科技部補助專題研究計畫成果報告

期末報告

Clawback 條款是否可以減輕 CEO 對審計委員會監督效率

之影響?

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型計畫

計 畫 編 號 : MOST 102-2410-H-004-023-

執 行 期 間 : 102 年 08 月 01 日至 103 年 08 月 31 日

執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學會計學系

計 畫 主 持 人 : 俞洪昭

報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文

處 理 方 式 :

1.公開資訊:本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,1 年後可公開查詢

2.「本研究」是否已有嚴重損及公共利益之發現:否

3.「本報告」是否建議提供政府單位施政參考:否

中 華 民 國 103 年 11 月 30 日

中 文 摘 要 : 一直以來,獨立性即被視為是審計委員會能否有效履行其法

律所賦予責任的重要基礎。最近的審計研究在探討會傷害審

計委員會獨立性之因素時,發現若公司以認股權做為審計委

員會成員的報酬,公司較容易發生財務報表重編、內控缺失

以及盈餘管理行為。此外,公司若對財務報導的監督越不重

視,越會傾向於採用股票或認股權做為審計委員會成員的報

酬。不同於這些以獎酬為基礎的研究,本研究試圖探討公司

訂定 clawback 條款是否可以降低 CEO 對審計委員會的影

響,進而提高審計委員會對財務報導監督的有效性。

中文關鍵詞: 審計委員會, Clawback 條款, CEO power, 權益基礎報酬

英 文 摘 要 :

Can Clawback Provisions Mitigate CEOs’ Power

on Audit Committee Effectiveness?

Hung-Chao Yu

Professor of Accounting

Department of Accounting

College of Commerce

National Chengchi University

1

1. INTRODUCTION

Audit committees have long been regarded as a vital mechanism to assure the transparency and

integrity of corporate financial reporting (SEC 1974; COSO 1992; Blue Ribbon Committee 1999).

However, recent accounting frauds lead market participants to question the effectiveness of audit

committees in fulfilling their oversight role. Such concerns give rise to the passage of the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX), which expends audit committees’ responsibilities with an aim to

restore the credibility of firms’ financial statements. Among these provisions, audit committee

independence has received much attention by the auditing academics because independence is the

cornerstone based on which audit committees can effectively exercise their duty delegated by SOX

(e.g., Bronson et al. 2009; Lennox and Park 2007; Menon and Williams 2004, 2008; Naiker and

Sharma 2009; Srinivasan 2005). Prior studies have shown that audit committee independence is

associated with stronger monitoring (e.g., Carcello and Neal 2003; Klein 2002a, 2002b), and such

strengthened monitoring further improves earnings quality (e.g., Beasley et al. 2009; Bedard et al.

2004; Srinivasan 2005).

Recent studies turn attention to potential threats that may harm audit committee independence

and show that option compensation paid to audit committee members is associated with higher

likelihood of restatements (e.g., Archambeault et al. 2008), internal control weaknesses (e.g.,

Cullinan et al. 2010), and earnings management (e.g., Bedard et al. 2004). In addition, clients

whose audit committees have larger stock ownership are more likely to dismiss their auditors

following first-time going concern opinion (e.g., Carcello and Neal 2003). Firms demanding less

monitoring over financial reporting pay more equity-based compensation to their audit committees

(e.g., Engel et al. 2010). In contrast to these compensation-based studies, Naiker and Sharma (2009)

test audit committee independence from a revolving-door perspective and finds that former auditor

affiliation contributes to audit committees’ effective monitoring over internal controls. Naiker et al.

(2013) further proves that the 3-year cooling period restriction is not warranted because having

2

Bruyneseels and Cardinaels (2014) finds that only non-professional social ties affect the

appointment of audit committee members, leading to ineffective oversight effectiveness. Different

from these studies, I examine whether firms’ clawback provisions mitigate CEOs’ power on audit

committees, leading to more effective oversight.

My research question is important for two reasons. First, while Section 301 of SOX requires

that all audit committee members should be fully independent when they are newly-appointed to

the boards, this rule does not consider the CEOs’ myriad personal connections in influencing the

selection of audit committee members. Carcello et al. (2011) reports that the monitoring benefits of

reducing the incidence of pre-SOX restatements with independent and financial expert audit

committee members are only maintained when the CEOs are not involved in selecting board

members. Also, the stock market’s unfavorable reaction to restatements is mitigated only when the

audit committee members are independent and the CEOs were not involved in selecting board

members. In light of this potential detrimental effect of CEOs’ power on audit committees’

oversight effectiveness, the NYSE passes a rule (which was finally approved by the SEC on

November 4, 2003 and became effective on January 1, 2004) shortly after the passage of SOX

requiring that only independent board directors assume the responsibility for new director selection.

Therefore, the involvement of CEOs in director selection was formally prohibited in the post-SOX

period. However, Lisic et al. (2011) documents that having financial experts on audit committees

does not necessarily lead to less likelihood of post-SOX restatements because the NYSE’s rule of

prohibiting CEOs from being directly involved in the director selection process may not be

sufficient to ensure audit committee independence. In other words, CEO power continues to have

substantial adverse impacts on audit committees’ oversight effectiveness after the SOX. This may

potentially explain current empirical evidence that, even in the post-SOX era, top management still

exercises significant control over the hiring and firing of external auditors (KPMG 2004; Cohen et

al. 2010; Dao et al. 2012). Given Lisic et al.’s (2011) findings and Carcello et al.’s (2011) argument

3

restatements, a follow-up study that examines what regulatory arrangements may mitigate CEO

power on audit committees’ effectiveness is timely and warranted.

Second, clawbacks are compensation contract provisions that allow companies to recover

bonuses previously awarded to corporate executives in the event of subsequent erroneous financial

reporting. These provisions were first introduced by Section 304 of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX).

Section 304 authorizes the SEC to enforce the call for repayment of bonuses by CEOs and CFOs

when restatements occur due to material noncompliance with companies’ financial reporting

requirements resulting from misconduct. Even though Section 304 is enforceable only by the SEC,

a few listed companies began to establish their clawback provisions since early 2005. On March 26,

2006, the Council of Institutional Investors recommended to the SEC that companies should

include policies for recapturing incentive pay following restatements in the Compensation

Discussion and Analysis of their proxy statements. In response to this suggestion, the SEC revised

the 2006 Disclosure Provision of Regulation S-K, stating that clawbacks constitute a material

element of public companies’ compensation of named executive officers and, therefore, should be

disclosed. Two recent Acts further reinforce the implementation of the clawback provisions. The

first one is Section 111 (b)(2)(B) of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (enacted on

October 3, 2008), which requires standard bonus recovery provisions for all financial institutions

involving troubled asset transactions; the second one is Section 954 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street

Reform and Consumer Protection Act (signed on July 21, 2010), which rules that all listed

companies should have clawback provisions (including stocks and options) imposed on current or

former executives over a three-year period prior to restatements.

1Different from SOX Section 304,

this new Act designates companies’ boards of directors to enforce the clawback provisions and the

clawback targets extend to all executives. Whether clawbacks will change managers’ opportunistic

1

While the SEC has decided to postpone the implementation of Section 954 to early 2013, a notable trend in the development of the clawback provisions is that many listed companies other than financial institutions voluntarily adopted their own provisions to recover bonuses before the Dodd-Frank Act. For example, Addy et al. (2011) reports that 145 S&P 500 companies adopted clawbacks provisions during 2006~2008. A more recent survey done by GMI Analytics shows that more than 75% of the S&P 500 companies initiated clawback provisions by the end of 2013.

4

behavior is not as straightforward as we might expect. On the one hand, clawbacks impose

monetary penalties on the managers who manage earnings. Desai et al. (2006) points out that if

managers know that their fraudulent behavior will be penalized ex post, they are likely to have less

incentive to do ex ante earnings management. Consistent with this notion, Chan et al. (2011) and

Dehaan et al. (2012) both find that firms’ voluntary adoption of clawback provisions are associated

with less likelihood of restatements. On the other hand, clawbacks may not really reduce material

misstatements because it is possible that firms adopt clawback provisions simply to signal the

integrity of their financial statements. This is consistent with the signaling theory that it is costly for

firms with low-quality financial reporting to implement clawbacks if they do not intend to enforce

the provisions at all (Farrell and Rabin 1996). Also, firms’ boards are usually uncertain about

whether they can win lawsuits against misconduct managers to recover the full amount of

compensation. Therefore, whether clawbacks can effectively reduce CEOs’ incentive in

manipulating earnings is an empirical question. In this study, I propose that a firm’s clawback

provisions constitute an “incentive threat” that may discourage the CEO to take advantage of his

powerful influence on audit committees’ overseeing firms’ financial reporting, leading to enhanced

audit committee effectiveness.

I choose abnormal accruals and accrual quality to measure audit committees’ effectiveness

because prior auditing studies have documented that managers’ earnings management generally

give rise to low quality earnings (e.g., Ball and Shivakumar 2005, 2008; Lo 2008; Teoh et al. 1998a,

1998b), and poor earnings quality is highly associated with subsequent restatements (e.g., Livnat

2004; Richardson et al. 2003).

My study makes at least two contributions to the audit committee and clawback literature.

First, while the clawback requirement is not new, there is a lack of research that explores its

efficacy, economic consequences, and limitations. My study provides a first step to examine

whether clawbacks are effective in mitigating CEO power, therefore increasing audit committee

5

effectively mitigate the adverse impacts of CEO involvement in director selection, regulators may

need to accelerate the mandatory adoption of clawbacks in the near future. Importantly, regulators

may also consider (a) the tradeoff between prohibiting CEO involvement in director selection and

adopting clawback provisions in executives’ compensation contracts, and (b) whether clawbacks

complement the NYSE’s 2003 rule that only independent board directors can select new directors.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses prior studies related to

my study. Section 3 presents the hypothesis development. Section 4 describes the basic research

design, including the measures of dependent and independent variables, the econometric models,

and the sample selection procedures. Section 5 reports the empirical results and Section 6

concludes.

2. RELATED LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Audit committee Independence and Financial Reporting Quality:

Early studies have examined the association between audit committee independence and

earnings management using pre-SOX data. However, the empirical results are mixed. For example,

Klein (2002a) shows that the magnitude of abnormal accruals is negatively related to audit

committee independence (measured by the percentage of outsiders) only when the majority, rather

than 100 percent, of the members are independent. In a similar study, Bedard et al. (2004) finds that

high discretionary accruals are negatively associated with 100 percent, rather than 50 percent,

independent audit committees (measured by the number of outsiders and whether members are

compensated by options). In contrast to these studies, Xie et al. (2003) documents that the level of

audit committee independence (measured by the percentage of outsiders) is not related to current

discretionary accruals.

In a different strand, Carcello and Neal (2000) examines the relation between audit committee

independence and auditors’ report types. They find that firms with greater percentage of affiliated

directors on their audit committees are less likely to receive a going-concern opinion. Carcello and

6

following a new going concern opinion. The empirical results indicate that audit committee

members having more stock holdings are more likely to dismiss auditors after first-time going

concern reports.

A potential problem with these pre-SOX studies is that they measure audit committee

independence using the percentage of outsiders (who may or may not own firms’ shares). This

“insiders (or affiliated directors) vs. outsiders” dichotomy may be appropriate before SOX because

the exchanges’ listing requirements allowed the appointment of inside-affiliated directors to the

audit committees if it is in the best interests to the companies (Klein 2002b; NYSE Rule

§303.01[B][3][b]; NASDAQ Rule 4310[c][26][B][ii]). Due to this flexibility in audit committee

composition, it was common before 1999 that many audit committees did not have fully

independent outside directors (Klein 1998, 2002b; Vicknair et al. 1993). This creates a setting in

which audit committee members’ equity holdings changed not only because of the equity-based

compensation they received, but also because of inside-affiliated directors’ own shares before they

became audit committee members. Under this setting, an examination of whether equity-based

compensation jeopardizes AC independence may be trivial.

In contrast, Section 301 of SOX requires that audit committees be composed entirely of

independent directors. This provision changes audit committee independence research in three

substantial ways. First, it creates a cleaner setting in which audit committee members’ equity

ownership exists purely from the equity-based compensation. Second, the issue of whether earnings

management is associated with the majority or 100 percent of the independent audit committee

members is no longer important. Finally, even though SOX imposes stringent rules on audit

committees’ composition, expertise, and duties, it is silent in how audit committees should be

compensated to maintain their independence over time. Therefore, an investigation of the

association between equity-based compensation and audit committee independence becomes

important.

7

(2008) uses pre-SOX data to test whether options for audit committees are associated with

restatement likelihood. They find a positive relation for both short-term and long-term options

because short-term options induce audit committee members’ short-term orientation that possibly

undermines their independence, while long-term options are highly uncertain that the payoffs may

be too small to induce audit committee members to monitor financial reporting effectively.

Similarly, Cullinan et al. (2010) uses post-SOX data and shows that firms paying options to their

audit committees are more likely to report ICW. In contrast, Engel et al. (2010) uses both pre- and

post-SOX data and finds that firms are more likely to structure audit committee compensation

toward a fixed pay when there is a high demand for monitoring. Specifically, the level of audit

committee compensation increases after SOX.

My study differs from these recent studies in that, using equity-based compensation to capture

audit committees’ independence impairment, I follow Carcello et al.’s (2011) and Lisic et al.’s

(2011) findings that CEO power persistently influences audit committees’ independence and

propose that the adoption of clawback provisions may mitigate such adverse impact. Currently,

empirical evidence on this issue is rare.

2.2 Clawback Provisions and Financial Reporting Quality:

While there is an increase in voluntary adoption of the clawback provisions, only few studies

have examined different aspects of such provisions. For example, Chan et al. (2011) reports that

restatement likelihood declines after companies voluntarily adopt the clawback provisions. Also,

investors and auditors regard the adoption of these provisions as signal of increased financial

reporting quality. Chan et al. (2012) further shows that, while firms adopting clawback provisions

reduce their accrual management, they tend to switch to real transaction management due to

pressure to meet or beat earnings benchmarks. Similar to Chan et al. (2011), Dehaan et al. (2012)

finds significant improvements in both actual (proxied by restatement likelihood) and perceived

(proxied by ERC) financial reporting quality following clawback adoption. In another study, Addy

8

oversight. Also, these companies have smaller accruals and have directors sitting on other boards of

other companies who have adopted clawback provisions. Finally, Levine and Smith (2010) uses the

agency theory to show that clawbacks are effective only when the cash realization is less noisy,

managing earnings is relatively easy, and the agent is patient.

Even though Chan et al. (2012) indicates that clawbacks may have unintended consequences

for firms whose managers suffer high pressure to meet or beat earnings benchmarks, my study

intends to show that firms could benefit from clawback provisions when these firms’ CEOs have

greater power in selecting board directors.

3. HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Carcello et al. (2011) shows that audit committees that are independent in fact and that possess

financial expertise are associated with reduced likelihood of restatements. Since they use

restatements announced before SOX (i.e., 1999~2001), they measure audit committee

independence by a dummy variable which equals 1 if 100% of the audit committee members are

independent and 0 otherwise. Due to Section 301 of SOX, however, all audit committee members

should be fully independent after SOX. This is why Lisic et al. (2011), which uses restatements

announced during 2004~2005, does not consider audit committee independence in their analyses.

Because I expect that CEO power in board selection will impair the overall beneficial effect of

independent and expert audit committees, I first follow Carcello et al. (2011) by demonstrating the

expected association between audit committee independence (measured by two accrual-based

measures) and accounting expertise, apart from CEOs’ power.

Two recent studies examine the association between equity-based compensation paid to their

audit committee members and firms’ financial reporting quality. Archambeault et al. (2008)

empirically documents that both short-term and long-term options are positively associated with

restatement likelihood. Magilke et al. (2009) experimentally shows that a stock-type compensation

is harmful to audit committees’ objectivity judgment toward managers’ aggressive financial

9

independence, leading to worsened financial reporting quality. This causality is supported by two

reasons. First, regulators and the press have expressed serious concerns about whether equity-based

compensation compromises audit committee independence because stocks and options tie audit

committee members’ wealth to firms’ short-term and long-term financial performance (e.g., Barrier

2002; Higgs 2003; Millstein 2002; New York Times 2007; Financial Reporting Council 2003; Wall

Street Journal 2006). Second, DeZoort et al.’s (2002) audit committee effectiveness model and

prior auditing studies (e.g., Abbott et al. 2004; Beasley 1996; Carcello et al. 2002; Kalbers and

Fogarty 1993) indicate that independence is an important factor that influences audit committee

effectiveness. I thus assume that the objectivity of audit committee members in exercising their

oversight duties may decrease when their compensation create conflicts that induce them to

compromise independence. Therefore, I test the following hypothesis (expressed in alternative

form):

H1: Equity-based compensation paid to audit committees is positively associated with

firms’ earnings management.

Some early studies have found that the broadly defined financial expertise is negatively

associated with firms’ financial reporting quality (e.g., Abbott et al. 2004; Agrawal and Chadha

2005). Carcello et al. (2011) and Lisic et al. (2011) also focus on financial expertise and show that

CEO power weakens the monitoring benefits of such expertise. Since more recent studies show that

it is the narrowly defined accounting expertise that enhances audit committees’ oversight

effectiveness (e.g., Krishnan and Visvanathan 2008; Beasley et al. 2009; Dhaliwal et al. 2010), I

deviate from Carcello et al. (2011) and Lisic et al. (2011) and test my second hypothesis (expressed

in alternative form):

H2: Audit committee members’ accounting expertise is negatively associated with

firms’ earnings management.

Because I use equity-based compensation to capture the impairment of audit committee

10

further jeopardizes audit committee independence. This leads to my third hypothesis (expressed in

alternative form):

H3: The positive association between equity-based compensation paid to audit

committees and firms’ earnings management is enhanced when CEOs have power

in board director selection.

Similarly, the accounting expertise of audit committee members may not result in improved

oversight effectiveness if the CEOs participate in the director selection process. This leads to my

fourth hypothesis (expressed in alternative form):

H4: The negative association between audit committee members’ accounting expertise

and earnings management is reduced when CEOs have power in board director

selection.

The main purpose of this study is to examine whether the clawback provisions can mitigate the

adverse effect of CEOs’ power on audit committees’ oversight effectiveness. Therefore, I posit the

following two hypotheses (expressed in alternative form):

H5: The adoption of clawback provisions mitigates the adverse impact of CEO power

on the positive association between equity-based compensation paid to audit

committees and firms’ earnings management.

H6: The adoption of clawback provisions mitigates the adverse impact of CEO power

on the negative association between audit committee members’ accounting

expertise and firms’ earnings management.

4. RESEARCH DESIGN

4.1 Empirical Models:

Since I will match firms voluntarily adopting the clawbacks with firms that do not initiate

clawbacks, I will adopt the matched-pairs (conditional) logistic regression models (Hosmer and

Lemeshow 2000) to test hypotheses H1 and H2. In these models, I use the relative weight of

equity-based compensation (including stocks and options) in the total compensation packages to

capture how the portions of equity-based compensation impair audit committee independence. I

11

(Bowen et al. 2010; Linck et al. 2009). The following regression model (1) is used:

t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i TENURE AGE MB BDINDEP BDSIZE BIG LnASSET ind ROA ZSCORE ES MEETINGTIM ACSIZE ACCEXP EQUITY AQ DA ABS , , 13 , 12 , 11 , 10 , 9 , 8 , 7 , 6 , 5 , 4 , 3 , 2 , 1 , 4 _ % / _

(1)

where

ABS_DA = The absolute value of abnormal accrual (adjusted by ROA) measured by

Cohen and Zarowin (2010);

AQ = Standard deviation of the residuals of firm-level time-series model (5) specified

in Dechow and Dichev (2002) over a rolling four-year period;

EQUITY % = Ratio of equity-based compensation to total compensation;

ACCEXP = Ratio of the number of AC members who are CPA or have

accounting-related experience to AC size;

ACSIZE = Number of AC members;

MEETINGTIMES = The number of yearly AC meetings;

ZSCORE = The deciles rank of Altman’s (1968) Z-score;

ROA_ind = The industry-median-adjusted return on assets;

LnASSET = Natural log of a company’s total assets;

Big4 = An indicator variable that equals 1 if a company’s year t financial statements

are audited by a Big 4, and 0 otherwise;

BDSIZE = Natural log of the number of total board directors;

BDINDEP = Percentage of non-AC directors who are independent;

MB = Company’s market-to-book ratio;

AGE= Natural log of the number of years a firm has been publicly traded;

TENURE = Natural log of auditor tenure;

= the residual term.

The dependent variables are abnormal accruals (labeled ABS_DA) and accrual quality (labeled

AQ). The two key variables of interest are EQUITY% and ACCEXP. The first variable EQUITY% is

measured by the ratio of equity-based compensation to total compensation a firm pays to its audit

committee members. Note that, because of a lack of theory explaining the association between

equity-based compensation and audit committees’ oversight effectiveness, predicting the sign of

EQUITY% is not as straightforward as it might seem. Specifically, even though the agency theory

12

shareholders (Dalton et al. 2003; Hillman and Dalziel 2003; Monks and Minow 2001), leading to

more effective monitoring, this prediction may not be applicable to audit committees due to the

conflicting roles they play on the boards. Further, recent studies have documented inconsistent

results. For example, Archambeault et al. (2008) empirically shows that both short-term and

long-term options are associated with higher likelihood of restatements. However, Magilke et al.

(2009) experimentally shows that short-term and long-term options motivate audit committees to

prefer aggressive and overly conservative financial reporting, respectively. In light of the potential

problem of the agency theory and the mixed evidence to date, I choose to base my predictions on

the notion of economic bonding and assert that equity-based compensation increases the economic

dependence of audit committees on the managers because audit committee members’ wealth is tied

closely with firms’ reported performance. Economic bonding thus creates vested interests to audit

committee members in such a way that they may sacrifice their oversight objectivity. Following

this economic bonding notion, hypothesis H1 predicts the coefficient on EQUITY% to be positive.

The second key variable is ACCEXP. Prior research has shown that it is the accounting

expertise, rather than the broadly-defined financial expertise, that improves audit committees'

oversight effectiveness (e.g., Archambeault and DeZoort 2001; Bédard et al. 2004; Goh 2009;

Krishnan 2005; Krishnan and Visvanathan 2008; Raghunandan et al. 2001). Recent studies further

examine whether narrowly-defined accounting and finance expertise individually contributes to

audit committees’ monitoring activities (e.g., Dhaliwal et al. 2010; Engel et al. 2010; Goh 2009).

Following DeFond et al. (2005), I measure ACCEXP by the percentage of audit committee

members having pure accounting expertise only. Accounting experts are members who have CPA

licenses or with accounting-related experience (e.g., accountants, auditors, controllers, CFO, or

chief accounting officers). Since more specialized skills in accounting contribute to audit

committees’ oversight effectiveness (Agrawal and Chadha 2005; DeFond et al. 2005; McDaniel et

al. 2002), hypothesis H2 predicts the coefficient on ACCEXP to be negative.

13

management. Similar to previous studies (e.g., Dechow et al. 1996; Richardson et al. 2003; Desai et

al. 2006), I control for company size (denoted by LnASSET) and predict its coefficient to be

negative because size might capture firm-specific risk (Fama and French 1997) and larger

companies are more likely to be subjected to closer scrutiny by regulators and investors (Balsam et

al. 2003; Romanus et al. 2008). Also, controlling for size can potentially mitigate the problem of

correlated omitted variables (Myers et al. 2005; Ahmed and Goodwin 2007). Further, Beasley

(1996) and Abbott et al. (2004) show that new public companies may encounter difficulty with

SEC-enforced reporting requirements and may not have commensurate financial reporting controls

established. In contrast, Ashbaugh-Skaife et al. (2007) points out that firms with rapid growth are

more likely to fail to keep pace with increases in customer demand or entry into new markets.

Furthermore, growing firms are more likely to encounter staffing issues as the scope and

complexity of their operations expand. Accordingly, I predict a negative coefficient on AGE and a

positive coefficient on MB.

Corporate boards are responsible for monitoring managerial performance in general, and

financial reporting in particular (a task that is delegated to the audit committees). I thus include two

measures to proxy for a company’s governance environment: BDSIZE and BDINDEP. Yermack

(1996) and Eisenberg et al. (1998) report a negative relation between firms’ profitability and board

size because larger boards are more likely to have more issues in coordination, controls, and

free-riders. Because firms with poor performance are more likely to manage their earnings, I

predict the coefficient on BDSIZE to be positive. In contrast, Beasley (1996) and Dechow et al.

(1996) find that outside independent directors are effective monitors of managerial actions. Thus a

negative association between BDINDEP and earnings management is expected.

Farber (2005) reports a smaller proportion of brand-name audit firms in fraud companies

compared with control companies. Therefore, I include Big 4 CPA firms (denoted by BIG4) to

control for auditors’ industry leadership and predict its coefficient to be negative. Furthermore,

14

associated with improved financial reporting quality due to auditors’ increased knowledge and

expertise with their clients, I consider TENURE and predict its coefficient to be negative.

Since financial condition usually affects the likelihood of restatement (Abbott et al. 2004;

DeFond and Jiambalvo 1991; Kinney and McDaniel 1989), I control for this characteristic using

two proxies: ZSCORE and ROA_ind. I consider ZSCORE because Palmrose and Scholz (2004)

shows that companies restating core earnings have higher frequencies of subsequent bankruptcy

and Abbott et al. (2004) uses Z scores as an indicator of financially distressed companies. By

definition of the Z scores, I predict the coefficient on ZSCORE to be positive. I also consider

industry-median-adjusted return on assets (donated by ROA_ind) and predict its coefficient to be

negative because more profitable companies are less likely to manage earnings (Ettredge et al. 2010;

Kinney and McDaniel 1989; Loebbecke et al. 1989; Scholz 2008).

I control for two determinants that may influence the oversight effectiveness of audit

committees: ACSIZE and MEETINGTIMES. I consider ACSIZE because larger audit committees

are perceived to have increased power (Chen and Zhou 2007; Kalbers and Fogarty 1993) and are

more likely to challenge top management and internal control personnel in fulfilling their

monitoring responsibilities (Goh 2009; Krishnan 2005). I also consider MEETINGTIMES to

capture audit committees' effort (Engel et al. 2010) because more diligent audit committees are

more likely to effectively exercise their oversight duties (DeZoort et al. 2002) so that they can

remain informed of accounting and auditing issues (Raghunandan et al. 2001).

I will next examine whether the negative effect of equity-based compensation (which harms

audit committee independence) is enhanced and whether the positive effect of accounting expertise

is attenuated due to CEO power in the director selection process (i.e., hypotheses H3 and H4,

respectively). To do this, I will include CEO power (denoted by CPOWER) and its interactions

with EQUITY% and ACCEXP into model (1). Following Lisic et al. (2011), variable CPOWER is a

summary index consisting of nine CEO characteristics that incorporate four major dimensions of

15

(1) CEO’s formal position in a company (i.e., the structural power):

(a) Relcomp = CEO’s cash compensation (including fixed salary plus bonus) divided by

the company’s highest executive’s cash compensation excluding the CEO;

(b) Dual = 1 if the CEO is also the chairman of the board and 0 otherwise;

(2) CEO’s ownership in a company (i.e., the ownership power):

(a) Share% = Percentage of CEO’s share ownership;

(b) Founder = 1 if the CEO is also the founder of the company and 0 otherwise.

(3) CEO’s expertise and capability (i.e., the expert power):

(a) Tenure = Number of years a director has been serving as the CEO position;

(b) NumExec = Number of years a director has been serving as an executive position

(including president, CFO, COO, vice president, vice chairman with administrative

duties, and general manager);

(c) YearExec = Number of years a director holds both an executive and a CEO positions.

(4) CEO’s social networking ability (i.e., the prestige power):

(a) CorpBD = Number of other firms’ board members the CEO holds;

(b) EliteEd = 0 if the CEO did not receive any formal higher education, 1 if neither the

CEO’s undergraduate nor graduate institution is elite, 2 if the CEO’s undergraduate or

graduate (but not both) institution is elite, and 3 if the CEO’s undergraduate and

graduate institutions are both elite. While Lisic et al. (2011) adopts Finkelstein’s

(1992) list of 26 schools to identify whether an institution is elite, I expand this list

using the top 50 world’s best universities prepared by the US News and World Report

(2012). This is because many of the large US companies are now hiring their

executives from around the world rather than focusing on Americans only.

Obviously, the higher these measures, the stronger the CEO power. All of the above

16

above the sample median is coded 1and 0 otherwise. I then add up the values of all the dichotomous

variables to create my index variable CPOWER. By definition, CPOWER ranges from 0 (the lowest

CEO power) to 9 (the highest CEO power). I thus plug this new variable and its interactions with

EQUITY% and ACCEXP into the following conditional logistic regression model (2):

t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i TENURE AGE MB BDINDEP BDSIZE BIG LnASSET ind ROA ZSCORE ES MEETINGTIM ACSIZE ACCEXP CPOWER EQUITY CPOWER CPOWER ACCEXP EQUITY AQ DA ABS , , 16 , 15 , 14 , 13 , 12 , 11 , 10 , 9 , 8 , 7 , 6 , 5 , 4 3 , 2 , 1 , 4 _ % % / _

(2)

In the above model, the coefficient on EQUITY% captures the association between audit

committees’ equity-based compensation portion and earnings management when the CEOs do not

have power in selecting the directors. The coefficient on CPOWER

EQUITY% tests whether the

association between audit committees’ equity-based compensation portion and earnings

management differs when the CEOs have power in the director selection process. Hypothesis H3

can be tested by examining whether the coefficient on CPOWER

EQUITY% is significantly

positive.

Similarly, the coefficient of ACCEXP measures the association between audit committees’

accounting expertise and earnings management when the CEOs do not have power in selecting the

directors. The coefficient on CPOWER

ACCEXP tests whether the association between accounting

expertise and earnings management differs when the CEOs are involved in the director selection

process. Again, hypothesis H4 can be tested by examining whether the coefficient on

CPOWER

ACCEXP is significantly positive.

Empirically, the support of my hypotheses H3 and H4 shall confirm Carcello et al. (2011) and

Lisic et al. (2011). Since the main purpose of this study is to propose that the adoption of clawback

provisions may mitigate the adverse effects of CEOs’ power on audit committee independence and

17

voluntarily adopts the clawback provisions in a given year t and 0 otherwise. I then include this

variable and its interactions into the following conditional logistic regression model (3):

t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i t i TENURE AGE MB BDINDEP BDSIZE BIG LnASSET ind ROA ZSCORE ES MEETINGTIM ACSIZE CB ACCEXP CPOWER CB EQUITY CPOWER CB CPOWER ACCEXP CPOWER EQUITY CPOWER CPOWER ACCEXP EQUITY AQ DA ABS , , 19 , 18 , 17 , 16 , 15 , 14 , 13 , 12 , 11 , 10 , 9 , 8 , 7 , 6 , 5 , 4 3 , 2 , 1 , 4 _ % % % / _

(3)

In the above model, the coefficient on CPOWER

CB tests whether the overall effect of CEO

power on earnings management is reduced by the adoption of clawback provisions. To the extent

that clawback provisions discourage CEOs’ use of their power in influencing audit committee’s

monitoring duties, I predict the coefficient on CPOWER

CB to be negative. Furthermore,

coefficients on CPOWER

EQUITY%

CB and CPOWER

ACCEXP

CB test whether the adverse

impacts of CEO power on audit committee independence and accounting expertise reduce when

firms voluntarily adopt the clawback provisions. Hypotheses H5 and H6 thus predict both

coefficients to be negative.

4.2 Data and Sample Selection:

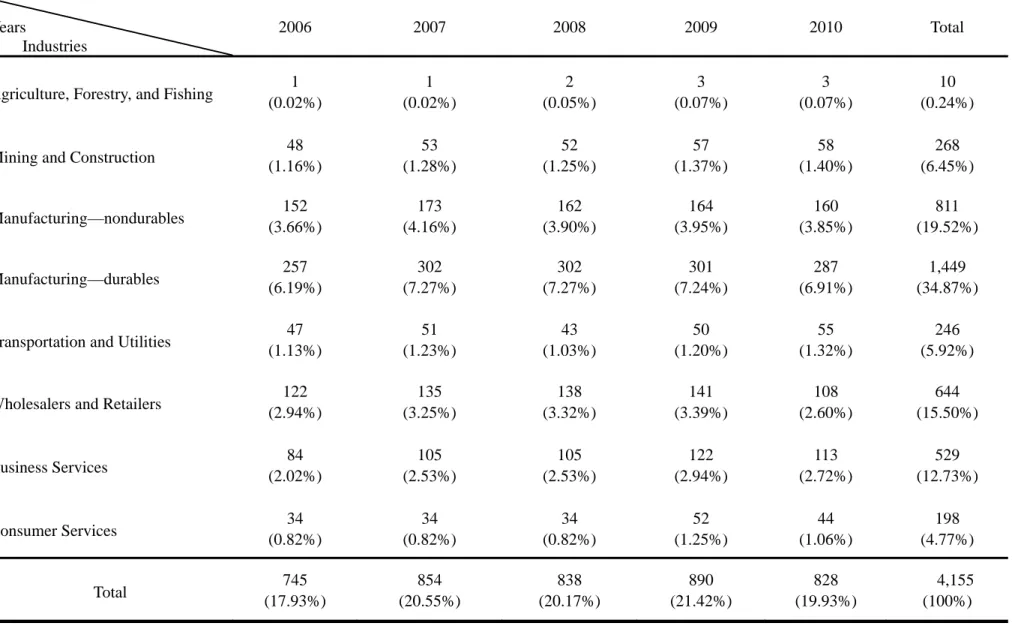

The original sample consists of hand-collected 3,895 S&P 500 firm observations during fiscal

years from 2003 to 2012. Year 2012 is included because the SEC has not yet to make its final

decision as to when and how to implement Section 954 of the Dodd-Frank Act by the end of 2012.

Therefore, all extant clawback provisions should be voluntary in nature. Each sample firm’s

financial data are collected from COMPUSTAT. Data on voluntary clawback provisions are

collected from the GMI Analytics. Twenty-eight financial institutions that received the U.S. federal

bailout funds in 2008 and 2009 are excluded because these financial institutions were subjected to

mandatory clawbacks enforced by the Department of Treasury under the Emergency Economic

Stabilization Act of 2008.

18

information, board size, and board independence are collected from BoardEx. We exclude 52 firm

observations with missing data in BoardEx. Because the proxy statements provide only limited

information regarding CEOs’ education background, I supplement the data from Business Week,

Forbes, nndb.com, and www.zoominfo.com. Finally, we exclude 1,497 firm observations with

missing data on COMPUSTAT and ExecuComp. The final sample consists of 2,318 firm

observations. Table 1 reports the sample selection process.

[Insert Table 1 here]

I restrict my sample to companies whose fiscal year ends on December 31 to make the sample

companies as homogenous as possible. To control for outlier problem, I winsorize observations that

fall in the top and bottom 1 percent of the empirical distribution for both the dependent and

independent variables (Bulter et al. 2005; Fan and Wong 2005).

Two major equity-based compensation components will be examined: stock awards, which

include common stock with and without restrictions, deferred stock units, and phantom stock units;

option grants, which include short-term and long-term stock options. The value of stocks will be

determined by multiplying the number of shares awarded by the closing price. Following Brick et

al. (2006) and Core et al. (1999), I compute option values using the 25 percent of their exercise

price or the closing market price on the annual meeting date if exercise price is not available.

5. EMPIRICAL RESULTS

5.1 Descriptive Statistics:

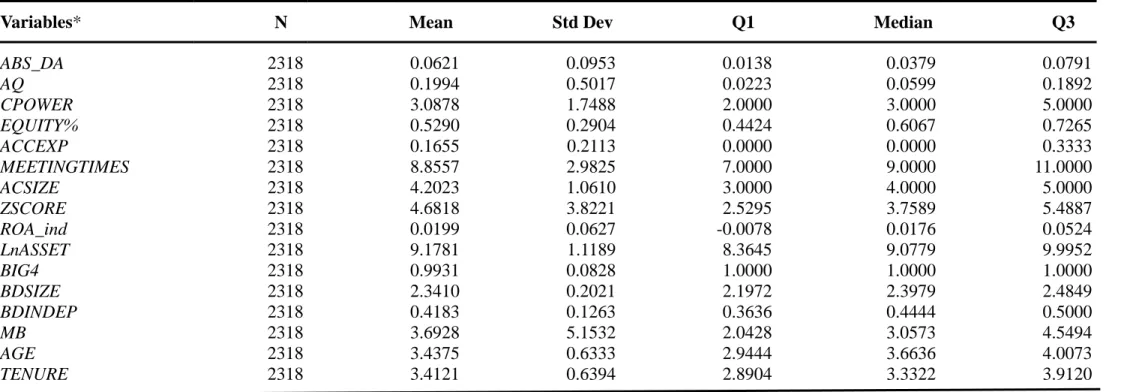

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the full sample. The mean values of ABS_DA and

AQ are 0.0621 and 0.1994. These are comparable to those reported in prior studies. On average, the

audit committee has four directors and meets roughly 9 times per year. The mean value of the

proportion of audit committee members with pure accounting expertise is 16.7%. In addition,

nearly 99% of the observations are audited by a Big 4 auditor. About 41.8% of the board members

19

the proportion of equity-based compensation to total compensation awarded to audit committee

members is about 52.9%, suggesting that firms pay relatively less cash to their audit committee

members.

[Insert Table 2 here]

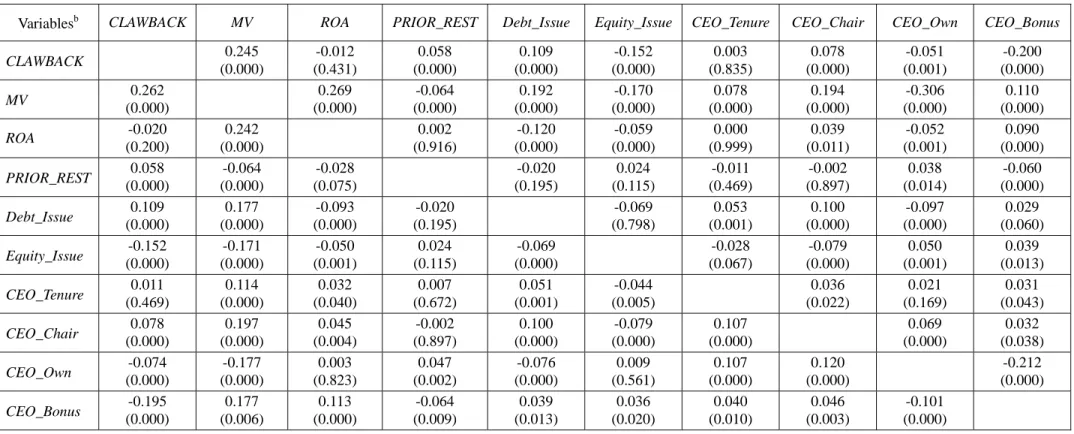

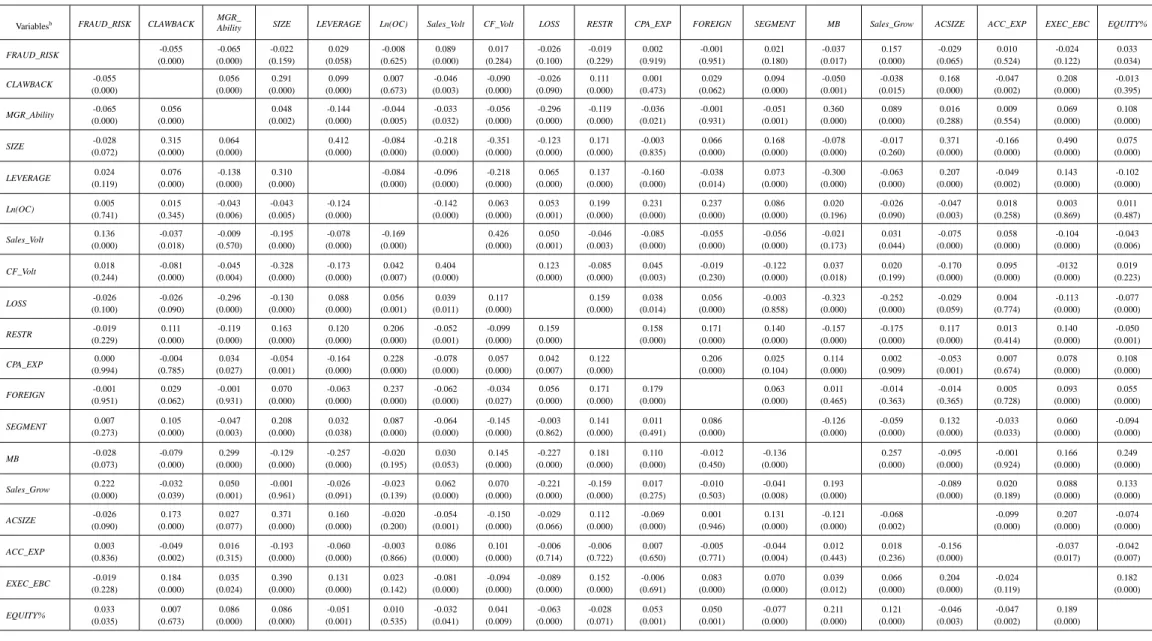

5.2 Regression Results:

Results of models (2) and (3) are in Table 3. In both models, the adjusted R

2’s are 0.216 and

0.218 and the F-statistics are significant at the 0.01 level, indicating that collectively, the models

have explanatory power in explaining variations in abnormal accruals. Consistent with Krishnan

and Yu (2014), the coefficients on EQUITY% are positive and significant at the two-tailed 0.01

level, suggesting that the proportion of total compensation that is equity-based paid to audit

committee directors has a negative effect on earnings quality. Therefore, our hypothesis H1 is

supported. Also consistent with prior research, the coefficients on ACCEXP are negative and

significant at the two-tailed 0.10 level, indicating that earnings quality is increasing in audit

committee’s accounting expertise (Krishnan and Visvanathan 2008; Dhaliwal et al. 2010). This

result, which supports our hypothesis H2, underscores the importance of audit committee’s

accounting expertise in improving firms’ earnings quality.

[Insert Table 3 here]

Turning to CEO power variables, the coefficients on CPOWER are positive and significant

at the 0.01 level, suggesting that firms with higher level of CEO power are more likely to incur

earnings management. Importantly, the coefficients on the interaction term CPOWER

EQUITY%

are positive and significant at the 0.01 level. This result supports our hypothesis H3, indicating that

the adverse effect of equity-based compensation paid to audit committees on earnings quality is

enhanced when CEOs have higher level power. In contrast, the coefficients on the interaction

CPOWER

ACCEXP are positive and significant at the 0.05 level. This result supports our

hypothesis H4, suggesting that high CEO power moderates the negative association between audit

20

shows equity-based compensation impairs the effect of audit committee’s accounting expertise on

earnings quality, my study shows that CEO power could be another threat to the efficacy of audit

committee members’ accounting expertise in overseeing firms’ financial reporting.

To test whether the adoption of clawback provisions could mitigate the adverse impact of

CEO power on firms’ earnings quality, we include CB and its interactions into model (2). As shown

on the right column of Table 3, the coefficient on CPOWER

CB is negative and significant at the

0.01 level, implying that the adoption of clawback provision by itself can mitigate the negative

effect of CEO power on earnings quality. Looking a step further, the coefficients on

CPOWER

EQUITY%

CB and CPOWER

ACCEXP

CB are both negative and significant at least

at the 0.05 level. In other words, firms’ adoption of clawback provisions mitigates the adverse

impact of CEO power not only on the positive association between equity-based compensation paid

to audit committees and earnings management but also on the negative association between audit

committees’ accounting expertise and earnings management. Therefore, my hypotheses H5 and H6

are supported.

As a sensitivity test, I also use accrual quality as the dependent variable and re-run all

analyses. The results, as reported in Table 4, are much similar to those shown in Table 3.

Accordingly, my findings are robust to different earnings quality measures.

2[Insert Table 4 here]

6. CONCLUSIONS

I extend prior research on the potential detrimental impact of CEO power on audit committee

effectiveness by examining whether CEO power enhances the negative effect of equity-based

compensation and impairs the positive effect of accounting expertise on audit committee

2

My results shall not be driven by firms that pay excessive equity-based compensation for three reasons. First, I have trimmed observations in the top and bottom 1% of the distributions of continuous variables. Therefore, observations with extreme high EQUITY% have been excluded from the sample. I have re-run the analyses without deleting these outliers and the results remain the same. Second, since EQUITY% is bounded between zero and one, extreme EQUITY% may not affect the empirical results in a substantial way. Finally, the descriptive statistics indicate that EQUITY% seems to be evenly distributed (see Table 2).

21

effectiveness. Notwithstanding the recent regulatory reforms requiring a completely independent

nominating committee, I expect that the monitoring effectiveness of audit committees will depend

on overall CEO power. I first show that equity-based compensation harms audit committee

effectiveness, leading to worse earnings quality. I then show that pure accounting expertise

enhances audit committees’ effectiveness in mitigating firms’ earnings management behavior.

Using a summary index for CEO power, I find that CEO power strengthens the adverse effect of

equity-based compensation and weakens the positive effect of pure accounting expertise. Finally, I

show that the adoption of clawback provisions can successfully mitigate the negative effect of CEO

power, leading to reduced equity-based compensation effect and increased accounting expertise

22

REFERENCES

Abbott, L. J., S. Parker, and G. F. Peters. 2004. Audit committee characteristics and restatements.

Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 23 (1): 69–87.

Addy, N.D., X.Y. Chu, and T.R. Yoder. 2011. Recovering bonuses after restated financials:

Adopting clawback provisions. Working Paper, Mississippi State University.

Agrawal, A. and S. Chadha. 2005. Corporate governance and accounting scandals. Journal of Law

and Economics 48 (2): 371-406.

Ahmed, K. and J. Goodwin. 2007. An empirical investigation of earnings restatements by

Australian firms. Accounting and Finance 47 (1): 1–22.

Archambeault, D. and F.T. DeZoort. 2001. “Auditor Opinion Shopping and the Audit Committee:

An Analysis of Suspicious Auditor Switches.” International Journal of Auditing 55 (1):

33–52.

Ashbaugh-Skaife, H., D. Collins, W. Kinney, and R. LaFond. 2007. The discovery and reporting of

internal control deficiencies prior to SOX-mandated audits. Journal of Accounting and

Economics 44 (1/2): 166–92.

Archambeault, F.T. Dezoort, and D. Hermanson. 2008. Audit Committee Incentive Compensation

and Accounting Restatements. Contemporary Accounting Research 25 (4): 965–92.

Baldwin, T. and D. Yoo. 2005. Traversing shaky ground: An analysis for investors. Yellow Card

Trend Alert. Glass Lewis & Co., LLC.

Ball, R., and L. Shivakumar. 2005. Earnings quality in UK private firms: Comparative loss

recognition timeliness. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 83-128.

Ball, R., and L. Shivakumar. 2008. Earnings quality at initial public offerings. Journal of

Accounting and Economics 45: 324-349.

Balsam, S., J. Krishnan, and J. S. Yang. 2003. Auditor industry specialization and earnings quality.

Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 22 (3): 71–97.

Barrier, M. 2002. The compensation balance. Internal Auditor 59 (3): 42–7.

Beasley, M. S. 1996. An empirical analysis of the relation between the board of director

composition and financial fraud. The Accounting Review 71 (2): 443–65.

Beasley, M.S., J.V. Carcello, R. Hermanson, and T. Neal. 2009. The audit committee oversight

process. Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (1): 65–122.

Bedard, J.C., S.M. Chtourou, and L. Courtean. 2004. The effect of audit committee expertise,

independence, and activity on aggressive earnings management. Auditing: A Journal of

Practice & Theory 23 (2): 13–35.

Blue Ribbon Committee on Improving the Effectiveness of Corporate Audit Committees. 1999.

Report and recommendations of the Blue Ribbon Committee on improving the

effectiveness of corporate audit committees. New York, NY: NTSE and NASD.

Bowen, R.M, C.C. Andrew and S. Rajgopal. 2010. Whistle-blowing: Target firm characteristics

and economic consequences. The Accounting Review 85 (4): 1239–1271.

Brick, I. E., O. Palmon and J. K. Wald. 2006. CEO Compensation, director compensation, and firm

performance: Evidence of cronyism. Journal of Corporate Finance 12 (3): 403-423.

Bronson, S., J. Carcello, C. Hollingsworth, and T. Neal. 2009. Are fully independent audit

committees really necessary? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 28 (4): 265–80.

23

Butler, M., A. J. Leone, and M. Willenborg. 2004. An empirical analysis of auditor reporting and its

association with abnormal accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 37 (1): 139-165.

Burks, J. 2011. Are investors confused by restatements after sarbanes-oxley? The Accounting

Review 86 (2): 507–539.

Carcello, J. V., and T. L. Neal. 2000. Audit committee composition and auditor reporting. The

Accounting Review 75 (4): 453-467.

Carcello, J.V., D. R. Hermanson and T. L. Neal. 2002. Disclosures in audit committee charters and

reports. Accounting Horizons 16 (4): 291-304.

Carcello, J. V., and T. L. Neal. 2003. Audit committee characteristics and auditor dismissals

following ‘‘new’’ going-concern reports. The Accounting Review 78 (1): 95–117.

Carcello, J. V., and A. L. Nagy. 2004. Client size, auditor specialization and fraudulent financial

reporting. Managerial Auditing Journal 19 (5): 651–668.

Carcello, J. V., T.L. Neal, Z-V Palmrose, and S. Scholz. 2011. CEO involvement in selecting board

members, audit committee effectiveness, and restatements. Contemporary Accounting

Research 28: 396-430.

Chan, L., K.C. Chen, T.Y. Chen, and Y.X. Yu. 2011. The effects of firm-initiated clawback

provisions on earnings quality and auditor behavior. Working Paper, Hong Kong University

of Science and Technology. 2011 Journal of Accounting and Economics Conference.

Chan, L., K.C. Chen, T.Y. Chen, and Y.X. Yu. 2012. Substitution between real and accrual-based

earnings management after voluntary adoption of compensation clawback provisions.

Working Paper, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. 2012 Journal of

Accounting and Economics Conference.

Chen, K. and J. Zhou. 2007. Audit committee, board characteristics, and auditor switch decisions

by Andersen's clients. Contemporary Accounting Research 24 (7): 1085–117.

Cohen, J., G. Krishnamoorthy, and A. Wright. 2010. Corporate governance in the

post-Sarbanes-Oxley era: Auditors’ experiences. Contemporary Accounting Research 27 (3):

751–786.

Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO). 1992. Internal

control integrated framework. COSO, New York, NY.

Core, J. E., R. W. Holthausen, and D. F. Larcker. 1999. Corporate governance, chief executive

officer compensation, and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics 51 (3):

371–406.

Cullinan, C.P., H. Du, and W. Jiang. 2010. Is compensating audit committee members with stock

options associated with the likelihood of internal control weaknesses? International

Journal of Auditing 14: 256-273.

Dalton, D.R., C.M. Daily, T. Certo, and R. Roengpitya. 2003. Meta-analyses of financial

performance and equity: Fusion or confusion? Academy of Management Journal 46 (1):

13-26.

Dao, M., K. Raghunandan, and D.V. Rama. 2012. Shareholder Voting on Auditor Selection, Audit

Fees, and Audit Quality. The Accounting Review 87 (1): 149-171.

Dechow, P.M., R.G. Sloan, and A. Sweeney. 1996. Causes and consequences of earnings

manipulation: An analysis of firms subject to enforcement actions by the SEC.

Contemporary Accounting Research 13 (2): 1–36.

24

Accounting Review 66 (3): 643–55.

DeFond, M. L., R. N. Hann, and X. Hu. 2005. Does the market value financial expertise on audit

committees of boards of directors? Journal of Accounting Research 43 (2): 153–93.

Dehaan, E., F. Hodge, and T. Shevlin. 2012. Does voluntary adoption of a clawback provision

improve financial reporting quality? Contemporary Accounting Research (forthcoming).

Desai, H., S. Krishnamurthy, and K. Venkataraman. 2006. Do short sellers target firms with poor

earnings quality? Evidence from earnings restatements. Review of Accounting Studies 11 (1):

71–90.

DeZoort, F. T., D. R. Hermanson, D. Archambeault, and S. Reed. 2002. Audit committee

effectiveness: A synthesis of the empirical audit committee literature. Journal of Accounting

Literature 21: 38–75.

Dhaliwal, D. V. Naiker, and F. Navissi. 2010. The association between accruals quality and the

characteristics of accounting experts and mix of expertise on audit committees.

Contemporary Accounting Research 27(3): 787-827.

Eisenberg, T., S. Sundgren, and M. T. Wells. 1998. Larger board size and decreasing firm value in

small firms. Journal of Financial Economics 48 (1): 35–54.

Efendi, J., Srivastava, A., & Swanson, E. P. 2007. Why do corporate managers misstate financial

statements? The role of option compensation and other factors. Journal of Financial

Economics 85 (3): 667–708.

Engel, E., R. Hayes, and X. Wang. 2010. Audit committee compensation and the demand for

monitoring of the financial reporting process. Journal of Accounting & Economics 49 (1/2):

136–54.

Ettredge, M.L., S. Scholz, K. Smith, and L. Sun. 2010. How do restatements begin? Evidence of

earnings management preceding restated financial reports. Journal of Business Finance &

Accounting 37 (3/4): 332–355.

Fama, E. F., and D. R. French. 1997. Industry costs of equity. Journal of Financial Economics 43

(February): 153-193.

Fan, J.P.H. and T.J. Wong. 2005. Do external auditors perform a corporate governance role in

emerging markets? Evidence from East Asia. Journal of Accounting Research 43 (March):

35-72

Farber, D. B., 2005. Restoring trust after fraud: does corporate governance matter? The Accounting

Review 80 (2): 539–561.

Financial Reporting Council. 2003. Combined Code on Corporate Governance. London, U.K.:

FRC. Available at http://www.frc.org.uk/documents/pdf/combinedcodefinal.pdf.

Finkelstein, S. Power in top management teams: Dimensions, measurement, and validation.

Academy of Management Journal 35 (1992): 505-538.

General Accounting Office, 2002. Financial statement restatements: Trends, market impacts,

regulatory responses, and remaining challenges, GAO-03-138.

General Accounting Office, 2006. Restated Financial Statements: Agencies' Management and

Auditor Disclosures of Causes and Effects and Timely Communication to Users,

GAO-07-91.

Goh, B. 2009. Audit committees, boards of directors, and remediation of material weaknesses in

internal control. Contemporary Accounting Research 26 (2): 549–79.

25