strategies are governed by two forces, power and. i Un. v. solidarity. Power can be related to the differences of physical strength, wealth, age,. Ch. engchi. gender, institutionalized role in the church, the state, the army or within the family. Tannen (1986) also defines power as “controlling others –an extension of involvement, and resisting being controlled – an extension of independence.” In his paper The Concept of Power, Dahl (1957) gives a similar definition that power is when person A has ability to get person B to do something that is against person B’s will. According to all the works above, power means people are in a hierarchical relationship with one dominating over the other. As for solidarity, Tannen (1986) defines it as “the drive to be friendly, similar to what we have called rapport.” Later, Tannen (1994) further proposes that solidarity is. 17.

(39) associated with symmetrical relationship and emphasizes on social equality and similarity. However, she also mentions that the concept of power and solidarity can be ambiguous and paradoxical. For instance, a linguistic form may serve the function of showing power, solidarity, or both, and it depends on the varieties of participants, topics, and settings. Among all the social factors power appearing along with, gender is chosen to be analyzed in this study. Hence, it is necessary to consult related studies on gender differences.. 政 治 大. 2.5.4.2. Gender Differences in Power and Solidarity. 立. In different cultures, people have different language “performance expectations”. ‧ 國. 學. for each gender (James and Drakich, 1993: 286-301). How men and women speak is constrained by their cultural or social norms. Therefore, gender differences are. ‧. recursively reinforced. For example, men are allowed to curse and cuss to show. y. Nat. io. sit. masculinity, while women who speak dirty words would be taken as the departed or. n. al. er. even a person with lower social class. Consequently, men curse a lot in daily. Ch. conversation, while women do not.. engchi. i Un. v. Many researchers find other general differences between men and women. For example, Woods (1997) noted that men emphasize more on competition and the ways of earning power and status; by contrast, female tends to be more cooperative, provides more support and solidarity. Besides, men are speaker-oriented, while women are listener-oriented. Similarly, Tannen (1990: 24) believes that for men, conversation is a way to negotiate for the upper status, and protect themselves from being put down. In contrast to men, women think that negotiation is for closeness and in which people try to exchange support and confirmation, and to reach consensus. It means that men value power more, while women value solidarity more. Tannen even 18.

(40) thinks that men and women are like speaking two different languages and having cross-cultural communications. To examine Tannen’s theory of “double-track communication system” is one of the foci in this study. For studies on gender difference of agreement, there are some evidences to support that women tend to seek agreement to a greater extent than men do, both in same-sex and mixed-sex contexts (Kalcik, 1975; Leet-Pellegrini, 1980; Edelsky, 1981; Coates, 1989; Holmes, 1995: 60). For instance, Coates (1989: 118) concludes that women like to build on each other’s contribution, complete other’s sentences and affirm other’s opinions in a very cooperative state. Eckert (1990: 122) even comments. 治 政 that “not one topic is allowed to conclude without an 大 expression of consensus” in her 立 investigation on a group of adolescent girl. In their research on agreement markers, ‧ 國. 學. Guiller and Durndell (2006) also find that female are more likely to express. ‧. agreement than men.. sit. y. Nat. From the studies presented above, people can notice some inadequacies. First, it. io. er. is not specifically pointed out that how men and women differentiate from each other. al. in the usage of the agreement forms and pragmatic strategies. Second, there is a lack. n. iv n C of Mandarin Chinese research on h gender differencesUin agreement. Chinese people engchi have lived in the patriarchal society for a long time. A similar result that women agree more and men agree less is expected because of their asymmetrical relationship as well as their different value toward power and solidarity. Nevertheless, it is still worthwhile to do this research on how Chinese proffer agreement because Chinese culture is distinct from Western culture. Through the analysis of this paper, people can know how different genders manipulate linguistic contents and strategies to agree with others in Mandarin Chinese.. 19.

(41) 2.5.5. Linguistic Features of Agreement Pomerantz (1984) observes that agreement has some general features. For example, the agreement turn is occupied by agreement components in contrast with disagreement which is often prefaced. Agreement is often with agreement markers and with a minimization of gap between the prior assessment and the agreement turn. However, Kotthoff (1993) suggests and verifies that the performance of agreement or disagreement depends not only on the propositional content of the prior turn but also on contextual factors, such as genre, social factors, institutional situation, and culture. Pomerantz (1984) divides agreement into three types: the upgrading agreement,. 治 政 the agreement with same evaluation, and the downgrading agreement. This 大 立 classification has been adopted and adapted by most of the studies (Kuo; 1994; ‧ 國. 學. Mulkay, 1985; Baym, 1996; Rattai, 2003). Upgrading agreements often occur as parts. ‧. of a cluster of agreements or agreement series. Two linguistic features, a stronger. sit. y. Nat. evaluative term and an intensifier, are found to mark upgrading agreements.. io. er. As for the agreement with same evaluation, the most common strategy used is. al. repetition. Brown and Levinson (1987) indicate that agreement could be stressed by. n. iv n C repeating part or all of the evaluation context. Repetition can stress the h ein nthegprevious chi U speaker’s interest, surprise, or emotion.. As for downgrading agreements, using weaker evaluation term is their linguistic features. Pomerantz (1984) gives some “weaker” synonyms. For instance, substitute “beautiful” with “pretty.” Kuo (1994) investigates the procedures of showing agreement and disagreement in a 10-minute call-in radio program. In her data, Kuo finds three forms of agreement: repetition, upgrading agreement, and back-channel responses. As for upgrading agreement, two techniques, “stronger evaluative terms” and “intensifying modifiers” are used. As for back-channel responses, Kuo supports Pomerantz’s (1975) claim that 20.

(42) these positive acknowledgement tokens (e.g., mhm, yeah and right) are weak agreement forms. It means that these tokens not only function as the reassurance of listenership but also show agreement. But in this study, the back-channel responses are not counted as agreement markers because it is difficult to prove these tokens function to agree with others or just to show listenership. Baym (1996) takes Pomerantz’s (1987) categorization as the base to investigate agreement and disagreement in the genre of computer-mediated communication. She finds three means to create agreement: explicit indicants of agreement, making an evaluation, and reasoning through elaboration. Explicit indicants of agreement contain. 治 政 two sub-types. They are explicit phrase “I agree” and strong 大 agreement tokens such as 立 “indeed” and “you said it.” Making assessment, which is adopted from Pomerantz ‧ 國. 學. includes upgrades, downgrades, as well as matching agreements. Reasoning through. ‧. elaboration as the third way to show agreement is a new category not included in. y. sit. io. er. viewpoint.. Nat. Pomerantz’s studies. By giving a reason, people are assumed to have the same. al. In analyzing Japanese conversations, Mori (1999) finds four features of. n. iv n C agreementhtokens, repetition, e n g c h i U early. agreement: the use of. delivery of agreement. (overlapping), and semantic or phonological intensification. Rattai (2003) consults Pomerantz’s categorizations and investigates agreement as well as disagreement features in Russian News interviews. In Rattai’s classification, agreement is divided into strong agreement and weak agreement. According to Rattai, strong agreement has three subcategories—direct agreement, upgrading, and same evaluation, while weak agreement has agreement via interviewer, affiliation, token agreement, and downgrade. Rattai’s biggest contribution is that she expands the meaning of upgrading agreement and includes some implicit agreements that Pomerantz does not classify. Rattai indicates that by doing upgrading, the speaker not only agrees with his/her 21.

(43) interlocutors but also add new but relevant information to the prior evaluation. Nevertheless, Rattai does not further specify what the new information means; thererfore, it is not clear whether the new information means a reason of agreement, a new angle of the topic, or something else. Gao et al. (2006) investigate the structure of agreement in Mandarin Chinese, and discover six linguistic features: agreement token, repetition, explanation/addition, concluding for the prior turn, silence, and repair. Among all, data of silence and repair are few. Based on the previous studies, agreement is concluded to have some general. 治 政 patterns. When agreement is as a preferred response, it大 is often stated strongly, shortly, 立 and directly. And from the perspective of degrees, agreement can be upgrading, ‧ 國. 學. preserving or downgrading by certain linguistic markers.. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 22. i Un. v.

(44) Chapter 3 Methodology. This section is divided into four parts: data collection, procedures of data analysis, classification of agreement, and pragmatic strategies in agreement. First, data collection is to indicate where the data come from and the restriction of the data. Second, procedures of data analysis are provided. Then, the structure of agreement will be first classified into a head act and supportive move(s) (Blum-Kulka et al.,. 政 治 大 upgrading, preserving, and downgrading agreements. Finally, pragmatic functions in 立 1989). And according to degree of agreeing, agreements can also be classified into. ‧ 國. 學. agreement with some examples will be presented.. ‧. 3.1. Data Collection. sit. y. Nat. In this section, data resource and the delimitation of data are introduced first.. io. n. al. er. Then, social distribution of subjects is provided.. 3.1.1. Data Resource. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. The data of agreement analyzed in this thesis was collected from The NCCU Corpus of Spoken Mandarin (2011). Eight face-to-face conversations lasting from 15 to 20 minutes long were used as the data base of this thesis. Among them, two conversations are Male to Male, two are Female to Female, and four are Male to Female. Participants in these conversations are either friends or couples. The topics of these conversations are all about daily life. For the restrictions of data, first, only the agreement based on personal judgments was included, while the agreement based on a fact or content was excluded. For example, data were included when the previous speaker says, “The flower is 23.

數據

+7

相關文件

二、 學 與教: 第二語言學習理論、學習難點及學與教策略 三、 教材:. 運用第二語言學習架構的教學單元系列

大學教育資助委員會資助大學及絕大部分專上院 校接納應用學習中文(非華語學生適用)的「達 標」

• 「在香港定居的非華語學生與其他本地學 生,同樣是香港社會的下一代。……為促

學習語文必須積累。語文能力是在對語文材料大量反復感受、領悟、積累、運用的過程中

name common laboratory apparatus (e.g., beaker, test tube, test-tube rack, glass rod, dropper, spatula, measuring cylinder, Bunsen burner, tripod, wire gauze and heat-proof

新高中課程中國語文科第十個選修單元:「普通 話與表演藝術」中提到的學習目標,正是期望學 生能「欣賞不同類型的普通話表演藝術,學習語

潘銘基, 1999 年畢業於香港中文大學中國語言 及文學系,繼而於原校進修,先後獲得哲學碩士

如何 如何在小學語文課程中加強中華文化的學習 在小學語文課程中加強中華文化的學習 在小學語文課程中加強中華文化的學習