____________________________________________

Chia-Pin (Simon) Yu, Ph.D. Candidate

Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Studies Indiana University Bloomington, USA Email: yu8@indiana.edu

H. Charles Chancellor, PhD.

Assistant Professor Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Studies Indiana University Bloomington, USA Email: hcchance@indiana.edu

Shu Tian Cole, PhD.

Associate Professor Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Studies Indiana University Bloomington, USA Email: colest@indiana.edu

EXAMINING THE EFFECTS OF TOURISM IMPACTS ON

RESIDENT QUALITY OF LIFE : EVIDENCE FROM

RURAL MIDWESTERN COMMUNITIES IN USA

Chia-Pin (Simon) Yu

Indiana University Bloomington, USA

H. Charles Chancellor

Indiana University Bloomington, USA

Shu Tian Cole

Indiana University Bloomington, USA

ABSTRACT : Tourism impacts studies have identified three major types

of positive-negative tourism impacts that dynamically change residents’ life experiences and their evaluation of tourism development. This study examines three specific impacts, perceived social costs, environmental sustainability, and perceived economic benefit, to determine their effects on resident perceived quality of life. The results indicate that the social cost dimension has no significant effect on resident quality of life, however both environmental sustainability and perceived economic benefit dimensions significantly affect resident quality of life.

INTRODUCTION

McCool and Martin (1994) indicated that the purpose of tourism development should be to increase the quality of life (QOL) for local residents, and many communities look to tourism development for this very purpose. The underlying premise is that tourism brings economic benefits to communities, primarily through increased job opportunities and tax revenues. However tourism development may also produce a variety of negative impacts such as crowding, traffic congestion, crime, pollution, environmental degradation, and increased cost of living that may harm residents’ quality of life. Researchers have revealed a connection between residents’ quality of life and tourism development and have found that several factors influence resident quality of life including, type and number of tourists, type and number of residents, social exchange relations, social representations, and type of tourism development may influence residents’ quality of life (Carmichael, 2006). Resident-related variables (e.g. length of residence, distance of tourism center from the residents’ home, resident involvement in tourism decision-making, etc.) may affect residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts (Chancellor, Yu, & Cole, 2011; Lankford & Howard, 1994). Numerous researchers have studied resident attitudes toward tourism impacts and some studies emphasized the relationship between impacts and resident quality of life (Allen & Beattie, 1984; Allen, Long, & Perdue, 1987; Roehl, 1999; Perdue, Long & Kang, 1999; Vargas-Sanchez, Plaza-Mejía, & Porras-Bueno, 2008; Ko, & Stewart, 2002). In addition, studies have examined the effects of resident characteristics, community characteristics, perceived personal benefits, positive tourism impacts and negative tourism impacts on resident quality of life (Roehl, 1999; Perdue, Long & Kang, 1999; Vargas-Sanchez, Plaza-Mejía, & Porras-Bueno, 2008; Ko, & Stewart, 2002).

Resident quality of life and satisfaction are important not only for the residents but also for tourism development investors and stakeholders. Resident dissatisfaction can lead to visitors not being welcomed by residents, which jeopardizes tourists having a positive experience. Therefore, the tourism industry relies on the host society’s hospitality and goodwill, which suggests that resident dissatisfaction, can become a liability for the local tourism industry (Gursoy, Jurowski, & Uysal, 2002). Destination community residents who support the tourism industry tend to be friendlier toward tourists, providing a more positive experience for the visitors, which may influence both revisit intentions and word-of-mouth recommendations. For a successful tourism industry, the goodwill of local residents must be considered along with more typical concerns such as successfully operating a tourist oriented business or organization (Jurowski, 1994). Therefore understanding residents’ quality of life from a social, environmental, and economic impact perspective can be very instructive. This study used the validated sustainable tourism attitudes scale (SUS-TAS) to examine economic, social, and environmental tourism impacts on residents’ perceived quality of life (Yu, Chancellor, & Cole, 2009). This information may be useful to regional, local, and destination stakeholders, in addition to tourism planners and policy makers.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Resident quality of life and tourism impacts

Quality of life (QOL) has become a topic of broad discussion in recent years (Andereck et al., 2007). The main purpose of a QOL study in a community is to understand residents’ well-being from both an objective perspective that is external to the individual such as economic measures (Gross Domestic Product (GDP); income) and a subjective perspective that reflects individual feelings and perceptions. There are some limitations of objective QOL measures in studying community QOL. For example, growth in GDP reflects higher average incomes for a community but if cost-of-living increases more, then residents’ perceived QOL might decline. Subjective QOL provides necessary context since it is emotive, value-laden, and encompasses life satisfaction, feelings of well-being, and beliefs about one’s standard of living (Davidson & Cotter, 1991; Diener & Suh, 1997; Dissart & Deller, 2000; Grayson & Young, 1994; Andereck & Jurowski, 2006; Andereck et al., 2007). Researchers argue that the subjective perspective of QOL is critical to accurately evaluate quality of life (Andereck & Jurowski, 2006; Dissart & Deller, 2000).

Tourism development is often perceived as a possible driver for economic benefits, which will consequently improve resident quality of life. However, a destination experiences a variety of economic, social-culture, and environmental effects. Although it is hoped that the myriad effects will be positive and enhance the residents’ lives, that is not always the case. To more accurately understand tourism’s role in the residents’ quality of life, resident’s perceptions of tourism impacts must be evaluated (Andereck & Jurowski, 2006). Carmichael (2006, p. 116) proposes a conceptual model, which connects tourism development/tourist experience and resident quality of life experiences. This model suggests that tourism impacts directly affect resident quality of life and resident attitudes toward tourism and tourists.

affect residents’ evaluation of tourism (Andereck, 1995; Marcouiller, 1997; Ryan, 1991; Jurowski, 1994). Many communities encourage tourism development because they expect economic benefits in the form of additional increased income, tax revenues, and employment opportunities. However negative economic effects such as an increased cost of living may degrade residents’ quality of life, if residents’ standard of living outweighs their cost of living (Liu & Var, 1986). In addition, economic benefits are not the same as residents’ quality of life. When economic benefits cause deterioration in social or physical environments, residents’ quality of life may decline (Roehl, 1999; Jurowski & Gursoy, 2004). Residents in a tourism destination may be forced to change their habits, daily routines, social beliefs, and values which can lead to psychological tension (Andereck & Jurowski, 2006) and consequently a lower quality of life. Researchers have suggested that negative social consequences of tourism include a loss of resident identity and local culture (Rosenow & Pulsipher, 1979), decline in traditions, increased materialism, increased crime, social conflicts, and crowding (Dogan, 1989). On a positive social note, tourism can encourage an increase and improvement in cultural awareness, facilities and related activities (Brunt & Courtney 1999). This is especially true of unique cultures in danger of disappearing such as the Cajuns in southern Louisiana, USA. Tourism and its associated activities related to music, food, and dance in particular, has enhanced the awareness of and highlighted the Cajun culture (Esman, 1984).

With respect to environmental effects, the tourism industry is considered a relatively clean industry that often brings the improvement of local infrastructure (e.g. roads, utilities), and the protection of environment and wildlife (Liu & Var, 1986). However, tourism may cause significant environmental damage through pollution, habitat destruction, and disruption to wild life (Andereck, 1995). Given the complexity of tourism impacts on resident QOL, current studies have examined factors such as resident characteristics, and positive/negative tourism impacts on resident quality of life.

Empirical studies of tourism impacts on resident quality of life

Researchers have explored factors that directly influence resident quality of life. Allen and colleagues (1988) noted that residents’ perceptions of community life satisfaction vary with the levels of tourism development. They used the community life scales (Allen & Beattie, 1984; Allen, Long, & Perdue, 1987), which grouped 33 community life indicators into seven community life dimensions (public service, formal education, environment, recreation opportunities, economics, citizen involvement and social opportunity, and medical service), and then investigated residents’ perceptions of importance and their satisfaction. Their results suggested that the level of tourism development is related to residents’ perception of community life. Specifically, opportunities for citizen involvement, public services, and environmental concerns were the dimensions most sensitive to changes in tourism development. Their study suggested that tourism impacts influence community life, which relates to resident quality of life.

Roehl’s (1999) study in Nevada identified a relationship among resident characteristics, perceptions of the impacts of gaming, and perceived quality of life. He found that perceived social costs were negatively correlated with QOL, whereas perceived job growth was positively correlated with QOL. In addition, resident demographic characteristics were unrelated to resident perceived quality of life. Perdue, Long and Kang (1999) also reported that demographics did not affect resident quality of life.

Several studies (Ko & Stewart, 2002; Vargas-Sanchez, Plaza-Mejía, & Porras-Bueno, 2009) treated overall community satisfaction as a mediator between tourism impacts and resident support for tourism development. Ko and Stewart proposed and tested a hypothetical model that combined the community life satisfaction construct (Allen, Long, Perdue, & Kieselbach, 1988) and four latent constructs (personal benefits from tourism development, positive perceived tourism impacts, negative perceived tourism impacts, and attitudes for additional tourism development) of resident tourism perceptions and attitudes (Perdue et. al, 1990). They found

that residents’ community satisfaction was related to perceived positive and perceived negative tourism impacts (which included economic, socio-cultural, and environmental impacts) but the path relationship between personal benefits from tourism development and community satisfaction was rejected. Vargas-Sanchez et al. (2009) applied Ko and Stewart’s hypothetical model in Minas de Riotinto, Spain. Their results confirmed the influence of the perception of the positive tourism impacts on the overall community satisfaction, but not of the perception of negative tourism impacts nor personal benefits from tourism development.

In general, it’s recognized that positive-negative tourism impacts relate to resident quality of life/community satisfaction. However, results are mixed regarding the potential for negative tourism impacts’ influence on resident quality of life (Ko & Stewart, 2002; Vargas-Sanchez, et al., 2009). This is an area ripe for further research.. Additionally, positive-negative tourism impacts should be separated to fully understand their effects on resident perceived quality of life. Dyer, and his colleagues (2007) examined five separated factors of tourism impacts (negative socio-economic impact, positive social impact, negative social impact, positive economic impact and positive cultural impact) on resident support for tourism development and found that perceived economic benefits and perceived cultural benefits had significant positive impact on local residents’ support for tourism development. Their work provides a framework for understanding the relationships between separated positive-negative tourism impacts and resident support for tourism development. This study separated positive-negative tourism impacts on resident quality of life to provide a testable framework to understand the mechanism of resident quality of life/community satisfaction. To this end, this study measured resident perceptions of tourism impacts and quality of life. Specifically, the purpose of this research is (1) to capture residents’ perceived quality of life and their perceptions of tourism impacts by using the sustainable tourism attitudes scale (SUS-TAS); and (2) to examine the economic, social, and environmental tourism impacts on residents’ perceived quality of life. This study contributes to a better understanding of tourism development’s role in

the residents’ quality of life and may aid policymakers, and local tourism stakeholders in their desire to balance the needs of residents and tourists.

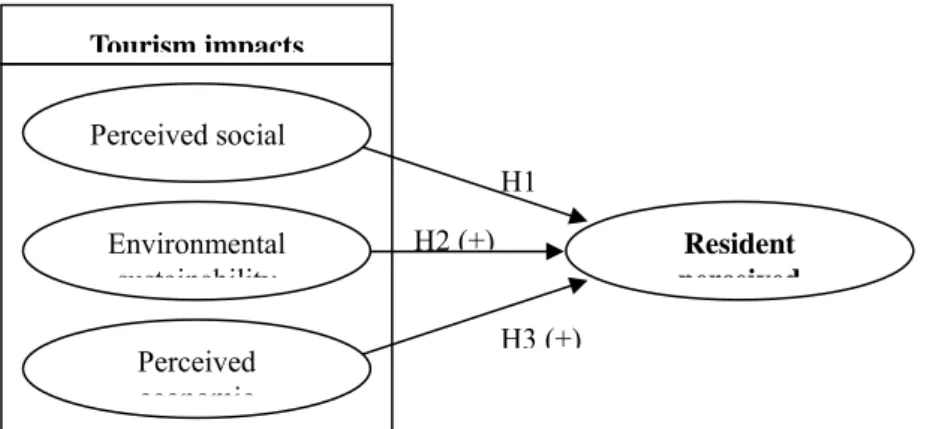

Hypothetical model and research hypotheses

This study investigates three variations of tourism impacts to determine their influence on resident perceived quality of life. Specifically, the hypothetical model (see Figure 1) consists of four latent constructs about tourism impacts and resident quality of life. It suggests three paths of hypotheses to explain the relationships among the four constructs, resident perceived quality of life, perceived social costs, environmental sustainability, and perceived economic benefit. Research hypotheses are as below:

H1: Perceived social costs construct has significantly negative

effects on resident perceived quality of life.

H2: Environmental sustainability construct has significantly

positive effects on resident perceived quality of life.

H3: Perceived economic benefits construct has significantly

positive effects on resident perceived quality of life

.

Figure 1: Hypothetical model and research hypotheses

Resident perceived H1 H2 (+) H3 (+) Perceived economic Environmental sustainability Perceived social Tourism impacts

METHOD

Study site

This study was conducted in Orange County, Indiana, United States. Orange County is located in south central Indiana and had a population of 19,600 people in 2008. Woodworking and furniture manufacturing are major industries in the Orange County economy (Orange County Economic Development Partnership, 2009). Relative to other counties in Indiana, Orange County is not affluent as the annual per capita personal income was USD 28,603 in 2008 which was lower than the state average (USD 34,535) and ranked 76th out of the 92 counties (STATSIndiana, 2009). Thus Orange County looked to diversify and stimulate its economy through increased tourism development, which is a re-emerging industry and becoming a major economic development tool. Traditional attractions include lakes, a ski slope, shopping, a resort and an array of museums. New tourism development includes a refurbished upscale resort, four-star and other lodging, a casino, golf courses, and an indoor/outdoor water park. The newly developed attractions and amenities begin opening in the fall of 2006. Evidence suggests that recent tourism development has provided economic growth to Orange County. Official statistics (STATIndiana, 2009) indicates that Orange County’s average earning per job for the accommodations and food service sector ranks #1 in state. This sector experienced dramatic job growth as the number of workers increased from 950 to 2044 and the average earning per job increased 25% during 2006 and 2007.

Procedures

Survey instruments were mailed to a random selection of 2000 households in Orange County January through April 2007. Using a modified Dillman (2000) Tailored Design technique, each respondent was contacted five times. The questionnaire contained each of the 44

items from the Sustainable Tourism Attitude Scale (SUS-TAS) (Choi and Sirakaya, 2005; Sirakaya et al., 2008) as well as information on the residents’ demographics, perception of quality of life in Orange County. There were 649 usable survey instruments for a response rate of 32.5%.

This study used the revalidated SUS-TAS with 27 items demonstrating adequate overall model fit and the overall statistics for revalidated SUS-TAS model were acceptable, χ2 (303) = 690.9, p = .00, RMSEA = .048, GFI = .92, AGFI = .90, CFI = .97, NFI = .95, NNFI = .97, and SRMR = .045 (Yu, Chancellor, & Cole, 2009). The results supported the construct validity and internal consistency. The revalidated 27-item SUS-TAS identified seven constructs 1) perceived social costs; 2) environmental sustainability; 3) long-term planning; 4) perceived economic benefits; 5) community-centered economy; 6) ensuring visitor satisfaction; and 7) maximizing community participation (Yu, Chancellor, & Cole, 2009). Sirakaya, Ekinci, and Kaya (2008) suggested that researchers could tailor SUS-TAS constructs to fit their research agenda depending on the research purpose because of sufficient evidence of scale reliability and validity. Following their suggestion, authors adopted three constructs - perceived social costs, environmentally sustainability, and perceived economic benefits - of SUS-TAS to measure residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts. The perceived social costs construct contained items pertaining to the potential disruption of residents’ quality of life, including overcrowding, overuse of recreational resources, and the fast growth of tourism development. The environmental sustainability construct included five items: 1) biodiversity protection; 2) wildlife and natural habitat protection; 3) protection of the natural environment for the future; 4) promotion of positive environmental ethics; and 5) development that was in harmony with the natural environment. The perceived economic benefits construct contained four items: 1) tourism’s economic contribution to the community; 2) economic contribution to other than just tourism related businesses; 3) ability to bring in new income; and 4) ability to generate substantial tax revenues. The tourism impacts of perceived social costs, environmental

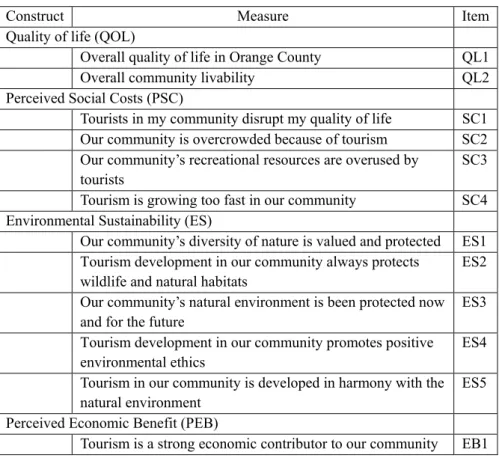

sustainability, and perceived economic benefits were measured on a five-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Undecided, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strong Disagree). Quality of life was measured in subjective dimensions, which reflect individual feelings and perceptions. According to Dissart and Deller (2000), subjective measures are critical to accurately evaluate community quality of life. Therefore, two measures, overall quality of life and overall community livability (Wilkin, 2006), were used to measure residents’ perception of quality of life. A five-point scale (1 = Very Poor, 2 = Poor, 3 = Fair, 4 = Good, 5 = Very Good) was used to measure residents’ perceptions of quality of life. Table 1 indicates constructs and measurements in this study.

Table 1: List of constructs and measurements

Construct Measure Item Quality of life (QOL)

Overall quality of life in Orange County QL1 Overall community livability QL2 Perceived Social Costs (PSC)

Tourists in my community disrupt my quality of life SC1 Our community is overcrowded because of tourism SC2 Our community’s recreational resources are overused by

tourists

SC3 Tourism is growing too fast in our community SC4 Environmental Sustainability (ES)

Our community’s diversity of nature is valued and protected ES1 Tourism development in our community always protects

wildlife and natural habitats

ES2 Our community’s natural environment is been protected now and for the future

ES3 Tourism development in our community promotes positive

environmental ethics

ES4 Tourism in our community is developed in harmony with the natural environment

ES5 Perceived Economic Benefit (PEB)

Tourism benefits other than just tourism industries in our community

EB2 Tourism brings new income to our communities EB3 Tourism generates substantial tax revenues for our local

government

EB4

Data Analysis

This study tested the hypothetical model by using structural equation modeling technique. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is a technique that can simultaneously estimate the relationships between observed and latent variables (the measurement model), as well as the relationships among latent variables (the structural model). SEM is a method that has gained popularity because it combines confirmatory factor analysis and regression analysis to model a variety of psychological, sociological, and other relationships (Lindberg & Johnson, 1997).

In this study, the hypothetical model includes a measurement model and a structural model. Burt (1976) stated that simultaneous estimation of measurement and structural parameters could produce confounding interpretations. In addition, Anderson and Gerbing (1988) argued, “…much is to be gained from separate estimation and re-specification of the measurement model prior to the simultaneous estimation of the measurement and structural sub-models.” Byrne (2009, p.164) also suggested that the measurement model has to be tested first for validity before making any attempt to evaluate the structural model. Thus a two-step procedure was used to assess Orange County residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts and quality of life: 1) validating the measurement model; and 2) testing the structural model. To validate the measurement model, the four latent constructs (quality of life, perceived social costs, environmental sustainability, and perceived economic benefits) were tested for overall model fit, reliability, and validity. In the second step, the hypotheses were tested. The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) technique was used for model fit, reliability, validity, and

testing hypotheses. Data was stored and analyzed using the SPSS 16.0 and Analysis of Moment Structure (AMOS, ver. 17.0) software packages.

This study primarily used a CFA technique for analyzing data, due to its ability to test a particular factor structure. Whereas the hypothetical model was constructed in advance, CFA can be a satisfactory technique for a model with specified latent variables and observed variables (Bollen, 1989). For the measurement model, CFA using the maximum likelihood (ML) method was used to test reliability and validity in both item and construct levels. A 15-item, 4-dimensional (quality of life, perceived social cost, environmental sustainability, and perceived economic benefit) model was estimated to identify the dimensions of the hypothetical model. Goodness-of-fit, using chi-square (χ2), examined the overall fit of the model. Because the χ2 statistic is dependent on sample size, its use is limited in most empirical research (Byrne, 1994), and therefore, a wide variety of other fit indexes which are independent of sample size have been developed (Marsh, Balla, & McDonald, 1988; Hu & Bentler, 1998). Several indices were calculated for this study including the goodness of fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI), non-normed fit index (NNFI), comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). For GFI, NFI, NNFI, and CFI indices, values greater than .95 have served as a rule of thumb for acceptable fit. The RMSEA value should be less than .06 and the SRMR value should be less than .09 to be considered as an acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

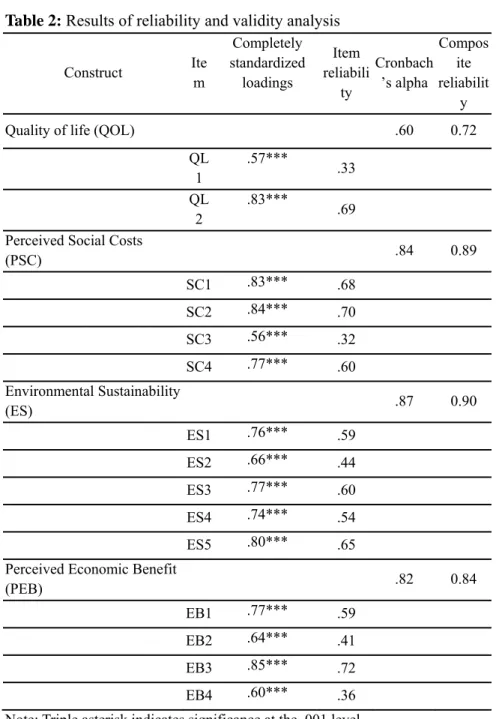

Scale validation

The overall fit of the measurement model was χ2 (84) = 257.91 (p=.000); GFI = 0.95; NFI = 0.94; NNFI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; SRMR = .044; and RMSEA = .057. The results indicated that the measurement model had an acceptable overall model fit.. Fornell and Larcker (1981) argued that each item reliability estimate should exceed .50, and most did as they ranged from 0.33 to 0.72 (see Table 4). Five item reliabilities were lower than .50, which could be due to item wording redundancy (Netemeyer, Bearden, & Sharma, 2003). Whereas each low reliability item was significant to its construct, these items did not jeopardize the integrity of the results and were retained for construct consistency.

Internal consistency (construct reliability) was determined using two different techniques. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from .60 to .87 (see Table 2). All latent constructs exhibited a moderately strong (higher than .70, Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) correlation except quality of life. However, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is a function of number of items, meaning a lower number of items may lead to lower coefficient. Nunnally (1978) indicated that in general the larger the number of items in a scale, the more reliable the scale. Therefore, the lower Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for quality of life may have been caused by there only being two items in the construct. As a result, further construct reliability was examined by using a formula provided by Bagozzi (1980). Whereas a latent construct comprises several items, Bagozzi’s formula generates the composite value for checking latent construct reliability in particular. The thresholds for composite reliability value have been recommended to be at least .60 (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). The composite reliability of all four constructs exceeded the recommended minimum level (from .72 to .90). Overall the variables were found to be internally consistent. Details on the properties of the measurements are provided in

Table 2.

Table 2: Results of reliability and validity analysis Construct Ite m Completely standardized loadings Item reliabili ty Cronbach ’s alpha Compos ite reliabilit y

Quality of life (QOL) .60 0.72

QL 1 .57*** .33 QL 2 .83*** .69 Perceived Social Costs

(PSC) .84 0.89 SC1 .83*** .68 SC2 .84*** .70 SC3 .56*** .32 SC4 .77*** .60 Environmental Sustainability (ES) .87 0.90 ES1 .76*** .59 ES2 .66*** .44 ES3 .77*** .60 ES4 .74*** .54 ES5 .80*** .65

Perceived Economic Benefit

(PEB) .82 0.84

EB1 .77*** .59

EB2 .64*** .41

EB3 .85*** .72

EB4 .60*** .36

Convergent validity can be assessed by determining whether the estimated factor loading of each indicator is significant on its underlying construct (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). As shown in Table 2, all confirmatory factor loadings were statistically significant (p<.001). Additionally, average variance extracted (AVE) was calculated for convergent validity. As shown in Table 3, the AVEs of latent constructs were greater than .50, so the convergent validity concerns of the scales were satisfied (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Bagozzi & Yi, 1988). To establish discriminant validity, authors adopted a method that compares squared correlation of any of two constructs with AVE values (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Specifically, discriminant validity is established when the AVE for each construct is greater than the square of the correlation between the constructs. The results supported the criterion above. Therefore, it can be considered that the scale possessed discriminant validity. The overall CFA model fit, reliability, and validity tests in both item and construct levels demonstrated that the measurement model operated adequately, and the results supported the use of these observed variables. The four-construct structure served as the measurement model for the hypothetical model.

Table 3: Correlations and average variances extracted (AVE).

QOL PSC ES PEB

QOL 0.52

PSC -.205*** 0.66

ES .285*** -.500*** 0.65

PEB .272*** -.556*** .463*** 0.58 Note 1: Triple asterisk indicates significance at the .001 level

Note 2: Diagonal values represent AVEs.

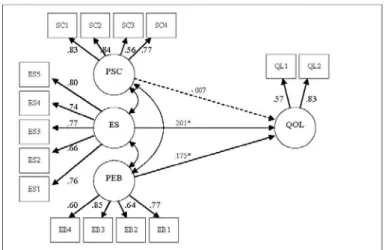

Testing structural model (Hypothetical model evaluation)

After identifying the resident’s perceptions of tourism impacts from perceived social costs, environmental sustainability, and economic benefit aspects, influence of these perceptions on residents’ quality of

life for tourism development was assessed. Due to no item being eliminated in the process of reliability and validity testing, the overall fit of the hypothetical model remained the same as CFA model fit. It was χ2 (84) = 257.91 (p=0.00); GFI = .95; NFI = .94; NNFI = .95; CFI = .96; SRMR = .044; and RMSEA = .057. The results indicated that the hypothetical model is acceptable. Although perceived social costs have negative effects on resident quality of life, the relationship is not significant. The first hypothesis (i.e., perceived social costs have negative effects on resident quality of life) was rejected; t = -.107 (p=.915), β = -.007. The second hypothesis (i.e., environmental sustainability has significantly positive effects on resident quality of life) was supported; t = 3.091 (p<.01), β = .201. The third hypothesis (i.e., perceived economic benefits have significantly positive effects on resident quality of life) was supported; t = 2.247 (p<.05), β = .175. Details on the properties of the hypothetical model are provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Standardized estimated hypothetical model.

Note 1: Dashed line indicates the path that is not significant at .05 level.

significantly negative effects on resident quality of life (H1).

Resident quality of life was not affected by residents’ perceived

social costs. This finding is inconsistent with the other researchers’

findings on negative social impacts toward community

satisfaction/resident quality of life (Jurowski & Gursoy, 2004;

Roehl, 1999; Ko & Stewart, 2002). This finding could be because

tourism development in Orange County was in the initial

development stage, so residents are anticipating positive effects

and they may have demonstrated a higher tolerance toward tourism

induced social costs. Additionally, there are typically less social

costs in the initial tourism development context.

Further evidence indicated that more than half (53.3%) of the

respondents enjoy meeting and interacting with tourists. Doxey

(1975) suggested that residents’ attitude becomes more negative

(from euphoria to annoyance) through the tourism destination

growth cycle. Specifically, he stated that in initial tourism

development stages residents are excited or euphoric about the

anticipated benefits. As the newness of tourism and tourists wears

off and if the anticipated benefits are not realized, the euphoria

diminishes and residents view tourists and tourism development

less positively. In accordance with Doxey’s model, it can be

surmised that residents may be in the “euphoria” stage. The

euphoria psychological state may moderate residents’ perceptions

of negative tourism impacts, so residents perceived less social

costs. In addition, more than half (55.6%) of the respondents

reported that they “rarely” interact with tourists, which may

indicate there are a limited number of visitors during this early

stage of tourism development.

may be diminished when tourism develops beyond a threshold

(Butler, 1980; Allen, Long, Perdue, & Kieselbach, 1988; Perdue,

Long, & Kang, 1999). In the case of this study, the limited number

of tourists may have resulted in residents’ perceiving few social

costs, which were not detrimental to resident quality of life.

Additionally, if residents are more aligned with Doxey’s (1975)

euphoria stage, they may have a higher tolerance for tourists and

tourism, which would result in a higher carrying capacity in terms

of social costs.

Results support that environmental sustainability has

significantly positive effects on resident quality of life (H2).

Previous studies suggested economic impacts and environmental

impacts are related to community satisfaction (Roehl, 1999;

McCool & Martin 1994; Perdue et al., 1990; Ko & Stwart, 2002;

Vargas-Sanchez et al, 2009). Results also supported the idea that

perceived economic benefits from tourism have significant

positive effects on resident quality of life (H3). Therefore, this

study’s results coincide with those found in the literature.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

In this study, the quality of tourism experiences for residents in

Orange County was measured by residents’ perceptions of how

tourism affected their quality of life. The main purpose of this

research was to examine the path relationships between perceptions

of social impacts, environmental impacts and economic impacts, and

resident perceived quality of life. This research captured residents’

perceptions of social, environmental, and economic tourism impacts

with the SUS-TAS. Drawing on the literature, a theoretical model was

proposed and examined, through a structural equation modeling

approach. This study found that resident perceived quality of life was

closely related to “environmental sustainability” and “perceived

economic benefits.” The results were consistent with current tourism

impact toward quality of life literature, in that economic impacts and

environmental impacts are related to community satisfaction/quality

of life (Roehl, 1999; McCool & Martin 1994; Perdue et al., 1990; Ko

& Stewart, 2002; Vargas-Sanchez et al, 2009). Furthermore, findings

showed that perceived social costs had no significant effect on

resident quality of life. This result could be because the study was

conducted during the initial phases of intensive tourism development,

which resulted in 1) residents being in a euphoric state toward

tourism development which moderated negative social impacts, and 2)

there being a limited number of tourists, which would support the

idea that the destination’s carrying capacity was not reached (Butler,

1980; Allen, Long, Perdue, & Kieselbach, 1988; Perdue, Long, &

Kang, 1999). This study benefits tourism practitioners on knowing

tourism’s role and influences on quality of life from residents’

perspective in the early stages of tourism development.. When

residents’ quality of life is enhanced through tourism their reaction to

tourism development and tourists tend to be receptive and friendly,

which provides a better tourist experience, and may lead to repeat

visits and positive word of mouth advertising.

The major contributions of this study are; 1) its extension of

SUS-TAS into a resident quality of life study; and 2) its empirical

examination of three types of tourism impacts on resident perceived

quality of life in the Orange county tourism development context.

Most important, this study demonstrates a useful framework for

monitoring residents’ experiences with tourism development. Tourism

researchers and practitioners could adopt this framework to monitor

tourism impact changes on resident perceived quality of life across

tourism development stages.

With respect to future research, researchers can study other

tourism impacts dimensions such as positive/negative environmental,

positive/negative social, or positive/negative economic effects on

residents’ perceived quality of life across tourism development stages

of destinations. Additionally, this study is a baseline study, which

could be useful for future comparisons. Researchers suggest that a

longitudinal study in a single destination is a preferable methodology

for theory testing and developing (Getz, 1994; McCool & Moisey,

1996; Lee & Back, 2003). Future iterations of this study would allow

tourism officials to better understand and monitor the changes of

tourism impacts and aid researchers in theory development.

REFERENCES

Allen, L. R., & Beattie, R. (1984). The role of leisure as an indicator of overall satisfaction with community life. Journal of Leisure

Research, 16(2), 99–109.

Allen, L. R., Long, P. T. and Perdue, R. R. (1987). Satisfaction in Rural Communities and the Role of Leisure, Leisure Today, April, 5-8. Allen, L. R., Long, P. T., Perdue, R. R, & Kieselbach, S. (1988). The

impacts of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. Journal of Travel Research, 26(1), 16–21. Andereck, K.L. (1995) Environmental consequences of tourism: A

review of recent research. In Linking Tourism, the Environment,

and Sustainability. Annual meeting of the National Recreation and Park Association. General Technical Report No.

INT-GTR-323.

Andereck, K. L., & Jurowski, C. (2006). Tourism and quality of life. In G. Jennings and N. P. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality tourism

experiences, pp. 136-154. Oxford: Elsevier.

Andereck, K. L., Valentine, K. M., Vogt, C. A. & Knopf, R.C. (2007). A Cross-cultural Analysis of Tourism and Quality of Life

Perceptions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 15(5), 483-502. Anderson, J. C. & Gerbing D. W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling

in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-step Approach.

Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–23.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1980). Causal models in marketing. New York: Wiley. Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the Evaluation of Structure Equation

Models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74-94.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: Wiley.

Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26, 493-515.

Bulter, R. (1980). The concept of a tourist area cycle of evaluation: Implication for management of resources. Canadian Geographer,

24, 5-12.

Burt, R. S. (1976). Interpretational confounding of unobserved variables in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and

Research, 5, 3-52.

Byrne, B. M. (1994). Structural Equation Modeling with EQS and

EQS/Windows: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Byrne, B. M. (2009). Structural Equation modeling with AMOS: Basic

Concepts, Applications, and Programming. New York: Routledge.

Carmichael, B. A. (2006). Linking quality tourism experiences,

residents’ quality of life, and quality experiences for tourists. In G. Jennings and N. P. Nickerson (Eds.), Quality tourism

experiences, pp. 115-135. Oxford: Elsevier.

Chancellor, C., Yu, C.-P. S., & Cole, S. T. (2011). Exploring quality of life perceptions in rural midwestern (USA) communities: an application of the core–periphery concept in a tourism

development context. International Journal of Tourism Research,

13(5), 496-507.

Choi, H. S., & Sirakaya, E. (2005). Measuring Residents’ Attitude toward Sustainable Tourism: Development of Sustainable Tourism Attitude Scale. Journal of Tourism Research, 43, 380-394.

Davidson, W. B., & Cotter, P. R. (1991). The relationship between sense of community and subjective well-being: A first look. Journal of

Community Psychology, 19, 246-253.

Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40,

189-216.

Dillman, D. (2000). Mail and internet services: The tailored design

method. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Dissart, J. C., & Deller, S. C. (2000). Quality of life in the planning literature. Journal of Planning Literature, 15(1), 135-161. Dogan, H. (1989). Forms of adjustment: Socio-cultural impacts of

tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 16, 216-236.

Methodology and Research Inferences. The Impact of Tourism.

Sixth Annual Conference Proceedings of the Travel and Tourism Research Association. San Diego.

Dyer, P., Gursoy, D., Sharma, B., & Carter, J. (2007). Structural Modeling of Resident Perceptions of Tourism and Associated Development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Tourism

Management, 28(2), 409-422.

Esman, M. (1984). Tourism as Ethnic Preservation: The Cajuns of Louisiana. Annals of Tourism Research, 11(4), 451-467. Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation

Models with Unobservable variables and Measurement Error.

Journal of Marketing Research, 18(February), 39-50.

Getz, D. (1994). Resident attitudes toward tourism: A longitudinal study in Spey Vally, Scotland. Tourism Management, 15(4), 247-268. Grayson, L., & Young, K. (1994). Quality of life in cities: An overview

and guide to the literature. London: The British Library.

Gursoy, D. J., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes: A structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79–105.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–53. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indices in

Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55.

Jurowski, C. (1994). The interplay of elements affecting host community resident attitudes toward tourism: A path analytic approach. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA.

Jurowski, C., & Gursoy, D. (2004). Distance effects on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 296–312.

Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural Equation

Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Hillsdale, NJ:

Ko, D. W., & Stewart, W. P. (2002). A Structural Equation Model of Residents Attitudes for Tourism Development. Tourism

Management, 23, 521-530.

Lankford, S., & Howard, D. (1994). Developing a tourism impact attitude scale. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(1), 121–139. Lee, C-K., & Back K. J. (2003). Pre- and post-casino impacts of

residents’ perceptions. Annual of Tourism Research, 30(4), 868-885.

Lindberg, K., & Johnson R. L. (1997). Modeling Resident Attitudes toward Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 24(2), 402–424. Liu, J. C., & Var, T. (1986). Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in

Hawaii. Annals of Tourism Research, 13(2), 193–214.

Marcouiller, D.W. (1997). Towards integrative tourism planning in rural America. Journal of Planning Literature, 11, 33-357.

Marsh, H. W., Balla, J. R. & McDonald, R. P. (1988). Goodness-of-Fit Indexes in Confirmatory Factor Analysis: The Effect of Sample Size. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 391–410.

McCool, S. F., & Martin, S. R. (1994). Community attachment and attitudes toward tourism development. Journal of Travel

Research, 32(3), 29-34.

McCool, S. F., & Moisey, N. (1996). Monitoring resident attitudes toward tourism. Tourism analysis, 1, 29-37.

Morrison Institute for Public Policy (1997). What Matters in Greater

Phoenix: 1997 Indicators of Our Quality of Life. Tempe:

Arizona State University.

Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling

Procedures: Issues and Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications, Inc.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory. (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I H. (1994). Psychometric Theory. (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Orange County Economic Development Partnership (2009). Workforce

and Training. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Allen, L. R. (1990). Resident support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(4), 586–599.

Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Kang, Y. S. (1999). Boomtown tourism and resident quality of life: The marketing of gaming to host community residents. Journal of Business Research, 44, 165-177.

Roehl, W. S. (1999). Quality of Life Issues in a Casino Destination.

Journal of Business Research, 44, 223-229.

Rosenow, J. E., & Pulsipher, G. L. (1979). Tourism: The Good, the bad

and the ugly. Kansas City, MO: Media Publishing.

Ryan, C. (1991). Recreational Tourism: A Social Science Perspective. London: Routledge.

Sirakaya, E., Ekinci, Y., & Kaya, K. G. (2008). An Examination of the Validity of SUS-TAS in Cross-Cultures. Journal of Travel

Research, 46(4), 414-421.

STATS Indiana. (2009). STATS Indiana Profile. Retrieved March 10, 2009, from

http://www.stats.indiana.edu/profiles/custom_profile_frame.html Vargas-Sánchez, A., Plaza-Mejía, M. A., & Porras-Bueno, N. (2009).

Understanding Residents’ Attitudes toward the Development of Industrial Tourism in a Former Mining Community. Journal of

Travel Research, 47, 373-387.

Wilkin, J. (2006). Tourism development in Butte-Silver Bow: Visitor

profiles and resident attitudes. University of Montana Institute

for Tourism and Recreation Research Report 2006-2. Retrieved January 4, 2009, from

http://www.itrr.umt.edu/research06/ButteCTAP06.pdf

Yu, C.-P., Chancellor, H. C., & Cole, S. T. (2009). Measuring residents' attitudes toward sustainable tourism: A reexamination of the sustainable tourism attitude scale. Journal of Travel Research, 0047287509353189.

Received April 22, 2011 Revised August 12, 2011 Accepted August 18, 2011