行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

社區與環境治理─台灣地方永續發展的制度性能建構與政

策網絡化(2/2)

研究成果報告(完整版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 95-2414-H-004-069- 執 行 期 間 : 95 年 08 月 01 日至 97 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學政治學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 湯京平 報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢中 華 民 國 97 年 10 月 30 日

社區與環境治理─台灣地方永續發展的制度性能建構與政策網絡化 目錄 摘要 2 壹、前言 3 貳、研究目的 8 參、理論架構與相關文獻 8 肆、研究方法 10 伍、結果與討論 11 陸、參考文獻 15 柒、計畫成果自評 20 附錄一 22 附錄二 58

摘要 鑑於各國政府在保育工作上的成效不彰,以社區為單位鼓勵民間自主的環境保 護、資源管理以及生態保育工作,近年在聯合國所屬的國際組織大力推動下,已成 國際趨勢。我國民主化之後,社會力漸強,加上新公共管理運動的風潮,也開始重 視社區在治理上的角色。然而,社區到底能在我國追求永續發展的治理體系中,究 竟發揮何種功能,卻一直缺乏有系統的研究。本計畫針對國內都市、鄉村以及原住 民部落(棲蘭森林區旁的新光、鎮西堡與司馬庫斯以及蘭嶼達悟族人的部落等)等 不同社區,作為研究的對象,有系統地探討社區在共享性資源維護的可能貢獻。本 研究假設,當社區能夠發展出一種與外在社會利益結合的共生結構,就容易進一步 從資源的取用者身份,轉化成資源的有效管理者。而生態旅遊的推廣,就有助於塑 造這種互利的結構。本研究將透過深度訪談等質化研究的方式,輔以地理資訊系統 的協助,整理這些社區成功或失敗的經驗,並將其轉化成有系統的知識,俾能改善 我國地方永續發展的制度性能,並協助決策者建構有效的政策網絡。

壹、 前言 由下而上的社區在治理功能,不論在學界還是在實務界,所受到的重視可謂與 日俱增,且為跨學科領域及全球性的。不管是已開發國家還是開發中國家,都能看 到以社區為治理主軸的實驗性措施與制度的發展,在環保、社會福利、治安及教育 等政策議題上被積極推動,其成效被仔細檢驗,潛力與挑戰被熱烈討論。在台灣, 社區也是近年民主化與新公共管理兩大改革趨勢以及環境保護運動演變的輻奏點。 台灣公共行政學的發展,長久以來一直比較受到管理學的影響,也許是因為過去經 歷長期威權統治之故,研究重點比較強調行政效率及政策合理性的追求。隨著近二 十年來的民主轉型與鞏固,治理工作研究開始強調如何走出「發展國」(developmental state)的框架,讓行政效率與較廣泛的政治制度(如選舉、分權制衡等)及民主規範 (代表性、課責性、程序正義、分配正義及公民參與等)結合及妥協。讓社區積極 參與政策的制訂與執行不但是民主化過程中已經發生的事實,也是值得鼓勵的趨 勢。此外,盛行於英、美、澳、紐等國家的新管理主義或新公共管理運動,也在國 內被大力推動與實踐。這個築基於志願合作與網絡建構的新治理模式,不但重視跨 部門(政府、營利部門、以及第三部門)間的協力增效,也強調治者與被治者間合 產(co-production)機制的發展,以及上下級政府機構間的伙伴關係(partnership) 的建構,而使社區在治理任務上的潛能被發掘出來。這兩項政治與行政的發展,在 「社區治理」的概念上聚焦,再加上近年的環境運動與管理,也演進到第三世代強 調由下而上草根參與的「社基管理」(community-based management),同樣把社區放 在聚光燈之下,成為備受重視的治理單位。 (1)民主化與社區 民主化的治理強調政策的回應性(responsiveness)、透過公民參與(civic participation)所強化的正當性(legitimacy)、以及透過賦權(empowerment)而得以 確保的課責性(accountability)。台灣民主化過程中首先為政府治理工作帶來的衝擊 就是此起彼落的社會運動與自力救濟的抗爭。雖然學者一般將 1987 年解除戒嚴視為 台灣民主轉型的分水嶺,但早在 1980 年代初期,台灣的威權政體就採取了一連串的 自由化的措施,對於此起彼落的消費者、環保、農民、榮民、學生等運動,採取比

較寬容的態度,並嘗試在政策上回應這些來自社會的訴求。雖然許多運動與抗爭發 生在首都,以中央政府為訴求對象,更有非常多的草根性抗爭團體,以社區為主體, 動員起來表達對於特定現象(如污染)及對象(廠商或政府)的不滿,為各級政府 的施政帶來非常大的壓力。經過多年民主化過程中的制度建構(如公害糾紛處理法、 空污法中的公民訴訟機制),已讓行政單位更重視來自基層的呼籲;也讓來自社區的 草根性社會力量更有機會得到政府在政策上的回應。 與前述社會抗爭相關的發展是民主化之後對政策正當性的需求更甚,因此政府 往往必須透過公民參與及政策過程中的程序正義來強化政策的正當性。在威權體制 之下,政府施政的正當性主要來自法律的授權,對抗或違反法律的行動都受到譴責。 但民主化之後,尤其在大眾傳播媒介發展成熟後,既有法律的正當性可能透過媒體 悲慘故事的報導以及強烈抗爭民意的呈現,而受到質疑。因此,如何透過合理的參 與管道,將抗爭行動內化至政策制訂的過程中,試圖化解衝突,或至少提供反對者 充分表達的機會,才比較能避免保政策執行時遭遇來自被治者的頑強抵抗。「社區」 或村里之為基層組織,在動員各類政策倡議行動(advocacy action)、強化溝通與化 解衝突,乃至於塑造共識等方面,實據有非常重要的樞紐地位。 公民參與的另一個面向則是賦權:參與的目的是要影響政策的制訂與執行,如 果政策制訂者不把權力適當地釋放給參與者,則參與並沒有意義。許多參與機制並 沒有約束力,往往無法引起廣泛參與的興趣。有些機制(如環境影響評估中的公聽 會)則有較大的影響力。在制度中嵌入公民較有影響力的參與機制即為民主規範性 原則中的「權力附屬原則」(Principle of Subsidiarity, Shuman, 1998):決策的權力應 被等比例地下放給受決策影響最大的人,讓他們在某些程度上能夠有選擇自己偏 好、決定自己命運的權利。這原則除了是一種規範性訴求,也往往是影響政策效果 的重要因素:當決策權越接近被治者,其越有動機與能力把在地知識融入決策內容 中,並找到結合個人利益與集體利益的可能,設計出適當的誘因機制,不但讓政策 的可行性更高,決策的內容也更容易滿足更多被治者的需要,讓政策達到更高的總 效益。由於社區常常是許多政策的標的與執行單位,把決策權下放給社區民眾在近 年也是十分普遍的作法。 (2)新公共管理與社區

新公共管理的風潮也把社區視為非常重要的治理單元。新公共管理在原來的管 理主義中加入經濟學的原則,企圖為特定的公共財貨的生產、公共服務之提供,或 自然資源耗竭的悲劇,設計出最適當的治理結構。從古典經濟學的觀點,在市場可 以處理的情境下,應有市場來處理;當市場發生失靈的情形,則國家獲得介入的正 當性。而制度經濟學或新制度主義則主張,雖然層級結構(契約)或國家力量權威 性的介入有時能夠降低不確定性,矯正市場失靈的情形,但這些矯正市場失靈的制 度卻可能因為資訊不對稱及成員的機會主義等問題,導致國家或權威體制的失靈。 因此,如何建構更精緻的治理網絡,納入多元的誘因結構─不僅僅依賴政府的強制 力,更依賴志願性的交易關係,來矯正市場與國家的失靈。 緣此,網絡治理的概念因而受到重視。在特定的政策網絡中,參與治理者各有 不同的參與動機,公部門的行動基礎可能集體(公共)利益或政治人物的選擇性誘 因(selective incentives);私部門的參與往往是因為有利可圖,追求誘人的物質性誘 因(materialistic incentives);而第三部門則可能為慈善性(philanthropic) 或理想性 誘因(purposive incentives)參與治理的集體行動。而社區則是上述各類的綜合體: 一方面社區成員可能有某種共同利益值得成員以集體行動來追求,另一方面社區成 員也可能分享共同的願景及理想而投入治理的行動;當然也無法避免個別成員可能 有隱藏的自利動機,希望在治理行動中伺機謀求自身利益的極大化。而社區治理最 特別的地方則是其治理者與被治理者的身份常常重合,而其特有的社群性誘因 (solidary incentives)往往可以讓這樣的自治工作能夠奏效:社區之為常碰面、互動 頻率甚高的初級團體,可能有因為親戚關係、風俗習慣、共同信仰等因素而有更深 厚的社會連結,透過互惠、信賴等特有的社會關係,對其成員產生更大的制約,資 訊能夠更有效地傳遞,因而在治理工作上有獨特的優勢,故導致近年公共行政學界 與實務界對社區的重視。 (3)新環境治理趨勢下的社區 近年環境保護學界與實務界更毫不保留地強調社區在治理的核心地位。盱衡全 世界環境保護政策的發展,可略分為三個階段:首先是 1970 至 1990 年代以國家強 制力介入為特色的規範性政策階段,此一階段興起了許多意識型態色彩濃厚的新社 會運動(如環保運動、消費者運動、女性運動等),而也克服了產業界的反對而制訂

了較嚴格的環境污染法規,嘗試處理市場失靈的所產生的外部效果。到了 1980 年代, 各國回顧環境管理的成效與問題,開始反省政府失靈的問題的現象,並進而思考如 何把市場的誘因機制引進環保法規之中,讓廠商自願投入污染減量的努力。到了 1990 年代,污染管制已有了初步的成效,棕色議題(Brown Agenda)獲得有效處理,許 多先進國家開始把焦點放在綠色議題(Green Agenda)之上,轉而注意生物多樣性的 維護、保育、資源永續利用等更複雜的問題。面對這些問題,強而有力的行政手腕 似乎缺乏明顯的著力點。反之,要處理這類綜觀的(holistic)、集體的、富有科技專 業意涵的治理任務,細緻的、充分結合行動者利益與意圖的網絡治理遂成主流 (Burgess, Clark, and Harrison, 2000; Chatterton and Style, 2001)。社區,在此被界定為 一個特定空間小型社會單位,具備同質性甚高的社會結構,成員間存在共同的利益 以及被共同認可的規範(Agrawal and Gibson, 2001),遂日益受到重視。這可以從美 國 1994 所成立的新單位─永續生態體系與社區辦公室(Office of Sustainable

Ecosystems and Communities)─以提供社區相關的訓練及行政支援,並積極倡議社 基環保行動方案(Community-Based Environmental Protection initiative)可窺一斑 (Colvin, 2002)。 以社區為基礎的環保或保育行動有理論上的優勢。其為治理者與被治者的介 面,且於其間治理者與被治者身份往往重合,降低使用者與管理者間資訊不對稱以 及利益衝突的情形,且其最接近治理的標的物(生態體系),治理標的物的永續利用 往往與其成員的利益有密切關連,因此比較容易建立起特有的誘因結構以進行有效 的管理。因此,當保育或生態維護成為環保的新焦點,社區在這方面的獨特地位遂 成為各方所重視的治理單元。因此 1990 年代後的環境政策新紀元堪稱是以建構「永 續社區」(Sustainable Community)為主軸(Mazmanian and Kraft, 1999)的草根性參 與治理(Mason, 2000;Weber, 2000)。

這類強調以草根行動來處理生態問題的新思維,可以「二十一世紀地方議程」 (Local Agenda 21, Lafferty and Eckerberg, 1998)的國際串連為代表。這個環境治理 新典範強調全球環境問題的在地行動,認為有效的環境治理必須透過開放而具有彈 性的架構進行決策,以讓多元利益能被納入考量,並主張利益涉入者間的對話與資 訊分享,並跨部門的聯合行動來執行環境治理的具體方案(Barrett and Usui, 2002:

經濟活動、乃至於制度與權力結構等)和自然生態的互動關係。而社區則是瞭解這

種人文與自然互動關係的最適情境(Bridger and Luloff, 1999)。這種強調「人在自然

中」(humans-in-nature)的觀點迥異於以往「以人為中心的」(anthropocentric)生態 觀,認為社會和自然體系有密切的連結,恣意切割將導致政策偏差,以致妨礙自然 資源的有效管理及生態的永續維護(Berkes and Folke, 1998)。

順著這種以特定地區為認知基礎(place-based)、強調人類與自然關係的理解架 構觀察,則不難理解近年關於生態保育及自然資源維護的研究,不約而同地聚焦於 社區及其住民和保育成效的關連。此間一個頗受重視的研究主題是原住民對於其所 依賴的特定自然資源(常常是共享性資源)的維護。因為這些原住民在其生態體系 中已以可持續性的方式生活數世代,因此必然已經發展出某些在地的智慧及有效的 制度以與自然和諧共處。一方面這些智慧與制度不乏值得外地人效法之處,因此值 得深入介紹;另一方面在資本主義及全球化的衝擊下,這些原住民社區不再能與世 隔絕,其與自然和諧的關係也因為外地人的移入、被整合進更大的社會結構中、經 濟型態的轉變、以及新價值觀的植入等因素,而產生劇烈的變動(Freitas, Kahn, and

Rivas, 2004)。從這個觀點出發,這些原住民社區的人和制度如何面對這些挑戰,迅

速適應席捲而來的外在變化,似為更值得深入探索的重要課題(Kelly and Steed, 2004)。

此外,社區在環境保護受到重視的另一個原因是環境正義議題的興起。近年累 積的研究多證實,少數族裔以及貧窮的社區,在數十年來決策單位遵循「最少阻力」 的選址原則下,承受過多的污染性設施,擔負過大的環境風險,甚至導致嚴重的健 康危害。與此同時,隨著環境權概念的普及,抗議這類環境負荷分配不公的抗爭活 動也風起雲湧,形成學界所謂的「後院環境運動」(Backyard Environmentalism, Sabel,

Fung and Karkkainen, 2000)。這類以環境正義為主軸的新興社會運動,結合以拒絕環

境公害威脅為主要訴求的「鄰避症候群」(Not-in-My-Backyard, NIMBY Syndrome), 成為普遍存在於各國,手段最激烈、也最難以化解的環境抗爭。而這些抗爭集結都 是以社區為主要動員單位,顯示社區在此間所居之關鍵性地位。而社區掌握豐富的 在地知識與資訊,也獨具提出建設性衝突解決方案的能力,在化解對立、提升環境 正義等目標的追求,扮演著無可取代的角色。

貳、 研究目的

本研究的目的在於探究社區在台灣的環境治理體系中的地位,並透過案例分 析,瞭解目前運作層面的挑戰,進而為制度性能之建構(institutional capacity building)

與政策網絡化(policy networking),提供實務上的興革建議。就理論而言,民主化與 新管理主義的行政改革應會讓社區在公共事務的治理上扮演更活躍的角色。而就實 際操作面而言,我國的社區政策在各政府單位的蓄意推動(如環保署有環保社區表 揚、文建會的社區總體營造、農委會的富麗農/漁村、原住民委員會健康社區、觀光 局的『美麗台灣』社區競賽等)、私人企業的贊助(如福特汽車的保育及環保獎), 以及無數志願性團體的努力(如荒野協會、藍色東港溪協會等),已讓台灣許多社區 在環保成就上有令人驚豔的表現。然而,如何將這些成功的經驗轉化成能夠通盤適 用的制度,則需要有系統地蒐集資料,分析其成功的因素,並透過理論的詮釋,讓 這些精彩的故事變成可以傳承的知識。以往雖不乏有心人士把社區發展成功的案例 編輯成精美的專輯,成為可貴的紀錄,但在結合理論與案例以有效累積學界對社區 與環境治理關係的認識上,則略顯不足。為彌補此一缺憾,本研究挑選若干案例, 討論其理論意涵,並嘗試以較嚴密的實證研究方法,討論其成功發展的結構性與輳 合性因素,永續發展的挑戰與侷限,以及環境治理上的意義,希望能夠達到拋磚引 玉的效果,吸引學界先進在這方面投入更多心力,累積更多有系統且富於理論意涵 的案例研究。 參、 理論架構與相關文獻 從國際迅速累積的文獻中可以發展出一個簡單的命題:「要讓社區在環境治理中 發揮功能,除了必須尊重社區的自主權,更重要的是要發展出一種社區與外在社會 的利益共生結構,讓社區能在成功的環境治理中滿足自我發展的需求。」在能獲得 重大社區集體利益的前提下,社區領導者比較能夠塑造吸引眾人追隨的願景,克服

集體行動的邏輯下的搭便車效應,進而透過該集體行動在環境治理中扮演重要的角 色─例如,與更大的社會形成某種信託關係,接受社會的委託,代其管理自然資源 或防範污染的發生。這種共生的利益結構可能是自然形成的,但更可能是人為的, 由具有透過企業家精神的領導者創造或發現的。而近年發展此一利益共生結構最成 功的策略則是生態旅遊(ecotourism, Campbell, 1999; Belsky, 1999)的提倡。

一般而言,越是基層的治理單位,越容易受到地方經濟發展的壓力,畢竟經濟 條件直接影響個人及其家人的生存機會,是人性中最基本的需求。而社區之為最基 層的治理單位,當然也受到這個法則的約束,因此要期待社區在環境治理上扮演重 要角色,則必須在某種程度上先滿足其經濟發展的要求,讓環境問題與經濟問題能 夠一併解決,此乃「永續(地方)發展」訴求吸引人之處。生態旅遊既然強調要讓 生態資源成為吸引遊客的重點,因此對於這些資源就絕對有妥善保護的動機,且成 功的旅遊事業不但可能挹注外來資源,解決地方貧窮落後的問題,也可能提升居民 的榮譽感與自尊(Milne and Ateljevic, 2001)。而在原住民社區,對於保存特有文化

傳統、生活模式、乃至於信仰價值等有特殊需求者,則可加上「異族觀光」(Ethnic Tourism, Oakes, 1993)元素,讓保存自然生態、傳承文化特色、以及改善經濟狀況三 種目標同時達成。 若把分析層次從社區降到個人,則要討論的主題變成影響個人參與社區營造集 體行動的因素為何。這雖然是個老生常談的問題,但對於社造的實踐者而言卻一直 是非常核心的問題,仍需要累積更多更具學術理論依據的論述。根據 Wilson (1976) 的 分類,個人參與集體行動的誘因大致可分為物質性誘因(materialistic incentives)、理

想性誘因(purposive incentive)、以及社群性誘因(solidary incentive)三種。物質性 誘因乃指成員期待參與行動能夠獲得實質的利益,這可以從預期獲得的收入、補助 等來估計。理想性誘因乃指成員期待參與行動能夠獲得意識型態上的滿足,這部分 通常是比較冠冕堂皇的論述,或領導者提供的願景。社群性誘因乃指源於社會或人 際關係的動機,成員參與時會期待所屬團體成員的肯定與讚賞(或反之,不合作則 擔心受到懲罰)。緣此,一組簡單的命題可以被提出來檢證:當上述各項誘因強度增 高時,社區營造集體行動的成功機率就會增加。然而,這些誘因對於參與者行動所

產生的推力,可能不是簡單的累積效果。誘因之間,可能有某些競爭或合作的關係。 這些複雜的關係,卻一直缺乏更細緻的分析,值得深入探討。 肆、 研究方法 一、本計畫採用之研究方法與原因 本研究將以比較個案研究法進行。此處個案研究將採取接近人類學者常用之人種 誌長期觀察法:除了朴子溪畔的社區外,不論是司馬庫斯的泰雅族或蘭嶼的達悟族 部落,都有非常獨特的文化傳統,其對於社區、生態、保育、觀光乃至於社會關係 等字彙,可能會有不同的認知或詮釋,精簡的深入訪談可能因文化差異而錯誤詮釋 受訪者的意見。因此在作法上,除了平常蒐集這些族裔的文化資料外,也將在假期 中透過較長時間滯留當地的方式,觀察社區成員互動的模式,學習其語言、參與其 日常勞動及祭祀等活動,以期深入到其文化較基層的思維結構中,精準理解並他們 眼中的世界與社會關係。當然,為能蒐集到有系統的資料,深入訪談也是必要的方 法。而訪談的對象,則希望透過滾雪球的方式累積,訪談的方式也將以較隨性的方 式進行,透過長期信任感的培養,引導受訪者提供具體而深入的資訊。訪談資料的 整理將重視受訪者說法的交叉比對,以評估資料的可信度,並呈現社區成員間的共 識與歧見。 二、預計可能遭遇之困難及解決途徑 因為本研究將針對少數個案進行比較,故無可否認的,它將在因果推論的強度上 有重要的限制。因為所觀察的對象(observations)太少,故此類以少數個案分析 (few-case studies)為主要設計的研究,應避免定位成因果理論的檢證性研究─畢竟 在技術面它很難否定其他可能同時存在的因果關係(社會現象很少因單一因素而形 成),也很難證明所提出的解釋因素對該個案有最關鍵性(deterministic)的影響,因

此這類研究活動所面對的「因果推論的基本問題」(Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference)將更加難以克服。這是所有質化研究中,少數或單一案例研究所面臨的方 法論上的共同問題(King, Keohan, and Verba, 1994)。

然而,同樣無可否認的,乃是此類質化研究能夠以細膩的文字敘述,以整體的觀 點刻畫變數間的複雜而細緻的互動,闡明變數間包含因果及以外的各類關係。相對 於量化研究強調過程的嚴謹卻失之機械化,質化研究比較有富於彈性並能避免研究 流於虛無主義(Nihilism)的批評(Bernstein, 1976)。 為克服本研究先天體質上的困難,研究者一方面必須在論證方式上稍做調整:避 免以嚴格的因果關係進行論述,而應強調本研究啟發性的價值,旨在「發現」可能 成功的因素,而非「證明」或「否證」特定理論或模型的有效性。另一方面,為增 強因果論證的強度,本研究亦致力於增加所觀察的案例及案例間變因的控制,俾能 減少在論證時因為變數多於案例所造成的推論不足的相關問題。這樣的研究,若能 吸引學界同儕援用並做類似案例的進一步比較分析,其將亦能有非常具體學術貢獻。 另一個技術性的困難,源於本研究擬採深度訪談來獲得實證性資料。這類訪談所 面臨最大的問題,是實證資料的可信度。實證分析依賴深度訪談,但許多受訪者會 因為私人因素(private agenda)而對事實真相有所保留,甚至刻意加以扭曲。尤其本 研究的題材可能涉及特別高度敏感的議題─如核四公投等高度爭議性的問題,故此 類疑慮可能特別明顯。訪問者事前縝密的資料搜集與分析,將有助於察覺有疑問的 訪問內容。對於有疑問的受訪內容亦可透過不同受訪者間的交叉詢問來加以釐清, 以獲得較接近真相的說法。因此類面訪技巧對經驗不足的助理而言,可能非一蹴可 幾,故在初期計畫主持人應儘量親自進行訪問,以給予助理更多見習、實習的機會。 伍、 結果與討論 本研究的目的在探討一個簡單卻十分重要的命題:「要讓社區在環境治理中發揮 功能,除了必須尊重社區的自主權,更重要的是要發展出一種社區與外在社會的利 益共生結構,讓社區能在成功的環境治理中滿足自我發展的需求。」在發展這類「利 益共生結構」的過程中,不但有外生(exogenous)制度的採用與引進,也有內生的 正式與非正式制度的演化與發展。社區要能發揮保育的功能,往往必須在內、外生 制度及正式、非正式制度間,達到某種均衡,以維持該制度群(institutional

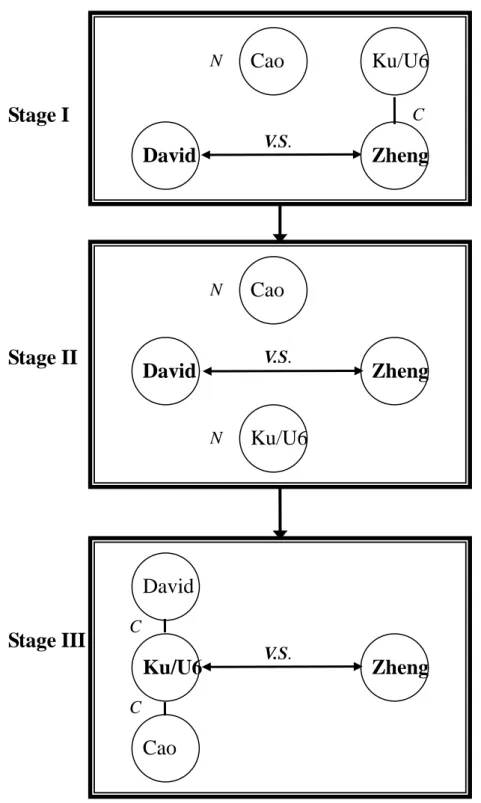

Constellation)的穩定運作。 因此,本研究的第一階段,是針對兩個原住民群體─泰雅族的司馬庫斯(新竹 縣尖石鄉)與達悟族的蘭嶼(台東縣蘭嶼鄉),進行宏觀的比較研究,希望探討非正 式的社會組織(宗教)在經歷重要轉變(從傳統宗教改宗為天主教或基督教)之後, 是否會影響該群體的保育表現。更確切地說,原住民社會的制度群在某些部分遭受 衝擊而開始改變,是否將引發一連串相關的變化,最後導致保育成果的變化,是本 研究第一階段希望探討的主題。結果顯示,原住民社會的傳統可能在前一個均衡達 成後,即在維護生態平衡,保護在地自然資源等方面,扮演重要角色。例如,達悟 人在過去三百年之中,以各種禁忌限制族人捕捉迴游性魚類(飛魚)的數量,有效 地達到飛魚永續利用的成果。這種現狀在基督教傳入、蘭嶼傳統社會對外開放,以 及現代科技引進之後,產生急遽的變化,如禁忌傳統的破壞搭配機動船的引進後, 近年飛魚的魚穫量業已銳減,顯示生態平衡已遭破壞,顯示當初的制度均衡不復存 在,導致治理功能的喪失。 但泰雅族司馬庫斯的發展,則展現新制度均衡點的達成。泰雅族人因為新經濟 模式及山地保護政策導致發展相對落後的不幸後果,近年則亟思以生態旅遊 (ecotourism)及異族觀光(ethno-tourism)等發展模式,積極改善原住民的經濟低 度發展現況。然而,資本主義市場經濟的引入,卻導致導致社區內人際關係的緊張 以及生態環境的浩劫。在教會的帶領下,司馬庫斯的居民利用集體意識的傳統,發 展出「共同經營」的獨特運作模式,成功地化解部落內的競爭,避免觀光活動造成 生態破壞,似乎形成了一種新的制度均衡。 上述研究發現顯示社區可以成為環境治理的主角,不但是政策執行單位,也是 地方永續發展政策的創意來源。而是否能夠透過集體行動所促成的制度的變革與新 制度均衡點的達成,則是制度性能(institutional capacity)良窳的重要關鍵。 本研究的第二階段則是針對城市型與鄉村型的社區保育行動進行分析。鄉村型 的保育行動,恰如原住民社區的保育努力,必須與經濟發展的因素掛勾。由於保育

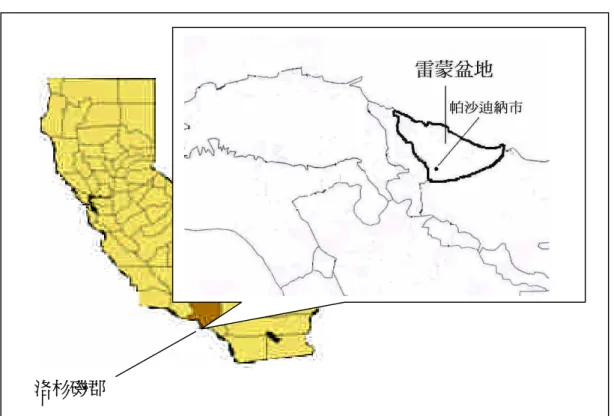

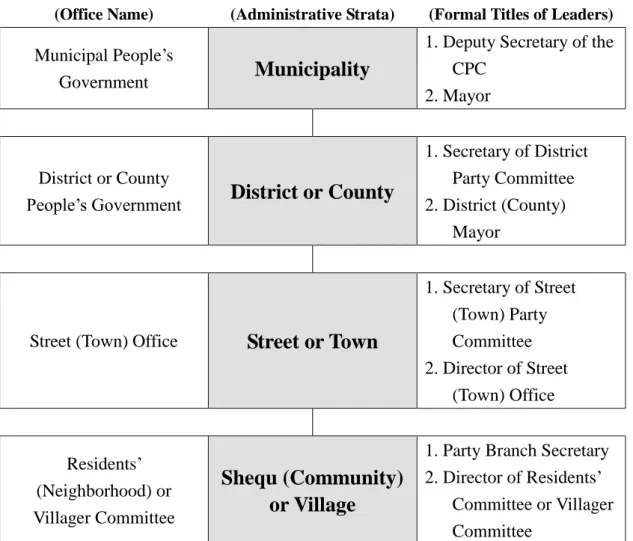

解決生計問題,否則侈言保育多為不切實際的想法。在嘉南地區的地下水資源保育 的案例中,呈現這類共享資源悲劇的特性:當保育的標的與在地的主要生產方式息 息相關,同時取用者的社區疆界非常不明確時,保育的工作非常不容易透過草根的 力量來執行。而必須藉由層級較高的政府單位,作跨部會整合的努力,透過多元治 理方案的推動,始能提供有效的誘因,讓資源使用者配合減少資源的取用量。然而, 這類政府介入的政策,並不一限於管制性的手段。對照之下,美國南加州的地下水 保存方案,則是透過法院,進行對於地下水區(乃至於使用者社群)範圍的釐清, 以及水權的重新界定,以即與之相關的市場機制,來提供使用者的誘因,管制水資 源迅速浩劫的趨勢。 另外一個案例是關於山坡地保育的研究。一個遍植檳榔山地社區在地震之後面 臨土石流威脅,在抗拒遷村的背景下,形成草根性的社區自然保育運動,村民砍除 淺根性的檳榔樹,改植具水土保持功能的林木,並企圖透過生態旅遊的經營,作為 主要營生的方式,改善當地經濟狀況。雖然這個社區享有相當高的知名度,也享有 來自政府與社會各界龐大的捐助,但最後並沒有形成一個能夠永續經營的運作型 態。保育的集體行動,原本是以理想性誘因來募集眾人的支持,許多人出錢出力, 為生態村的理想犧牲奉獻。當外界大量資源開始挹注,整個保育的努力就滲入了資 源分配的元素。既是分配,就有競爭關係,原來同舟共濟追求共同目標的正和賽局 (positive-sum game),就轉變成競相分食外來資源大餅的零和賽局(zero-sum game)。此時,一方面領導者的威信與公正性容易受到挑戰,一旦參與者覺得分配不 公或是期待落空,就容易懈怠甚至退出集體行動;二方面原先公益取向的行動誘因, 在外來資源的挹注補償之下,將受到嚴重侵蝕。習慣於獲得物質報償的行動者在失 去物質報償之後,將不再能夠重新以公益性的誘因加以動員,是謂誘因的排擠效果。 此時,保育的集體行動就面臨瓦解。此一案例提供了非常重要的政策意涵,亦即, 外界的資源挹注可能有揠苗助長的反效果。對於社區草根保育努力的政策性支持, 應該著重於培植其永續經營發展的制度與能力,在投入財務方面的協助之前,必須 先確定社區中資源公平分配的機制已然確立,否則外在資源一旦撤離,也將宣告社

區集體行動的終止。 第四個案例是都會型的草根保育行動。這類保育努力與鄉村型的保育對照之 下,特色在於理想性格相對濃厚。都會社區的成員,多半有其他穩定的職業,不必 依賴保育標的作為主要生計來源。此間固然也有物質相關的誘因,如都會中寸土寸 金的空間利用可能也是決策的主要考量。但只要能夠與生計脫勾,就能夠有更寬廣 的想像空間與創意的揮灑。緣此,都會的社區保育,往往是一種教育與協商的過程: 保育的概念被引進後,若能獲得專業的協助,並透過某些基層人際網絡推廣保育的 觀念,就很可能有令人驚豔的成就。此時,社區保育的集體行動比較依賴社群性誘 因和理想性誘因的主導。理想性誘因可能從環保團體引進;社群性誘因,則靠地方 菁英的經營。環保團體與草根菁英的結合當然非一蹴可幾,也有很多磨合上的困難, 但從台北的富陽公園以及台南的巴克禮公園等案例來分析,兩者的關係雖然不算一 拍即合,利益互補,但要找到合作的空間,也不算是緣木求魚。 除此之外,本研究還支柱許多研究生進行各類社區保育行動的研究。除了農村 型的社區,也有漁村型的保育,如台北縣北海岸的卯澳社區;此外也研究社區保育 運動的結盟,如林邊溪沿岸的幾個不同族裔(福佬、客家、原住民)社區之間的協 同發展。另有社區和環保團體對抗,反對保育運動的有趣題材,如高雄洲仔濕地的 保育抗爭等。而社區保育不能不論及在地的政治結構,故也有研究生以地方派系為 主軸,探討農村社區發展的政治面因素。這些都寬廣的主題,企圖描繪社區保育的 豐富面貌以及福雜的影響因素,有朝一日將被整理成比較完整的論述。

陸、 參考文獻 成露茜、夏鑄九、陳幸均、戴伯芬,2002,〈朝向市民城市:台北大理街社區運動〉, 《台灣社會研究季刊》,46:141-172。 朱念謙、侯錦雄,1998,〈台中市黎明住宅社區居民社區意識之研究〉,《建築學報》, 24:51-65。 李永展,2000,〈第五章 社區、永續性及城鄉發展〉,《永續發展:大地反撲的省思》。 台北:巨流,頁 99-123。 洪廣冀,2000,〈森林經營之部落、社會與國家的互動:以新竹司馬庫斯部落為個案〉, 台北:台灣大學森林學研究所碩士論文。 孫銘燐,2002,〈誰的馬告檜木國家公園-從抗爭符碼運用到在地參與認同?〉,新 竹:清華大學社會學研究所碩士論文。 陳玉美,1999,〈蘭嶼雅美族的社會與文化〉,台東:「1999 台東南島文化節」學術演 講。 陳欽春,〈社區主義在當代治理模式中的定位與展望〉,《中國行政評論》,46:141-172。 黃國超,2001,〈「神聖」的瓦解與重建-鎮西堡泰雅人的宗教變遷〉,新竹:清華大 學人類學研究所碩士論文。 黃瑞茂,2000,〈社區行動重構「生活地圖:台北福林社區社區參與公園改造經驗 (1993-1998)」〉,《都市與計畫》,27(1):81-96。 劉健哲,2001,〈德國農村社區更新及其對臺灣之意義〉,《農業經濟年刊》,2:1-29。 劉健哲,2002,〈村民參與農村社區更新之研究:德國經驗〉,《農業經濟年刊》,71: 157-193。 鄭漢文,2003,〈蘭嶼雅美大船文化的盤繞-大船文化的社會現象探究〉,花蓮:東 華大學族群關係與文化研究所碩士論文。 環保署,2001,《環保政策月刊》,4(10)。 鍾頤時,2003,〈探索原住民部落的環境教育-以馬告運動中的新光、鎮西堡部落為 例〉,台北:台灣師範大學環境教育研究所碩士論文。

Agrawal, Arun, and Clark C. Gibson. ed. 2001. Communities and the Environment:

Ethnicity, Gender, and the State in Community-Based Conservation. New Brunswick,

N.J.: Rutgers University Press.

Agyeman, Julian, Robert D. Bullard, and Bob Evans. 2002. “Exploring the Nexus: Bringing Together Sustainability, Environmental Justice and Equity.”Space and Polity 6(1): 77-90.

Arias-Maldonado, Manuel. 2000. “The Democratization of Sustainability: The Search for a Green Democratic Model.”Environmental Politics 9 (4): 43-58.

Baden, John A., and Douglas S. Noonan, ed. 1998. Managing the Commons. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Bardhan, Pranab, Luiz Carlos Bresser Pereira, László Bruszt, Jang Jip Choi, et al.

Sustainable Democracy. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Barndon, Katrina, Kent H. Redford, and Steven E. Sanderson. ed. 1998. Parks in Peril:

People, Politics, and Protected Areas. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Baron, Stephen, John Field, and Tom Schuller. ed. 2000. Social Capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barrett, Brendan, and Mikoto Usui. 2002. “Local Agenda 21 in Japan: Transforming Local Environmental Governance.”Local Environment 7(1): 49-67.

Belsky, Jill M. 1999. “Misrepresenting Communities: The Politics of Community-Based Rural Ecotourism in Gales Point Manatee, Belize.”Rural Sociology 64(4): 641-666. Berkes, Fikret, and Carl Folke, ed. 1998. Linking Social and Ecological Systems:

Management Practices and Social Mechanisms for Building Resilience. Cambridge,

New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bermeo, Nancy. ed. 1991. Liberalization and Democratization: Change in the Soviet

Union and Eastern Europe. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bernard, Ted, and Jora Young. 1997. The Ecology of Hope: Communities Collaborate for

Sustainability. Gabriella Island, B.C., Canada: New Society Publishers.

Bridger, J. C. and A. E. Luloff. 1999. “Toward an Interactional Approach to Sustainable Community Development.”Journal of Rural Studies 15: 376-387.

Burger, Joanna, and Justin Leonard. 2000. “Conflict Resolution in Coastal Waters: The Case of Personal Watercraft.”Marine Policy 24: 61-67.

Burgess, Jacquelin, Judy Clark, and Carolyn M. Harrison. 2000. “Knowledges in Action: An Actor Network Analysis of a Wetland Agri-enviroment Scheme.”Ecological

Economics 35: 119-132.

Campbell, Lisa M. 1999. “Ecotourism in Rural Developing Communities.”Annals of

Tourism Research 26(3): 534-553.

Carmin, Joann. 2003. “Non-Governmental Organisations and Public Participation in Local Environmental Decision-Making in the Czech Republic.”Local Environment 8(5): 541-552.

Cellarius, Barbara A., and Caedmon Staddon. 2002. “EnvironmentalNongovernmental Organizations, Civil Society, and Democratization in Bulgaria.”Eastern European

Politics and Societies: EEPS 16 (1): 182-222.

Charles, Sabel , Archon Fung, and Bradley Karkkainen. 2000. Beyond Backyard

Environmentalism: Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press.

Chatterton, Paul, and Sophie Style. 2001. “Putting Sustainable Development into Practice? The Role of Local Policy Partnership Networks.”Local Environment 6(4): 439-452. Colvin, Roddrick A. 2002. “Insights and Applications: Community-Based Environment

Natural Resources 15: 447-454.

Deth, Jan W. van, Marco Maraffi, Ken Newton, and Paul F. Whiteley. ed. 1999. Social

Capital and European Democracy. London: Routledge.

Dunn, James R., John E. Kinney, Quorum Books. 1997. “Review of Conservative Environmentalism –Reassessing the Means, Redefining the Ends.”Energy 22(6): 631-633.

Freitas, Carlos E., James R. Kahn, and Alexandre A.F. Rivas. 2004. “Indigenous People and Sustainable Development in Amazonas.”World Ecol 11: 312-325.

Gary King, Robert O. Keohane, and Sidney Verba. 1994. Designing Social Inquiry:

Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University

Press.

Gibson, Clark C., Margaret A. Mckean, and Elinor Ostrom. 2000. People and Forests:

Communities, Institutions, and Governance. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Gittell, Ross, and Avis Vidal. 1998. Community Organizing: Building Social Capital as a

Development Strategy. Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage Publications.

Goble, Dale D., Susan M. George, Kathryn Mazaika, J. Michael Scott, and Jason Karl. 1999. “Local and National Protection of Endangered Species: an Assessment.”

Environmental Science and Policy 2: 43-59.

Haynes, Jeff. 1998. Democracy and Civil Society in the Third World: Politics and New

Political Movements. Malden, Mass.: Polity Press.

Hibbard, Michael, and Jeremy Madsen. 2003. “Environmental Resistance to Place-Based Collaboration in the U.S. West.”Society and Natural Resources 16: 703-718.

Hill, Ronald J. ed. 1999. The Experience of Democratization in Eastern Europe: Selected

Papers from Fifth World Congress of Central and East European Studies, Warsaw, 1995. London: Macmilian Press.

Innes, Robert, Stephen Polasky, and John Tschirhart. 1998. “Takings, Compensation and Endangered Species Protection on Private Lands.”Journal of Economic Perspectives 12(3): 35-52.

Jamison, Andrew, Ron Eyerman, Jacqueline Cramer, and Jeppe Laessoe. 1990. The

Making of the New Environmental Consciousness: A Comparative Study of the Environmental Movements in Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands. Edinburgh:

Edinburgh University Press.

Jänicke, Martin, and Helge Jörgens. 2000. “Strategic Environmental Planning and Uncertainty: A Cross-national Comparison of Green Plans in Industrialized Countries.”

Policy Studies Journal 28 (3): 612-32.

John, DeWitt. 1994. Civic Environmentalism: Alternatives to Regulation in States and

Communities. Washington D.C.: CQ Press.

Conceptual Model.”Journal of Community Psychology 32(20): 201-216.

Kidner, David, Gary Higgs, and Sean White. ed. 2003. Socio-Economic Applications of

Geographic Information Science. London: Taylor & Francis.

Kousis, Maria. 1999. “Sustaining Local Environmental Mobilizations: Groups, Actions and Claims in Southern Europe.”Environmental Politics 8 (1): 172-198.

Lafferty, W. M. and K. Eckerberg. 1998. From the Earth Summit to Local Agenda 21:

Working toward Sustainable Development. London: Earthscan.

Laurian, Lucie. 2004. “Public Participation in Environmental Decision Making.”Journal

of the American Planning Association 70(1): 53-65.

Mason, Michale. 2000. “Evaluating Participative Capacity-Building in Environmental Policy: Provincial Fish Protection and Parks Management in British Columbia, Canada.”Policy Studies 21(2): 77-98.

Mazmanian, Daniel A, and Michael E. Kraft. ed. 1999. Toward Sustainable Communities:

Transition and Transformations in Environmental Policy. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press.

Metrick, Andrew, and Martin L. Weitzman. 1996. “Patterns of Behavior in Endangered Species Preservation.”Land Economics 72(1): 1-16.

Milne, Jonathan. ed. 2001. Social Capital versus Social Theory: Political Economy and

Social Science at the turn of the Millennium. London: Routledge.

Musacchio, Laura R., and Robert N. Coulson. 2001. “Landscape Ecological Planning Process for Wetland, Waterfowl, and Farmland Conservation.”Landscape and Urban

Planning 56: 125-147.

Nakamura, Toshihiko. 2001. “Land-Use Planning and Distribution of Threatened Wildlife in a City of Japan.”Landscape and Urban Planning 53: 1-15.

Naughton-Treves, Lisa, and Steven Sanderson. 1995. “Property, Politics and Wildlife Conservation.”World Development 23(8): 1265-1275.

Oakes, T. S. 1993. “The Cultural Space of Modernity: Ethnic Tourism and Place Identity in China.”Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 11: 47-66.

Oldfield, Jon. 1999. “The Environmental Impact of Transition--A case study of Moscow city.”The Geographical Journal 165 (2): 222-231.

Ostrom, Vincent, Robert Bish, and Elinor Ostrom. 1988. Local Government in the United

States. San Francisco, California: ICS Press.

Parisi, Domenico, Michael Taquino, Steven Michael Grice, and Duane A. Gill. 2003. “Promoting Environmental Democracy Using GIS as a Means to Integrate Community into the EPA-BASINS Approach.”Society and Natural Resources 16: 205-219.

Polasky, Stephen, Holly Doremusm, and Bruce Rettig. 1997. “Endangered Species Conservation on Private Land.”Contemporary Economic Policy 15: 66-76.

Management: Comparative Analysis of Institutional Approaches in Australia and India.”Society and Natural Resources 14: 145-160.

Richard J. Bernstein. 1976. The Restructuring of Social and Political Theory. Penn: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Rose, Richard, and Doh Chull Shin. 2001. “Democratization backwards: the Problem of Third-Wave Democracies. ”British Journal of Political Science 31: 331-354.

Sexton, Ken, Alfred A. Marcus, K. William Easter, and Timothy D. Burkhardt. 1999.

Better Environmental Decisions: Strategies for Government, Businesses, and Communities. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Shuman, Michael H. 1998. Going Local: Creating Self-Reliant Communities in a Global

Age. NY: The Free Press.

Skonhoft, Anders. 1998. “Resource Utilization, Property Rights and Welfare –Wildlife and the Local People.”Ecological Economics 26: 67-80.

Songorwa, Alexander N. 1999. “Community-Based Wildlife Management (CMW) in Tanzania: Are the Communities Interested?”World Development 27(12): 2061-2079. Steins, Nathalie A., and Victoria M. Edwards. 1999. “Collective Action in Common-Pool

Resource Management: The Contribution of a Social Constructivist Perspective to Existing Theory.”Society and Natural Resources 12: 539-557.

Stevens, Stan. ed. 1997. Conservation Through Cultural Survival: Indigenous Peoples and

Protected Areas. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Taylor, Marilyn. 2003. Public Policy in the Community. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Vickerman, Sara. 1999. “A State Model for Implementing Stewardship Incentives to

Conserve Biodiversity and Endangered Species.”The Science of the Total Environment 240: 41-50.

Weber, E. 2000. “A New Vanguard for the Environment: Grass-roots Ecosystem Management as a New Environmental Movement.”Society and Natural Resources 13 (3): 237-259.

Western, David, R. Michael Wright, and Shirley C. Strum. 1994. Natural Connection:

Perspectives in Community-Based Conservation. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Wilson, James Q. 1995. Political Organizations , Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

柒、 計畫成果自評

本計畫的執行成果,就短期成就指標而言,不甚理想,但以長期的影響為評估 準則時,也可謂成果豐碩。本計畫以兩年的經費共計執行了三個年度,預計出版三 到四篇 SSCI 或 TSSCI 論文。其中,最早完成的英文論文,以「Religious Conversion and Indigenous Common-Pool Resource Governance: The Cases of Tao and Atayal in Taiwan」為題,討論原住民社區的保育工作,如何受到外在社會體系變遷的影響, 並檢視哪些因素讓這些原住民部落能夠順利適應社會轉型,成功地保護其周遭的自 然資源。因為期刊審查拖延之故,至今仍在審查過程中,手稿以及審查意見如附件 一。第二篇論文,以地下水的取用者自我管理為主題,檢視我國嘉南地區的地下水 超抽危機,並以南加州雷蒙集水區的成功自治為例,檢視在地資源自我管理的成功 因素為何。本篇論文於 2006 年底發表於政治學報,全文如附件二。第三篇論文討論 災後重建情境下的社區保育努力,以中部某個農村型的社區為例,探討由基層發起 的保育努力遇到政府介入後的策略回應以及產生的悲劇性效果。本篇論文剛完成, 正在某 TSSCI 期刊審查之中。第四篇論文則探討都市社區的保育努力,以台北的富 陽公園及台南的巴克禮公園為例,檢視基層社區在保護都會微生態的努力上,和專 業環保團體的共生與競爭關係。該論文正在撰寫之中,預計年底以前能夠完成,投 稿至期刊。 雖然在期刊出版的成果發表上,本研究遭遇到一些延遲,需要更多一點時間讓 論文刊出,但在整體上,本計畫卻透過指導研究生撰寫學位論文,累積了非常豐富 的實證資料,針對社區資源保育行動的各個面向,進行廣泛且深入的探討,足以作 為未來幾年學術出版的素材,詳如表一。這些研究半成品,將在近期內被加工整理 成冊,會是一本兼具理論論述與實證研究的完整學術著作,成為本研究計畫期刊出 版之外的輔助出版成果。

表一 計畫相關的碩士論文 李聯康,2008,都市中的保育行動─以富陽公園與巴克禮公園的社區參與為例(進 行中) 林易萱,2008,私有地上的生態保育─以雙連埤的集體行動為例(進行中) 黃詩涵,2007,社區總體營造的集體行動永續性: 橙花鄉明星社區的目標發展與政 府介入的政策角色 管珮鈺,2006,濕地保育與社基主義之困境:台灣濕地保護聯盟之洲仔濕地的保育 蘇霈蓉,2005,山地社區在自然資源管理的角色─以新竹縣尖石鄉司馬庫斯、鎮西 堡及新光部落為例 張詠羚,2005,非營利組織與社區發展─以台灣藍色東港溪保育協會倡導「林邊溪 右岸盟」為例 劉如倫,2005,台灣地方派系與社區營造─以嘉義縣東石鄉船仔頭和永屯社區為例 劉俊麟,2005,社區自治與漁村永續發展:以卯澳社區為例

附錄一 論文

Institutional Adaptation and Community-Based Conservation of Natural Resources:

The Cases of Tao and Atayal in Taiwan

Many aboriginal peoples have been identified to be successful in preserving scarce

local natural resources such as coastal fisheries, forests, and water systems by means of

self-governing arrangements that effectively limit the rate of resource extraction and use

(Kellert et al. 2000; Ostrom 2005). Some studies, however, contend that sustainable use

in some indigenous communities might not necessarily be the result of sound conservation

practices but merely a result of low demand relative to supply or poorly developed

resource distribution networks (Hunn, 1982; Alvard, 1995). Although both scenarios are

possible, a critical question is how indigenous communities may deal with increasing

pressures on their local resource systems, no matter whether the pressures have emerged

as a result of population and technological changes or economic and political changes,

from within or outside the community (cf. Ross 1978).

As part of the overall trends of modernization and globalization, for example, many

historically isolated indigenous communities have come into contact with the outside

world and begun to undergo social, economic, and cultural transformations; their

leading to an imbalance between supply and demand. As a result, local resources in

these indigenous communities could be ruined within a relatively short period of time, manifesting whatsomereferto asthe“realtragedy ofthecommons”(Anoliefo,

Isikhemhen, and Ochije 2003; Monbiot 1993).

One often-suggested solution is the involvement of indigenous communities as

partners in modern conservation efforts (Rangan and Lane 2001; Ross and Pickering

2002). This approach advocates the application of local knowledge and, in some cases,

the revival of indigenous cultural practices that have historically proven successful

(Colding and Folke 2001). Despite such an argument, the literature has devoted little

attention to explaining the circumstances in which indigenous institutions can help, and if

so how they can be adjusted, transformed, or rebuilt amidst rapid social changes such that

they remain effective in natural resource governance.

In this paper, we explore how such institutional adaptation processes are possible

by focusing on how traditional values and beliefs may contribute to nature conservation in

indigenous communities. As indigenous values and beliefs are replaced by those from

the outside, to what extent would traditional practices in nature conservation be affected?

Can outside influences be combined with indigenous practices to support effective

governing institutions for nature conservation? What are the potential challenges in these

evolution of two aboriginal communities in Taiwan.

In one case, the Tao people on Orchid Island had traditionally maintained communal

rituals that governed how boats were built, fish were caught, and seafood was cooked and

served. These rituals contributed to the maintenance of a sustainable stock in its coastal

fishery. Yet in recent years, with increased outside influence and other social

transformations, traditional values and norms have begun to lose their influence among the

local population. As a result, the traditional rules governing the use of the coastal fishery

have become ineffective. This, together with increasing consumer demands and

extraction activities from the outside world, has led to fast depletion of the fish stock.

In the other case, an aboriginal Atayal tribal community in the mountainous area

was initially faced with a similar challenge as indigenous practices began to lose their

effectiveness as a tool for governing their nearby forests. This tribal community

underwent key social transformations as the local economy became increasingly tied to the

outside economy and Christianity began to displace traditional values and beliefs.

Leaders in the Christian church in this community were able to blend Christian values

with some indigenous beliefs and practices to develop a new cooperative arrangement for

preserving a nearby forest.

Aboriginal Communities and Natural Resource Conservation

biological, and other material conditions affect social institutions and behaviors (Price,

1982). A central argument is that aboriginal peoples tend to develop social institutions,

such as hunting and diet restriction norms, to help them survive in harsh physical and

biological environments (Ross 1978). While this functionalist perspective helps explain

the existence of specific social institutions related to resource use, it is not particularly

helpful in explaining how social institutions evolve, especially when the changes are not

associated with changes in the physical world. In this regard, the political-economic

literature provides a more useful perspective as it understands institutional evolution as not

just a result of changes in physical and biological systems but also strategic choices of and

interactions among individual resource users, in the context of interlocking layers of

institutional influences, various collective learning processes, and distributional conflicts

among resource users (cf. Thelen 1999; Berkes and Turner, 2006). Institutions and

processes for natural resource governance are intricately tied to such issues as economic

development, property rights, cultural preservation, social justice, and democratic

participation.

From a political-economic perspective, residents in rural communities are

motivated to preserve their local resources only if they are able to overcome many

obstacles, for example, by (1) resolving collective-action problems and distributional

arrangements to guard against free-riding behaviors, (3) developing solutions to their

resource governance problems that are compatible with traditional social values and local

socio-economic realities, and (4) gaining recognition from external authorities to have the

rights to govern their local resources (Berkes 1999; Kellert et al. 2000; Ostrom 1990; 1995;

Tang and Tang 2001). As these are difficult obstacles to overcome, not all indigenous

communities are equally successful in preserving their local natural resources. Some

indigenous tribes, for example, lack the social structures and cognitive models for

sustainable use of natural resources (Smith 2001), and some have contributed to local

resource depletion by acting as agents of the state apparatus (Dombrowski 2002).

Among the indigenous communities that are successful in conservation, most have

developed elaborate institutional rules for defining resource boundaries, user rights,

resource allocation rules, monitoring arrangements, conflict-resolution mechanisms, and

more (Ostrom 2005). These institutional rules are supported not just by knowledge of

the local environment, but also by deep-rooted social values and belief systems passed

down through generations (Klooster 2000). In some aboriginal belief systems, natural

resources are considered as gifts from gods, and deserve care and respect from humans. In

some cases, routine social rituals may have evolved for other purposes, but have

contributed to maintaining an effective resource conservation regime (Fowler 2003).

indigenous community becomes exposed to the outside world. These challenges may

come in different forms. For example, when outsiders begin to arrive and make claims

on the resource, traditional allocation rules may begin to lose their effectiveness in

limiting the use of the resource (Tang and Tang 2001). Or, as the local economy becomes moreintegrated with thelargereconomy,localresidents’relianceon thelocalresource

may diminish, creating different incentives for resource use. Another key challenge

concerns the erosion of indigenous belief systems that are supportive of nature

conservation. Once these belief systems become ineffective in constraining social

behaviors, traditional conservation regimes can be undermined easily.

A key question in nature conservation becomes how indigenous communities may

meet these challenges by adjusting their institutional rules, values, and belief systems in

support of effective resource governance. This question has become increasingly

important as many international agencies and governments worldwide are seeking to

devolve governing authority to the local level and to engage indigenous communities in

developing or regenerating self-governing institutions for local natural resource

governance (Ribot and Larson 2005; Natcher and Davis 2007). It is, however, uncertain

if these indigenous communities can effectively shoulder such responsibilities, especially

in a world in which most rural communities, no matter how remote, are inevitably

As argued by Agrawal and Gibson (1999), many usual assumptions about

communities—well-defined territories, small size, stable and homogenous residents,

shared identities and understandings—are no longer the reality in most local resource

governance situations. Indeed, most indigenous communities, no matter how remote, are

inevitably connected to the outside world through various political, social, and economic

linkages. To be successful in conserving their local natural resources, residents in these

communities have to adapt their community-based institutions to these new realities.

In the following two sections, we present the two cases—the Tao communities on

Orchid Island and the Atayal community in Smangus—the former exemplifying on-going

challenges to the resource governing system and the latter, innovative adaptation in such a

transition. In conducting our research on the two cases, we have drawn on a rich

anthropological literature accumulated since the beginning of the twentieth century (Yang

2005).1 This literature provides detailed documentation about many of the social

institutions as well as cultural beliefs and practices examined in this paper. In addition, one

of the authors and several research assistants conducted field research on the island from

2004 to 2006. About two-dozen informants from the two communities were interviewed,

some in person and some on the phone. Informants included tribal elites, ordinary

1

The Tao and Atayal have been the most thoroughly investigated aboriginal tribes in Taiwan. For the Atayal, it has been the least obedient aboriginal tribe to Japanese

colonial rule. The colonial government encouraged studies on this tribe in order to develop means for preventing rebellion. For the Tao, it is for a more scholarly reason. Its geographical isolation and primitive condition made it an ideal investigation site for

residents, and tourists in Smangus, and township-level officials and residents on Orchid

Island.

TheTao Peopleon Orchid Island:No Longer“Blessed” by theEvil Spirits As a branch of the Malayo-Polynesian, the Tao tribe has lived a self-sufficient life

on Orchid Island for about one thousand years (Wong 2001). The island is 45 km2in size

and 88 km from Taiwan Island. Before its opening to outsiders in the 1970s, the island was

largely isolated from the rest of the world because on the one hand, the island itself could

supply everything its inhabitants needed for daily living, except for a few items such as

pottery jars, gold, and silver (to make helmets) for ceremonial performance; on the other

hand, ironically, the island was too poor to be coveted by outsiders (Wei and Liu 1962).2

A key natural resource for the Tao people was the migrating fish found in their coastalfishery. Mostofthem were“flying fish”(Exocoetidae,or“Alibangbang”in the

native language), a general name applied to some twenty fish species in Taiwan and some

forty species worldwide that can glide on the water surface. In spring, large numbers of

flying fish ride on the Kuroshio Current northward. When the fish passed by the island,

the Tao people would be waiting in teams, with several boats from the same community.

Flying fish are quite easy to catch. A convenient way was to light a torch at night, and

2

The population of Tao had been quite stable at about 1,500 until the island was open to outsiders. This was probably due to the scarcity of natural resources. Recently, the population has grown drastically to about 3,500, although about 1,000 migrated to Taiwan Island (Tien 2002, 49).

many fish would jump into the boat. A fishnet could also be stretched between boats to

trap the fish. One way or another, enough fish could be caught for immediate

consumption as well as for later consumption through the entire season after they were

preserved.

The Tao people were organized into six communities. Within each community, there

were several cognate corporate groups, each consisting of siblings and close relatives from

the same bilateral system. Production work associated with land property (such as

agriculture, construction of irrigation facilities, and fishing activities) was mostly limited

to cooperation among members from the same cognate system, while for other types of

work, collaboration (such as house construction) could go across the boundaries of

cognate lineages (Wong 2001). Nevertheless, there was no unitary authority or

permanent chieftainship at the pan-tribe (island-wide), community, or corporate group

level that could significantly affect the conduct of public life.

Many folk laws were in the form of social taboos that were supposed to be enforced by evilspirits(“Anito”in thelocallanguage)thatcould beeverywhereandcould cause

terrible troubles to humans (Kuan 1989; Lee 1986). As such, everyone was well advised

to do anything he or she could to avoid irritating these evil spirits. These taboos were

interwoven with a wide array of other social practices, contributing to the maintenance of

complicated taboos on fishing activities, diet, and fish stock preservation.

To conduct fishing activities in the ocean with strong currents, the Tao needed strong

boats; bigger boats with more oars and greater propelling power were safer than smaller

boats. Thus there were issues regarding boat construction and crew recruitment.

Constructing a boat required precious wood materials that were in short supply on the

island. There were traditional guidelines about what kinds of wood could be used for

which parts of the boat (Chen 2004).3 Many ritual requirements must be met before the boat’svirgin sail;and the ability to fulfill these requirements was usually determined by

the builders’social status and wealth level. To operate the boat, the Tao needed to

organize the crew, which involved many taboos about social relations. Although adopted

for reasons that may not be directly related to conservation, these taboos put serious

constraints on the ability of the Tao to conduct large-scale fishing activities that might

endanger the sustainability of the fish stock.

When both the boats and the crews were ready, there were also complicated taboos on

the actual fishing activities. There were a series of Flying Fish Ceremonies from

February to October. The arrival of flying fish was considered the most important event

for the Tao people. Right after the Fish-Attracting Ceremony, extensive taboos were

3

Many of these taboos are associated with indigenous knowledge. For example, the materials for the keel must be hard wood to prevent damage from percussions and

scratches, while materials for the upper hull should be lighter and softer woods that can keep the boat in balance (Chen 2004, 164; Syaman-Rapongan 2004).

imposed. Specific rules governed the time for the boats to be put on the water, the

specific fishing methods (by torch attraction, rod fishing, or net fishing) to be used, and

the ban against catching other types of fish. Most of these rules were based on

indigenous knowledge and wisdom about the local ecological system. For example,

when the boats were out catching flying fish, no other individual fishing activities were

allowed during the period. This rule enabled other fish species to restore their population

size within about six months.

The most ecologically significant taboo related to the duration in which flying fish

could be served as meals. Each year, the flying fish season ended with the

Fish-Preservation Ceremony in June, and after that all flying fish could be dried and salted

for future consumption. About three months later, however, the Tao people would

conduct the Stop-Dieting-Flying Fish Ceremony and discard all unconsumed flying fish.

It was a strongly-held belief that whoever served the flying fish as a meal after that

ceremony would face immediate misfortune. Although this taboo might have originated

from sanitation and health concerns, it had the effect of turning flying fish into a valueless

object after a defined period, and creating an incentive structure favorable to the

conservation of flying fish.

The authority of these taboos was challenged after Christianity was introduced to the

and they were subsequently able to earn great respect from the islanders. In addition to

bringing such materials as clothes and rice to the island, these missionaries were devoted

to improving the welfare of the islanders, and played a key role in mediating disputes

between natives and the police officers, soldiers, and bureaucrats dispatched from

government agencies in Taiwan Island (Lin 2004). The missionaries have been quite

successful in converting local people to Christianity. Presbyterianism is now the

dominant religion on the island, covering more than 60 percent of the island population,

with Catholicism covering the rest (Chien 2004).

Christianity did not replace the aboriginal belief system immediately. Earlier

missionaries tried to educate local people to live a civilized life under the guidance of the

Bible. Very soon they realized that traditional tribal practices could not be easily

replaced in the short run because they were deeply rooted in many aspects of daily life.

In response, they changed their conversion strategy by tolerating many traditional cultural

values, and by integrating Christian teachings and rituals into indigenous tribal practices,

hoping to change Tao customs and behaviors step by step (Chien 2004, 159-163). As

more and more Tao people were converted to Christianity, the contradiction between

Christianity and traditional taboos became more apparent: for example, when the Christian

God holds supremacy over all supernatural spirits, then a conversion to Christianity will

actually imposed constraints and costs on their individual daily life!

In addition to the erosion of the taboo system, some other factors have triggered

behavioral changes. One example was the introduction of motorboats to the island. As

a goodwill gesture, the local government offered the islanders motorboats in an effort to

improve their fishing efficiency. Motorboats obviously could run much faster and farther

than the traditional hand-rowers. Yet the problem was that motorboats did not require a

lengthy construction process, which in the past added credence to the traditional rituals

and ceremonies; nor did the motorboat require a crew that had a long-term partnership

based on intimate social relations. Although some islanders initially refused to use motor

boats to avoid possible sanctions from the evil spirits, as time went by, more and more

islanders began to appreciate their attractiveness as they did travel much faster and farther,

especially when they faced the competition of the non-Tao surface gillnet fleets nearby.4

What finally made the Tao people embrace the new motorboats was that the Christian

Church offered a whole new belief system in which one could be free forever from

possible harassment by evil spirits. Among those who were most likely to convert to

Christianity were the younger generations, who had been less socialized by the traditional

belief system, were on the lower rank of the social hierarchy, were more constrained and

family.5 They can now ride on the motorboat that provides them with speed, agility, and

expedience, and they can catch flying fish and trade the dried fish to tourists without any

ritual constraints. As more and more motorboats appeared on the fishery, the amount of

flying fish available began to diminish rapidly. According to one estimate, the amount of

flying fish available to islanders has dropped more than 50 percent from less than a decade

ago (Lai 2005). Obviously, Christianity per se did notbring abouta“tragedy ofthe commons.” Theresourcedepletion dangerwasbroughton by increased fishing and roe

collection by non-Tao fishers in the region as well as changes in the institutional

foundations of local appropriation practices. It remains unclear how the Tao people may

respond to this challenge.

The Atayal in Smangus: Guarding the Dark Forest by Reviving Communal Spirit

Thestory oftheAtayalin Smangusisquitedifferentfrom theTao’s. The Atayal

(or“Tayal”,meaning “genuinepeople”in thenativelanguage)tribalpeopleareprobably

the earliest residents of Taiwan, famous for their bravery and agility (Tien 2001, 12).

The tribe had the second largest population among indigenous tribes in Taiwan, and its peopleweremostbroadly spread outin Taiwan’smountainousareas(Allis-Nokan and Yu

2002). Since the Atayal people relied on open space for both millet fields and hunting

5

Since the island is quite small and lacks economic opportunities, most youngsters are longing for opportunities to develop their careers in the Taiwan main island. Taking part in church activities increasesone’schancesto beselected fortraining in seminariesin Taiwan. Interview with a theological college student, Lan Yu, July 24, 2006.

grounds, which might be surrounded by hostile subgroups of Atayal and non-Atayal tribal

groups, they had to manage effectively both internal collective-action problems as well as

external threats.

Atayal tribal members were organized in cohesive groups so that they could share the

chores of patrolling during peacetime and deploying coordinated strategies during hunting

and wartime. They relied on a shared belief system as well as familial relations as the

foundation for solidarity, called “Gaga”in thenativelanguage. In aGaga, a communal

spirit was held by a group of cognate folks who shared the same sacrificial rituals and

ancestral lessons, operated as a functional social unit, and most importantly, were

dedicated to sharing the same fate on personal safety as well as available resources. A

concrete format of a Gaga was a tribal community (Qalang in native language), of about a

hundred people, headed by an elected elder from the core families (Wong 1986, 573).

An integral part of a Gaga is the ancestral belief system. The Atayal belief system

was a mixture of Animism and Ancestralism. The Atayal people believed that everything

was governed by a specific kind of demon that should be respected. Yet also influential

on their fate are the spirits of their dead ancestors. While their concepts about the supernaturalworld aresomewhatsimilarto thoseoftheTao’s,the Atayalplaced more

emphasison thegood spirits,orwhatthey called “Utux”in thenativelanguage,than on