客語母語者使用國音/ɕ/的狀況:社會語言學分析 - 政大學術集成

118

0

0

全文

(2) Acknowledgements. 辛苦了四年終於要從語言所畢業了,首先要感謝詹惠珍老師的教導,讓我能夠 順利地完成論文,在老師身上學到許多社會語言學中寶貴的知識以及經驗。也要 特別感謝我的口試委員曹逢甫教授,陳振寬教授以及蘇席瑤教授珍貴的意見。除 此之外,感謝所上的同學讓自己能夠在學業上互相學習,能夠認識你們真好! 還要感謝所有參與訪談的受試者們撥出你們寶貴的時間,尤其要特別感謝我 大學的學長冠中以及陳美榮老師的協助,如果沒有你們的幫忙真的不知道要去哪 裡找桃園市的受試者,真的很感謝你們的幫忙。. 政 治 大. 最後,我要感謝我的父母以及遠在德國的妹妹。在寫論文的過程中有你們的. 立. 陪伴以及鼓勵讓我能夠完成學業,也讓我一路上不感到孤單。真的謝謝你們的支. ‧ 國. 學. 持,謹將這本論文獻給我最愛的家人。. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i. i n U. v.

(3) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….i Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...……ii List of Maps…………………………………………………………………………..vi List of Tables…………………………………………………………………………vii Abstract………………………………………………………………………………..x Chapter 1 Introduction………………………………………………………………1 1.1 Rationale………………………………………………………………………...1 1.2 Linguistic and Social-Historical Backgrounds………………………………….1 1.3 Geographical Backgrounds……………………………………………………..2 1.3.1 Geographical location……………………………………………………..2 1.3.2 Demographic backgrounds………………………………………………..4 1.3.3 Socio-economic of the two cities…………………………………………5 1.4 Research Questions and Hypotheses……………………………………………5. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. sit. y. Nat. Chapter 2 Literature Review………………………………………………………...7 2.1 Theories of Linguistic Variation and Change…………………………………...7. n. al. er. io. 2.1.1 The formalism’s point of view……………………………………………7 2.1.2 Lexical diffusion theory…………………………………………………..9 2.1.3 Sociolinguistic variation…………………………………………………10 2.2 Linguistic Variation within Context…………………………………………...10 2.2.1 Speech community………………………………………………………10 2.2.2 Language contact………………………………………………………...11 2.2.3 External factors of linguistic variation…………………………………..12 2.2.3.1 linguistic variation by geography……………………………….12 2.2.3.2 linguistic variation by formality………………………………...13 2.3.3.3 linguistic variation by social space……………………………...14 2.2.4 Language attitudes……………………………………………………….17. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Chapter 3 Methodology…………………………………………………………….19 3.1 Design of Quantitative Analysis……………………………………………….19 3.1.1 Linguistic factors………………………………………………………...19 3.1.1.1 neighboring sounds………………………………………………19 ii.

(4) 3.1.1.2 syllable structures……………………………………………….....................20 3.1.1.3 character frequency………………………………………………21 3.1.2 Non-linguistic factors……………………………………………………23 3.1.2.1 situational formality……………………………………………...23 3.1.2.2 nature of the geographical area…………………………………..23 3.1.2.3 social factors……………………………………………………..23 3.2 The Tools……………………………………………………………………..24 3.2.1 Conversation……………………………………………………………24 3.2.2 Reading passages……………………………………………………….25 3.2.3 Reading characters……………………………………………………..25 3.3 Design of Qualitative Analysis……………………………………………….25 3.4 Measurement…………………………………………………………………26 3.5 Sampling……………………………………………………………………...26 3.5.1 Source of subjects………………………………………………………26 3.5.2 Social distributions of the subjects……………………………………..27 3.6 The Procedure of Data Collection……………………………………………28. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. ‧. Chapter 4 Data Analyses……………………………………………………………29 4.1 General distributions of the Two Variants of /ɕ/……………………………...29 4.1.1 Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by formality…………………...29 4.1.2 Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by social/geographical factors………………………………………………………………….30 4.1.3 Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by social/geographical factors and formality…………………………………………………..33 4.2 Distributions of [s]% by Syllable Structures………...................................... .35 4.2.1 General distributions of [s]% by syllable structures…………………...35 4.2.2 Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and formality…………….36 4.2.3 Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and social/geographical factors………………………………………………………………….37 4.2.4 Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures, formality, and social/geographical factors………………………………………..39 4.2.5 Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and interactions of social/geographical factors…….........................................................41 4.2.6 Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures, formality, and the interactions of social/geographical factors…………….........................43 4.3 Distributions of [s]% by the Advancement of the Preceding Vowels………..47 4.3.1 General distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels…………………………………......................47. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iii. i n U. v.

(5) 4.3.2 Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels and formality…………………………………………………………..48 4.3.3 Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels and social/geographical factors………………………………………..49 4.3.4 Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels, formality, and social/geographical factors……………………………..50 4.3.5 Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels and the interactions of the social/geographical factors………………..52 4.3.6 Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels, formality, and the interactions of the social/geographical factors..........56 4.4 Distributions of [s]% by the Preceding Nasals……………………………….63 4.4.1 General distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals…………………63 4.4.2 Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals and formality…………..63 4.4.3 Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals and social/geographical factors…………………………………………….64 4.4.4 Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals, formality and social/geographical factors formality………………………................ 66 4.4.5 Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals and the interactions of social/geographical factors……………………………………….... 67 4.4.6 Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals, formality ,and the interactions of social/geographical factors…………...............70 4.5 [s]% in Lexical Diffusison…………………………………………...............73 4.5.1 [s]% in lexical diffusion by character frequency and formality………………………......................................................73 4.5.2 [s]% in lexical diffusion by syllable structures and formality…………………………………………………………..74 4.5.3 [s]% in lexical diffusion by characters…………………………………75 4.6 Subjects’ Stereotypical Impressions toward Hakka Dialect………………….76 4.6.1 Subjects’ stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect with subjects as a whole……………………………………………….76 4.6.2 Subjects’ stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect by social/geographical factors…………………………………………77 4.6.3 [s]% by stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect, formality, and social/geographical factors………………………………………..79 4.6.4 The subjects’ stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect by the interactions of social/geographical factors……………………..81. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. iv. i n U. v.

(6) 4.7 [s]% by Subjects’ Proficiency in Hakka and Frequency of using Hakka.................................................................................................82 Chapter 5 Conclusions……………………………………………………………...85 5.1 Summary of the Major Findings………………..……..……………………..86 5.2 Conclusions…………………………………………………………………..86 5.3 Limitations………………………………………………………………..….87. References…………………………………………………………………………... 89 Appendices…………………………………………………………………………...94 Appendix 1: Topics for Conversation……………………………………………95 Appendix 2: Passages for Reading ……………………………………………..100 Appendix 3: Characters for Reading…………………………………………....101 Appendix 4: Stereotypical Impressions of Hakka Dialect………...……………102 Appendix 5: Questions for Interview…………………………………………...103. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. v. i n U. v.

(7) LIST OF MAPS Page Map 1: Distribution of Hakka people in Taiwan………………………………………3 Map 2: Locations of Taoyuan City and Chungli City in Taoyuan County…………. ..4. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vi. i n U. v.

(8) LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Syllable frames and syllable structures containing /ɕ/...................................21 Table 2. Syllable structures and character frequency of / ɕ/ in the survey...................22 Table 3. Social distributions of the subjects………………………………………….27 Table 4. General distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/……………………………..29 Table 5. Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by formality………………………..30. 政 治 大. Table 6. Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by social/geographical factors……………... ……………………………....31. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Table 7. Distributions of [s]% by social/geographical factors and formality………...34. ‧. Table 8. General distributions of [s]% by syllable structures………………………...36. sit. y. Nat. Table 9. Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and formality………………….36. n. al. er. io. Table 10. Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and social/geographical factors……………………………………………38. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Table 11. Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures, formality, and social/geographical factors………………………………. …………..40 Table 12. Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and the interactions of social factors…………………………………………………................42 Table 13. Distributions of [s]% in Conversation by syllable structures and the interactions of social/geographical factors………………………………...44 Table 14. Distributions of [s]% in Reading Passages by syllable structures and the interactions of social/geographical factors......................................45. vii.

(9) Table 15. Distributions of [s]% in Reading Characters by syllable structures and the interactions of social/geographical factors…………………..........46 Table 16. General distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels…………………………………………………………..47 Table 17. Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels and formality………………………………………………………………48 Table 18. Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels and social/geographical factors…………………………………............... 49 Table 19. Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels, formality, and social/geographical factors……………………………....... 51. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Table 20. Distributions of [s]% by the advancement of the preceding vowels and the interactions of social/geographical factors……………………......53. ‧. Table 21. Distributions of [s]% in Conversation by the advancement of the preceding vowels and the interactions of social/geographical factors………………. …………………………….57. sit. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. Table 22. Distributions of [s]% in Reading Passages by the advancement of the preceding vowels and the interactions of social/geographical factors……………………………………………...60. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Table 23. General distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals…………………….63 Table 24. Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals and formality……………...64 Table 25. Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals and social/geographical factors…………………………………………....65 Table 26. Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals, formality, and social/geographical factors…………………………………………....66 Table 27. Distributions of [s]% by the preceding nasals and the interactions of social/geographical factors………………………..68 viii.

(10) Table 28. Distributions of [s]% in Conversation by preceding nasals and the interactions of social/geographical factors……..............................71 Table 29. Distributions of [s]% in Reading Passages by preceding nasals and the interactions of social/geographical factors……..............................72 Table 30. [s]% in lexical diffusion by character frequency and formality...................73 Table 31. [s]% in lexical diffusion by syllable structures and formality……………..74 Table 32. [s]% in lexical diffusion by syllable structures, character frequency, characters, and formality…………………………………………………..75. 政 治 大. Table 33. Stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect by subjects as a whole….77. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Table 34. Stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect by social/geographical factors……………………………………………..78. ‧. Table 35. [s]% by stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect, formality, and social/ geographical factors…………………………………………...79. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. Table 36. The subjects’ stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect by the interactions of social/geographical factors………………………………...81. Ch. i n U. v. Table 37. [s]% by subjects’ stereotypical impressions toward Hakka dialect, proficiency in Hakka, and frequency of using Hakka……………………..83. engchi. ix.

(11) Abstract. Most Hakka speakers in Taiwan, if not all, speak Mandarin Chinese. Among them, many leave some traces of their Hakka background in their Mandarin pronunciation. This thesis aims at analyzing the linguistic, situational, geographical, and social causes of the emergence of [s] as a phonetic variant of /ɕ/ in Mandarin by Hakka speakers.. 政 治 大 locate the internal and the external constraints on the target phonetic variation. Those 立 In this study, both quantitative and qualitative analyses were conducted to. data for quantitative analyses were collected from the linguistic production by 32. ‧ 國. 學. native speakers of Hakka in casual conversation, reading passage, and reading. ‧. characters. Subjects of this study are equally distributed to two genders, two education. sit. y. Nat. levels, two age groups, and two geographical areas (namely, in Taoyuan City and. io. er. Chungli City, two cities in which a large proportion of Hakka speakers reside) . As for data for qualitative analyses collected from 29 of the 32 subjects of the quantitative. al. n. v i n C h design that were tests, only those parts of the qualitative implemented correctly were engchi U analyzed.. The major findings of this study are (1) among the internal factors, word frequency, preceding vowels, and syllable structure were found to be influential to the target phonetic variation; (2) the target phonetic variation does expands through lexical diffusion; and (3) among the external factors, age and geographical area are more influential than situational formality and gender, but the impact of education level is weak. General conclusion of this study include (1) this target phonetic variation is expanding gradually through linguistic, situational, and x.

(12) social/geographical spaces; and (2) both internal and external factors are effective, with external factors being more influential than internal factors.. Key words: phonetic variation, lexical diffusion, formality, Hakka dialect, sociolinguistic variation, ethnic identity. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xi. i n U. v.

(13) Chapter One Introduction. 1.1 Rationale Hakka, a minority dialect in Taiwan, threatened by the two major languages on the island (namely, Mandarin and Southern Min dialect), is rarely used in the society of Taiwan. Under the pressure of social discrimination, some native Hakka speakers. 政 治 大 Language Policy (國語政策), which compels all citizens of Taiwan learn and use 立 conceal their ethnic background and their mother tongue. Due to the National. Mandarin, most Hakka speakers, except those of old age, speak Mandarin fluently, but. ‧ 國. 學. leave trace of their Hakka background in their Mandarin. For example, it is noticed. ‧. that some Hakka people pronounce Mandarin /ɕ/ as [s].. sit. y. Nat. In this researcher’s preliminary observation, it seems that the phonetic. io. er. manifestation of Mandarin /ɕ/ as [s] happens in certain phonetic environments, in certain geographical locations, in certain situations, by Hakka speakers of certain. n. al. social backgrounds.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 1.2 Linguistic and Social-historical Backgrounds of Hakka Hakka people in Taiwan are descendents of those Hakka immigrants from Mainland of China in 17th century. Since the Nationalist Government retreated to Taiwan in 1949, Mandarin has become the national language, the language for instruction, and the language for mass media. Hakka, thus, is degraded and used only for intra-family and intra-ethnic group communication, and Hakka people over fifty years old were forced to be bilinguals of Mandarin and their mother tongue. Since 1.

(14) Hakka people’s social status is lower than that of the Mainlanders, Hakka people turn into a minority group, and Hakka dialect is degraded and rarely used in the society of Taiwan. Fortunately, in 2001, Hakka Affairs Councils was founded to preserve Hakka dialect and culture. Since then, stronger and stronger emphasis has been placed on reviving the vitality of Hakka dialect. For example, Hakka has been taught as a subject in elementary school. It seems that Hakka dialect is now protected, supported, and promoted by the government and the Hakka people in Taiwan.. 1.3 Geographical Backgrounds 1.3.1 Geographical location. 立. 政 治 大. In many studies (such as Bailey, 1993), it has been verified that linguistic. ‧ 國. 學. variation is linked with the characteristics of a geographical area. According to this. ‧. researcher’s observation, residents of two cities (namely, Taoyuan City and Chungli. sit. y. Nat. City) seem to act differently in using Mandarin; therefore, these two cities are thus. io. er. chosen for investigation.. Both Taoyuan City and Chungli City locate in Taoyuan County, one of the three. al. n. v i n major countries in which HakkaC people reside. Taoyuan h e n g c h i U County is located in the north 1. of Taiwan. Taoyuan City and Chungli City are the two major cities in Taoyuan County, with Taoyuan City being in the north of Taoyuan County, and Chungli City in the south. The location of Taoyuan County in Taiwan is given in Map 1. The locations of Taoyuan City and Chungli City in Taoyuan County are given in Map 2.. 1. The three major counties of Taiwan in which Hakka people congregate are Taoyuan County, Hsinchu County, and Miaoli County. 2.

(15) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Map 1: Distribution of Hakka people in Taiwan. 3.

(16) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 sit. n. al. er. io. 1.3.2. y. Nat. Map 2: Location of Taoyuan City and Chungli City in Taoyuan County. Demographic backgrounds. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. According to Taoyuan County Government’s survey in August, 2013, Taoyuan City is a city of 34.8046 square kilometers with 415,367 citizens. According to Hakka Affairs Council’s survey, 2010, 2 among the population of this city, 76,200 people (18.73%) are Hakka. As for Chungli City, it is a city of 76.52 square kilometers with 377,855 citizens. According to Hakka Affairs Council’s survey in 2010, about 56.99% (210,700) people of the population are Hakka. In other words, Chungli City has more Hakka people than Taoyuan City, and the proportion density of Hakka people is larger. 2. The latest survey of Hakka population in Taoyuan was done in 2010, and no update demographic information is available since then. 4.

(17) in Chungli City than in Taoyuan City. 1.3.3. Socio-economic characteristics of the two cities Taoyuan City is the administration center of Taoyuan County and a city of. commerce, while Chungli City is a city of manufacturing industry. In comparison, the former is more like a cosmopolitan city, in which more Mandarin and less Hakka are used; and the latter is more like a town, in which Hakka is expected to be used more frequently. In general, the two cities investigated in this study are different from each. 政 治 大. other in geographical area, population size, and socio-economic characteristics.. 立. 1.4 Research Questions and Hypotheses. ‧ 國. 學. To examine the target phonetic variation, the following research questions are. ‧. proposed.. sit. y. Nat. (1) Is this phonetic variation of /ɕ/ related to the phonetic environments, neighboring. io. er. sounds, and syllable structure?. (2) Is this phonetic variation of /ɕ/ related to lexical frequency?. al. n. v i n (3) Does this phonetic variationC expand through lexical h e n g c h i Udiffusion? (4) Is this phonetic variation of /ɕ/related to situational formality?. (5) Is this phonetic variation of /ɕ/ related to geographical characteristics? (6) Is this phonetic variation of /ɕ/ related to Hakka speakers’ social characteristics (specifically, gender, age, and education level) Responding to the research questions given above, the following hypotheses are proposed. (1) Phonetic environments (including syllable structures and neighboring sounds) would affect the surface realization of /ɕ/. (2) Lexical frequency is related to the surface realization of /ɕ/, with characters of 5.

(18) high frequency yielding more nonstandard form [s]. (3) Situational formality is influential to the surface realization of /ɕ/ to [s], with the use of [s] increasing as the formality decreasing, and vice versa. (4) Geographical characteristics are effective to the surface realization of /ɕ/ to [s], with people in Chungli City using more [s] than those in Taoyuan City. (5) Social factors (including, gender, age, and education level) are effective in the surface realization of /ɕ/ to [s], with Hakka people of older age, of male, of lower education level using more [s]’s than their counter groups.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 6. i n U. v.

(19) Chapter Two Literature Review. In this chapter, theories and previous studies related to the target linguistic variation of this study are reviewed.. 2.1 Theories of Linguistic Variation and Change. 政 治 大 The Neogrammarian school proposes that language change is regular, and sound 立. 2.1.1 The formalism’s point of view. change is limited to a particular speech community at a particular time. Focusing on. ‧ 國. 學. sound change, the Neogrammarians assume that it is observable that a given time in a. ‧. given region, all the words which have a certain phonetic feature are subject to the. sit. y. Nat. same change. Verner’s law, illustrates a historical sound change in the Proto-Germanic. io. er. language, a good illustration of such assumption; however, since it is hard to find extremely regular sound change, the school excludes sporadic changes, although. al. n. v i n Verner (1877) claims that there C must be a rule within the h e n g c h i U irregulatities.. Structuralists propose that linguistic features can be described in terms of. structures and systems. Originated from a Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure, in the early twentieth century, the following ideas came into every school of linguistics. First, langue and parole are differentiated. According to Saussure (1916), parole, which includes spoken and written language, is concrete; however, langue, which is underlying the surface structure, is abstract. To Saussure, langue is more important than parole. Second, Saussure takes synchronic study as more critical than diachronic. In synchronic study, one describes the state of the language, disregarding whatever 7.

(20) changes might be taking place; while in diachronic study, a language is studied from the point of view of its historical development. Third, Saussure distinguishes syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations, with the former referring to the relationships between constituents in a construction, and the latter being defined as a class of associative relations. Fourth, the theory considers phonemes as the central units of a sound system. It was claimed that native speakers would be more aware of those contrastive phonemes than those that are not. Structuralists did propose different views of sound change. They tried to explain. 政 治 大 However, the theory still can not fully explain how and why language change 立. the sound shifts from the structure of systems and the structural functions of language.. happens.. ‧ 國. 學. Noam Chomsky, a representative of the generativists, in his Syntactic Structures. ‧. (1957), proposes that all languages are rule-governed; therefore, human beings are. sit. y. Nat. able to learn these rules in finite number to produce infinite number of sentences.. io. er. According to Chomsky, it is such linguistic competence that would allow human to encode and to decode a message. In comparison with Structuralists, Generativists put. al. n. v i n Cintrospected, more emphasis on linguistic data Structuralist focused on actual h e n g cwhile hi U. linguistic data. Moreover, Generativists focus on underlying system of the rules; while Structuralists emphasize surface structure. Further, Generativists believe that all sound changes occur in grammar. Postal (1968:270), in describing the core idea of the Generativist viewpoint about sound change, indicates that in early time, Generativists think that all changes must be simplificatory, translating more complex to simpler and more economical grammars. McMahon (1994) in his book Understanding Language Change, points out some deficits of the Generativist’s theory. First, early Generativists did not consider the effects of change on the system of sounds in a language. Instead, 8.

(21) the Generativist give formal phonological rules, which reflect completed changes, but are not explanatory. Second, not all changes could be construed as simplificatory. Third, there is no entire idea about what would constitute simplification, a concept that is relative rather than absolute. Fourth, the characterization of all changes as simplificatory presumes a view of change as constantly creating ever simpler grammars. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to prove that languages, following this view point, must have been getting simpler gradually ever since language began. 2.1.2 Lexical diffusion theory. 政 治 大 lexical diffusion, indicating that a sound change would spread gradually through 立. Linguistic variation is not instantaneous. Wang (1969, 1977) propose a theory of. lexical items carrying the target sound related to the sound change. In other words, a. ‧ 國. 學. sound change may apply to some words initially, moves on to other words, and then. ‧. still others, until that sound change is accomplished. Also, according to Bailey (1973),. sit. y. Nat. linguistic variation and change does not proceed across the affected lexical items at a. io. er. uniform rate. To be specific, the initial and the ending stages of a change are slow, but in the intermediate stage, the change is rapid. Chambers and Trudgill (1998, as cited. al. n. v i n in Wardaugh 2002: 223), in theirCstudy in East Anglia U h e n g c h i and the East Midland of. England, find that the same sound change is complete in must and come, but hardly at all in uncle and hundred. Likewise, Hansen (2001, as cited in Wardaugh 2002: 225) supports lexical diffused sound change of French nasal vowels. Phonetic variation may be evoked by linguistic factors, such as syllable structure and word frequency. It has been noticed that not all lexical items containing a target sound involved in a certain phonetic variation would experience the variation at the same time, in the same rate. Most scholars considered that the most frequent words are easier to comply to sound change. Schuchardt (1928) claims that the frequency in 9.

(22) using individual words that plays such a prominent role in analogical formation is also of great importance for their phonetic transformation. Therefore, it is said that “Rarely used words drag behind; very frequently used ones hurry ahead.’’ The view point was supported by Leslau (1969), and Fidelholz (1975). However, Hooper (1976) found that it is infrequent verbs, not frequent ones, that are the most possible ones to change to the regular –ed paradigm in English. Similarly, Phillips (1981), in his research of glide deletion in Southern American English words, finds that high frequency words would not necessarily induce higher percentage of sound change.. 政 治 大 of the diffusion of the nonstandard variant [s] of Mandarin /ɕ/. 立. In this study, lexical diffusion theory is applied to examine the scope and the rate. 2.1.3 Sociolinguistic variation. ‧ 國. 學. One of the most important tasks in the field of sociolinguistics is the study of. ‧. linguistic variation and change within social context. Although Labov (1994) admits. sit. y. Nat. that lexical diffusion is a fundamental mechanism of sound change, he still claims that. io. er. internal variation and social motivations among speakers are the most important factors in linguistic variation and change. More detailed reviews are given below.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2.2 Linguistic Variation within Context 2.2.1 Speech community. In the realm of sociolinguistics, the criterion for a speech community is far beyond just sharing a linguistic code system. The definition of speech community is different researchers. Hudson (1996: 29) indicates that “our sociolinguistic world is not organized in terms of objective ‘speech communities,’ even though we like to think subjectively in terms of communities or social types such as “Londoner” and “American.” In Hudson’s opinion, there is no clear definition of speech community. Lyons (1970: 362) considered speech community as the congregation of the people 10.

(23) who use a given language (or dialect). Giles, Scherer, and Taylor (1979:351) consider speech markers as important devices to divide social categories such as age, sex, ethnicity, social class, and situation. Although there are other ways to discriminate social categories, speech markers are still critical to social organization. According to Labov (1972: 120-1), a speech community is not defined by any marked agreement in the use of language elements, so much as by participation in a set of shared norms; these norms may be observed in overt types of evaluative behavior and by the uniformity of abstract. 政 治 大 Labov’s viewpoint to speech community focused on individuals’ feelings of being 立 patterns of variation which are invariant in respect to particular levels of usage.. members in the same community. Gumperz (1971: 101), using the concept of. ‧ 國. 學. linguistic community, instead of speech community, suggests that a speech. ‧. community can be either monolingual or multilingual, and speech community have to. sit. y. Nat. be independent in order to compare to other communities. Gumperz (1971: 114). io. er. provides another explanation of speech community, indicating that a community and the related language systems are not two independent entities, and that members in a. al. n. v i n speech community would have C something in common,Uincluding grammatical rules, hengchi. language use, and social norms. Following the definition given above, Taoyuan City and Chungli City are presumed to be two speech communities, with each having its own sociolinguistic norms for their choices between [ɕ] and [s]. 2.2.2 Language contact Very often people in the same geographical or social space speak more than one language (or dialect). Language contact is, hence, induced. According to Weinreich (1953), languages in contact would interfere each other: “Those instances of deviation from the norms of either language which occur in the speech of bilinguals as a result 11.

(24) of their familiarity with more than one language, i.e. as a result of language contact, will be referred to as interference phenomena." (Weinreich, 1953:56) For example, some Dutch would pronounce ‘finger’ /ˈfɪŋgə/ as [ˈfɪŋə] under the influence of the word ‘Vinger’ /ˈv̥ɪŋəʀ/ from Dutch. Weinreich (1953) also suggests that social factors should be taken into consideration, so that the situation of language contact could clearly be observed. Thomason and Kaufman (1988) include social factors in the theory, and they propose the importance of distinguishing borrowing and substratum interference, with the. 政 治 大 language,” and the latter referring to native language structures’ affecting the second 立 former referring to “ the incorporation of foreign elements into the speakers’ native. language (1988: 21).. ‧ 國. 學. Tse (1983) points out that most speakers in Taiwan are bilingual of Mandarin. ‧. Chinese and Southern Min dialect. Hakka people in Taiwan are even forced to be. sit. y. Nat. multilinguals of Mandarin, Southern Min dialect, and Hakka dialect, with Mandarin. io. er. being used in formal occasions, and Southern-Min and Hakka in less formal or casual occasions. In this study, it is curious that the emergence of the phonetic variant [s] of. al. n. v i n Mandarin /ɕ/ by Hakka people isCa consequence of language h e n g c h i U contact with Hakka being the source language and Mandarin being the target language.. 2.2.3 External factors of linguistic variation 2.2.3.1 linguistic variation by geography Space is an essential element in analyzing linguistic variation and change. It is expected that different geographical regions would have dialectal differences. Schmidt (1872), proposes “wave model” to explain linguistic variation, indicating that linguistic variation initiated in a region would spread to the surrounding areas, and the effect of the spreading would decrease with the increase of the distance. Britain (2002) points out that geographical space is not the only component of 12.

(25) the concept of space; instead, there were three types of space: (1) euclidean space, i.e. the objective, geometric, socially divorced space of mathematics and physics), (2) social space, i.e. the space shaped by social organization and human agency, by the human manipulation of the landspace, by the contextualization of face-to-face interaction, by the creation of a built environment, and by the relationship of these to the way the state spatially organizes and controls at a political level), and (3) perceived space (how civil society perceives it’s immediate and not so immediate environments-important given the way people’s environmental perceptions and. 政 治 大 of space do not exist independently. Therefore, when analyzing geographical variation, 立 attitudes construct and are constructed by everyday practice. Also, these various types. the social aspect of a linguistic variation should also be taken into consideration.. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.3.2 linguistic variation by formality. ‧. In stylistic variation, the influence of situational formality is examined. Labov. sit. y. Nat. (1972) proposes that speech styles can be categorized into careful speech and casual. io. er. speech. In careful speech, speakers usually use more standard forms and less nonstandard forms, while in casual speech, speaker usually use more nonstandard. al. n. v i n Chis forms and less standard forms. In study (1972), Labov designs different tools to he ngchi U. measure situational formality by using conversation, reading passages, word list, and a list of minimal pairs, with formality decreasing accordingly. Labov (1966), in his study of the stylistic and the social variation between [t] and [θ] as variants of /θ/ in New York City, finds that the use of the nonstandard form [t] decreases with the increase of stylistic formality. In another study of Labov’s (1966), the influences of formality and class on the use of postvocalic /r/ are verified. Bell (1984) says, “Variation on the style dimension within the speech of a single speaker derives from and echoes the variation which exists between speakers on the “social” dimension.” Following the same line, Chan (1984), in her study of Mandarin /ʐ/ in Taiwan by 13.

(26) Southern-Min speakers, finds that her subjects, in situation of higher formality (i.e. in reading passage, reading characters, and reading minimal pairs), use more standard form [ʐ] and less non-standard forms [l] and [z]; but they use more nonstandard forms and less standard form in casual conversation. Based on the findings of the studies given above, situational formality is included in this study. 2.2.3.3 linguistic variation by social space As mentioned above in section 2.2.3.1, social space is an important factor to linguistic variation. A good example for the study of linguistic variation in social. 政 治 大 /au/ and /aɪ/, in words such as mouse and mice, in Martha’s Vineyard. Results of data 立 context is Labov’s (1963) investigation of vowel centralization of two diphthongs,. ‧ 國. 學. analyses indicate that local people, tended to pronounce /a/ and /au/ as [əɪ] and [əu], in order to signal localism and loyalty to the island. In other words, this linguistic. ‧. variation of vowel centralization is initiated and spread on the island for social causes.. sit. y. Nat. Bailey (1993) uses random telephone survey to examine the diffusion of the. io. er. de-rounding of [ɔ] into [ɑ] in the center of Oklahoma City before 1945 and that after 1945. It is reported that the de-rounding process diffuses from big city to small city,. al. n. v i n C h Bailey concludesUthat different types of diffusion from large town to small town. Also, engchi may aim at different social meanings that linguistic forms carry. However, opposite to Bailey’s finding, Trudgill (1974) found contra-diffusion in his study in East Anglia’s research, with phonetic variation shifting from rural north Norfolk to Suffolk, the city center. These findings mentioned above that the path of linguistic variation and change travels in all directions. People have been socio-economically categorized into different social groups. In 19 century, Karl Marx proposed a theory of social class. Warner (1941), in his study of the New England City of Yankee City, suggests that social factors other than income and occupation (including educational background, family background, and 14.

(27) so on) should also be taken into consideration, and he (1960) built Evaluated Participation and the Index of Status Characteristics to measure social class. Labov (1972), in his study of the use of postvocalic /r/ in three department stores in New York City, reports that subjects of higher class and those who assign themselves to higher class use more postvocalic/r/, the prestigious form, than subjects of lower classes. Trudgill’s (1974) study of the Norwich England supports Labov’s point of view. In Trudgill’s study The pronunciation of –ing as [ɪŋ] or [ɪn] is found to be related to. 政 治 大 education and other social factors to categorize people into 5 social classes, namely, 立 the speakers’ social class. In his study, Trudgill makes use of occupation, income,. middle middle class, lower middle class, upper working, middle working, and lower. ‧ 國. 學. working class. The results of data analyses indicate that the lower classes tend to give. ‧. higher percentages of using [ɪn] than the higher classes.. sit. y. Nat. Labov (1966) proposes “change-from-above” and “change–from–below” to. io. er. explain linguistic variation, with change-from-above being lead by the prestigious class (not necessarily the highest one), while change-from-below being evoked and. al. n. v i n C hof postvocalic /r/ inUNew York City is an example lead by the working class. The use engchi of change-from-above; whereas the vowel centralization in Martha’s Vineyard is an. instance of change-from-below. In this thesis, the phonetic variation of Mandarin /ɕ/ between [ɕ] and [s] may probably be affected by social class, which is represented by informants’ educational background. Gender is one of the major factors that would determine people’s behaviors of various kinds. Cheshire (2002) defines the concept of sex as biologically determined, and the concept of gender as social-culturally identified. Labov (1990) lists three principles of gender differences: (1) Principle I: In stable sociolinguistic stratification, men use a higher frequency of nonstandard forms than women; (2) Principle Ia: In 15.

(28) change from above, women favor the incoming prestige forms more than men; and (3) Principle II: In change from below, women are most often the innovators.Levine and Crockett (1966), in their study of the postvocalic /r/ in southern states of United States, find that women, young people, the newer residents, and people of higher social status take the national r-norm as their speech model; while the linguistic behavior of males, older people, long term residents, and blue-collar respondents were found to comply to the southern prestige norm, namely, the r-less pronunciation of the coastal plain, Anshen (1969), in his cross gender comparison of the use of postvocalic /r/, finds a. 政 治 大 same line, Chan (1984) finds that female native speakers of Southern Min dialect use 立. similar results that women tend to use more prestigeous form than men. Following the. more prestigious forms of Mandarin /ʐ / than males do.. ‧ 國. 學. Nevertheless, there are counter examples. For instance, in Labov’s (1963) study. ‧. of vowel centralization in Martha’s Vineyard, young men, who sought to identify. y. Nat. themselves as native Vineyarders, reject the values and the speech style of the. er. io. sit. mainlanders, and use the local prestigious forms [əu] and [əɪ] more often than women. Also, Eckert (2012) points out that gender, like any other social factors, doesn’t. al. n. v i n work independently; instead, theCsignificance of gender h e n g c h i Uin linguistic variation has to do with how gender structures people’s lives at different places in society. In this. thesis, gender is examined individually as well as in combination with other social factors, for its influence on the phonetic realization of Mandarin /ɕ/. Linguistic variation in progress prescribes time. However, since it is hard to collect data diachronically, using data of apparent time becomes a way to solve the problem. Labov’s (1963) study of Martha’s Vineyard makes use of data of apparent time to observe the centralization of /aw/ and /ay/. With his subjects being divided into five different age groups, it is found that the odlest group shows the lowest rate of vowel centralization, and the group of 31 to 45 years old the highest. Out of 16.

(29) expectation, the youngest group does not score the lowest in this vowel centralization process. Opposite to this finding, Labov (1994) proposes that older people would slightly be affected by sound change; while the younger ones are more easily be affected. Cukor-Avila (2000) in his diachronic study of the use of zero third person singular, zero copula, habitual be+v+ing, and had+past used as a simple past in a rural Texas community of Springville where people used AAVE, four subjects of different ages were interviewed twice in an interval of seven year. The two older subjects show. 政 治 大 6-year-old subject’s use of zero copula decreases in the second interview. 立. no significant change, but the 9-year-old subject changes significantly, and the. Cukor-Avila’s research shows that the older subjects change slightly, while the. ‧ 國. 學. younger subjects show more obvious change. Chambers (2002), in his study of. ‧. speakers use of [w], not [hw], in words like which and whine, in central Canada, finds. sit. y. Nat. that the younger groups give higher percentages of using the new form [w], less by. io. er. older age group over 80 and the group between 70-79. Chamber’s findings support Cukor-Avila’s (2000) study. In this thesis, Hakka people of different generations will. al. n. v i n C h age has any impacts be examined in order to check whether to the phonetic realization engchi U of Mandarin /ɕ/.. 2.2.4 Language attitudes According to Bailey (1997), the course of sound change is influenced by the attitudes of the speech community toward that change. Before this statement is examined, it is important to know what it means by language attitude. Two theories about the nature of attitudes compete with each other–the mentalist’s view vs. the behaviorist view. First, as Fasold (1987) points out, most language attitude work is based on a mentalist view, taking attitude as a state of readiness (i.e. an interviewing variable between a stimulus and the response to that 17.

(30) stimulus); while the other view of attitude, the behaviorist view, claims that attitudes can be found in people’s responses to social situation. Moreover, social psychologists, taking the behaviorist definition of attitude, consider attitude as single units. Whereas, mentalists claim attitudes have three components; cognitive component, conative component, and affective component, with these three components referring to knowledge, action, and feeling, respectively. Language attitudes may extend to people’s attitudes toward a language, which is a reflection of people’s attitudes toward the speakers of that language. The study of. 政 治 大 language or a specific form in a language. For example, in Labov’s study (1966) on 立 language attitude can be applied to explain people’s motivations of using a specific. Martha’s Vineyard, the local residents’ use of the centralized vowels and their positive. ‧ 國. 學. attitude toward vowel centralization are to mark local identity. Hoover (1978) reports. ‧. that black Americans’ choice of Black English Vernacular (BEV) over standard. sit. y. Nat. English corresponds to their positive attitudes toward BEV, their mother tongue,. io. er. which is used to symbolize their ethnic identity. Based on this conception, in this thesis, the relationship between Hakka speakers’ attitudes toward the Hakka ethnic. al. n. v i n C h manifestation ofUMandarin /ɕ/ is examined. group and their use of [s] as a phonetic engchi. 18.

(31) Chapter Three Methodology. In order to identify the patterns, and the linguistic and nonlinguistic causes of this phonetic variation of Mandarin /ɕ/, both quantitative analysis and qualitative analysis were conducted.. 政 治 大 In quantitative analysis, the impact of both linguistic and non-linguistic factors 立. 3.1 Design of Quantitative Analysis. were examined. The former includes neighboring sounds within/beyond syllable. ‧ 國. 學. boundary, syllable structure, and lexical frequency. The latter includes situational. ‧. formality, geographical factor, and three social factors.. sit. y. Nat. 3.1.1 Linguistic factors. io. er. 3.1.1.1 neighboring sounds. It was hypothesized that neighboring sounds would affect the phonetic. al. n. v i n C h the sounds that precede realization of /ɕ/. In order to describe and those that follow /ɕ/, engchi U a conflation of those neighboring sounds of /ɕ/ is given below.. 19.

(32) ɯ u o y e I a n ŋ. i ia iɛ iou y yɛ. ## ɕ. (N). Within a syllable, Mandarin /ɕ/ is followed by a vowel. Since within a syllable,. 政 治 大 before the nucleus vowel, and 立since /y/, as a possible vowel following /ɕ/, is with. /ɕ/, except when followed by a monothong /i/, is always followed by an on-glide /i/. ‧ 國. 學. roundedness, which is phonosemantically impossible to induce [s] without causing meaning problems, the impacts of the following vowels were excluded from this study.. ‧. For these reasons, in this study, neighboring vowels refer to the vowels in the open. sit. y. Nat. syllable preceding /ɕ/, and what was examined is whether the advancement of the. n. al. er. io. preceding vowels is influential to the emergence of [s] through assimilation. 3.1.1.2 syllable structures. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Syllable structure was also predicted to be related with phonetic variation. In Mandarin Chinese, all of the syllable structures containing /ɕ/ can be reduced into one syllable frame: /ɕ/ + V(N). In other words, what was examined is whether the syllable final nasal is influential to the emergence of [s] in the initial position of the same syllable. Table 1 shows the syllable frames and the individual syllable structures examined in this study.. 20.

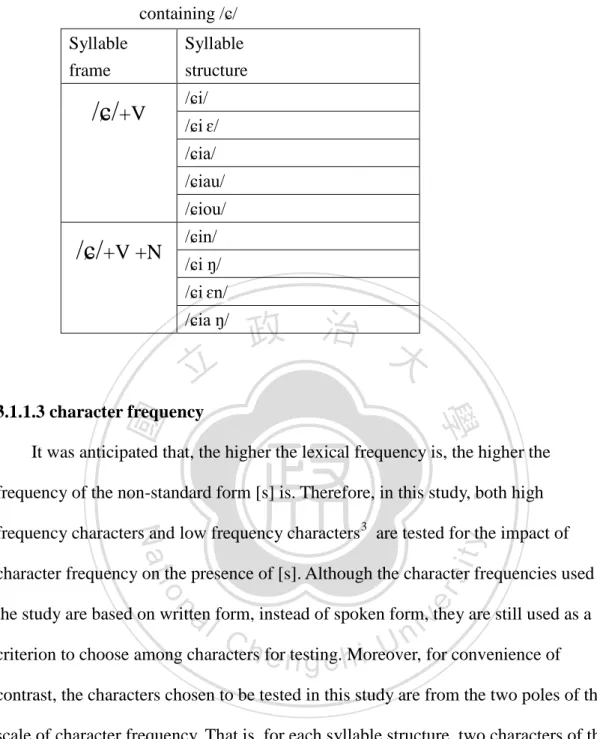

(33) Table 1. Syllable frames and syllable structures containing /ɕ/ Syllable frame. Syllable structure /ɕi/. /ɕ/+V. /ɕi ɛ/ /ɕia/ /ɕiau/ /ɕiou/ /ɕin/. /ɕ/+V +N. /ɕi ŋ/ /ɕi ɛn/ /ɕia ŋ/. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 3.1.1.3 character frequency. It was anticipated that, the higher the lexical frequency is, the higher the. ‧. frequency of the non-standard form [s] is. Therefore, in this study, both high. sit. y. Nat. frequency characters and low frequency characters 3 are tested for the impact of. n. al. er. io. character frequency on the presence of [s]. Although the character frequencies used in. i n U. v. the study are based on written form, instead of spoken form, they are still used as a. Ch. engchi. criterion to choose among characters for testing. Moreover, for convenience of contrast, the characters chosen to be tested in this study are from the two poles of the scale of character frequency. That is, for each syllable structure, two characters of the highest frequency and two characters of the lowest frequency were chosen and tested. These characters chosen were tested in all three speech styles (namely, conversation, passage reading, and characters reading). In total, there are 17 high frequency characters and 18 low frequency characters tested in this study. 4 Table 2 presents the 3. The frequencies of these target characters are derived from Academic Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese. 4 For syllable /ɕiou/, only one high frequency character is tested, because all of the other characters of this syllable structure, according to Academic Sinica Balanced Corpus of Modern Chinese, are of very 21.

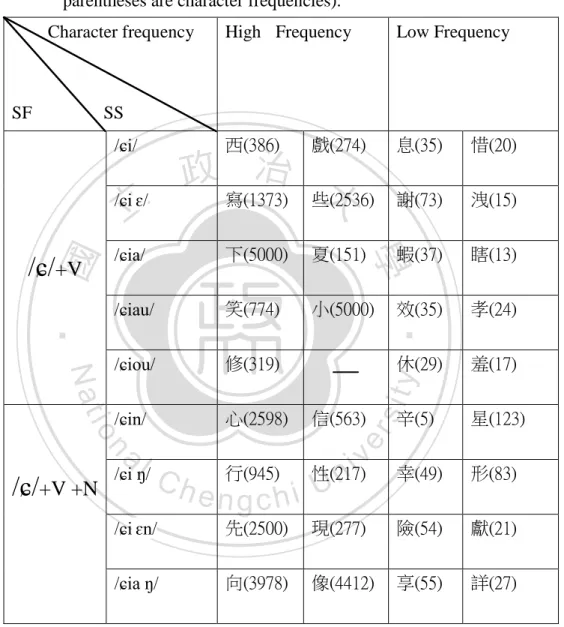

(34) related syllable structures, characters chosen for the nine syllable structures, and their character frequencies.. Table 2. Syllable structures and character frequency of / ɕ/ in the survey (SF=Syllable Frames, SS= Syllable Structures; numbers in parentheses are character frequencies). Character frequency. Low Frequency. 西(386). 息(35). 惜(20). 謝(73). 洩(15). SS /ɕi/. 政 治 大 寫(1373) 些(2536). /ɕi ɛ/. 立. 蝦(37). 瞎(13). /ɕiau/. 笑(774). 小(5000). 效(35). 孝(24). /ɕiou/. 修(319). ___. 休(29). 羞(17). /ɕin/. 心(2598). 信(563). 行(945). y 辛(5). 星(123). 性(217). 幸(49). 形(83). 先(2500). 現(277). 險(54). 獻(21). 向(3978). 像(4412). 享(55). 詳(27). n. al. /ɕ/+V +N. /ɕi ŋ/. Ch. /ɕi ɛn/ /ɕia ŋ/. sit. ‧ 國. 夏(151). io. 下(5000). ‧. Nat. /ɕia/. 學. /ɕ/+V. 戲(274). engchi. low frequency. 22. er. SF. High Frequency. i n U. v.

(35) 3.1.2 Non-linguistic factors Nonlinguistic factors are also expected to cast impacts on the phonetic variation of /ɕ/. In this study, non-linguistic factors include situational formality, geographical variable, age, gender, and education level. 3.1.2.1 situational formality Labov (1972), in his study of the stylistic variation and the social class variation of [t] and [ɵ] of /ɵ/ in New York City, discovered that speakers use more nonstandard variants in casual speech than in careful speech. In this thesis, three situational. 政 治 大 examined in order to investigate whether the emergence of [s] is stylistically evoked. 立 formalities (namely, conversation, reading passage, and reading characters) were. It was anticipated that [s]% would increase with the decrease of situational formality,. ‧ 國. 學. with [s]% being the highest in conversation (a style of lowest formality), lower in. ‧. reading passages (a style of intermediate formality), and the lowest in reading. sit. y. Nat. characters (a style of highest formality).. io. er. 3.1.2.2 nature of the geographical area. All of the subjects of this study are native speakers of Hakka, and they are. al. n. v i n equally distributed to two cities—Taoyuan City. The former is the C h City and Chungli engchi U. administration center of Taoyuan County and a city of commerce; the latter is a city of manufacturing industry. It was predicted that Chungli City, socioeconomically inferior to Taoyuan City, would yield higher percentages of [s]. 3.1.2.3 social factors In this study, the influences of age, gender, and education level are examined. Age is divided into two groups, the old and the young; gender is categorized into male and female; education level is divided into higher education level and lower education level. The influences of these social/geographical factors were examined individually first, and then in combination. Since the sample size is small (only 32 subjects), the 23.

(36) interactions among the non-linguistic factors were forced to limit to those by any two of the four external factors.. 3.2 The Tools Three tools were adopted for quantitative survey of the use of [s] in three styles. 3.2.1 Conversation Labov (1984) offers field methods for investigation of linguistic change and variation. For face-to-face conversation, Labov proposes the concept of module,. 政 治 大 face-to-face communication in a research as real as people in daily life. For this study, 立 which includes a group of questions focusing on a particular topic, to make the. five major topics are included in the conversations: (1) personality and appearance, (2). ‧ 國. 學. education, (3) food safety, (4) economy, and (5) life style. Under these 5 topics, there. ‧. are also some subtopics and subsubtopics to extend these topics into a natural. sit. y. Nat. conversation. In this way, if subjects can not be elicited by target words in questions,. io. er. subquestions are offered to provide more chances to secure enough quantity of subjects’ production of the target characters. All of the target characters were designed. al. n. v i n Cleast to appear in a conversation for at times. In total, twenty-three questions h ethree ngchi U were projected through the concept of module to link with each other.. Also, each conversation took about 50 minutes. During the conversations, in order to make them feel safe and comfortable to render natural data, the subjects were told that the purpose of the survey was not to check on their thinking or to probe for their privacy. All of the conversations were recorded with a digital recorder and transcribed for further analyses. For details of the conversation topics and sub-topics, see Appendix 1 (on p.95 of this thesis). In the appendix, those characters underlined are the target characters in this study. 24.

(37) 3.2.2 Reading passages In reading passages, subjects were asked to read 4 passages, which include popular issues in newspapers and magazines. 5 To cope with cross-style comparison, the topics for passage reading, like those for conversation, are also about (1) personality and filial obedience, (2) education, (3) food safety, and (4) fee of electricity in summer. In passage reading, each target character appears 3 times in the passages. In total, 105 instances of the target words were examined. Again, the data were recorded and transcribed for analyses. For contents of these passages, see. 政 治 大. Appendix 2 (on p.100 of this thesis). 3.2.3 Reading characters. 立. In reading characters, 35 target characters and 15 decoys were included in the. ‧ 國. 學. test. Subjects were asked to read each word one by one. For details of these characters,. 3.3 Design of Qualitative Analysis. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. targets, all of which were recorded and transcribed for analysis.. ‧. see Appendix 3 (on p.101 of this thesis). In the table, those characters in shade are the. n. v i n Cface-to-face After the quantitative tests, were conducted to elicit the h e n g cinterviews hi U. subjects’ language attitudes, since quantitative study can only describe the patterns of linguistic variation, and it is qualitative analysis that would offer explanations to the causes of the patterns. The qualitative design implemented in this study includes the following parts: the subjects’ stereotypical impression of Hakka people, subjects’ subjective judgments of the target phonetic variation, their opinions toward the necessity of the association between ethnic identity, their proficiency in Hakka dialect, and their frequency of using Hakka dialect, and so on. For details of the interview questions, see Appendix 5 5. These passages were adapted from the newspaper Apple Daily and the magazine Common Wealth. 25.

(38) (on p.103 of this thesis). Among the attitude tests, subjects’ attitudes toward Hakka dialect were expected to offer explanations to the distribution of the target phonetic variation. Ten pairs of attributes on value dimension were given on 7-point semantic differential scales were used for the subjects to rate their stereotypical impression on the Hakka dialect. For details of these attributes, see Appendix 4 (p.102 of this thesis).. 3.4 Measurements. 政 治 大 However, since the sample size is too small for statistic tests, only patterns and 立 In quantitative analysis, both percentages and frequencies are presented.. regularities were described for cross comparisons among internal factors and those. ‧ 國. 學. among external factors.. ‧. In qualitative analysis, statistical tests were also expected to be applied to. sit. y. Nat. examine the patterns found. In the analysis of the interviews, subjects’answers to the. io. al. n. discussed.. er. causes of their subjective judgments were categorized first, and then analyzed and. 3.5 Sampling. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 3.5.1 Source of subjects Milroy& Milroy (1978) used the way of “a friend of a friend” to enter a community. Labov (1963), in his work of vowel centralization on Martha’s Vineyard, chose locally born and raised adults and teenagers. In this study, subjects recruited are all locally born and raised either in Chungli City or in Taoyuan City. All of the subjects are either friends and relatives of this researcher’s or informants recruited by the way of “a friend of a friend,” starting from this researcher’s classmates in high school and in college, extending to their friends and relatives. 26.

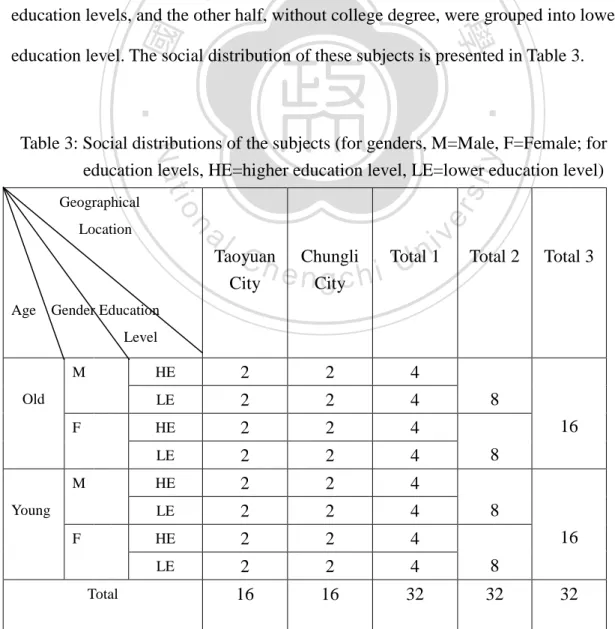

(39) or the qualitative interviews, only 29 of the thirty-two subjects for the quantitative tests were interviewed; the other three went abroad and could not be reached after the quantitative tests. 3.5.2 Social distribution of the subjects In this survey, 32 subjects were recruited equally distributed to 2 geographical areas (Chungli City vs. Taoyuan City), 2 genders ( male vs. female), 2 age groups (the old vs.the young), and 2 education levels (higher education level vs. lower education level).That is, half of the subjects ranging between 20 and 40 years old were grouped. 政 治 大 half of the subjects, who have received college degree, were classified as higher 立. into one age group, while the other half were between 45 to 60 years old. Moreover,. education levels, and the other half, without college degree, were grouped into lower. ‧ 國. 學. education level. The social distribution of these subjects is presented in Table 3.. ‧ sit. n. Location. Age. al. er. io. Geographical. y. Nat. Table 3: Social distributions of the subjects (for genders, M=Male, F=Female; for education levels, HE=higher education level, LE=lower education level). v. Taoyuan City. e nCity gchi. Chungli. i Totaln1 U. HE. 2. 2. 4. LE. 2. 2. 4. HE. 2. 2. 4. LE. 2. 2. 4. HE. 2. 2. 4. LE. 2. 2. 4. HE. 2. 2. 4. LE. 2. 2. 4. 8. 16. 16. 32. 32. Ch. Total 2. Total 3. Gender Education Level M. Old F. M Young F. Total. 27. 8 16 8 8 16 32.

(40) 3.6 The Procedure of Data Collection In this study, each subject was tested twice on separate days, with quantitative tests coming prior to qualitative. Also, stylistic tests start with a conversation of casual style, through a passage reading of intermediate formality, and to a character reading of high formality. Afterwards, 29 of the 32 subjects were interviewed for their language attitudes, starting with an evaluation of their stereotypical impression toward the Hakka dialect, moving on to their descriptions and explanations for their subjective judgments on the. 政 治 大 the association between Hakka ethnic identity, and their Hakka proficiency and their 立. Hakka people and the target phonetic variant, and their opinions about the necessity of. frequency of using Hakka.. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 28. i n U. v.

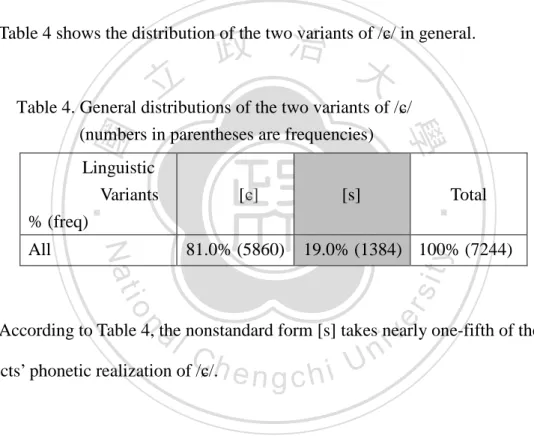

(41) Chapter Four Data Analysis. In this chapter, the phonetic variation of Mandarin /ɕ/ by linguistic and non-linguistic factors are described and analyzed.. 4.1 General distributions of the Two Variants of /ɕ/. 政 治 大. Table 4 shows the distribution of the two variants of /ɕ/ in general.. 立. [s]. 81.0% (5860). Total. 19.0% (1384) 100% (7244). n. al. er. io. sit. Nat. All. [ɕ]. y. Linguistic Variants % (freq). ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Table 4. General distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ (numbers in parentheses are frequencies). i n U. v. According to Table 4, the nonstandard form [s] takes nearly one-fifth of the. Ch. subjects’ phonetic realization of /ɕ/.. engchi. 4.1.1 Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by formality It was predicted that the use of the nonstandard form [s] would decrease with the increase of formality. Table 5 shows the distribution of [s] in the three different styles: conversation (CON, hereafter in this chapter), reading passages (RP, hereafter in this chapter), and reading characters (RC, hereafter in this chapter).. 29.

(42) Table 5. Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by formality (numbers in parentheses are frequencies) Variants of / ɕ/ Formality. [ɕ]. [s]. Total. Conversation. 73.0% (2020). 27.0% (744). 100% (2764). Reading passages. 84.9% (2850). 15.1% (510). 100% (3360). Reading characters. 88.6% (990). 11.4% (130). 100% (1120). According to Table 5, the subjects’ use of [s], as predicted, decreases as formality increase. To be specific, [s]% is the highest in CON (27.0%), which is of lowest. 政 治 大 nearly 12.0% and 16.0%, respectively. In other words, although the gap between the 立. formality; in contrast, when the formality increase s in RP and in RC, [s]% decreases. ‧ 國. 學. [s]% in CON is not particular large, it seems to be true that formality is as influential factor to subjects’ use of the non-standard form [s].. ‧ sit. y. Nat. 4.1.2 Distributions of the two variants of /ɕ/ by social/geographical factors. n. al. er. io. It was predicted that the subjects’ use of [s] is controlled by geographical. i n U. v. features of the place in which they live and their social characteristics.. Ch. engchi. 30.

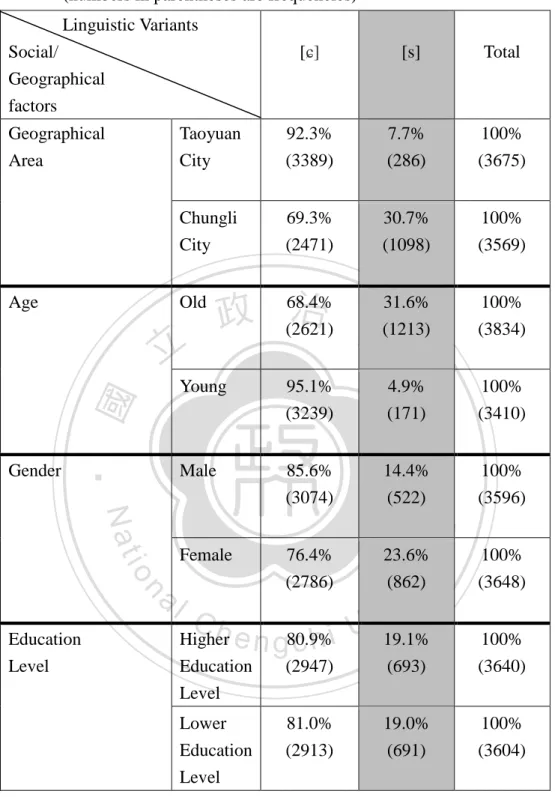

數據

![Table 15. Distributions of [s]% in Reading Characters by syllable structures](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7994768.159699/9.892.134.757.429.839/table-distributions-s-reading-characters-syllable-structures.webp)

+7

Outline

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Language attitudes

The Procedure of Data Collection

General distributions of [s]% by syllable structures

Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures, formality,

General distributions of [s]% by the advancement

Limitations

Topics for Conversation

Questions for Interview

相關文件

加強「漢語拼音」教學,使學生掌握

•三個月大的嬰兒在聆聽母語時,大腦激發 的區域和成人聆聽語言時被激發的區域一

• 「在香港定居的非華語學生與其他本地學 生,同樣是香港社會的下一代。……為促

個人、社會及人文教育 |英國語文教育| 藝術音樂教育 | STEM 教育 全球意識與文化敏感度 |體驗學習| 接觸大自然

學結合 目的 鼓勵說話 (目的語) 分析 詞彙

語音四要素 語音四要素與朗誦的關係 音高 語音的高低抑揚顯示語言的節奏感 音強

潘銘基, 1999 年畢業於香港中文大學中國語言 及文學系,繼而於原校進修,先後獲得哲學碩士

• (語文)術語學習 無助學生掌握有關概念,如 果教師只灌輸術語的定義,例如何謂「動

![Table 7. Distributions of [s]% by social/geographical factors and formality (numbers in parentheses are frequencies)](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7994768.159699/46.892.133.853.162.815/table-distributions-geographical-factors-formality-numbers-parentheses-frequencies.webp)

![Table 8. General distributions of [s]% by syllable structures (numbers in parentheses are frequencies)](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7994768.159699/48.892.177.718.188.305/table-general-distributions-syllable-structures-numbers-parentheses-frequencies.webp)

![Table 10. Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures and](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7994768.159699/50.892.187.711.175.994/table-distributions-s-syllable-structures.webp)

![Table 11. Distributions of [s]% by syllable structures, formality, and](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libinfo/7994768.159699/52.892.130.822.166.847/table-distributions-s-syllable-structures-formality.webp)