Yu, C.-S. and Tao, Y.-H. , Enterprise e-marketplace adoption: from the perspectives of technology acceptance model, network externalities, and transition costs, 資訊管理學報 ,第十四卷,第四期,2007,231-265 (TSSCI)

Firm-level technology adoption:

Learning from Enterprises e-marketplace adoption

企業的科技採用:學習自企業的電子市集採用

Chian-Son Yu

Institute of Information Technology and Management, Shih Chien University 余強生

實踐大學資訊科技與管理學(系)所 Yu-Hui Tao

Department of Information Management, National University of Kaohsiung 陶幼慧

國立高雄大學資訊管理學系

Corresponding author: Chian-Son Yu

Professor, Institute of Information Technology and Management Shih Chien University

#70, DaZhi Street, Taipei 10497, Taiwan Email:csyu@mail.usc.edu.tw Tel: 886-2-25381111 ext. 8921, 8011 Fax: 886-2-25333143 聯絡作者: 余強生 實踐大學資訊管理學系教授 台北市大直街 70 號 Email:csyu@mail.usc.edu.tw Tel: 886-2-25381111 ext. 8921, 8011 Fax: 886-2-25333143

Firm-level technology adoption:

Learning from Enterprises e-marketplace adoption

ABSTRACT

Motivated by understanding individual-level technology adoption has been extensively investigated during last twenty years while understanding technology adoption at the firm level has not been studied and ascertained, this study thus attempts to employs technology acceptance model (TAM) and diffusion of innovation (DOI) as a theoretic foundation to probe whether TAM can effectively predict enterprise e-marketplace adoption at pre-decision and in-decision stages. Besides, 有 鑑於 extant theory-based e-marketplace literature heavily lies in using economic theory’s transaction cost while 缺乏 and 忽略了 offer empirical evidence to verify 經濟學理論中 other economic consideration 是否也會對 enterprises e-marketplace adoption 產生影響. Thereby, by conducting an empirical study, this investigation examines whether network externalities and transition cost will significantly alter or reverse enterprises original e-marketplaces adoption choice at the post-decision stage. Business and theoretical implications concluded from the empirical results might be generalized to other organization-level technology adoption contexts.

Keywords: E-marketplace, Technology Acceptance Model, Network Externality,

1. Introduction

Extant research has demonstrated that the end-user technology adoption can be effectively predicted by technology acceptance model (TAM), and much literature has supported that bearing TAM in the R&D and marketing contexts is quite useful for launching technology-based new product/service to end-consumers. However, the underlying TAM at the firm level has not been studied and ascertained. Since enterprises every year allocate large portion of budget on procuring information technology/system (IT/IS) based products/services (隨著 e-century, e-business 的發 展,此趨勢將更為明顯), thereby understanding firm-level technology adoption is just as important as individual-level technology adoption. However, 相 對 於 understanding individual-level technology adoption has been extensively investigated over last two decades, literature on understanding firm-level technology adoption is relative scant. Motivated by this phenomenon, this study attempts to employ TAM and diffusion of innovation (DOI) to construct a theoretic foundation to examine whether TAM effectively foresee enterprise e-marketplace adoption at pre- and during-decision stages. Since e-marketplaces is one of IT/IS based products/services, some business and theoretical implications concluded from the empirical results might be generalized to other organization-level technology adoption contexts.

Additionally, with e-commerce unprecedented rapid developments that provide enterprises an opportunity to reach out to global markets and conduct business through Internet links, many enterprises have shifted bricks-and-mortar trading activities to Internet-based cybernetic trade platforms called e-marketplaces that enable automated transactions and collaboration between buyers and sellers. Although e-marketplaces have received intensive attention from both the academics and the practitioners with a leaping number of studies in recent years, prevailing theory-based e-marketplace literature lies in using economic theory to explore enterprises e-marketplace adoption (Bakos, 1991, 1997; Strader and Shaw, 1999; Bensimane et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2006). Among those works based on economy theory to exploring enterprises e-marketplace adoption, dominant of those works 經常侷限於 只 offering empirical evidence to support/test 經濟學理論中的 transaction cost including search costs and coordination costs (Benslimane et al., 2005), 而忽略了 to explore/verify 經 濟 學 理 論 中 other economic consideration such as network externalities and transition costs. Although some articles (Strader and Shaw, 1999; Grover and Ramanlal, 2000; Jiang, 2002) 留意到 that transaction risk, price, and taxes, marginal costs, and market costs1 also impacts firms to adopt or not adopt e-marketplaces, among those few research noticing other economic consideration 多 只有理論上的討論缺乏提供 empirical evidence to support/examine whether these economic consideration significantly change or reverse firm original e-marketplace adoption choice. Motivated by narrowing/fulfilling this gap, this work conducts an empirical study to testing whether enterprises e-marketplaces adoption will be influenced by network externalities and transition costs at the post-decision stage.

The rest of this work is organized below. Section 2 paves a theoretical background, and hypothesis developments are then followed in the section 3. Section

1

Market costs can take the form of fixed monthly market access fees, fixed fees per transaction, or variable fees based on the value of the transaction (Strader and Shaw, 1999).

4 briefly describes the questionnaire design and data collection, while hypothesis test and statistical analysis are discussed in Section 5. Some business and theoretical implications concluded from the empirical study and the research limitation and concluding remarks are given in Sections 6 and 7, respectively.

2. Theoretical Background

Owing to that individual behavior is traceable and explainable by social psychology theories, during the past two decades numerous literature induces social psychology theories (i.e., theory of reasoned action) to construct a research structure (i.e., TAM) to investigate what (or how to) influences individual attitudes and decision in many IT/IS adoption. Since, in practice, the whole organization behavior is just like behavior acting by a collective group instead of single person, organizational behavior 也一定有 certain 軌跡可供觀察與研究, which originates organizational behavior discipline 的發展 (Lu, 1993).

組織行為是一種重要的組織現象,主要是以成員個人、群體、整個組織及其

外部環境的相互作用所形成的行為作研究對象。From the micro viewpoint,

organization behavior mainly comprises individual behavior within an organization, inter-person and inter-group behavior in an organization, the behavior between individual and organization, and the whole organization behavior. From the macro

viewpoint, 組織行為可簡單地分為個體行為和群體行為。Many studies found that

群體行為的 decision process 比個體行為的 decision process 更為 tedious and inefficient, organization decision also inherits rational and irrational components of individual decision, and the collective decision within an organization very often is not the best but the suitable or most promising to the entire participants of organization decision.

由於 numerous studies on understanding individual technology adoption exits while research on understanding an entire firm technology adoption is relatively scarce, thereby this work 首先 extends DOI and TAM to construct a three-stage research framework of investigating enterprises e-marketplace adoption. Notably, the economic theory in terms of network externalities and transition costs is also included in the research structure due to the importance and imperative about offering empirical evidence to test whether (except for transaction cost) other economic consideration also considerably affect or reverse enterprises e-marketplace adoption choices. The empirical results might be generalized to other firm-level technology adoption.

In contrast to that prevailing DOI/TAM-based literature generally takes individual-level users as a survey unit, this study takes collective organizations (firm-level users) as an analysis unit to exploring what influences an enterprise e-marketplace adoption at the pre- and in-decision stages, and whether network externalities and transition costs impact enterprises e-marketplaces adoption at the post-decision stage. Accordingly, hereafter the term “end-consumer”used in this work is deemed a/an firm, enterprise, or organization. As a result, this work may pave the ground for a better understanding of how a general technology is adopted by business firms instead of individual users, and offer some valuable clues to those who like to effectively selling industry products to firms.

2.1 DOI

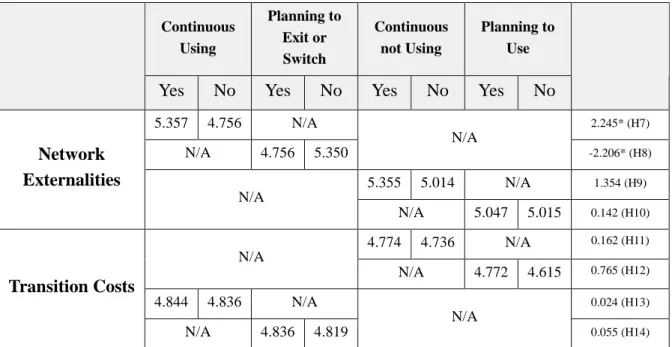

DOI, devised by Rogers in 1962 (Rogers, 2003), is used as a process-oriented viewpoint to explain how an innovation could be accepted and disseminated within end-consumers. DOI contends that the adoption or rejection of an innovation begins when the end-consumer becomes aware of the innovation, and the transformation of messages regarding an innovation through certain channels over time among end-consumers is called a diffusion process. Meanwhile, time is used to trace the sequential flow of an innovation through many end-consumers who engage in consideration decision about the adoption of an innovation. Innovation is defined as an idea, practice, product, service, or object perceived as new by an end-consumer. Accordingly, the model of firm-level DOI process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Insert Fig. 1 here. 2.2 TAM

TAM, presented by Davis in 1986 (Davis, 1986, 1989), is used to effectively explain people’s computer adoption by two simple but significant constructs of usefulness and ease-of-use. Over the past two decades, gigantic works have extended TAM to predict people’s attitudes and use behavior for legion IT/IS-based product/service adoption. In firm-level TAM, usefulness is defined as how many benefits can be obtained by using the product/service, which is subjectively evaluated by end-consumers. Ease-of-use is defined as the degree the end-consumer can effortless use the product/service. For a firm, the effort could be a budget investment, employer training/learning time, maintenance cost, and so forth. Accordingly, the concept of firm-level TAM can be pictured as follows:

Insert Fig. 2 here. 2.3 Network Externality and Transition Cost

Numerous studies have exploited economic theory to investigating e-marketplace adoption (Dai and Kauffman, 2004), and widely attributed the emergency and development of e-marketplace to economic advantages such as e-marketplaces can reduce searching costs that buyers incur when sourcing suitable products, comparing prices and product data, and marketing cost that sellers incur when attempting to attract prospective customers and promote products. However, except for the transaction cost such as search costs and marketing costs, the economies of scale and scope, network effects, switching costs, and path dependency may be also associated with the growth of e-marketplace (Ratnasingam et al., 2005; Zhu et al., 2006). Nevertheless, since dominant economic-theory-based e-marketplace literature frequently 侷限於只使用經濟學理論中的 transaction cost 而忽略了經濟學理論中 other economic consideration, this work aims to take network externalities and switching costs into the research structure to explore whether initial enterprises e-marketplace adoption choice will be altered by network externalities and switching costs at the post-decision stage. In fact, using network externality or transition cost to explore e-marketplace adoption is a not new idea (Bakos, 1991; Shapiro and Varian, 1999; Zhu et al., 2006), but extant literature is still few and lacks of giving empirical evidence.

Drawn upon the economic perspective which views the adoption decision in terms of benefits and costs, network externalities (or called network effects) is

deemed a key factor influencing the adoption of e-marketplaces (Bakos, 1991; Shapiro and Varian, 1999; Zhu et al., 2006). In a network market formed from products (or services) with network externalities, the value/effectiveness of the product (or service) always rises as long as new consumers are added to the market. In other words, each end-consumer is considered to have a network externality on the behaviors of other end-consumers as long as the actions of end-consumers can directly impact the economic utility of other end-consumers (Allen, 1988; Brynjolfsson and Kemerer, 1996; Au and Kauffman, 2001; Lee et al., 2003).

Drawn upon the path dependence perspective which views the adoption decision 存有先佔先贏的現象, large literature on technology adoption (Fabiani et al., 2005) has illustrated that, for a variety of reasons, a new technology (even superior to old one) requires time before taking most of the market shares. Accordingly, old technologies (even inferior to new one) might take competitive advantages if they 先 佔據市場 and 存有 switching cost barriers between old technologies and new technologies. Given an environment where IT/IS evolves stochastically over time, potential users choosing among IT/IS-based products/services must consider whether the available product/service today will not be an obsolete one in the future. This is particularly important when the choice is largely irreversible. Hence, in practice, a transition cost occurs as long as users migrate current product (service) to a new product (service).

2.4 The concepturized research structure

Building the above discussion, this work employs DOI, TAM, network externalities and transition costs to investigating enterprises e-marketplace adoption in a three-stage model of pre-decision, in-decision, and post-decision. The goal aims to verify whether TAM effectively explains enterprises e-marketplace adoption at the pre- and in-decision stages, and whether network externalities and transition costs effectively 左 右 enterprises previous e-marketplace adoption choice at the post-decision stage. Accordingly, the research structure can be concepturized as the follows.

Insert Fig. 3 here.

3. Hypothesis Development

Just as the adoption of B2C e-commerce, participants adopt B2B e-marketplaces only when they can benefit from B2B e-marketplaces, usually saving or making money. Therefore, to a business, usefulness regarding the e-marketplace adoption is to analyze how many benefits can be brought and/or how many costs can be reduced by using e-marketplaces, while ease-of-use means the degree of minimal effort such as time, capital, training, and so on for a firm required to invest. Therefore, grounded in TAM, following four hypotheses are posited:

H1: Usefulness significantly influences a firm’s top management willingness to adopt an e-marketplace.

H2: Ease-of-use significantly influences a firm’s top management willingness to adopt an e-marketplace.

H3: Ease-of-use significantly influences Usefulness.

influences a firm’s actual decision in e-marketplace adoption.

Although TAM is quit simple and employ only two constructs- usefulness and ease-of-use instead of many constructs to reasonably explain individual computer adoption, many researches also suggested that for specific IT/IS based product/service to including additional variables into the original TAM is necessary for enhancing its applicability and explanative ability (Davis, 1993; Hu et al., 1999; Legris et al., 2003; Wu and Wang, 2005). Therefore, extra but crucial constructs drawn from relevant literature are analyzed next.

Since e-marketplaces may be regarded as evolved from electronic data interchange (EDI) systems that is incurred from the needs of e-procurement (Angeles, 2000), and fully supported by IT, IS, and communication technologies (Guilherme and Aisbett, 2003), those variables influencing the e-marketplace adoption may refer to literature on the adoption of e-procurement (Aisbett et al., 2005), IT (Davis, 1989; Karahanna et al., 1999), IS (O' Callaghan et al., 1992; Thong, 1999; Gefen and Straub, 2000), EDI (Premkumar et al., 1994; Angeles, 2000), e-commerce (Poon and Swatman, 1999; Kendall et al., 2001; Travica, 2002), telecommunication (Grover and Goslar, 1993; Pollard, 2003), and Internet related technologies (Slade and Van Akkeren, 2002; King and Gribbins, 2003).

In Grover and Goslar study (1993), they identified that firm scale will influence firm decisions regarding new technology adoption, the extent of standardization and documentation in company workflow also influences the likelihood of new technology adoption, and companies that have well established IS being more willing or ready to adopt new technologies. By surveying of 166 businesses and examining company decisions to adopt new IT/IS, Thong et al. (1995) and Thong (1999) discovered that (1) larger companies are more likely to adopt new IT/IS; (2) companies that depend on complete, rapid, and reliable information exchange are likely to adopt new IT/IS; (3) the greater the compatibility between the new IT/IS and existing company workflow and systems, the more likely the adoption of new IT/IS; and (4) If an enterprise decision-making team is dispersed globally rather than regionally, then the company is more likely to adopt new technologies to facilitate effective and efficient information flow. Accordingly, these findings demonstrate that inside characteristics of an enterprise may be treated as an antecedent of influencing firm e-marketplace adoption.

Consequently, the following hypothesis is posited:

H5: The inside characteristics of a firm (IC-of-Firm) significantly influence firm e-marketplace adoption.

By researching 1242 agencies for the influences on decision regarding whether or not to adopt EDI, O’Callaghan et al. (1992) identified that adoption by important customers within the supply chain or by other companies in the same industry and governmental or regulatory incentives are key external influences on EDI adoption decision. Besides, Grover and Goslar (1993) surveyed 154 firms and found that stability of enterprise competitive environment is an impact on firm intention to adopt or not adopt new technologies. If the competitive environment is complicated and volatile, then firms are generally aware of innovation and new technology adoption to remain competitive. Many studies also pointed to that business-to-business (B2B)

e-marketplace has evidently played a central role in facilitating e-supply chain development (Singh et al., 2005; Lu and Antony, 2003) and deemed as one of the most significant industry structure changes since the Industrial Revolution (Rayport and Sviokla, 1994; Ratnasingam et al., 2005). To sum up, these findings lead that outside competitive environment of a company may become an important antecedent of influencing firm e-marketplace adoption.

Accordingly, the following hypothesis is posited:

H6: The outside competitive environment of a firm (OCE-of-Firm) significantly influences firm e-marketplace adoption.

According to DOI that divides the diffusion process into three stages of pre-decision, in-decision, and post-decision as depicted in Fig. 1, 對於 an innovation 的 看 法 is influenced by characteristics of end-consumers (Rogers, 2003), information about the innovation received by end-consumers at the pre-decision stage thus will shape end-consumer favorable or unfavorable decision regarding the adoption of an innovation. The in-decision stage takes place when an end-consumer engages in activities that lead to the choice between adopting and rejecting an innovation. The post-decision stage occurs immediately after end-consumers make a choice about putting an innovation to use or not. During the post-decision stage, end-consumers seek reinforcement for their previous decision, and may reverse the choice if exposed to dissonance messages regarding the innovation. That is, non-adopters may either continuously reject using the innovation or choose to adopt the innovation. Non-adopters adopt an innovation if they are motivated to do so after securing further information or evidence that influences their original decision of not adopting the innovation. Conversely, adopters may continuously use the innovation or alternatively reject using it at the post-decision stage.

The analysis of network market can date back to the 1970s (Squire 1973, Rohlfs 1974). Literature contended that network externalities are an economic scale phenomenon that depicts the utility derived by the end-consumer from the product/ service and the rises/falls that occur with a change in the number of end-consumers using the product/service, while transition costs are an economic lock phenomenon that depicts the money invested by the end-consumer for using the product/service will be sunk when discarding it. E-marketplaces seem a typical network market just like other examples of telephone, telecommunication, television, newspaper, and packaged computer software, as well as web-based services such as electronic mail systems, bulletin board systems, online games and instant message service (e.g., ICQ, MSN). Therefore, network externalities are examined to verify whether firm e-marketplace adoption choice will be reversed or altered at the post-decision stage. Besides, numerous studies (Clemons and Kleindorfer, 1992; Choi, 1994; Wang and Seidmann, 1995; Economides, 1996; Choi and Thum, 1998; Hoppe, 2000; Kauffman et al., 2000; Au and Kauffman, 2001; Gallaugher and Wang, 2002; Asvanund et al., 2004) during the last 30+ years have showed that an inferior technological product may not be replaced by superior alternatives as long as transition costs plays a crucial role in its adoption and use. The market share of 2.5G and 3G cell-phone systems provide a good example of this phenomenon. Hence, transition costs are probed to see could the original firm e-marketplace adoption choice be changed or reversed at the post-decision stage.

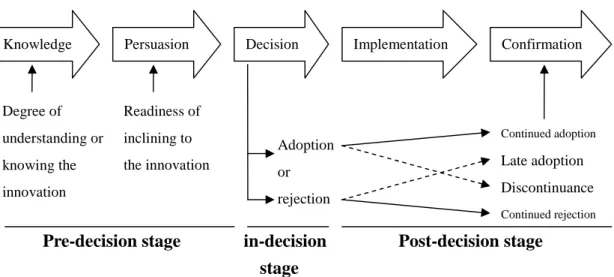

Building the above discussion, this work hypothesizes network externalities and transition costs as reinforcement variables that influencing end-consumers to reconfirm their previous decision or reverse their original decision. As a result, the following hypotheses are posited:

H7: Network externalities significantly influence adopting firms to continue using the current e-marketplace.

H8: Network externalities significantly influence adopting firms to switch or exit the current e-marketplaces.

H9: Network externalities significantly influence non-adopting firms to plan to use an e-marketplace.

H10: Network externalities significantly influence non-adopting firms to continue not to use any e-marketplace.

H11: Transition costs significantly influence adopting firms to continue using the current e-marketplace.

H12: Transition costs significantly influence adopting firms to switch or exit the current e-marketplaces.

H13: Transition costs significantly influence non-adopting firms to plan to use an e-marketplace.

H14: Transition costs significantly influence non-adopting firms to continue not use any e-marketplace.

Based on the above hypothesis development, the research structure is pictured as follows:

Take in Fig. 4.

4. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

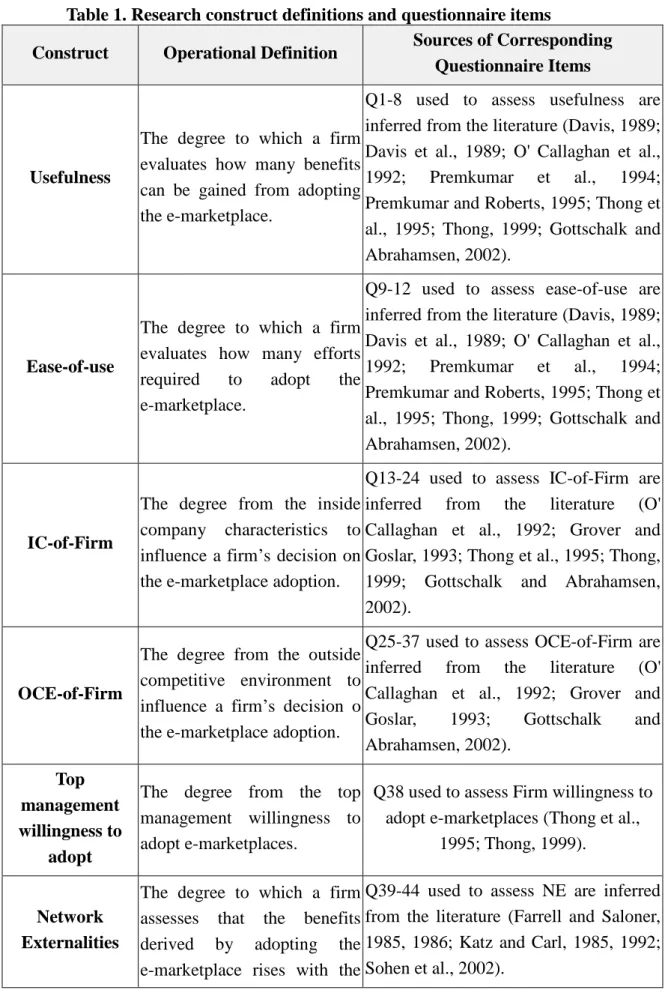

The survey questionnaire was designed through the following two steps: (1) items to measure each corresponding construct were selected from the literature and reworded to fit the enterprises e-marketplace adoption; (2) a pretest conducted on scholars and participants of e-marketplaces was used to refine the survey questions. Constructs of usefulness, ease-of-use, IC-of-Firm, OCE-of-Firm, network externalities, and transition costs displayed in Fig. 1 are defined in Table 1, which also lists corresponding questionnaire items used to assess each construct and drawn from the related literature. The questionnaire comprises two sections. The first section contains 51 questions that are assessed on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), and collects the assessment of six constructs and the willingness of adoption by responded companies. The second section, containing 12 questions, gathers basic data on each respondent company and aims to realize the intention of each respondent firm to adopting an e-marketplace, whether the responded firm has joined an e-marketplace, that type of e-marketplaces the respondent firms have joined, and whether those adopting-firms plan to continue using, switch, or stop using e-marketplaces, as well as whether those non-adopting-firms plan to adopt or continue not using e-marketplaces.

Take in Table 1.

Like dominant organizational-level survey studies (Grewal et al., 2001; Lucchetti and Sterlacchini, 2004; Zhu et al., 2006), the key informant method was used in this

study. To validate the respondents, a questionnaire was sent to 1,500 large Taiwanese firms with attention to the procurement or sales manager in charge of e-marketplace adoption. Also, concise statements at the beginning of the questionnaire described the purpose of the research, and the addressee or other managers who are familiar with e-marketplace operation was invited to participate in this survey study. To encourage respondents filling out and returning the questionnaires with complete data, we likewise sent out two follow-up mails and increased the return rate by giving the first 100 respondents a bottle of a famous local fruit vinegar as a gift.

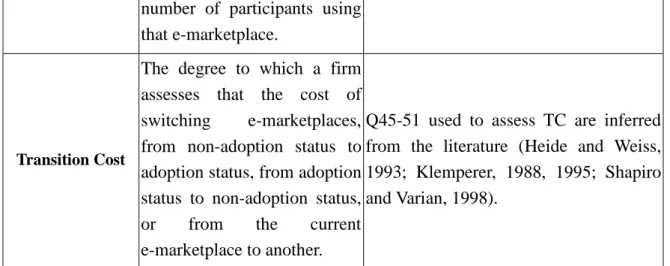

Among 295 responses, 202 were considered valid, which corresponded to 13.5 percent of the valid response rate. Compared with survey return rates ranging from 16.5% to 11.5% in Taiwan’s empirical industry studies within last five years (Yu, 2006), a 13.5 percent valid response rate generated from an overall 19.7 percent response rate was compatible with recent surveys of Taiwanese firms. Table 2 briefly profiles these 202 firms as follows: 94 responses have used at least one e-marketplace; the scale of respondent firms from the average employee size, capital, and revenue meets the expectation of large firms by well over Taiwan’s standard of small and medium enterprises; they are very profitable based on the over 300 percent average ratio of revenue over capital; the percentiles of industry type also suitably reflects current industry distribution of electronic, information, optics, machinery, metal, chemistry, and semiconductor industries in Taiwan. Moreover, the average annual membership fee of NT$ 42,194 (roughly US$1,310) is not high for large firms. Table 2 also reveals that over 80% of adopting-firms reported that revenue generated by e-marketplaces comprised less than 30% of their total revenue, but only one-third of firms said that the benefits brought by e-marketplaces were less than expected. This phenomenon may imply that Taiwanese firms consider e-marketplaces as just one of their trading channels at that time of conducting this survey.

Take in Table 2.

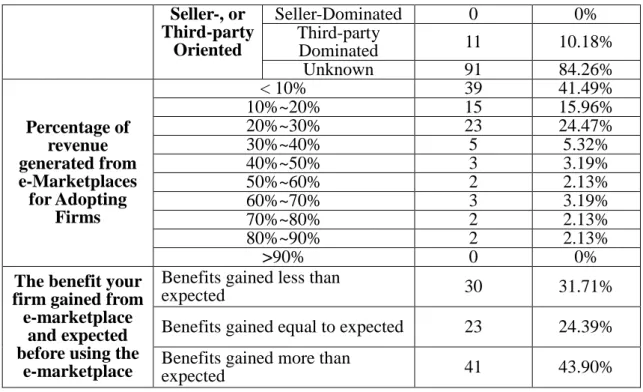

5. Reliability, Validity, and Hypotheses Test

Since the survey questions are constructed based on empirical studies of the literature, the content validity was verified. The construct validity was examined by factor analysis, while the consistency reliability was measured using the Cronbach Alphas. Therefore, following the factor analysis through the SPSS 12.0 software, six constructs and nine sub-constructs are identified as shown in Table 3. Based on the judge criterion, questions 4, 12, and 44 were discarded. The judge criterion is for each sorted question pertaining to each factor the corresponding intra-factor loading must exceed 0.6 and the difference between the corresponding intra-factor loading and each other-factor loading must over 0.3. Notably, each sub-construct name is given by best reflecting the context of the corresponding items. The computed Cronbach alpha coefficients for all dimensions exceed 0.78, as shown in the last column of Table 3, indicating that the content consistency between the questions relating to each of the constructs is very high. Additionally, inter-item correlation matrixes under each construct have been examined and all are very significant (p < 0.01). As a result, the above statistical analysis demonstrates that the survey has good predictive, convergent, and discriminant properties (Davis et al., 1989; Adams et al., 1992).

Take in Table 3.

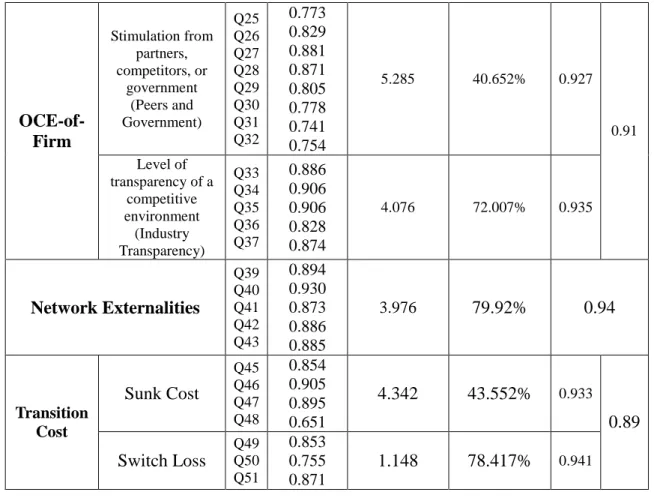

From the research structure in Fig. 4, it looks reasonable to apply the structural equation model with a software like LISREL for hypothesis testing. However, there is a lack of model-based literature investigating the antecedents of organizational participation in B2B e-marketplaces. In particular, this work is the first attempt to integrate TAM and DOI as a research ground to investigate a firm-level technology adoption; thus, we approach the data analysis through factor analysis for the construct validity and regression analysis for the hypothesis testing. Notably, Davis, who first presented TAM in 1986, has long used the regression method to examine the hypotheses grounded from TAM, extended TAM, or TAM 2 (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989; Davis, 1993; Venkatesh and Davis, 1996 and 2000). This might be attributed to the finding that the regression technique not only can use a limited number of predictor variables to clarify the tendency of the response variable in a systematic fashion (Neter et al., 1999), but it can also quantify the relationship between dependent and independent variables and the explanatory power of the entire model. As a result, H1-H3 and H5-6 were tested via linear regression model. Since “firm decision on the e-marketplace adoption”, “adopting firms continue to use the current e-marketplaces”, “adopting firms switch or exit the current e-marketplaces”, “non-adopting firms plan to use e-marketplaces”and “non-adopting firms continue not use any e-marketplaces”are binary variables, H4 and H7-H14 were verified using t-value test.

Take in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4 demonstrates that the proposed extended TAM model explained 86.3% of the variance observed in firms’ top management willingness to adopt e-marketplaces, and ease-of-use accounted for 21.8% of the variance in usefulness. After deducting inside enterprises characteristics and outside competitive environment from the presented TAM model, this study found that even using only two constructs -usefulness and ease-of-use – can predict 69.1% of the variance in firms’ top management willingness to adopt e-marketplaces. Accordingly, Hypotheses 1-3 and 5-6 are accepted. In contrast to prevailing individual-level TAM studies that the variance explained by usefulness and ease-of-use in people’willingness to adopt IT/IS is usually less than 40% (Hung et al., 2006), the findings from this empirical study display that TAM can explain firm-level technology adoption more than individual-level technology adoption. A plausible explanation might be that corporate decisions are made by a group that deliberates its needs during collective meetings, while single person may made a decision in a more emotion incline and shorter process/time. Since the process of forming the whole corporate decision is much longer and less subjective than that of forming an individual user decision, usefulness (how many benefits can be brought by adopting the new product/service) and ease-of-use (how much effort are required to invest when adopting the new product/service) has become more fundamental construct to influencing firm-level decision than individual-level decision regarding the adoption of new product/service.

The figures in Table 5 reveal that only hypotheses 4 and 7-8 were accepted, while hypotheses 9-14 were rejected. That means only adopting-firms will be influenced by network externalities when intending to stay in, switch to another one, or exit from current e-marketplaces. For non-adopting firms, neither network

externalities nor transition costs will impact their decision in continuous not using e-marketplaces or planning to use. For transition costs, this kind of economic factor do not play an influential role in both adopting-firms and non-adopting-firms decision regarding influencing their original decisions. Regarding Hypothesis 4, a logical regression analysis is further conducted as listed in Table 6. Both Tables 5 and 6 confirmed that firms’ top management willingness to adopt e-marketplaces significantly affects their decision, which is consistent to individual-level TAM-baaed literature. However, notably, the overall correct classification rate is only 62.1% as displayed in Table 6 much lower than the influence from individual attitudes in terms of willingness to individual adoption behavior. Which may be because collective decision process 會由多人從正反面的優缺點去對 a new product/service 作探討 than single person did. Therefore, 從 有 意 願 去 採 用 到 實 際 採 用 的 這 段 距 離 (variance) in firm-level technology adoption is bigger than that in individual-level technology adoption. Besides, as we know, the statistical 嚴謹度 of the structural equation model is more rigorous than that of the regression model and t-value test, which explains why Davis always first used the regression model to examine the presented TAM or its extensions/variations. After that, other researchers use structural equation model to do more empirical tests examining the robustness of Davis’s proposed TAM models. Therefore, more empirical studies to support/examine the presented research structure are definitely required.

6. Implications and Discussions

The technology adoption based on TAM or DOI has been extensively studied, but pertinent literature generally takes end-users (individual-level users) as a survey unit. In contrast, this study takes collective organizations (firm-level users) as an analysis unit and explores whether TAM prominently influences an enterprise e-marketplace adoption at the pre- and in-decision stages, and whether network externalities and transition costs will impact a firm e-marketplace adoption at the post-decision stage. Consequently, this work may pave the ground for a better understanding of how a general technology is adopted by business firms instead of individual users, and offer some valuable clues to those who like to effectively selling industry products to firms. As a result, four business and two theoretical implications concluded from the empirical results are addressed as following.

The first business implication is since 69.1% of the variance in firms’ top management willingness to adopt e-marketplaces can be explained by usefulness and ease-of-use, bearing TAM in the R&D and marketing stages for selling technology-based new product/service to firm-level end-users is also quite useful. Besides, after deducting usefulness and ease-of-use from the presented structure shown in Fig. 4, Table 4 reveals that inside enterprises characteristics and outside competitive environment can jointly predict 25.1% of the variance in firms’ top management willingness to adopt e-marketplaces, meanwhile outside competitive environment holds more powerful influence than inside enterprises characteristics according to Table 4. That means those companies facing unstable or extensive competitive business circumstance should be put the first priority prospective customers when launching a new product/service, while those companies having higher readiness regarding their inside characteristics could be deemed the second priority target consumers.

Table 4 also indicates that, after ease-of-use, usefulness, outside competitive environment, and inside enterprises characteristics jointly incurred firms’top management willingness (such as realizing the adoption of e-marketplace may benefit their business), some variance still exits 從 willingness to adopt 到 actual adoption. Based on this fact, the second business implication is to find out which firms’top management have higher willingness, and actively and concentrate on marketing products/services to those firms. E-marketplace management may invite firms’top management with high-willingness to attend 產品說明會 或 visit those firms’top management and persuade them to 試用 e-marketplaces. Of course, before taking any marketing action/campaign, conducting an industry survey knowing firms’top management willingness is first and foremost step.

Based on the fact that network externalities only affect an adopting firm’s decision to remain in a current e-marketplace and exit or switch to another one, e-marketplace management should notice the network externalities 對 current customers 的衝擊. That is, 定期 (i.e., 每週) issue 會訊給現有會員 and telling them 本電子市集本週又提供了那些新的服務,協助那些公司完成多少筆交易,本 週又有那些會員加入, 就像各大學校訊的宣傳或各大報宣稱我們是第一大報 or 宣稱在某個 niche sector (i.e.,高收入的菁英經理人)我們訂報率第一. Following this strategic 思維, an e-marketplace may claim that it has the largest 顧客群 among top 2000 firms, a certain e-marketplace may claim that last month 40% of Taiwanese export trade is conducted via this e-marketplace, or the alike. Accordingly, the third business implication is that 對於現有顧客要定期寄予文宣、透露政績、進 行國威宣傳 would enhance their confidence and raise 續用率.

Unlike EDI built on closed network without a standard exchange format, the empirical evidence reveals that participating in an e-marketplace is not an irreversible choice and does not incur a technology-switch barrier since e-marketplaces are built on open Internet technology using the compatible format. Consequently, the fourth business implication is that transition cost does not play a critical role in either adopting or non-adopting firm decision toward adopting/switching e-marketplaces. This phenomenon can be attributed to two reasons. First, participating in an e-marketplace is not an irreversible choice and does not incur a lock-in technology barrier. Restated, early commitment to an e-marketplace does not deprive a firm of subsequent opportunities to join other e-marketplaces. Second, provided that sufficient benefits can be gained by joining an e-marketplace, the transition cost is considered trivial for enterprises. These findings are useful not only for e-marketplace managers, but also for other IT/IS-based product/service managers, particularly in developing a business model for effectively retaining existing customers and attracting new ones.

Many academics and practitioners have employed the TAM or its extended model to explain people technology adoption, while TAM has not been studied and ascertained in organization-level technology adoption. Since the technology adoption not only occurs in a single person decision but more frequently occurs in a team or firm-level decision, this investigation might pave a theoretical background for a better understanding of how a general technology is adopted by business firms instead of end-users. Therefore, concluding from the empirical results, the first theoretical implication is that the extended TAM not only effectively predict firm-level

e-marketplace decision, but also generate higher 解 釋 度 in firm-level than individual-level technology adoption. The reason may be attributed to collective decision 比 single person decision 更具理性, 而 TAM is adapted from theory of reasoned action. Since an e-marketplace is one of IT, IS, or Web based product/service, its finding might be generalized as a general organization-level technology adoption theoretical basis.

By surveying 94 firms that had adopted e-marketplaces and 108 firms that had not yet adopted e-marketplaces, this empirical study has identified that network externality only partially clarify enterprises e-marketplace adoption at the post-decision stage, while the transition cost is ineffective in explaining firm technology adoption at the post-stage. This phenomenon demonstrates that except for transaction costs other economic consideration may not be a crucial factor for firm technology adoption at the post-decision stage. That is, what influences firm-level technology decision heavily relies on the fundamental benefits such as how many benefits in terms of increased trade amount/opportunities, decreased operation cost, and so forth. Consequently, the second theoretical implication is network externalities (such as how many firms have used the product/service) will impact adopting-firms’previous choice, while non-adopting firms’original decision will not be impacted by transaction costs (such as how many lost incurred when switching to another product/service). This empirical evidence may be potentially applied to explain other network market’s products/services.

7. Conclusions and Future Research

TAM is adapted from social psychological theory and has been widely used to predict a single user’s technology acceptance behavior over two decades. Since much literature has supported TAM in individual technology adoption while the underlying TAM at the firm level has not been studied and ascertained, this work has presented a three-stage research structure to examine whether TAM can effectively forecast enterprise e-marketplace adoption at the pre- and in-decision stages. By empirical surveying 202 responding firms, this work verifies that TAM effectively forecast enterprise e-marketplace adoption, and even better than individual technology adoption. Moreover, this study employs network externalities and transition costs as reinforcement variables to examining whether network externalities and transition costs will significantly impact enterprises e-marketplace adoption at the post-decision stage. The empirical evidence clearly supports that adopting-firms will be markedly affected by network externalities when considering to staying in or existing current e-marketplaces as well as switching to another one, meanwhile transition costs do not play an influential role for either adopting-firms or non-adopting-firms e-marketplace adoption at the post-decision stage.

Furthermore, with the fast and continuous rise of organizational investments in IT/IS-based product/service adoption, more research highlighting on understanding company-level technology adoption is undoubtedly required. Besides, although many surveys (Raisch, 2005) reported that a significant proportion of bricks-and-mortar trading activities has shifted into electronic buying and selling via e-marketplaces in North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific since 2002, surveys taken in mid 2003 and early 2004 (Yu, 2004; Yu and Chang, 2005) revealed that the adoption rate of the e-marketplace among Taiwanese enterprises was only 18.92% and 23.48%,

respectively, much lower than expected. Giving that Taiwan is theworld’s13thlargest trading nation and is heavily dependent on exports due to limited domestic market scale, Taiwanese firms seem should have more willing to use e-marketplaces to expand their global trade opportunities. Hence, more studies from different perspectives to explore Taiwanese enterprise e-marketplace adoption are also necessary. As a result, this study may fulfill the above needs.

To verify whether TAM effectively predict enterprises e-marketplace adoption at the pre- and in-decision stages as well as whether network externalities and transition costs markedly change or reverse enterprises previous e-marketplace adoption choice at the post-decision stage, this work takes DOI, TAM, network externalities and transition costs into a three-stage model of pre-decision, in-decision, and post-decision. Since this is the first work using a theoretic structure to investigate firm-level technology adoption, this investigation only represents a starting point to draw attention, not a final work, for understanding organizational technology adoption. More research is definitely required to verify and enhance the validity and generalization of the methodology used in this study.

Finally, 如同其他實證的研究 some limitations exist in this study. First, this work is not a longitudinal study. That is, the three-stage analysis is based on a snap-shot questionnaire survey rather than observing the same respondents over time through pre-decision, in-decision, to post-decision. Therefore, future works may conduct a longitudinal study to examine whether TAM, network externalities and transition costs significantly influence enterprise technology adoption at pre-decision stage, and reverse enterprise original decision at the post-decision stage. Second, owing to the samples being limited to Taiwanese enterprises, cautious is needed in generalizing the findings of this study to other countries with different industry structures or cultures. Third, the work did not collect the respondent personal data, which may be criticized.

REFERENCES

1. Adams, D. A., Nelson, R. R., and Todd, P. A. “Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of information,”MIS Quarterly (16:2) 1992, pp:227-247.

2. Aisbett, J. Lasch, R. and Pires, G. “A decision-making framework for adoption of e-procurement,”International Journal of Integrated Supply Management (1:3)

2005, pp:771-798.

3. Allen, D. “New telecommunications services: network externalities and critical mass,”Telecommunications Policy (12:3) 1988, pp:257-271.

4. Angeles, R. “Revisiting the role of Internet-EDI in the current electronic commerce scene,”Logistics Information Management (13:1) 2000, pp:45-50. 5. Asvanund, A., Clay, K., Krishnan, R. and Smith, M. D. “An empirical analysis of

network externalities in peer-to-peer music-sharing networks,” Information

Systems Research (15:2) 2004, pp:155-174.

6. Au, Y. A. and Kauffman, R. J. “Should we wait? Network externalities, compatibility, and electronic billing adoption,” Journal of Management

Information Systems 2001 (18:2), pp:47-63.

7. Bakos, Y. “The emerging role of electronic marketplaces on the Internet,”

8. Bhattacherjee, A. “Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model,”MIS Quarterly (25:3) 2001, pp: 351-370. 9. Brynjolfsson, E. and Kemerer, C. F. “Network externalities in microcomputer

software: An econometric analysis of the spreadsheet market,”Management

Science (42:12) 1996, pp:1627-1647.

10. Chang, C. W. “The development trend of e-marketplaces in Taiwan,”

http://www.moea.gov.tw/~ecobook/ms/9003/3-7.htm, 2001.

11. Chen, A. H. and Siems, T. F. “B2B e-marketplace announcements and shareholder wealth,”Economic & Financial Review (12:1) 2001, pp:12-22. 12. Chen, S. “Adoption of electronic commerce by SMEs of Taiwan,”Electronic

Commerce Studies (2:1) 2004, pp:19-34.

13. Choi, J. P. “Irreversible choice of uncertain technology with network externalities,”The Rand Journal of Economics (25:3) 1994, pp:382-401.

14. Choi, J. P. and Thum, M. “Market structure and the timing of technology adoption with network externalities,”European Economic Review (42:2) 1998, pp:225-244.

15. Clemons, E. K. and Kleindorfer, P. R. “An economic analysis of inter-organizational information technology,”Decision Support Systems (8:5) 1992, pp. 431-446.

16. Cooper, R. B. and Zmud, R. W. “Information technology implementation research: a technology diffusion approach,”Management Science (36:2) 1990, pp: 123-139.

17. Daniel, E. M., White A. and Ward, F. M. “Exploring the role of third parties in inter-organizational Web service adoption,”Journal of Enterprises Information

Management (17:5) 2004, pp:351-360.

18. Davis, F. D. “Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology,”MIS Quarterly (13:3) 1989, pp:319-340.

19. Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P. and Warshaw, P. R. “User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models,”Management Science (35:8) 1989, pp:982-1003.

20. Deng, X., Doll, W. J., Hendrickson, A. R. and Scazzero, J. A. “A multi-group analysis of structural invariance: An illustration using the technology acceptance model,”Information & Management (42:5) 2005, pp: 745-759.

21. Economides, N. “The economics of network,”International Journal of Industrial

Organization, (14:6) 1996, pp: 673-699.

22. Farrell, J. and Saloner, G. “Installed base and compatibility:Innovation, product pre-announcements, and predation,”The American Economic Review (76:5) 1986, pp.940-955.

23. Gallaugher, J. M. and Wang, Y. M. “Understanding network effects in software markets: Evidence from web server pricing,”MIS Quarterly (26:4) 2002, pp: 303-327.

24. Gefen, D. and Straub, D. “The relative importance of perceived ease of use in IS adoption: A study of e-commerce adoption,”Journal of the Association for

Information Systems (1:1) 2000, pp:1-30.

25. Gottschalk, P. and Abrahamsen, A. F. “Plans to utilize electronic marketplaces: the case of B2B procurement markets in Norway,”Industrial Management &

Data Systems (102:5) 2002, pp:325-331.

26. Grewal, R., Comer, J. M. and Mehta, R. “An investigation into the antecedents of organizational participation in business-to-business electronic markets,”Journal

27. Grieger, M. "Electronic marketplaces: A literature review and a call for supply chain management research," European Journal of Operational Research (144:2) 2003, pp:280-294.

28. Grover, V. and Goslar, M. D. “Theinitiation, adoption, and implementation of telecommunications technologies in U.S. organization,”Journal of Management Information Systems 1993 (10:1), pp:141-163.

29. Guilherme, D. P. and Aisbett, J. “The relationship between technology and strategy in business-to-business market: The case of e-commerce,”Industrial

Marketing Management (32:4) 2003, pp:291-306.

30. Heide, J. B. and Weiss, A. M.“Vendorconsideration and switching behavior for buyers in high-technology markets”, Journal of Marketing (59:4) 1995, pp:30-43.

31. Hoppe, H. C. “Second-mover advantages in the strategic adoption of new technology under uncertainty,”International Journal of Industrial Organization (18:2) 2000, pp: 315-338.

32. Hoyle, R. H. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications, Sage, Thousand Oaks, California, 1995.

33. Hu, P. J., Vhau, P. Y. K., Sheng, O. R. L. and Tam, K. Y. “Examining the technology acceptance model using physician acceptance of telemedicine technology,” Journal of Management Information Systems (16:2) 1999, pp:91-112.

34. Huarng, F. and Chen, Y. T. “Relationships of TQM philosophy, methods and performance: A survey in Taiwan,”Industrial Management & Data Systems (102:3) 2002, pp:226-234.

35. Hung, S. Y. Liang, T. P. and Chang, C. M. “A meta-analysis of empirical research using TAM,”Journal of Information Management (12:4) 2005, pp:211-233. 36. Jackson, B. B. “Build customer relationships that last,”Harvard Business Review

(63:6) 1985, pp:120-128.

37. Kaplan, S. and Sawhney M. “E-hubs: The new B2B marketplaces,”Harvard

Business Review (78:3) 2000, pp:97-103.

38. Karahanna, E., Straub, D. W. and Chervany, N. L. “Information technology adoption across time: a cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs,”MIS Quarterly (23:2) 1999, pp:183-213.

39. Kauffman, R. J., McAndrews, J. J. and Wang Y. M. “Opening the “black box”of network externalities in network adoption,”Information Systems Research (11:1) 2000, pp:61-82.

40. Kendall, J., Tung, L. L., Chua, K. H., Ng, C. H. D. and Tan, S. M. “Electronic commerce adoption by SMEs in Singapore,”Proceedings of the 34th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2001, pp:1-10.

41. King, R. C. and Gribbins, M. L. “Adoption of organizational Internet technology: Can current technology adoption models explain web adoption strategies in small & mid-sized organizations?,”International Journal of Management Theory and

Practices (4:4) 2003, pp:49-61.

42. Klemperer, P. “Competition when consumer have switching cost: An overview with applications to industrial organization, macroeconomics, and international trade,”Review of Economic Studies (62:4) 1995, pp:515-540.

43. Le, T. T. “Business-to-business electronic marketplaces: evolving business models and competitive landscapes,” International Journal of Service Technology and Management (6:1) 2005, pp:40-52.

44. Lee, J., Lee, J. and Lee, H. “Exploration and exploitation in the presence of network externalities,”Management Science (49:4) 2003, pp:553-570.

45. Legris, P., Ingham, J. and Collerette, P. “Why people use information technology? A critical review of the technology acceptance model”, Information &

Management (40:3) 2003, pp:191-204.

46. Lu, D. and Antony, F. “Implications of B2B marketplace to supply chain development,”The TQM Magazine (15:3) 2003, pp:173-179.

47. Lundblad, J. P. “A review critique of Rogers’diffusion of innovation theory as it applies to organizations,”Organization Development Journal (21:4) 2003, pp: 50-64.

48. Malone, T. W., Benjamin, R. I. and Yates J. “Electronic markets and electronic hierarchies: effects of information technology on market structure and corporate strategies,”Communication of ACM (30:6) 1987, pp: 484-497.

49. Malone T. W. and Crowston K. “The interdisciplinary study of coordination,”

ACM Computing Surveys (26:1) 1994, pp: 87-119.

50. O'Callaghan, R., R. J. Kaufmann, and B. R. Konsynski “Adoption correlates and share effects of electronic data interchange systems in marketing channel,”

Journal of Marketing (56:1) 1992, pp:45-56.

51. Ordanini, A, Micelli, S. and Di Maria, E. “Failure and success of B-to-B exchange business models: A contigentanalysis of their performance,”European

Management Journal (22:3) 2004, pp:281-289.

52. Piccinelli, G., Di Vitantonio, G.. and Mokrushin L. “Dynamic service aggregation in electronic marketplaces,”Computer Networks (37:1) 2001, pp:95-109.

53. Premkumar, G.., Ramamurthy, K. and Nilakanta, S. “Implementation of electronic data interchange: An innovation diffusion perspective”, Journal of

Management Information Systems (11:2) 1994, pp:157-186.

54. Pollard, C. “E-service adoption and use in small farms in Australia: Lessons learned from a government-sponsored program,”Journal of Global Information

Technology Management (6:2) 2003, pp:45-63.

55. Poon, S. and Swatman, P. M. C. “An exploratory study of small business Internet commerce issues,”Information & Management (35:1) 1999, pp:9-18.

56. Raisch, W. D. The E-marketplace: Strategies for Success in B2b E-commerce, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2005.

57. Ratnasingam, P. Gefen, D., and Pavlou, P. A. “The role of facilitating conditions and institutional trust in electronic marketplaces,” Journal of Electronic

Commerce in Organizations (3:3) 2005, pp:69-82.

58. Rayport, J. F. and Sviokla, J. F. “Managing in the marketplace,”Harvard

Business Review (72:6) 1994, pp:141-151.

59. Reimers K. and Li, M. “Should buyers try to shape IT markets through non-market (collective) action? Antecedents of a transaction cost theory of network effects,”International Journal of IT Standards & Standardization

Research (3:1) 2005, pp:44-67.

60. Rogers, E. M. Diffusion of Innovations (5thedition), Free Press, New York, 2005. 61. Rohlfs, J. “A theory of interdependent demand for a communications service,”

The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science (5:1) 1974, pp:16-21.

62. Sculley, A. B. and Woods W. A. B2B exchanges: The killer Application in the

Business-to-business Internet Revolution, HarperCollins, New York, 2001.

63. Shang, K. C. and Marlow, P. B. “Logistics capability and performance in Taiwan's major manufacturing firms,”Transportation Research Part E: Logistics

64. Shapiro, C. and Varian, H. R. Information Rules: A Strategic Guide to Network

Economic, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA, 1998.

65. Singh, R., Salam, A. F. and Iyer, L. “Agents in e-supply chains,”

Communications of The ACM (48:6) 2005, pp:109-115.

66. Slade, P. and Van Akkeren, J. “Business on-line? An empirical study of factors leading to the adoption of Internet technologies by Australian SMEs,”Australian

Journal of Information Systems (10:1) 2002, pp:50-65.

67. Sohn, Y. S., Joun, H. and Chang, D. R. “A model of consumer information search and online network externalities,”Journal of Interactive Marketing (16:4) 2002, pp:2-14.

68. Squire, L. “Some aspects of optimal pricing for telecommunications,”The Bell

Journal of Economics and Management Science (4:2) 1973, pp.515-523.

69. Stewart, T. A. “Boom time on the new frontier,”Fortune (128:7) 1993, pp.153-162.

70. Stockdale, R. and Standing, C. “Benefits and barriers of electronic marketplace participation: an SME perspective,” Journal of Enterprises Information

Management (17:4) 2004, pp:301-311.

71. Straub, D., Limayem, M. and Karahanna-Evaristo, E. “Measuring system usage: Implications for IS theory testing”, Management Science (41:8) 1995, pp:1328-1342.

72. Tao, Y., Ho, I. and Yeh, R. “Building a user-based model for web executive learning systems –A study of Taiwan’s medium manufacturing companies,”

Computer & education (36:4) 2001, pp:317-332.

73. Thong, J. Y. L. and Yap, C. S. “CEO characteristics, organizational characteristics and information technology adoption in small business,”Omega (23:4) 1995, pp:429-442.

74. Thong, J. Y. L. “An integrated model of information systems adoption in small business”, Journal of Management Information Systems (15:4) 1999, pp:187-214.

75. Tran, S. “The strategic implications of electronic marketplaces: from commercial transactions to inter-organizational supply chain activities,” International

Journal of Business Performance Management (18:1) 2006, pp:47-63.

76. Travica, B. “Diffusion of electronic commerce in developing countries: The case of Costa Rica,”Journal of Global Information Technology Management (5:1) 2002, pp:4-24.

77. Venkatesh, V. and Davis, F. D. “A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies,”Management Science (46:2) 2000, pp:186-204.

78. Wang, E. T. G. and Seidmann, A. “Electronicdata interchange: Competitive externalities and strategic implementation policies,”Management Science (41:3) 1995, pp:401-418.

79. Weiss, A. M. and Anderson, E. “Converting from independent to employee sales forces: The role of perceived switching costs,”Journal of Marketing Research (29:1) 1992, pp:101-115.

80. Wu, J. H. and Wang, S. C. “What drives mobile commerce? An empirical evaluation of the revised technology acceptance model,” Information &

Management (42:5) 2005, pp:719-729.

81. Yu, C.S.“To explorethefactorsofaffecting acompany’sdecision to adopt,not adopt, switch or exit the e-marketplace,”Proceedings of Thirty-Fifth Annual

Management, pp. 69-76, March 2-6 2004. (Florida, USA)

82. Yu, C. S. and Chang, Y. C. “Characteristics of Firms Adopting and Non-Adopting E-Marketplaces: Using Clustering Analysis to Explore,”

Electronic Commerce Studies (3:3) 2005, pp:265-288.

83. Zain, M., Rose, R. C., Abdullah, I. and Masrom, M. “The relationship between information technology acceptance and organizational agility in Malaysia,”

Table 1. Research construct definitions and questionnaire items

Construct Operational Definition Sources of Corresponding Questionnaire Items

Usefulness

The degree to which a firm evaluates how many benefits can be gained from adopting the e-marketplace.

Q1-8 used to assess usefulness are inferred from the literature (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989; O' Callaghan et al., 1992; Premkumar et al., 1994; Premkumar and Roberts, 1995; Thong et al., 1995; Thong, 1999; Gottschalk and Abrahamsen, 2002).

Ease-of-use

The degree to which a firm evaluates how many efforts required to adopt the e-marketplace.

Q9-12 used to assess ease-of-use are inferred from the literature (Davis, 1989; Davis et al., 1989; O' Callaghan et al., 1992; Premkumar et al., 1994; Premkumar and Roberts, 1995; Thong et al., 1995; Thong, 1999; Gottschalk and Abrahamsen, 2002).

IC-of-Firm

The degree from the inside company characteristics to influence a firm’s decision on the e-marketplace adoption.

Q13-24 used to assess IC-of-Firm are inferred from the literature (O' Callaghan et al., 1992; Grover and Goslar, 1993; Thong et al., 1995; Thong, 1999; Gottschalk and Abrahamsen, 2002).

OCE-of-Firm

The degree from the outside competitive environment to influence a firm’s decision o the e-marketplace adoption.

Q25-37 used to assess OCE-of-Firm are inferred from the literature (O' Callaghan et al., 1992; Grover and Goslar, 1993; Gottschalk and Abrahamsen, 2002).

Top management willingness to

adopt

The degree from the top management willingness to adopt e-marketplaces.

Q38 used to assess Firm willingness to adopt e-marketplaces (Thong et al.,

1995; Thong, 1999).

Network Externalities

The degree to which a firm assesses that the benefits derived by adopting the e-marketplace rises with the

Q39-44 used to assess NE are inferred from the literature (Farrell and Saloner, 1985, 1986; Katz and Carl, 1985, 1992; Sohen et al., 2002).

number of participants using that e-marketplace.

Transition Cost

The degree to which a firm assesses that the cost of switching e-marketplaces, from non-adoption status to adoption status, from adoption status to non-adoption status,

or from the current

e-marketplace to another.

Q45-51 used to assess TC are inferred from the literature (Heide and Weiss, 1993; Klemperer, 1988, 1995; Shapiro and Varian, 1998).

Table 2 The Profile of Respondents

Category Item Mean or

Frequency

Std. Dev. or Percentice

Number of Employee (Person) 1069.41 2493.71

Capital (Millions of NT$) 2066.56 2902.24

Revenue (Millions of NT$) 7689.99 37705.36

Annual membership fee (NT$) 42194.12 60817

Member size of the adopted e-marketplace (Person) 20808.67 48517.84 Chemistry, Cement,

Petrochemistry 22 10.89%

Semiconductor 12 5.94%

Textile 14 6.9%

Optics, Machinery, and Metal 28 13.9%

Electronics and Information 63 31.2%

Automobile 15 7.4% Steel 12 5.9% Medicine 5 2.48% Food 7 3.47% Industry Type Others 24 11.88% Direct 48 51.07% Indirect 11 11.70% Direct vs. Indirect Unknown 35 37.23% Vertical 18 19.15% Horizontal 8 8.51% Vertical vs. Horizontal Unknown 68 72.34% Buyer-Dominated 18 19.15% Seller-Dominated 9 9.57% Third-party Dominated 10 10.64% Type of e-Marketplaces for Adopting Firms Buyer-, Seller-, or Third-party Dominated Unknown 57 60.64% Direct 36 33.33% Indirect 5 4.63% Direct vs. Indirect Unknown 67 62.04% Vertical 17 15.74% Horizontal 7 6.48% Vertical vs. Horizontal Unknown or Both 84 77.78% Type of e-Marketplaces for Non-Adopting Firms Buyer-, Buyer-Dominated 6 5.56%

Seller-Dominated 0 0% Third-party Dominated 11 10.18% Seller-, or Third-party Oriented Unknown 91 84.26% < 10% 39 41.49% 10%~20% 15 15.96% 20%~30% 23 24.47% 30%~40% 5 5.32% 40%~50% 3 3.19% 50%~60% 2 2.13% 60%~70% 3 3.19% 70%~80% 2 2.13% 80%~90% 2 2.13% Percentage of revenue generated from e-Marketplaces for Adopting Firms >90% 0 0%

Benefits gained less than

expected 30 31.71%

Benefits gained equal to expected 23 24.39%

The benefit your firm gained from e-marketplace

and expected before using the

e-marketplace Benefits gained more thanexpected 41 43.90%

Table 3 The summary of Factor analysis Construct Named Dimension Q# Factor Loading Eigenvalue Cumulated Variance Cronback α Upgrade Transaction Efficiency Q6 Q7 Q5 Q8 0.930 0.903 0.882 0.842 3.282 46.89% 0.910 Usefulness Expand Transaction opportunities Q2 Q1 Q3 0.958 0.936 0.830 2.585 83.82% 0.895 0.87 Ease-of-use Q10 Q11 Q9 0.936 0.926 0.907 2.557 85.23% 0.91 Degree of workflow speed (Speed) Q21 Q22 Q23 Q24 0.840 0.839 0.812 0.796 3.085 25.712% 0.875 Degree of workflow standardization (Standardization) Q17 Q18 Q19 Q20 0.806 0.772 0.738 0.732 2.837 49.351% 0.825 IC-of-Firm Extent of workflow computerization (Computerization) Q13 Q14 Q15 Q16 0.847 0.783 0.712 0.641 2.552 70.618% 0.840 0.78

Stimulation from partners, competitors, or government (Peers and Government) Q25 Q26 Q27 Q28 Q29 Q30 Q31 Q32 0.773 0.829 0.881 0.871 0.805 0.778 0.741 0.754 5.285 40.652% 0.927 OCE-of-Firm Level of transparency of a competitive environment (Industry Transparency) Q33 Q34 Q35 Q36 Q37 0.886 0.906 0.906 0.828 0.874 4.076 72.007% 0.935 0.91 Network Externalities Q39 Q40 Q41 Q42 Q43 0.894 0.930 0.873 0.886 0.885 3.976 79.92% 0.94 Sunk Cost Q45 Q46 Q47 Q48 0.854 0.905 0.895 0.651 4.342 43.552% 0.933 Transition Cost Switch Loss Q49 Q50 Q51 0.853 0.755 0.871 1.148 78.417% 0.941 0.89

Table 4 Summary of regression-test results Dependent

variables

Independent variables

Standardized

beta value t-value T-value Adjusted R

2 Top Management willingness to adopt usefulness ease-of-use IC-of-Firm OCE-of-Firm 0.148 0.869 0.106 0.636 3.165**(H1) 28.830***(H2) 3.476**(H5) 15.117***(H6) 310.243*** 0.863 usefulness ease-of-use 0.471 7.549***(H3) 56.992*** 0.218 Top Management willingness to adopt usefulness ease-of-use 235.108*** 0.691 Top Management willingness to adopt IC-of-Firm OCE-of-Firm 34.495*** 0.254

*significant at 0.05 level, ** significant at 0.01 level, *** significant at 0.001 level

Table 5 T-test results Adopt or not

Yes No t-Value

Top Management willingness to adopt

4.0174 3.7425 3.924***(H4)

Continuous Using Planning to Exit or Switch Continuous not Using Planning to Use

Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No

5.357 4.756 N/A 2.245* (H7) N/A 4.756 5.350 N/A -2.206* (H8) 5.355 5.014 N/A 1.354 (H9) Network Externalities N/A N/A 5.047 5.015 0.142 (H10) 4.774 4.736 N/A 0.162 (H11) N/A N/A 4.772 4.615 0.765 (H12) 4.844 4.836 N/A 0.024 (H13) Transition Costs N/A 4.836 4.819 N/A 0.055 (H14)

N/A means Not Applicable ;***P value < 0.001;**P value < 0.01;*P value < 0.05

Table 6. Summary of logical regression test for Hypothesis 4

Dependent Variables

Independent Variables Beta value S.E. Wald chi-square Model Summary Adoption or not Top Management willingness to adopt 1.176 0.323 13.278*** X2(df=1) = 15.187, P-value=0.000, -2 log likelihood = 258.794, Overall correct classification rate = 62.1% (60.6% for adopters

Fig. 2 Adapted from Technology acceptance model (Davis et al., 1989) Usefulness Ease-of-use Willingness to use Adoption or not Confirmation Decision Implementation Knowledge Persuasion Degree of understanding or knowing the innovation Readiness of inclining to the innovation Adoption or rejection Continued adoption Late adoption Discontinuance Continued rejection

Pre-decision stage in-decision Post-decision stage stage

Fig. 3 The concepturized research structure

Pre-decision stage in-decision Post-decision stage stage Usefulness Ease-of-use Willingness to adopt Adoption or not Adopt Not Adopt Continuous Using Planning to Exit/Switch Continuous not Using Planning to Use Network Externalities Transition Costs

H12 H14 H13 H11 H10 H9 H8 H7 H4 H6 H5 H2 H3 H1

Fig. 4 The presented research structure

Pre-decision stage in-decision Post-decision stage stage IC-of-Firm Ease-of-use Willingness to adopt Adoption or not Adopt Not Adopt Continuous Using Planning to Exit/Switch Continuous not Using Planning to Use Network Externalities Transition Costs Usefulness OCE-of-Firm