行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權及服務重要性對消費者公

平知覺及滿意度之影響

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC94-2416-H-009-003- 執行期間: 94 年 01 月 01 日至 94 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立交通大學管理科學學系(所) 計畫主持人: 張家齊 報告類型: 精簡報告 報告附件: 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 94 年 11 月 1 日

消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權及服務重要性

對消費者公平知覺及滿意度之影響

中文摘要 服務缺失的補救對於服務業的成功與否實有舉足輕重的影響,過去文獻指 出,服務缺失的補救對於廠商到底是能留住客戶還是將顧客拱手讓人有絕大的影 響。雖然國內學術界已開始對於不同服務補救措施之效用開始有所研究,但許多 的相關研究還停留在萌芽的階段。 本研究探討一心理變項(i.e.,提供消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權)是否能 提升現有服務補救措施之效用,本研究操弄心理變項--提供消費者對服務補救措 施之選擇權--並研究此變項對於消費者對於服務補救的評價。 近年來,消費者之公平知覺開始受到學者的注意,所以,除了研究提供消費 者對服務補救措施之選擇權對於顧客評價之影響,本研究還探討提供消費者對服 務補救措施之選擇權對於不同構面之消費者公平知覺所產生的影響。具體說來, 消費者之公平認知扮演中介變項的角色,提供消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權經 由提高消費者之公平知覺而進一步提高顧客對於服務補救措施之滿意度。本研究 亦探討服務重要性是否調節提供消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權與不同構面之 消費者公平認知之間的關係。研究結果驗證了的大部分的假說。 另外,本研究除了考慮公平知覺對於顧客對於服務補救措施之滿意度的影響 之外,亦同時檢驗顧客對服務疏失歸因(e.g.,對於疏失穩定性及疏失是否是為廠 家所能控制)對於顧客對於服務補救措施之滿意度的影響,研究結果指出,當控 制公平認知之影響時,顧客對服務疏失的歸因並未對顧客對於服務補救措施之滿 意度造成顯著的影響。 關鍵字: 選擇,服務補救,公平知覺,服務疏失歸因, 服務重要性TheEffectofChoiceProvision,Customers’FairnessPerceptions,and Attribution on Customer Satisfaction in a Service Failure

ABSTRACT

Service failures and recoveries have been identified as critical determinants of serviceprovider’srelationship with customers.Priorserviceliteraturesuggeststhat customers are likely to switch service provider, if they can not successfully recover from service failures. Hence, exploration into additions to the current practices prevailing in the industry is warranted.

This study utilized a psychological theoretical framework to predict the

effectiveness of providing customer alternative solutions as a recovery program. The magnitudes of choice provision on various justice constructs were assessed. One of the goals in this study was to investigate the differential effects of providing

customers with alternative solutions to a service failure on an array of justice

dimensions, which, in turn, would affect customer satisfaction with service recovery. This study also examined whether the effect of proving customer a choice of recoveries on customers’fairnessperceptionsoftheservicewascontingentupon the importanceoftheservice.Lastly,how customers’attributionsaffecttheirsatisfaction judgment about the service recovery is also investigated in this study.

The results revealed that the effect of choice was contingent upon the importance oftheservice.Although customers’perception ofdistributivejusticewasinfluenced by neither of the proposed predictors (i.e. choice and service importance), their

perceptions of procedural justice and interactional justice were significantly affected by the interaction between service importance and choice provision. However, the interaction direction was not as hypothesized. While it was hypothesized that the effect of choice would have a more significant effect on justice perceptions when the service was of greater importance, the results suggested the opposite. When a service was of greater importance, providing alternative solutions due to a failure in

delivering that particular service had a smaller impact on customer satisfaction than when the service was of less importance. Therefore, it could be concluded that the effect of choice was reduced as the service importance increased.

Thisstudy also demonstrated when customers’perceptionsofdifferent

dimensions of fairness and the different dimensions of their attribution to the failure were considered simultaneously, the effect of customer attribution was not significant anymore. The discussion of the occurrence of phenomena described above is included in this paper.

Keyword: choice, service importance, service failure and recovery, attribution, fairness perception

Introduction

Even thebestserviceprovidercannotguarantee an absolute“failure-free” service environment (Hart et al. 1990), due to the unique nature of a service (i.e., coproduction and inseparability of production and consumption). Therefore, it may be useful to understand how a firm can effectively recover from its own service failure, and how it can alleviate the negative impact of failures when consumers cannot be completely recovered from the failures.

Service recovery has been identified as a critical factor that determines customers’evaluationsand reactionsto theservicefailurescaused by theservice providers. Failed attempts to recover from service failures could lead to customer dissatisfaction (Tax et al. 1998) and switching behavior (Keaveney 1995). Fortunately, customers might not always be furious after a service failure. In a service failure incident, firms can actually have the opportunity to win their customers back instead of further harming their relationship with customers (Smith and Bolton 1998). The key is successful service recovery. As Tax and Brown (1998, p.86) put it, “Some customers are actually more satisfied with a firm that follows a service failure with a remarkable recovery than they would have been had the failure not occurred in the firstplace”.

Successin recovering from one’sservicefailure for a service provider can affect the financial performance of organizations. Reichheld and Sasser (1990) reported that firms can increase their profit by 100% by simply increasing their

customerretention rateby 5%.Extending thecustomerrelationship’slifespan beyond a certain period of time enhances the value of a customer exponentially. Usually, after staying for five years with the same company, the value of that customer doubles. Investments for enhancing service recovery efforts of a firm are likely to bring high returns to companies. For example, by ensuring their customers that problems will be dealt with effectively, the Hampton Inn hotel chain realized an $11 million increase in sales revenue (Ettorre 1994).

While the importance of service recovery has been acknowledged, few studies have been dedicated to explore possibilities to increase the effectiveness of service recovery except a study by Chang (2004). Chang (2004) demonstrated that by providing customersalternativesolutionswould increasecustomers’senseofcontrol, which eventually leads to higher customer satisfaction with service recovery and overall service encounter.

Prior studies have shown that fairness perceptions are also associated with customers’satisfaction with theservicerecovery and overallsatisfaction (Smith et al. 1999). In this research, I propose to investigate the relationship between providing customers alternatives and itsimpacton customers’perception offairnessand the

mediating role of customer fairness perceptions on the relationship between consumer choice and their satisfaction with service recovery and total satisfaction.

CONCEPTS AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Service Failure

Gronroos (1988, p.13) implicitly defined service failures as a problem of servicequality.Itoccurswhen “something goeswrong orsomething unpredictable unexpectedly happens.”They can bedescribed “activitiesthatoccurasa resultofa customer’s perceptions of initial service delivery behaviors falling below the customer’sexpectationsor“zoneoftolerance”(Zeithaml,Berry,and Parasuraman 1993).

Using a sample from the hotel, restaurant and airline industries, Bitner et al. (1990) suggested that service failures can be subsumed under the following three major categories 1) employee response to service delivery system/product failures, 2) employee response to customer needs and requests, and 3) unprompted and unsolicited employee actions. The first group mainly describes the service failure itself, such as slow or unavailable service. An example is a delayed flight. The second category emphasizes special treatments a service provider offers to address a customer’sneeds.Failing to accommodateavegetarian flierforhis/hermealisan example.Thelastcategory isrelated to an employee’sbehaviorwhen delivering the service. A front desk clerk paying more attention to the television while customers try to check in is an example. Subsequent work has demonstrated support for this typology (Hoffman et al. 1995).

Servicefailureshasbeen associated positively with customers’switching behavior (Keaveney 1995) and negatively with customer satisfaction and repurchase intentions (Smith et al. 1999) and word-of-mouth (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002). On average, businesses never hear from 96 percent of their unhappy customers (Lipton 2000). Dissatisfied customers generally turn their backs on the service provider and tell an average of nine people about their negative experiences (Blodgett et al. 1993). What’smore,thenegativeimpactofservicefailureisfarmoreinfluentialthan its counterparts (e.g., successful service encounters) (Anderson and Sullivan 1993). For example, it takes up to as many as 12 positive experiences with a service provider to offset the negative impact of one bad experience (Smith and Bolton 1998).

Service Recovery

Zemke and Bell (1990) defineservicerecovery morespecifically:“…[a] thought-out, planned process for returning aggrieved customers to a state of

satisfaction with the organization after a service or product has failed to live up to expectations.”

Hoffman, Kelley, and Rotalsky (1995) studied restaurant recovery strategies and found that they can be collapsed into 8 major categories: free food, discounts, coupons, managerial intervention, replacement, correction, apology, and no action.

Poorrecovery effortscan end thefirm’srelationship with customers (Schneider and Bowen 1999) while excellent recoveries can further strengthen customer loyalty and increase repurchase intention (Smith and Bolton 1998). Some researchers even suggest that the execution of effective recoveries might have a greater impact on customer satisfaction than the attempt to provide customers a “servicefailurefree”shopping environment(Kelley et al. 1993).

The positive impact of successful recovery efforts include increased market share (Fornell and Wernerfelt 1987), higher return on investment (Tax and Brown 1998), and better financial performance of the firms (Tax et al. 1998).

Consumer Choice

Choice is the freedom of selecting an alternative from a choice set instead of being assigned a given alternative from the same choice set by an external agent (i.e., other individual or chance) (Botti 2002). The mere perception ofone’shaving a choicecan haveapositiveimpacton an individual’ssatisfaction with theoutcome (Botti 2004). This psychological satisfaction is beyond the explanation using traditional rational economic theory (Benartzi and Thaler 2002). In a service failure context, it refers to the freedom to select from alternative recovery offers after a service failure.

Consumer Choice and Perceived Justice

Having the opportunity to choose among alternative recovery offers is likely to affectcustomers’perceptions of the different types of justice. In the following sections,theeffectofprovision ofchoiceon customers’fairnessperceptionswillbe discussed.

EffectofCustomerChoiceon Customers’PerceptionsofDistributiveJustice

Distributive justice refers to the outcome fairness of the service recovery. The evaluation of the outcome is determined by the rewards and resources available to the customer in a recovery (Goodwin and Ross 1992). Tax et al. (1998, p.67).

operationalize distributive justice as“whethertheoutcomewasperceived to be deserved.”Thisoperationaldefinition implicitly containsAdam’s(1963,1965) input/output concept in equity theory. That is, consumers compare their losses due to

service failures and the gains they obtain from aservicefirm’srecovery offersto determine whether the exchange is fair (Smith et al. 1999). In a service failure context, it can be in the form of discount, refund, credit, upgraded service, free service, or correction of charges (Kelly, Hoffman and David 1993).

According to rational economic theory, having the opportunity to choose allows individuals to choose an option that can provide the most utility to them

(Benartzi and Thaler 2002). Even when no extra benefits can be obtained, the freedom to choose from different alternatives can enhance the attractiveness of the chosen item. Psychological theories grounded in cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger 1957) suggest that there will be a range in the attractiveness among options. That is, the chosen objects tend to become more attractive after the decisions are made (Tversky and Slovic 1988). This is because when people choose a certain outcome, they feel responsible for the chosen outcome. According to cognitive dissonance theory

(Festinger 1957), it is hard to justify why they would choose an unattractive outcome. Therefore, people who choose a certain outcome will tend to perceive the outcome to be more attractive in order not to attribute an unwise decision to their poor

decision-making ability. The responsibility makes people unconsciously enhance the attractiveness of the choice, since people do not want to admit that they make poor choices.

Consumer researchers have ascertained that people tend to judge their choices morepositively oncethey arechosen,aphenomenon called “post-choicebolstering” (Brown and Feinberg 2002; Chernev 2001). Botti (2002) also pointed out that “people who have committed themselves to a choice engage in forms of preference

distortion.”Clearly,theperception ofoneselfasachooseralonecan lead to ahigher evaluation oftheoutcomeofthechoicethan theevaluation ofa“non-chooser”who receives the same benefit (Botti and Iyengar 2003). Hence, Blodgett, Hill, and Tax (1997) suggest that retailers should ask complainants what they desire in terms of compensation for service failure. This suggests the positive effect of allowing customer choice on the likely increased perceived value of the particular choice.

EffectofCustomerChoiceon Customers’PerceptionsofProceduralJustice

Procedural justice refers to the fairness of the means through which ends are accomplished (Lind and Tyler 1988; Tax et al. 1998). In consumer research, however, the operational definition of procedural justice varies across studies, though

essentially they represent the same construct. Some studies only measure/manipulate oneofitsdimensions.Forexample,in Goodwin and Ross’sstudy (1992),procedural justice represents only the opportunity to expressone’sviewpoint(thevoiceeffect). Smith et al. (1999) manipulated only the responsiveness and timeliness dimension to

investigate the effects of these two dimensions; they acknowledge, though, that procedural justice may still involve other elements, such as decisional control, process control, and accessibility. A more thorough definition of procedural justice appears in the work by Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran (1998). They summarized previous justice literature and identified five major elements in consumer complaint-handling procedures: accessibility, control over the process, flexibility, convenience, and timeliness.

Although procedural justice has various operational definitions, in a service failurecontext,itstillrepresentscustomers’perception ofthefairnessofthe procedure involved in recovering from the failure. Providing customers a choice is likely to enhance their perceptions of procedures since provision of a choice permits customers to have an input on the final outcome in the recovery and to feel that they can affect the outcome they are receiving. As a result, they are likely to feel more in control over the process of creating the recovery. Consequently, they are more likely to perceive higher degree of procedural justice in the recovery, since process control has been identified as one of the important elements in procedural justice (Smith et al. 1999; Tax et al. 1998). The empirical research by Goodwin and Ross in service failures(1992)supportsthisview.They claim thattheopportunity to expressone’s opinion represents participation, especially in terms of presenting information to responsivedecision makers,which can strengthen customers’beliefthattheir participation mightinfluencetheoutcomeand henceenhancepeople’sperception of procedural justice. Mills and Krantz (1979) also pointed out that choice can enhance customers’feeling ofactiveparticipation in theprocedure.Therefore,providing the opportunity of participation and the belief that customers can affect the outcome should bepositively associated with customers’perception ofproceduraljusticein service recovery since both process control and decisional control are essential elements in the constructs of procedural justice (Lind and Tyler 1988; Smith et al. 1999; Thibaut and Walker 1975).

Effect of Customer Choice on Customers’PerceptionsofInteractionalJustice

Interactional justice (Bies and Moag 1986) refers to the manner through which information is exchanged and outcomes are communicated. In a service failure

context, interactional justice is interpersonal treatment that customers receive during service recovery (Smith et al. 1999; Tax et al. 1998).

Choice can enhance people’sperception ofinteractionaljustice,since

providing customers with different alternative solutions to their problems conveys the message about earnestness to compensate customers. When customers are provided with alternative recovery offers, they are likely to perceive that the firm expends

effort to create these options in order to compensate them (Tax et al. 1998). Since effort is an essential dimension in interactional justice in a service failure context, providing customersachoicein recovery offersshould increasecustomers’ perceptions of interactional justice.

Furthermore,providing customersachoicecan convey serviceproviders’ sincerity to solve the problem, since they have taken some action to compensate their customers.Italso communicatesthefirm’sresolution to resolvetheproblem and willingness to customize the solution for their customers, even if that might take more time or expend more company resources.Allthisshould enhancecustomers’

perception of service provider efforts.

Providing customers a choice means that the firm knows customers might have different needs and are willing to address them with different alternative recovery offers. It conveys the message that the firm acknowledges individual preferences among customers and is willing to customize different solutions for their customers. At some level, this is part of relationship marketing, as customization is a significant element of relationship marketing (Berry 1995). The willingness to

provide individualattention mightfitinto theempathy category ofTax etal.’s(1998), and therefore, should be positively related to perception of interactional justice.

Based on the above statements, the following hypotheses are posited:

H1: When consumers encounter a service failure, those who are provided with

alternative recovery options will perceive a) the outcome, b) the procedure, and c) the interaction with the service provider to be fairer in term of service recovery than will those who are not provided alternative recovery options.

Moderating Role of Service Importance on the Relationship between Choice and Justice

In a study validating the scale of measuring customer’s willingness to relinquish control,O’connerand and Siomkos(1994) reported that importance of the purchasing task is one of the crucialfactorsthatinfluencecustomer’swillingnessto relinquish control. As procedural justice researchers point out, control is an essential element of procedural justice (Thibaut and Walker 1975; Tyler et al. 1996). Therefore, allowing customers to have inputs (e.g., to be able to decide what recovery alternative they can receive) is likely to lead to higher evaluations of procedural justice. For tasks of more importance, the less likely customers will relinquish their control over those tasks. Therefore, providing them the opportunity to express their input can have a

positiveimpacton customers’fairnessperceptions,particularly on thedimension of procedural justice.

Along the same line, the relationship between customers’ perceptions of distributive justice and choice provision should be augmented when service importance was higher. According to cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger 1957), the more important a decision is, the more likely a person would have to enhance their favorable attitude toward the selected option. Otherwise, the tension created by inconsistentthoughtsin theconsumer’shead (e.g.,Imadeawrong choicebecauseI am stupid vs. I am a wise consumer) would be elevated to a greater degree when the decision was more important to the customers. To put it in another way, when a purchase task is more important to the customer, the more important it is to them to comeup with the“rightdecision”.Hence,herewillbeagreaterneed for customers to persuade themselves that they have made the right choice. Therefore, when service importance increases, choice provision should have a larger effect on customers’ perceptions of distributive justice.

The relationship between choice provision and customers’ perceptions of interactional justice will conceivably augment when service is more important to the customers. The rationale behind this is when the service importance is high, customers are more likely to have a greater need to see service providers expending more efforts in order to satisfy them. Therefore, when alternative solutions are provided in high service importance condition, the effect on interactional justice perception will conceivably be stronger than in low service importance condition.

H2: The more important the service is to the customer, the stronger the impact

choicehason customers’perception ofa)distributivejustice,b)procedural justice and c) interactional justice.

Perceived Justice and Customer Satisfaction

In the following section, the details of how each justice concept can affect customers’satisfaction with theservicerecovery willbediscussed.Particularly, how each construct influences customer satisfaction in different fields (including both service and non-service context) will be illuminated.

Effect of Distributive Justice on Customer Satisfaction

Numerous studies have provided the linkage between distributive fairness perception and customer satisfaction. Although there are as many as 17 rules of distributive justice (Ries 1986), the most prevalent one is equity followed by equality and need (Tax et al. 1998). Consumer researchers use a combination of

social exchange theory and equity theory to explain the positive effect distributive justice has on customer satisfaction (Smith, Bolton and Wagner 1999). Smith et al. (1999) point out that while all three dimensions of perceived justice account for more than 60% of the variance in satisfaction, a fairly large percentage of the explained variance is accounted for by distributive justice.

Other research has also demonstrated a direct, positive effect of distributive justice on customer satisfaction in both experiments and a field study (Goodwin and Ross 1992; Maxham III and Netemeyer 2002; Tax et al. 1998). Using different scenarios ranging from dental service, airline, auto repair and restaurant, Goodwin and Ross (1992) tested a sample of 285 undergraduate students attending urban universities in the Midwest and Southeast. They concluded that outcome fairness plays an important role in shaping customer satisfaction in all the industries except dental service. Analyzing data from employees (who answered questionnaires as everyday consumers) from four different industries (telecommunication, health care insurer, bank and ambulatory and emergence service provider), Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran (1998) reported an overall direct impact of size 0.39 of

distributive justice on customer satisfaction. A field study (banking service) showed that distributive justice has an impact on both satisfaction with the service recovery and the overall satisfaction with the firm. However, its impact on overall satisfaction with the firm was smaller than procedural and interactional justice (Maxham III and Netemeyer 2002).

It should be noted that distributive justice might interact with other dimensions of justice (procedural and interactional justice) on customer satisfaction. For

example, it is suggested that distributive justice interacts with procedural justice and/or interactional justice to determine customer satisfaction (Goodwin and Ross 1992).Blodgett,Hilland Tax (1997)furtherproposed a“two-stagetheory”forthe effect distributive justice has on customer satisfaction-related constructs,

word-of-mouth, and repatronage intention. They conclude that the effects of distributive justice on these two constructs are contingent upon the level of

interacational justice. To be more specific, distributive justice only has its effect on customers’evaluation when theinteractionaljusticeexceedsacertain cutoff point. Hence, if customers are treated by rude personnel during the service failure and/or recovery, the level of recovery does not matter. It is only when customers are treated with proper behavior that distributive justice has a positive impact on customers’negativeword-of-mouth and repatronage intention. But, overall, distributive justice still appears to be positively associated with customer satisfaction.

Effect of Procedural Justice on Customer Satisfaction

Organizational psychologists have identified procedural justice, the fairness of rules and procedures by which allocation decisions are made, as an important factor in enhancing job satisfaction (Manogran et al. 1994; Moorman 1991). That is, when the rules and procedures about resource allocation are consistent, unbiased,

accurate, correctible, and allowed employees to have input into the decisions, higher job satisfaction will result.

In a recent study, Maxham and Netemeyer (2002) define procedural justice as the fairness of policies and procedures involving the recovery efforts. Using a sample composed of consumers who filed complaints to their banks for the first time, they ascertained that procedural justice is positively associated with overall satisfaction with the firm though its correlation with satisfaction with service recovery did not reach a significant level. Smith et al. (1999) found that procedural justice (only the responsiveness and timeliness elements) is positively associated with customer satisfaction. Goodwin and Ross (1992) also reported a positive association between procedural justice (specifically the voice part) and customer satisfaction. They suggest that providing customers the opportunity to communicate with service providers and present information that might have an influence on servicefirm’sdecision aboutrecovery can havea salutary effecton customer satisfaction.

It should be noted that, in their study, the effect of procedural justice on customer satisfaction was greatest when the outcomes are positive (high

distributive justice). That is, providing customers the opportunity to provide input does not have as much positive impact on customer satisfaction when outcomes for the customers are negative. Thisisconsistentwith thenotion of“frustration effect” in previous work in social psychology (Folger 1977; Folger et al. 1979). The

feeling of“sham”participation islikely to increasecustomer’s frustration.

Effect of Interactional Justice on Customer Satisfaction

Smith etal.(1999 p.357)defined itas“themannerin which information is exchanged and outcomesarecommunicated”.In organizationalbehaviorliterature, fairness treatment from supervisors has been associated with job satisfaction

(Cropanzano and Greenberg 1997; Masterson et al. 2000; Tyler et al. 1996). When employees are treated fairly by their superiors, they are more willing to accept the decisions made by the organization and tend to be more satisfied with the decisions. The major theory organizational behavior researchers use is social identity theory. It posits that people interact with others because they need to gather social identity relevant information. Based on the information they gather, they then make

inference about their social status. The same theory can be applied to consumers as well. Just as employees, customers learn their social identity status through the interaction with service agents. In a service encounter, whether they are treated with respect informs them about their social status. When they are not treated with the proper manner (e.g., respect), they receive unfavorably information about their identify status, which abates customer satisfaction. When a service failure occurs, customers can also refer their social status from treatments they receive throughout the service recovery process. If customers are not treated with proper manners, their social identity is likely to be threatened. If it is the case, then no compensation can effectively help service providers to recover from the failure (Blodgett et al. 1997). Empirical research also supports this view. In the summary works about service failure and recovery, it is not uncommon to find customers receiving favorable recovery outcomes allocated by fair procedures feeling furious simply because the service agents do not treat customers with respect and dignity (Hoffman et al. 1995; Kelley et al. 1993). That alone can make such a huge influence that it makes people swear to never patronize a store ever again (Bitner et al. 1990).

Blodgett,Hilland Tax (1997)suggestthatin aretailsetting,customers’ satisfaction, though also dependent on the outcome, is largely determined by interactional justice. If the service providers react to a service failure in an inappropriate manner, customers will not be satisfied regardless of the

favorableness of the outcome. Additionally, customers receiving partial redress in a courteous manner are more likely to repurchase than those who receive a full refund but are not treated with respect and dignity. Smith et al. (1999) reported a positiveeffectofinteractionaljusticeon customers’satisfaction with service encounters. They found that apology and organization-initiated recovery efforts, factors that influence interactional justice, can enhance customer satisfaction with service encounter. When customers receive apology and/or organization-initiated recovery efforts, they are more likely to perceived greater interactional justice and hence be more satisfied with the service encounter. The same positive impact of interactional justice on customer satisfaction has also been reported in the study conducted by Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran (1998). Furthermore, interactional justice has the largest effect on customer satisfaction among all three dimensions of justice. In the study by Goodwin and Ross (1992) where interactional justice was conceptualized as an apology, interactional justice also has a positive impact on customer satisfaction when outcomes are favorable. In the complaining handling literature, interactional justice (mainly explanation) is also found to lead to greater complainant satisfaction (Conlon and Murray 1996).

positively associated with interactional justice. That is, how well the customers are treated by the service provider during the service recovery will have an impact on customer satisfaction. Based on earlier arguments, the following hypothesis is promulgated.

H3: When consumers encounter a service failure, those perceive a) the outcome

b) the procedure c) the service provider being fairer in terms of service recovery will be more satisfied with the service recovery.

Attribution of the Service Failure and its Effect on Customer Satisfaction with Service Recovery

Attributions,theassignmentofcausalinferences,can influencepeople’s evaluation and subsequent behavior (Weiner 1986). How people make causal

inference has an impact on how they see the world (Heider 1958). For example, when students fail in an exam, he can blame it on himself for not working hard enough or on the teacher for designing an extreme difficult exam (locus of causality: internal or external). If he blames the failure on himself, he is more likely to try harder next time. However, if he blames it on the teacher (which he has no control over), he is not likely to make extra efforts next time to achieve better. While attribution can be classified into three dimensions, locus, stability and controllability, stability and controllability are most relevant attributional characteristics in service failure.

In a product failure situation, it has been suggested that both controllability and stability can affectcustomer’ssatisfaction (Oliver and DeSarbo 1988) and beliefs that customers deserve apologies and other compensations (Folkes 1984; Kelley et al. 1993) and negative word-of-mouth (Richins 1983). These attributions should

influencecustomers’reaction to aservicefailurein alikewisemanner.Customers who feel the service could have prevented the failure from happening (controllability) will be more angry (Blodgett et al. 1993).Customers’beliefaboutfrequent

occurrence of a service failure will lead to dissatisfaction. In the following two sections, the details and previous empirical studies which supported this argument will be presented.

Controllability Attribution of the Service Failure

When the cause of the service failure is controllable, customers are more likely feel irate (Folkes 1984). When a service fails, compared to uncontrollable failures, customers are more likely to feel that the reason was that the firm should be responsible because the firms could have expended effort to prevent the failures from happening. Therefore, the same level of recovery efforts will lead to lower customer

satisfaction when the service failure is more controllable (Hess Jr. et al. 2003). In other words, when service failures are controllable, customers are more likely to perceivethefailureasthefirm’smistakeand,therefore,haveahigherexpectation of service recovery. Otherwise, consumers might engage in counterfactual thinking imagining that they would not have to suffer if service providers were willing to expend the efforts (McColl-Kennedy and Sparks 2003). It is easier for customers to forgiveemployeeswho arepowerlessto producecustomers’desired results than employees who could have done it if they had wanted to (Hui and Toffoli 2002). Kelley, Hoffman and Davis (1993) found that most failures with a high rating are controllable. When the failures are controllable, consumers tend to be more harsh in terms of their evaluation of recovery. Therefore, failures are harder to recover from when they are controllable.

Using a sample of travelers, Bitner (1990) conducted an experiment and empirically demonstrated that customers are not as dissatisfied when a pricing error made by a travel agent is perceived to be uncontrollable compared to when it is perceived to be controllable. Oliver (2000) also confirmed this point of view in his essay about customer satisfaction with service. He claims that while service failure is distressing, customers can be further enraged if they feel service provider could have controlled and prevented the service failure.

Blodgett, Granbois, and Walters (1993) suggest that it is the interaction between controllability and stability that affect repatronage intention negative word-of-mouth. That is, it suggests that only when service failures are perceived as controllable AND stable, negative word-of-mouth and exit are more likely to occur. When customers perceive the products as controllable but not stable (or stable but not controllable), they tend to engage in somewhat less negative word-of-mouth and exit. Although Blodgett, Granbois, and Walters (1993) suggest that the effect of

controllability depends on whether failures are stable or not. Most of empirical studies still support the direct negative effect of failure controllability on customer

satisfaction. Hence, the forgoing leads to the following hypothesis:

H4: The higher the controllability attribution about the service failure, the

lower the level of customer satisfaction.

Stability Attribution of the Service Failure

Stability attributions refer to customer perceptions of the likelihood of

experiencing the failures in the future (Swanson and Kelley 2001). When customers attribute service failure to less stable causes, they take the infrequency into

providers’knowing how to correctthefailure(Hess Jr. et al. 2003). Customers usually have higher expectations about service recovery when service failures are more stable. That is, they are harder to be pleased if they feel same mistake is being made repeatedly. They would expect a service provider to know what to do to compensate them if they have extensive experience in dealing with the same

service failure. For example, overbooking is a common issue in the airline industry. Therefore, when it does occur, customers would expect the service provider to know what to do in order to compensate them. However, if they do not know, customers are likely to feel that they are either incompetent or lack sincerity to solve the problem. Kelley, Hoffman, and Davis (1993) demonstrate that for more stable failures, the effectiveness of recovery strategies are reduced. Blodgett, Granbois, and Walters (1993) concludethatcustomers’negativeword-of-mouth and repatronage intention are positively associated with stability of service failure, especially when the failure is controllable.

Smith and Bolton (1998) also reported negative effect of stability attribution on customer cumulative satisfaction. For example, if a customer believes a hotel tend to overbook very often, they will be less satisfied when they do encounter room unavailability problem.

H5: The higher the stability attribution about the service failure, the lower the

level of customer satisfaction.

Theoretical Framework

Summarizing the hypotheses postulated in the previous section, the theoretical framework can be illustrated as below.

Choice Fairness Perception Customer Satisfaction with Service Recovery H1 H2 H3 Attribution of Controllability Attribution of Stability H4 Service Importance H5

Figure.1. Theoretical Framework

METHODOLOGY

Experimental Design and Procedures

Participants. Three hundred fourteen students from in a large university in the

Midwest were recruited to complete a paper-and- pencil questionnaire. The median age of respondents was 21 years. A little over half of the sample (55.9%) was male. More than half of the sample was Caucasian. The next largest ethnic group was Asian, 19.8 %.

Procedures. Anexperimentwasconducted to testthestudy’shypotheses.A 2 (choice

vs. no choice) x 2 (high vs. low service importance) between subjects experimental design was employed with choice and importance of the service manipulated.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four experimental conditions. In the questionnaire, subjects were asked to read a scenario depicting a service failure involving a car repair shop, Alpha. The scenarios described a service encounter in which a car repair job was not completed at the promised time, unbeknownst to the customer.

In the high importance scenario, the customer was dropped off at Alpha and needed to attend to an important appointment immediately after picking up the

repaired car. In the low importance scenario, the customer went to pick up the car with a friend (and therefore could have his/her friend take him/her home if s/he could not get the car back on time) and had nothing pending immediately after picking up the car. In the choice condition, customer contact (sales) personnel provided alternative solutions to the customer to rectify the service failure [(a) a 10 % discount on the cost of the repair, (b) a free loaner with no extra cost, and (c) an immediate completion of the service]. In the no choice group, subjects were assigned to a free loaner in the high

importance condition and a 10% discount in the low importance condition (the

rationale for these assigned alternatives is offered in the next section). After reading the scenario, participants were asked to complete a questionnaire concerning their perceptions of choice and control in the consumption experience, as well as their satisfaction with the service recovery and the entire service encounter.

Manipulation Checks. Experimentalsubjects’mean scores for the choice

manipulation checks were significantly different between the choice and no choice conditions (5.2 versus 3.0, t1, 274= 15.8, p < 0.05), but not significantly different

between the high importance and low importance conditions (4.2 versus 4.1, t1, 274

= .69, n.s.). The mean scores for the importance manipulation checks were

t1, 274= 8.0, p < 0.05). However, the mean scores of the importance manipulation

check items were not significantly different between the choice and no choice conditions (4.4 versus 4.5, t1, 274= .76, n.s.). These results indicate that the

manipulations were effective and not confounded by each other. The reliabilities of the two scales employed for the manipulation checks, perceived choice and

importance of the service, were, respectively, .80 and .76, within an acceptable range (Nunally, 1978).

Measures

All multiple-item scales in this study were measured on a 7-point Likert scale, with anchors ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Items were adopted from existing scales, but some modifications were applied to adapt to the particular situations in the scenario (where necessary).

Distributive justice. Distributive justice was measured by adapting the distributive

justice scale developed by Smith, Bolton, & Wagner (1999).“Thestorehas shown adequate flexibility in dealing with my problem”isasampleitem.Cronbach’salpha for the scale was 0.80.

Procedural justice. While procedural justice typically taps many constructs such as

timeliness (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002), opportunity to voice (Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998), and whether customers need to make extra effort to receive the recovery (Blodgett, Hill, and Tax 1997), this study prepares to measure the overall procedural justice perceptions. Therefore, the scale was adapted from Maxham and Netemeyer (2002) and Smith, Bolton and Wagner (1999) and Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran (1998).“Thestorehas shown adequate flexibility in dealing with my problem”isasample item.Cronbach’salphaforthescalewas0.70.

Interactional justice. Interactional justice was measured by adapting the interactional

justice scale developed by Smith, Bolton, & Wagner (1999).“Idid notgetwhatI deservefrom thestore”isasampleitem.Cronbach’salphaforthescalewas0.70.

Stability and Controllability. Russell’s(1982)scaleforattributionsofstability and

attributionsofcontrollability willbeused to measurecustomers’attribution ofservice failure. For both attribution, 7-point semantic differential scales were used.

Satisfaction with Service Recovery. Maxham and Netemeyer’sscale(2002)for

customer satisfaction with service recovery was adapted with minor modification to fitthecurrentcontext.A sampleitem is:“In my opinion,thestoreprovided a satisfactory resolution to theproblem on thisparticularoccasion.”Cronbach’salpha was 0.85.

Realism Check. In order to confirm that the scenarios were realistic, two items were

used to assesssubjects’perception ofrealism.The itemswere(a)“thisstory is

realistic,”and (b)“thisstory reflectswhatmighthappen in therealworld.”Theaverage participants’rating ofrealism was5.5 (with 7 = strongly agree),significantly greater than 4 (neither agree nor disagree) (t1, 275 = 19.5, p < 0.001). This result indicates that participants seemingly perceived the scenarios to be realistic. The average rating of people in the choice and no choice group were, respectively, 5.5 and 5.5, indicating that there is no significant difference between these two groups in terms of the degree to which subjects felt the scenarios were realistic (t1, 274 = 0.4, n.s.). Similarly, there was no significant difference between participants in the high importance and low

importance conditions regarding scenarios realism (t1, 274 = 1.6, n.s.).

RESULTS

H1 posited that, subsequent to a service failure, customers who were offered a choice of service recovery alternatives would perceive a) the outcome, b) the

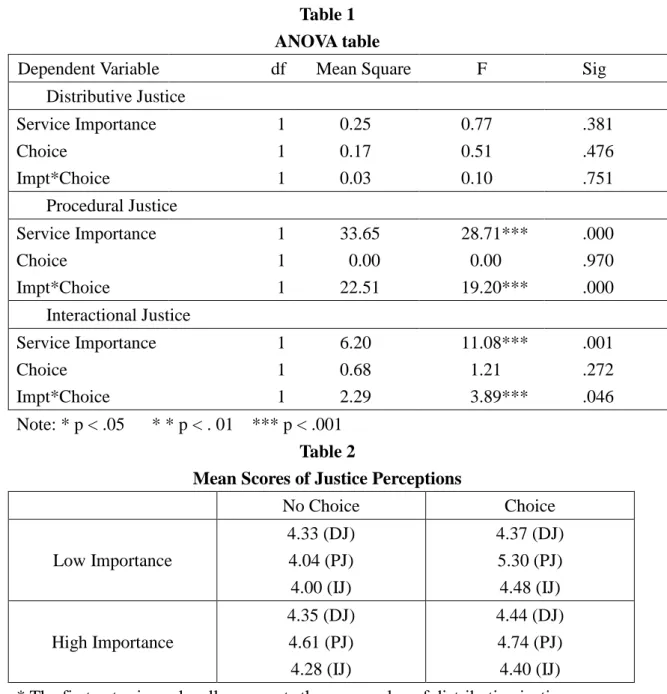

procedure, and c) the interaction with the service provider to be more fair than when not offered a choice. The results suggested that none of the above hypotheses were supported. However, since H2 proposed that there is an interaction between choice provision and service importance, whether choice provision has an effect on customer fair perceptions need to be discussed in the context of service importance. The results suggested that choice provision after service failures and service importance work togetherto determinecustomers’perceptionsofproceduraland interactionaljustice (F1,272= 19.20, p< .001; F1,272= 3.89, p<.005).

According to table 2, it appears that choice provision could only affect customer fairness perceptions only when service importance was low. In addition, judging from Table1,choiceonly increased customers’perceptionsaboutproceduraljusticeand interactional justice when service was less important. It was not found to have an effecton customers’perception ofdistributivejusticeeven when serviceimportanceis low.

When the service importance was high, however, choice provision has little effecton customers’fairnessperceptions.Therefore,H2 was not supported. The effect of choice provision after a service failure was not enhanced when service importance was higher. On the contrary, it was diminished when the service importance increases.

Table 1 ANOVA table

Dependent Variable df Mean Square F Sig

Distributive Justice Service Importance 1 0.25 0.77 .381 Choice 1 0.17 0.51 .476 Impt*Choice 1 0.03 0.10 .751 Procedural Justice Service Importance 1 33.65 28.71*** .000 Choice 1 0.00 0.00 .970 Impt*Choice 1 22.51 19.20*** .000 Interactional Justice Service Importance 1 6.20 11.08*** .001 Choice 1 0.68 1.21 .272 Impt*Choice 1 2.29 3.89*** .046 Note: * p < .05 * * p < . 01 *** p < .001 Table 2

Mean Scores of Justice Perceptions

No Choice Choice Low Importance 4.33 (DJ) 4.04 (PJ) 4.00 (IJ) 4.37 (DJ) 5.30 (PJ) 4.48 (IJ) High Importance 4.35 (DJ) 4.61 (PJ) 4.28 (IJ) 4.44 (DJ) 4.74 (PJ) 4.40 (IJ) * The first entry in each cell represents the mean value of distributive justice score followed by the mean score of procedural justice score. The last entry is the mean score of interactional justice.

H3 argued that when customers perceived the a) outcome b) procedures and c) the service provider to be fairer with regard to recovering the service failure, their satisfaction with service recovery would be enhanced. The results from Table 3 corroborate these hypotheses. When simultaneously entered in a regression equation, all three dimensions of justice were found to have unique contribution to explaining customer satisfaction with service recovery (the ß coefficients for distributive, procedural, and interactional justice were respectively ß1= 0.564, p<.001; ß2= 0.159,

hypothesis 3.

The regression analysis showed that stability and controllability were not significant indicatorsofcustomersatisfaction with recovery (β = 0.011 and -0.012 respectively, n.s.).Therefore,itsuggested thatwhen considered simultaneously with customers’ different dimensions of fairness perceptions, customer attribution did not contribute to influence customer satisfaction with service recovery. Therefore, H4 and H5 were not supported.

Table 3

Results of Regression Analysis Examining the Impact of Customer Attribution and Justice Perceptions on Customer Satisfaction with Recovery

Variables Parameter Estimate Standards Error ß T-Values p-value Stability .020 .057 .011 .350 .726 Controllability -.022 .057 -.012 -.382 .703 Distributive Justice .655 .059 .582 11.117 .000 Procedural Justice .185 .056 .156 3.324 .001 Interactional Justice .232 .062 .200 3.741 .000 R2= .762 Adjusted R2= .757 F5, 263 = 168.18*** Note: * p < .05 * * p < . 01 *** p < .001 研究自評: 近來,國外行銷學者開始了解公平知覺對消費者的知覺或是滿意度有著重要的影 響,紛紛從事這方面的研究,所以,這方面研究的貢獻應能增加行銷學者對於公 平知覺的了解。本研究驗證了提供消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權對於不同構面 之消費者公平知覺所產生的影響。具體說來,消費者之公平知扮演中介變項的角 色,提供消費者對服務補救措施之選擇權經由提高消費者之公平知覺而進一步提 高顧客對於服務補救措施之滿意度。另外,本研究除了考慮公平知覺對於顧客對 於服務補救措施之滿意度的影響之外,亦同時檢驗顧客對服務疏失歸因(e.g., 對於疏失穩定性及疏失是否是為廠家所能控制)對於顧客對於服務補救措施之滿 意度的影響,研究結果指出,當控制公平認知之影響時,顧客對服務疏失的歸因 並未對顧客對於服務補救措施之滿意度造成顯著的影響。所以,本研究應達成了 預期的期望

Reference:

Anderson, Eugene W. and Mary W. Sullivan (1993), "The antecedents and

consequences of customer satisfaction for firms.," Marketing Science, 12 (2), 125-43.

Benartzi, Shlomo and Richard H. Thaler (2002), "How Much Is Investor Autonomy Worth?," Journal of Finance, 57 (4), 1593-616.

Berry, Leonard L. (1995), "Relationship Marketing of Services--Growing Interest, Emerging Perspectives.," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23 (4), 236.

Bies, Robert J. and Joseph S. Moag (1986), "Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness," Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 1 (43-55).

Bitner, Mary Jo (1990), "Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surrounding and employee responses," in Journal of Marketing Vol. 54: American Marketing Association.

Bitner, Mary Jo, Bernard H. Booms, and Mary Stanfield Tetreault (1990), "The service encounter: Diagnosing favorable and Unfavorable Incidents," Journal of Marketing, 54 (1), 71-84.

Blodgett, Jeffrey G., Donald H. Granbois, and Rockney G. Walters (1993), "The Effects of Perceived Justice on Complainants' Negative Word-of-Mouth Behavior and Repatronage Intentions.," Journal of Retailing, 69 (4), 399-428.

Distributive, Procedural, and Interactional justice on Postcomplaint Behavior," Journal of Retailing, 73 (2), 185-210.

Botti, Simona (2004), "Freedom of Choice and Perceived Control: An Investigation of the Relationship between Preference for Choosing and Outcome Satisfaction,"

Doctoral Dissertation, University of Chicago.

---- (2002), "Preference for Control and its Effect on Evaluation of Consumption Experience." Chicago, IL.

Botti, Simona and Sheena S. Iyengar (2003), "The Psychological Pleasure and Pain of Choosing: When People Prefer Choosing at the Cost of Subsequent Well-Being," in Working Paper. Chicago, IL.

Brown, Christie and Fred Feinberg (2002), "How Does Choice Affect Evaluations?," in Advances in Consumer Research Vol. 29. Atlanta, GA: Association for Consumer Research.

Chang, Chia-Chi (2004), "The Effect Of Choice And Perceived Control On Customer Satisfaction: The Psychology Of Service Recovery," Dissertation, Purdue University.

Chernev, Alexander (2001), "The Impact of Common Features on Consumer Preferences: A Case of Confirmatory.," Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (4), 475-183.

Conlon, Donald E. and Noel M. Murray (1996), "Customer Perceptions of Corporate Responses to Product COmplaints: the Role of Explanation," Academy of

Management Journal, 39 (4), 1040-56.

Cropanzano, Russell and Jerald Greenberg (1997), "Progress in Organizational Justice: Tunneling Through the Maze," International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12, 317-72.

Festinger, Leon (1957), A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Folger, Robert (1977), "Distributive and procedural justice: Combined impact of voice and improvement on experienced inequity," Journal of Personality & Social

Psychology, 35 (2), 108-19.

Folger, Robert, David Rosenfield, Janet Grove, and Louise Corkran (1979), "Effects of "voice" and peer opinions on responses to inequity," Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 37 (12), 2253-61.

Folkes, Valerie S. (1984), "Consumer Reactions to Product Failure: An Attributional Approach," Journal of Consumer Research, 10, 398-409.

Fornell, Claes and Birger Wernerfelt (1987), "Defensive Marketing Strategy by Customer Complaint Management: A Theoretical Analysis.," Journal of Marketing Research, 24 (4), 337-46.

Goodwin, Cathy and Ivan Ross (1992), "Consumer Responses to Service Failures: Influence of Procedural and Interactional Fairness Perceptions," Journal of Business Research, 25, 149-63.

Gronroos, Christian (1988), "Service Quality: The Six Criteria Of Good Perceived Service," Review of Business, 9 (3), 10.

Hart, Chistopher W. L. , James L. Heskett, and W. Earl Sasser (1990), "The Profitable Art of Service Recovery.," Harvard Business Review, 68 (4), 148-56.

Heider, Fritz (1958), The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York, NY: Wiley.

Hess Jr., Ronald L. , Shankar Ganesan, and Noreen M. Klein (2003), "Service Failure and Recovery: The Impact of Relationship Factors on Customer Satisfaction.," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31 (2), 127.

Hoffman, K. Douglas, Scott W. Kelley, and Holly M. Rotalsky (1995), "Tracking Service Failures and Employee Recovery Efforts.," Journal of Services Marketing, 9 (2/3), 49-61.

Hui, Michael K. and Roy Toffoli (2002), "Perceived Control and Consumer

Attribution for the Service Encounter.," in Journal of Applied Social Psychology Vol. 32.

Keaveney, Susan M. (1995), "Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study.," Journal of Marketing, 59 (2), 71-82.

Kelley, Scott W., K. Douglas Hoffman, and Mark A. Davis (1993), "A Typology of Retail Failures and Recoveries.," Journal of Retailing, 69 (4), 429-52.

Lind, Ellen A. and Tom R. Tyler (1988), The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. New York, NY: Plenum.

Lipton, David (2000), "Now hear this...Customer complaints are not bad if viewed as business-building occasions.," Nation's Restaurant News, 34 (35), 30.

Manogran, Paramasivam, Joseph Stauffer, and Edward J. Conlon (1994), "Leader-Member Exchange as a Key Mediating Variable Between Employees Perceptions of Fairness and Organizational Citizenship Behavior," in The annual meeting of the Academy of Management. Dallas, TX.

Masterson, Suzanne S., Kyle Lewis, Barry M. Goldman, and Susan M. Taylor (2000), "Integrating Justice and Social Exchange: The Differing Effects of Fair Procedures and Treatment on Work Relationships," Academy of Management Journal, 43 (4), 738-48.

Maxham III, James G. and Richard G. Netemeyer (2002), "Modeling customer perceptions of complaint handling over time: the effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent.," in Journal of Retailing Vol. 78: Elsevier Science Publishing Company, Inc.

Maxham, James G. and Richard G. Netemeyer (2002), "Modeling customer perceptions of complaint handling over time: the effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent.," Journal of Retailing, 78 (4), 239-52.

McColl-Kennedy, Janet R. and Beverley A. Sparks (2003), "Application of Fairness Theory to Service Failures and Service Recovery.," in Journal of Service Research Vol. 5: Sage Publications Inc.

Moorman, Robert H. (1991), "Relationship Between Organizational Justice and Organizational Citizenship Behaviors: Do Fairness Perceptions Influence Employee Citizenship?," Journal of Applied Psychology, 76 (6), 845-55.

O'Connor, Gina Colarelli and George J. Siomkos (1994), "The need for control in the service sector.," Journal of Applied Business Research, 10 (3), 105.

Oliver, Richard L. (2000), "Customer Satisfaction with Service," in Handbook of services marketing & management, Teresa A. Swartz and Dawn Iacobucci, Eds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Oliver, Richard L. and Wayne S. DeSarbo (1988), "Response Determinants in Satisfaction Judgments.," Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (4), 495-507.

Reichheld, Frederick F. and Junior Sasser, W. Earl (1990), "Zero defections: Quality comes to services.," Harvard Business Review, 68 (5), 105-11.

Richins, Marsha L. (1983), "Negative Word-of-Mouth by Dissatisfied Consumers: A Pilot Study.," Journal of Marketing, 47 (1).

Ries, Harry T. (1986), "Levels of Interest in the Study of Interpersonal Justice," in Justice in Social Relations, Hans W. Bierhoff and Ronald L. Cohen and Jerald Greenberg, Eds. New York: Plenum Press.

Schneider, Benjamin and David E. Bowen (1999), "Understanding Customer Delight and Outrage.," Sloan Management Review, 41 (1), 35-45.

Smith, Amy K. and Ruth N. Bolton (1998), "An Experimental Investigation of Customer Reactions to Service Failure and Recovery Encounters: Paradox or Peril?," Journal of Service Research, 1 (1), 65-81.

Smith, Amy K., Ruth N. Bolton, and Janet Wagner (1999), "A Model of Customer Satisfaction with Service Encounters Involving Failure and Recovery.," Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (3), 356-72.

Swanson, Scott R. and Scott W. Kelley (2001), "ATTRIBUTIONS AND

OUTCOMES OF THE SERVICE RECOVERY PROCESS.," Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 9 (4), 50.

Tax, Stephen S. and Stephen W. Brown (1998), "Recovering and Learning from Service Failure.," Sloan Management Review, 40 (1), 75-88.

Tax, Stephen S., Stephen W. Brown, and Murali Chandrashekaran (1998), "Customer Evaluations of Service Complaint Experiences: Implications for Relationship

Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 62 (2), 60-76.

Thibaut, John W. and Laurens Walker (1975), Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Tyler, Tom. R., Peter Degoey, and Heather Smith (1996), "Understanding Why the Justice of Group Procedures Matters: A Test of the Psychological Dynamics of the Group Value Model," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70 (May), 913-30.

Weiner, Bernard (1986), An Attributional Theory of Motivation and Emotion. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Zemke, Ron and Chip Bell (1990), "Service Recovery: Doing It Right the Second Time," Training, 27 (6), 42.