Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=whmm20

Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management

ISSN: 1936-8623 (Print) 1936-8631 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/whmm20

Examining an extended technology acceptance

model with experience construct on hotel

consumers’ adoption of mobile applications

Yu-Chih Huang, Lan Lan Chang, Chia-Pin Yu & Joseph Chen

To cite this article: Yu-Chih Huang, Lan Lan Chang, Chia-Pin Yu & Joseph Chen (2019): Examining an extended technology acceptance model with experience construct on hotel

consumers’ adoption of mobile applications, Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, DOI: 10.1080/19368623.2019.1580172

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1580172

Published online: 06 Mar 2019.

Submit your article to this journal

Examining an extended technology acceptance model with

experience construct on hotel consumers

’ adoption of mobile

applications

Yu-Chih Huanga, Lan Lan Changb, Chia-Pin Yu cand Joseph Chend

aNational Chi-Nan University, Department of Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management, Nantou, Taiwan; bAsia University, Department of Leisure and Recreation Management, Taichung, Taiwan;cSchool of Forestry

and Resource Conservation, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan;dSchool of Public Health, Indiana

University Bloomington, Bloomington, USA

ABSTRACT

Given the accelerating adoption of apps and mobile technology in the hospitality and tourism industry, it is critical to understand cus-tomer experience of mobile apps as emerging marketing platforms to promote services and products. The objective of this research is to develop an integrative model that extends the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) with the experience construct and to exam-ine the antecedents that influence hotel consumer behavioral inten-tions toward mobile app usage. Thefindings of this study show that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness have positive impacts on hotel consumers’ experiences of mobile apps, and perceived usefulness and user experience influence hotel apps acceptance by customers. Thefindings of this study can be used as valuable input for the development of constructive future smartphone applications within the hospitality industry and for design of strategies for hotel mobile commerce marketing programs to enhance engaging and interactive hotel consumer experiences.

摘要 鉴于应用程序和移动技术在酒店业和旅游业的应用日益普及,了解 移动应用程序作为新兴营销平台的客户体验对于推广服务和产品至 关重要.本研究的目的是建立一个整合模型,将技术接受模型 (TAM)与经验建构相结合,并检视影响酒店消费者使用移动应用 行为意向的前因.研究结果表明,感知的易用性和感知的有用性对酒 店消费者的移动应用体验有积极的影响,感知的有用性和用户体验 对酒店应用接受度有影响.本研究的结果可作为酒店业未来智能手机 应用开发的宝贵投入,也可用于酒店移动商务营销计划的策略设 计,以增强酒店消费者的参与和互动体验. KEYWORDS

Hospitality industry; mobile applications; experience economy; technology acceptance model; behavioral intentions

Introduction

Technical innovations in the tourism industry profoundly influence the production, distribution, and consumption of hospitality and tourism products and services (Buhalis & Amaranggana, 2015; Werthner & Klein, 1999; Xiang, Magnini, & Fesenmaier, 2015). CONTACTChia-Pin Yu simonyu@ntu.edu.tw School of Forestry and Resource Conservation, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Color versions of one or more of thefigures in the article can be found online atwww.tandfonline.com/whmm.

With the increasing popularity of mobile devices, mobile commerce provides consumers with the ability to search for hotel and travel information from any location at any time. The service providers in the hospitality and tourism industries also utilize mobile technol-ogy to enhance brand awareness (Kim & Adler, 2011), enrich tourist experience and overall tourist satisfaction (Lee, Lee, & Ham, 2013), and increase customer loyalty (Kim, Park, & Morrison, 2008). Hospitality and tourism businesses have begun to develop smartphone phone applications (apps) to communicate marketing messages to consumers that influence travel decision-making and consuming behavior (Eden & Gretzel, 2012). Smartphone technologies support new communication patterns between travelers and service providers, entailing a consumer experience co-creation that affects consumer purchase decisions (Dickinson et al.,2014; Wang, Li, & Li,2013).

Numerous international hotel brands, such as Marriott International, Mandarin Oriental, and Intercontinental Hotel Group, have used smartphone applications to provide travel information, property details, room reservations, and promotional offers (Kim, 2012). Wang, Xiang, Law, and Ki (2016) suggest that the adoption of mobile technology and its association with apps have transformed hotel service by facilitating the management func-tions of marketing and distribution. Additionally, the use of hotel mobile applicafunc-tions not only increases consumer loyalty but also enhances traveler interaction (Adukaite, Reimann, Marchiori, & Cantoni, 2013). Specifically, travel-related applications facilitate marketing

functions, distribution, advertising, ancillary services, product personalization, destination guiding, and consumer relationship management (Chen, Murphy, & Knecht,2016; Morosan & DeFranco, 2015). Furthermore, the potential of mobile apps in the hotel industry is strategically important to reduce administrative and communication costs for information dissemination (Rivera, Gregory, & Cobos,2015).

Xiang, Wang, O’Leary, and Fesenmaier (2015) indicated that it is critical to understand customers’ experiences of mobile apps and their influence on behavioral intentions. The framework of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has received considerable attention from information technology scholars, and significant research efforts have been directed to study user acceptance for various technology applications. The TAM, rooted in the psycho-logical theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein,

1980), has been applied to explain consumer acceptance of information technology in numerous contexts, such as e-learning (Cheung & Vogel,2013; Schoonenboom,2014); social media usage (Ayeh,2015; Rauniar, Rawski, Yang, & Johnson,2014); web commerce (Ashraf, Thongpapanl, & Auh, 2014; Escobar-Rodríguez & Carvajal-Trujillo, 2014); entertainment technology (Dogruel, Joeckel, & Bowman, 2015); healthcare (Ahlan & Ahmad, 2015); and mobile commerce (Baptista & Oliveira,2015; Joo & Sang,2013).

Although TAM has empirically explained the acceptance and usage of information technology in various contexts, many extensions to the original TAM have been proposed to improve understanding of user acceptance behavior in specific contexts (e.g., Agag & El-Masry, 2016; Gamal Aboelmaged, 2010; Muñoz-Leiva, Climent-Climent, & Liébana-Cabanillas, 2017). As Im and Young Im and Hancer (2014) suggested, because TAM mainly focuses on the individual’s cognitive characteristics, for technology that users voluntarily choose to use, a hedonic perspective of the acceptance of information technol-ogy needs to be studied further. Recent research has extended the TAM to incorporate hedonic constructs as a theoretical underpinning in understanding user experience of information technology. For example, Childers, Carr, Peck, and Carson (2001) extended

TAM by adding perceived enjoyment; Hsiao, Chang, and Tang (2016) extended TAM by adding satisfaction; Jung, Perez-Mira, and Wiley-Patton (2009) incorporatedflow experi-ence; and Wendy Zhu and Morosan (2014) studied TAM by integrating playfulness. Various scholars have suggested expansion of the TAM research framework to incorporate an experience economy perspective in explaining consumer usage of information technol-ogy. For example, McLellan (1999) in educational technology, Seo (2013) in electronic sports, and tom Dieck, Jung, and Rauschnabel (2018) in science festival augmented reality. However, empirical studies that integrate TAM and experience economy aspects to investigate consumer information technology usage in tourism and hospitality contexts remain limited. Morosan and DeFranco (2016) indicated that mobile app experience is critical in the context of hospitality and tourism marketing, but the mechanism of consumers’ intention development remains unknown. Mobile apps play an important role in fostering customer involvement, which in turn contributes to brand loyalty, and thefirst challenge in using mobile apps is to capture customer attention (Sprosen,2014; Zhao & Balague,2015). As mobile technology advances, the mobile service environment plays a crucial role in connecting customer and hotel, such as booking a hotel and requesting services (Ozturk, Nusair, Okumus, & Hua, 2016). In order to sustain the success of hospitality businesses, Lee and Jeong (2012) indicated a careful design of service environments is necessary, particularly in physical and virtual aspects. Scholars (e.g., Dube & Helkkula,2015; Liu, Li, Chen, & Balachander,2017) call for more research to explore product design strategies and investigation of the role of mobile environments on custo-mers’ mobile app experiences. Lee (2018) further indicated that it is important to under-stand customer service experience and how the mobile platform is designed to meet their needs and enhance engagement behavior. In this context, given the wide adoption of the extended TAM model in understanding user experience in human and technology inter-action, the experience economy model is considered to be a valuable framework for understanding users’ experiences (Jung, tom Dieck, Lee, & Chung, 2016; tom Dieck et al., 2018). Therefore, building a conceptual model to investigate users’ intentions to

use hotel apps by accessing their experiences provides advantages to hospitality research. To this end, the objective of this research is to develop an integrative model that extends TAM with an experience construct and examines the antecedents that influence hotel consumer behavioral intentions toward mobile apps usage based on user experience. This study extends the current literature by incorporating the experience construct and TAM to investigate hotel consumers’ smartphone apps experiences. From a theoretical point of view, this research empirically examines the proposed model in understanding significant factors influencing customers’ intentions, explaining the importance of mobile commerce to the hospitality business. While a concern of TAM is that it is used to explain user intention to accept new technology, limited research articulating consumer experience and adoption was found in the context of Taiwan mobile apps studies, particularly in the hospitality business. The TAM is still considered a useful model in explaining behavior from an information system perspective, and modified models of TAM are popular in consumer contexts of research (Mo Kwon, Bae, & Blum, 2013). In this regard, from a managerial perspective, thefindings of this study provide a structural understanding of using mobile applications in developing promotion and design strategies for hotel market-ers and service providmarket-ers in Taiwan.

Literature review

Technology acceptance model

Davis (1989) proposed TAM for explaining users’ behavioral intentions and usage of

information technology, suggesting that the TAM demonstrated a substantial proportion of the variance of consumer behavior intentions to use a technological innovation. TAM postulates that imperative determinants of technology acceptance and behavioral inten-tions are perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and attitude (Venkatesh, 2000; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). Previous studies suggested that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are depicted as having a direct effect on behavioral intentions concerning information technology but omitted the construct of attitude due to it being a weak predictor of behavioral intention in specific contexts, such as smartphone shopping (Agrebi & Jallais,2015), electronic mail systems (Szajna,1996), online learning (Saadé & Bahli, 2005), e-commerce (Pavlou, 2003), and mobile commerce (Wu & Wang, 2005). Moreover, Davis (2003) pointed out that consumer usage and acceptance of information technology relies on the theoretical constructs of perceived ease of use and usefulness, suggesting the exclusion of the attitude construct in TAM. Perceived ease of use is defined as“the degree to which a person believes that using a particular information system would enhance his/her job performance,” whereas the construct of perceived usefulness is defined as “the degree to which an individual believes that using a particular system is free of physical and mental effort” (Davis,1989, p. 320). Pavlou’s (2003) study indicated that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness serve as direct antecedents to predict-ing online consumer behavioral intentions, explainpredict-ing the acceptance of online transaction behavior. Consumer assessment of ease of use and usefulness of the e-vendor’s website influence the consumer’s behavioral intention to use a business-to-consumer website (Gefen, Karahanna, & Straub,2003).

Over the past decades, researchers have extended TAM to incorporate additional variables in explaining online consumer behavior with empirical support such as con-textual factors of gender difference (Gefen & Straub, 1997), prior technology experience (Venkatesh & Morris,2000), information system quality (Kim, Lee, & Law,2008), external predictors of perceived risk (Kesharwani & Singh Bisht, 2012), users’ emotions (Lee,

Xiong, & Hu, 2012), perceived security (Morosan,2011), technology experience (Rivera et al.,2015), credibility theories (Ayeh, 2015), innovation diffusion theory (Lee, Hsieh, &

Hsu,2011),flow theory (Koufaris,2002) and task-technologyfit model (Lam, Cho, & Qu,

2007). Koufaris (2002) expanded TAM with flow experience to examine emotional and cognitive responses to visiting web-based shopping environments, suggesting that per-ceived usefulness influences the experience of online consumers, which in turn affects their behavioral intentions. Ayeh (2015) extended TAM to incorporate source credibility theories in investigating acceptance and usage of consumer-generated media in travel planning, suggesting that the perceived ease of use and usefulness proved more salient in determining online consumers’ acceptance of consumer-generated media.

Previous studies have suggested that the experience aspect focuses on capturing peo-ple’s interactions with the technology to the extent that they enjoy this experience (Castañeda, Muñoz-Leiva, & Luque, 2007; Morgan-Thomas & Veloutsou, 2013; Van der Heijden,2004). According to Li, Dong, and Chen (2012) and Wu and Holsapple (2014),

such a perspective was found to be a significant predictor to outcomes related to usage and acceptance of information technology. Similarly, Ozturk et al. (2016) expanded TAM to incorporate the experiential construct of perceived hedonic value in investigating con-sumer behavioral intentions, suggesting that concon-sumers desire pleasure and enjoyable experiences from the use of information technology. A study examining social media sharing experiences by Kang and Schuett (2013) identified the hedonic construct of

perceived enjoyment as an influential factor affecting human and computer interaction. Wang, Liao, and Yang (2013), examining the determinants of behavioral intention of app users, suggested that consumer values of user experience played a crucial role in influen-cing intention to use information technology. Given the aforementioned information, it is logical to propose that the integration of the experience perspective with TAM could enrich the understanding of the determinants of consumers’ behavioral intentions in information technology contexts.

Experience economy

Pine and Gilmore (1998) proposed the“experience economy” and indicated how business is conducted by focusing on customer experience. According to Pine and Gilmore (1998, p. 97), four realms of experiences across both axes of customer immersion and level of participation are identified as entertainment, education, esthetics, and escapism. The enter-tainment experience entails an individual’s passive involvement, wherein the offerings engage customers’ attention. The esthetic experience involves passive participation wherein customers are highly immersed in the environment. The educational experience entails an active participation in which a customer is absorbed by the events, and escapist experiences involve total immersion in an environment. Examples of such experiences in mobile app contexts have been described in previous studies (see Sims, Williams, & Elliot, 2007 for a review). Based on the Experience Economy model and in the context of hotel mobile app experience, the experience of entertainment occurs in the form of a passive delivery of content such as pictures; education delivers information about hotel services, for example, while escapism refers to users’ active participation to escape from reality while using the app. The esthetic highlights an app experience that is attractive and pleasant. As such, these factors of a hotel mobile app influence users’ mobile technology acceptance.

More recently, scholars applied the concept of experience economy to further under-stand consumer experiences in the hospitality and tourism contexts (e.g., Andersson,

2007; Oh, Fiore, & Jeoung, 2007; Quadri-Felitti & Fiore, 2012; Song, Lee, Park, Hwang, & Reisinger, 2015). Oh et al. (2007) suggested that the experience dimension could be useful in capturing consumer lodging experience. Moreover, researchers found that the four dimensions of experience influence consumer satisfaction and behavioral intention (Hosany & Witham,2010; Mehmetoglu & Engen,2011; Park, Oh, & Park,2010; Quadri-Felitti & Fiore, 2012). The four realms of experience have been treated as individual dimensions (Liu, Huang, & Li,2018) or a higher order of construct (Manthiou, Lee, Tang, & Chiang, 2014) within various tourism-related contexts. tom Dieck, Jung, Kim, and Moon (2017) asserted that they “compared the effects of each of the four constructs on target variables and often concluded that only a few of them matter” (p.46). Moreover, Loureiro (2014) suggested that the uni-dimensionality of the experience economy con-struct provides more predictive power in explaining consumer experience. Thus, the

current study employed the uni-dimension of experience economy in investigating hotel consumer use of mobile apps.

Additionally, in the experience economy, service providers have become aware of the significance of creating unique consumer experiences beyond merely consuming products and services (Gilmore & Pine, 2002; Pine & Gilmore, 1998). Given online experiential marketing approaches and the inherently experiential nature of the hospitality industry, the emerging technologies offer sensory stimulations to communicate with consumers in supporting travel information search and decision-making processes (Gretzel & Fesenmaier,2003). Past studies have suggested that these realms of experiences are useful for explaining consumer experience and consumer behavior (Lee, Bruwer, & Song,2017; Venkatesh, Thong, & Xu,2012). The established body of research suggests that experience dimensions have the potential to better explain consumer behavior, particularly in the research on customer memory and loyalty (Manthiou et al., 2014); experiential value (Quadri-Felitti & Fiore, 2012); satisfaction and behavioral intentions (Radder & Han,

2015); consumer involvement and brand identification (Hwang & Lyu, 2015); and per-ceived value and emotion (Song et al.,2015).

Hypotheses development

The application of TAM in tourism literature has primarily focused on explaining tourist’s and hotel consumer’s acceptance and use of information technology (e.g., Kaplanidou & Vogt,

2006; Kim, Lee, & Law,2008; Morosan,2010; Munoz-Leiva, Hernández-Méndez, & Sánchez-Fernández,2012; Wang & Qualls,2007). A study of electronic word-of-mouth in consumer-generated media by Yang (2017) found that perceived usefulness and ease of use resulted in positive behavioral intentions to participate in a virtual community. Kim (2016) found that perceived ease of use and usefulness serve as determinants to customers’ behavioral intentions toward hotel tablet apps. tom Dieck et al. (2017) explored consumer acceptance and usage of social media networks in the context of luxury hotels, claiming that the perception of usefulness and ease of use indirectly predicted consumer’s behavioral intention to use social media to engage with a hotel. Recent studies have therefore demonstrated that TAM is an important research framework that can be used to understand consumer experiences of hospitality websites or related hospitality information technology.

Pine and Gilmore’s concept of experience economy has received considerable atten-tion in recent studies attempting to understand user experience of technological innovations. Mathwick, Malhotra, and Rigdon (2001) claimed that the concept of experience economy is an important theoretical dimension for understanding interac-tions between human behavior and technology that can predict consumer preference and patronage intentions. Moreover, Jeong, Fiore, Niehm, and Lorenz (2009) indicated that the four dimensions of experience are related to the perception of pleasure and website patronage intentions. Seo’s (2013) study of competitive computer gaming and virtual world consumption suggested that Pine and Gilmore’s concept of experience economy is useful in conceptualizing and exploring the consumer’s experiential value in the context of e-marketing. Verhagen, Feldberg, van den Hooff, Meents, and Merikivi (2011) explored users’ experiential value and satisfaction with virtual words, suggesting that perceived ease of use is a direct determinant of entertainment and escapist experience, as well as an influential factor for consumer satisfaction. A study

examining virtual reality visitor experience in museums by Jung et al. (2016) indicated that the experience of education, entertainment, escapism, and esthetics deriving from virtual reality technology interaction significantly influenced visitor experience, leading to influence tourist intention.

Prior studies (Castañeda et al.,2007; Liu, Pu, Guan, & Yang, 2016; Morgan-Thomas & Veloutsou,2013; Sheng & Teo,2012) suggest that consumer experience plays a mediating role between technology acceptance factors and behavioral intentions. Additionally, past research investigating experiential aspects of consumer behavior has articulated the mediating role on the relationship between consumer experience and behavioral inten-tions (e.g., Bilgihan, Nusair, Okumus, & Cobanoglu, 2015; Hausman & Siekpe, 2009; Huang, Backman, Backman, & Chang,2016; Jeong et al.,2009).

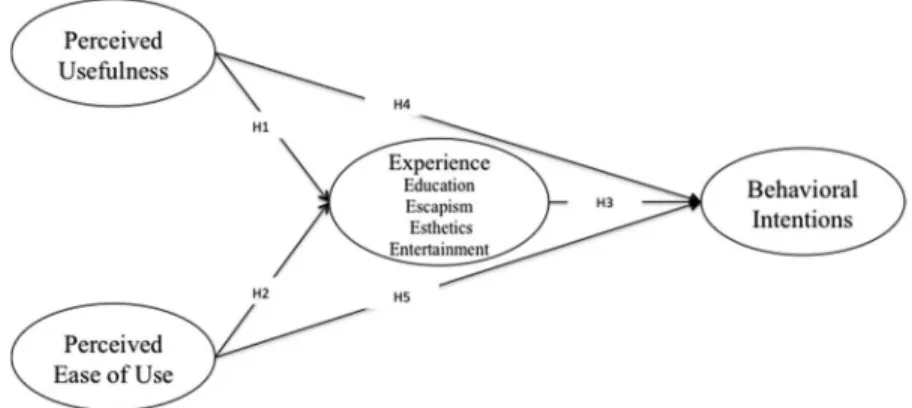

Given the aforementioned information, the current study proposes to investigate the mediating effect of experience with mobile apps as a link between technology acceptance and behavioral intentions. As current literature suggests, the concept of experience economy not only reflects the entertainment nature of the tourist experience but also captures the consumption experience of technology users. Therefore, the experience construct was utilized in this study for a better understanding of the use of smartphone apps in hospitality marketing. Based on the literature reviewed, the integrative model consists of TAM and the experience construct, and we believe the antecedents might positively influence behavioral intentions. The proposed conceptual model and hypotheses are shown in Figure 1.

H1: Hotel consumers’ perceived usefulness of a mobile app has a positive effect on the experience of the mobile app.

H2: Hotel consumers’ perceived ease of use of a mobile app has a positive effect on the experience of the mobile app.

H3: Hotel consumers’ experience of a mobile app has a positive effect on the behavioral intention to use the mobile app.

H4: Hotel consumers’ perceived usefulness of a mobile app has a positive effect on the behavioral intention to use the mobile app.

H5: Hotel consumers’ perceived ease of use of a mobile app has a positive effect on the behavioral intention to use the mobile app.

Methodology

Data collection

A quantitative survey approach (Bryman & Bell,2015) was used to investigate smartphone application consumption experience and its impacts on tourist behavioral intentions. A self-administered survey questionnaire using closed questions was used to collect information from participants. According to the Taiwan Tourism Bureau (2015), the Ken-ting National Park, in the southern beach area of Taiwan, is one of the top 3 tourism destinations for domestic travel. This study conducted a survey of consumers staying in Chateau Beach Resort, Gloria Manor, and Howard Hotel in the southern beach area of Taiwan in March and April of 2015. The general managers of these resorts were contacted by the researchers in order to acquire participation agreement; after receiving the parti-cipation agreement from three resorts, three well-trained graduate students conducted an on-site survey of hotel consumers. The participants were approached in the hotel lobby and asked whether they were willing to participate in the study. Following previous studies on mobile marketing (Persaud & Azhar,2012; Watson, McCarthy, & Rowley, 2013), the target population of the study consisted of individuals who have used smartphone apps to search for hotel and accommodation information at least once in the last six months. As suggested by Ozturk, Bilgihan, Nusair, and Okumus (2016), the participants in the study were chosen by asking screening questions regarding previous travel app experience. This convenience sampling approach was useful for collecting data where the respondents shared the characteristics of smartphone app usage for hospitality and tourism purposes (Watson et al.,2013). The study collected 490 valid samples, and the response rate of this study was 89%. Prior to conducting the survey, a pretest of the questionnaire was conducted to examine construct reliability with 133 samples. For the pilot test, tourists who have the experience of using smartphone apps in the southern part of Taiwan were recruited to participate in the pretest and to assess logical consistencies, ease of under-standing, and task relevance. Suggestions about the structure of the questionnaire from pretest participants were incorporated in the revision of the questionnaire. In addition, Cronbach’s alpha was used in the pilot test to identify poor items, and the correlated measure items were eliminated.

Measurements

Demographic information such as gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, highest academic achievement, residence, and current work status were collected. Each variable was measured at the categorical level, with categories consistent with those used by the Taiwan Census Bureau. Based on past TAM research (Davis,1989; Fetscherin & Lattemann,2008; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), this study modified the perceived ease-of-use scale to estimate subjective

perceptions of how easy the respondents thought a hotel app was to learn and use (e.g.,“I did not find it difficult to get the hotel app to do what I wanted it to do”) whereas perceived usefulness was used to assess the subjective estimation of task performance enhancement through the use of hotel apps (e.g.,“I believe that using hotel apps provides useful informa-tion in trip planning”). Both perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use scales consisted of three items. The four constructs of experience economy were modified from past studies (Jeong et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2007) consisting of entertainment, education, escapist, and esthetic dimensions. The construct of education was assessed with three items, such as“the experience of using hotel apps made me more knowledgeable,” to indicate the extent to which consumers are able to acquire information and knowledge about the hotel by using the mobile app; the experience of entrainment was measured with three items (e.g., “the experience of using the hotel apps is fun”) to indicate the extent to which consumers are able to enjoy the use of hotel mobile apps for pleasure; the experience of escapism was measured with three items (e.g.,“the experience of using hotel apps allows me to forget about my daily routine”) to indicate the extent to which consumers are able to be immersed in the experience; the esthetics experience was measured with four items, e.g., “the design of the hotel app is attractive” (Jung et al., 2016; Song et al.,2015). The assessment of behavioral intentions in this study was primarily based on the work of Ajzen and Driver (1992) and Kim et al. (2008), and includes items such as“I would recommend the use of hotel mobile apps to others for searching hotel and destination information.” All measurements were assessed on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree.

Results

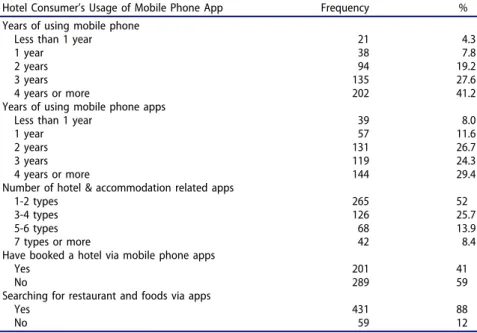

In terms of demographic characteristics of the respondents, females accounted for 55.5% of the respondents as shown inTable 1, and of the respondents, 57.8% were 26 to forty-five years old. A majority of respondents (64.5%) reported college as their highest level of educational attainment; 53.8% of the respondents were currently employed in the business and service industries, while 15.3% were students. In terms of the consumer’s usage of the mobile phone app, as seen inTable 2, the results found that 68.8% of consumers had used a mobile phone for over three years. Nearly 90% of the respondents reported that they had used mobile apps within the past year. Fifty-two percent of the respondents had 1–2 types of hotel and accommodation-related apps in their mobile phone. Forty-one percent of the respondents reported that they had booked the hotel via mobile phone apps. Eighty percent of the respondents had used the mobile phone apps to search for restau-rants and food, as well as tourist destinations.

According to Byrne (1998), the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) process was adapted to examine the causal relationship among the proposed constructs of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, experience, and behavioral intentions. As Yoon, Lee, and Lee (2010) suggested, SEM is designed to evaluate a series of interrelated dependence relationships among a set of latent (unobserved) constructs, and hence was found to be suitable for this study. Prior to SEM, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was con-ducted to assess the convergent and discriminant validity as well as the composite reliability of the factors for each construct (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988) by using EQS software. Following Bigné, Andreu, and Gnoth (2005), the Maximum Likelihood

Estimation was used in CFA to estimate the difference between the observed and model-implied variance-covariance matrix.

As per Satorra and Bentler’s (1994) suggestion, robust statistics was reported in this study to rectify multivariate non-normality in the confirmatory factor analysis. To assess whether the covariance matrix is equivalent to the observed covariance matrix (Hoyle,

1995), a number of robust fit indices were included: Satorra-Bentler (S-B) χ2,

Non-Table 1.Hotel consumer’s social demographic traits.

Social-demographic traits Frequency %

Gender Male 218 44.5 Female 272 55.5 Age 16-25 years old 55 11.6 25–36 years old 174 36.6 36–45 years old 164 34.5 46–55 years old 68 14.3 >55 years old 15 3.2 Education

High school & junior high school 97 19.8

College 316 64.5

Graduate school 77 15.7

Occupation

Farming, Fishing, and Forestry 10 2.0

Business 110 22.4

Civil Service 55 11.2

Service 154 31.4

Retired 10 2.0

Student 75 15.3

Housewife and other 76 15.5

Table 2.Hotel consumer’s usage of the mobile phone app.

Hotel Consumer’s Usage of Mobile Phone App Frequency %

Years of using mobile phone

Less than 1 year 21 4.3

1 year 38 7.8

2 years 94 19.2

3 years 135 27.6

4 years or more 202 41.2

Years of using mobile phone apps

Less than 1 year 39 8.0

1 year 57 11.6

2 years 131 26.7

3 years 119 24.3

4 years or more 144 29.4

Number of hotel & accommodation related apps

1-2 types 265 52

3-4 types 126 25.7

5-6 types 68 13.9

7 types or more 42 8.4

Have booked a hotel via mobile phone apps

Yes 201 41

No 289 59

Searching for restaurant and foods via apps

Yes 431 88

Normed Fit Index (NNFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Bollen’s (IFI) Fit Index, and Confidence Interval of RMSEA.

Examining the goodness offit index, the values for S-B χ2 = 574.68, p < 0.01, NNFI = 0.934, CFI = 0.944, and RMSEA = 0.063, IFI = 0.943, 90%. Confidence Interval of RMSEA = (0.057, 0.069) demonstrated that the model had an acceptable fit because the corre-sponding critical values are in line with the established criteria (Bentler & Hu,1995; Hair, Anderson, Tatham, & Black,1995). According to Anderson and Gerbing (1988), standar-dized factor loading and a t-test were used to examine the convergent validity. Bigné et al. (2005) pointed out that the convergent validity can be assessed by examining whether the different items that are measuring the same construct are strongly correlated and statis-tically significant. As displayed in Table 3, all t values associated with each indicator on corresponding constructs were significant (p < 0.05), and all standardized factor loadings were greater than 0.7, suggesting each indicator estimate loading on the underlying dimension (Tabachnick & Fidell,2007) and thus, the convergent validity of these indica-tors was verified (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

Table 3.Results of confirmatory factor analysis.

Construct/Item Factor meana Standardized factor loading

(t valuesb) CompositeReliability WeightedMaximal

PU (Perceived usefulness) 5.58 0.89 0.91

PU1 (Mobile app is useful information in trip planning) 5.56 0.84 (n/a) PU2 (Mobile app increases my productivity in trip planning) 5.56 0.90 (25.15) PU3 (Mobile app enables me to search travel information more

conveniently)

5.64 0.84 (23.17)

PEU (Perceived ease of use) 5.61 0.89 0.90

PEU1 (I did notfind it difficult to do what I wanted it to do) 5.62 0.84 (n/a) PEU2 (Learning to use was easy for me) 5.60 0.88 (22.67) PEU3 (It is easy for me to become skillful) 5.61 0.88 (23.39)

EDU (education) 5.37 0.79 0.86

EDU1 (The experience made me more knowledgeable) 5.49 0.74 (n/a) EDU2 (It was a real learning experience) 5.45 0.79 (18.09) EDU3 (It stimulated my curiosity to learn new things) 5.17 0.74 (15.47)

ENT (entertainment) 5.16 0.82 0.83

ENT1 (The app experience is fun) 5.16 0.79 (n/a)

ENT2 (The app experience was amusing to me) 5.17 0.79 (21.37) ENT3 (The app experience were very entertaining) 5.16 0.76 (21.03)

ESC (escapist) 4.67 0.81 0.82

ESC1 (I completely escaped from reality) 4.60 0.75 (n/a) ESC2 (I forgot about my daily routine) 4.75 0.82 (18.37) ESC3 (I felt I was in a different world) 4.66 0.73 (16.30)

EST (esthetics) 5.24 0.84 0.86

EST1 (The app experience provided pleasure to my senses) 5.34 0.72 (n/a) EST2 (The setting of app experience was attractive) 5.31 0.78 (19.63) EST3 (The app experience was pleasant) 5.18 0.79 (17.54) EST4 (I feel a real sense of harmony) 5.14 0.76 (16.40)

BI 5.40 0.90 0.92

BI1 (I will continue to use) 5.36 0.81 (n/a)

BI2 (I will recommend others to use) 5.40 0.92 (22.66)

BI3 (I will use in the future) 5.43 0.88 (21.15)

aItems were rated on a seven-point Likert scale for each item. b

All tests were significant at p < 0.001.

Note: Satorra-Bentlerχ2 = 574.68, P < 0.01, Non-Normed Fit Index = 0.934, Comparative Fit Index = 0.944, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.063, Bollen’s (IFI) Fit Index = 0 .943, 90% Confidence Interval of RMSEA = (0.057, 0.069).

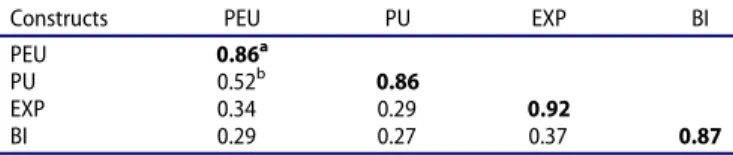

The discriminant validity is assessed by comparing the square roots of each average variance extracted (AVE) to the corresponding correlation estimate among the latent constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As shown in Table 4, the square roots of each AVE exceeded the corresponding correlation estimates among the constructs, implying adequate discriminant validity. Following Woosnam (2011), maximal weighted alphas, a robust estimate of internal consistency, was used to examine the internal consistency of the scale. As shown in Table 3, the latent constructs demonstrated a good internal consistency with maximal weighted alphas was in excess of the 0.70 critical values. Composite reliability was also used to assess the scale reliability, and the alpha critical value of 0.7 was suggested (Bagozzi & Yi, 1988; Lance, Butts, & Michels, 2006). As displayed in Table 3, all scales in the current study had an alpha critical value of 0.8, indicating that scale reliability was considered appropriate as it exceeds the corresponding threshold values for each of the factors analyzed.

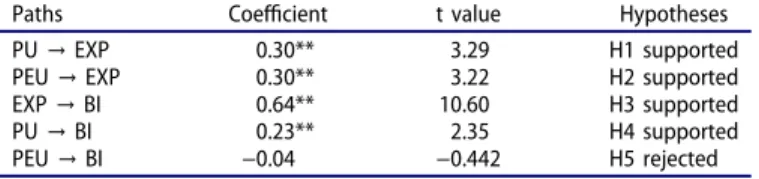

As Kline (2005) claims, once the measurement model demonstrates an acceptable fit with appropriate goodness fit indices implying the scales are reliable and valid, the proposed conceptual paths can be examined by the structural model. Further, a structural model was conducted to examine the relationship among the research con-structs by assessing all the path coefficients and squared multiple correlations. The structural model demonstrated an acceptable fit with S-B χ2 = 579, p < 0.01, Non-Normed Fit Index = 0.934, Comparative Fit Index = 0.943, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.063, Bollen’s (IFI) Fit Index = 0 .943, and 90% Confidence Interval of RMSEA = (0.057, 0.069). As displayed inFigure 2, four structural regression coefficients out of five proposed in the conceptual model were statistically significant. An examination of path estimates revealed that perceived usefulness (β = .30, p < .05) was a significant predictor of hotel consumer experience with mobile apps, providing support for hypothesis 1. Moreover, significant direct effects of perceived ease of use on the hotel consumer’s experience of the mobile app was observed (β = .30, p < .05). Hypothesis 2 is supported. The conceptual model of technology acceptance model provided a detailed account of the key forces underlying judgments of hotel consumer experience of mobile apps, explaining up to 32.5% of the variance in the important driver of consumer experience of mobile apps.

In addition, the results of this study indicated that a direct relationship exists between hotel consumer experience of mobile apps and behavioral intentions to use mobile apps (β = .64, p < .05), providing support for hypothesis 3. Furthermore, perceived usefulness has a positive and significant direct effect on hotel consumers’ behavioral intention to use

Table 4. Constructs inter-correlations and Average Variance Extracted (AVE).

Constructs PEU PU EXP BI

PEU 0.86a

PU 0.52b 0.86

EXP 0.34 0.29 0.92

BI 0.29 0.27 0.37 0.87

PU: Perceived usefulness, PEU: Perceived ease of use, EDU: education, ENT: entertainment, ESC: escapist, EST: esthetics, BI: behavioral intentions. aThe diagonal elements are the square root of the average variance extracted

(the shared variance between the factors and their measures). bThe off-diagonal elements are the correlations between factors.

a mobile app (β = .23, p < .05). Thus, hypothesis 4 is supported. The fifth hypothesis stated that the hotel consumer’s perceived ease of use of mobile app has a significant direct effect on behavioral intention. The results revealed that perceived ease of use did not have a significant effect on behavioral intentions (β = −0.04, p > .05); thus hypothesis 5 is not supported. Past studies regarding TAM document inconsistent results with respect to the relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions (Tao, 2009; Yuan, Liu, Yao, & Liu, 2016). Several scholars could not validate the relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions, indicating that in certain technological contexts perceived usefulness is a more important determinant influencing an individual’s adoption of technology (Koufaris,2002; Nysveen, Pedersen, & Thorbjørnsen,2005; Van der Heijden, Verhagen, & Creemers, 2003). Examining the squared multiple correlations in the structural model, the results revealed that perceived usefulness, ease of use, and experience together explained 56.7% of the variability in behavioral intentions to use hotel mobile apps.Table 5presents the results of hypotheses testing.

This study further examined whether the constructs of experience would mediate the relationship between technology factors and behavioral intentions. Following Sobel’s (1982) approach, the Sobel test was applied to examine the mediating effect of experience on the association between perceived usefulness and behavioral intentions. As suggested by Holbert and Stephenson (2003), the Sobel test of product-of-coefficient method, one of most widely used in social science with conservative statistical power and Type I error, was used to confirm the significance of mediating effects. According to MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, and Sheets (2002), the product of paths involving perceived usefulness and behavioral intentions, as well as consumer experience and behavioral

Figure 2.Structural model of testing the proposed hypotheses.

**t-tests were significant at p < 0.05.——Dash line indicates insignificant path. Presented are standar-dized coefficients. Note: Satorra-Bentler χ2 = 572.86, P < 0.01, Non-Normed Fit Index = 0.934, Comparative Fit Index = 0.943, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation = 0.063, Bollen’s (IFI) Fit Index = 0 .943, 90% Confidence Interval of RMSEA = (0.057, 0.069).

intention, along with associated standard error, was used to determine the significance of the mediating effect. The result of the Sobel test reveals that the absolute z-value for the mediating effect of experience on the link between perceived usefulness and behavioral intentions is greater than 1.96 (B product-of-coefficients = 0.19, Sobel Z = 3.79), suggest-ing the presence of a significant mediatsuggest-ing effect. Moreover, the direct relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions was not found to be a significant predictor of behavioral intentions. No further testing was required to determine whether the experience mediates the relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions.

Conclusions

The use of internet technology, such as smartphone apps, offers an opportunity for travelers to search for travel information, make connections with others, and make travel decisions more conveniently and cost-effectively (Arsal, Woosnam, Baldwin, & Backman,

2010). Recognizing the importance of mobile technology in hospitality and tourism (Wang, Xiang, & Fesenmaier, 2014), this study extends TAM, the dominant research model for studying technology acceptance, by incorporating the experience economy construct in understanding hotel consumer mobile app experience. The findings of this study suggest that the determinants of hotel consumer behavioral intentions with mobile apps are not only driven by cognitive beliefs, but also related to consumer experience. It could be argued that the design and features of mobile apps are critical in order to provide hotel consumers with an informational, enjoyable and immersive experience, conse-quently affecting their usage of mobile apps.

Discussion

The results of this study validate the research frameworks of TAM in the context of hotel consumer usage of mobile apps. Thefindings of this study provide empirical evidence for the proposed model and show that perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness have a positive impact on the hotel consumer experience of mobile apps. Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Kim, 2016; Mo Kwon et al., 2013; Morosan & DeFranco, 2016; Yang, 2017), the results of our research highlight the importance of perceived usefulness in determining behavioral intentions regarding mobile apps usage, suggesting that in order to increase customers’ hotel app acceptance and behavioral intentions, hospitality business operators should enhance the functional aspect of the mobile apps. The results of

Table 5.The result of hypotheses testing.

Paths Coefficient t value Hypotheses

PU→ EXP 0.30** 3.29 H1 supported

PEU→ EXP 0.30** 3.22 H2 supported

EXP→ BI 0.64** 10.60 H3 supported

PU→ BI 0.23** 2.35 H4 supported

PEU→ BI −0.04 −0.442 H5 rejected

**t-tests were significant at p < 0.05.

PU: Perceived usefulness, PEU: Perceived ease of use, EDU: education, ENT: entertainment, ESC: escapist, EST: esthetics, BI: behavioral intentions.

this study show that perceived ease of use does not drive the hotel consumers’ behavioral intentions, an outcome that contradicts the works of Kim, Park, et al. (2008) and Mallat, Rossi, Tuunainen, and Öörni (2009) in mobile technology contexts. This results suggest that due to the increase use of mobile devices and the nature of tasks, user-friendly feature of mobile apps are not a significant determinate for behavioral intention.

The results of this study indicate that perceived ease of use and usefulness play an important role in determining hotel consumers’ experience of mobile apps. Indeed, this study confirms findings from prior research (Lee, Chung, & Jung,2015; Pallud & Straub,

2014; Sheng & Teo,2012) that perceived utilitarian interface of hotel mobile apps as easy to use and effective in trip planning are shown to be direct antecedents of consumer experience. Moreover, the results of this study provide empirical support for the idea that hotel consumers who have a positive experience with mobile apps develop an interest in sharing the hotel apps experience and recommending the apps to others, which is consistent with prior studies by Jeng, Pai, and Yeh (2017), and Mohseni, Jayashree, Rezaei, Kasim, and Okumus (2018).

The results of this study also confirm that the consumer experience of mobile apps mediate the relationship between perceived usefulness and behavioral intentions, similar to findings by Sheng and Teo (2012) and Chung and Kwon (2009), implying that the perception of usefulness leads to a positive consumer experience, which in turn impacts behavioral intentions to use mobile apps. However, the results of the mediating effect on the relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions contradict the findings of prior research by Verhagen et al. (2011), which indicate that consumer experience has been found to have a mediating influence upon the link between perceived ease of use and behavioral intentions.

Theoretical contribution

As Morosan and DeFranco (2016) suggested, while mobile technology becomes an increasingly fruitful arena for research, the sporadic research focusing on hotel con-sumer mobile commerce has not been able to sufficiently explain the critical issues of mobile app experience within a hospitality and tourism context. This study proposed a holistic model of customers’ experiences to their usage of hotel mobile apps and provided evidence for identifying the important factors that enhance customers’ engagement behaviors in the context of hotel mobile application. The findings of the current study suggest that the experience economy construct is relevant within the mobile technology context and significant in influencing consumer behavioral inten-tions toward mobile apps usage. Additionally, the effect of perceived ease of use and usefulness on consumer behavioral intentions is indirect, as mediated by the experience economy construct.

By drawing on prior research on extensions of TAM in related contexts (e.g., Ozturk et al., 2016), this study extends the understanding of the experience economy perspective specifically in the context of mobile apps, and particularly in hospitality and tourism literature. Most importantly, to ground the examination of consumer behavior in mobile commerce within the theoretical framework of TAM (Davis, 1989), this study extends the belief-behavior approach to incorporate the experience economy aspects that influence hotel consumer technology use, thus advancing the general TAM extension literature. With few

studies examining how behavioral intentions toward usage of mobile apps are influenced in a hotel mobile service context, this study serves as a foundation by providing an insightful understanding of hotel mobile apps to a platform for both consumers and firms.

Managerial implications

Mobile technology has become a predominant distribution channel for the hotel industry in transforming the consumer experience (Ozturk, Bilgihan, et al., 2016). From the standpoint of hospitality and tourism marketing, the experiential aspect of technology use is an important construct for understanding hotel consumer behavior, which clearly shows the importance of interfacing within mobile app applications for hotel marketing managers and application developers alike. Further, the perceived ease of usefulness via experience has positively impacted hotel consumer behavioral inten-tions. Therefore, hospitality marketers and application developers should design more informative, enjoyable, and immersive app experiences for hotel consumers (tom Dieck et al., 2018). The findings of the study are important for hospitality managers and application designers from various disciplines that concern creating enjoyable, educa-tional and immersive experiences through interaction with mobile apps. To create an enjoyable mobile app experience, hotels should apply various designs, such as color, photographs, animation and music that makes the mobile app experience attractive and pleasant (Page, 2013). Additionally, a hotel mobile app should be informative about functionality and quality of hotel services as well as tourism information customers may potentially needed (Tarute, Nikou, & Gatautis, 2017). Moreover, devel-oping interactive functions such as online bidding and sharing to social media (Facebook or Instagram) may contribute to marketing exposure (Adukaite et al.,

2013). The previous ideas lead to positive customers’ evaluations and benefit the hotel business. Moreover, the results on user perception of mobile apps show that hotel consumers stress the importance of ease of use and usefulness, which could provide timely and relevant information in terms of mobile app design and functional features (Wang et al., 2016).

Limitations

The exploratory nature of the study collected a small sample and hence the results may not be able to be generalized to other mobile phone technologies and therefore more diverse populations could be looked at in the future. Additionally, the present study is limited to investigating the uni-dimension of four realms of experience economy affecting hotel consumers’ mobile app usage. Per Loureiro’s (2014) suggestion, the proposed model may be replicated using data gathered in different types of experiences by comparing the contexts of the more passive nature of entertainment and esthetics with the experience of active participation of education and escapism. Moreover, according to Morosan and DeFranco (2016), as new business applications continue to develop, it is suggested that future studies could employ the experimental approaches in obtaining an evaluation of hotel consumer technology experience in different mobile technologies such as wearable technologies. Additionally, the current study focused on hotel consumer mobile app experience from the experience economy point-of-view, and further research could

combine with other hedonic experiential factors such as consumer emotion (Jeong et al.,

2009) and perceived values (Ozturk, Nusair, et al., 2016) to provide deeper insights in understanding the mechanisms that drive hotel consumer reaction to mobile technology. Funding

This study was conducted with the support of the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan under research grant MOST103-2410-H-020-012;Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan [MOST103-2410-H-020-012];

ORCID

Chia-Pin Yu http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7099-4026

References

Adukaite, A., Reimann, A. M., Marchiori, E., & Cantoni, L. (2013). Hotel mobile apps. The case of 4 and 5 star hotels in European German-speaking countries. In Z. Xiang & L. Cantoni (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014 (pp. 45–57). Berlin, Heidelberg, Germany: Springer International Publishing.

Agag, G., & El-Masry, A. A. (2016). Understanding consumer intention to participate in online travel community and effects on consumer intention to purchase travel online and WOM: An integration of innovation diffusion theory and TAM with trust. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 97–111. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.038

Agrebi, S., & Jallais, J. (2015). Explain the intention to use smartphones for mobile shopping. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 22, 16–23. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2014.09.003 Ahlan, A. R., & Ahmad, B. I. E. (2015). An overview of patient acceptance of Health Information

Technology in developing countries: A review and conceptual model. International Journal of Information Systems and Project Management, 3(1), 29–48.

Ajzen, I., & Driver, B. L. (1992). Application of the theory of planned behavior to leisure choice. Journal of Leisure Research, 24(3), 207–224. doi:10.1080/00222216.1992.11969889

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Andersson, T. D. (2007). The tourist in the experience economy. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 46–58. doi:10.1080/15022250701224035

Arsal, I., Woosnam, K. M., Baldwin, E. D., & Backman, S. J. (2010). Residents as travel destination information providers: An online community perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 49(4), 400–413. doi:10.1177/0047287509346856

Ashraf, A. R., Thongpapanl, N., & Auh, S. (2014). The application of the technology acceptance model under different cultural contexts: The case of online shopping adoption. Journal of International Marketing, 22(3), 68–93. doi:10.1509/jim.14.0065

Ayeh, J. K. (2015). Travellers’ acceptance of consumer-generated media: An integrated model of technology acceptance and source credibility theories. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 173–180. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.049

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327

Baptista, G., & Oliveira, T. (2015). Understanding mobile banking: The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology combined with cultural moderators. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 418–430. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.024

Bentler, P. M., & Hu, L. T. (1995). Evaluating model fit. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications, 76–99.

Bigné, J. E., Andreu, L., & Gnoth, J. (2005). The theme park experience: An analysis of pleasure,

arousal and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 26(6), 833–844. doi:10.1016/j.

tourman.2004.05.006

Bilgihan, A., Nusair, K., Okumus, F., & Cobanoglu, C. (2015). Applying flow theory to booking experiences: An integrated model in an online service context. Information & Management, 52 (6), 668–678. doi:10.1016/j.im.2015.05.005

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2015). Business research methods. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Buhalis, D., & Amaranggana, A. (2015). Smart tourism destinations enhancing tourism experience

through personalisation of services. In I. Tussyadiah & A. Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015 (pp. 377–389). Switzerland: Springer.

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL. Prelis, and Simplis (pp. 196–199). New York: Psychology Press.

Castañeda, J. A., Muñoz-Leiva, F., & Luque, T. (2007). Web Acceptance Model (WAM): Moderating effects of user experience. Information & Management, 44(4), 384–396. doi:10.1016/j.im.2007.02.003

Chen, M. M., Murphy, H. C., & Knecht, S. (2016). An importance performance analysis of smartphone applications for hotel chains. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 29, 69–79. doi:10.1016/j.jhtm.2016.05.001

Cheung, R., & Vogel, D. (2013). Predicting user acceptance of collaborative technologies: An extension of the technology acceptance model for e-learning. Computers & Education, 63, 160–175. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.12.003

Childers, T. L., Carr, C. L., Peck, J., & Carson, S. (2001). Hedonic and utilitarian motivations for online retail shopping behavior. Journal of Retailing, 77(4), 511–535. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00056-2 Chung, N., & Kwon, S. J. (2009). The effects of customers’ mobile experience and technical support

on the intention to use mobile banking. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(5), 539–543. doi:10.1089/cpb.2009.0014

Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. doi:10.2307/249008

Davis, N. (2003). Technology in Teacher Education in the USA: What makes for sustainable good practice? Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 12(1), 59–84. doi:10.1080/14759390300200146 Dickinson, J. E., Ghali, K., Cherrett, T., Speed, C., Davies, N., & Norgate, S. (2014). Tourism and the

smartphone app: Capabilities, emerging practice and scope in the travel domain. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(1), 84–101. doi:10.1080/13683500.2012.718323

Dogruel, L., Joeckel, S., & Bowman, N. D. (2015). The use and acceptance of new media entertainment technology by elderly users: Development of an expanded technology accep-tance model. Behaviour & Information Technology, 34(11), 1052–1063. doi:10.1080/ 0144929X.2015.1077890

Dube, A., & Helkkula, A. (2015). Service experiences beyond the direct use: Indirect customer use experiences of smartphone apps. Journal of Service Management, 26(2), 224–248. doi:10.1108/ JOSM-11-2014-0308

Eden, H., & Gretzel, U. (2012). A taxonomy of mobile applications in tourism. E-Review of Tourism Research, 10(2), 47–50.

Escobar-Rodríguez, T., & Carvajal-Trujillo, E. (2014). Online purchasing tickets for low cost carriers: An application of the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) model. Tourism Management, 43, 70–88. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2014.01.017

Fetscherin, M., & Lattemann, C. (2008). User acceptance of virtual worlds. Journal of Electronic Commerce Research, 9(3), 231–242.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 382–388. doi:10.1177/ 002224378101800313

Gamal Aboelmaged, M. (2010). Predicting e-procurement adoption in a developing country: An empirical integration of technology acceptance model and theory of planned behaviour. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 110(3), 392–414. doi:10.1108/02635571011030042 Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An

integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. doi:10.2307/30036519

Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (1997). Gender differences in the perception and use of e-mail: An extension to the technology acceptance model. MIS Quarterly, 389–400. doi:10.2307/249720 Gilmore, J. H., & Pine, B. J. (2002). Differentiating hospitality operations via experiences: Why

selling services is not enough. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 43(3), 87–96. doi:10.1016/S0010-8804(02)80022-2

Gretzel, U., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2003). Experience-based internet marketing: An exploratory study of sensory experiences associated with pleasure travel to the Midwest United States. In: A. Frew, M. Hitz, & P. O'Connor (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism. ENTER2003 (pp. 49-57). New York: Springer-Verlag.

Hair, J. F., Jr, Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1995). Multiple discriminant analysis, Multivariate data analysis, 178–256.

Hausman, A. V., & Siekpe, J. S. (2009). The effect of web interface features on consumer online purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 62(1), 5–13. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.018 Holbert, R. L., & Stephenson, M. T. (2003). The importance of indirect effects in media effects

research: Testing for mediation in structural equation modeling. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47(4), 556–572. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem4704_5

Hosany, S., & Witham, M. (2010). Dimensions of cruisers’ experiences, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. Journal of Travel Research, 49(3), 351–364. doi:10.1177/0047287509346859 Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage. Hsiao, C. H., Chang, J. J., & Tang, K. Y. (2016). Exploring the influential factors in continuance

usage of mobile social Apps: Satisfaction, habit, and customer value perspectives. Telematics and Informatics, 33(2), 342–355.

Huang, Y. C., Backman, K. F., Backman, S. J., & Chang, L. L. (2016). Exploring the implications of virtual reality technology in tourism marketing: An integrated research framework. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(2), 116–128. doi:10.1002/jtr.v18.2

Hwang, J., & Lyu, S. O. (2015). The antecedents and consequences of well-being perception: An application of the experience economy to golf tournament tourists. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 4(4), 248–257. doi:10.1016/j.jdmm.2015.09.002

Jeng, M. Y., Pai, F. Y., & Yeh, T. M. (2017). The virtual reality leisure activities experience on elderly people. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12(1), 49–65. doi:10.1007/s11482-016-9452-0 Jeong, W. J., Fiore, A. M., Niehm, L. S., & Lorenz, F. O. (2009). The role of experiential value in

online shopping: The impacts of product presentation on consumer responses towards an apparel web site. Internet Research, 19(1), 105–124. doi:10.1108/10662240910927858

Joo, J., & Sang, Y. (2013). Exploring Koreans’ smartphone usage: An integrated model of the technology acceptance model and uses and gratifications theory. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2512–2518. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2013.06.002

Jung, T., tom Dieck, M. C., Lee, H., & Chung, N. (2016). Effects of virtual reality and augmented reality on visitor experiences in museum. In A. Inversini & R. Schegg (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2016 (pp. 621–635). Wien: Springer International. Jung, Y., Perez-Mira, B., & Wiley-Patton, S. (2009). Consumer adoption of mobile TV: Examining

psychological flow and media content. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(1), 123–129. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2008.07.011

Kang, M., & Schuett, M. A. (2013). Determinants of sharing travel experiences in social media. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 30(1–2), 93–107. doi:10.1080/10548408.2013.751237

Kaplanidou, K., & Vogt, C. (2006). A structural analysis of destination travel intentions as a function of web site features. Journal of Travel Research, 45(2), 204–216. doi:10.1177/ 0047287506291599

Kesharwani, A., & Singh Bisht, S. (2012). The impact of trust and perceived risk on internet banking adoption in India: An extension of technology acceptance model. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 30(4), 303–322. doi:10.1108/02652321211236923

Kim, D., & Adler, H. (2011). Students’ use of hotel mobile apps: Their effect on brand loyalty. Paper presented at the 16th Graduate Students Research Conference, Houston, TX.

Kim, D.-Y., Park, J., & Morrison, A. M. (2008). A model of traveller acceptance of mobile technology. International Journal of Tourism Research, 10(5), 393–407. doi:10.1002/jtr.v10:5 Kim, J. (2016). An extended technology acceptance model in behavioral intention toward hotel

tablet apps with moderating effects of gender and age. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(8), 1535–1553. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-06-2015-0289

Kim, K. H. (2012). Smartphone application effecting potential increase of hotel business revenue and guest satisfaction (Master thesis). University of Nevada, Las Vegas, Nevada. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-11-11-0999-PDN

Kim, T. G., Lee, J. H., & Law, R. (2008). An empirical examination of the acceptance behaviour of hotel front office systems: An extended technology acceptance model. Tourism Management, 29 (3), 500–513. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.05.016

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Koufaris, M. (2002). Applying the technology acceptance model andflow theory to online consumer behavior. Information Systems Research, 13(2), 205–223. doi:10.1287/isre.13.2.205.83

Lam, T., Cho, V., & Qu, H. (2007). A study of hotel employee behavioral intentions towards adoption of information technology. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 26(1), 49–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2005.09.002

Lance, C. E., Butts, M. M., & Michels, L. C. (2006). The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria what did they really say? Organizational Research Methods, 9(2), 202–220. doi:10.1177/ 1094428105284919

Lee, H., Chung, N., & Jung, T. (2015). Examining the cultural differences in acceptance of mobile augmented reality: Comparison of South Korea and Ireland. In I. Tussyadiah & A. Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism (pp. 477–491). Heidelberg: Springer.

Lee, K., Lee, H. R., & Ham, S. (2013). The effects of presence induced by smartphone applications on tourism: Application to cultural heritage attractions. In X. Xiang & I. Tussyadiah (Eds), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2014 (pp. 59–72). Vienna: Springer. Lee, S., Bruwer, J., & Song, H. (2017). Experiential and involvement effects on the Korean wine

tourist’s decision-making process. Current Issues in Tourism, 20(12), 1215–1231. doi:10.1080/ 13683500.2015.1050362

Lee, S., & Jeong, M. (2012). Effects of e-servicescape on consumers’ flow experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 3(1), 47–59. doi:10.1108/17579881211206534

Lee, S. A. (2018). M-servicescape: Effects of the hotel mobile app servicescape preferences on customer response. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 9(2), 172–187. doi:10.1108/ JHTT-08-2017-0066

Lee, W., Xiong, L., & Hu, C. (2012). The effect of Facebook users’ arousal and valence on intention to go to the festival: Applying an extension of the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 819–827. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.09.018

Lee, Y. H., Hsieh, Y. C., & Hsu, C. N. (2011). Adding innovation diffusion theory to the technology acceptance model: Supporting employees’ intentions to use e-learning systems. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 14, 4.

Li, M., Dong, Z. Y., & Chen, X. (2012). Factors influencing consumption experience of mobile commerce: A study from experiential view. Internet Research, 22(2), 120–141. doi:10.1108/ 10662241211214539

Liu, X., Huang, D., & Li, Z. (2018). Examining relationships among perceived benefit, tourist experience and satisfaction: The context of intelligent sharing bicycle. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(5), 437–449. doi:10.1080/10941665.2018.1466814

Liu, Y., Li, K. J., Chen, H., & Balachander, S. (2017). The effects of products’ aesthetic design on demand and marketing-mix effectiveness: The role of segment proto-typicality and Brand con-sistency. Journal of Marketing, 81(1), 83–102. doi:10.1509/jm.15.0315

Liu, Y., Pu, B., Guan, Z., & Yang, Q. (2016). Online customer experience and its relationship to repurchase intention: An empirical case of online travel agencies in China. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(10), 1085–1099. doi:10.1080/10941665.2015.1094495

Loureiro, S. M. C. (2014). The role of the rural tourism experience economy in place attachment and behavioral intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 40, 1–9. doi:10.1016/ j.ijhm.2014.02.010

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83

Mallat, N., Rossi, M., Tuunainen, V. K., & Öörni, A. (2009). The impact of use context on mobile services acceptance: The case of mobile ticketing. Information & Management, 46(3), 190–195. doi:10.1016/j.im.2008.11.008

Manthiou, A., Lee, S., Tang, L., & Chiang, L. (2014). The experience economy approach to festival marketing: Vivid memory and attendee loyalty. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(1), 22–35. doi:10.1108/JSM-06-2012-0105

Mathwick, C., Malhotra, N., & Rigdon, E. (2001). Experiential value: Conceptualization, measure-ment and application in the catalog and Internet shopping environmeasure-ment. Journal of Retailing, 77 (1), 39–56. doi:10.1016/S0022-4359(00)00045-2

McLellan, H. (1999). Online education as interactive experience: Some guiding models. Educational Technology, 39(5), 36–42.

Mehmetoglu, M., & Engen, M. (2011). Pine and Gilmore’s concept of experience economy and its dimensions: An empirical examination in tourism. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 12(4), 237–255. doi:10.1080/1528008X.2011.541847

Mo Kwon, J., Bae, J. I., & Blum, S. C. (2013). Mobile applications in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology, 4(1), 81–92. doi:10.1108/17579881311302365

Mohseni, S., Jayashree, S., Rezaei, S., Kasim, A., & Okumus, F. (2018). Attracting tourists to travel companies’ websites: The structural relationship between website brand, personal value, shopping experience, perceived risk and purchase intention. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(6), 616–645. doi:10.1080/13683500.2016.1200539

Morgan-Thomas, A., & Veloutsou, C. (2013). Beyond technology acceptance: Brand relationships and online brand experience. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 21–27. doi:10.1016/j. jbusres.2011.07.019

Morosan, C. (2010). Theoretical and empirical considerations of guests’ perceptions of biometric systems in hotels: Extending the technology acceptance model. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 36(1), 52–84. doi:10.1177/1096348010380601

Morosan, C. (2011). Customers’ adoption of biometric systems in restaurants: An extension of the technology acceptance model. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 20(6), 661–690. doi:10.1080/19368623.2011.570645

Morosan, C., & DeFranco, A. (2015). Disclosing personal information via hotel apps: A privacy calculus perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 120–130. doi:10.1016/j. ijhm.2015.03.008

Morosan, C., & DeFranco, A. (2016). Modeling guests’ intentions to use mobile apps in hotels: The roles of personalization, privacy, and involvement. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(9), 1968–1991. doi:10.1108/IJCHM-07-2015-0349

Muñoz-Leiva, F., Climent-Climent, S., & Liébana-Cabanillas, F. (2017). Determinants of intention to use the mobile banking apps: An extension of the classic TAM model. Spanish Journal of Marketing-ESIC, 21(1), 25–38. doi:10.1016/j.sjme.2016.12.001